Abstract

Purpose:

More than 25% of US adults experience mental health or substance use conditions annually, yet less than half receive treatment. This study explored how rural participants with behavioral health conditions pursue and receive care, and it examined how these factors differed across American Indian (AI) and geographic subpopulations.

Methods:

We undertook a qualitative follow-up study from a statewide survey of unmet mental health and substance use needs in South Dakota. We conducted semi-structured phone interviews with a purposive sample of key informants with varying perceptions of need for mental health and substance use treatment.

Results:

We interviewed 33 participants with mental health (n = 18), substance use (n = 9), and co-occurring disorders (n = 6). Twenty participants (61.0%) lived in rural communities that did not overlap with AI tribal land. Twelve participants (34.3%) were AI, 8 of whom lived on a reservation (24.2%). The discrepancy between actual and perceived treatment need was related to how participants defined mental health, alcohol, and drug use “problems.” Mental health disorders and excessive alcohol consumption were seen as a normal part of life in rural and reservation communities; seeking mental health care or maintaining sobriety was viewed as the result of an individual’s willpower and frequently related to a substantial life event (eg, childbirth). Participants recommended treatment gaps be addressed through multicomponent community-level interventions.

Discussion:

This study describes how rural populations view mental health, alcohol, and drug use. Enhancing access to care, addressing discordant perceptions, and improving community-based interventions may increase treatment uptake.

Keywords: alcohol abuse, drug abuse, mental health, policy, qualitative research

Nationwide, more than 25% of adults contend with a mental health or substance use disorder annually, yet less than half receive treatment.1,2 Specific population groups, including individuals in rural communities and/or of American Indian (AI) ethnicity, may experience even greater treatment gaps for these conditions.2–5 Rural adults, who comprise approximately 20% of the US population, experience disparities in detection and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders compared to those who reside in urban settings.6–8 For example, Ziller et al7 found that approximately 1 out of 3 (32%) urban mental health service users reported 1 or more office visits as compared to 1 out of 5 (23%) rural mental health service users. In general, rural residents with mental health disorders are more likely to have co-occurring substance abuse disorders, and they experience a higher prevalence of risk factors such as poor health status and poverty.9 AI subpopulations, who may also reside in rural areas, experience high rates of mental health disorders, including post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidal behaviors,5,10 and they are more likely to need treatment for alcohol or drug abuse.11 In order to improve the health of rural and underserved populations, it is necessary to address these gaps in behavioral health service treatment.4,12

Behavioral health disparities for rural populations may be driven by a combination of access barriers and personal perceptions and beliefs.8,13 Distance to services, lacking or limited awareness of available resources, and perceptions of provider shortages have been identified as barriers in rural residents’ ability to seek care for mental health issues.14–16 Treatment gaps may also be exacerbated by perceptions that the available care is below quality standards,14 or by prevailing stigma against mental health and substance use disorders.17–19 There is also evidence that rural residents must reach a high need-for-care threshold before seeking care.13,20 A recent survey of more than 7,675 households in the rural state of South Dakota found substantial discordance between respondents with a positive clinical screen for behavioral health conditions and their perceived need for treatment. In this study, 12.2% screened positive for a mental health condition and 42.3% screened positive for alcohol or drug abuse; however, fewer than 4 out of 10 respondents (36.2%) who screened positive for mental health conditions and only 2 out of 100 (1.9%) who screened positive for alcohol or drug abuse reported a perceived need for treatment.21

If there is substantial discordance between clinical need and individuals’ perceived need for care, policy initiatives designed to improve health care delivery by increasing access may be hindered. This perspective is particularly salient given the changing landscape of behavioral health services coverage and care delivery. Implementation of the Affordable Care Act, in conjunction with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, has the potential to expand and support access to and treatment for behavioral health disorders. However, if rural populations do not perceive a need for treatment, policy initiatives designed to expand access and improve insurance benefits for behavioral health may have a relatively small impact.

