Abstract

Allergic asthma is mediated by Th2 responses to inhaled allergens. Although previous experiments indicated that Notch signaling activates expression of the key Th2 transcription factor Gata3, it remains controversial how Notch promotes allergic airway inflammation. Here we show that T cell–specific Notch deficiency in mice prevented house dust mite–driven eosinophilic airway inflammation and significantly reduced Th2 cytokine production, serum IgE levels, and airway hyperreactivity. However, transgenic Gata3 overexpression in Notch-deficient T cells only partially rescued this phenotype. We found that Notch signaling was not required for T cell proliferation or Th2 polarization. Instead, Notch-deficient in vitro–polarized Th2 cells showed reduced accumulation in the lungs upon in vivo transfer and allergen challenge, as Notch-deficient Th2 cells were retained in the lung-draining lymph nodes. Transcriptome analyses and sequential adoptive transfer experiments revealed that while Notch-deficient lymph node Th2 cells established competence for lung migration, they failed to upregulate sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) and its critical upstream transcriptional activator Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2). As this KLF2/S1PR1 axis represents the essential cell-intrinsic regulator of T cell lymph node egress, we conclude that the druggable Notch signaling pathway licenses the Th2 response in allergic airway inflammation via promoting lymph node egress.

Keywords: Immunology, Pulmonology

Keywords: Allergy, Asthma, Signal transduction

Introduction

Allergic asthma is a common but heterogeneous chronic inflammatory lung disease characterized by type 2 airway inflammation and bronchial hyperreactivity (1). Asthma patients experience symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, which are induced by various allergens including house dust mite, fungal spores, pollen, and animal dander. While many asthma patients respond well to standard treatment with inhaled glucocorticoids and β2-agonists, a significant fraction of patients does not achieve disease control using these agents, resulting in high morbidity and symptom burden.

Upon allergen exposure, barrier epithelial cells in the lungs of susceptible individuals mount a proinflammatory response involving the secretion of chemokines, cytokines, and alarmins that induce activation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells and dendritic cells to mount a T helper 2–mediated (Th2-mediated) immune response (2, 3). Disease hallmarks of allergic asthma can be attributed to cytokines that are produced by Th2 cells: IL-4 induces IgE class switching of B cells, IL-5 recruits eosinophils, and IL-13 provokes smooth muscle hyperreactivity, goblet cell hyperplasia, and mucus production (4). It is thought that IL-4 signaling via STAT6 is the main driver of Th2 cell differentiation via enhancement of the expression of the key Th2 transcription factor Gata3 (refs. 5, 6, and reviewed in ref. 7). However, Gata3 and IL-4 can also be induced by Notch signaling, given the capacity of the downstream Notch effector recombination signal–binding protein for immunoglobulin κ J region (RBPJκ) to bind to the upstream Gata3 promoter and a 3′ enhancer element of the Il4 gene (8–12).

The Notch signaling cascade is an important evolutionarily conserved pathway critically involved in cell-cell communication and was originally identified as a pleiotropic regulator of cell fate during embryonic and adult life (reviewed in ref. 13). The function of the Notch pathway is highly context-dependent, as is illustrated by its crucial role at several stages of lymphocyte development, including the B/T cell, αβ/γδ T cell, and CD4+/CD8+ T cell lineage choices (14–16). Because aberrant activity of the Notch pathway has been implicated in various malignancies, it represents an important target for cancer therapy (13). In mature peripheral CD4+ T cells, Notch signaling is critical for Th2 responses, as was shown in mice deficient for RBPJκ or both the Notch1 and Notch2 receptors as well as in mice expressing a dominant-negative form of the essential RBPJκ coactivator mastermind-like (MAML) (8, 10, 11, 17). Absence of Gata3 turned Notch from a Th2 inducer into a potent driver of Th1 differentiation (10, 11). Pharmacological inhibition of Notch signaling using γ-secretase inhibitors or the cell-permeable stapled peptide SAHM1 led to decreased Th2 cytokine production in allergic asthma or food allergy models (18–20). We recently found that surface expression of NOTCH1 and NOTCH2 on both circulating memory CD4+ T cells and Th2 cells is increased in patients with asthma compared with healthy controls (21). Hereby, NOTCH1+ memory CD4+ T cells displayed a more activated phenotype — characterized by increased expression of CD25/IL-2R and the prostaglandin DP2 receptor CRTH2 — than their NOTCH– counterparts (21).

Several studies provided evidence that the Notch ligands Jagged and Delta-like ligand (DLL) instruct Th2 and Th1 cell differentiation, respectively (8, 9). In contrast, an “unbiased amplifier” model was proposed in which Notch ligands are not instructive but rather function to generally amplify Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell responses by enhancing proliferation, cytokine production, and survival (22, 23). Accordingly, we and others found that blocking Notch signaling only during the challenge phase of allergen exposure — and not during sensitization — led to decreased features of allergic airway inflammation (AAI) (18, 20). These findings support a role for Notch signaling in optimizing immune responses rather than inducing initial Th2 cell differentiation. Hence, the precise function of Notch signaling during Th2 cell differentiation and activation in vivo, especially in the context of allergic inflammatory disease, remains controversial.

Here, we used a combination of flow cytometry, histology, and transcriptome analyses of transgenic mice to dissect the role of Notch signals in T cells in acute and chronic models of house dust mite–driven (HDM-driven) AAI. These experiments revealed that a lack of Notch1/Notch2 expression on T cells prevents AAI, which could be only partially rescued by enforced Gata3 expression. Although Notch signaling was not required for Th2 differentiation or proliferation, the absence of Notch signals caused lymph node retention and impaired lung migration of Th2 cells, uncovering a role for Notch signals in the control of Th cell trafficking that explains how Notch signaling licenses AAI.

Results

Notch1 and Notch2 expression on CD4+ T cells is required for the induction of AAI.

We crossed Notch1fl/fl and Notch2fl/fl mice, in which critical exons are flanked by loxP sites (14, 24), with CD4-Cre transgenic mice to delete Notch1 and Notch2 specifically in T cells. Consistent with published findings (25), T cell development in thymus and spleen from CD4-Cre transgenic Notch1fl/fl Notch2fl/fl mice was not affected (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI128310DS1).

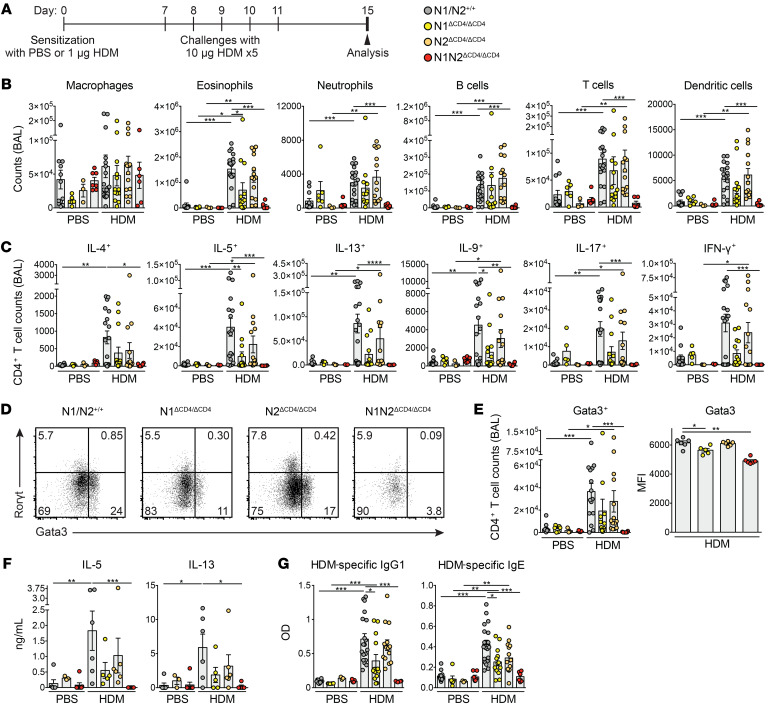

We induced AAI in Notch1 and Notch2 single-deficient (N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4 or N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4) and double-deficient (N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4) mice and WT littermates through sensitization and multiple challenges with HDM (Figure 1A). In these experiments, we included control groups of mice that were equally challenged with HDM, but that were sensitized with PBS. Analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of WT mice 4 days after the last HDM challenge showed significantly increased absolute numbers of eosinophils, B cells, CD4+ T cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) in HDM-sensitized mice compared with PBS-sensitized mice (Figure 1B). N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice developed a milder form of AAI characterized by reduced eosinophilia, while HDM-sensitized N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice displayed an AAI similar to that of WT mice. Strikingly, BAL fluid from HDM-sensitized N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice did not show any increase in immune cell numbers (Figure 1B). The HDM-mediated increase in the total numbers of IL-4+, IL-5+, IL-13+, IL-9+, IL-17+, and IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells observed in WT animals was completely abolished in BAL fluid (Figure 1C) and lungs (data not shown) of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice. Accordingly, Gata3 induction was severely impaired in CD4+ T cells in the BAL fluid (Figure 1, D and E) and lungs (data not shown) from N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice. Total numbers of RORγ+ Th17 and FoxP3+CD25+ Tregs were also reduced in the BAL fluid of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice compared with the other 3 groups of mice (Supplemental Figure 1C). HDM-restimulated mediastinal lymph node (MedLN) cells from N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice showed severely reduced production of IL-5 and IL-13 (Figure 1F). We found reduced levels of HDM-specific as well as total IgG1 and IgE in the serum of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice compared with WT controls (Figure 1G and Supplemental Figure 1D). In these experiments, we noticed redundancy for Notch1 and Notch2, whereby Notch1 appeared dominant (Figure 1, B–G).

Figure 1. Notch1/2 expression on CD4+ T cells is required for AAI induction.

