Abstract

RNA nanotechnology seeks to create nanoscale machines by repurposing natural RNA modules. The field is slowed by the current need for human intuition during 3D structural design. Here, we demonstrate that three distinct problems in RNA nanotechnology can be reduced to a pathfinding problem and automatically solved through an algorithm called RNAMake. First, RNAMake discovers highly stable single-chain solutions to the classic problem of aligning a tetraloop and sequence-distal receptor, with experimental validation from chemical mapping, gel electrophoresis, solution X-ray scattering, and 2.55 Å resolution crystallography. Second, RNAMake automatically generates structured tethers that integrate 16S and 23S ribosomal RNAs into single-chain rRNAs that remain uncleaved by ribonucleases and assemble onto mRNA. Last, RNAMake enables automated stabilization of small-molecule binding RNAs, with designed tertiary contacts improving binding affinity of the ATP aptamer and improving fluorescence and stability of the Spinach RNA in cell extracts, and in living E. coli cells.

One sentence summary:

Automated 3D design produces rapid and near-atomically accurate predictions of RNA tertiary structure as well as the ability to generate complex RNA machines such as functional single-stranded tethered ribosomes, and enhancement of the binding properties of small-molecule RNA aptamers.

RNA-based nanotechnology is an emerging field that harnesses RNA’s unique structural properties to create new nanostructures and machines1,2. Perhaps more so than for other biomolecules, RNA tertiary structure is composed of discrete and recurring components known as tertiary ‘motifs’3. Along with the helices that they interconnect, many of these structural motifs appear highly modular; that is, each motif folds into a well-defined three-dimensional (3D) structure in a broad range of contexts2,4–6. By exploiting symmetry, motif repetition, expert modelling, and computational tools for visualization and modelling flexibility, these motifs have been assembled into new polyhedra, sheets, and cargo-carrying nanoparticles for biomedical use7–10 and refs. therein). Despite these advances, current methods still rely on human intuition, and the field cannot yet generate RNAs as sophisticated as natural RNA machines, which are asymmetric, too large to be solved by 3D RNA structure prediction methods, and composed of vast repertoires of distinct interacting motifs, most of which are not yet well characterized11–13.

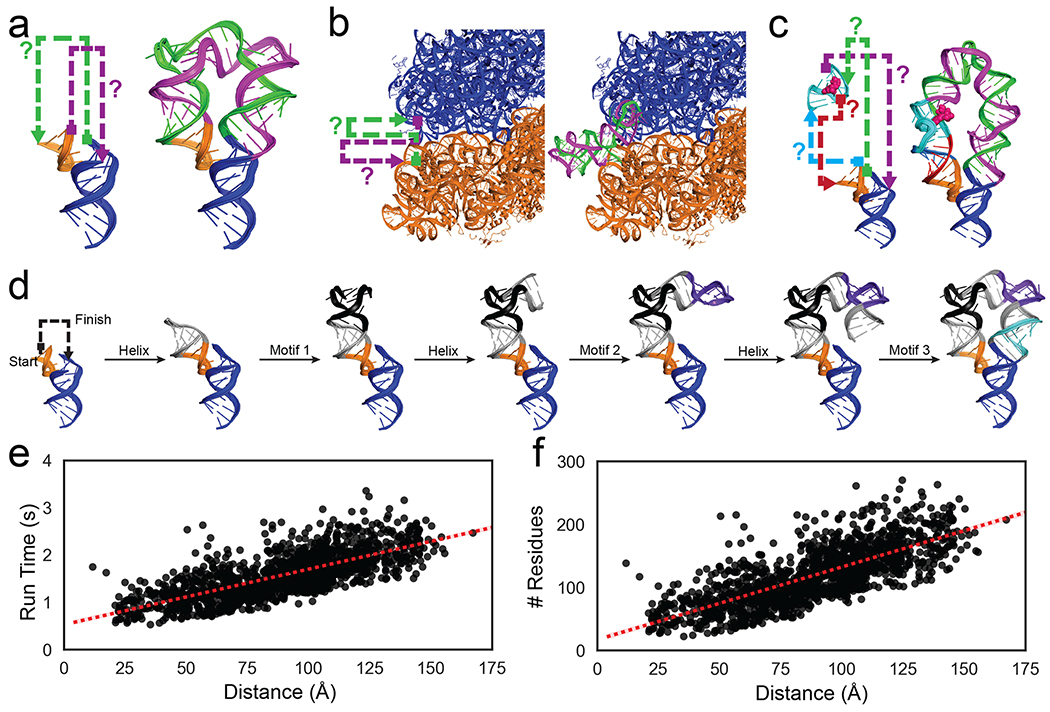

We present here a new approach to 3D RNA design, based on the recognition that numerous recurring problems in the field can be cast into the same ‘pathfinding’ problem (Figure 1). First, a founding problem of RNA nanotechnology involves designing a compact nanostructure that aligns the two parts of the tetraloop/tetraloop-receptor (TTR) so that they can form a tertiary contact upon RNA chain folding (Figure 1a). This task requires finding RNA sequences that interconnect the 5′ and 3′ ends of the tetraloop (orange) to the 3′ and 5′ ends of the tetraloop receptor, respectively (blue, Figure 1a). The problem has previously been solved through a combination of expert manual modelling and symmetric assembly of multiple chains5,14. In all cases, an important guiding principle – sometimes called RNA architectonics4 – has been to design the intermediate RNA chains so that they form RNA modules previously seen in Nature, including both canonical double-stranded helices and noncanonical RNA motifs that twist and translate between two desired helical endpoints at the tetraloop and the receptor. We call this design task the ‘RNA motif pathfinding problem’. The general complexity of this pathfinding task has prevented design of asymmetric, single-chain solutions to the TTR stabilization problem.

Figure 1: Problems in RNA nanotechnology reduced to RNA motif pathfinding problems and solved by RNAMake.

(a) ‘miniTTRs’ require two strands (green, purple) between tetraloop (orange) and tetraloop-receptor (blue); (b) tethered ribosomes require two strands (green, purple) to link the small subunit (orange) to the large subunit (blue). c) ‘Locking’ a small-molecule binding aptamer (cyan; ATP molecule in pink spheres) by designing four strands (green, purple, teal, magenta) to a peripheral tertiary contact (orange, blue). d) Demonstration of RNAMake design algorithm, which builds an RNA path via the successive addition of motifs and helices from a starting base pair to the ending base pair. e-f) computational efficiency for RNAMake to design connections between each pair of hairpins on the 50S E. coli ribosome. Run time scales linearly with problem size, as measured by (e) translational distance between helical endpoints or (f) number of residues required for segments (see Figure S14 for utilizing higher order junctions).

