Abstract

Posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, are a powerful means by which the activity and function of nuclear receptors such as LXRα can be altered. However, despite the established importance of nuclear receptors in maintaining metabolic homeostasis, our understanding of how phosphorylation affects metabolic diseases is limited. The physiological consequences of LXRα phosphorylation have, until recently, been studied only in vitro or nonspecifically in animal models by pharmacologically or genetically altering the enzymes enhancing or inhibiting these modifications. Here we review recent reports on the physiological consequences of modifying LXRα phosphorylation at serine 196 (S196) in cardiometabolic disease, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, atherosclerosis, and obesity. A unifying theme from these studies is that LXRα S196 phosphorylation rewires the LXR-modulated transcriptome, which in turn alters physiological response to environmental signals, and that this is largely distinct from the LXR-ligand–dependent action.

Keywords: liver X receptors, phosphorylation, atherosclerosis, obesity, NAFLD, transcription, nuclear receptors

Liver X receptors (LXRs) are ligand-activated transcription factors that control lipid and glucose homeostasis, as well as inflammation (1, 2). LXRs consist of 2 subtypes, LXRα and LXRβ (NR1H3 and NR1H2, respectively), which exhibit 75% sequence homology (3). LXRα is expressed in tissues involved in lipid metabolism, such as adipose tissue and liver, as well as in bone marrow and immune cells, whereas LXRβ is ubiquitously expressed (4). Like other nuclear receptors, LXR is organized with an N-terminal activation function, a central DNA-binding domain followed by a flexible hinge region, and a C-terminal the ligand-binding domain (Fig. 1A). LXRs forms obligatory heterodimers with 9-cis retinoid X receptor (RXR) and are activated by desmosterol and oxysterols (2, 5), which are oxidized cholesterol derivatives. LXR can also homodimerize (6); however, the biological significance of this interaction has not been demonstrated. In the absence of a ligand, the LXR/RXR heterodimer occupies LXR response elements (LXREs) on the regulatory regions of target genes (7). Unliganded LXR/RXR interacts with co-repressors, such as the nuclear receptor co-repressor (NCoR) and silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor, thereby silencing gene expression (8). This is also known as ligand-independent active repression. Once the ligand binds to nuclear receptors, their ligand-binding domain undergoes a structural shift to a more stable position, which inhibits co-repressor interaction and creates a high-affinity site for coactivator proteins (9). These coactivator complexes are responsible for the modification of chromatin structure, thereby facilitating the assembly of the general transcriptional machinery to the gene promoter and inducing ligand-dependent transactivation of gene expression (10). LXRs can also repress gene expression through a mechanism known as transrepression (11, 12), by which LXRs antagonize the activity of other signal-dependent transcription factors, such as the nuclear factor-κβ and activator protein 1 (13, 14). It appears this is partly the mechanism through which LXRs exert their anti-inflammatory functions (15, 16). LXRs must be present in the nucleus to regulate target gene transcription, and the LXRα subtype has shown nuclear localization both in the absence and presence of its ligands (17, 18).

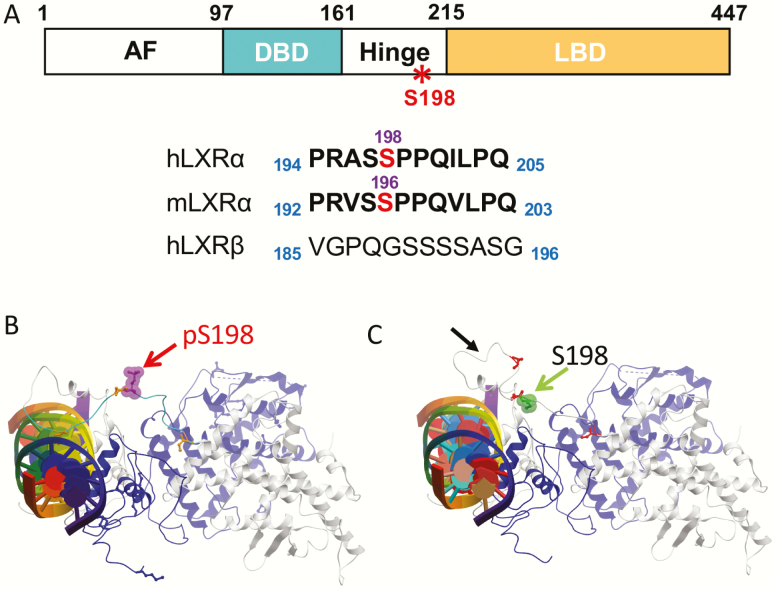

Figure 1.

Liver X receptor (LXR)α serine 196 (S196) phosphorylation of the hinge region. A, Schematic of human LXRα showing the N-terminal activation function (AF), DNA-binding domain (DBD), the hinge region, the ligand-binding domain (LBD), and conservation of the LXRα phosphorylation site in mouse on the S196. Phosphorylated serine residues are in red. This site is not conserved in LXRβ. B and C, Molecular modeling of LXRα S198 phosphorylation on the DNA-bound LXRα–retinoid X receptor (RXR)α heterodimer reveals changes in LXRα S198 residue orientation on phosphorylation: conformations of the human LXRα-RXRα heterodimer bound to DNA (multicolored cylinder with central plates) B, in the S198 phosphorylated form (red arrow) and C, in the S198 nonphosphorylated form (green arrow). Residues 181 to 195 loop orientation in the LXRα S198 nonphosphorylated state is altered in the phosphorylated state (C, black arrow). RXRα is shown in blue, and LXRα is depicted in gray. Adapted from (27) with permission.

Most proteins are subjected to posttranslational modifications, which are covalent modifications catalyzed by specific enzymes that result in changes in protein function (19, 20). Posttranslational modifications of nuclear receptors, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, sumoylation, methylation, and O-GlcNAcylation, play important regulatory roles and allow rapid and reversible molecular changes in the nuclear receptor response (21). Phosphorylation (22-24), O-GlcNAcylation (25), and acetylation (26) of LXRα have been shown to influence LXRα-mediated transcriptional activation of target genes through changes in LXRα stability, transcriptional activity (either increasing or decreasing LXRα transcriptional potential), and/or recruitment of transcription factors at specific LXR target genes.