(A) Acute HDM-driven AAI induction protocol. (B) Numbers of FSChiSSChi+CD11c+Siglec-F+ autofluorescent macrophages, FSCintSSChiSiglec-F+ eosinophils, Ly-6G+ neutrophils, CD19+ B cells, CD3+CD4+ T cells, and CD11c+MHCIIhi DCs in BAL fluid of PBS- or HDM-sensitized mice. (C) Intracellular flow cytometry quantification of the numbers of CD3+CD4+ T cells in BAL fluid expressing the indicated cytokines. (D and E) Flow cytometric RORγt/Gata3 profile in CD3+CD4+ T cells in BAL from HDM-treated mice (D) and quantification of Gata3+ cell numbers (left) and Gata3 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in Gata3+ T cells (right) (E). (F) Cytokine production in vitro by HDM-restimulated MedLN cells, measured by ELISA. (G) HDM-specific IgG1 and IgE levels in serum, determined by ELISA. Data are shown as individual values from 3–16 mice per group, together with the mean ± SEM, and are combined from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test.

Follicular T helper (Tfh) cells promote type 2 immunity and have been postulated as precursors of HDM-specific Th2 cells (26, 27). Moreover, Tfh responses rely on Notch signaling (28, 29). Indeed, we observed fewer PD-1+CXCR5+ Tfh cells in the MedLNs of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice as compared with WT controls (Supplemental Figure 1E). To directly assess the importance of a Tfh response for HDM-driven AAI, we genetically deleted the Notch ligand DLL4 on CCL19+ lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells, which prevents the accumulation of Tfh cells in the MedLNs (ref. 28 and Supplemental Figure 2, A–C). Failure to induce Tfh cells indeed blunted IgE induction (for total serum IgE see Supplemental Figure 2D; HDM-specific IgE was detected in the serum of 6 of 7 WT mice but only 2 of 7 DLL4ΔCCL19/ΔCCL19 animals). Strikingly, we still observed full-blown eosinophilia in Tfh-deficient DLL4ΔCCL19/ΔCCL19 mice and even higher numbers of Th2 cells in the BAL fluid than in WT littermates (Supplemental Figure 2, E and F). Therefore, the role of Notch signals in Tfh formation does not provide an explanation for our finding that eosinophilic HDM-driven AAI is reduced in the absence of Notch on T cells.

Together, these findings show that the induction of HDM-driven AAI is moderately reduced in N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice, apparently normal in N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice, and abrogated in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice.

Notch signaling in CD4+ T cells is required for airway remodeling and hyperreactivity.

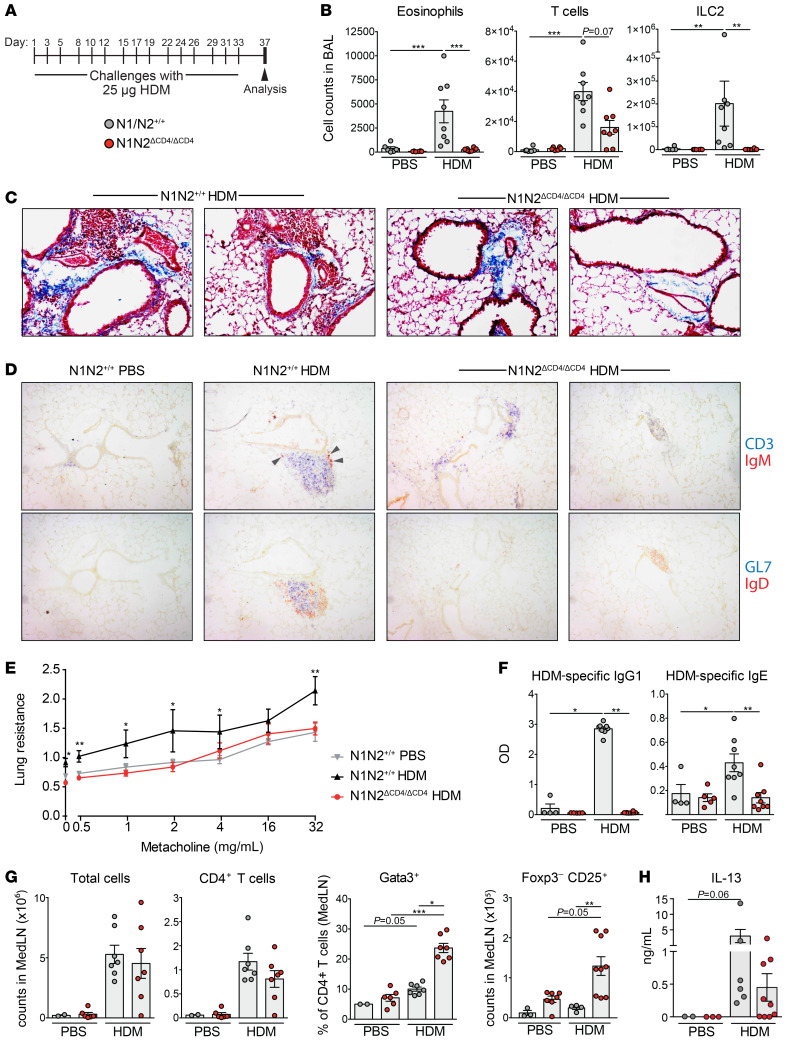

To investigate whether Notch signaling is required for AAI-associated airway remodeling and hyperreactivity, we subjected N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 and WT mice to a chronic HDM-induced asthma model in which mice were challenged with HDM for 5 consecutive weeks (Figure 2A). In line with our findings in the acute AAI model, we found reduced inflammation in BAL fluid of HDM-challenged N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice as compared with WT controls (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the frequency of CD69+ tissue-resident memory CD4+ T cells in the lung was not affected by the absence of Notch signaling (Supplemental Figure 3, A and B), although Th2 cytokine–expressing CD4+ T cells were reduced in the lung and virtually absent in BAL fluid (Supplemental Figure 3, C and D).

Figure 2. Notch signaling in CD4+ T cells is required for airway remodeling and hyperreactivity.

(A) Chronic HDM-driven AAI induction protocol. (B) Numbers of FSCintSSChiSiglec-F+ eosinophils, CD3+ T cells, and Lineage–Sca-1+T1ST2+ group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) in BAL fluid from PBS- or HDM-treated mice. (C) Histological Masson’s trichrome staining on lung tissue from WT (2 examples, left) and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 (2 examples, right) mice. Blue staining indicates the presence of connective tissue, nuclei are stained in dark red, and cytoplasm is pink. Original magnification, ×100. (D) Consecutive slides from lung tissue of the indicated mice, showing the presence of CD3+ T cells (blue) and IgM+ plasma cells (brown, arrows, top row); and GL7+ GC B cells (blue) and IgD+ B cells (brown, bottom row). Only in HDM-exposed WT mice were iBALT structures containing B cells, T cells, GL7+ GC B cells, and IgM+ plasma cells detected. Original magnification, ×100. (E) Airway hyperresponsiveness as measured by lung resistance upon increasing doses of inhaled methacholine in PBS- or HDM-treated mice. (F) HDM-specific IgG1 and IgE levels in serum, determined by ELISA. (G) Numbers of total cells, CD3+CD4+ T cells, Gata3+CD3+CD4+ Th2 cells, and FoxP3–CD25+ activated CD3+CD4+ T cells in MedLNs of PBS- or HDM-treated mice. (H) IL-13 production in vitro by HDM-restimulated MedLN cells, measured by ELISA. Data are shown as individual values from 6–8 mice per group, together with the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test.

The presence of HDM-induced cellular infiltrates and collagen deposition in the lungs was reduced in HDM-treated N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2C). In this chronic AAI model (30), inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) structures were formed that contained both T and B cells, including GL7+ germinal center (GC) B cells (Figure 2D). By contrast, in the lungs of HDM-exposed N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice, most T cells were not iBALT-associated, and iBALT structures were less abundant, smaller in size, and negative for GL7+ GC B cells (Figure 2D). IgM plasma cells were readily detectable in or close to the iBALT structures in WT mice, but not in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 animals (Figure 2D).

Airway hyperreactivity, measured by resistance to methacholine, was significantly lower in HDM-treated N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice than in WT mice (Figure 2E). Likewise, both total and HDM-specific IgG1 and IgE serum levels were strongly decreased in HDM-challenged N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice (Figure 2F and Supplemental Figure 3E). The lack of IgE response in this chronic AAI model cannot be readily explained by a GC defect, since N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice displayed normal numbers of GL7+CD95+ GC B cells and Tfh cells in the MedLNs, in contrast to our findings in the acute HDM-driven AAI model (compare Supplemental Figure 3, F and G, with Supplemental Figure 1E).

In the acute AAI model (Figure 1A), both PBS- and HDM-sensitized mice were challenged with HDM, resulting in an equally high MedLN cellularity in both groups (data not shown). In the chronic AAI model, however, we compared HDM-challenged mice with mice that had received only PBS for 5 weeks, so we could evaluate the induction of T cell expansion and activation in the MedLNs. Despite the strongly reduced AAI in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice, we observed a robust HDM-driven increase in MedLN cellularity and CD4+ T cell counts. Strikingly, Gata3+ Th2 cells and activated CD25+FoxP3–CD4+ T cells were particularly abundant in the MedLNs of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice (Figure 2G). In vitro HDM-restimulated MedLN cultures from N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice produced IL-13, although cytokine levels appeared lower than in cultures from WT mice (Figure 2H).

In summary, upon chronic HDM exposure, Notch signaling in CD4+ T cells is required for the induction of AAI, tissue remodeling, and bronchial hyperreactivity in the lung. However, in the chronic HDM-driven AAI model, Notch signaling does not appear to be critical for activation of naive T cells and Th2 polarization in the MedLNs, but does appear to be critical for aspects of memory Th2 cell function, such as the maintenance of these cells’ Th2 identity or their migration to the lungs.