To better understand how rural populations perceive treatment gaps for behavioral health conditions, we undertook a qualitative study of residents in South Dakota who screened positive for mental health and substance abuse disorders on a prior statewide health survey.21 South Dakota is 1 of 15 states in the United States that is more than 50% rural,22 and it is also home to 9 reservations and a sizeable AI population—almost 10% of its residents.23 Our intent was to explore respondents’ mental and behavioral health challenges, any treatment or support they sought, and the reasoning behind their decisions. We were also interested in differences in perspective by ethnicity (ie, AI vs white) and geographic region (eg, rural land not overlapping with tribal lands vs reservation areas). This research complements our larger, statewide survey of unmet mental health and substance use needs in South Dakota.21

Methods

We recruited participants from those completing the South Dakota Health Survey (SDHS) who indicated willingness to participate in additional research. We briefly summarize the methods for the SDHS here; a full description is available elsewhere.21 The SDHS was a statewide, multimode survey study designed to determine the population prevalence of unmet behavioral health needs across the state.21 SDHS questions assessed behavioral health condition prevalence, health services use, barriers to care, and demographic characteristics of respondents. Validated questions and response scales were used when feasible (eg, patient health questionnaire for depression and anxiety; primary care PTSD screen; Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, AUDIT-C, screen for alcohol consumption; and measures regarding drug use from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health).24–26

SDHS surveys were administered by mail, telephone, and in person to over 16,000 households across South Dakota, with oversampling in rural and AI reservation areas. Rurality was defined using the ZIP code version of the Rural-Urban Commuting Areas (RUCAs) taxonomy to cluster respondents into geographic categories based on population size and commuting patterns.27,28 For this qualitative study, urban included metropolitan cores and commuting patterns to areas with populations of 50,000 or more residents. Rural was defined as areas with 49,999 or fewer residents that did not overlap with AI tribal land. We also created a distinct “reservation” category for ZIP codes fully or partially overlapping with AI tribal land. Prior to fielding surveys in tribal/reservation areas, study investigators conducted outreach and secured study approval from 7 of the 9 tribes in South Dakota; participating tribes provided the research team with a Tribal Council Resolution endorsing the study or a letter of support from the Tribal Institutional Review Board or the Tribal Chairman depending on standard processes. The SDHS and follow-up interviews were only conducted in tribal areas where approval was obtained.

Data from the SDHS provided critical information on unmet mental health and substance use needs across the state, but it also raised some important questions that the survey itself could not answer. Most notably, analysis of SDHS results found that the majority (64%) of those who screened positive for depression, anxiety, or PTSD also reported that they had not needed any mental health care in the last year. Similarly, 93% of those who screened as very heavy drinkers (AUDIT-C scores of 9 or more) reported no perceived need for alcohol use treatment. Indeed, the percent of people who claimed they needed mental health care in the last year (9.6%) was actually lower than the percent who reported having been to the ER for a mental health condition in the same time period (11.2%).

We wanted to understand the discordance between results from our mental health and substance use screenings and respondents’ self-assessments of whether they needed care. To explore this discordance, we identified a subset of survey respondents and conducted key informant interviews designed to elicit in-depth information on the relationship between behavioral health challenges, perceived need, and whether someone actually received care. The project was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 9940).