We have demonstrated that altering LXRα phosphorylation modifies its target gene repertoire in vitro in LXRα-overexpressing macrophage-like cell lines (22, 27), and more recently in vivo in the context of cardiometabolic disease models of atherosclerosis progression (28), atherosclerosis regression, and diabetes (29), obesity (30) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (31). In this review, we discuss these recent findings and the potential of targeting LXRα phosphorylation for chronic inflammatory diseases.

Liver X Receptor α Phosphorylation at Serine 198 and Its Kinases

LXRα is phosphorylated at serine 198 (S198) in human LXRα, and at the cognate serine 196 (S196) site in the mouse (22-24). Phosphorylation of this site is observed in mouse and human macrophages in vitro and in atherosclerotic plaque macrophages in apolipoprotein E knockout (Apoe KO) mice (22, 27), as well as in the liver (24, 31). This site is located in the hinge region of LXRα, and is conserved between humans, rats, and mice but absent in LXRβ (Fig. 1A). Phosphorylation at this site is increased by both endogenous and synthetic LXR ligands (24[S],25-epoxycholesterol and T0901317 or GW3965, respectively), and has been reported to be a substrate of casein kinase 2 (CK2) (22) and protein kinase A (24). Phosphorylation at S198 also affects LXRα transcriptional activity in a gene-selective manner. Molecular modeling of the DNA-bound LXRα-RXRα heterodimer (32) reveals alterations in the orientation of the LXRα S198 residue on its phosphorylation. Phosphorylated S198 is exposed on the surface of the complex, consistent with a site for protein interactions (Fig. 1B), whereas the unphosphorylated S198 is buried. However, a segment containing the unphosphorylated S198 adopts a short alpha helical stretch, suggesting an additional surface for protein interaction in this S198 nonphosphorylated state (27) (Fig. 1C). This is consistent with the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated LXRα imparting distinct structural characteristics to the hinge domain to influence cofactor recruitment, and modulating LXRα activity in a gene-specific manner. Given the structural impact and functions effects of LXRα phosphorylation at this site in cell-based models, we examined the relevance of LXRα phosphorylation in mouse models of cardiometabolic disease, which is the focus of this review.

Liver X Receptor α S196 Phosphorylation–Deficient Knockin Mice

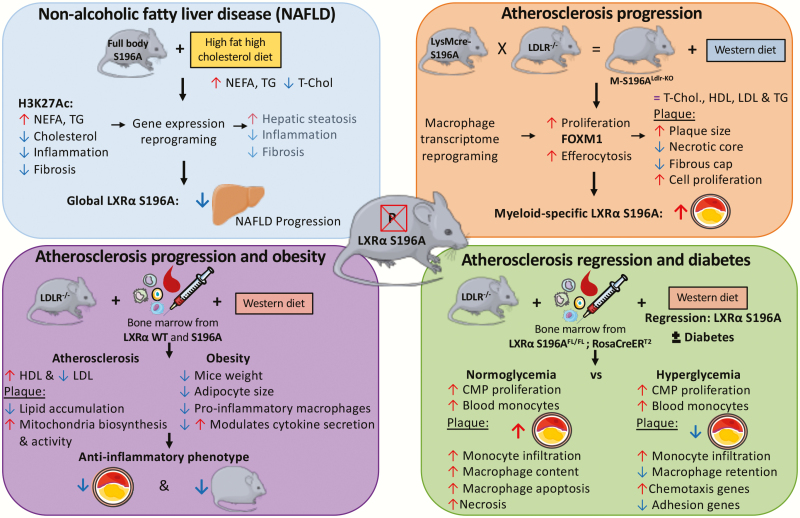

To determine the effect of mouse LXRα S196 phosphorylation (pS196) in vivo, we developed a global LXRα S196A knockin mouse carrying a serine-to-alanine mutation (S196A) introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. This mutation prevents phosphorylation at this site but does not significantly affect the level of LXRα expression. The LXRα S196A mice do not present any apparent morphological phenotype, have similar developmental growth compared to matched wild-type (WT) mice, and exhibit equivalent metabolic parameters (31). These mice have been used to determine the effect of LXRα phosphorylation in vivo on various diseases, such as NAFLD (31), atherosclerosis (28), diabetes (29), and obesity (30). Their phenotypes and mechanisms are discussed later and summarized graphically in Fig. 2 and the models, sex of the animals, diets used, and phenotypes are detailed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Liver X receptor (LXR)α serine-to-alanine mutation at Ser196 (S196A) mouse models in cardiometabolic diseases. Top, left, The full body knock-in of LXRα S196A showed reduced progression from steatosis to steatohepatitis in a model of diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (31). Top, right, A myeloid specific knock-in of LXRα S196A in an atherosclerotic background demonstrated that LXRα S196A increased atherosclerosis via enhanced macrophage proliferation. Bottom, left, and bottom, right, bone marrow transplant models in which all hematopoietic cells express LXRα S196A revealed that LXRα S196A decreased atherosclerosis progression and obesity (30) and reduced atherosclerosis during regression in a diabetic context (29).

Table 1.

Models used in assessing liver X receptor α S196 phosphorylation in cardiometabolic diseases

| Disease | Model | CRE | S196A expression | Genetic background | Diet | Sex | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerosis | LXRαS196AFL/FL | LYSM-CRE | Monocyte/Macrophage | C57Bl6; Ldlr–/– | WDa | Male | Increased atherosclerosis and macrophages proliferation | Gage et al (28) |

| NAFLD | LXRαS196AFL/FL | PGK1-CRE | Whole body | C57Bl6 | HFHCb | Female | Retards NAFLD progression | Becares et al, (31) |

| Atherosclerosis and diabetes | LXRαS196AFL/FL | ROSA-CRE-ERT2: BMT | All hematopoietic cells | C57Bl6; Ldlr–/– | WDc | Male | Decreased macrophage adhesion in diabetic plaques | Shrestha et al, (29) |

| Atherosclerosis and obesity | LXRαS196AFL/FL | ROSA-CRE-ERT2: BMT | All hematopoietic cells | C57Bl6; Ldlr–/– | WDc | Male | Decreased atherosclerosis and obesity | Voisin et al, (30) |

Abbreviations: BMT, bone marrow transplant; FL, floxed allele; HFHC, high fat high cholesterol; Ldlr, low-density lipoprotein receptor; LXR, liver X receptor; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; S196A, serine-to-alanine mutation at Ser196; WD, Western diet.

aWD = 20% (wt/wt) fat, 0.15% cholesterol.

bHFHC = 17.2% cocoa butter, 2.8% soybean oil, 1.25% cholesterol, 0.5% sodium cholate.

cWD = 21% (wt/wt) fat, 0.3% cholesterol.

