Abstract

Serum amyloid A (SAA) is both an amyloidogenic protein of amyloid A amyloidosis and an acute phase protein in most animal species. Although SAA isoforms, such as SAA1, 2, 3, and 4, have been identified in cattle, their biological functions are not completely understood. Previous studies using mice indicated that SAA3 mRNA expression increased by stimulation with Escherichia coli and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in colonic epithelial cells, and subsequently the SAA3 protein enhanced the expression of mucin2 (MUC2) mRNA, which is the major component of the colonic mucus layer. These results suggest that SAA3 plays a role in host innate immunity against bacterial infection in the intestine. In this study, a novel anti-bovine SAA3 monoclonal antibody was produced and SAA3 expression levels in bovine epithelia were examined in vitro and in vivo using real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC). SAA3 mRNA expression, but not that of SAA1, was enhanced by LPS stimulus in bovine small intestinal and mammary glandular epithelial cells in vitro. Moreover, in bovine epithelia (small intestine, mammary gland, lung, and uterus) obtained from four Holstein dairy cows from a slaughterhouse, SAA3 mRNA expression was higher than that of SAA1. Furthermore, using IHC, SAA3 protein expression was observed in bovine epithelia, whereas SAA1 protein was not. These results suggest that in cattle, SAA3 plays an immunological role against bacterial infection in epithelial tissues, including the small intestine, mammary gland, lung, and uterus.

Keywords: cattle, epithelium, immunohistochemistry, real-time PCR, serum amyloid A3

Amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis is a common fatal disease in animals, which is characterized by the deposition of insoluble AA amyloid in systemic tissues [19]. In bovine AA amyloidosis, AA amyloid deposits can be observed in systemic organs, including the edible skeletal muscles [20, 30], and severe AA amyloid deposits are typically found in the kidney; these cause nephrosis accompanied by diarrhea and edema [5]. Serum AA (SAA) is the precursor protein of AA amyloid and is produced in reaction to chronic infection or chronic inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile inflammatory arthritis in humans [21]. Thus, plasma concentration of SAA has been developed as a diagnostic marker of infection and inflammation in mammals including humans [3]. Multiple SAA isoforms have been identified through amino acid sequence analysis, including SAA1, 2, 3, and 4, in several mammalian species [29]. SAA1 and SAA2 are predominantly produced in the liver and represent the main circulating isoforms in the plasma [29]. The plasma concentration of SAAs, mainly SAA1, markedly increases by up to 1,000-fold during inflammation [29]. In contrast, SAA3 is mainly expressed by extrahepatic tissues such as the intestines in mice [16] and mammary glands in cattle [15]. Previous studies have shown that SAA3 expression increases in mouse colon epithelia in the presence of microbiota [23], and that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) strongly induces SAA3 mRNA expression, but not that of SAA1/2 [23, 24]. LPS is a major component in the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli. Moreover, recombinant SAA3 protein increases mucin2 (MUC2) mRNA expression in murine colonic epithelial CMT-93 cells [24]. MUC2 is the major component of the mucus layer in the colon that acts as a physical barrier for epithelial cells against pathogens [11]. These results suggest that SAA3 contributes to innate immunity in the murine colon.

SAA isoforms have been identified in cattle, and bovine SAA3 is regulated differently from other SAA isoforms with respect to the expression site and stimulus types [13]. SAA3 mRNA has been detected in bovine mammary glands using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and may be involved in pathogen defense in the mammary gland [15, 18]. However, the biological function and expression of SAA3 in other epithelia in cattle are unclear.

