This cross-sectional study assesses the use of general and specialized primary care, medical specialty, and mental health services among patients aat high risk of hospitalization in the Veterans Health Administration.

Key Points

Question

Within the Veterans Health Administration, what is the role of general primary care, specialized primary care, mental health, and medical specialty services in caring for veterans at high risk for hospitalization?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study, veterans at high risk for hospitalization had significantly more mental health encounters than primary care encounters and significantly more primary care encounters than medical specialty encounters. Most high-risk veterans (88%) were cared for in general primary care rather than in specialized primary care.

Meaning

The findings suggest that health care system leaders should recognize the critical roles of general primary care and mental health for high-risk patients.

Abstract

Importance

Integrated health care systems increasingly focus on improving outcomes among patients at high risk for hospitalization. Examining patterns of where patients obtain care could give health care systems insight into how to develop approaches for high-risk patient care; however, such information is rarely described.

Objective

To assess use of general and specialized primary care, medical specialty, and mental health services among patients at high risk of hospitalization in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This national, population-based, retrospective cross-sectional study included all veterans enrolled in any type of VHA primary care service as of September 30, 2015. Data analysis was performed from April 1, 2016, to January 1, 2019.

Exposures

Risk of hospitalization and assignment to general vs specialized primary care.

Main Outcome and Measures

High-risk veterans were defined as those who had the 5% highest risk of near-term hospitalization based on a validated risk prediction model; all others were considered low risk. Health care service use was measured by the number of encounters in general primary care, specialized primary care, medical specialty, mental health, emergency department, and add-on intensive management services (eg, telehealth and palliative care).

Results

The study assessed 4 309 192 veterans (mean [SD] age, 62.6 [16.0] years; 93% male). Male veterans (93%; odds ratio [OR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.10-1.13), unmarried veterans (63%; OR, 2.30; 95% CI, 2.32-2.35), those older than 45 years (94%; 45-65 years of age: OR, 3.49 [95% CI, 3.44-3.54]; 66-75 years of age: OR, 3.04 [95% CI, 3.00-3.09]; and >75 years of age: OR, 2.42 [95% CI, 2.38-2.46]), black veterans (23%; OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.61-1.64), and those with medical comorbidities (asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 33%; OR, 4.03 [95% CI, 4.00-4.06]; schizophrenia: 4%; OR, 5.14 [95% CI, 5.05-5.22]; depression: 42%; OR, 3.10 [95% CI, 3.08-3.13]; and alcohol abuse: 20%; OR, 4.54 [95% CI, 4.50-4.59]) were more likely to be high risk (n = 351 012). Most (308 433 [88%]) high-risk veterans were assigned to general primary care; the remaining 12% (42 579 of 363 561) were assigned to specialized primary care (eg, women’s health and homelessness). High-risk patients assigned to general primary care had more frequent primary care visits (mean [SD], 6.9 [6.5] per year) than those assigned to specialized primary care (mean [SD], 6.3 [7.3] per year; P < .001). They also had more medical specialty care visits (mean [SD], 4.4 [5.9] vs 3.7 [5.4] per year; P < .001) and fewer mental health visits (mean [SD], 9.0 [21.6] vs 11.3 [23.9] per year; P < .001). Use of intensive supplementary outpatient services was low overall.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that, in integrated health care systems, approaches to support high-risk patient care should be embedded within general primary care and mental health care if they are to improve outcomes for high-risk patient populations.

Introduction

Patients at high risk for hospitalization are heterogeneous1 and complex to treat,2,3 and they typically have multiple chronic medical conditions, often compounded by mental health conditions.4,5,6 A frequent assumption has been that many of these high-risk patients receive mostly acute emergency care.7 Another common assumption has been that high-risk patients with complex conditions receive care mostly through medical specialists,8,9 whereas primary care is predominantly directed at a lower-risk population. High-risk patients are often assumed to have low levels of health literacy and to be uninterested in electronic communication with their health care practitioners.10 We aimed to inform health care system level planning for high-risk patient care by testing assumptions about whether, where, and how the more than 350 000 highest-risk patients cared for nationally in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) receive outpatient care.

Primary care settings in integrated health care systems aim to provide care that is coordinated, comprehensive, continuous, and assessible.11 Specialty or subspecialty settings, on the other hand, predominantly aim to provide accessible, short-term consultative care. Even when specialists provide long-term continuity care, as they often do for some patients,8,12,13,14 they typically do not aim to provide full primary care, defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs.”15(p1)16 Sometimes, however, specialists or specialized teams serve as alternatives to general primary care. These specialized primary care settings aim to provide comprehensive, continuous primary care to a population with special needs, such as those with HIV infection,17 homeless veterans,18 or those with serious mental illnesses.19

In this study, we sought to characterize patterns of care for the top 5% of the highest-risk patients enrolled in the VHA nationally based on a predictive risk score for near-term hospitalization that is generated for all VHA patients. We expected that high-risk patients, compared with low-risk patients, would use more face-to-face and fewer secure message encounters with primary care. We also expected that half of high-risk patients would be cared for in specialized primary care settings and that more than half of specialized primary care patients would be high risk. We hypothesized that high-risk patients assigned to general primary care, compared with those assigned to specialized primary care, would have both more primary care and more medical specialty care visits. We aimed to compare (1) primary care encounters (face-to-face, telephone, and secure messages) among high-risk vs low-risk patients, (2) the proportions of high-risk patients assigned to general vs specialized primary care, and (3) the use of primary care and medical (nonsurgical) specialty care visits among high-risk patients assigned to general vs specialized primary care.