A second problem is highly analogous to the TTR stabilization problem but is more difficult. Efforts to select engineered ribosomes with mRNA decoding, polypeptide synthesis, and protein excretion functions optimized for new substrates might be dramatically accelerated through the design of integrated ribosomes. An important step towards this goal involves tethering the two 23S and 16S rRNAs of the ribosome into a single RNA strand that supports E. coli. growth15–18. 3D designs for the tether would require solving the RNA motif pathfinding problem over >100 Å distances and avoiding steric collisions with the ribosome’s RNA and protein components (blue and orange strands, Figure 1b). Even after identification of appropriate helix endpoints, this difficult design challenge previously took more than a year to solve using trial-and-error refinement based in vivo assays16,17 or ad hoc combination of noncanonical motifs without explicit 3D modelling15,18.

A third problem involves a more complex instance of two RNA motif pathfinding problems (green, purple, red, and teal lines, Figure 1c). A ubiquitous task in RNA nanotechnology is the selection of ‘aptamer’ RNAs that sense or carry target small molecules, such as adenosine 5´-triphosphate or fluorophores19. Despite recent progress20,21, improving aptamers requires numerous rounds of tedious selections, with few design tools available to guide consistent improvements. The desired stabilizations might be achieved by peripheral tertiary contacts that extend out of either end of an aptamer and encircle these aptamers, bracing them into their functional 3D arrangements (Figure 1c) – analogous to the tertiary contacts that ‘lock’ natural riboswitch aptamers22. However, such rational design has not been carried out due to the difficulty of finding the required four strands that interconnect a given aptamer structure and a tertiary contact.

Here we present a 3D RNA design algorithm, RNAMake, which solves all three cases of the RNA motif pathfinding problem, described above. Gauntlets of structural and functional measurements test that these computationally designed nanostructures, ribosomes, and ATP and fluorescent RNA aptamers achieve their design goals, without requiring any further rounds of trial and error.

The RNAMake algorithm and motif library

RNAMake uses a 3D motif library drawn from all unique, publicly deposited crystallographic RNA structures and an efficient algorithm to discover combinations of these motifs and helices that solve the RNA motif pathfinding problem (see Methods, Table S1). The final set of noncanonical motifs contained 461 unique two-way junctions, 61 higher-order junctions, 290 variable-length hairpins, and 89 tertiary contacts. The pathfinding algorithm assembles canonical helical segments ranging from 1 to 22 base pairs with these noncanonical structural motifs, step-by-step in a depth-first search (Figure 1d and Methods). The canonical helical segments are idealized and sequence invariant 23; after the completion of 3D structural design, they are filled in with sequences that best match the target secondary structure and minimize alternative secondary structures 24. Due to its efficient algorithmic implementation, RNAMake is able to rapidly find solutions; the run time scales linearly with problem size, and discovery of exceptionally long double-stranded RNA paths that snake around the entire ribosome takes less than 3 seconds (run on a Macbook Pro 2016, 2.9 GHz Intel Core i7) (Figure 1e–f).

RNAMake solutions to the TTR problem achieve high stability

The problem of creating a well-folded RNA nanostructure was first solved two decades ago by repurposing the well-characterized tetraloop/receptor (TTR) tertiary contact to bring together two separate RNA chains5, analogous to the P4-P6 domain of the Tetrahymena group I self-splicing intron and other natural functional RNAs. While later RNA nanotechnology studies used the TTR module and other structural motifs to design different nanostructures, the original and later designs have all been multi-chain assemblies25–29. We chose to test RNAMake on the TTR problem due to the prospect of achieving the first de novo single-chain solutions to this fundamental problem, which we hypothesized might also help crystallization. We generated 16 diverse single chain solutions with RNAMake, which we called ‘miniTTR’ designs.