In this study, to investigate whether bovine SAA3 mRNA expression is enhanced by bacterial LPS, real-time PCR was performed on bovine small intestinal epithelial (BIE) [17] and mammary glandular epithelial MAC-T [9] cells. SAA1 and SAA3 mRNA and protein levels were also measured using real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC) in epithelial tissues (e.g., the small intestine, mammary gland, lung, and uterus) and livers of healthy cows.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monoclonal antibodies

The monoclonal antibody 25BF12 [27] was used to detect bovine SAA1 protein. A novel monoclonal antibody against bovine SAA3 protein was produced as follows: Five-week-old female BALB/c inbred mice weighing 14–19 g (Japan SLC, Hamamatsu, Japan) were immunized intraperitoneally with 20 µg of synthesized bovine SAA3 peptide containing amino acid residues 92 to 107 (KGMTRDQVREDSKADQ, GenBank accession no. AAM11538) (Fig. 1A) and conjugated with KLH, with complete Freund’s adjuvant (Wako, Osaka, Japan). Immunization was boosted with the same antigens with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Wako) on days 14 and 28 after the first immunization. Mice were sacrificed 3 or 4 days after the last booster, and the spleens were excised aseptically. The splenic cells were fused with P3-X63-Ag8-U1 myeloma [31] using polyethylene glycol 1500 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and the fused cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM, 044-29765, Wako) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, lot number A15-701, PAA Laboratories GmbH, Pasching, Austria) and Hat supplement (091680849, MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA). Hybridomas producing specific antibodies were selected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described below. The hybridomas obtained were subcloned twice using the limiting dilution method. All procedures performed in the animal experiments were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and practice. The experimental design was approved by the Gifu University Animal Care and Use Committee (approval numbers 10063 and 17081).

Fig. 1.

Production of anti-bovine serum amyloid A3 monoclonal antibody. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequence of bovine serum amyloid A1 (SAA1, GenBank accession number AAI09788) and SAA3 (AAM11538). Red box shows the sequence of synthetic peptide (KGMTRDQVREDSDADQ) for immunization. (B) Detection of recombinant bovine SAA1 and SAA3 using monoclonal antibody in western blot analysis. Monoclonal antibodies 25BF12 and 231G7 detected only recombinant bovine SAA1 and SAA3 protein, respectively. Anti-Xpress antibody reacted with both SAA1 and SAA3 recombinant proteins, because Xpress is the epitope tag protein for expression of recombinant protein.

Production of anti-bovine SAA3 antibody in mouse ascetic fluids was performed by BioGate (Gifu, Japan) using a hybridoma obtained in the current study.

ELISA

Synthesized bovine SAA3 peptide (10 ng/well) without KLH in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used to coat each well of the 96-well plastic plates (MaxiSorp, Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) and incubated overnight at 4°C. After adsorption, the wells were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. Fifty microliters of culture supernatant of hybridoma was added as primary antibodies and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. After washing three times with PBST, each well was treated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. After washing four times with PBST, antigen-antibody complexes were detected by adding 50 µl substrate solution, which contained 50 mM citric acid, 0.04% hydrogen peroxide, and 120 µg/ml of 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethyl-benzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) di-ammonium salt (Wako), pH 4.0. After incubation for 15 min at room temperature, the developed green color was measured at 405 nm using an ELISA plate reader MS-UV (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