Methods

Patients

For this cross-sectional study, we used national electronic administrative data from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse for veterans enrolled in the VHA in 2015. The study population included all VHA patients assigned to primary care (general or specialized) as of September 30, 2015 (n = 4 309 192). This evaluation was designed to support VHA operations under the authority of VHA National Office of Primary Care.20 Patient consent was waived with permission of the VHA National Office of Primary Care because this study was designed for internal VA purposes in support of the VA mission. The findings were designed to be used by and within VA for program and planning purposes. Data were deidentified. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Setting

Since national implementation of the patient-centered medical home model in more than 900 locations in the VHA in 2010,21,22 nearly all patients have been assigned at enrollment to a continuity primary care practitioner (physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) who works with a care team that includes a registered nurse care manager, licensed practical nurse, and clerk.19,21,23,24,25,26,27 Patients are assigned to a general or specialized primary care team and may switch to another general or specialized primary care team at any time after enrollment. All teams are tasked with providing comprehensive primary care, including screening and preventive care services.27,28 Most general primary care sites are community based, whereas most specialized primary care sites other than those for women’s health are medical center based.29

As an integrated health care system, the VHA provides a full range of specialty services, including consultative medical and surgical specialty care as well as integrated primary care and mental health care.30 In addition, the VHA offers supplementary services for intensifying care, such as telehealth (remote monitoring for chronic medical conditions),31 palliative care, and housing services. The VHA offers multiple modalities to access primary care, including telephone and secure messaging.

Measures

Exposures

We assessed assignment to the type of primary care setting on September 30, 2015, based on administrative data. We assessed for assignment to general primary care and 7 diverse but commonly available types of specialized primary care that together accounted for 98% of patients enrolled in any type of VHA primary care.32 We focused on geriatric, homelessness, and women’s health settings as cognitive, nonprocedural services; HIV and dialysis as technical, specialized services; and home-based care and spinal cord injury as disability-focused services.

Risk Level

The VHA calculates Care Assessment Needs (CAN) scores28,33 weekly for all enrolled veterans who are assigned to any (general or specialized) primary care practitioner and are not hospitalized at the time of CAN score generation. We used an updated CAN model33 (eTable 1 in the Supplement) to assess hospitalization risk using VHA administrative data on demographics, use of VHA health services, comorbidity indicators, prescribed medications, vital signs, and veteran-specific variables. The top 5% of patients identified by CAN score have an almost 20% risk of VHA hospitalization within the following 90 days.28

We defined the high-risk patient cohort as all patients with a CAN score in the 95th or greater percentile at any time during April 1, 2015, through September 30, 2015 (n = 351 012). We excluded patients who had died during this period for the purpose of assigning a CAN score. We defined the remainder of patients (n = 3 958 180) as low risk. We used the first date that a patient qualified as high risk and the last date (ie, September 30, 2015) for low-risk patients as the index dates for our analyses.

Patient Characteristics

We assessed sample patient demographics based on administrative data and medical and psychiatric comorbidities using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (eTable 2 in the Supplement) during the year before the patient’s index date. Housing stability was defined by a combination of ICD-9 code or receipt of housing services in outpatient encounter data.34 We assessed potentially qualifying characteristics for 4 types of specialized primary care (geriatrics, homelessness, women’s health, and HIV) based on age (>70 years of age), housing instability (defined above), sex (female), and HIV status (defined by ICD-9 code).

Use of VHA Services

We counted all patient encounters coded during 2 periods: 1 year before each patient’s index date for high-risk identification (in 2015) and 1 year after the VHA fiscal year 2016 (October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2016). We used the VA Support Service Center35 data definitions for primary care encounter types (in-person or telephone) as recorded in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse.36 We used the My HealtheVet patient portal database for data related to secure messages. We counted only 1 encounter per encounter type for any single day. We also counted all nonsurgical specialty encounters (including mental health), inpatient admissions, and emergency department encounters. We performed a sensitivity analysis on use among patients who were alive throughout the VHA fiscal year 2016 (99.4% of the high-risk cohort) and found minor changes (eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Outpatient Encounters

We categorized outpatient encounters into the following 5 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive groups using established data definitions during VHA fiscal year 201637: any in-person primary care (general or specialized), any in-person mental health (primary care and mental health integration,30 individual and group psychotherapy, or substance use), any in-person medical specialty (excluding encounters related to procedures and chemotherapy), emergency department, or all other (eg, any telephone, surgical, physical therapy, occupational therapy, dental, nutrition, anticoagulation clinic, procedures, chemotherapy, telehealth, and radiology).

Add-on Services

We defined add-on services as those designed to supplement primary care for added care intensity. We assessed use of 4 add-on services during VHA fiscal year 2016 with particular relevance to high-risk patients: palliative care, telehealth disease management for chronic conditions, intensive mental health case management (similar to assertive community treatment),38 and housing services.