Liver X Receptor α (LXRα) Phosphorylation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)—LXRα Serine-to-Alanine Mutation at Ser196 Retards NAFLD Progression

NAFLD is a progressive liver disease that ranges from simple fatty liver (steatosis) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (33). NAFLD is the major cause of chronic liver disease in the Western world, and is predicted to become the main cause for liver transplantation by 2030 (34). NAFLD may progress from benign steatosis to inflammatory and fibrotic steatohepatitis. LXRs contribute to this pathology by promoting fatty acid and triglyceride accumulation (35). Although deletion of LXRs in mouse models have shed light onto the LXR-mediated pathways controlling steatohepatitis (36, 37), the impact of LXRα phosphorylation on NAFLD progression remained unclear, and we sought to address this gap.

To this end, Becares et al (31) used a global knockin mouse carrying an LXRα homozygous serine-to-alanine mutation at Ser196 (S196A) that impairs LXRα phosphorylation without affecting overall hepatic LXRα levels (LXRα S196A mouse). Because cholesterol induces LXRα phosphorylation (22), it was hypothesized that LXRα S196A mice may respond differently to a high-fat, high-cholesterol (HFHC) diet when compared to chow.

Phenotype

LXRα S196A mice fed an HFHC diet showed higher levels of hepatic nonesterified fatty acids and triglycerides compared to WT mice and exhibited enhanced hepatic steatosis. Livers of the LXRα S196A mice featured increased numbers of larger lipid droplets, associated with enhanced expression of lipid droplet genes. Because plasma nonesterified fatty acids, triglycerides, and insulin levels did not differ between genotypes, the increased hepatic fat accumulation in S196A mice was likely a result of enhanced de novo lipogenesis. In fact, S196A livers showed an increase in the total amount of saturated as well as unsaturated fatty acids, specifically ω9 and certain ω6 fatty-acid species. Thus, LXRα S196A expressed globally induces hepatic steatosis and alters fatty-acid profiles in response to a HFHC diet.

Despite the increased steatosis, HFHC-fed LXRα S196A mice displayed less liver inflammation and collagen deposition than their WT counterparts. This was associated with reduced expression of proinflammatory and profibrotic mediators. Expression of factors involved in the activation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress were reduced in LXRα S196A mice, suggesting these animals are protected from lipotoxicity through a reduction in ER stress. In addition, HFHC-fed LXRα S196A mice were protected from plasma and hepatic cholesterol accumulation. This was accompanied by a 20% reduction in liver weight in LXRα S196A compared to controls and a decrease in the expression of the cholesterol efflux transporter ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 1. The HFHC-fed LXRα S196A mice also showed a unique induction in the expression of the cholesterol transporter adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette subfamily G member 5. Thus, reduced cholesterol accumulation in S196A mice is likely due to increased hepatobiliary secretion of cholesterol.

Mechanism

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on livers from LXRα S196A and WT mice fed an HFHC diet to gain insight into the mechanism of steatosis managed by LXRα phosphorylation. This revealed increased expression of a subset of the hepatic enzymes involved in fatty-acid elongation and fatty-acid oxidation. These changes likely contribute to the distinct hepatic fatty-acid profile of S196A mice.

LXRα S196A mice also showed a decrease in the levels of wound healing and fibrotic mediators, including collagen genes and enzymes responsible for collagen stabilization. Moreover, expression of a subset of genes involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and tissue regeneration that distinguish between low-risk and high-risk NAFLD among presymptomatic patients (38) were remarkably different between WT and S196A mice. Thus, LXRα phosphorylation could alter preclinical NAFLD progression by regulating tissue regenerative and remodeling pathways.

Variations in the hepatic transcriptome observed in the liver of LXRα S196A mice compared to WT coincided with changes in chromatin modifications: differences in H3K27 acetylation, which mark active genes, between LXRα WT and S196A mice strongly overlapped with changes in gene expression. For example, expression of the carboxylase 1F (Ces1f) gene was strongly induced in livers from LXRα S196A on an HFHC diet while showing a significant increase in H3K27Ac compared to WT. In silico analysis of the Ces1f gene for putative LXR binding sites revealed a degenerate direct repeat 4 sequence resembling the LXRE consensus binding site (7). In livers from the LXRα S196A HFHC-fed mice, this site was preferentially bound by LXR compared to WT, and was associated with increased RNA polymerase II (Pol II) and phosho-Ser2 Pol II occupancy, indicative of enhanced transcriptional initiation and elongation. This suggests that impaired LXRα pS196 allows for the transcriptional activation of new target genes containing noncanonical direct repeat 4 sequences.

We have previously reported using a macrophage cell line that on LXR ligand activation, phosphorylation affected the transcriptional activity of LXRα by modulating the binding of the NCoR corepressor to genes controlled by LXRα phosphorylation (22). However, differences in NCoR occupancy in the livers of mice exposed to the HFHC diet were not detected, suggesting responses to cholesterol in vivo involve other transcriptional regulatory factors whose interaction with LXRα is sensitive to phosphorylation. One such factor is the transducin β-like 1 X-linked receptor 1 (TBLR1), which participates in nuclear receptor cofactor exchange (39) and modulates LXR target gene expression in hepatic cells (40). TBLR1 was found to preferentially bind to LXRα S196A and occupy the Ces1f LXRE in livers from LXRα S196A as compared to WT HFHC-fed mice. Ces1f is a carboxylesterase that regulates very low-density lipoprotein (LDL) lipid packaging and assembly in the hepatocytes (41), with enhanced expression expected to result in increased hepatic lipid clearance. This suggests changes in LXRα phosphorylation at Ser196 in the context of a cholesterol-rich diet affect its interactions with regulatory factors such as TBLR1 to drive new sets of target genes that influence diet-induced responses in liver.

