Abstract

Cryptosporidium is an obligate intracellular parasite which can cause fatal diarrheal disease in exotic animals. Sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps), hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris), chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera), and common leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) are popular exotic animals commonly sold in pet shops in Japan. We herein investigated the species and subtypes of Cryptosporidium in these animals. Cryptosporidium fayeri was detected in a sugar glider in a Japanese animal hospital. Sequence analyses of the 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60) gene revealed that C. fayeri belonged to subtype family IVh (IVhA13G2T1), which was proposed to be a new subtype. This is the first study to report C. fayeri infection in a sugar glider. In other animals, the Cryptosporidium horse genotype, C. ubiquitum, and C. varanii were detected in two four-toed hedgehogs (A. albiventris), a chinchilla (C. lanigera), and common leopard gecko (E. macularius), respectively. The gp60 subtypes identified were VIbA13 of the horse genotype and XIId of C. ubiquitum. The present results revealed that potentially zoonotic Cryptosporidium is widespread in exotic animals in Japan.

Keywords: Exotic pet, Petaurus breviceps, Cryptosporidium fayeri

Highlights

-

•

Cryptosporidium was detected from ill exotic pet animals in Japan.

-

•

Cryptosporidium fayeri was detected for the first time from a sugar glider.

-

•

The new 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60) subtype family IVh was detected from Cryptosporidium fayeri.

1. Introduction

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan parasite that causes severe diarrhea and is found in mammals, reptiles, birds, fish, and various vertebrates (Fayer, 2010). Cryptosporidiosis in exotic animals is sometimes fatal in young animals and, thus, causes economic losses to pet shops and breeders (Dellarupe et al., 2016). Therefore, the impact of infections caused by Cryptosporidium spp. and their zoonotic potential are of importance.

Sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps), hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris), chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera), and common leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) are exotic animals commonly sold in pet shops in Japan. The sugar glider is a mammal that is classified as a marsupial and belongs to the order Diprotodontia. They are omnivorous, live on trees, and form a flock of females and one male. Cryptosporidium fayeri has been detected in marsupials, including eastern grey kangaroos, yellow-footed rock wallabies, western-barred bandicoots, and koalas (Ryan et al., 2008), which generally live on the ground, except for koalas. C. fayeri is typically asymptomatic in adult animals (Power et al., 2005); although the pathogenicity of C. fayeri is currently remains unclear because of the difficulties associated with conducting wild animal surveys. C. fayeri infection has been reported in immunocompetent humans and causes prolonged gastrointestinal illness (Waldron et al., 2010).

In the present study, Cryptosporidium fayeri was detected in the sugar glider with diarrhea, and it was identified at the subtype levels using molecular techniques. Cryptosporidium spp. were also found in two hedgehogs, a common leopard gecko, and chinchilla that exhibited similar digestive symptoms to the sugar glider, and these isolates were also molecularly identified. The results of the present study provide epidemic information on cryptosporidiosis in exotic animals in Japan.

2. Materials and methods

Eleven exotic animals (two sugar gliders, four hedgehogs, two chinchillas, and three common leopard geckos) that were brought to the hospital between August and December 2017 were examined in the present study. Details on these animals are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Information of exotic animals surveyed in this study.

| Animals | Age | Body condition score | Observation | Pet shop locality | Kinyoun acid-fast staining | Results of RealPCR™ Panels | PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petaurus brevicep (Sugar glider) | 3 month | 2 | Diarrhea | Kyoto | positive | Cryptosporidium spp. | positive |

| Petaurus breviceps | 4 month | 2.5 | Diarrhea | ND | negative | not investigated | – |

| Atelerix albiventris (four toed hedgehog) (Aa1) | 2 month | 2.5 | Hernia | Fukuoka | positive | Cryptosporidium spp. | positive |

| Atelerix albiventris (Aa2) | 2.5 month | 2 | Diarrhea | Kyoto | positive | not investigated | positive |

| Atelerix albiventris | 3 month | 2.5 | Diarrhea | ND | negative | not investigated | – |

| Atelerix albiventris | 2 month | 2.5 | Diarrhea | Fukuoka | negative | not investigated | – |

| Chinchilla lanigera (chinchilla) (Cl1) | 2 month | 2 | Loose stool | Oita | positive | not investigated | negative |

| Chinchilla lanigera (Cl2) | 3 month | 2 | Loose stool | Fukuoka | positive | not investigated | positive |

| Eublepharis macularius (leopard gecko) | 2 years | 2.5 | Severe diarrhea | Fukuoka | positive | not investigated | positive |

| Eublepharis macularius | 1 years | 3.5 | Anorexia, diarrhea | Fukuoka | negative | not investigated | – |

| Eublepharis macularius | ND | 3.5 | Anorexia, diarrhea | Fukuoka | negative | not investigated | – |

ND: No data, Body condition scores were assessed by veterinarians between 1 and 5. No clear criteria for body condition scores in these animals.