Expression of recombinant bovine SAA

Total RNA was extracted from normal bovine kidney using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), the genes of bovine SAA1 and SAA3 were amplified with primers, bSAA1 F (5′-CCCCCCGAGCTCCAGTGGATGTCCTTCTTTGGT-3′) and bSAA1 R (5′-AAACGGTACCTCAGTACTTGTCAGGCAGGCC-3′), bSAA3 F (5′-CCCCCCGAGCTCCAGAGATGGGGGACATTC-3′) and bSAA3 R (5′-AAACGGTACCTCAGTACTTGTCAGGCAGGCC-3′) using a Titan One Tube/RT-PCR Kit (Roche Diagnostics). The amplified PCR fragment of bovine SAA1 and SAA3 were digested with Sac I and Kpn I restriction enzymes (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and cloned into the Sac I and Kpn I sites of a pRSET A expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then transformed into E. coli DH5α (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan). Cloned plasmids were confirmed through sequencing and then purified. Purified plasmid DNA was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS (Invitrogen). Initially, 3–5 ml cultures were grown overnight at 37°C, and 1 ml of the culture fluid was transferred into 100 ml of LB medium, and cultured at 37°C. When the absorbance of culture fluid reached an OD600 of 0.4–0.6, 1 mM isopropylthio-β-D-galactoside was added to induce SAA expression and incubated at 37°C for 4–6 hr. The cells were collected through centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C using an R14A rotor with a himac CR20GII centrifuge (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of 0.02 M sodium phosphate and 0.5 M NaCl and treated with 100 µl of 10 mg/ml lysozyme and 1 M PMSF, 10% sodium deoxycholate, 50 µl of 1M MgCl2, and 10 mg/ml DNase I. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, the suspension was centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C using an RPR20 rotor with a himac CF 16RX (Hitachi). The supernatant was purified using Ni2+ affinity chromatography and a Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein was eluted from Ni2+-column with imidazole elution buffer (0.02 M sodium phosphate, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.05–0.5 M imidazole, pH 7.0). Fractions were collected and their purities were checked using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamid gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blot analysis. Next, purified fractions were dialyzed against 0.02 M sodium phosphate and 0.5 M NaCl. The dialyzed solution was concentrated using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters Ultracel-3K (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and used as recombinant bovine SAAs for western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

Recombinant bovine SAA1 and SAA3 were dissolved in SDS-sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 6% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, and bromophenol blue) and boiled for 5 min before electrophoresis. These samples were loaded onto a 10% or 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamid gel and electrophoresed. Protein was transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Cork, Ireland), blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBST, and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with the primary antibodies, anti-bovine SAA1 25BF12 [27], anti-bovine SAA3 231G7 (produced in this study), and anti-Xpress antibody (R91025, Invitrogen), in 1% nonfat milk in PBST for 1 hr at room temperature. After washing three times with PBST, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (GE Healthcare) in 1% nonfat milk in PBST for 1 hr at room temperature. After further washing thrice, the peroxidase activity was detected using a Pierce ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and visualized using an LAS4000mini (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Cells

BIE cells [17], which were immortalized by the simian virus 40 large T antigen (SV40 T) gene, were kindly provided by Dr. Aso (Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan) and maintained in DMEM (044-29765, Wako) containing 4,500 mg/l glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (15140-122, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), and 10% FBS. SV40 T-immortalized MAC-T cells [9] were kindly provided by Dr. Roh (Tohoku University) and maintained in DMEM (041-29775, Wako) containing 1,000 mg/l glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 10% FBS, 10 mg/ml insulin solution from bovine pancreas (10516, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 10 mg/ml hydrocortisone (H0888, Sigma). MAC-T cells are known to secret α- and β-casein [9], indicating that MAC-T cells are derived from the mammary glandular epithelium.

Tissue samples

Samples of epithelial tissues (e.g., the small intestine, mammary gland, lung, and uterus) and livers were obtained from four Holstein dairy cows aged less than 24 months housed at a slaughterhouse. The animals used in this study were randomly chosen by veterinarians and were clinically healthy. Tissue samples were collected within 4 hr after slaughter, rinsed with sterilized PBS, and stored in RNAlater Stabilization Solution (1504001, Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) on ice for RNA extraction, or fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and then embedded in paraffin for IHC.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

BIE and MAC-T cells were seeded in 6-well plates at densities ranging from 4–7 × 105 cells and incubated for 15 ± 1 hr before experiments. After incubation, the cells were rinsed with DMEM without FBS and then treated with 0–100 µg/ml LPS from E. coli O111:B4 (L2630, Sigma) in DMEM without FBS at 37°C for 2 hr. The cells on the plates were collected, washed with PBS, and total RNA was immediately extracted from the cells using the RNeasy Mini kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Thirty milligrams each of mucosal epithelial tissue samples (small intestine, mammary gland, lung, and uterus) and liver were homogenized with 600 µl of RLT buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol from the RNeasy Mini Kit by using Multi-Beads Shocker (Yasui Kikai, Osaka, Japan), and the total RNA was extracted as described above.