Liver X Receptor α Phosphorylation in Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a metabolic and inflammatory disease that begins when cholesterol-rich LDL and other apolipoprotein B–containing lipoproteins in the circulation are deposited in the subendothelial space of large arteries, where they and their modified forms promote inflammatory responses (42). In macrophages, LXRα signaling is critical for the homeostatic response to cellular lipid loading (43). Macrophage uptake of normal and oxidized LDL leads to increased cellular concentrations of cholesterol and oxysterols. Activation of LXRs by oxysterols induces the expression of genes involved in cellular cholesterol trafficking and efflux. However, in the face of persistent high cholesterol (hyperlipidemia), the LXR-mediated cholesterol homeostatic mechanism in macrophages is overwhelmed. This results in their becoming foam cells retained in the subendothelial space and the growth of an atherosclerotic plaque (42). In addition, plaque macrophage content reflects additional parameters including monocyte recruitment, macrophage proliferation and apoptosis, and efferocytosis, the process by which dead cells are removed by phagocytosis. We initially reported an increase in LXRα pS196 in plaque macrophages under inflammatory conditions associated with atherosclerosis progression, and a decrease in LXRα pS196 during the resolution of inflammation in regressing plaques. We also demonstrated in vitro that LXRα pS196 selectively regulates a subset of LXRα target genes in macrophages, including genes with anti-inflammatory and atheroprotective functions (22, 27). However, the specific contribution of LXRα phosphorylation in macrophages and immune cells to atherosclerosis development remained unknown.

Altering liver X receptor α phosphorylation in macrophages during atherosclerosis progression: impact on forkhead box protein M1 expression and macrophage proliferation

Phenotype.

To address the impact of LXRα phosphorylation in macrophages in atherosclerosis, Gage et al (28) generated a mouse model expressing LXRα S196A specifically in myeloid cells on the LDL receptor (LDLR)-deficient (Ldlr-KO) atherosclerotic-prone background (M-S196ALdlr-KO). This was accomplished using a conditional LXRα S196A mouse whereby LysM-Cre–mediated recombination of lox sites results in the replacement of the WT LXRα with the nonphosphorylatable S196A allele. The LysM-Cre promotes significant recombination in the monocyte/macrophage lineage, as well as promoting recombination in neutrophils (44).

M-S196ALdlr-KO mice fed a Western diet for 12 weeks developed accelerated plaque progression compared to WTLdlr-KO controls, shown through increased lipid content measured by en face examination of aortas and plaque coverage in aortic roots. Despite no change in the metabolic characteristics such as systemic glucose or lipid homeostasis, atherosclerotic plaques were larger in M-S196ALdlr-KO compared to control mice. This reflected increased proliferation of cells within the plaque (likely macrophages). Smaller necrotic cores and reduced fibrous caps of the M-S196ALdlr-KO plaques were also observed.

Mechanism.

To determine the mechanism of increased atherosclerosis in M-S196ALdlr-KOmice, the transcriptomic profiles of bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from the Western diet-fed mice were compared. This revealed significant genome-wide transcriptional changes and an enrichment in G2/M checkpoint and E2F targets, indicating cell cycle and cell proliferation pathways were induced in macrophages expressing LXRα S196A. This included a 3-fold increase in the proto-oncogene forkhead box protein M1 (FoxM1) and several of its target genes from Western diet-fed LXRα S196A compared to WT LXRα BMDMs. Macrophages expressing the LXRα S196A also showed increased proliferation. Interrogation of chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data and in silico analysis identified specific LXRα occupancy at the FoxM1 gene in macrophages. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of FoxM1 using the specific inhibitor FDI-6 (45) reduced the LXRα S196A macrophage proliferation and FoxM1 target gene expression, confirming that FoxM1 upregulation mediates the increased macrophage proliferation observed in M-S196ALdlr-KO mice. Interrogation of the LXRα S196A-regulated transcriptome also revealed selective expression of several prophagocytic and antiphagocytic molecules predicted to increase efferocytosis, which may contribute to the decreased necrotic core size observed.

To further understand the magnitude of the transcriptional changes imposed by the LXRα phosphorylation disruption, response to an LXR ligand GW3965 was explored through RNA-seq analysis on Western diet–exposed M-196ALdlr-KO and WTLdlr-KO BMDM. GW ligand activation promoted substantial changes in macrophage gene expression that was different and of a different magnitude in cells expressing the LXRα S196A mutant compared with WT macrophages, highlighting the significance of LXRα pS196 in rewiring the LXRα transcriptome.

Inhibiting liver X receptor α phosphorylation in bone marrow cells during atherosclerosis progression promotes an antiatherogenic phenotype

In addition to macrophages, other immune cells accumulate in the arterial wall and contribute to atherosclerosis (46-48). In a complementary approach to the macrophage specific knockin described earlier, Voisin and colleagues (30) studied the requirement of LXRα phosphorylation on the entire cadre of immune cells expressing LXRα S196A compared to WT using a bone marrow transplantation model into the atherosclerotic-prone Ldlr-KO fed a Western diet to promote plaque formation. This strategy can provide evidence for communication between immune cells types in atherosclerosis that respond to LXRα phosphorylation.

Phenotype.

In contrast to myeloid-specific LXR S196A, plaques from LXRα S196A bone marrow–transplant mice showed reduced lipid accumulation in the plaques and reduced macrophage proliferation. LXRα S196A decreased the recruitment of inflammation-prone Ly6Chigh monocytes, which was opposed by a decrease in macrophage apoptosis. Consequently, we observed a small reduction in plaque size and macrophage (CD68+ cells) accumulation. In this model, unlike the myeloid-specific knockin, lipoprotein profiles were affected with an increase in atheroprotective high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and a decrease in atherogenic LDL-C in LXRα S196A compared to WT. This increase in HDL-C may occur through recruitment of LXRα S196A expressing resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) to the liver in the context of bone marrow transplantation after whole-body irradiation to influence liver cells to either increase HDL-C particle secretion or decrease HDL-C uptake (49, 50).

Mechanism.