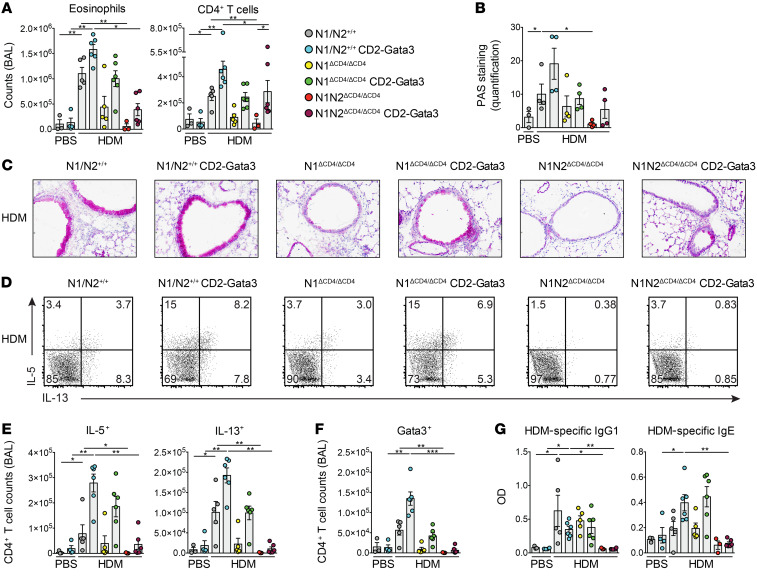

Enforced Gata3 expression only partially rescues AAI induction in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice.

Because Gata3 is crucial for Th2 cell identity and is a direct Notch target (8), we investigated whether enforced Gata3 expression could rescue AAI induction in the absence of Notch signaling. We used transgenic CD2-Gata3 mice, which constitutively express Gata3 in all T cell subsets under the control of the human CD2 promoter and show increased AAI susceptibility (31, 32). We investigated CD2-Gata3 transgenic and nontransgenic littermates that were N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4, N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4, or WT in our acute HDM-driven AAI model. Whereas enforced Gata3 expression increased the numbers of various inflammatory cells in BAL fluid of all 3 groups upon HDM exposure, eosinophilia was only partially rescued in CD2-Gata3 N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 4A). Similarly, mucus hyperproduction by goblet cells (as quantified by histological periodic acid-Schiff staining) was only partially rescued in CD2-Gata3 N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4 and CD2-Gata3 N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice compared with nontransgenic littermates (Figure 3, B and C). Importantly, enforced Gata3 expression increased the numbers of IL-5+, IL-13+, and Gata3+ CD4+ T cells in BAL fluid of WT and N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice, but did not induce any recovery of cytokine-producing Th2 cells in the BAL fluid of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice (Figure 3, D–F, and Supplemental Figure 4B). In contrast, IL-9+ CD4+ T cell, RORγ+ Th17 cell, and FoxP3+CD25+ Treg numbers were rescued in BAL fluid of CD2-Gata3–transgenic N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice (Supplemental Figure 4B). IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells were unaffected, as expected. Enforced Gata3 expression did not affect HDM-specific or total serum IgG1 levels. However, transgenic Gata3 enhanced the induction of both HDM-specific and total serum IgE in WT and N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice, but not in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice (Figure 3G and Supplemental Figure 4C). Finally, we also observed that enforced Gata3 expression in mice with a T cell–specific deficiency of RBPJκ did not rescue hallmarks of the Th2 response, including induction of eosinophilia and IL-4+, IL-5+, and IL-13+ Th cells in BAL fluid as well as serum IgE (Supplemental Figure 4, D–F).

Figure 3. Limited rescue of the Notch-deficient AAI phenotype by enforced Gata3 expression.

(A) Numbers of eosinophils and CD3+CD4+ T cells in BAL fluid of the indicated mice sensitized with PBS or HDM (according to the scheme in Figure 1A). (B and C) Quantification of mucus production from periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of lung tissue sections (B) and representative examples (C) from the indicated HDM-treated mice. Original magnification, ×100. (D and E) Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of cytokine production by CD3+CD4+ T cells in BAL fluid from the indicated HDM-treated mice (D), quantified in E. (F) Quantification of Gata3+CD3+CD4+ T cells in BAL fluid. (G) HDM-specific IgG1 and IgE levels in serum, determined by ELISA. Data are shown as individual values from 3–6 mice per group, together with the mean ± SEM, and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test.

In summary, although enforced Gata3 expression largely rescued AAI induction in N1ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice, it had limited effects in mice with T cells lacking both Notch1 and Notch2 or RBPJκ. These findings indicate that in type 2 responses, Notch has additional critical functions in CD4+ T cell biology beyond Gata3 induction.

Notch signals are not required for activation, proliferation, and Th2 differentiation of CD4+ T cells.

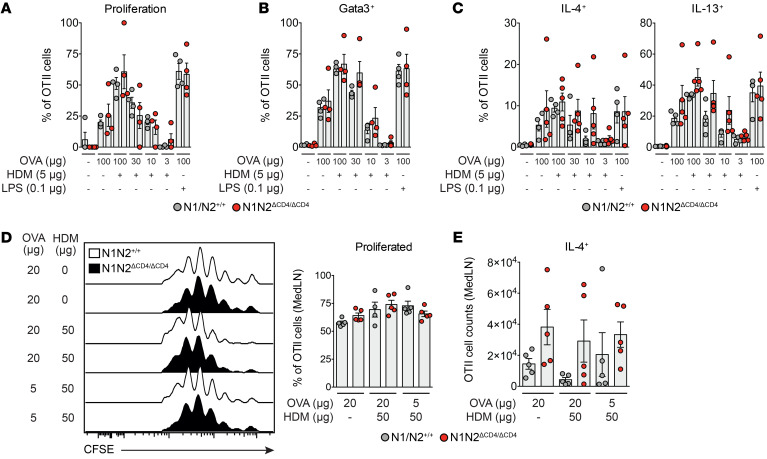

To further explore the capacity of Notch-deficient CD4+ T cells to differentiate into the Th2 lineage, we crossed N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice with OTII transgenic mice expressing a chicken ovalbumin-specific (OVA-specific) T cell receptor (TCR) on CD4+ T cells. Purified CFSE-labeled naive CD4+ T cells from OTII WT and OTII N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice were cocultured with bone marrow–derived GM-CSF DCs (maturated with HDM or LPS and loaded with a range of OVA concentrations). A lack of Notch signaling in the OTII CD4+ T cells did not hamper their proliferation or activation (as indicated by surface CD44 expression) (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure 5A). Moreover, induction of Gata3 and the capacity to produce IL-4 or IL-13 were not affected (Figure 4, B and C). Rather, a modest increase in Gata3 expression and cytokine production was noticed, particularly at lower antigen concentrations. Likewise, in vitro activation and polarization of purified naive T cells from RBPJκΔCD4/ΔCD4 and WT mice using anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies in combination with various cytokines and anti-cytokine antibody cocktails (33) did not affect cellular expansion or Th subset differentiation (Supplemental Figure 5, B–E).

Figure 4. Notch is not required for CD4+ T cell activation, Th2 differentiation, and proliferation.

(A–C) Proportions of proliferating cells as determined by CFSE dilution (A), and Gata3+ cells (B) and cytokine-expressing cells (C) measured by intracellular flow cytometry of cultured splenic OTII CD4+ T cells from WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice upon in vitro activation with the indicated stimuli. (D and E) Flow cytometric analysis (left) and quantification (right) of proliferation measured by CFSE dilution (D) and total numbers of IL-4+ WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII CD4+ T cells (E) in MedLNs after in vivo transfer into mice subsequently challenged with the indicated concentrations of OVA and HDM. Data are shown as individual values from 4–5 mice per group, together with the mean ± SEM. Differences between WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice were tested for statistical significance using a Kruskal-Wallis test.

Notch signaling was reported to potentiate PI3K-dependent signaling downstream of the TCR and CD28 through activation of Akt kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (34–36). Notch could in this way enhance T cell effector function and survival, enabling T cells to respond to lower antigen doses. However, we did not detect any defect in the phosphorylation of the S6 ribosomal protein, a downstream target of Akt, in splenic T cells from N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice stimulated for 3 hours with a range of anti-CD3/CD28 antibody concentrations (Supplemental Figure 5F).

Next, we investigated whether Notch signaling is required for activation of naive T cells in vivo. CFSE-labeled OTII T cells from N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 and WT mice were injected intravenously into WT recipients. One day later, mice were challenged intranasally with OVA and/or HDM. Three days after challenge, N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 and WT OTII T cells from MedLNs showed similar in vivo proliferation or capacity to produce IL-4 (Figure 4, D and E).

We conclude from these in vitro and in vivo experiments that Notch signaling is not critically involved in the expansion, activation, or Th2 polarization of naive CD4+ T cells upon TCR stimulation.

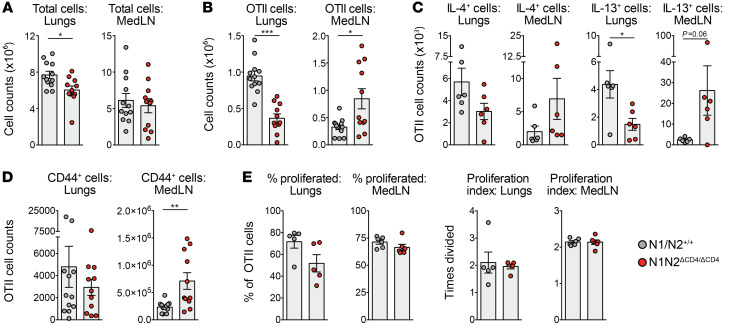

Notch signaling promotes lymph node egress of in vitro–polarized Th2 cells.

To explore the role of Notch in established Th2 cells, we transferred in vitro–polarized WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII CD4+ T cells intravenously into WT recipient mice that were subsequently challenged with OVA and HDM for 4 consecutive days. On day 5, mice that received N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 Th2 cells had similar total cell counts in MedLNs but a significantly reduced cellular influx into the lungs compared with mice that received WT Th2 cells (Figure 5A). Importantly, mice that received N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII CD4+ T cells had lower numbers of these cells in lungs, but significantly higher numbers in MedLNs (Figure 5B). Notch-deficient OTII CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 and particularly IL-13 were reduced in the lungs, while proportions and absolute numbers of IL-4+ or IL-13+ cells in the MedLNs were higher for N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 than for WT OTII CD4+ T cells (Figure 5C and Supplemental Figure 5G). Moreover, substantially more N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 than WT OTII cells in the MedLN were positive for the CD44 memory marker, while proliferation rates were unaffected by Notch signals (Figure 5, D and E).