Participants

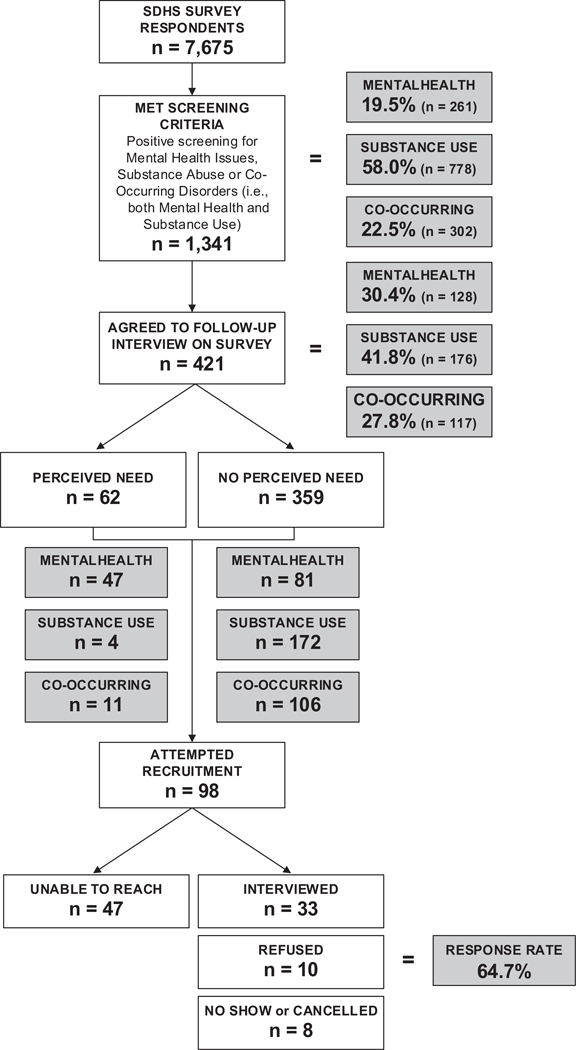

We used a 3-step process to identify participants (Figure 1). First, we identified respondents who indicated a willingness to participate in additional studies (n = 1,922 of 7,675). Compared to the overall sample of SDHS responders, willing respondents were more likely to be female, younger, non white, and more likely to have screened positive for a mental health condition. Second, we clustered willing respondents with positive screens (n = 421) into subcategories based on their screening results (ie, mental health, substance use, co-occurring disorders) and their perceived need for treatment (ie, yes need vs no need). For cells with over 200 willing respondents, we used random sampling to identify a subset of participants to recruit for qualitative interviews. Finally, we recruited participants across sampling categories, monitoring data collection to ensure our final sample captured sufficient variation in geography (rural, urban, reservation), gender, age (18–34, 35–64, over 65), and ethnicity/race (AI, white). (See Table 1.)

Figure 1.

Participant Selection and Recruitment Process for Key Informant Interviews.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 33)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 5 (15.2) |

| 35–64 | 22 (66.7) |

| 65 and older | 6 (18.2) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 13 (40.0) |

| Female | 20 (60.0) |

| Race/ethnicitya | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 21 (63.6) |

| AI | 10 (30.3) |

| Other | 2 (6.0) |

| Residential status | |

| Live alone | 12 (36.4) |

| Live with spouse | 15 (45.5) |

| Other | 6 (18.2) |

| Employment status | |

| Not currently employed | 8 (24.2) |

| Employed <20 hours/week | 2 (6.1) |

| Employed 20–30 hours/week | 5 (15.2) |

| Employed 40 hours or more/week | 13 (39.4) |

| Retired | 5 (15.2) |

| Geographyb | |

| Urban | 5 (15.2) |

| Rural | 20 (60.6) |

| Reservation | 8 (24.2) |

| Income (% FPL) | |

| ≤50% FPL | 3 (9.1) |

| 50%−138% FPL | 7 (21.2) |

| 138%−250% FPL | 7 (21.2) |

| 250%−400% FPL | 4 (12.1) |

| >400% FPL | 6 (18.2) |

| Missing (no income provided) | 6 (18.2) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 5 (15.2) |

| High school diploma or GED | 13 (39.4) |

| Vocational or 2-year degree | 9 (27.3) |

| 4-year college degree | 2 (6.1) |

| Advanced or graduate degree | 4 (12.1) |

| Screening status | |

| Mental health only | 18 (54.5) |

| Substance abuse only | 9 (27.3) |

| Co-occurring conditions | 6 (18.2) |

No participants reported Hispanic/Latino or black ethnicity.

Rurality determined using RUCA codes.27,28 Urban includes metropolitan cores and commuting patterns to areas with populations of 50,000 or more. Rural includes areas with populations of 49,999 or fewer, excluding AI tribal lands. The reservation category is distinct from the rural geographic cluster and includes zip codes fully or partially overlapping with AI tribal lands.

Data Collection

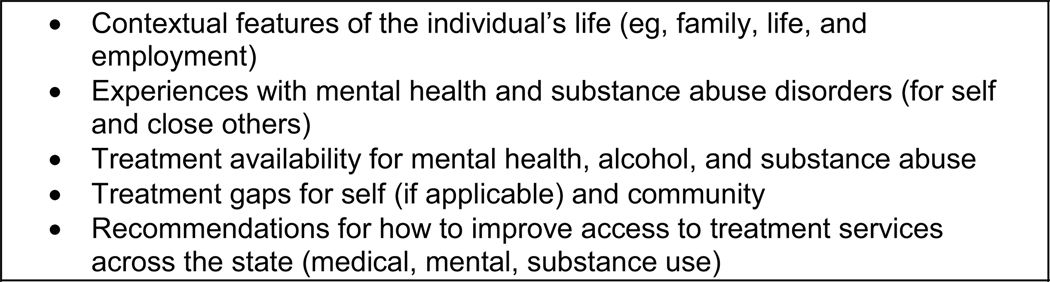

Trained research assistants contacted participants by phone between July and November 2014 to obtain informed consent and conduct interviews following a semi-structured guide. Figure 2 summarizes the domains covered in the guide, with the full instrument available in Appendix A (online only).

Figure 2.

Domains of the Semi-structured Interview Guide.