Fecal samples from sugar gliders and other animals were collected for a parasitological examination by sucrose centrifugal flotation and Kinyoun acid-fast staining, and also for DNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Cryptosporidium-specific fragments were amplified by a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting an ~830-bp fragment of the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene, as reported previously (Xiao et al., 2001). Regarding the subtyping of C. fayeri, the horse genotype, and C. ubiquitum, the Cryptosporidium 60-kDa glycoprotein gene (gp60) was amplified by nested PCR using primers, as reported previously (Sulaiman et al., 2005; Power et al., 2009; Li et al., 2014). PCR amplification was performed using KOD-Plus-Neo (TOYOBO, Japan), and positive fragments were purified using MonoFas DNA Purification Kit I (GL Science, Japan). DNA sequencing was conducted using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit on an automated ABI3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA). SSU rRNA and gp60 nucleotide sequences were sequenced using secondary primers. To detect other pathogens, fecal samples from the sugar glider and the four toed hedgehog were sent to the IDEXX company for PCR testing using the IDEXX Canine diarrhea RealPCR™ Panel (IDEXX Reference Laboratories, USA). This panel detects the following pathogens: Clostridium perfringens, Salmonella spp., Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., canine enteric coronavirus, canine parvovirus 2, and canine distemper virus.

The sequences of gp60 were aligned using Clustal X2 (Larkin et al., 2007). All gaps were eliminated. Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed using MEGA 7.0.26 (Kumar et al., 2016). Substitution models and optional parameter sets were also evaluated using MEGA 7.0.26, and the most suitable sets were selected according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). We constructed a phylogenetic tree, in which the substitution model and optional parameters used were the Tamura-Nei model (Tamura and Nei, 1993), incorporating the invariable site and Gamma distribution (five categories) options. To calculate the bootstrap value, 1000 ML trees were constructed using the same datasets. The protocol for the experiments was approved by the Committee on the Animal Experiments of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine.

3. Results

Table 1 shows information on the exotic animals surveyed in the present study. Of the 11 animals examined, 6 tested positive for Cryptosporidium on Kinyoun acid-fast staining. Only Cryptosporidium spp. were positive in the samples tested with the RealPCR™ Panel. A PCR analysis using SSU rRNA showed that all samples with Kinyoun acid-fast staining were positive for Cryptosporidium, except for one chinchilla (Cl1) sample. The SSU rRNA and gp60 genes were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers LC483882-LC483888 (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Information of exotic animals and Cryptosporidium detected in this study.

| Host | species | subtype | accession number |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU rRNA | GP60 | |||

| Petaurus breviceps | C. fayeri | IVaA13G2T1 | LC483882 | LC483886 |

| Atelerix albiventris (Aa1, Aa2) | Cryptosporidium horse genotype | VIbA13 | LC483885 | LC483888 |

| Chinchilla lanigera (Cl2) | C. ubiquitum | XIId | LC483883 | LC483887 |

| Eublepharis macularius | C. varanii | – | LC483884 | – |

The SSU rRNA and GP60 sequences detected form Aa1 and Aa2 were identical.