To characterize the mechanisms governing macrophage phenotype in atherosclerotic plaques when LXRα phosphorylation at S196 is inhibited in all bone marrow–derived cells, we examined by RNA-seq the gene expression profiles of CD68+ plaque macrophages collected by laser-capture microdissection from LXRα S196A and LXRα WT mice (51). Genes repressed by LXRα S196A aligned to proinflammatory pathways, whereas genes induced by LXRα S196A were associated with mitochondrial function and oxidative phosphorylation pathways but not fatty-acid oxidation. This indicates that mitochondrial activity and energy metabolism are induced in LXRα S196A CD68+ cells relative to WT. These are characteristics of metabolic pathways upregulated in anti-inflammatory macrophages. In parallel, we found that LXRα S196A M1 BMDMs had increased basal respiration, ATP production, fatty-acid metabolism, and mitochondrial abundance. Because the metabolic dependence of macrophages on oxidative phosphorylation is a hallmark of the anti-inflammatory response by M2 macrophages (52), our findings indicate that inhibiting LXRα phosphorylation at S196 in CD68+ plaque macrophages promotes the acquisition of an anti-inflammatory metabolic phenotype.

The difference in phenotype between the myeloid-specific expression of S196A described earlier vs the bone marrow–transplant model, in which the entire complement of hematopoietic cells express LXRα S196A, suggests that LXRα S196A expression within additional bone marrow–derived cells restrains macrophage proliferation in the plaque to deter atherosclerosis. Recent advances in single-cell RNA-seq revealed different leukocyte clusters, including T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, and natural killer cells, are present in the plaques of Ldlr-KO mice fed a Western diet (53). Elucidating which cell subset influences macrophage proliferation within the plaques of LXRα S196A mice remains an interesting and open question.

Liver X Receptor α Phosphorylation in Cardiometabolic Diseases

Disrupting liver X receptor α phosphorylation in bone marrow during atherosclerosis progression protects against diet-induced obesity

Obesity shares pathological features with atherosclerosis, including chronic inflammation mediated both by innate and adaptive immune cells that accumulate in the visceral adipose tissue and contribute to adipocyte dysfunction (54). Given the pivotal role of LXRα in cholesterol metabolism and inflammation and the influence of LXRα pS196 on gene expression, strategies that reduce LXRα pS196 could help diminish obesity. To determine the effect of LXRα pS196 on diet-induced obesity, we took advantage of the bone marrow–transplant model of LXRα S196A in Ldlr-KO background (30).

Phenotype.

Ldlr-KO mice reconstituted with LXRα WT or S196A bone marrow fed a Western diet become obese. Interestingly, LXRα S196A mice gained less weight (15% less than WT mice) after 16 weeks of the Western diet. Despite equivalent food intake, bone mineral density, and lean body mass, LXRα S196A mice showed reduced fat mass, in particular perigonadal white adipose tissue mass (pWAT), compared to LXRα WT mice. Consistent with the reduced lipid accumulation in perigonadal adipose tissue, we also observed a decrease in adipocyte size when LXRα S196 phosphorylation was inhibited.

Mechanism.

Associated with the reduction of adipose tissue, flow cytometry of the perigonadal adipose tissue revealed that LXRα S196A altered a unique type of immune cell population. Total adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) and recruited proinflammatory triple-positive F4/80+CD11b+CD11c+ (FBC) macrophages (M1-like macrophages) were reduced, although the number of resident anti-inflammatory double-positive F4/80+CD11b+ CD11c– (FB) macrophages (M2-like macrophages) did not change. This resulted in a higher ratio of inflammation-resolving FB to inflammation-promoting FBC macrophages in LXRα S196A adipose tissue compared to LXRα WT (55). Dendritic cell and T-cell numbers were not affected by LXRα S196A. RNA-seq analysis of ATMs revealed a large change in the LXRα S196A transcriptomes between ATM subtypes consistent with a less-inflammatory phenotype, suggestive of reduced inflammatory-mediated signaling to adipocytes.

Thus, expression of LXRα S196A in the bone marrow significantly decreased mouse weight, total fat, pWAT, and adipocyte size in pWAT compared to WT. This phenotype was not reported in myeloid-specific S196A expressing mice in the Ldlr-KO background, suggesting that other bone marrow–derived cells in combination with macrophages are promoting this phenotype (30).

Disrupting liver X receptor α phosphorylation alters atherosclerosis regression associated with diabetes

Diabetic patients have earlier onset and more extensive atherosclerosis than nondiabetic patients (56, 57). Clinical data show that diabetes significantly hampers the regression of human atherosclerosis, even when lipid levels are lowered (58). This effect has been recapitulated in a mouse model of atherosclerosis in which the favorable effects of lowering lipid levels on plaque development are impaired in diabetic mice (59). Plaque regression—the ability to resolve inflammation on lipid lowering—is also significantly impaired in diabetic mice compared to nondiabetic mice, even when LDL-C is similarly reduced in both (59). We have demonstrated that a chronically high level of glucose alters LXR-dependent gene activation in BMDM, suggesting that LXR function is dysregulated by hyperglycemia in diabetes (60). Given that phosphorylation of LXRα at S196 was increased by diabetes-relevant high glucose levels in a macrophage cell line and also modulated LXRα-gene expression, we examined whether LXRα function in atherosclerosis regression is impaired in diabetic mice as a function of pS196. To determine whether LXRα phosphorylation affected macrophage function during atherosclerosis regression in diabetes, we used an inducible LXRα pS196A-deficient knockin mouse so plaques could develop normally under LXRα WT expression and then be switched to LXRα S196A to isolate the effect of LXR phosphorylation on regression. Mice homozygous for LXRα S196A floxed allele (S196AFL/FL) with or without a tamoxifen-inducible CRE recombinase (RosaCreERT2;Cre+ or Cre–) were used as donors for bone marrow transplantation into recipient Reversa mice (Ldlr−/−; ApoB100/100; microsomal triglyceride transfer protein [Mttpfl/fl]; Mx1-Cre+/+) (61). This is an Ldlr-KO model in which the hyperlipidemia can be reversed after conditional inactivation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. The mice were fed a Western diet for 16 weeks to allow plaques to develop. Tamoxifen was administered at week 14.5 to all groups. This induced recombination of LoxP sites in the Cre-expressing mice, resulting in the replacement of LXRα WT with the LXRα S196A allele after the development of atherosclerosis. The regression/diabetic mice were administered an intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin for 5 days to induce hyperglycemia (29).