Statistical Analysis

We used unadjusted logistic regression to generate odds ratios (ORs) for being a high-risk patient (defined by the CAN score) based on veteran characteristics (eg, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and medical condition). We used 2-sample t tests to assess differences between veterans at high risk for hospitalization vs those at low risk for hospitalization in rates of primary care visits, emergency department visits, and in-patient discharges. We tested mean use differences between patients assigned to general vs specialized primary care using 2-sample t tests and 1-way analysis of variance using the Tukey multiple comparison test.39 For all statistical tests, we used a 2-sided P < .05 as the a priori significance level and performed 2-tailed hypothesis tests. We performed successive analyses from April 1, 2016, to January 1, 2019. Analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

The study assessed 4 309 192 veterans (mean [SD] age, 62.6 [16] years; 93% male). Male veterans (93%; odds ratio [OR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.10-1.13), unmarried veterans (63%; OR, 2.30; 95% CI, 2.32-2.35), those older than 45 years (94%; 45-65 years of age: OR, 3.49 [95% CI, 3.44-3.54]; 66-75 years of age: OR, 3.04 [95% CI, 3.00-3.09]; and >75 years of age: OR, 2.42 [95% CI, 2.38-2.46]), black veterans (23%; OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.61-1.64), and those with medical comorbidities (asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 33%; OR, 4.03 [95% CI, 4.00-4.06]; schizophrenia: 4%; OR, 5.14 [95% CI, 5.05-5.22]; depression: 42%; OR, 3.10 [95% CI, 3.08-3.13]; and alcohol abuse: 20%; OR, 4.54 [95% CI, 4.50-4.59]) were more likely to be high risk (n = 351 012) (Table 1).Compared with low-risk patients (n = 3 958 180), high-risk patients (n = 351 012) had 2.5 times the face-to-face, 4 times the telephone, and twice the number of secure messaging encounters in primary care during the year before being identified as being high risk for hospitalization. Based on the CAN score, which includes rates of acute care use,33 high-risk patients had substantially more mean hospital visits (0.8 [1.1] vs 0.02 [0.2], P < .001) and emergency department visits (2.1 [2.6] vs 0.2 [0.7], P < .001) per year than low-risk patients during the same period.

Table 1. Characteristics and Health Service Use of High-Risk and Low-Risk Veteransa.

| Variable | High-risk veterans (n = 351 012) | Low-risk veterans (n = 3 958 180) | Odds ratio (95% CI) or P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 327 443 (93.3) | 3 665 273 (92.6) | 1.11 (1.10-1.13) |

| Not married | 218 418 (62.8) | 1 639 231 (42.0) | 2.33 (2.32-2.35) |

| Service connection ≥50%c | 146 181 (72.7) | 1 151 896 (55.2) | 2.17 (2.14-2.19) |

| Housing instability | 28 805 (8.2) | 59 562 (1.5) | 5.85 (5.77-5.94) |

| Age, y | |||

| <45 | 20 452 (5.8) | 631 976 (16.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| 45-65 | 151 613 (43.2) | 1 343 279 (33.9) | 3.49 (3.44-3.54) |

| 66-75 | 116 027 (33.1) | 1 178 532 (29.8) | 3.04 (3.00-3.09) |

| >75 | 62 920 (17.9) | 804 393 (20.3) | 2.42 (2.38-2.46) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 195 584 (66.2) | 2 203 010 (73.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 69 554 (23.5) | 481 256 (16.1) | 1.63 (1.61-1.64) |

| Hispanic | 18 963 (6.4) | 188 781 (6.3) | 1.13 (1.11-1.15) |

| Medical comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 259 361 (73.9) | 2 055 111 (52.5) | 2.56 (2.54-2.58) |

| Diabetes | 155 226 (44.2) | 913 274 (23.1) | 2.65 (2.63-2.66) |

| Asthma or COPDd | 117 234 (33.4) | 425 815 (11.1) | 4.03 (4.00-4.06) |

| Congestive heart failure | 82 037 (23.4) | 117 827 (3.0) | 9.94 (9.85-10.04) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14 229 (4.1) | 22 615 (0.6) | 7.35 (7.20-7.51) |

| Arthritis | 178 655 (50.9) | 1 300 670 (33.2) | 2.08 (2.07-2.10) |

| Schizophreniad | 19 261 (5.5) | 43 039 (1.1) | 5.14 (5.05-5.22) |

| Depressiond | 145 738 (41.5) | 729 080 (18.6) | 3.10 (3.08-3.13) |

| Alcohol abused | 69 774 (19.9) | 202 734 (5.2) | 4.54 (4.50-4.59) |

| Dementia | 35 794 (10.2) | 101 343 (2.6) | 4.32 (4.27-4.38) |

| Health service use during the past year, mean (SD) | |||

| Any face-to-face primary care encountersd | 6.3 (6.6) | 2.5 (2.9) | <.001 |

| Any primary care telephone encountersd | 4.0 (4.9) | 1.0 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Any primary care secure messages | 2.7 (12.7) | 1.2 (6.5) | <.001 |

| Hospitalizationsd | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.02 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Emergency department visitsd | 2.1 (2.6) | 0.2 (0.7) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Characteristics or health service use during the year before identification as high or low risk (index date).