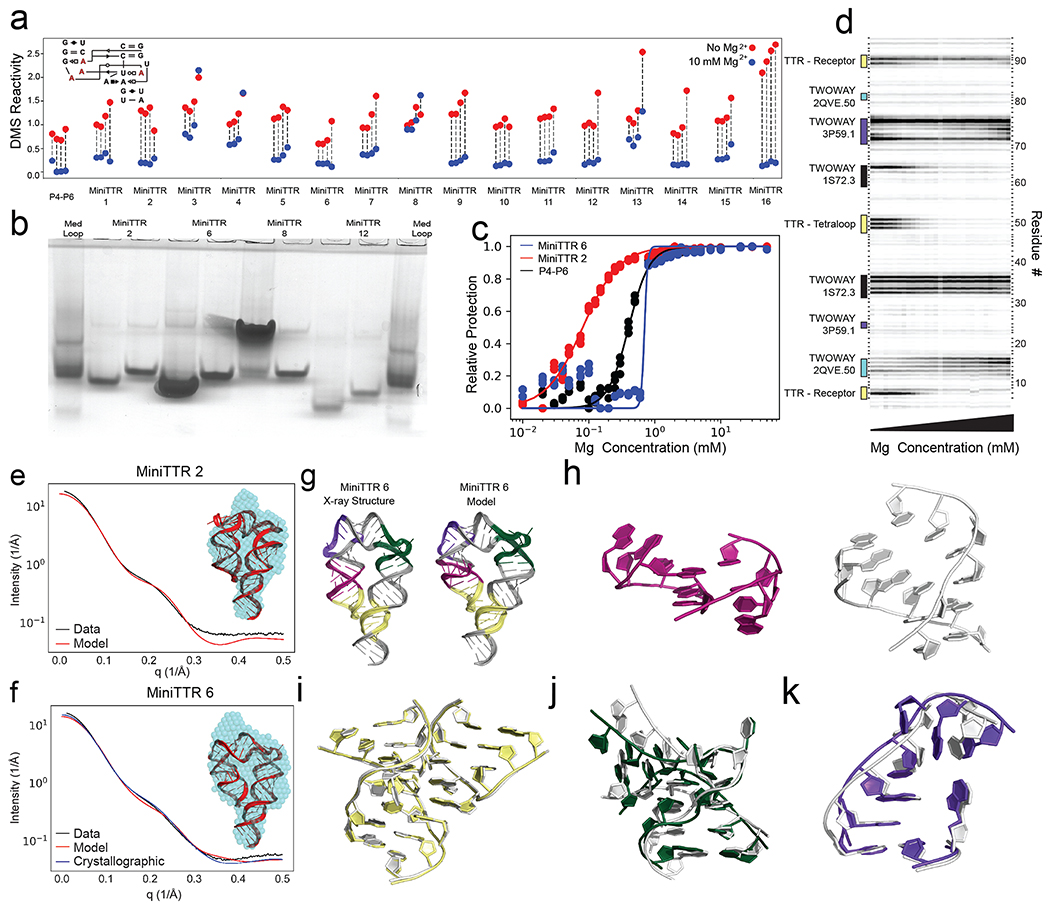

Standard biochemical and biophysical assays for RNA structure confirmed folding for the majority of the miniTTR designs. We tested the miniTTR RNAs for correct secondary structure and tertiary contact formation with single nucleotide resolution chemical mapping (SHAPE and DMS, Figure S1b; Figure 2a gives DMS at tetraloop and receptor nucleotides); for compact folds through native gel electrophoresis and mutational analysis (Figure 2b; Figure S1c); and for tertiary stability through Mg2+ binding curves (Figure 2c–d; Table S2). Overall, 11 of the 16 designs passed these experimental screens (details given in Supplemental Results and Table S3). Several miniTTR constructs required less than 1 mM Mg2+ to fold stably, similarly to or better than reported midpoints for natural TTR-contains RNA nanostructures. Indeed, miniTTR 2 and miniTTR 16 exhibited folding stabilities better than the P4-P6 RNA in side-by-side assays (Figure 2c). Furthermore, miniTTR 6 has a much sharper Mg2+ dependence than P4-P6 with an apparent Hill coefficient of over 10 (Figure 2c). The stability of the RNAMake designs was particularly notable given that P4-P6 and other natural TTR-containing RNAs are larger than the miniTTR designs and have additional stabilizing tertiary contacts30–32 and other attempts to make artificial minimized TTR constructs have given significantly worse stabilities33.

Figure 2: Solving the TTR design problem.

a) Quantification of DMS reactivity in the absence of Mg2+ (red) and with 10 mM Mg2+ (blue) for RNAMake-designed miniTTR constructs and the P4-P6 domain of the Tetrahymena ribozyme as a large natural RNA comparison. Diagram (inset) shows the four adenosines in the tetraloop/tetraloop-receptor (red) that undergo protection upon Mg2+-dependent folding. b) Native gel assays testing whether mutation of GAAA tetraloop (left lane) to UUCG mutant (right lane) disrupts the miniTTR tertiary fold and slows its mobility. ‘MedLoop’ lanes are a control RNA with similar size 58. Figure S3b gives other remaining constructs. c) Quantification of the miniTTR folding stability based on Mg2+ binding curves read out by DMS mapping for miniTTR 6 (blue), miniTTR 2 (red) and P4-P6 (black). d) Raw data from the Mg2+ titration of miniTTR 2, highlighting the change in DMS reactivity in the TTR and the motifs used in the design. e-f) SAXS analysis: Experimental intensity versus scattering amplitude and low-resolution reconstruction derived from experimental scattering profiles (blue beads, inset) overlaid on RNAMake-designed model (cartoon, inset) for (e) miniTTR 2 and (f) miniTTR 6. In (f), SAXS prediction from miniTTR crystal structure is also shown (blue). g-l) X-ray crystal structure of MiniTTR 6 tests accuracy of RNAMake model at atomic resolution: (g) overall RNAMake and X-ray structure, and magnified views of (h) triple mismatch motif from ribosome, (i) tetraloop/tetraloop-receptor, (j) kink-turn motif, and (k) right angle turn. In (h-k), crystal structures are white.

After the gel-based and chemical mapping tests above, we tested whether the RNAMake designs might allow crystallization and thereby enable high-resolution characterization of the structural accuracy of the designs. After SAXS measurements confirmed monomeric at high RNA concentrations (> 1 μM; Supplemental Results; Figure 2e–f, Figure S2a–b), we were able to obtain crystals of miniTTR 6 that diffracted at 2.55 Å resolution (I/σ of 1.0) (Figure 2g; Table S10). The crystal structure and the RNAMake model agreed with an all-heavy-atom RMSD of 4.2 Å, better than the nanometer-scale accuracy typically sought in RNA nanotechnology. The primary discrepancy between our modelled 3D structure and the crystal structure was a single motif, a triple mismatch drawn from the large ribosomal subunit (Figure 2h, right). This motif formed multiple consecutive non-canonical base pairs with high B-factors in our miniTTR 6 crystal instead of the conformation found in the ribosomal structure, which involved flipped out adenosines (residues: O2360-O2363, O2424-O2426, PDB:1S72) (Figure 2h, left). Other motifs in the design achieved near-atomic accuracy, including the TTR tertiary contact (RMSD 0.45 Å; Figure 2i), a kink-turn variant drawn from the archaeal 50S ribosomal subunit (RMSD 2.0 Å; Figure 2j)34, and a ‘right angle turn’ drawn from a viral internal ribosomal entry site domain (RMSD 1.28 Å; Figure 2k)25.