Phenotype.

Expression of LXRα S196A in hematopoietic cells had differential effects on atherosclerosis regression in normoglycemic vs hyperglycemic conditions. Under normoglycemia, LXRα S196A expression increased macrophage accumulation, macrophage apoptosis, and plaque necrotic area. In diabetes, LXRα S196A reduced macrophage retention in the plaque, which would be predicted to be antiatherogenic and enhance plaque regression. However, this favorable effect on regression was negated by increased monocyte infiltration in the plaque, attributed to increased leukocytosis in LXRα S196A mice.

Mechanism.

The increase in macrophage plaque accumulation under normoglycemia observed in LXRα S196A mice is due to an increase in the number of circulating white blood cells, especially monocytes. In fact, elevated white blood cell counts have been linked to an increased incidence of coronary heart disease in humans (62). Monocytosis occurs in hypercholesterolemic animal models as a result of Western diet feeding, which promotes accumulation of macrophages in the plaque (63). Plaques from LXRα S196A mice also showed an increased necrotic area and higher numbers of apoptotic macrophages compared to WT. This is likely the result of a defect in efferocytosis because plaque macrophages expressing LXRα S196A showed reduced expression of the efferocytosis promoting factor Mertk, a known LXR target gene (64).

Although LXRα S196A reduced macrophage retention in plaques in diabetes, this favorable effect on regression is masked by increased monocyte infiltration in the plaque attributed to increased leukocyte production in LXRα S196A mice. Thus, in the absence of leukocytosis, the phosphorylation-deficient LXRα S196 has atheroprotective effects in diabetes by reducing the retention and accumulation of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaque (29).

Liver X Receptor α Serine 196 Phosphorylation as a Potential Drug Target

LXRα represents a promising target for the treatment of diseases involving dysregulation of metabolism and inflammation given that its activity can be controlled both by small molecule ligands and phosphorylation. This includes atherosclerosis (15), diabetes (65), obesity (36), and fatty liver disease (37, 66), as well as cancer (67, 68), and Alzheimer disease (35). However, undesirable side effects of targeting LXR using ligands—such as elevated liver triglycerides via LXR-dependent activation of sterol regulatory-element binding proteins—have hindered the clinical utility of compounds targeting LXRα (69-71). Therefore, finding ways to selectively activate (or repress) LXRα targets genes via changes in LXRα phosphorylation could represent a new therapeutic strategy because alterations in LXRα phosphorylation elicit different patterns of gene expression. This is consistent with the finding that phosphorylation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ at S273 in the hinge region by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 changes the expression of specific genes involved in insulin sensitivity (72). In fact, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands that block cyclin-dependent kinase 5–mediated phosphorylation of the receptor have potent anti-diabetic activity through selective changes in gene expression, suggesting the possibility of novel pharmacology achieved by modulating phosphorylation of nuclear receptors (72, 73). We have reported that we can stimulate the nonphosphorylated form of LXRα pharmacologically by blocking the upstream kinase (eg, CK2) or using a combination of LXRα ligands, such as T0901317 and 9cRA (22). To circumvent systemic side effects of LXR activation, site-specific delivery of LXRα ligands and/or kinase inhibitors that block phosphorylation could be accomplished using nanoparticles. Nanomedicine using LXRα ligands has demonstrated success in treating atherosclerosis in a mouse model while minimizing systemic effects in the liver (74). However, a better understanding of the complex activities of LXRα pS196 in pathological contexts, especially in models that recapitulate human pathophysiology, is necessary to develop alternative targeted therapies.

Conclusions and Future Directions

We have shown that LXRα phosphorylation at S196 plays a key role in the control of LXRα transcriptional activity in cardiometabolic disease. One overarching theme from these studies is that pS196 reprograms the LXR-modulated transcriptome, and this appears distinct from the LXR transcriptome in response to ligand (28, 31). For example, Gage et al found that the majority of the genes in the macrophage transcriptional response that were sensitive to the LXRα phosphomutant were observed in the absence of LXR ligand stimulation (28). This suggest that environmental cues such as diet are perceived by LXR phosphorylation. These findings are also supported by work from Ramón-Vázquez and colleagues in immortalized BMDMs from LXR-deficient mice reconstituted with either LXRα or LXRβ that found most of the gene expression differences were seen when receptors were expressed rather than with pharmacological activation of LXR (75). In addition, comparison of gene expression profiles between macrophages from the plaque and macrophages from the visceral adipose tissue from the same mouse were nonoverlapping (30), highlighting the role of the local tissue microenvironment in determining gene expression managed by LXRα.

Our studies have established the physiological relevance of LXRα phosphorylation in cardiometabolic diseases, but several questions remain. For example, which kinase(s), CK2 or protein kinase A, phosphorylate LXRα in vivo, and is this dependent on the diet or cell type? To address these questions, we could use genetics and pharmacological manipulation via kinase conditional knockout mice, and kinase inhibitors. Another remaining question is how does LXRα S196A induce such a dramatic change in transcription? LXRα S196A can selectively occupy certain genes via preferential interaction with coregulators (22, 31). This reinforces work on LXRβ phosphorylation at S426 by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II γ, leading to the derepression of inflammatory genes via the release of coronin 2, a component of the NCoR repression complex (76). But are these mechanisms the exception or the rule? To gain insight into this question, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing studies of LXRα WT and LXRα S196A on dietary changes, as well as characterization of the LXRα S196 phosphocistrome using LXRα phosphospecific antibody in macrophages and liver, could inform LXRα phosphorylation-dependent gene regulatory mechanisms by identifying potential collaborating transcription factors.