Of the 98 participants identified, 47 could not be reached despite multiple attempts and 33 agreed to participate (64.7% response rate; Figure 1). Interviews lasted 30–60 minutes and were audio-recorded, transcribed, and transferred to ATLAS.ti (version 7, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for data coding and analysis. Participants received an honorarium of $20 that was mailed upon interview completion.

Data Analysis

A multidisciplinary team with expertise in qualitative research, mental health, rural health, AI populations, and health services research analyzed transcripts using a content analysis framework.29 We identified codes inductively using the first few interviews to contextualize emergent themes. A core team coded subsequent transcripts; an oversight team of investigators reviewed emergent results and made changes to the coding dictionary to accommodate new information as necessary. To better understand treatment gaps, we analyzed the narratives of participants with discordance around screening and need, as well as the counternarratives—interviews from participants who obtained care for their behavioral health conditions. Our intent was to identify the tipping point or catalyst for seeking care. We collected data until we reached saturation across the sample, the point at which findings repeat or reoccur.30,31

Results

We interviewed 33 participants with mental health (n = 18), substance use (n = 9), and co-occurring disorders (n = 6). Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1; Table 2 presents a breakdown of participants by positive screen, perceived need, and geographic region. Twenty participants (61%) lived in rural communities that did not overlap with AI tribal land. Twelve participants (34.3%) were AI, 8 of whom currently lived on a reservation (24.2%). Two-thirds (66%) of the participants were between 35 and 64 years of age. Similar to the overall survey sample, we found high rates of discordance between screening results and need: despite screening positive, 58% (n = 19) of our participants reported no perceived need for care (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceived Need and Geographic Distribution in Participants That Screened Positive for Mental Health, Substance Use, or Co-Occurring Disorders, n(%)

| Positive Screen | Overall (N = 33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health (N = 18) | Substance Use (N = 9) | Co-Occurring (N = 6) | ||

| Perceived need | ||||

| Yes | 10 (30) | 0(0) | 4 (12)a | 14 (42) |

| No | 8(24) | 9(27) | 2(6) | 19 (58) |

| Geography | ||||

| Urban | 1 (3) | 3(9) | 1 (3) | 5(15) |

| Rural | 13 (39) | 4(12) | 3(9) | 20 (61) |

| Reservation | 4(12) | 2(6) | 2 (6) | 8(24) |

One participant perceived a need for mental health and substance use treatment, 3 participants perceived a need for mental health treatment but not for substance use treatment.

Two broad constructs emerged as critical to understanding treatment gaps: (1) how the “problem” was defined shaped an individual’s perceptions of need and (2) tipping points that encouraged individuals to seek care. We describe these concepts in relation to the distinct narratives that emerged around mental health, alcohol and drug use, and highlight participant recommendations for how to reduce the gap between perceived need and treatment-seeking behaviors.

Understanding the Treatment Gap for Mental Health

Defining the Problem

The ways in which participants understood and defined mental health problems impacted their treatment-seeking behavior. Many rural participants viewed mental health conditions as a normal part of life, rather than as something that could be treated. This sense of resignation was described by a 57-year-old white woman who stated, “I know people who are depressed, I don’t think they’re getting care for depression. I just think it’s life and it has been out here for so many years.” Mental health conditions were also commonly defined as either a temporary response to a traumatic situation or as a “personal problem,” not as a disease.

Subgroup differences suggest that the treatment gap might be influenced by both gender and age. Women more often described their own depression and/or anxiety as a pervasive and persistent issue rather than as a reaction to a specific event. For example, one 35-year-old AI woman explained:

I do have mental health issues. I need to see a counselor on a regular basis, and I should be taking prescription medications, but I do not take them, just because of the fact that I can’t afford them.

All participants under the age of 45 (n = 8) perceived mental health conditions as a disease or situational issue, where seeking help was warranted:

Just because you go to a psychologist or counselor doesn’t mean you’re crazy. It just means you need some help sorting things out and figuring out what type of action you should be taking for the situations that you’re involved with (42-year-old white man).

Although younger participants indicated that mental health disorders are something that can be treated, some participants viewed depression, and even suicide, as a normal part of life. As one respondent matter-of-factly told us, “numerous relatives and friends did pass away here; [they] were killed in car accidents or they committed suicide” (65-year-old AI man).