Figure 5. Notch signaling controls cellular trafficking of in vitro–polarized Th2 cells.

(A–D) Numbers of total (A) and OTII CD4+ T cells (B) as well as cytokine-positive (C) or CD44+ (D) OTII CD4+ T cells in lungs and MedLNs in mice treated with HDM and OVA after in vivo transfer of in vitro–Th2-polarized WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII CD4+ splenic T cells. (E) Proportions of proliferating cells (left) and proliferation index (right) of transferred Th2-polarized OTII CD4+ T cells as determined by CFSE dilution. Data are shown as individual values from 5–12 mice per group (A, B, and D) or 6 mice per group (C and E), together with the mean ± SEM, and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by Mann-Whitney U test.

Taken together, these findings support a role for Notch signaling in promoting the migration of memory Th2 cells from the lymph node into the lungs in the context of AAI.

Notch signals control a cytokine signaling gene expression program in Th2 cells in vivo.

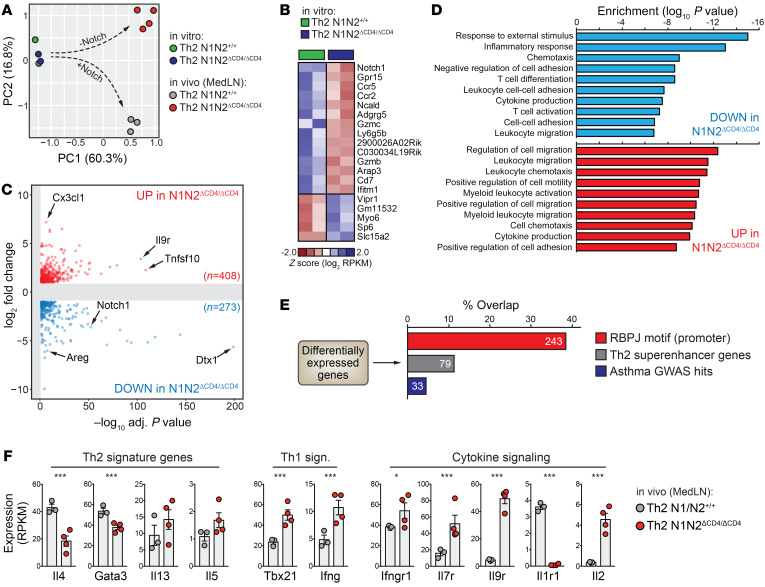

Next, we used RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) to compare the transcriptomes of WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII Th2 cells directly after in vitro polarization and 5 days after in vivo transfer and OVA/HDM treatment. RNA-Seq confirmed defective expression of Notch1 and Notch2 in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII Th2 cells (Supplemental Figure 6A). Principal component analysis (PCA) and unbiased hierarchical clustering of gene expression values revealed a negligible impact of Notch deficiency in vitro, while the transcriptomes of in vivo–transferred WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII Th2 cells isolated from MedLNs diverged substantially (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure 6B), demonstrating that changes resulting from Notch deficiency arose following allergen challenge in vivo. While only 19 differentially expressed (DE) genes (defined as 2-fold upregulated or downregulated, adjusted P < 0.05) were detected after in vitro polarization, 681 genes differed between WT and N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII Th2 cells in the MedLNs (Figure 6, B and C; Supplemental Figure 6, C and D; and Supplemental Table 2). Pathway enrichment analyses of these 681 DE genes revealed a strong overrepresentation of genes involved in cytokine/chemokine production and responsiveness, as well as leukocyte chemotaxis and migration (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Transcriptome analyses implicate Notch signaling in Th2 cell cytokine responsiveness and tissue migration.

(A) Principal component analysis (PCA) using RNA-Seq expression values from WT (N1N2+/+) and Notch-deficient (N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4) OTII Th2 cells after in vitro polarization or 5 days after in vivo transfer and OVA/HDM treatment. (B) Heatmap depicting differentially expressed (DE) genes detected after in vitro Th2 polarization of WT and Notch-deficient Th2 cells. (C) Volcano plot showing DE genes between WT and Notch-deficient Th2 cells from MedLNs. (D) Selected pathways associated with DE genes shown in C. (E) Percentage of overlap between DE genes in C and genes with RBPJκ binding motifs in their promoter, previously identified Th2 superenhancer genes, and asthma-associated (by GWAS) genes. (F) Expression levels of selected genes (n = 3–4 biological replicates, shown as individual values, together with the mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; adjusted P values from DESeq2.

As expected, MedLN N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII Th2 cells expressed dramatically reduced levels of the canonical Notch target gene Dtx1 (Supplemental Figure 6, E and F). Many promoters of DE genes harbored RBPJκ DNA-binding motifs (~36%; Figure 6E). While Il4 and Gata3 were reduced, Foxp3 and Rorg expression was unchanged (Figure 6F and Supplemental Figure 6F). Tbx21 (encoding T-bet) and Ifng were upregulated, suggesting diminished Th2 phenotypic stability and increased plasticity toward a Th1 phenotype in the absence of Notch (Figure 6F). Impaired Notch signaling in Th2 cells decreased the expression of genes associated with Th2 superenhancers, which are enriched for lineage-defining Th2 genes including Il4, Satb1, and Maf (ref. 37, Figure 6E, and Supplemental Table 2), as well as genes linked to asthma-associated genetic variants from genome-wide association studies (38), e.g., TLR1, SPP1, and PLCL1 (Figure 6E and Supplemental Table 2).

In summary, we found that Notch signaling regulates a critical part of the in vivo gene expression program that controls lymph node Th2 lineage identity and cytokine signaling.

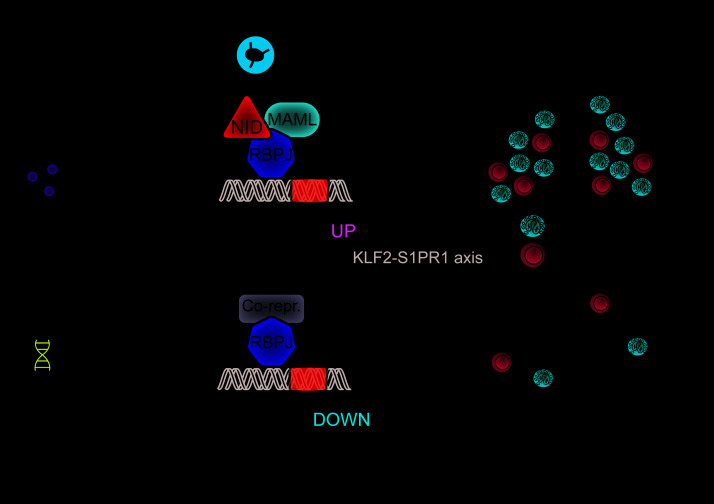

Disruption of the KLF2/S1PR1 axis in Notch-deficient T cells.

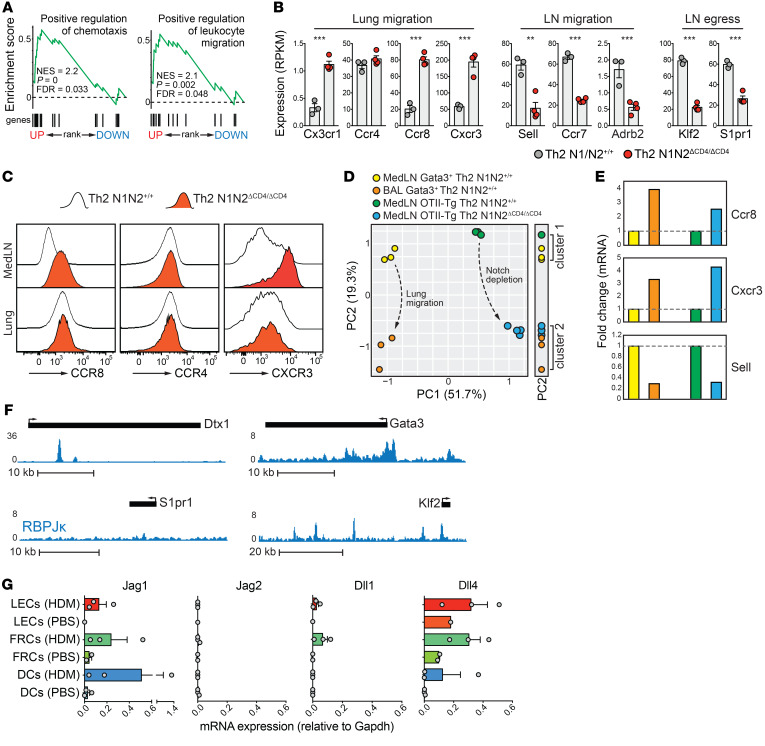

The most striking transcriptional changes in MedLN N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII Th2 cells concerned genes involved in cellular migration and chemotaxis (Figure 7, A and B). Chemokine receptors associated with lung migration, including Ccr8 (39), Cx3cr1 (40), and Cxcr3 (41), were prominently upregulated in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 MedLN Th2 cells. Together with high-level expression of the Th2 lung homing marker Ccr4 (42), this indicated that MedLN Notch-deficient Th2 cells adopted a phenotype that supports lung migration (Figure 7B). Flow cytometry analysis confirmed increased surface expression of CCR8 and CXCR3 on MedLN N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 Th2 cells as compared with WT Th2 cells, reaching levels that were similar to or higher than those observed on lung Th2 cells, respectively (Figure 7C). In support of a functional lung migratory phenotype of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 MedLN OTII Th2 cells, PCA using expression values of the 681 DE genes clustered N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 MedLN Th2 cells together with BAL fluid but not with MedLN WT Gata3+ Th2 cells (PC2, Figure 7D) from mice subjected to the more physiological acute HDM-driven AAI protocol depicted in Figure 1A. Indeed, critical T cell migration genes, Ccr6, Cxcr3, and Sell, showed similar transcriptional changes upon lung migration and when retained in the MedLNs as Notch-deficient cells (Figure 7E).