The RNA extracted from cell lines and tissue samples was quantified using a GeneQuant 100 spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare) and stored at −80°C until use. Contaminating DNA was removed with DNase I (18068-015, Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (RR036A, Takara, Kusatsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR of cDNA was performed in 48-well plates using 300 nmol each of forward and reverse primers, 1xFast SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (4385612, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and 10 ng of the cDNA synthesized from cell lines or tissues. Thermal cycling conditions were 20 sec at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Data were collected using a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). To measure mRNA expression, specific primers for SAA1, SAA3, and β-actin were used [7] (Table 1). SAA1 primers were designed based on the sequence from the GenBank accession no. BC109787. Results were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin, and fold changes relative to controls were determined using the ΔΔCt method [32]. For verification of specific amplification, melting-curve analysis of amplification products was performed at the end of each PCR reaction. All experiments were replicated at least three times.

Table 1. Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR.

Immunohistochemistry

Collected tissue samples (small intestine, mammary gland, lung, uterus, and liver) were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for IHC examination. Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were cut into 2 µm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For antigen retrieval IHC, deparaffinized sections were processed by steam/heat treatment using autoclave. Sections were washed with PBS, treated with 2.5% bovine serum albumin, and then immunohistochemically stained with HRP Mouse EnVision + Single Reagents (K4001, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) using anti-SAA1 monoclonal antibody 25BF12 (1:400) [27] or anti-SAA3 monoclonal antibody 231G7 (1:2,000) produced in this study. For negative controls, the primary antibody was omitted.

Statistical analysis

Data was collected from at least three independent experiments, with averages expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and tested for significant differences using unpaired t-test. All P-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Production of anti-bovine SAA3 monoclonal antibody

Specificity of a novel monoclonal antibody, 231G7, against bovine SAA3 was confirmed by ELISA using the synthesized bovine SAA3 peptide (data not shown) and through western blot analysis using the recombinant bovine SAA3 protein (Fig. 1B).