Odds ratios are the odds of being high risk among those having the characteristic compared with the odds of being high risk among those not having the characteristic. The odds ratio can overestimate the relative risk when the outcome of interest occurs in greater than 10% of the sample.

Service-connected disability refers to a monetary benefit paid to veterans who are determined by the Veterans Health Administration to be disabled by an injury or illness that was incurred or aggravated during active military service.

An element of the Veterans Health Administration risk score for hospitalization (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

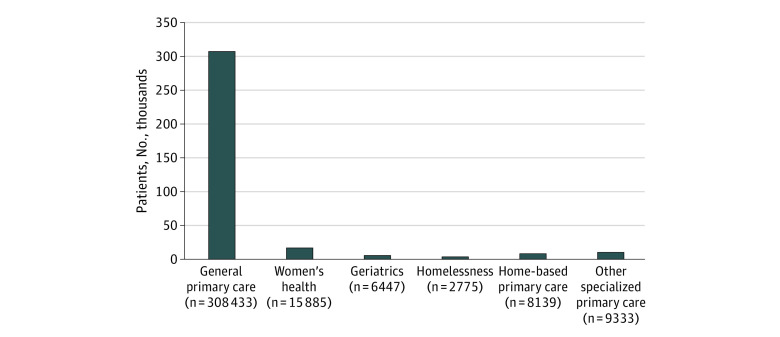

Figure 1 shows that most high-risk patients (308 433 of 351 012 [88%]) were assigned to general care than to specialized primary care. Of the remaining high-risk patients, 5% were assigned to women’s health, 2% to geriatrics, 2% to home-based primary care, 0.8% to homelessness primary care, 0.8% to HIV care, 0.8% to spinal cord injury care, 0.2% to dialysis, and 0.9% to all other specialized primary care settings.

Figure 1. Distribution of Where 351 012 High-Risk Veterans Received Primary Care as of September 30, 2015.

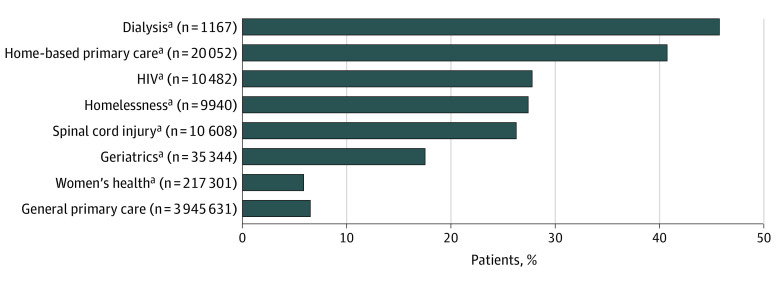

As shown in Figure 2, among all patients (both high- and low-risk patients) assigned to general primary care, 8% (308 433 of 3 945 631) were high risk. Among all patients assigned to any specialized primary care setting, 12% (42 579 of 363 561) were high risk. The proportions of high-risk patients varied across the 7 specialized primary care settings, ranging from 46% (532 of 1167) of dialysis primary care to 7% (15 885 of 217 301) of women’s health primary care.

Figure 2. Proportions of 4 309 192 High-Risk Patients in Veterans Health Administration General Primary Care and 7 Specialized Primary Care Settings .

Data as of September 30, 2015.

aP < .05 when comparing general primary care with each specialized primary care setting using Tukey-style multiple comparisons of proportions.

We found varying patterns of primary care assignment when we assessed assignment with respect to potentially qualifying characteristics (age >70 years, homelessness, HIV, and women’s health). Among the 3 more cognitive specialized primary care services, 6% (5821 of 98 181) of high-risk patients older than 70 years were assigned to geriatrics primary care compared with 85% (83 846 of 98 181) in general primary care, with the remaining 9% in other specialized primary care settings. Among high-risk homeless patients, 5% (2468 of 52 506) were assigned to homelessness primary care compared with 85% (44 600 of 52 506) in general primary care, with the remaining 10% in other specialized primary care settings. For high-risk women, 68% (16 020 of 23 569) were assigned to women’s health compared with 28% (6598 of 23 569) assigned to general primary care. For specialized HIV primary care, a highly technical primary care service, 51% (2836 of 5581) of patients diagnosed with HIV infection were assigned to specialized HIV primary care compared with 45% (2533 of 5581) assigned to general primary care.