Anonymity and Stigma (Self- and Other-Directed)

All participants with a discordance between positive screen and perceived need (n = 8) for mental health treatment noted that stigma featured prominently in the community discourse. This was especially true for male participants. One male with mental health needs who lived on a reservation noted he would not seek treatment because “everyone would know” and then think of him as a “fruitcake.” Another male participant who screened positive for mental health issues but did not perceive a need for treatment described a friend with a mental health condition as someone who was “putting on an act.” Participants who lacked personal experience with mental health issues speculated that community members might avoid care because of challenges associated with anonymity and perceived stigma with having mental illness:

[A barrier is] everybody knowing. [It’s a] small community. It doesn’t take long for word to get around. A matter of fact, if I take an ambulance run by the time I get back half the town knows about it—in detail. I mean it surprises the heck out of me how we can run to [larger city] and back which takes about 4–1/2 hours and I’ll get back and go to the grocery store and people will ask me ‘Well, how’s so and so doing?’ (58-year-old white man).

One man mentioned that in some communities with a large military presence, there was no stigma associated with PTSD treatment for veterans. However, the participant also noted that this compassion does not extend to nonmilitary personnel who might have a mental health condition. Lack of anonymity was less of an issue for urban participants as only one nonrural participant mentioned privacy concerns.

The majority of participants cited denial as a primary factor that might prevent a community member from seeking care for a mental health condition. A few framed this refusal as coming from a place of unrelenting pride:

Possibly they feel that it’s something that they can live with. If they’re older they’ve gotten through it—in this community especially—they may think, ‘I don’t need help I can get through this. I’ve had this condition all my life and I’ve managed.’ We’re not talking quality of life.... We’re talking about pride (57-year-old white woman).

Tipping Points

Those who received treatment for mental health conditions reported varied motives. A few sought treatment after encouragement from family and friends. Women more frequently reported that they recognized their problem on their own and took action; one woman described talking with her doctor after viewing a billboard that identified her symptoms as depression. In contrast, the men who received care for a mental health condition described it as a component of a larger treatment regimen, for example, for depression related to physical pain from an injury. Although urban participants also cited stigma as a barrier to treatment, more traditional access concerns, including lack of insurance and the quality of available care, were more prevalent.

Understanding the Treatment Gap for Alcohol

Defining the Problem

In parallel with mental health perceptions, willingness to seek treatment for alcohol disorders was strongly influenced by the ways in which the “problem” was defined. Participants noted the threshold for alcohol consumption was high across urban, rural, and reservation communities. Participant-defined threshold for abuse far exceeded the standard screening definition and included: (1) losing control of oneself under the influence and causing another harm (eg, “trampling on other people’s rights”); (2) neglecting responsibility by performing poorly at work or shirking family duties; (3) drinking excessively such as “first thing in the morning” or having a notably high number of drinks per day; and (4) receiving a legal infraction for alcohol consumption. One 75-year-old AI man summed this perspective up in his statement: “If [drinking] cuts in on your normal way of life, that’s abuse.”

Threaded through participants’ definitions of alcohol abuse were comments around how one was functioning relative to the others around them. Participants appeared to have a skewed sense of what was an acceptable level of alcohol consumption based on their defined thresholds. For example, one woman, whose survey indicated she consumed 10 drinks a day, explained why she feels as though she does not have a drinking problem:

I think some of it is like, ‘Oh, I’ve never gotten in trouble with the law and when I do drink I’m at home...I’m not out and about, causing problems or going out and driving around.’ And like I say, I haven’t viewed it as a problem (37-year-old white woman).

Many participants articulated that drinking started very young. One 59-year-old white woman summed up alcoholism in her community by stating “genetics cocks the gun, and the environment pulls the trigger.” One 74-year-old white man who had been raised on a reservation commented, “That was just the norm. When you got to be in the eighth grade, you started going to dances and drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. That was just what life was.”

Stigma (Self- and Other-Directed)

Despite a consistent acknowledgment throughout the interviews that excessive drinking was a problem, many participants with discordance between screening and perceived need discussed stigma around seeking treatment for alcohol abuse. Though no one directly cited stigma as a concern, participants indicated that lacking control over one’s drinking was viewed as a sign of weakness.

The construct of stigma manifested itself in narrative subgroup differences. Though excessive alcohol consumption was a common narrative for both white and AI participants, there were pervasive stereotypes around excess drinking in reservation communities. AI participants articulated feeling shame over seeing members of their community intoxicated. Some participants indicated that there were more infractions for public intoxication on the reservation because alcohol is illegal there.

Tipping Points

None of our participants who screened positive for alcohol abuse identified a need for treatment. However, participants shared stories of tipping points when they or others worked to stop abusing alcohol. These tipping points were often described as a piece of a larger narrative involving the willpower to quit on one’s own.