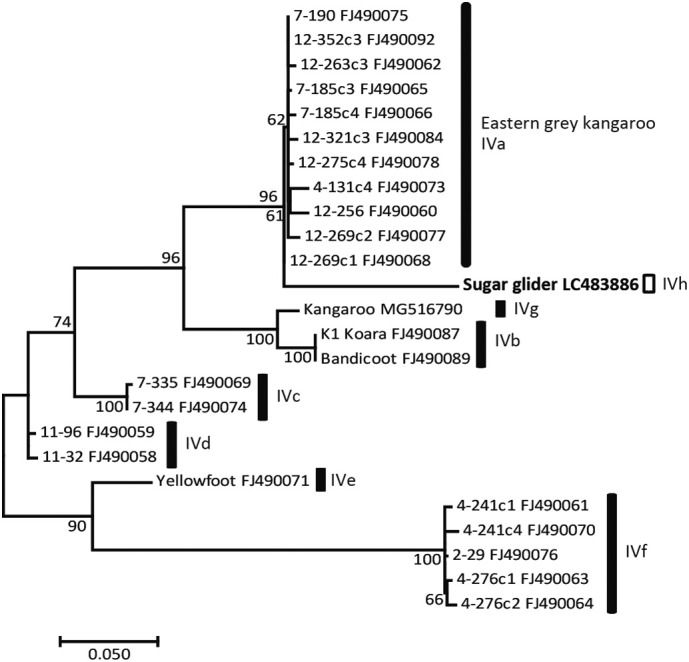

An NCBI blast (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search (blastn optimized for highly similar sequences) was used to search for the sequence with the highest homology to the detected sequence. The SSU rRNA gene sequences of Cryptosporidium from the sugar glider showed the highest homology with C. fayeri (AF112570) (100%, 758/758 bp homologous), and the gp60 sequence showed the highest homology with that of subtype family IVa in C. fayeri (FJ490092, isolate from a kangaroo). The gp60 sequence of C. fayeri had 90% homology (1036/1151 bp) with FJ490092, and Gap was present at 4% (47/1151 bp). Table 3 shows nucleotide sequence similarities (%) among the subtype families of C. fayeri (XIVa – IVh (detected in the present study)) at the gp60 gene. Fig. 1 shows the results of the phylogenetic analysis of the gp60 subtype of C. fayeri, including the sequence isolated from the sugar glider. Based on these results, the gp60 subtype family detected in this study, IVh, was proposed to be a new subtype family, and the gp60 serine-coding trinucleotide repeat of this isolate was IVhA13G2T1.

Table 3.

Nucleotide sequence similarity (%) among subtype families of C. fayeri (XIVa–IVh) at the gp60 locus.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on partial sequences of the gp60 gene in Cryptosporidium fayeri.

A phylogenetic tree based on partial sequences of the gp60 gene constructed by maximum likelihood (ML) analyses for C. fayeri using 911 nucleotides without gaps (substitution model and optional parameters = TN93 + Γ + I). Only bootstrap values >50% from 1000 pseudo-replicates are shown.

Cryptosporidium isolated from the hedgehog was 99% (780/784 bp) homologous in the SSU rRNA gene to the Cryptosporidium horse genotype (FJ435962) and the gp60 gene sequence was 100% (750/750 bp) homologous to FJ435961 (VIbA13). The SSU rRNA and gp60 sequences detected from Aa1 and Aa2 were identical (Table 2). Cryptosporidium isolated from the chinchilla was 100% (825/825 bp) homologous in the SSU rRNA gene to C. ubiquitum (KT922236) and the gp60 gene sequence was 100% (844/844 bp) homologous to that of LC334004 (XIId). Cryptosporidium isolated from the common leopard gecko was 99% (614/617 bp) homologous in the SSU rRNA gene to C. varanii (EU553556).

4. Discussion

The present study is the first to have detected C. fayeri from a sugar glider, a captive animal in Japan, and a novel C. fayeri subtype family (IVhA13G2T1) was identified. C. fayeri was previously identified as marsupial genotype I, with this pathogen being observed in Australian marsupials, such as the red kangaroo, koala, eastern grey kangaroo, yellow-footed rock wallaby, western-barred bandicoot, western grey kangaroo, and Tasmanian devils (Ryan and Power, 2012; Wait et al., 2017). These animals generally live on the ground, except for the koala. The gp60 sequence detected from the sugar glider in the present study formed a clade with the IVa subtype family isolated from eastern grey kangaroos in Australia (Power et al., 2009). The reported homology of the gp60 subtype family (IVa - IVg) is 76–95%. The sequence detected in the present study was 90% identical to the closest IVa, suggesting a new subtype family, IVh (Table 3).

Since the sugar glider in this survey was bred and sold at the same pet shop, we assumed that the pathogen was brought in with the infected animal (it may have originated from other sugar gliders) and spread among animals in the pet shop. In Japan, sugar gliders are mainly imported from the Republic of Indonesia and Thailand; however, there was no information on the origin of the sugar glider examined in the present study. The clinical symptoms of C. fayeri currently remain unclear. A previous study reported that adult eastern grey kangaroos shed oocysts, but remained asymptomatic (Power et al., 2005). In the present study, the 3-month-old sugar glider presented with diarrhea and weight loss. It tested positive for C. fayeri and negative for C. perfringens, Salmonella spp., and Giardia spp. The symptoms of diarrhea in this animal may have been caused by other pathogens, but suggest that C. fayeri causes digestive dysfunction symptoms in young sugar gliders. In a previous study, immunocompetent humans who had contact with marsupials were infected by C. fayeri (Waldron et al., 2010). In 2006, 8490 sugar gliders were imported into Japan (Ozone, 2006). In total, 8816 sugar gliders in 2014 and 7286 marsupials, including sugar gliders, in 2017 were imported into Japan (https://www.mhlw.go.jp/). The captive breeds of sugar gliders in Japan are a type of companion animal that make close contact with the owner. Furthermore, some tearooms in Japan allow humans to make contact with sugar gliders. Therefore, it is important to consider the risk of human infection with C. fayeri from sugar gliders and veterinarians need to adequately inform owners about this risk.