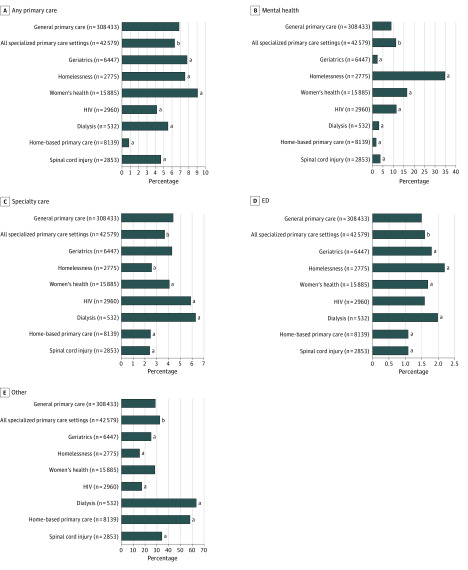

As shown in Figure 3, general and specialized primary care patients had substantial use of primary care, mental health, and emergency department services during the year after they were identified as high risk (eTable 3 in the Supplement). However, high-risk specialized primary care patients had significantly more outpatient visits (mean [SD], 55.6 [40.3] per year) than did those enrolled in general primary care (mean [SD], 50.5 [35.8] per year; P < .001). Compared with specialized primary care patients, general primary care patients had significantly more face-to-face primary care encounters (mean [SD], 6.9 [6.5] per year general vs 6.3 [7.3] per year specialized primary care; P < .001) and medical specialty encounters (mean [SD], 4.4 [5.9] per year general vs 3.7 [5.4] per year specialized primary care; P < .001). High-risk patients assigned to general primary care had significantly fewer mental health (9.0 [21.6] per year general vs 11.3 [23.9] per year specialized primary care; P < .001), emergency department (mean [SD], 1.5 [2.5] per year general vs 1.6 [2.7] per year specialized primary care; P < .001), and other (eg, telephone, surgical, telehealth, and physical therapy) (mean [SD], 28.9 [24.5] per year general vs 32.8 [30.8] per year specialized primary care; P < .001) encounters. Two types of specialized primary care had substantially higher rates of mental health use than other primary care settings (mean [SD], 16.4 [26.4] per year for women’s health and 34.6 [39.1] per year for homelessness).

Figure 3. Mean Number of Veterans Health Administration Ambulatory Encounters During 1 Year Among High-Risk Patients by Primary Care Setting.

Mean counts of any in-person primary care (general or specialized), any mental health, any medical specialty, or any emergency department (ED) face-to-face visit from October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2016. Other encounters include any outpatient telephone, telehealth, surgical, radiology, rehabilitation, and procedural visits. Quantitative results are also given in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Two-sample t tests were used for each encounter type comparing patients enrolled in general vs specialized primary care. We performed the Tukey multiple comparison procedure to assess differences in means.

aP < .05.

bP < .001.

Overall, few high-risk patients used add-on services for intensifying primary care (Table 2). Among the 351 012 high-risk patients in our study, 10.9% (38 354) received telehealth monitoring for chronic conditions (eg, hypertension and diabetes), 6.8% (23 827) received housing services, 4.1% (14 545) received palliative care or hospice, and 1.6% (5620) received intensive mental health case management. Different specialized primary care settings, however, used these add-on services at different rates. For example, 4.5% (124 of 2775) of homeless primary care high-risk patients received telehealth services, whereas 53.5% (1484 of 2775) received housing services. In contrast, 15.9% (1291 of 8139) of home-based primary care high-risk patients received telehealth services, whereas 0.7% (70 of 8139) received housing services.

Table 2. Receipt of Any Add-on Intensive Services by Primary Care Type From October 1, 2015, Through September 30, 2016.

| Add-on intensive service | No. (%) of veterans | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General primary care (n = 308 433) | Specialized primary care | Total (N = 351 012) | |||||

| Women’s health (n = 15 885) | Geriatrics (n = 6447) | Homelessness (n = 2775) | Home based (n = 8139) | Other (n = 9333)a | |||

| Telehealth services | 33 898 (11.0) | 1578 10.0) | 746 (11.6) | 124 (4.5) | 1291 (15.9) | 717 (7.7) | 38 354 (10.9) |

| Palliative care or hospice services | 12 392 (4.0) | 302 (1.9) | 629 (9.8) | 47 (1.7) | 859 (10.6) | 316 (3.4) | 14 545 (4.1) |

| Intensive mental health case management services | 4849 (1.6) | 487 (3.1) | 33 (0.5) | 79 (2.8) | 71 (0.9) | 101 (1.1) | 5620 (1.6) |

| Housing services | 19 927 (6.5) | 1525 (9.6) | 65 (1.0) | 1484 (53.5) | 70 (0.9) | 756 (8.1) | 23 827 (6.8) |

Other refers to specialized primary care for patients with HIV, end-stage renal disease while receiving dialysis, and spinal cord injury.

Discussion

High-risk patients in the VHA are a small fraction of the general population but account for nearly half of overall health care costs,40 most of which are accounted for by hospitalizations.5 Contrary to expectations, we found that most high-risk veterans (88%) were assigned to general primary care rather than specialized primary care. Patients assigned to general primary care had more mental health and primary care visits than medical specialty visits. High-risk patients used all types of encounters, including in-person, telephone, and secure messaging, at higher rates than low-risk patients.