Automated 3D design of tethered ribosomal subunits

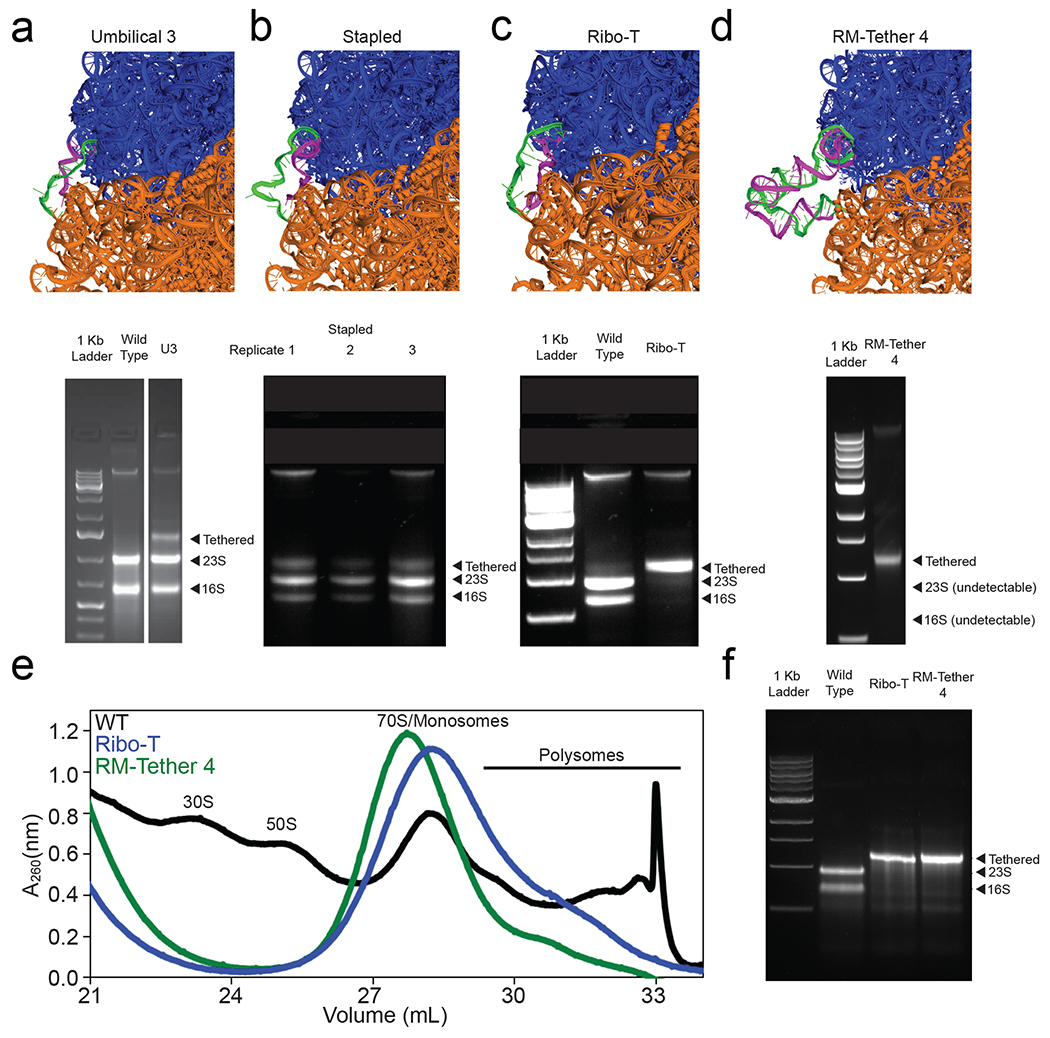

After testing RNAMake’s performance in designing compact RNA nanostructures, we evaluated whether it might solve a practical problem involving nanostructures that must traverse long distances (compare Figure 1a and 1b). The ribosome is a ribonucleoprotein machine dominated by two extensive RNA subunits, the 16S and 23S rRNAs. In previous work two of us (MCJ, EDC) constructed a tethered ribosome called Ribo-T, in which the large and small subunit rRNAs were connected by an RNA tether to form a single subunit ribosome. In that work, the major bottleneck involved a year of numerous trial-and-error iterations to identify RNA tethers that were not cleaved by ribonucleases in vivo when wild type ribosomes were replaced in the Squires strain of E. coli17. The Squires strain cells lack genetic rRNA alleles, surviving off plasmids that can be exchanged using positive and negative selections. Early failure rounds involving ribosomes from our and other studies are shown in Figure 3a–b and success with Ribo-T in Figure 3c. Nevertheless, the current tethers in Ribo-T are unstructured and unlikely to remain stable if other modules are incorporated (Figure 3c). We hypothesized that automated design by RNAMake might give structured, chemically stable tethers for this design problem.

Figure 3: The ribosome tethering problem.

a-d) Modelling (top panel) of tethers (green and magenta strands) connecting 16S and 23S rRNA into a single ribosomal RNA; and agarose gel electrophoresis (bottom panel) of RNA extracted from E. coli (Squires strain) in which wild type ribosomes were completely replaced with the following designed molecules: (a) an early U3 tether (Umbilical 3) designed by the Jewett lab, cleaved into two bands in vivo, (b) (top) Stapled ribosomes developed by a separate group15 (three replicates shown), also cleaved in this plasmid context and strain in vivo, (c) successful Ribo-T design, developed after a year of manual trial-and-error to withstand cleavage in vivo, (d) RM-Tether 4, design automatically generated by RNAMake, which also presents as a single band in vivo. e) Sucrose gradient fractionation prepared from in vitro ISAT reactions expressing wild type ribosomes (black), Ribo-T v1.0 (blue), and RM-Tether 4 (green). Peaks corresponding to small subunits (30S), large subunits (50S), monosomes/70S, and polysomes are indicated; see, e.g., ref. 37 for standard assignment of peaks. f) Agarose electrophoresis analysis confirms that the polysome fraction of (e) is composed of tethered ribosomes. Full gels can be found in Figure S5 and S6.

RNAMake generated 100 designs (RM-Tethers), containing either four or five noncanonical structural motifs each (see Methods for motif selections), to tether the H101 helix on a circularly permuted 23S rRNA to the h44 helix on the 16S rRNA (Figure 1b, Figure S3b). Of the nine diverse solutions we tested (RM-Tether 1 to 9), DNA templates for seven could be synthesized, and transformation of these DNA templates into the Squires strain allowed us to assay whether the RNAMake designs could replace wild type ribosomes deleted from growing bacteria. One of these seven constructs, RM-Tether 4, led to viable growth of bacterial colonies. DNA sequencing confirmed that these colonies harboured the correct RM-Tether 4 plasmid; and RNA electrophoresis confirmed the presence of a single dominant RNA species with the same length as Ribo-T, with no detectable products corresponding to separate 16S or 23S rRNA lengths or other cleavage products (Figure 3d). While the growth rate of this strain was low (Figure S4d), we were able to independently confirm that the ribosomes loaded on mRNA in vitro, using integrated synthesis, assembly, and translation (iSAT) in ribosome-free S150 extracts35,36. Similar to Ribo-T16, we detected 70S/monosome37 and polysomes (and no 30S or 50S subunits) by separation of iSAT-prepared RM-Tether 4 ribosomes on a sucrose gradient (see Methods) (Figure 3e). Electrophoresis of the polysome fraction confirmed that it contained an uncleaved rRNA the same size as Ribo-T (Figure 3f). In addition, SHAPE-Seq mapping on this rRNA confirmed that the RM-Tether 4 can be reverse transcribed from one ribosomal subunit to the other across both strands of the tether and highlights chemical reactivity consistent with the design, with one region of flexibility around the middle junction (Figure S5). Taken together, these data demonstrate that RNAMake-designed ribosomes with structured, chemically stable tethers can replace wild type ribosomes in vivo and more than one such ribosome can be loaded onto a single message in vitro. RNAMake obviates repeated rounds of trial and error that were previously required to achieve these design goals.