In the present study, the Cryptosporidium horse genotype was detected in a hedgehog. While C. parvum and C. erinacei (Cryptosporidium hedgehog genotypes) are common in hedgehogs (Kváč et al., 2014), only one previous study reported the detection of the Cryptosporidium horse genotype in an imported hedgehog in Japan (Abe and Matsubara, 2015). Isolates from the hedgehog were placed into the subtype VIb family (VIbA13), which is the same subtype reported in the present study. However, the clinical symptoms of the hedgehog in that study were not described. In the present study, the hedgehog had a hernia, and we found inflammation of the cranial intestine from the serosa during proctopexy. Hence, this pathogen may cause severe digestive symptoms in hedgehogs. While this species of pathogen is mainly detected in foals and calves (Thompson et al., 2007; Caffara et al., 2013), it has also been identified in immunocompetent humans (Robinson et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2009). Since the subtype of the horse genotype isolated from the hedgehog was similar to the genotype isolated from humans in a previous study (Xiao et al., 2009), infections in humans need to be considered. In total, 11,950 hedgehogs in 2014 and 14,479 in 2017 were imported into Japan (https://www.mhlw.go.jp/). Due to the large number of breeders in Japan, the prevention of infection and mitigation of potential epidemics are crucial.

C. ubiquitum was isolated from the chinchilla (Cl2). Cl1 was positive for cryptosporidium on acid-fast staining, but negative on PCR. The lack of amplification of SSU rDNA in Cl1 may have been due to the low intensity of oocysts in the fecal sample. This pathogen is isolated from many animals worldwide, such as ruminants, rodents, and primates, including humans (Fayer et al., 2010). In a previous study that examined 140 chinchillas in China, 1 chinchilla tested positive for C. parvum and 13 for C. ubiquitum, and the subtype was XIId (Qi et al., 2015). In the Czech Republic and Poland, C. ubiquitum was isolated from 2 out of 50 chinchillas, and the subtype was XIIa (Kellnerová et al., 2017). In an animal hospital in Japan, C. ubiquitum was isolated from 13 chinchillas, 11 of which had diarrhea and 8 of which died (Kubota et al., 2019). Similarly, the chinchilla in the present study had severe diarrhea. In Japan, C. ubiquitum has also been isolated from wild large Japanese field mice (Murakoshi et al., 2013); however, there is no information on the subtype. C. ubiquitum has recently been attracting increasing attention due to infections in humans, causing cryptosporidiosis (Fayer et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014). Since the chinchilla is a popular pet for humans, the zoonotic capability of C. ubiquitum needs to be considered.

C. varanii was isolated from the common leopard gecko. C. varanii is a common Cryptosporidium species isolated from numerous reptiles (Pavlasek and Ryan, 2008). In Japan, it has been isolated from a Baron's green racer, veiled chameleon, Chinese wonder geckos, and a common leopard gecko (Abe and Matsubara, 2015). This pathogen causes epidemics among reptiles. The main symptoms observed include anorexia, weight loss, and emaciation. Young reptiles are more prone to lethality with cryptosporidiosis (Deming et al., 2008; Dellarupe et al., 2016). In the present study, we found similar symptoms to those in previously reported cases of C. varanii infection.

These pathogens may have been introduced by infected animals imported from foreign countries or through infections contracted in pet shops or Japanese homes. Therefore, in order to prevent infection and epidemics in the future, investigations into the routes of infection of cryptosporidiosis are needed. Furthermore, the occurrence of these pathogens needs to be clarified by elucidating the rate of infection in captive animals in pet shops.

Ethical statement

Animal studies

The protocol for the experiments was approved by the Committee on the Animal Experiments of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (3805), and a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists of Kyoto Prefectural public university corporation.