Figure 7. Notch signals promote Th2 cell lymph node egress via transcriptional activation of the KLF2/S1PR1 axis.

(A) Gene set enrichment analyses using the preranked differentially expressed (DE) genes shown in Figure 6C. (B) Expression levels of selected genes (n = 3–4 biological replicates; error bars denote SEM). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; adjusted P values from DESeq2. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of surface CCR4, CCR8, and CXCR3 expression on WT and Notch-deficient Th2 cells from MedLNs and lungs of mice treated with HDM and OVA. (D) PCA using expression values of the 681 DE genes (Figure 6C) from MedLN WT and Notch-deficient OTII Th2 cells as well as Gata3+ MedLN and BAL Th2 cells from GATIR mice treated with HDM (as in Figure 1A). The 1-dimensional side plot illustrates how PC2 clusters WT with OTII MedLN cells and WT BAL Th2 cells with N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII MedLN Th2 cells. (E) Expression fold changes for indicated genes in Gata3+ Th2 cells from MedLNs versus BAL or WT versus Notch-deficient OTII transgenic MedLN Th2 cells (representative of 3 experiments; color code as in D). (F) RBPJκ ChIP-Seq signal (from the 8946 T-ALL cell line; ref. 51) in the Dtx1 and Gata3 (both canonical Notch target genes) and the S1pr1 and Klf2 loci. (G) Quantitative PCR measurements of Notch ligand genes in populations of CD11b+ migratory DCs, lymphoid endothelial cells (LECs), and fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) from the MedLNs of mice 3 days after PBS or HDM exposure.

Alternative explanations for the lung migratory defect we observed in Notch-deficient Th2 cells are persistent MedLN retention (43) and a failure to actively egress from the MedLNs via sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signaling (44). However, the lymph node retention receptor genes Sell (encoding L-selectin) and Ccr7, as well as Adrb2 encoding the β2-adrenergic receptor that inhibits lymph node egress (45), were downregulated in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 MedLN Th2 cells (Figure 7B). Instead, N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 MedLN Th2 cells exhibited reduced expression of S1pr1 encoding the S1P receptor, the master T cell–intrinsic regulator of effector T cell lymph node egress (46), as well as its critical upstream regulator Klf2 (Krüppel-like factor 2) (47) (Figure 7B). Ecm1, Foxo1, and Cd69, all implicated in regulation of S1PR1 expression (48, 49), were unchanged (Supplemental Figure 6F). Zfp36, a negative regulator of Klf2 in B cells (50), was downregulated. Direct control of Klf2 expression by Notch signaling was further supported by extensive RBPJκ binding of the Klf2 locus (including the promoter region; Figure 7F) in a T cell line (51). Transmigration of S1PR1-expressing T cells into lymphatic sinuses and subsequent egress into efferent lymph are mediated by an S1P gradient across lymphoid endothelial cells (LECs) (52). As it is conceivable that S1PR1 expression in T cells is induced by engagement of Notch receptors on LECs, we used reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) to analyze expression of Notch ligand genes in sorted gp38+CD31+ LECs from WT mice 3 days after treatment with PBS or a single high dose of HDM. In vivo HDM exposure induced transcription of Jag1, Dll1, and Dll4 in LECs at levels that were comparable to those found in gp38+CD31– fibroblastic reticular cells and DCs (Figure 7G).

Our findings strongly support disruption of the KLF2/S1PR1 axis — and not altered CCR7, L-selectin, or β2-adrenergic receptor expression — as the underlying cause of defective Th2 cell lymph node egress. Although Notch-deficient MedLN Th2 cells readily adopt a lung migratory phenotype, impaired MedLN egress prevents efficient lung migration, thus explaining the attenuated allergen-driven AAI in N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 mice.

Lymph node N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 Th2 cells have substantial capacity to migrate into the lungs.

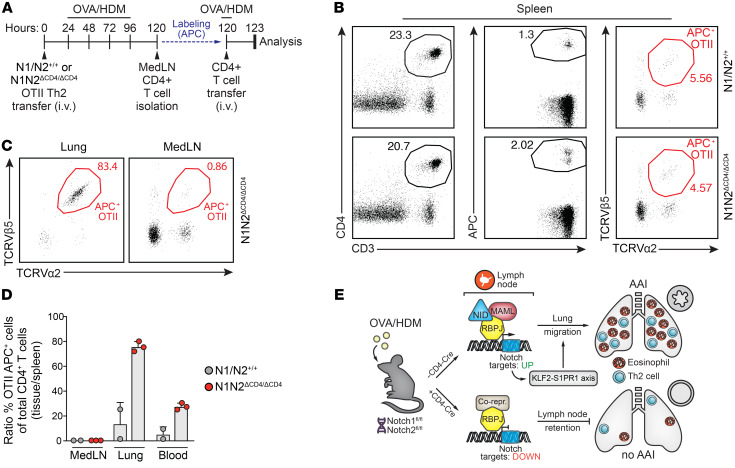

Next, we investigated whether the lung migratory phenotype of MedLN N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 Th2 cells would indeed enable them to home toward the lung after adoptive transfer (and MedLN egress would thus no longer be required). To this end, we first transferred either WT or N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 in vitro–polarized OTII Th2 cells into WT recipient mice, which were subsequently challenged with OVA and HDM for 4 consecutive days (Figure 8A). Total CD4+ T cell fractions were isolated from the MedLNs of these mice, APC-labeled, and adoptively transferred into a second group of WT mice that were treated with OVA and HDM 1 day before transfer (Figure 8A). In these experiments, the numbers of APC-labeled total CD4+ T cells or TCRVβ5+TCRVα2+ OTII T cells that migrated into the spleen were comparable between the 2 groups of mice (Figure 8B). APC-labeled CD4+ T cells could not be retrieved from the lungs of mice that had received CD4+ T cells from MedLNs containing WT OTII Th2 cells. By contrast, in lungs of mice that had received CD4+ T cells from MedLNs containing N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 OTII Th2 cells, a population of APC-labeled CD4+ T cells was present that almost entirely consisted of N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 TCRVβ5+TCRVα2+ OTII T cells (Figure 8C). In these mice, the fraction of APC-labeled CD4+ T cells migrating to the MedLNs largely contained WT non-OTII CD4+ T cells and only very few N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 TCRVβ5+TCRVα2+ OTII T cells. Thus, lymph node–derived Notch-deficient but not WT OTII Th2 cells were biased toward lung migration (Figure 8D).

Figure 8. MedLN-derived N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4 Th2 cells have the capacity to migrate into the lungs after adoptive transfer.

(A) Sequential adoptive transfer protocol: in vitro–polarized OTII T cells (either WT or N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4) were transferred i.v. into primary WT recipient mice, which were subsequently challenged with OVA/HDM for 4 days. Total CD4+ T cell fractions from the MedLNs of these mice were APC-labeled and adoptively transferred into secondary WT recipient mice that were treated intranasally with OVA 1 day before transfer and analyzed after 3 hours. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic cells from secondary recipient mice that received MedLN CD4+ T cells from the indicated mouse genotypes, showing the gating of CD3+CD4+APC+ labeled cells (left) and the TCRVβ5+TCRVα2+ OTII Th2 cells from this population (right). (C) Analysis of TCRVβ5+TCRVα2+ labeled Th2 cells in the lungs (left) or MedLNs (right) of secondary recipient mice. (D) Quantified homing capacities of WT and Notch1/2-deficient OTII T cells after 2 consecutive transfers. Data are shown as a ratio of the percentage TCRVβ5+TCRVα2+APC+ OTII cells of the total CD3+CD4+ T cells in MedLNs, lung, and blood over the equivalent percentage of OTII cells in the spleen. Depicted are individual values from 2–3 biological replicates, together with the mean ± SEM. (E) Model summarizing the role of Notch signaling in controlling Th2 cell trafficking in AAI via activation of the KLF2/S1PR1 axis. In lymph node CD4+ Th2 cells, Notch receptor–ligand interactions induce nuclear translocation of the Notch intracellular domain (NID) that, together with its coactivator MAML and the DNA-binding protein RBPJκ, serves as a transcriptional activator. In Th2 cells that are ready to migrate to the lungs, this Notch complex activates the KLF2/S1PR1 axis to promote lymph node egress. This allows Th2 cells to migrate to the lung and establish eosinophilic AAI.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that Notch signaling is required for upregulation of the KLF2/S1PR1 axis, allowing antigen-activated Th2 cells to leave the lymph node and migrate into the lungs (Figure 8E).

Discussion

The Notch signaling pathway in T cells is essential for type 2 immune responses such as host defense to helminth infection but also allergic inflammation (8). However, it has remained obscure how Notch signaling supports Th2 cell–driven inflammation in vivo and whether Notch acts in an instructive or more unbiased fashion to shape CD4+ T cell fate.

We addressed the contested role of Notch signaling using a physiologically relevant HDM-driven mouse model of AAI. While the Notch1/2 receptors were indispensable for induction of eosinophilia, Th2 cell accumulation in the lungs, airway remodeling, and HDM-specific IgE, rescue of these hallmarks of AAI by Gata3 overexpression was surprisingly limited. Notch signaling therefore controls critical aspects of Th2-mediated AAI beyond direct transcriptional activation of Gata3. We found that Notch1/2 or RBPJκ was not required for T cell activation, proliferation, and Th2 polarization, either induced in vitro by anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation or antigen-loaded GM-CSF bone marrow–derived DCs, or induced in vivo through antigenic stimulation of transferred OVA-specific CD4+ T cells. Moreover, when in vitro–differentiated OVA-specific Notch1/2-deficient Th2 cells were transferred into mice and activated by OVA, these cells showed apparently normal proliferation and Th2 cytokine production. Instead, Notch1/2-deficient Th2 cells displayed defective lung trafficking and accumulated in lung-draining lymph nodes. These Notch1/2-deficient Th2 cells failed to upregulate the KLF2/S1PR1 axis, the essential mediator of lymph node egress. Nevertheless, their chemokine receptor expression signature enabled them to migrate into the lung, when the need for MedLN egress was removed via sequential adoptive transfer. Therefore, we conclude that Notch signals license the Th2 response in AAI via promoting lymph node egress (Figure 8E).