Automated improvement of small-molecule binding RNA aptamers

As a final series of tests, we evaluated whether RNAMake could solve 3D design problems whose complexity precluded prior progress even with trial and error or large-scale library selections. Small molecules can be bound and sensed by artificially selected RNA aptamers. Unfortunately, these molecules often exhibit weakened binding affinities or instability in biological environments, and additional rounds of selection to improve aptamers typically give diminishing returns38–40. By expanding RNAMake to allow design of interconnections between multiple pairs of helices (Figure 1c), we tested the hypothesis that the computational design of peripheral tertiary contacts might ‘lock’ these artificial aptamers into their bound conformation even in the absence of ligand. By reducing the number of alternative structures available in the unbound state, such locking contacts could selectively increase the free energy of the unbound state and thereby improve the free energy difference to the bound state, leading to better affinity to small molecule targets.

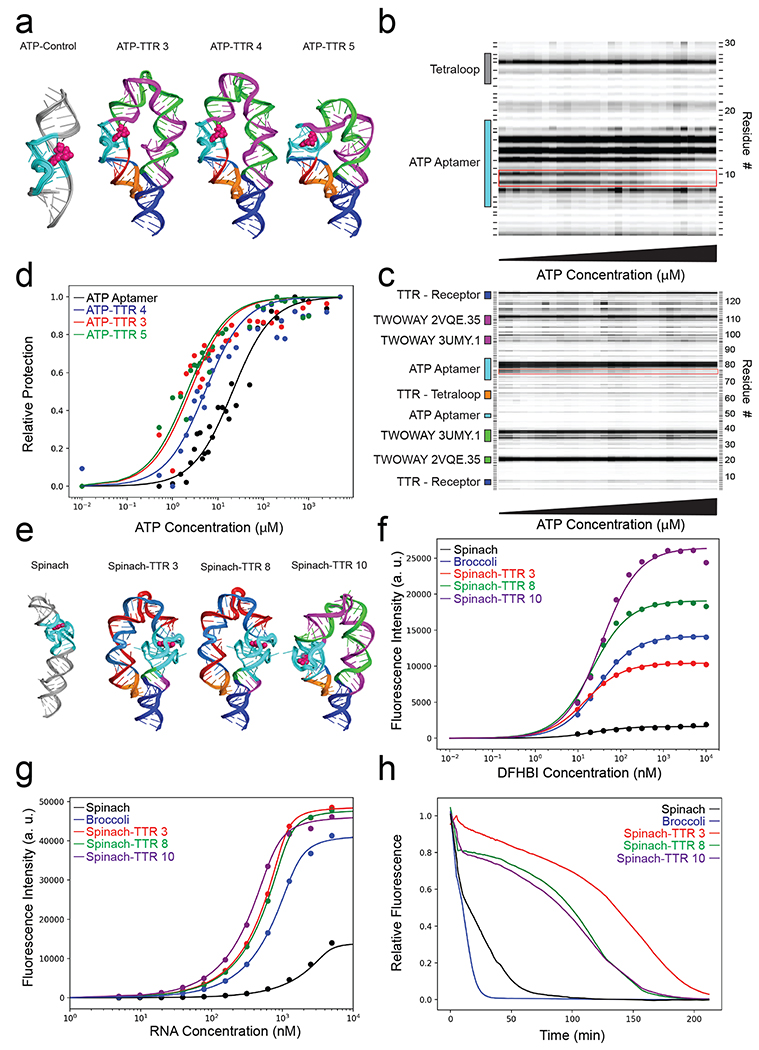

First, we sought to stabilize a classic aptamer for adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine 5′-monophosphate (ATP and AMP), which is in wide use in RNA nanotechnology but whose binding has not been appreciably improved since its discovery in 199341–45. In total, we tested 10 ATP aptamers embedded by RNAMake into scaffolds with tetraloop/receptor contacts, which we called ATP-TTR designs (Figure 4a; Figure S6; Methods describes modelling of helix flexibility used for these designs). Chemical mapping confirmed that four of these RNAs formed the TTR and also retained their ability to bind to ATP, as assessed by DMS protection of aptamer nucleotides A13 and A14 (Table S4; Figure S7). Titrations of ATP read out through chemical mapping (Table S4; Figure 4d) showed that three designs achieved better ATP dissociation constants (Kd of 1.5, 4.1, and 1.4 μM) than the isolated ATP aptamer under the same conditions (Kd = 16.2 μM), improvements by up to an order of magnitude. Three of the ATP-TTRs gave ligand-free DMS reactivity profiles in the aptamer regions similar to the ligand-bound aptamer, suggesting that they pre-form the structure needed for ATP binding rather than requiring conformational rearrangements observed in the isolated ATP aptamer (Figure 4b–c; Table S4)41. These results demonstrate that the TTR peripheral contact efficiently couples to enhance binding of ATP in the aptameric region, as desired. As a further test of this coupling, we confirmed that the Mg2+ requirements for forming the TTR was reduced in the presence compared to the absence of the small molecule ligand in these constructs (Supplemental Results and Figure S7b).

Figure 4: Stabilizing aptamers for ATP and light-up fluorophores through designer tertiary contacts.

a) 3D models of the ATP aptamer alone and ATP-TTRs 3, 4, and 5. b) DMS probing of ATP titration of the ATP aptamer, red box denotes the two adenines that become protected upon addition of ATP. c) DMS probing of ATP titration of ATP-TTR 4, red box denotes the two adenines that become protected upon addition of ATP. d) Quantified DMS protection as a function of ATP concentration for the ATP aptamer compared to ATP-TTRs 3, 4 and 5. e) The crystal structure of the Spinach aptamer bound to DFHBI (left), 3D models of Spinach-TTRs 3, 8, and 10 (right). f) Fluorescence measurements of a DFHBI titration at constant RNA concentration of Spinach, Broccoli and Spinach-TTR 3, 8 and 10. g) Fluorescence measurements of an RNA titration with constant DFHBI concentration of Spinach, Broccoli and Spinach-TTR 3, 8 and 10. h) Fluorescence in 20% lysate as compared to the construct in buffer for Spinach, Broccoli and Spinach-TTR 3, 8 and 10.