I was drinking too much and I’d get blackouts and I decided one day, it was on my birthday and [I] was drinking with friends and I just decided that day I was done and I quit drinking and never had a drop for 5 years. It just got to be too much, I was drinking too much and so I decided on my own I was going to quit, so I did. Same way I quit cigarettes (67-year-old white man).

Many described an independent path to sobriety, often inspired by a change in circumstances that required additional responsibility, like having a child. One 38-year-old man stated, “I’d seen my mom quit, and a few other family members quit drinking. I was the only one still making an ass out of myself. And then I had kids.” One 85-year-old AI woman mentioned that she tells younger members of her community that treatment is futile without internal willpower, “That’s what I tell these young ones. ‘You don’t have to go to treatment. Just make up your mind to quit.’ Sometimes, they go to treatment and it don’t do any good. They come out and start right in again.”

Another impetus for treatment was when it was mandated by the court system. One 65-year-old AI male commented, “Over the years I’ve been in treatment about 4 times...because they were mandatory from the court...a lot of them had to do with DUIs.” Court mandated treatment was not a panacea; the same participant indicated that despite 4 times in treatment, he was only inspired to quit on his own when he became a husband and father. Some participants noted that law enforcement played an important role in enforcing appropriate behaviors by removing “drunk idiots from the streets.” Others were more skeptical, noting that the government had “screwed it up” by setting the legal driving limit “ridiculously low,” that revoking licenses had serious consequences on peoples’ ability to be employed, or that police intervention worsens drinking behavior by moving excessive consumption from the bars and businesses to the home.

Our police force has just changed but they were a negative because they sat and watched who came out of the bars and ran the bars out of business because they would stop everybody and get them drunk driving tickets. People still drink but they buy the bottle and they drink at home so they force them not to be a social drinker, just an at-home drinker (71-year-old AI woman).

The definition of sobriety among participants who described quitting drinking was not synonymous with abstinence. Many of those who explained that they had overcome their problems were still drinking, just less; this was often within the bounds of what was not considered abuse as defined by the aforementioned community norms. As a counter-perspective, the more urban respondents in our sample all mentioned that there were treatment centers in town; however, access to a facility varied across rural participants, with many indicating that one would have to travel to a more urban area for help.

Understanding the Treatment Gap for Drugs

Defining the Problem

Participants reported far fewer first-person experiences with drug abuse and had “problem” definitions more aligned with clinical screenings. These findings are consistent with the overall SDHS results in which only 8% of all responders reported using drugs.21 Approximately half of the participants said that any drug use is considered abuse. One 32-year-old white man commented, “Once you start using [drugs] it’s so mind-altering. You’re abusing it the second you start.” Others equated drug abuse with alcohol abuse: as long as it was not interfering with one’s ability to function, it was not abuse.

The majority of participants mentioned that drugs, particularly methamphetamines, were a pervasive issue in their communities. Some reflected that this abuse was a response to environmental context. One 60-year-old AI man explained: “Unemployment [is contributing to my daughter’s abuse]. She’s [just] trying to survive.” We found some evidence that the level of acceptance for some drug use was correlated with age; younger participants identified recreational use as more acceptable. Participants also made a notable distinction between marijuana and other drugs, with use of marijuana being much more acceptable.

Stigma (Self- and Other-Directed)

Though no one described personally experiencing discrimination for drug use, participant comments revealed that stigma against drug users was common and likely played a role in impeding access to care. One 58-year-old white man commented, “I think the community in general doesn’t accept drug abuse at all. I mean its taboo and if it gets to be known that they’re using drugs and whatnot I think the community in general shuns them.”

Tipping Points

Only one participant admitted to seeking treatment for drug abuse. As with alcohol abuse, the catalyst for the treatment was discovering she was pregnant with her first child. This respondent received substance abuse treatment in a residential facility for 2 weeks and had since maintained sobriety due to “her own willpower.”

Closing the Gap: Participant Recommendations

Participants had several suggestions to improve treatment and prevention of these behavioral health disorders. Many indicated that addressing traditional access barriers would reduce gaps, for example, by building local facilities in rural areas, increasing the number of providers, and ensuring that services aligned with cultural traditions. However, participants emphasized the importance of 2 upstream interventions: community education and environmental change.

Community Education

Participants suggested interventions to address the cognitive dissonance around screening results and perceived need for care. Participants indicated that one of the biggest barriers to treatment was that people did not realize they had a problem and needed help, so informing the community on how to identify a need might inspire treatment seeking. Participants recommended creating educational campaigns to inform community members about mental health and substance use disorders, symptoms, and that recovery is possible. In addition, many mentioned that awareness campaigns should include concrete information about where and how to seek help, as community members might not know where to go, even if they were ready to get care.