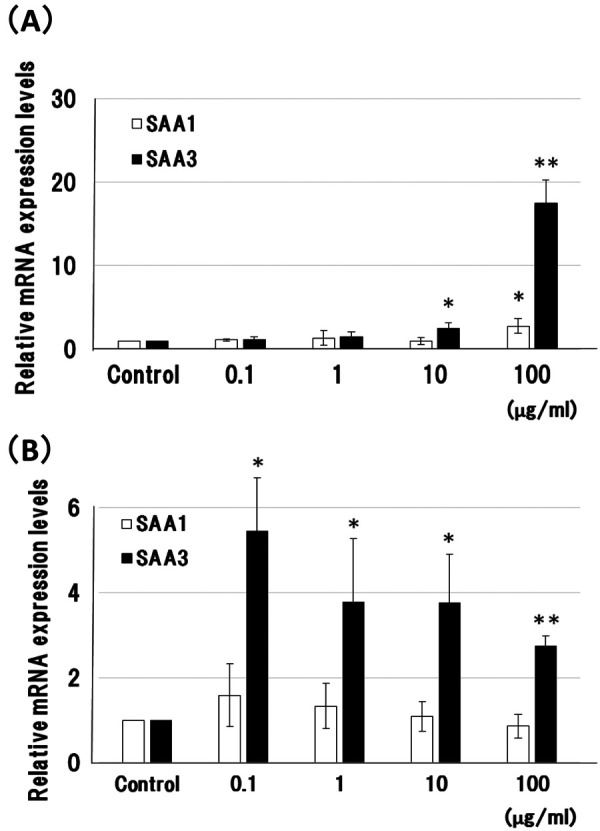

mRNA expression of SAA1 and SAA3 in BIE and MAC-T cells is stimulated by LPS

SAA3 mRNA expression in BIE cells was enhanced to a greater extent than that of SAA1 by higher concentrations of LPS (10 and 100 µg/ml; Fig. 2A). In MAC-T cells, SAA3 mRNA expression was enhanced by LPS, with smaller increases at higher LPS concentrations (Fig. 2B). In contrast, SAA1 mRNA expression was not enhanced by LPS (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of serum amyloid A1 and A3 mRNA expression in bovine small intestinal and mammary epithelial cells, induced by lipopolysaccharide. (A) Bovine small intestinal epithelial (BIE) cells and (B) mammary epithelial MAC-T cells were incubated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (0–100 µg/ml) for 2 hr at 37°C. Relative expression levels of serum amyloid A1 (SAA1) and SAA3 mRNA were normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin, and compared with a 0 µg/ml LPS control. Data are the mean values of three independent observations with standard deviations represented by vertical bars. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared to the control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

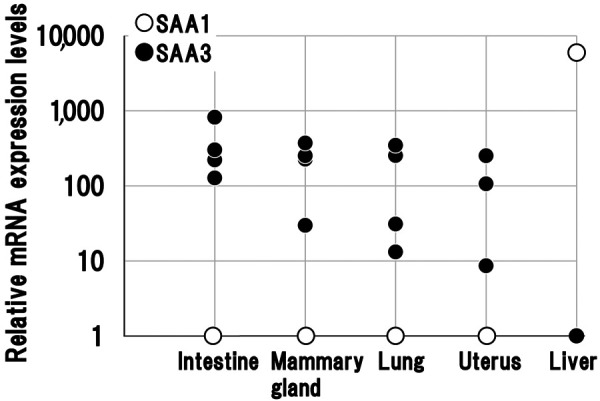

mRNA expression of SAA1 and SAA3 in mucosal epithelial tissues of cows

SAA3 mRNA expression was higher than that of SAA1 in all mucosal epithelial tissues (small intestine, mammary gland, lung, and uterus). In contrast, SAA1 mRNA expression was significantly higher than that of SAA3 in liver (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Serum amyloid A3 mRNA expression is higher than serum amyloid A1 expression in mucosal epithelial tissues, but not in the liver of cows. Relative expression of serum amyloid A1 (SAA1) and SAA3 mRNA was normalized to that of the housekeeping gene β-actin and compared with SAA1 or SAA3. Epithelial tissues were obtained from four cows and liver from one cow.

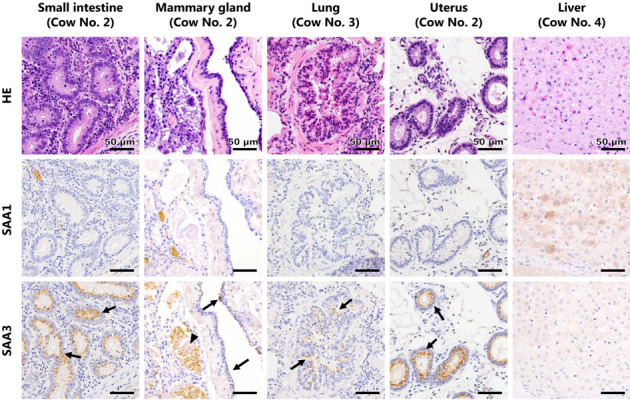

Protein expression of SAA1 and SAA3 in mucosal epithelial tissues of cows

Immunohistochemically, SAA3, but not SAA1, was detected in the mucosal epithelia of the small intestine, lactiferous ducts of the mammary gland, bronchiole of the lung, and endometrium of the uterus (Fig. 4). In the mammary gland, positive reaction with anti-SAA3 monoclonal antibody was also detected in milk (Fig. 4). In cow No. 2, positive reactions with anti-SAA3 monoclonal antibody in each epithelium were observed more frequently than those in other cows and SAA1 protein was detected in the blood of epithelial tissues (data not shown) unlike in the other cows. In contrast to epithelial tissues, hepatocytes in the livers of all cows were strongly stained with the anti-SAA1 monoclonal antibody, but weakly stained with the anti-SAA3 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Histological and immunohistochemical features of each organ. Each row shows the image of hematoxylin and eosin, anti-SAA1 immunohistochemistry, and anti-SAA3 immunohistochemistry of serial sections. In the small intestine, mammary gland, lung, and uterus, vesicular positive reactions for SAA3 were observed in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells (arrows), but not for SAA1. In the lung, positive reactions for SAA3 were observed in the bronchiolar epithelia, but not in the alveolar epithelia. In the mammary gland, positive reaction for SAA3 was also detected in milk (arrow head). Hepatocytes were strongly positive for SAA1, but weakly positive for SAA3.