As a second test of aptamer stabilization, we assessed whether RNAMake could stabilize the Spinach RNA, which binds an analogue of the green fluorescent protein chromophore (Z)-4-(3,5-Difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene)-1,2-dimethyl-1H-imidazol-5(4H)-one (DFHBI) within a G-quadruplex. Binding to Spinach enhances the fluorescence of DFHBI by ~1,000-fold relative to unbound ligand, making this RNA useful for biological interrogations39,46, although its binding affinity, brightness, folding efficiency and biological stability remain poor even after extensive efforts to discover improvements such as the minimized Spinach and Broccoli aptamers47–50. We characterized 16 ‘Spinach-TTR’ molecules designed by RNAMake to embed the Spinach aptamer into scaffolds with tetraloop/receptor contacts (Figure 4e; Figure S8). SHAPE chemical mapping confirmed that these molecules form tetraloop-receptor contacts in 13 of 15 cases that could be tested (Figure S9 and Table S5). By carrying out fluorescence assays titrating both RNA and DFHBI concentration, we evaluated these design’s dissociation constants, brightness, and folding efficiency. Seven of the 16 Spinach-TTR designs exhibited 2-fold brighter fluorescence than the original Spinach as well as the brighter Broccoli aptamer (Figure 4f; Table S5–6; Figure S10). Two of these constructs, Spinach-TTR 3 and 8 were not only brighter but also gave higher affinity and improved folding efficiency relative to Broccoli and a minimized Spinach construct, Spinach-min (Figure 4g).

We hypothesized that these improvements to in vitro stability measures might also lead to improved stability in harsh biological environment. When the DFHBI-bound RNAs were challenged with 20% whole cell lysate extracted from the eggs of Xenopus laevis, six of the seven Spinach-TTR constructs exhibited fluorescence longer than control Spinach and Broccoli sequences (see Methods). Spinach-TTR 3 exhibited particularly high stability (Figure 4h), giving a time to half fluorescence of 131 minutes, compared to < 20 minutes for Spinach, Spinach-min, and Broccoli (Table S6; Figure S11). This same robust fluorescence of the Spinach-TTRs was observed in 20% E. coli. lysate, suggesting a general stabilization in biological environments (Figure S12). We finally sought to assess the ability of Spinach-TTR constructs to activate fluorescence in cells, using E. coli as a testbed. Six Spinach-TTR designs were cloned into a plasmid for T7 RNA polymerase-driven expression (see Materials and Methods). Each Spinach-TTR variant was able to significantly activate expression above background, and several designs exceeded the fluorescence observed for both Spinach and Broccoli in vivo (Figure S13).

Conclusions

As RNA nanotechnology seeks to create artificial molecules closer in sophistication to natural RNA molecules, designing tertiary structures as complex, asymmetric, and diverse as natural RNAs becomes an important goal. Here, we hypothesized that several distinct tasks in designing complex RNA tertiary structure might be reduced to instances of a single RNA motif pathfinding problem and developed an algorithm RNAMake to solve the pathfinding task (Supplemental Results; Table 1). For the ‘miniTTR’ nanostructure design problem, 11 of 16 molecules exhibited the correct tertiary fold in nucleotide-resolution chemical mapping and electrophoresis assays, and we achieved a crystal structure of one design that confirmed its accuracy at high resolution. For the problem of tethering E. coli 16S and 23S rRNAs into a single RNA molecule, 1 of 9 RNAMake-designed molecules replaced ribosomes in vivo and was confirmed to translate in polysomes in cell-free translation reactions. For the problem of stabilizing aptamers through ‘locking’ tertiary contacts, 3 of 11 RNAMake-designed ATP-TTR molecules achieved improved affinity to ATP compared to the starting aptamer; and 7 of 16 Spinach-TTR designs maintained their binding affinity for the DFHBI fluorophore while achieving improvements in fluorescence and folding efficiency in vitro, and instability in extracto and in vivo. In each task, RNAMake achieved its design objectives in a single round of tests involving parallel synthesis of 8 to 16 constructs, without further trial-and-error iteration.

Table 1:

RNAMake designs and component motifs generated for all 4 design problems.

| Design problem | Designs | Successful Designs | Motifs Used | Experimentally Validated Motifs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiniTTR | 16 | 11 | 23 | 20 |

| Ribosome tether | 9 | 1 | 14 | 3 |

| ATP-TTR | 10 | 3 | 16 | 6 |

| Spinach-TTR | 16 | 13 | 26 | 20 |

| All | 51 | 28 | 56* | 41* |

Some motifs were used in multiple design problems.

As RNAMake is applied to more problems, we expect its success rate to further improve. Accumulating knowledge of which structural motifs recur in successful vs failing designs may allow for empirical scoring for the modularity of each motif; inferences for some motifs, such as A-A mismatches, are already possible (Supplemental Discussion). Second, incorporation of motifs that are known to sample at least two conformations (e.g., the triple mismatch in miniTTR6 herein or kink turns) may allow improved design of such machines like the ribosome, with improving cryo-EM methods providing more detailed feedback on such distinct states18,51. Third, natural structured RNAs often contain multiple tertiary contacts and multibranched junctions and we have extended RNAMake’s pathfinding method to design such motifs (Supplementary Figure 14). Finally, we expect RNAMake’s computational design approach to be complementary to library selection and high-throughput screening methods52, especially for larger problems that require numerous noncanonical motifs. By distributing RNAMake as source code and a server, we hope to encourage these applications and extensions of computational RNA design.

METHODS

Software Availability

All software and source code used in this work are freely available for non-commercial use. RNAMake software and documentation are at https://github.com/RNAMake/RNAMake. An RNAMake server to perform scaffolding and aptamer stabilization is available at http://rnamake.stanford.edu. EteRNAbot is available at https://github.com/EteRNAgame/EteRNABot.

Sequences and Primers.

All sequences and primers used in this study can be found in Supplemental Material, in files Sequences.xlsx and Primers.xlsx, respectively.

Building the Motif Library.

To build a curated motif library of all RNA structural components, we obtained the set of non-redundant RNA crystal structures managed by the Leontis and Zirbel groups53 (version 1.45: http://rna.bgsu.edu/rna3dhub/nrlist/release/1.45). This set specifically removes redundant RNA structures that are identical to previously solved structures, such as ribosomes crystallized with different antibiotics. We processed each RNA structure to extract every motif with Dissecting the Spatial Structure of RNA (DSSR)54 with the following command:

x3dna–dssr –i file.pdb –o file_dssr.out

We manually checked each extracted motif to confirm that it was the correct type, as DSSR sometimes classifies tertiary contacts as higher-order junctions and vice-versa. For each motif collected from DSSR, we ran the X3DNA find_pair and analyze programs to determine the reference frame for the first and last base pair of each motif to allow for alignment between motifs:

find_pair file.pdb 2> /dev/null stdout | analyze stdin >& /dev/null

The naming convention for each motif involves the motif classification, the originating PDB accession code, and a unique number to distinguish from other motifs of the same type, all separated by periods. For example, TWOWAY.1GID.2, is a two-way junction from the PDB 1GID and is the third two-way junction to be found in this structure. All motifs retain their original residue numbering, chain IDs and relative position compared to their originating structure.