Our findings challenge health care systems and researchers to consider the roles, goals, and implications of general primary care for high-risk patient populations. Health care systems are already providing risk-stratified care management, as in the Medicare Comprehensive Primary Care Plus Initiative,41,42,43 and turning to specialized programs or intensive primary care models26 to manage high-risk patient populations. Although specialized programs or intensive primary care models potentially offer important benefits to high-risk patients, these settings are often more resource intensive than general primary care26,27,44,45,46,47,48 and more available in urban areas.49

One reason for investing in specialized primary care teams is to provide expertise and resources to special populations that may be more complex than the general primary care population. Overall, we found that most patients assigned to specialized settings were low risk. We also found that even among patients with a technically demanding condition, such as HIV infection, only half of patients with the condition were followed up in specialized primary care. The single exception was for high-risk women veterans, among whom two-thirds were enrolled in specialized women’s health teams. This finding is likely attributable to the need for sex-specific specialized services and procedures50,51 and the VHA’s effort to provide specialized support to designated women’s health primary care practitioners at a distance to meet this need, such as through Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes.52 Further investigation is warranted.

Our findings suggest that developing population-based approaches for supporting needed high-risk patient care modalities within general primary care settings may be more beneficial than carve-out specialized or intensive primary care programs. Multiple investigations9,26,41,53,54,55,56,57 in VHA and non-VHA settings indicate that intensive case management for high-risk patients rarely achieves expected cost savings, whereas access to comprehensive primary care has been associated with improved outcomes, decreased mortality, lower hospitalization rates, emergency department visits, and health care costs both outside58,59,60,61,62,63 and inside22,37,64,65 the VHA. However, key care modalities known to be needed by high-risk patients are not easily accessible to general primary care teams. For example, time constraints in primary care and training needs can make it challenging to perform assessments for known risk factors, such as falls, cognitive impairment, social isolation, medication adherence, or mental health issues. These assessments may be a starting point for more effective use of specialists and other relevant health care resources for chronic disease management and for care coordination.32,44,66,67 In addition, training and support from specialists at a distance68,69 or expansion of add-on services could potentially improve general primary care effectiveness for high-risk patients, building on efforts currently under way in the VHA.70,71

Our findings also highlight the burden of mental health conditions and high rates of mental health service use among veterans who are at high risk for hospitalization. Further investigations into the patterns of mental health care among high-risk patients may be helpful for developing a focus on the complex needs of these patients within the primary care and mental health integration program.30

Limitations

This study has limitations. It is descriptive and does not address causation. Our VHA-based findings may not be generalizable to other health care systems or to fee-for-service health care settings that may incentivize specialty care.72 Our findings have implications, however, for any large system that aims to provide equitable access to care across an enrolled population. Furthermore, although VHA enrollees have higher rates of psychosocial conditions than non-VHA populations,72,73 higher psychosocial condition rates are typical for high-risk patients in most health care systems. Additional limitations are that we did not assess non-VA use of care74; we studied only how many encounters of particular types occurred without potentially relevant modeling information, such as patient functional status or distance to specialized care settings. Similarly, our data did not support analyses based on specialized primary care enrollment criteria; we used only very general indicators. In addition, our encounter data do not include slight recent VHA coding changes that resulted in a very small proportion of telephone visits being counted as in-person visits; distributions of in-person visits, however, were similar using alternative VHA data definitions.

Conclusions

Achieving the triple aim of improving patient experience of care, improving population health, and reducing per capita health care costs among high-risk patients75 has proved to be elusive.9,26,41,53,54,55,56 Our data suggest that a better understanding of existing and optimal roles of different types of primary and specialty care for high-risk patient populations may be critical for achieving the triple aim. Planning for high-risk patient care improvement in integrated health care systems such as the VHA should focus on enabling high-quality complex patient care within primary care and mental health services. In this study, many high-risk veterans were avid users of electronic and telephone care, suggesting that opportunities exist to improve care through maximizing the accessibility and effectiveness of non–face-to-face modalities. Overall, our findings provide a foundation for investigation aimed at informing better design of health care programs and resources that can engage patients in their existing locations of care.

eTable 1. Care Assessment Needs (CAN) 2.0 Model Coefficients, Odds Ratios, and Associated 95% Confidence Intervals for Hospitalization 90-Day Model

eTable 2. ICD-9 Codes for Selected Medical and Behavioral Conditions

eTable 3. Average Number of VHA Ambulatory Encounters Over One Year Among High-Risk Patients, by Primary Care Settinga (October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016)

eTable 4. Average Number of VHA Ambulatory Encounters Over One Year Among High-Risk Patients Alive Throughout VHA Fiscal Year 2016, by Primary Care Settinga (October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016)

eTable 5. Receipt of Any Add-On Intensive Services by Primary Care Type Among High-Risk Patients Alive Throughout VHA Fiscal Year 2016 (October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016)

References

- 1.Long P, Abrams M, Milstein A, et al. . Effective Care for High-Need Patients: Opportunities for Improving Outcomes, Values, and Health. National Academy of Medicine; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frandsen BR, Joynt KE, Rebitzer JB, Jha AK. Care fragmentation, quality, and costs among chronically ill patients. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(5):355-362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming MD, Shim JK, Yen IH, et al. . Patient engagement at the margins: health care providers’ assessments of engagement and the structural determinants of health in the safety-net. Soc Sci Med. 2017;183:11-18. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, et al. . Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Wagner TH, et al. . Multimorbidity and healthcare utilisation among high-cost patients in the US Veterans Affairs Health Care System. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007771. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter G, Yoon J, Blonigen DM, Asch SM, Zulman DM. Health care utilization patterns among high-cost VA patients with mental health conditions. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(9):952-958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huget JL. Super-utilizers place huge burden on health-care system. Washington Post October 22, 2012. Accessed May 22, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-checkup/post/super-utilizers-place-huge-burden-on-health-care-system/2012/10/19/c62781ba-1a32-11e2-ad4a-e5a958b60a1e_blog.html