[Our community needs] education and encouragement. Knowing that—I think there are a lot of people who don’t think they have a problem, even though they really do. They just find their socioeconomic situation and going to jail a normal thing (42-year-old white man).

Environmental Change

Several participants, especially those familiar with the challenges of reservation life, identified the importance of addressing underlying systemic issues that might contribute to behavioral health conditions. Participants indicated that interventions were needed to challenge the assumption that behavioral health conditions were just part of life and to create opportunities to address the perceived lack of opportunity and upward mobility in these communities. A 27-year-old white man articulated that true change would come with upstream interventions: “It’s a stop gap measure [to] help the ones that you can help now. But then you have to be more forward thinking, how do we prevent the need...how do we foster an environment where kids grow up without those tendencies in their lives?” Changing the community environment and creating employment opportunities was viewed as a way to prevent development of these conditions and to reduce relapse.

I feel that if we had things that would be supportive of a healthy lifestyle—because when people go to treatment they come from that environment back into the old environment, and if there’s nothing there for support, you’re going to go right back in with your friends, whatever. If there was a support system that helped a person to continue to get outpatient treatment, help them get a job, if they needed some life skills to have that education there for them [this would help] (63-year-old AI woman).

Discussion

Despite positive screens on standard mental health and substance use assessments, more than half of the participants in the SDHS reported no perceived need for treatment (63.8% of those with mental health conditions; 98.1% with substance use needs). We explored this discrepancy in this study and found that these differences in actual and perceived need are likely related to how mental health conditions, alcohol, and drug abuse are defined by participants. The generational gap in interpreting mental health conditions presents a promising opportunity to continue to promote treatment seeking among the next generation of rural residents. Findings on alcohol suggest that there is a significant need to begin to reshape community definitions of abuse. Excessive consumption of alcohol was seen as relatively normative by participants, beginning at an early age and not problematic unless it led to harm of others, neglecting responsibility, or legal infractions.

Although family, friends, media, and court mandated treatment could help individuals become aware of their need, the notion that these disorders are a result of weakness and are addressable without seeking help, through sheer willpower, was a common theme. This notion likely impedes treatment, as respondents indicated that formal treatment was unnecessary because sobriety could be achieved independently. Male and female participants noted that maintaining sobriety or seeking care for mental health conditions was often the result of an individual’s commitment or drive, frequently related to a substantial life event, such as having a child. However, our findings offer considerations for reducing disparities in treatment for rural and AI populations that are a necessary complement to addressing traditional access issues. More prominent than access issues were treatment barriers related to denial and stigma around mental health and substance abuse problems; merely increasing the number of facilities and providers and working on quality improvements will not encourage those who do not perceive a need or who think such disorders are a normal part of life to seek care.

Participant narratives around perceived treatment gaps demonstrate that in addition to improving access to care and quality of mental health and substance abuse treatment, community-level interventions should be used to: (1) educate the population about behavioral health conditions and that treatment is possible; (2) reduce the stigma associated with pursuing care; and (3) create social structures that can aid in prevention and early detection. Our findings suggest that educational campaigns which acknowledge the socioeconomic and structural frameworks that influence health and treatment-seeking behaviors, focus on removing fault from the sufferer, and improve awareness of and access to local treatment options could prove effective for both mental health and substance abuse disorders. Community-level intervention strategies could also help ensure that the treatment options for rural and AI populations are tailored to align with cultural beliefs and/or to address social factors, such as adverse childhood events, which have been linked to the development of behavioral conditions in later life.32

There are important limitations to this study. Though the sample was designed to be representative, participants were limited to the state of South Dakota, and findings may not generalize to other rural states, reservations, or more urban settings. It is also possible that bias was introduced because participants self-elected to participate in a follow-up study, and interviews were done by telephone, thereby excluding participants who might lack the economic resources to afford access to a telephone. Additionally, despite multiple attempts, we were unable to reach participants in certain sample categories, such as those who reported using drugs and/or getting all needed treatment for substance use. This may be in part because only 4 individuals (2.3%) who screened positive for substance use and were willing to participate in additional studies perceived a need for treatment. Given what we learned about stigma, it is also possible that participants underreported or withheld relevant information regarding their own experiences with mental health and substance abuse disorders.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide important insight into how mental health, alcohol, and drug use are viewed in rural and reservation communities. Developing interventions that can address the discordance between positive clinical screens and perceived need and that build on tipping points for accessing care may improve gaps in treatment seeking in rural and AI populations. Simply adding additional facilities may not be enough to engage these populations in behavioral health care. Enhancing access to care and improving community-based interventions are important components of future work in this area.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

The authors would like to acknowledge Thomas Meath and Grace Li for expert assistance on discordance and sampling, respectively, and Kristin Chatfield and Sarah Tran for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Funding: This study was funded by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust Grant No. 2014PG-RHC003.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web site.