We are also interested in applying the LXRα S196A mouse model to other diseases linked to LXRα signaling, including neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer (77). Additionally, an atlas of LXRα phosphorylation in normal and diseased human tissues would help inform homeostatic or pathological states in which LXRα phosphorylation could be relevant. Together, such studies would reveal mechanisms underlying LXRα phosphorylation-dependent gene expression, and inform physiological settings in which LXRα phosphorylation is important.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01HL117226 to M.J.G. and E.A.F.), the American Heart Association (postdoctoral fellowship 19POST34410010 to M.V.), the Jan Vilcek/David Goldfarb Fellowship (to M.V.), the British Heart Foundation (Project Grants PG/13/10/30000 to I.P.T. and PG/16/87/32492 to M.G. and I.P.T.), the Medical Research Council (New Investigator Grant G0801278 to I.P.T.), the University College of London (Grand Challenges PhD Studentship to I.P.T. and N.B.), and National Institutes of Health (P01HL131481 to E.A.F. and M.J.G. and R01HL084312 to E.A.F.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ATM

adipose tissue macrophage

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BMDM

bone marrow–derived macrophage

- Ces1f

carboxylase 1F

- CK2

casein kinase 2

- FoxM1

forkhead box protein M1

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HFHC

high-fat, high-cholesterol

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LDLR

LDL receptor

- LXR

liver X receptor

- LXRE

LXR response element

- M-S196ALdlr-KO

mouse model expressing LXRα S196A in myeloid cells on LDLR-deficient atherosclerotic-prone background