- 8.Mendenhall RC, Moynihan CJ, Radecki SE. The relative complexity of primary care provided by medical specialists. Med Care. 1984;22(11):987-1001. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198411000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon J, Chang E, Rubenstein LV, et al. . Impact of primary care intensive management on high-risk veterans’ costs and utilization: a randomized quality improvement trial. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(12):846-854. doi: 10.7326/M17-3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin R. Secure messaging: myths, facts, and pitfalls. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(1):21-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Defining Primary Care An Interim Report. Part 2, Earlier Definitions of Primary Care: A Review. National Academies Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forrest CB. A typology of specialists’ clinical roles. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1062-1068. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiken LH, Lewis CE, Craig J, Mendenhall RC, Blendon RJ, Rogers DE. The contribution of specialists to the delivery of primary care. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(24):1363-1370. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM, Chan L, Schneeweiss R. The generalist role of specialty physicians: is there a hidden system of primary care? JAMA. 1998;279(17):1364-1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, eds. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. National Academies Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donaldson M, Yordy K, Vanselow N, eds. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Defining Primary Care: An Interim Report. National Academies Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beane SN, Culyba RJ, DeMayo M, Armstrong W. Exploring the medical home in Ryan White HIV care settings: a pilot study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(3):191-202. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Aiello R, Kane V, Pape L. Tailoring care to vulnerable populations by incorporating social determinants of health: the Veterans Health Administration’s “Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team” program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E44. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.150567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alakeson V, Frank RG, Katz RE. Specialty care medical homes for people with severe, persistent mental disorders. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):867-873. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veterans Health Administration Program Guide: 1200.21: VHA operations activities that may constitute research In: VHA Handbook. US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2019:13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. . The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. . Implementation of the patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration: associations with patient satisfaction, quality of care, staff burnout, and hospital and emergency department use. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1350-1358. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson K, Sun H, Dolan E, et al. . Elements of the patient-centered medical home associated with health outcomes among veterans: the role of primary care continuity, expanded access, and care coordination. J Ambul Care Manage. 2014;37(4):331-338. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing Patient-Centered Medical Homes in the Nation’s Largest Integrated Delivery System. Commonwealth Fund; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yano EM, Bair MJ, Carrasquillo O, Krein SL, Rubenstein LV. Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT): VA’s journey to implement patient-centered medical homes. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(suppl 2):S547-S549. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2835-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards ST, Peterson K, Chan B, Anderson J, Helfand M. Effectiveness of intensive primary care interventions: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1377-1386. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4174-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter ME, Pabo EA, Lee TH. Redesigning primary care: a strategic vision to improve value by organizing around patients’ needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(3):516-525. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, et al. . Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2013;51(4):368-373. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827da95a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Veterans Affairs , Veterans Health Administration. Veterans Health Administration Clinical Inventory. Accessed March 16, 2018. http://vaww.vssc.med.va.gov/ClinicalInventory/FacilitySearch/FacilitySearch.aspx

- 30.Pomerantz AS, Sayers SL. Primary care-mental health integration in healthcare in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):78-82. doi: 10.1037/a0020341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldonado A, Rodriguez L, Renfro D, Sheridan SB, McElrath M, Chardos J. A home telehealth heart failure management program for veterans through care transitions. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2013;32(4):162-165. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0b013e318299f834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veterans Health Administration Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) Handbook: VHA Handbook 1101.10(1). US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Department of Veterans Affairs Care Assessment Needs (CAN) Primer. US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabrielian S, Yuan AH, Andersen RM, Rubenstein LV, Gelberg L. VA health service utilization for homeless and low-income Veterans: a spotlight on the VA Supportive Housing (VASH) program in greater Los Angeles. Med Care. 2014;52(5):454-461. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VHA Support Service Center Care Assessment Need (CAN) Score Report. Veterans Health Administration; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tierney M, Finnell DS, Naegle MA, LaBelle C, Gordon AJ. Advanced practice nurses: increasing access to opioid treatment by expanding the pool of qualified buprenorphine prescribers. Subst Abus. 2015;36(4):389-392. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1101733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hebert PL, Liu CF, Wong ES, et al. . Patient-centered medical home initiative produced modest economic results for Veterans Health Administration, 2010-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(6):980-987. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenheck RA, Neale MS, Mohamed S. Transition to low intensity case management in a VA Assertive Community Treatment model program. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2010;33(4):288-296. doi: 10.2975/33.4.2010.288.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elliott AC, Reisch JS Implementing a multiple comparison test for proportions in a 2xc crosstabulation in SAS® UT Southwestern Medical Center. Statistics and data analysis website. Accessed April 1, 2019. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi31/204-31.pdf