When T cells encounter antigen presented by activated DCs in the lymph node, KLF2 and S1PR1 expression is downregulated by TCR and IL-2R signaling (44). As a result, T cells are retained in the lymph node, allowing for sufficient time to interact with DCs. Only when polarized, Th2 cells prepare for emigration and upregulate the expression of ECM-1, which leads to inhibition of IL-2R signaling, KLF2/S1PR1 re-expression, and Th2 cell egress (48). It is conceivable that the observed reduced Klf2 and S1pr1 expression in Notch1/2-deficient Th2 cells reflects an early activation arrest in the lymph node before they reach the stage of egress competency. However, several lines of evidence support the alternative explanation that Notch signaling directly activates Klf2 and its target S1pr1. First, ECM-1 expression levels were not affected in Notch-deficient Th2 cells, indicating that the cells do reach the stage of ECM-1 upregulation. Second, RBPJκ binding of the Klf2 promoter region in a T cell line (51) is consistent with direct control of Klf2 expression by Notch signals. Third, despite low S1PR1 expression, Notch-deficient Th2 cells are competent for lung migration, and their transcriptional profile and chemokine receptor expression pattern showed a striking resemblance to those of Th2 cells in the airways. This transcriptomic similarity also makes it unlikely that reduced Klf2 expression or S1PR1 signaling would directly affect chemokine receptor expression in Th2 cells. In this context, it has been demonstrated that even in the absence of retention signals such as CCR7, cell-intrinsic S1PR1 signaling is the overriding factor that regulates effector T cell egress kinetics from draining lymph nodes (46).

Our findings do not support a role for Notch in other pathways that can influence S1PR1 expression, including PI3K/mTOR signaling, CD69-mediated inhibition, or transcriptional regulation via Foxo1. Importantly, our transcriptome analyses indicated no reinforced lymph node retention signals in Notch-deficient effector Th2 cells, because CCR7, L-selectin, and β2-adrenergic receptor expression levels were strongly downregulated. Nevertheless, it is evident that Notch signaling has additional effects, including direct regulation of Il4 and Gata3 gene expression (8). Accordingly, we found that Notch-deficient Th2 cells presented distinct cytokine (receptor) gene expression profiles and hallmarks of lineage instability, including a partial loss of repression of Th1 signature genes.

It is currently unknown which cells in the draining lymph node provide the signals that activate the Notch pathway in differentiated Th2 effector cells to support their egress. Before emigration, antigen-specific effector T cells localize adjacent to both cortical and medullary sinuses in the lymph node periphery, where they exhibit intense probing behavior with lymphatic endothelial cells before entering the sinuses in an S1PR1-dependent fashion (46). Therefore, it is attractive to speculate that endothelial cells are critical to provide Notch ligands, particularly since these cells have the capacity to upregulate Jagged expression in response to inflammatory mediators such as TNF and IL-6 (53, 54). Accordingly, we found that HDM exposure in mice induced Jagged and DLL expression in MedLN endothelial cells (Figure 7G) and that Jagged expression on DCs is not critical for HDM-driven allergic AAI in vivo (55).

It was recently shown in a helminth infection model that the Notch1/2 receptors on T cells are required for Tfh generation and IgE class switching, but largely dispensable for Th2 differentiation and lung eosinophilia (29). These results are in apparent contrast with our findings for AAI, as the absence of Notch signaling in T cells — irrespective of a successful Tfh response in the lymph node — abolished both IgE induction and lung eosinophilia. Directly comparing the 2 models is challenging, because of considerable differences in the immunopathological mechanisms involved. For example, cardinal features of the type 2 immune response, including IL-5/IL-13 production and eosinophilia, are rapidly induced by group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) in the Nippostrongylus brasiliensis model, which in turn support T cell activation (56). In our HDM-driven AAI model, however, ILC2 induction relies on T cell activation (57) and on Notch signaling in T cells (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, our experiments show that in HDM-driven AAI, a vigorous Th2 response is generated in the lung even in DLL4ΔCCL19/ΔCCL19 mice defective for MedLN Tfh responses. These data are in line with our previous findings in Cd40l–/– mice, in which eosinophilic airway inflammation in the chronic HDM-driven model is not hampered despite impaired Tfh cell generation (30). The role of Notch signals in Tfh formation therefore does not provide an explanation for our finding that eosinophilic AAI is reduced in the absence of Notch on T cells. Importantly, taken together the studies show that eosinophilia and lung Th2 responses in both helminth and HDM-driven experimental models appear independent of a Tfh response in draining lymph nodes. Both during helminth infection and in our acute HDM-driven AAI model, the absence of Notch signaling in T cells hampered Tfh formation and IgE induction. During chronic AAI, however, MedLN Tfh formation appeared unaffected even though serum IgE was strongly reduced. This finding may point to an important role for iBALT in IgE induction, paralleling the importance of iBALT for the generation of circulating protective antiviral antibodies upon influenza infection in mice (58).

Altogether, we show that in AAI Notch signaling is required to license the Th2 response via promoting lymph node egress of effector Th2 cells. The current study provides a mechanistic explanation for the previous finding that pharmacological Notch inhibition specifically during the challenge phase reduces AAI and bronchial hyperreactivity in mice (18, 20). Together with our recent observation that circulating T cells from asthma patients exhibit increased Notch expression (21), this further emphasizes that blocking of the Notch signaling pathway may represent an attractive therapeutic strategy to suppress Th2 cell–mediated inflammation in patients with allergic asthma. Given that Notch may act as an unbiased amplifier of T cell responses irrespective of Th cell polarization (22), it is conceivable that Notch signaling controls lymph node egress not only of Th2 cells, but also of other Th subsets in different inflammatory contexts such as respiratory infections or tumor immunosurveillance.

Methods

Mice

WT mice were purchased from Envigo. Notch1fl/fl mice (14), Notch2fl/fl mice (24), and RBPJκfl/fl mice (59) were crossed with CD4-Cre transgenic mice (25), with CD2-Gata3 transgenic mice (32), with OTII mice (60), or with Gata3-YFP reporter (GATIR) mice (38, 61). Dll4/Dll4ΔCcl19/ΔCcl19 mice have previously been described (28). All mice were bred on a C57BL/6 background in the Erasmus MC animal facility under specific pathogen–free conditions and genotyped by PCR as previously described (14, 24, 25, 32, 59). Both male and female 6- to 14-week-old mice were used in experiments. Mice were given ad libitum access to food and water.

Preparation of single-cell suspensions

Directly after harvest, spleen, lymph nodes, thymus, and lungs were mechanically disrupted in a 100-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon). To prepare single-cell suspensions from bone marrow, femurs and tibiae from mice were cleaned with 70% ethanol and mechanically disrupted in RPMI 1640 containing GlutaMAX-I (Thermo Fisher Scientific), after which cells were separated from bones using a cell strainer. Erythrocytes in bone marrow and lung homogenates were lysed for 1 minute using osmotic lysis buffer.

In vivo mouse studies

HDM-driven AAI.

To induce acute HDM-mediated AAI, mice were first sensitized intranasally (i.n.) with 1 or 10 μg (as indicated in the figures) HDM (Greer; endotoxin: 1397.5 EU/vial; protein: 5.59 mg/vial) dissolved in 40 μL PBS (Invitrogen) or with PBS alone. On days 7–10, mice were exposed i.n. to 10 μg HDM (in 40 μL PBS) for 5 consecutive days. During HDM/PBS treatments, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. Mice were sacrificed and analyzed 4 days after the last challenge. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) was obtained by flushing of the lungs 3 times with 1 mL PBS containing 0.5 mM EDTA (MilliporeSigma). Chronic HDM-mediated AAI was induced and lung function was measured following increasing doses of nebulized methacholine (0.4–25 mg/mL) using a restrained whole-body plethysmograph (EMKA) under urethane sedation.

In vivo OVA-specific T cell responses.

In brief, CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleen and lymph nodes of OTII mice using a CD4+ T cell MACS isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and were stained with 0.5 mM CFSE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 minutes at 37°C. A total of 2 × 106 OTII cells were transferred i.v. into WT recipients. The next day, mice were exposed i.n. to 5 or 20 μg OVA (Endotoxin-free, Hyglos) and 50 μg HDM. Animals were sacrificed 72 hours later for FACS analyses.

In vivo transfer of polarized OTII Th2 cells.

To study the role of Notch in the maintenance of Th2 responses, 10 × 106 in vitro–polarized Th2 OTII cells were injected in WT recipients. For Th2 polarization, naive T cells were isolated from spleen and lymph nodes of OTII mice using a CD4+ T cell MACS isolation kit and were subsequently sorted using a FACSAria equipped with BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Cells were selected on negativity for DAPI (Invitrogen). Doublets were depleted using side scatter and forward scatter width and height, and cells were further gated as CD4+CD62L+. A list of all used fluorochrome-labeled antibodies can be found in Supplemental Table 1. CD4+CD62L+CD44– naive T cells were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom plates precoated with 10 μg/mL anti-CD3 (BD Biosciences, 145-2C11) and 10 μg/mL anti-CD28 (BD Biosciences, 37.51) in PBS (65 μL per well) in T cell medium (IMDM containing 10% FCS, 5 × 10–5 M β-mercaptoethanol, 1× GlutaMAX, and 55 μg/mL gentamicin; Lonza) for 7 days in the presence of IL-4 (10 ng/mL; PeproTech), anti–IFN-γ (5 μg/mL; BD Biosciences B27), and anti–IL-12/23 p40 (5 μg/mL; BD Biosciences C17.8). After transfer of polarized Th2 cells, mice were challenged intratracheally for 4 consecutive days with 50 μg OVA and 10 μg HDM. Mice were analyzed 1 day after the last challenge. We did not administer OVA into the lung before Th2 cell transfer to preclude direct migration of these cells into allergen-primed lungs, thereby bypassing the MedLNs.