DISCUSSION

A previous study showed that mRNA expression of mouse SAA3 is induced by LPS in a dose-dependent manner in mouse colonic epithelial CMT-93 cells, while mouse SAA1/2 mRNA expression is not influenced [24]. We found that SAA regulation in cows appears to be similar to that in mice. We demonstrated that SAA3 mRNA expression was enhanced by LPS in BIE and MAC-T cells, whereas SAA1 mRNA expression was not affected, except for BIE cells at the highest LPS concentration (Fig. 2A). SAA3 mRNA expression was enhanced most strongly by high LPS concentrations in BIE cells, but most strongly by low concentrations in MAC-T cells. Larson et al. [13] demonstrated by ELISA that LPS at low concentration (0.1 µg/ml) significantly stimulates mammary SAA3 production in MAC-T cells. These results suggest that mammary epithelial MAC-T cells are more sensitive against LPS than BIE cells. There are substantial differences in LPS response between primary bovine mammary epithelial (BME) cells and the immortalized MAC-T cells derived from them [26]. Although the reasons for the discrepancies between primary BME cells and immortalized MAC-T cells are unclear, it may be related to the immortalization process for MAC-T cells. Immortalized cell lines often have altered phenotypes and functions compared to parental cells [8, 14, 25]. Results in this study (Fig. 2) and previous studies [6, 13, 26] indicate that reactions to LPS in MAC-T cells are different from those in BIE cells, and it may be due to the cellular characteristics of MAC-T cells. To further clarify the response to LPS in mammary epithelial cells, additional investigations using primary BME cells with lower LPS concentrations are needed.

Kiku et al. [12] investigated the gene expression profile of primary BME cells stimulated with lipoteichoic acid (LTA), a major cell component of gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, which are found on body surfaces as indigenous commensal bacteria. However, SAA3 is not one of the top twenty upregulated genes in primary BME cells stimulated with LTA [12]. Bovine endometrial epithelial cells stimulated with E. coli showed significantly increased SAA3 mRNA expression [1]. Results in this study (Fig. 2) and previous studies [1, 12] indicate that SAA3 mRNA expression may be predominantly induced by gram-negative bacterial infection in bovine epithelial cells. To confirm the relation between SAA3 and innate immunity, it is necessary to investigate whether SAA3 stimulates the expression of genes involved in innate immunity and antibacterial polypeptide production such as Toll-like receptor 4, transcription factor NF-κB, MUC2, and β-defensins in bovine epithelial cells. Moreover, it could be possible that SAA3 is an innate immunity effector rather than a regulator.

Using a novel anti-bovine SAA3 monoclonal antibody, 231G7, SAA3 protein in the mucosal epithelial tissues and milk of the mammary gland were detected using IHC. Mammary SAA3 may be secreted from BME cells [15] and synthesized within mammary epithelial cells and those lining the gland cistern [4]. In cattle, SAA3 expression has been previously demonstrated in the mammary gland [15] and high concentrations of SAA3 protein have been detected in colostrum [15, 22] and mastitic milk [10]. The results obtained in this study (Fig. 4) are consistent with these previous observations.