In addition to the motifs derived from the PDB, we also utilized the make-na web server (http://structure.usc.edu/make-na/server.html) to generate idealized helices of between 2 and 22 base pairs in length23. All motifs in these generated libraries are bundled with RNAMake and are grouped together by type (junctions, hairpins, etc.) in sqlite3 databases in the directory RNAMake/RNAMake/resources/motif_libraries/(https://github.com/RNAMake/RNAMake/tree/master/RNAMake/resources/motif_libraries_new).

Automatically Building New RNA Segments.

RNAMake seeks a path for RNA helices and noncanonical motifs that can connect two base pairs separated by a target translation and rotation. We developed a depth-first search algorithm to discover such RNA paths. The algorithm is guided by a heuristic cost function f inspired by prior manual design efforts2,25 and is composed of two terms:

| (1) |

The first term, h(path), describes how close the last base pair in the path is to the target base pair; h(path) = 0, corresponds to a perfect overlap in translation and rotation. The functional form for h(path) depends on the spatial position of each base pair’s centroid d and an orthonormal coordinate frame R defining the rotational orientation of each base pair (46):

| (2) |

Here, W(d) is:

| (3) |

Where d is measured in Angstroms. The weight W(d) reduces the importance of the current base pair and the target base pair with similar alignment when they are spatially far apart. This term conveys the intuition that aligning the two coordinate frames becomes important only as the path of the motif and helices approaches the target base pair. RNAMake readily allows for the exploration of alternative forms of the cost function terms in (2) and (3), including more standard rotationally invariant metrics to define rotation matrix differences 55 or base-pair-to-base-pair RMSDs based on quaternions56, but these were not tested in the current study.

The second term in the cost function (1) is g(path) which parameterizes the properties of the non-canonical RNA motifs and helices comprising the path at each stage of the calculation

| (4) |

where Sss is a secondary structure score for all the motifs and helices in the path. This Sss term favors longer canonical helices as well as motifs with frequently recurring base pairs, as follows. All base pairs found in the RNA motif are scored based on their relative occurrences in all high-resolution crystal structures; all unpaired residues receive a penalty, and Watson-Crick base pairs receive an additional bonus score (Table S9). Values were derived based on logarithms of the frequencies of these elements in the crystallographic database, i.e. the inverse Boltzmann approximation 57, so that that frequency of the elements in RNAMake designs was similar to what is seen in natural RNA tertiary structures. In addition to the secondary structure score, Nmotifs penalizes the total number of motifs in the path, here taken as the number of non-canonical motifs plus the number of helices (independent of helix length).

The search adds motifs and helices to the path in a depth-first manner, while the total cost function f(path) decreases, back-tracking if f(path) increases. Any solutions with h(path) less than 5, i.e., overlap at approximately nucleotide resolution between the path’s last base pair and the target base pair, are accepted into a list of final designs. The balance between g(path) and h(path) allows RNAMake to reduce the number of motif combinations considered, finding most solutions in a few seconds. For each solution, we then used EteRNAbot, a secondary structure optimization algorithm that has undergone extensive empirical tests24, to fill in helix sequences.

Proteins that are included in the coordinates supplied to RNAMake are represented as steric beads centered at the Cα atom of each amino acid. This representation allows RNAMake to avoid steric clashes with proteins, particularly for the ribosome tethering problems.

Design, synthesis and experimental testing of miniTTR constructs

RNAMake design of miniTTR constructs, in vitro synthesis, and experimental testing can be found in the supplemental methods.

Design, construction and experimental testing of ribosome tether constructs

RNAMake design of ribosome tether constructs, cloning and replacing wild type ribosome and experimental can be found in the supplemental methods.