Adoptive transfer of T cell fractions from MedLNs.

To evaluate the lung homing capacity of Notch-deficient MedLN OTII Th2 cells, we transferred in vitro–polarized WT or Notch-deficient OTII Th2 cells into WT mice, followed by i.n. challenges with OVA and HDM as described above. One day after the last OVA/HDM treatment, mice were sacrificed and total CD4+ T cells were purified from 5 pooled MedLNs using a CD4+ T cell MACS isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec), followed by labeling with CellTrace Far Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, 2 × 106 to 4 × 106 total CD4+ T cells, of which approximately 10%–30% were OTII cells, were adoptively transferred into secondary WT recipient mice, which were sensitized intratracheally with 50 μg OVA and 10 μg HDM 1 day before transfer. Secondary recipients were sacrificed 3 hours after transfer for analysis by flow cytometry.

Analysis of Notch ligand induction in MedLNs.

To investigate the induction of Notch ligands on stromal cells and DCs in the MedLNs by HDM, WT mice were treated i.n. with 50 μg HDM dissolved in 40 μL PBS or with PBS alone and sacrificed after 72 hours.

DC–OTII cell cocultures

GM-CSF bone marrow–derived DCs were generated as previously described (55, 62) and stimulated overnight with 5 μg/mL HDM or 100 ng/mL LPS (Enzo Life Sciences) in combination with variable concentrations of endotoxin-free OVA as indicated in the figure legends. Naive T cells were isolated from spleen and lymph nodes of OTII mice using a CD4+ T cell MACS isolation kit and were subsequently sorted using a FACSAria equipped with BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences), as described above. GM-CSF bone marrow–derived DCs (5 × 103) were cultured with 1 × 105 CFSE-labeled naive T cells for 4 days at 37°C, after which cells were analyzed using flow cytometry.

Th cell cultures

Naive T cells were obtained as described above and polarized to Th2 conditions as described above. For Th1 polarization, naive T cells were cultured on anti-CD3/CD28–coated plates in T cell medium (see above) with 10 ng/mL IL-12 (R&D Systems) and 5 mg/mL anti–IL-4 (provided by Louis Boon, Bioceros, Utrecht, Netherlands). For Th17 polarization, naive T cells were cultured on anti-CD3/CD28–coated plates in T cell medium with anti–IL-4 (5 μg/mL), anti–IFN-γ (5 μg/mL), TGF-β (3 ng/mL; R&D Systems), and IL-6 (20 ng/mL; R&D Systems).

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were stained with a mixture of fluorochrome-labeled antibodies in FACS buffer containing 0.25% BSA, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.05% NaN3 in PBS (55, 57). A list of all fluorochrome-labeled antibodies that were used can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Data were acquired using an LSR II flow cytometer and FACSDiva software 6.1 (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo 9.8.5 (Tree Star Inc.).

To measure phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein by flow cytometry, total spleen cells were stained for extracellular markers and stimulated for 3 hours with combinations of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (both BD Biosciences). Cells were then fixed with Cytofix and permeabilized with Phosflow Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences) and stained for anti–phospho–S6 ribosomal protein (S240/244; Cell Signaling Technology).

Histology

Five-micrometer-thick paraffin-embedded lung sections were obtained and stained using H&E, periodic acid-Schiff, or Masson’s trichrome (MilliporeSigma). For immunohistochemistry, lungs were inflated with OCT compound, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80°C; frozen sections were fixed in acetone, endogenic peroxidase was blocked, and immunohistochemical double staining was performed using standard procedures. Antibodies are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Cytokine and immunoglobulin measurements

Cytokines were quantified by commercial ELISA for IL-5 (eBioscience), IL-13 (R&D Systems), IgE (BD Biosciences), and IgG1 (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. HDM-specific IgE and IgG1 (antibodies from BD Biosciences) were measured as follows. A Nunc MaxiSorp flat-bottom 96-well plate (MilliporeSigma) was coated with 2 μg/mL anti-mouse IgE (for HDM-specific IgE; BD Pharmingen) or 10 μg/mL HDM (for HDM-specific IgG1) in PBS overnight at 4°C. The next day the plates were washed 3 times with wash buffer (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) and blocked for 1 hour with either PBS containing 1% BSA (for HDM-specific IgE) or ELISA buffer [50 mM Tris-(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, 136.9 mM NaCl, 2 mM ethylene-diamine-tetraacetic acid, 0.5% BSA, and 0.05% Tween, dissolved in 1000 mL H2O, pH 7.2]. Serum samples were incubated at room temperature for 2 hours and washed 3 times. For HDM-specific IgE, samples were labeled with biotin-conjugated HDM, incubated for 2 hours, washed 3 times, and incubated with HRP for 1 hour. For HDM-specific IgG1, samples were labeled for 1 hour with 0.5 μg/mL biotinylated IgG1 followed by incubation with HRP for 30 minutes. After labeling, plates were washed 3 times and incubated with 0.4 mg/mL o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD; MilliporeSigma) for 20 minutes. Reactions were stopped through addition of 4 M H2SO4, and plates were read at 490 nm.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted using RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was synthesized into cDNA using RevertAid H Minus Reverse Transcriptase and random hexamer primers in the presence of RiboLock RNAse inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For quantitative RT-PCR reactions, probes from the Universal ProbeLibrary Set (Roche Applied Science) and TaqMan Universal Master Mix were used (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed using an Applied Biosystems Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Primers were designed using transcript sequences obtained from Ensembl (https://www.ensembl.org) and were specific for Dtx1 (forward: 5′-CGCCTGATGAGGACTGTACC-3′; reverse: 5′-CCCTCATAGCCAGATGCTGT-3′; probe 28), Cx3cr1 (forward: 5′-aagttcccttcccatctgct-3′; reverse: 5′-caaaattctctagatccagttcagg-3′; probe 10), Sell (forward: 5′-ggagcatctggaaactggtc-3′; reverse: 5′-ttgatctttgagaaacttctgtttg-3′; probe 21), Jag1 (forward: 5′-ACCAGAACGGCAACAAAACT-3′; reverse: 5′-GACCCATGCTTGGGACTG-3′; probe 97), Jag2 (forward: 5′-CGTCATTCCCTTTCAGTTCG-3′; reverse: 5′-CCTCATCTGGAGTGGTGTCA-3′; probe 95), Dll1 (forward: 5′-GGGCTTCTCTGGCTTCAAC-3′; reverse: 5′-TAAGAGTTGCCGAGGTCCAC-3′; probe 103), and Dll4 (forward: 5′-GAGGAACGAGTGTGTGATTGC-3′; reverse: 5′-GTCCCATACAGGATGCAATGT-3′; probe 3). Expression levels were normalized to Gapdh levels (forward: 5′-TTCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC-3′; reverse: 5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGA-3′; probe TGCATCCTGCACCACCAACTG). Primers were checked for specificity and efficacy using standard criteria.

RNA sequencing

RNA was extracted from the following populations: (a) WT (N1N2+/+) and Notch-deficient (N1N2ΔCD4/ΔCD4) OTII Th2 cells directly after in vitro polarization (n = 2 biological replicates per genotype) and 5 days after in vivo transfer and OVA/HDM treatment from MedLNs (n = 3 WT and n = 4 Notch-deficient biological replicates), and (b) WT (N1N2+/+) Gata3+ Th2 (YFP+) cells isolated from BAL fluid or MedLNs of GATIR mice on an acute HDM-driven AAI protocol (n = 3 biological replicates per tissue). Biological replicate RNA samples were prepared from pooled cell populations collected from 3–5 mice per genotype. RNA samples were then used to prepare RNA-Seq libraries with Smart-seq2 methodology and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2500 (single read mode, 51 bp read length) according to the Illumina TruSeq Rapid v2 protocol.

Computational analysis of RNA-Seq data

HISAT2 was used to align reads to the mouse genome (mm10 build) (63). Scaling of samples as well as statistical analysis was executed using the R package DESeq2 (64) as implemented in HOMER (getDiffExpression.pl -DESeq2) (65); genes with more than 0.5 absolute log2 fold change and adjusted P less than 0.05 (Wald test, corrected for multiple testing) were considered differentially expressed (Supplemental Table 2). Reads per kilobase million (RPKM) values per gene were generated using HOMER (analyzeRepeats.pl rna mm10 -count exons -condenseGenes -norm 1e7 -rpkm). Principal component analyses, hierarchical clustering (Ward’s method), and the generation of volcano plots and Venn diagrams were conducted using standard R scripts [i.e., prcomp(), hclust(), ggplot(); executed from R Studio v1.1.383]. Pathway enrichments were calculated with Metascape (http://metascape.org) or Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp; using a preranked list of differentially expressed genes ordered by fold changes).

Statistics

For statistical analysis of all data except for the analysis of RNA-Seq experiments (see above), a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test with correction for multiple testing (FDR method) was performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.01). P values below 0.05 were considered significant.

RNA-Seq data were deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO) under accession number GSE125358.

Study approval

All experiments involving animals were approved by the Erasmus MC Animal Ethics Committee.

Author contributions

IT designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. AK and AVS designed, performed, and analyzed experiments. MJWDB, ML, MVN, AVDB, IMB, and OBJC performed experiments. WFJVIJ supervised RNA sequencing efforts. RS designed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. RWH designed experiments, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Rip, W.M.E. Hendrikx, F. Cornelissen, and members of the Biomics core and Animal Facilities (Erasmus MC Rotterdam) as well as L. Hesse (University Medical Center Groningen) for their technical assistance. We also acknowledge T. Cupedo (Erasmus MC) and D. Amsen (Sanquin, Amsterdam) for helpful discussions, as well as H.J. Fehling (Ulm, Germany) and F. Radtke (Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing the Gata3-YFP reporter (GATIR) mice and Dll4ΔCcl19/ΔCcl19 mice, respectively. This study was partly supported by Lung Foundation Netherlands grants 3.2.12.087 and 3.2.12.067. RS is supported by a Dutch Research Council (NWO) Veni Fellowship (grant 91617114) and an Erasmus MC Fellowship.