In cow No. 2, an increase in SAA3-positive area was observed in each epithelium and SAA1 was detected in the blood of epithelial tissues, unlike in the other cows. SAA1 plasma concentration increases with inflammation; therefore, it is conceivable that cow No. 2 may have had systemic inflammation and that SAA3 protein expression was upregulated by local stimulants in mucosal epithelial cells. Indeed, previous studies have indicated that increases in SAA3 in milk are due to bacterial infections and can be used as a biomarker for bovine mastitis [2, 10, 28].

Collectively, the results obtained in the current study suggest that SAA3 is expressed in the mucosal epithelial tissues of cows. This expression might be a primary response of the innate immune system, involving host defense, especially against gram-negative bacterial infection.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Hisashi Aso and Dr. Sanggun Roh (Tohoku University, Japan) for providing BIE and MAC-T cells, respectively. This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16H05027 and the Grant for Joint Research Program of the Research Center for Zoonosis Control, Hokkaido University, from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chapwanya A., Meade K. G., Doherty M. L., Callanan J. J., O’Farrelly C.2013. Endometrial epithelial cells are potent producers of tracheal antimicrobial peptide and serum amyloid A3 gene expression in response to E. coli stimulation. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 151: 157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domènech A., Parés S., Bach A., Arís A.2014. Mammary serum amyloid A3 activates involution of the mammary gland in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 97: 7595–7605. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckersall P. D., Bell R.2010. Acute phase proteins: Biomarkers of infection and inflammation in veterinary medicine. Vet. J. 185: 23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckersall P. D., Young F. J., Nolan A. M., Knight C. H., McComb C., Waterston M. M., Hogarth C. J., Scott E. M., Fitzpatrick J. L.2006. Acute phase proteins in bovine milk in an experimental model of Staphylococcus aureus subclinical mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 89: 1488–1501. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72216-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elitok O. M., Elitok B., Unver O.2008. Renal amyloidosis in cattle with inflammatory diseases. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 22: 450–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan W. J., Li H. P., Zhu H. S., Sui S. P., Chen P. G., Deng Y., Sui T. M., Wang Y. Y.2016. NF-κB is involved in the LPS-mediated proliferation and apoptosis of MAC-T epithelial cells as part of the subacute ruminal acidosis response in cows. Biotechnol. Lett. 38: 1839–1849. doi: 10.1007/s10529-016-2178-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green B. B., Kerr D. E.2014. Epigenetic contribution to individual variation in response to lipopolysaccharide in bovine dermal fibroblasts. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 157: 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas C., Aicher W. K., Dinkel A., Peter H. H., Eibel H.1997. Characterization of SV40T antigen immortalized human synovial fibroblasts: maintained expression patterns of EGR-1, HLA-DR and some surface receptors. Rheumatol. Int. 16: 241–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01375656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huynh H. T., Robitaille G., Turner J. D.1991. Establishment of bovine mammary epithelial cells (MAC-T): an in vitro model for bovine lactation. Exp. Cell Res. 197: 191–199. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90422-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen S., Niewold T. A., Kornalijnslijper E., Toussaint M. J. M., Gruys E.2005. Kinetics of local and systemic isoforms of serum amyloid A in bovine mastitic milk. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 104: 21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansson M. E. V., Phillipson M., Petersson J., Velcich A., Holm L., Hansson G. C.2008. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 15064–15069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803124105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiku Y., Nagasawa Y., Tanabe F., Sugawara K., Watanabe A., Hata E., Ozawa T., Nakajima K. I., Arai T., Hayashi T.2016. The cell wall component lipoteichoic acid of Staphylococcus aureus induces chemokine gene expression in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 78: 1505–1510. doi: 10.1292/jvms.15-0706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson M. A., Weber A., Weber A. T., McDonald T. L.2005. Differential expression and secretion of bovine serum amyloid A3 (SAA3) by mammary epithelial cells stimulated with prolactin or lipopolysaccharide. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 107: 255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maqsood M. I., Matin M. M., Bahrami A. R., Ghasroldasht M. M.2013. Immortality of cell lines: challenges and advantages of establishment. Cell Biol. Int. 37: 1038–1045. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald T. L., Larson M. A., Mack D. R., Weber A.2001. Elevated extrahepatic expression and secretion of mammary-associated serum amyloid A 3 (M-SAA3) into colostrum. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 83: 203–211. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(01)00380-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meek R. L., Benditt E. P.1986. Amyloid A gene family expression in different mouse tissues. J. Exp. Med. 164: 2006–2017. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.6.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazawa K., Hondo T., Kanaya T., Tanaka S., Takakura I., Itani W., Rose M. T., Kitazawa H., Yamaguchi T., Aso H.2010. Characterization of newly established bovine intestinal epithelial cell line. Histochem. Cell Biol. 133: 125–134. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0648-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molenaar A. J., Harris D. P., Rajan G. H., Pearson M. L., Callaghan M. R., Sommer L., Farr V. C., Oden K. E., Miles M. C., Petrova R. S., Good L. L., Singh K., McLaren R. D., Prosser C. G., Kim K. S., Wieliczko R. J., Dines M. H., Johannessen K. M., Grigor M. R., Davis S. R., Stelwagen K.2009. The acute-phase protein serum amyloid A3 is expressed in the bovine mammary gland and plays a role in host defence. Biomarkers 14: 26–37. doi: 10.1080/13547500902730714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami T., Inoshima Y., Ishiguro N.2015. Systemic AA amyloidosis as a prion-like disorder. Virus Res. 207: 76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami T., Inoshima Y., Kobayashi Y., Matsui T., Inokuma H., Ishiguro N.2012. Atypical AA amyloid deposits in bovine AA amyloidosis. Amyloid 19: 15–20. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.637145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obici L., Merlini G.2012. AA amyloidosis: basic knowledge, unmet needs and future treatments. Swiss Med. Wkly. 142: w13580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orro T., Jacobsen S., LePage J. P., Niewold T., Alasuutari S., Soveri T.2008. Temporal changes in serum concentrations of acute phase proteins in newborn dairy calves. Vet. J. 176: 182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reigstad C. S., Lundén G. Ö., Felin J., Bäckhed F.2009. Regulation of serum amyloid A3 (SAA3) in mouse colonic epithelium and adipose tissue by the intestinal microbiota. PLoS One 4: e5842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shigemura H., Ishiguro N., Inoshima Y.2014. Up-regulation of MUC2 mucin expression by serum amyloid A3 protein in mouse colonic epithelial cells. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 76: 985–991. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song Y., Zheng J.2007. Establishment of a functional ovine fetoplacental artery endothelial cell line with a prolonged life span. Biol. Reprod. 76: 29–35. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.055921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strandberg Y., Gray C., Vuocolo T., Donaldson L., Broadway M., Tellam R.2005. Lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acid induce different innate immune responses in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Cytokine 31: 72–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taira Y., Inoshima Y., Ishiguro N., Murakami T., Matsui T.2009. Isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against bovine serum amyloid A1 protein. Amyloid 16: 215–220. doi: 10.3109/13506120903421595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas F. C., Waterston M., Hastie P., Parkin T., Haining H., Eckersall P. D.2015. The major acute phase proteins of bovine milk in a commercial dairy herd. BMC Vet. Res. 11: 207. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0533-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uhlar C. M., Whitehead A. S.1999. Serum amyloid A, the major vertebrate acute-phase reactant. Eur. J. Biochem. 265: 501–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada M., Kotani Y., Nakamura K., Kobayashi Y., Horiuchi N., Doi T., Suzuki S., Sato N., Kanno T., Matsui T.2006. Immunohistochemical distribution of amyloid deposits in 25 cows diagnosed with systemic AA amyloidosis. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 68: 725–729. doi: 10.1292/jvms.68.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yelton D. E., Diamond B. A., Kwan S. P., Scharff M. D.1978. Fusion of mouse myeloma and spleen cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 81: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan J. S., Reed A., Chen F., Stewart C. N., Jr.2006. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinformatics 7: 85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]