- 40.Conwell LJ, Cohen JW. Characteristics of Persons with High Medical Expenditures in the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population, 2002. Statistical Brief 73.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peikes D, Swankoski K, Mutti A, et al. . Evaluation of the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: Third Annual Report. Mathematica Policy Resarch; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peikes D, Anglin G, Dale S, et al. . Evaluation of the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: Fourth Annual Report. Mathematica Policy Research; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy A, Sessums L, Gupta R, et al. . Risk stratification methods and provision of care management services in comprehensive primary care initiative practices. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):451-454. doi: 10.1370/afm.2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothman AA, Wagner EH. Chronic illness management: what is the role of primary care? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):256-261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rich E, Lipson D, Libersky J, Parchman M. Coordinating Care for Adults with Complex Care Needs in the Patient-Centered Medical Home: Challenges and Solutions. White Paper (Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

- 46.Forrest CB, Glade GB, Baker AE, Bocian A, von Schrader S, Starfield B. Coordination of specialty referrals and physician satisfaction with referral care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(5):499-506. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.5.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis J, Hoyt A, Kakoza RM. Enhancing quality of primary care using an ambulatory ICU to achieve a patient- centered medical home. J Prim Care Community Health. 2011;2(4):234-239. doi: 10.1177/2150131911410063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hochman M, Asch SM. Disruptive models in primary care: caring for high-needs, high-cost populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):392-397. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3945-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong C, Siegel A, Ferris T. Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: What Makes for a Successful Care Management Program? Commonwealth Fund; 2014:1-19. [PubMed]

- 50.Meredith LS, Azhar G, Okunogbe A, et al. . Primary care providers with more experience and stronger self-efficacy beliefs regarding women veterans screen more frequently for interpersonal violence. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(5):586-591. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bastian LA, Trentalange M, Murphy TE, et al. . Association between women veterans’ experiences with VA outpatient health care and designation as a women’s health provider in primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(6):605-612. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cordasco KM, Zuchowski JL, Hamilton AB, et al. . Early lessons learned in implementing a women’s health educational and virtual consultation program in VA. Med Care. 2015;53(4)(suppl 1):S88-S92. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Ezeji-Okoye SC, et al. . Effect of an intensive outpatient program to augment primary care for high-need veterans affairs patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):166-175. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bodenheimer T. Strategies to Reduce Cost and Improve Care for High-utilizing Medicaid Patients: Reflections on Pioneering Programs. Center for Health Care Strategies Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1156-1166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301(6):603-618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finkelstein A, Zhou A, Taubman S, Doyle J. Health care hotspotting: a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(2):152-162. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1906848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Malley AS, Rich EC, Shang L, et al. . New approaches to measuring the comprehensiveness of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(2):356-366. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):766-772. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, Wulu J, Regan J, Politzer R. The relationship between primary care, income inequality, and mortality in US States, 1980-1995. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(5):412-422. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.5.412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parchman ML, Culler SD. Preventable hospitalizations in primary care shortage areas: an analysis of vulnerable Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8(6):487-491. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.6.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reschovsky JD, Ghosh A, Stewart K, Chollet D. Paying More for Primary Care: Can It Help Bend the Medicare Cost Curve? Commonwealth Fund; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoon J, Chow A, Rubenstein LV. Impact of medical home implementation through evidence-based quality improvement on utilization and costs. Med Care. 2016;54(2):118-125. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoon J, Rose DE, Canelo I, et al. . Medical home features of VHA primary care clinics and avoidable hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1188-1194. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2405-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Starfield B, Lemke KW, Bernhardt T, Foldes SS, Forrest CB, Weiner JP. Comorbidity: implications for the importance of primary care in ‘case’ management. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(1):8-14. doi: 10.1370/afm.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adams J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1032-1036. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. . Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2199-2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen AH, Murphy EJ, Yee HF Jr. eReferral: a new model for integrated care. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2450-2453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care: creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173-1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37(4):768-780. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9527-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oliver A. The Veterans Health Administration: an American success story? Milbank Q. 2007;85(1):5-35. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00475.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Smith B, et al. . Program Evaluation of VHA Mental Health Services Capstone Report. RAND Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu CF, Batten A, Wong ES, Fihn SD, Hebert PL. Fee-for-service Medicare-enrolled elderly veterans are increasingly voting with their feet to use more VA and less Medicare, 2003-2014. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 3):5140-5158. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Care Assessment Needs (CAN) 2.0 Model Coefficients, Odds Ratios, and Associated 95% Confidence Intervals for Hospitalization 90-Day Model

eTable 2. ICD-9 Codes for Selected Medical and Behavioral Conditions

eTable 3. Average Number of VHA Ambulatory Encounters Over One Year Among High-Risk Patients, by Primary Care Settinga (October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016)

eTable 4. Average Number of VHA Ambulatory Encounters Over One Year Among High-Risk Patients Alive Throughout VHA Fiscal Year 2016, by Primary Care Settinga (October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016)

eTable 5. Receipt of Any Add-On Intensive Services by Primary Care Type Among High-Risk Patients Alive Throughout VHA Fiscal Year 2016 (October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016)