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NCoR

nuclear receptor co-repressor

- Pol II

RNA polymerase II

- pS196

S196 phosphorylation

- pWAT

perigonadal white adipose tissue mass

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- S196

serine 196

- S196A

serine-to-alanine mutation at Ser196

- S198

serine198

- TBLR1

transducin β-like 1 X-linked receptor 1

- WT

wild-type

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Data Availability. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Calkin AC, Tontonoz P. Transcriptional integration of metabolism by the nuclear sterol-activated receptors LXR and FXR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):213-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spann NJ, Garmire LX, McDonald JG, et al. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 2012;151(1):138-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Apfel R, Benbrook D, Lernhardt E, Ortiz MA, Salbert G, Pfahl M. A novel orphan receptor specific for a subset of thyroid hormone-responsive elements and its interaction with the retinoid/thyroid hormone receptor subfamily. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(10):7025-7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zelcer N, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):607-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Janowski BA, Willy PJ, Devi TR, Falck JR, Mangelsdorf DJ. An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR alpha. Nature. 1996;383(6602):728-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fradera X, Vu D, Nimz O, et al. X-ray structures of the LXRalpha LBD in its homodimeric form and implications for heterodimer signaling. J Mol Biol. 2010;399(1):120-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boergesen M, Pedersen TÅ, Gross B, et al. Genome-wide profiling of liver X receptor, retinoid X receptor, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α in mouse liver reveals extensive sharing of binding sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(4):852-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wagner BL, Valledor AF, Shao G, et al. Promoter-specific roles for liver X receptor/corepressor complexes in the regulation of ABCA1 and SREBP1 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(16):5780-5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sever R, Glass CK. Signaling by nuclear receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(3):a016709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glass CK, Saijo K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(5):365-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chinenov Y, Gupte R, Rogatsky I. Nuclear receptors in inflammation control: repression by GR and beyond. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;380(1-2):55-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ghisletti S, Huang W, Ogawa S, et al. Parallel SUMOylation-dependent pathways mediate gene- and signal-specific transrepression by LXRs and PPARgamma. Mol Cell. 2007; 25(1):57-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee SK, Kim JH, Lee YC, Cheong J, Lee JW. Silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptors, as a novel transcriptional corepressor molecule of activating protein-1, nuclear factor-kappaB, and serum response factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(17):12470-12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joseph SB, Castrillo A, Laffitte BA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9(2):213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ogawa S, Lozach J, Benner C, et al. Molecular determinants of crosstalk between nuclear receptors and toll-like receptors. Cell. 2005;122(5):707-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prüfer K, Boudreaux J. Nuclear localization of liver X receptor alpha and beta is differentially regulated. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100(1):69-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Watanabe Y, Tanaka T, Uchiyama Y, et al. Establishment of a monoclonal antibody for human LXRα: detection of LXRα protein expression in human macrophages. Nucl Recept. 2003;1(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lalevée S, Ferry C, Rochette-Egly C. Phosphorylation control of nuclear receptors. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;647:251-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berrabah W, Aumercier P, Lefebvre P, Staels B. Control of nuclear receptor activities in metabolism by post-translational modifications. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(11):1640-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Becares N, Gage MC, Pineda-Torra I. Posttranslational modifications of lipid-activated nuclear receptors: focus on metabolism. Endocrinology. 2017;158(2):213-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Torra IP, Ismaili N, Feig JE, et al. Phosphorylation of liver X receptor alpha selectively regulates target gene expression in macrophages. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(8):2626-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen M, Bradley MN, Beaven SW, Tontonoz P. Phosphorylation of the liver X receptors. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(20):4835-4841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamamoto T, Shimano H, Inoue N, et al. Protein kinase A suppresses sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1C expression via phosphorylation of liver X receptor in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(16):11687-11695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anthonisen EH, Berven L, Holm S, Nygård M, Nebb HI, Grønning-Wang LM. Nuclear receptor liver X receptor is O-GlcNAc-modified in response to glucose. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(3):1607-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li X, Zhang S, Blander G, Tse JG, Krieger M, Guarente L. SIRT1 deacetylates and positively regulates the nuclear receptor LXR. Mol Cell. 2007;28(1):91-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu C, Hussein MA, Shrestha E, et al. Modulation of macrophage gene expression via liver X receptor α serine 198 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(11):2024-2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gage MC, Becares N, Louie R, et al. Disrupting LXRα phosphorylation promotes FoxM1 expression and modulates atherosclerosis by inducing macrophage proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(28):E6556-E6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shrestha E, Voisin M, Barrett TJ, et al. Phosphorylation of LXRα impacts atherosclerosis regression by modulating monocyte/macrophage trafficking. bioRxiv. 2018:363366. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Voisin M, Shrestha E, Rollet C, et al. Inhibiting LXRα phosphorylation in hematopoietic cells reduces inflammation and attenuates atherosclerosis and obesity. bioRxiv. 2020:939090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Becares N, Gage MC, Voisin M, et al. Impaired LXRα phosphorylation attenuates progression of fatty liver disease. Cell Rep. 2019;26(4):984-995.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lou X, Toresson G, Benod C, et al. Structure of the retinoid X receptor α-liver X receptor β (RXRα-LXRβ) heterodimer on DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(3):277-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanyal AJ. Past, present and future perspectives in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(6):377-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):123-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hong C, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors in lipid metabolism: opportunities for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(6):433-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beaven SW, Matveyenko A, Wroblewski K, et al. Reciprocal regulation of hepatic and adipose lipogenesis by liver X receptors in obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2013;18(1):106-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wouters K, van Bilsen M, van Gorp PJ, et al. Intrahepatic cholesterol influences progression, inhibition and reversal of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in hyperlipidemic mice. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(5):1001-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moylan CA, Pang H, Dellinger A, et al. Hepatic gene expression profiles differentiate presymptomatic patients with mild versus severe nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59(2):471-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perissi V, Aggarwal A, Glass CK, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG. A corepressor/coactivator exchange complex required for transcriptional activation by nuclear receptors and other regulated transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116(4):511-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jakobsson T, Venteclef N, Toresson G, et al. GPS2 is required for cholesterol efflux by triggering histone demethylation, LXR recruitment, and coregulator assembly at the ABCG1 locus. Mol Cell. 2009;34(4):510-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lian J, Nelson R, Lehner R. Carboxylesterases in lipid metabolism: from mouse to human. Protein Cell. 2018;9(2):178-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(10):709-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee SD, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors at the intersection of lipid metabolism and atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):29-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abram CL, Roberge GL, Hu Y, Lowell CA. Comparative analysis of the efficiency and specificity of myeloid-Cre deleting strains using ROSA-EYFP reporter mice. J Immunol Methods. 2014;408:89-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gormally MV, Dexheimer TS, Marsico G, et al. Suppression of the FOXM1 transcriptional programme via novel small molecule inhibition. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cochain C, Vafadarnejad E, Arampatzi P, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the transcriptional landscape and heterogeneity of aortic macrophages in murine atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2018;122(12):1661-1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fernandez DM, Rahman AH, Fernandez NF, et al. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nat Med. 2019;25(10):1576-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin JD, Nishi H, Poles J, et al. Single-cell analysis of fate-mapped macrophages reveals heterogeneity, including stem-like properties, during atherosclerosis progression and regression. JCI Insight. 2019;4(4):e124574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beattie L, Sawtell A, Mann J, et al. Bone marrow-derived and resident liver macrophages display unique transcriptomic signatures but similar biological functions. J Hepatol. 2016;65(4):758-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Takezawa R, Watanabe Y, Akaike T. Direct evidence of macrophage differentiation from bone marrow cells in the liver: a possible origin of Kupffer cells. J Biochem. 1995;118(6):1175-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Trogan E, Choudhury RP, Dansky HM, Rong JX, Breslow JL, Fisher EA. Laser capture microdissection analysis of gene expression in macrophages from atherosclerotic lesions of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(4):2234-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Viola A, Munari F, Sánchez-Rodríguez R, Scolaro T, Castegna A. The metabolic signature of macrophage responses. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Winkels H, Ehinger E, Ghosheh Y, Wolf D, Ley K. Atherosclerosis in the single-cell era. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2018;29(5):389-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hill AA, Reid Bolus W, Hasty AH. A decade of progress in adipose tissue macrophage biology. Immunol Rev. 2014;262(1):134-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chait A, Bornfeldt KE. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: is there a role for hyperglycemia? J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S335-S339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Katakami N. Mechanism of development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25(1):27-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nicholls SJ, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, et al. Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2078-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Parathath S, Grauer L, Huang LS, et al. Diabetes adversely affects macrophages during atherosclerotic plaque regression in mice. Diabetes. 2011;60(6):1759-1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hussein MA, Shrestha E, Ouimet M, et al. LXR-mediated ABCA1 expression and function are modulated by high glucose and PRMT2. PloS One. 2015;10(8):e0135218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lieu HD, Withycombe SK, Walker Q, et al. Eliminating atherogenesis in mice by switching off hepatic lipoprotein secretion. Circulation. 2003;107(9):1315-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lee CD, Folsom AR, Nieto FJ, Chambless LE, Shahar E, Wolfe DA. White blood cell count and incidence of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke and mortality from cardiovascular disease in African-American and white men and women: atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(8):758-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Murphy AJ, Akhtari M, Tolani S, et al. ApoE regulates hematopoietic stem cell proliferation, monocytosis, and monocyte accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):4138-4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. A-Gonzalez N, Bensinger SJ, Hong C, et al. Apoptotic cells promote their own clearance and immune tolerance through activation of the nuclear receptor LXR. Immunity. 2009;31(2):245-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cao G, Liang Y, Broderick CL, et al. Antidiabetic action of a liver X receptor agonist mediated by inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(2):1131-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhou J, Febbraio M, Wada T, et al. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARgamma in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):556-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lin CY, Vedin LL, Steffensen KR. The emerging roles of liver X receptors and their ligands in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20(1):61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lin CY, Gustafsson JÅ. Targeting liver X receptors in cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):216-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Groot PH, Pearce NJ, Yates JW, et al. Synthetic LXR agonists increase LDL in CETP species. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(10):2182-2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Joseph SB, Laffitte BA, Patel PH, et al. Direct and indirect mechanisms for regulation of fatty acid synthase gene expression by liver X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(13):11019-11025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schultz JR, Tu H, Luk A, et al. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14(22):2831-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Choi JH, Banks AS, Estall JL, et al. Anti-diabetic drugs inhibit obesity-linked phosphorylation of PPARgamma by Cdk5. Nature. 2010;466(7305):451-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Choi JH, Banks AS, Kamenecka TM, et al. Antidiabetic actions of a non-agonist PPARγ ligand blocking Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation. Nature. 2011;477(7365):477-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhang XQ, Even-Or O, Xu X, et al. Nanoparticles containing a liver X receptor agonist inhibit inflammation and atherosclerosis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4(2):228-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ramón-Vázquez A, de la Rosa JV, Tabraue C, et al. Common and differential transcriptional actions of nuclear receptors liver X receptors α and β in macrophages. Mol Cell Biol. 2019;39(5):e00376-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Huang W, Ghisletti S, Saijo K, et al. Coronin 2A mediates actin-dependent de-repression of inflammatory response genes. Nature. 2011;470(7334):414-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zelcer N, Khanlou N, Clare R, et al. Attenuation of neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease pathology by liver X receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(25):10601-10606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]