Appendix A. South Dakota Health Survey: Qualitative Follow-Up

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Wang PS. The descriptive epidemiology ofcommonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29(1):115–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB,Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meit M, Knudson A, Gilbert T, et al. The 2014 update ofthe rural-urban chartbook. Rural Health Reform Policy Research Center; 2014. Available at: http://ruralhealth.und.edu/projects/health-reform-policy-researchcenter/pdf/2014-rural-urban-chartbook-update.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duran B, Oetzel J, Lucero J, et al. Obstacles for rural American Indians seeking alcohol, drug, or mental health treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(5):819–829. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gone JP, Trimble JE. American Indian and Alaska native mental health: diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8(1):131–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rost K, Adams S, Xu S, Dong F. Rural-urban differencesin hospitalization rates of primary care patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(4):503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziller EC, Anderson NJ, Coburn AF. Access to rural mental health services: service use and out-of-pocket costs. J Rural Health. 2010;26(3):214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borders TF, Booth BM. Research on rural residence andaccess to drug abuse services: where are we and where do we go? J Rural Health. 2007;23(s1):79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simmons LA, Havens JR. Comorbid substance and mental disorders among rural Americans: results from the national comorbidity survey. J Affect Disord. 2007;99(1–3):265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, Mitchell CM. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(1):99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The NSDUH Report: Need for and Receipt of Substance Use Treatment among American Indians or Alaska Natives. 2012. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH120/NSDUH120/SR120-treatment-need-AIAN.htm. Accessed February 25, 2015.

- 12.Manson SM. Mental health services for American Indiansand Alaska natives: need, use, and barriers to effective care. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45(7):617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rost K, Fortney J, Fischer E, Smith J. Use, quality, andoutcomes of care for mental health: the rural perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59(3):231–265. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortney J, Rost K, Zhang M, Warren JM. The impact ofgeographic accessibility on the intensity and quality of depression treatment. Med Care. 1999;37(9):884–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rost K, Fortney J, Zhang M, Smith J, Smith GRS Ir..Treatment of depression in Rural Arkansas: policy implications for improving care. J Rural Health. 1999; 15(3):308–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biola H, Pathman DE. Are there enough doctors in myrural community? Perceptions of the local physician supply. J Rural Health. 2009;25(2):115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyt DR, Conger RD, Valde JG, Weihs K. Psychologicaldistress and help seeking in Rural America. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25(4):449–470. doi: 10.1023/A:1024655521619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heflinger CA, Christens B. Rural behavioral healthservices for children and adolescents: an ecological and community psychology analysis. J Community Psychol. 2006;34(4):379–400. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Draus P, Carlson RG. Down on main street: drugs and thesmall-town vortex. Health Place. 2009;15(1):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox JC, Blank M, Rovnyak VG, Barnett RY. Barriers to help seeking for mental disorders in a rural impoverished population. Community Ment Health J. 2001;37(5):421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis M, Spurlock M, Dulacki K, et al. The South Dakotahealth survey: assessing disparities in behavioral health services in rural and reservation areas. J Rural Health. 2015; Published online October 30, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. State Fact Sheets: South Dakota. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/state-fact-sheets/. Accessed February 25, 2015.

- 23.United States Census Bureau. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics. 2010; South Dakota. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed February 25, 2015.

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J, Lowe B. An ultra-brief-screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD scren (PC–PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry. 2004;9(1):9–14. doi: 10.1185/135525703125002360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bush KR, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA, Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.University of Washington Rural Health Research Center. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-codes.php. Accessed May 1, 2014.

- 28.University of North Dakota Center for Rural Health.Rural-Urban Commuting Areas Version 3.10. Available at: http://ruralhealth.und.edu/ruca. Accessed May 1, 2014.

- 29.Hsieh H-F. Three approaches to qualitative content-analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative-research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):331–339. doi: 10.1370/afm.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry In Crabtree BF,Miller BF, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.