References

- Abe N., Matsubara K. Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium isolates from exotic pet animals in Japan. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;209:254–257. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffara M., Piva S., Pallaver F., Iacono E., Galuppi R. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. from foals in Italy. Vet. J. 2013;198:531–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellarupe A., Unzaga J.M., Moré G., Kienast M., Larsen A., Stiebel C., Rambeaud M., Venturini M.C. Cryptosporidium varanii infection in leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) in Argentina. Open Vet. J. 2016;6:98–101. doi: 10.4314/ovj.v6i2.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deming C., Greiner E., Uhl E.W. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection and characteristics of oocyst shedding in a breeding colony of leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2008;39:600–607. doi: 10.1638/2006-016.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R. Taxonomy and species delimitation in Cryptosporidium. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;124:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R., Santín M., Macarisin D. Cryptosporidium ubiquitum n. sp. in animals and humans. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;172:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellnerová K., Holubová N., Jandová A., Vejčík A., McEvoy J., Sak B., Kváč M. First description of Cryptosporidium ubiquitum XIIa subtype family in farmed fur animals. Eur. J. Protistol. 2017;59:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota R., Matsubara K., Tamukai K., Ike K., Tokiwa T. Molecular and histopathological features of Cryptosporidium ubiquitum infection in imported chinchillas Chinchilla lanigera in Japan. Parasitol. Int. 2019;68:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M., Hofmannová L., Hlásková L., Květoňová D., Vítovec J., McEvoy J., Sak B. Cryptosporidium erinacei n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in hedgehogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;201:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N.P., Chenna R., McGettigan P.A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I.M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Higgins D.G. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Xiao L., Alderisio K., Elwin K., Cebelinski E., Chalmers R., Santin M., Fayer R., Kvac M., Ryan U., Sak B., Stanko M., Guo Y., Wang L., Zhang L., Cai J., Roellig D., Feng Y. Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:217–224. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.121797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakoshi F., Fukuda Y., Matsubara R., Kato Y., Sato R., Sasaki T., Tada C., Nakai Y. Detection and genotyping of Cryptosporidium spp. in large Japanese field mice, Apodemus speciosus. Vet. Parasitol. 2013;196:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozone M. Notification system for the importation of animals and current state of importation. Modern Media. 2006;52:343–351. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Pavlasek I., Ryan U. Cryptosporidium varanii takes precedence over C. saurophilum. Exp. Parasitol. 2008;118:434–437. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power M.L., Sangster N.C., Slade M.B., Veal D.A. Patterns of Cryptosporidium oocyst shedding by eastern grey kangaroos inhabiting an Australian watershed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:6159–6164. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6159-6164.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power M.L., Cheung-Kwok-Sang C., Slade M., Williamson S. Cryptosporidium fayeri: diversity within the GP60 locus of isolates from different marsupial hosts. Exp. Parasitol. 2009;212:219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M., Luo N., Wang H., Yu F., Wang R., Huang J., Zhang L. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in pet chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera) in China. Parasitol. Int. 2015;64:339–341. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson G., Elwin K., Chalmers R.M. Unusual Cryptosporidium genotypes in human cases of diarrhea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:1800–1802. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.080239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan U., Power M. Cryptosporidium species in Australian wildlife and domestic animals. Parasitology. 2012;139:1673–1688. doi: 10.1017/S0031182012001151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan U.M., Power M., Xiao L. Cryptosporidium fayeri n sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) from the red kangaroo (Macropus rufus) J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2008;55:22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2007.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman I.M., Hira P.R., Zhou L., Al-Ali F.M., Al-Shelahi F.A., Shweiki H.M., Iqbal J., Khalid N., Xiao L. Unique endemicity of cryptosporidiosis in children in Kuwait. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:2805–2809. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2805-2809.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H.P., Dooley J.S.G., Kenny J., McCoy M., Lowery C.J., Moore J.E., Xiao L. Genotypes and subtypes of Cryptosporidium spp. in neonatal calves in Northern Ireland. J. Parasitol. Res. 2007;100:619–624. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wait L.F., Fox S., Peck S., Power M.L. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron L.S., Cheung-Kwok-Sang C., Power M.L. Wildlife-associated Cryptosporidium fayeri in human. Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:2006–2007. doi: 10.3201/eid1612.100715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Bern C., Limor J., Sulaiman I., Roberts J., Checkley W., Cabrera L., Gilman R.H., Lal A.A. Identification of 5 types of Cryptosporidium parasites in children in Lima. Peru. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;183:492–497. doi: 10.1086/318090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Hlavsa M.C., Yoder J., Ewers C., Dearen T., Yang W., Nett R., Harris S., Brend S.M., Harris M., Onischuk L., Valderrama A.L., Cosgrove S., Xavier K., Hall N., Romero S., Young S., Johnston S.P., Arrowood M., Roy S., Beach M.J. Subtype analysis of Cryptosporidium specimens from sporadic cases in Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, and Iowain 2007: widespread occurrence of one Cryptosporidium hominis subtype and case history of an infection with the Cryptosporidium horse genotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:3017–3020. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00226-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]