Version 1. 04/07/2020

In-Press Preview

Version 2. 06/02/2020

Electronic publication

Version 3. 07/01/2020

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2020, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2020;130(7):3576–3591.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI128310.

Contributor Information

Irma Tindemans, Email: i.tindemans@erasmusmc.nl.

Anne van Schoonhoven, Email: a.schoonhoven@erasmusmc.nl.

Alex KleinJan, Email: a.kleinjan@erasmusmc.nl.

Marjolein J.W. de Bruijn, Email: j.w.debruijn@erasmusmc.nl.

Melanie Lukkes, Email: melanielukkes@hotmail.com.

Menno van Nimwegen, Email: m.vannimwegen@erasmusmc.nl.

Anouk van den Branden, Email: anoukvdbranden@hotmail.com.

Ingrid M. Bergen, Email: i.bergen@erasmusmc.nl.

Wilfred F.J. van IJcken, Email: w.vanijcken@erasmusmc.nl.

Ralph Stadhouders, Email: r.stadhouders@erasmusmc.nl.

Rudi W. Hendriks, Email: r.hendriks@erasmusmc.nl.

References

- 1.Papi A, Brightling C, Pedersen SE, Reddel HK. Asthma. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):783–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Barrier epithelial cells and the control of type 2 immunity. Immunity. 2015;43(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Ploeg EK, Carreras Mascaro A, Huylebroeck D, Hendriks RW, Stadhouders R. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells in human respiratory disorders. J Innate Immun. 2020;12(1):47–62. doi: 10.1159/000496212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker JA, McKenzie ANJ. TH2 cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(2):121–133. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89(4):587–596. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang DH, Cohn L, Ray P, Bottomly K, Ray A. Transcription factor GATA-3 is differentially expressed in murine Th1 and Th2 cells and controls Th2-specific expression of the interleukin-5 gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(34):21597–21603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tindemans I, Serafini N, Di Santo JP, Hendriks RW. GATA-3 function in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2014;41(2):191–206. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amsen D, Helbig C, Backer RA. Notch in T cell differentiation: all things considered. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(12):802–814. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117(4):515–526. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amsen D, et al. Direct regulation of Gata3 expression determines the T helper differentiation potential of Notch. Immunity. 2007;27(1):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang TC, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Del Bianco C, Knoblock DM, Blacklow SC, Pear WS. Notch directly regulates Gata3 expression during T helper 2 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;27(1):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka S, et al. The interleukin-4 enhancer CNS-2 is regulated by Notch signals and controls initial expression in NKT cells and memory-type CD4 T cells. Immunity. 2006;24(6):689–701. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowell CS, Radtke F. Notch as a tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(3):145–159. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radtke F, et al. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10(5):547–558. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pui JC, et al. Notch1 expression in early lymphopoiesis influences B versus T lineage determination. Immunity. 1999;11(3):299–308. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radtke F, MacDonald HR, Tacchini-Cottier F. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):427–437. doi: 10.1038/nri3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu L, et al. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202(8):1037–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang JH, et al. γ-Secretase inhibitor reduces allergic pulmonary inflammation by modulating Th1 and Th2 responses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(10):875–882. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-893OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang S, Han S, Chen J, Li X, Che H. Inhibition effect of blunting Notch signaling on food allergy through improving TH1/TH2 balance in mice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(1):94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.KleinJan A, et al. The Notch pathway inhibitor stapled α-helical peptide derived from mastermind-like 1 (SAHM1) abrogates the hallmarks of allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):76–85.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tindemans I, et al. Increased surface expression of NOTCH on memory T cells in peripheral blood from patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(2):769–771.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailis W, et al. Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple helper T cell programs independently of cytokine signals. Immunity. 2013;39(1):148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tindemans I, Peeters MJW, Hendriks RW. Notch signaling in T Helper cell subsets: instructor or unbiased amplifier? Front Immunol. 2017;8:419. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCright B, Lozier J, Gridley T. Generation of new Notch2 mutant alleles. Genesis. 2006;44(1):29–33. doi: 10.1002/gene.20181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfer A, et al. Inactivation of Notch 1 in immature thymocytes does not perturb CD4 or CD8T cell development. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(3):235–241. doi: 10.1038/85294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coquet JM, et al. Interleukin-21-producing CD4(+) T cells promote type 2 immunity to house dust mites. Immunity. 2015;43(2):318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ballesteros-Tato A, Randall TD, Lund FE, Spolski R, Leonard WJ, León B. T follicular Helper cell plasticity shapes pathogenic T Helper 2 cell-mediated immunity to inhaled house dust mite. Immunity. 2016;44(2):259–273. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fasnacht N, et al. Specific fibroblastic niches in secondary lymphoid organs orchestrate distinct Notch-regulated immune responses. J Exp Med. 2014;211(11):2265–2279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dell’Aringa M, Reinhardt RL. Notch signaling represents an important checkpoint between follicular T-helper and canonical T-helper 2 cell fate. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11(4):1079–1091. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vroman H, et al. Development of eosinophilic inflammation is independent of B-T cell interaction in a chronic house dust mite-driven asthma model. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(4):551–564. doi: 10.1111/cea.12834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.KleinJan A, et al. Enforced expression of Gata3 in T cells and group 2 innate lymphoid cells increases susceptibility to allergic airway inflammation in mice. J Immunol. 2014;192(4):1385–1394. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nawijn MC, et al. Enforced expression of GATA-3 in transgenic mice inhibits Th1 differentiation and induces the formation of a T1/ST2-expressing Th2-committed T cell compartment in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167(2):724–732. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Hamburg JP, et al. Enforced expression of GATA3 allows differentiation of IL-17-producing cells, but constrains Th17-mediated pathology. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(9):2573–2586. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laky K, Evans S, Perez-Diez A, Fowlkes BJ. Notch signaling regulates antigen sensitivity of naive CD4+ T cells by tuning co-stimulation. Immunity. 2015;42(1):80–94. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perumalsamy LR, Nagala M, Sarin A. Notch-activated signaling cascade interacts with mitochondrial remodeling proteins to regulate cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(15):6882–6887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sade H, Krishna S, Sarin A. The anti-apoptotic effect of Notch-1 requires p56lck-dependent, Akt/PKB-mediated signaling in T cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(4):2937–2944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vahedi G, et al. Super-enhancers delineate disease-associated regulatory nodes in T cells. Nature. 2015;520(7548):558–562. doi: 10.1038/nature14154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stadhouders R, et al. Epigenome analysis links gene regulatory elements in group 2 innate lymphocytes to asthma susceptibility. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(6):1793–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikhak Z, Fukui M, Farsidjani A, Medoff BD, Tager AM, Luster AD. Contribution of CCR4 and CCR8 to antigen-specific T(H)2 cell trafficking in allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(1):67–73.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mionnet C, et al. CX3CR1 is required for airway inflammation by promoting T helper cell survival and maintenance in inflamed lung. Nat Med. 2010;16(11):1305–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohlmeier JE, et al. CXCR3 directs antigen-specific effector CD4+ T cell migration to the lung during parainfluenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2009;183(7):4378–4384. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikhak Z, Strassner JP, Luster AD. Lung dendritic cells imprint T cell lung homing and promote lung immunity through the chemokine receptor CCR4. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1855–1869. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen SD. Ligands for L-selectin: homing, inflammation, and beyond. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:129–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.090501.080131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cyster JG, Schwab SR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:69–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakai A, Hayano Y, Furuta F, Noda M, Suzuki K. Control of lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes through β2-adrenergic receptors. J Exp Med. 2014;211(13):2583–2598. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benechet AP, et al. T cell-intrinsic S1PR1 regulates endogenous effector T-cell egress dynamics from lymph nodes during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(8):2182–2187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516485113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlson CM, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 2006;442(7100):299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Z, et al. ECM1 controls T(H)2 cell egress from lymph nodes through re-expression of S1P(1) Nat Immunol. 2011;12(2):178–185. doi: 10.1038/ni.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bankovich AJ, Shiow LR, Cyster JG. CD69 suppresses sphingosine 1-phosophate receptor-1 (S1P1) function through interaction with membrane helix 4. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(29):22328–22337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newman R, et al. Maintenance of the marginal-zone B cell compartment specifically requires the RNA-binding protein ZFP36L1. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(6):683–693. doi: 10.1038/ni.3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinnell N, et al. The PIAS-like coactivator Zmiz1 is a direct and selective cofactor of Notch1 in T cell development and leukemia. Immunity. 2015;43(5):870–883. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):753–763. doi: 10.1038/nri2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sainson RC, et al. TNF primes endothelial cells for angiogenic sprouting by inducing a tip cell phenotype. Blood. 2008;111(10):4997–5007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gopinathan G, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates defective angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2015;75(15):3098–3107. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tindemans I, et al. Notch signaling in T cells is essential for allergic airway inflammation, but expression of the Notch ligands Jagged 1 and Jagged 2 on dendritic cells is dispensable. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(4):1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oliphant CJ, et al. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity. 2014;41(2):283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li BW, et al. T cells are necessary for ILC2 activation in house dust mite-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(6):1392–1403. doi: 10.1002/eji.201546119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.GeurtsvanKessel CH, et al. Dendritic cells are crucial for maintenance of tertiary lymphoid structures in the lung of influenza virus-infected mice. J Exp Med. 2009;206(11):2339–2349. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tanigaki K, et al. Notch-RBP-J signaling is involved in cell fate determination of marginal zone B cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(5):443–450. doi: 10.1038/ni793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based alpha- and beta-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76(1):34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li BWS, et al. Group 2 Innate lymphoid cells exhibit a dynamic phenotype in allergic airway inflammation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1684. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kool M, et al. Alum adjuvant boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(4):869–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38(4):576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.