Design, synthesis and experimental testing of aptamer-stabilizing constructs

RNAMake design of ATP and Spinach stabilized constructs, and experimental testing by RNA structure probing, fluorescence measurements, Spinach-TTR stability assay in Xenopus egg extract and in vivo Spinach aptamer testing can be found in the supplemental methods.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Furthermore, all of our chemical mapping data are available on rmdb.stanford.edu, a detailed table of the accession IDs is given in the Supplemental Material.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We thank S. Bonilla for assistance in performing native gel assays and A. Watkins for discussions about ribosome tether design. We thank the Straight lab for graciously providing Xenopus laevis whole cell lysate. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, through NIGMS MIRA R35 GM122579 (R.D.), R01 GM121487 (R.D), New Innovator Award 1DP2GM110838 (to J.B.L.), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowships GM112294 (to J.D.Y.) and GM100953 (to D.E.), P01 GM066275 (to D.H.), and R35 GM118070 (to J.S.K.), a Stanford School of Medicine Discovery Innovation Award (to R.D.), Army Research Office W911NF-16-1-0372 (to M.C.J.); National Science Foundation through MCB-1716766 (to M.C.J.), Career Award 1452441 (to J.B.L.) and Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1324585 (A.E.D); and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (to M.C.J.) and the Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Program (to M.C.J.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Guo P The emerging field of RNA nanotechnology. Nat. Nanotechnol 5, 833–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabow WW & Jaeger L RNA self-assembly and RNA nanotechnology. Acc. Chem. Res 47, 1871–1880 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leontis NB, Lescoute A & Westhof E The building blocks and motifs of RNA architecture. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 16, 279–287 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaeger L & Chworos A The architectonics of programmable RNA and DNA nanostructures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 16, 531–543 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaeger L & Leontis NB Tecto-RNA: One-Dimensional Self-Assembly through Tertiary Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 39, 2521–2524 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H et al. Crystal structure of 3WJ core revealing divalent ion-promoted thermostability and assembly of the Phi29 hexameric motor pRNA. RNA 19, 1226–1237 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weizmann Y & Andersen ES RNA nanotechnology—The knots and folds of RNA nanoparticle engineering. MRS Bull. 42, 930–935 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jasinski D, Haque F, Binzel DW & Guo P Advancement of the emerging field of RNA nanotechnology. ACS Nano 11, 1142–1164 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afonin KA et al. Computational and experimental characterization of RNA cubic nanoscaffolds. Methods 67, 256–265 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jossinet F, Ludwig TE & Westhof E Assemble: an interactive graphical tool to analyze and build RNA architectures at the 2D and 3D levels. Bioinformatics 26, 2057–2059 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wimberly BT et al. Structure of the 30S ribosomal subunit. Nature 407, 327–339 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen THD et al. The architecture of the spliceosomal U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP. Nature 523, 47–52 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miao Z et al. RNA-Puzzles Round III: 3D RNA structure prediction of five riboswitches and one ribozyme. RNA 23, 655–672 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasalean L, Baudrey S, Leontis NB & Jaeger L Controlling RNA self-assembly to form filaments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 1381–1392 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried SD, Schmied WH, Uttamapinant C & Chin JW Ribosome subunit stapling for orthogonal translation in e. coli. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 54, 12791–12794 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orelle C et al. Protein synthesis by ribosomes with tethered subunits. Nature 524, 119–124 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson ED Creating Ribo-T: (Design, Build, Test)n. ACS Synth. Biol. 4, 1173–1175 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmied WH et al. Controlling orthogonal ribosome subunit interactions enables evolution of new function. Nature 564, 444–448 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Famulok M Oligonucleotide aptamers that recognize small molecules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 9, 324–329 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porter EB, Polaski JT, Morck MM & Batey RT Recurrent RNA motifs as scaffolds for genetically encodable small-molecule biosensors. Nat. Chem. Biol 13, 295–301 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotrik M et al. Direct Selection of Fluorescence-Enhancing RNA Aptamers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 3583–3591 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montange RK & Batey RT Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biophys 37, 117–133 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macke TJ & Case DA in Molecular modeling of nucleic acids (eds. Leontis NB & SantaLucia J) 682, 379–393 (American Chemical Society, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J et al. RNA design rules from a massive open laboratory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2122–2127 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dibrov SM, McLean J, Parsons J & Hermann T Self-assembling RNA square. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6405–6408 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afonin KA et al. Multifunctional RNA nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 14, 5662–5671 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khisamutdinov EF et al. Fabrication of RNA 3D nanoprisms for loading and protection of small rnas and model drugs. Adv. Mater. Weinheim 28, 10079–10087 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bindewald E, Grunewald C, Boyle B, O’Connor M & Shapiro BA Computational strategies for the automated design of RNA nanoscale structures from building blocks using NanoTiler. J Mol Graph Model 27, 299–308 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang L & Lilley DMJ A quasi-cyclic RNA nano-scale molecular object constructed using kink turns. Nanoscale 8, 15189–15195 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu L, Chai D, Fraser ME & Zimmerly S Structural variation and uniformity among tetraloop-receptor interactions and other loop-helix interactions in RNA crystal structures. PLoS One 7, e49225 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frederiksen JK, Li N-S, Das R, Herschlag D & Piccirilli JA Metal-ion rescue revisited: biochemical detection of site-bound metal ions important for RNA folding. RNA 18, 1123–1141 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rangan P, Masquida B, Westhof E & Woodson SA Assembly of core helices and rapid tertiary folding of a small bacterial group I ribozyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1574–1579 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiore JL & Nesbitt DJ An RNA folding motif: GNRA tetraloop-receptor interactions. Q Rev Biophys 46, 223–264 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein DJ, Schmeing TM, Moore PB & Steitz TA The kink-turn: a new RNA secondary structure motif. EMBO J. 20, 4214–4221 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jewett MC, Fritz BR, Timmerman LE & Church GM In vitro integration of ribosomal RNA synthesis, ribosome assembly, and translation. Mol. Syst. Biol 9, 678 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fritz BR, Jamil OK & Jewett MC Implications of macromolecular crowding and reducing conditions for in vitro ribosome construction. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 4774–4784 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Underwood KA, Swartz JR & Puglisi JD Quantitative polysome analysis identifies limitations in bacterial cell-free protein synthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng 91, 425–435 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carothers JM, Oestreich SC & Szostak JW Aptamers selected for higher-affinity binding are not more specific for the target ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc 128, 7929–7937 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paige JS, Wu KY & Jaffrey SR RNA mimics of green fluorescent protein. Science 333, 642–646 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellington AD & Szostak JW In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang F, Kumar RA, Jones RA & Patel DJ Structural basis of RNA folding and recognition in an AMP-RNA aptamer complex. Nature 382, 183–186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Z & Szostak JW Evolution of aptamers with a new specificity and new secondary structures from an ATP aptamer. RNA 9, 1456–1463 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sassanfar M & Szostak JW An RNA motif that binds ATP. Nature 364, 550–553 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sazani PL, Larralde R & Szostak JW A small aptamer with strong and specific recognition of the triphosphate of ATP. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 8370–8371 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geary C, Chworos A, Verzemnieks E, Voss NR & Jaeger L Composing RNA Nanostructures from a Syntax of RNA Structural Modules. Nano Lett. 17, 7095–7101 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kellenberger CA, Chen C, Whiteley AT, Portnoy DA & Hammond MC RNA-Based Fluorescent Biosensors for Live Cell Imaging of Second Messenger Cyclic di-AMP. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 6432–6435 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strack RL, Disney MD & Jaffrey SR A superfolding Spinach2 reveals the dynamic nature of trinucleotide repeat-containing RNA. Nat. Methods 10, 1219–1224 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Filonov GS, Moon JD, Svensen N & Jaffrey SR Broccoli: rapid selection of an RNA mimic of green fluorescent protein by fluorescence-based selection and directed evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 16299–16308 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ketterer S, Fuchs D, Weber W & Meier M Systematic reconstruction of binding and stability landscapes of the fluorogenic aptamer spinach. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 9564–9572 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song W, Strack RL, Svensen N & Jaffrey SR Plug-and-play fluorophores extend the spectral properties of Spinach. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 1198–1201 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi X, Huang L, Lilley DMJ, Harbury PB & Herschlag D The solution structural ensembles of RNA kink-turn motifs and their protein complexes. Nat. Chem. Biol 12, 146–152 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buenrostro JD et al. Quantitative analysis of RNA-protein interactions on a massively parallel array reveals biophysical and evolutionary landscapes. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 562–568 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrov AI, Zirbel CL & Leontis NB Automated classification of RNA 3D motifs and the RNA 3D Motif Atlas. RNA 19, 1327–1340 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu X-J, Bussemaker HJ & Olson WK DSSR: an integrated software tool for dissecting the spatial structure of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e142 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huynh DQ Metrics for 3D rotations: comparison and analysis. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 35, 155–164 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karney CFF Quaternions in molecular modeling. J Mol Graph Model 25, 595–604 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finkelstein AV, Badretdinov AYa & Gutin AM Why do protein architectures have Boltzmann-like statistics? Proteins 23, 142–150 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kladwang W, Cordero P & Das R A mutate-and-map strategy accurately infers the base pairs of a 35-nucleotide model RNA. RNA 17, 522–534 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Furthermore, all of our chemical mapping data are available on rmdb.stanford.edu, a detailed table of the accession IDs is given in the Supplemental Material.