Abstract

Background

Aedes albopictus has a well-established presence in southern European countries, associated with recent disease outbreaks (e.g. chikungunya). Development of insecticide resistance in the vector is a major concern as its control mainly relies on the use of biocides. Data on the species’ resistance status are essential for efficient and sustainable control. To date the insecticide resistance status of Ae. albopictus populations from Greece against major insecticides used in vector control remains largely unknown.

Methods

We investigated the insecticide resistance status of 19 Ae. albopictus populations from 11 regions of Greece. Bioassays were performed against diflubenzuron (DFB), Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis (Bti), deltamethrin and malathion. Known insecticide resistance loci were molecularly analysed, i.e. voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) mutations associated with pyrethroid resistance; presence and frequency of carboxylesterases 3 (CCEae3a) and 6 (CCEae6a) gene amplification associated with organophosphate (OP) resistance and; chitin synthase-1 (CHS-1) for the possible presence of DFB resistance mutations.

Results

Bioassays showed full susceptibility to DFB, Bti and deltamethrin, but resistance against the OP malathion (range of mortality: 55.30–91.40%). VGSC analysis revealed a widespread distribution of the mutations F1534C (in all populations, with allelic frequencies between 6.6–68.3%), and I1532T (in 6 populations; allelic frequencies below 22.70%), but absence of V1016G. CCE gene amplifications were recorded in 8 out of 11 populations (overall frequency: 33%). Co-presence of the F1534C mutation and CCEae3a amplification was reported in 39 of the 156 samples analysed by both assays. No mutations at the CHS-1 I1043 locus were detected.

Conclusions

The results indicate: (i) the suitability of larvicides DFB and Bti for Ae. albopictus control in Greece; (ii) possible incipient pyrethroid resistance due to the presence of kdr mutations; and (iii) possible reduced efficacy of OPs, in a scenario of re-introducing them for vector control. The study highlights the need for systematic resistance monitoring for developing and implementing appropriate evidence-based control programmes.

Keywords: Diagnostic, Bioassay, Arbovirus, Vector control, Mosquito tiger, Insecticide resistance, kdr, Bti, Gene amplification

Introduction

In the last two decades southern European countries have suffered from a number of vector-borne diseases (VBDs), such as chikungunya (CHIKV), dengue (DENV) and West Nile virus (WNV) outbreaks [1, 2]. This has been attributed to several factors including the introduction and establishment of invasive vector species, associated with the ongoing environmental and climate change and the globalization of human activities [3].

Aedes albopictus is an important vector and invasive mosquito species. Originating from the tropical and subtropical regions of southern Asia, it currently displays a worldwide distribution [4] facilitated by its ecological plasticity, competitive behavior and egg diapause/dormancy behaviour during the winter period [5]. Aedes albopictus was first recorded in Europe in 1979 [6] and to date displays a wide-spread distribution in the Mediterranean region while also reported in northern European countries [7]. Being a competent vector of more than 22 arboviruses, including CHIKV and DENV [8], Ae. albopictus constitutes a major public health threat. Its presence in Europe has been associated with the local transmission of CHIKV in Italy (2007 and 2017) and southeastern France (2010 and 2014) and of DENV in France (2010, 2013–2015), Spain (2014–2016) and Croatia (2010) [1]. Furthermore, since 2016 more than 2400 imported Zika cases have been reported in Europe [9, 10], which in conjunction with the known distribution of Ae. albopictus and Zika vectorial capacity raises concerns for potential autochthonous Zika transmission [11].

Aedes albopictus has also been reported in Greece [12], a country witnessing consecutive WNV outbreaks since 2010, with the largest outbreak in 2018 resulting in a total of 316 human cases and 50 fatalities [13]. Although Culex pipiens has been implicated as the primary WNV vector in Greece [14], Ae. albopictus could potentially have a role in disease transmission, as a secondary vector [5, 15]. Apart from a major public health concern, Ae. albopictus causes an important biting nuisance problem, negatively affecting the quality of life and potentially acting as a discouraging factor for the tourist economy [16].

The prevention of mosquito-borne diseases (MBDs) relies to a great extent on vector control [17] and the utilization of synthetic insecticides [18]. In Europe, pyrethroids (e.g. permethrin, deltamethrin and alpha-cypermethrin) and the larvicides diflubenzuron (DFB) and pyriproxyfen are the main insecticides used to control adult and immature stage Aedes mosquitoes, respectively [18, 19]. In Greece, applications of Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti) and of the insect growth regulator (IGR) DFB compose the majority of the vector control interventions implemented in large-scale (regional level) control programmes [20]. Pyrethroid insecticides, including type I (non-alpha-cyano group, such as permethrin) and type II (alpha-cyano group, such as deltamethrin and alpha-cypermethrin) formulations, are registered and used in professional vector control programmes and for personal protection/household level applications [21]. A major issue associated with the intensive use of a limited number of insecticides in mosquito and agricultural pest control is the development of insecticide resistance [18]. Insecticide resistance has been reported in Ae. albopictus, yet a big knowledge gap remains in regards to the susceptibility status, geographical distribution, frequency and co-occurrence of resistance traits and underlying mechanisms in the vector populations. Bioassay experiments have recorded resistance to several insecticides including pyrethroids, DDT, temephos, malathion, etc. mainly in rural and urban central and southern Asian populations (e.g. from China, Thailand, Singapore and India), while only sporadic cases of resistance have been reported in Europe, America and western Africa [18].

The two insecticide resistance mechanisms reported so far in Aedes mosquitoes are (i) target-site resistance, involving mutations at the insecticide’s target site of action and (ii) metabolic detoxification, obtained through overexpression or conformational changes of enzymes involved in the metabolism of the insecticide [18, 22]. To date, five mutations in two loci of the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) gene; V1016G (valine to glycine), I1532T (isoleucine to threonine) and F1534C/L/S (phenylalanine to cysteine/leucine/serine), have been reported in Ae. albopictus populations from central and southeastern Asia, European Mediterranean countries, the USA and Brazil [18].

The involvement of these five mutations in insecticide resistance has been further examined by expressing the mutated VGSC channels in Xenopus eggs and investigating how their electrophysiological properties are affected in the presence of insecticides. All three mutations at position F1534 (F1534C/L and S), as well as the I1532T mutation have been shown to significantly reduce the channel’s sensitivity to type I but not to type II pyrethroids [23, 24]. The V1016G mutation also reduces the channel’s sensitivity mainly to permethrin and slightly to deltamethrin [23]. However, a synergistic effect has been reported in the presence of the triple mutant V1016G + F1534C + S989P (a third mutation identified in Ae. aegypti populations), which substantially reduced sensitivity to both permethrin and deltamethrin [25].

Pyrethroid resistance has also been correlated to CYP6P12 over-expression conferring increased metabolic detoxification [26]. Metabolic resistance to the larvicide temephos (OP) has been functionally associated with the upregulation of carboxylesterases CCEae3a and CCEae6a, due to gene amplification [27]. Aedes albopictus populations from Greece and Florida (USA) have been found to carry this CCEae3a gene amplification or the CCEae3a-CCEae6a co-amplification [28]. Regarding alternative insecticides, such as IGRs or Bti, no genotypic resistance data have been reported for Aedes mosquitoes, but three point mutations I1043M/L/F in the chitin synthase-1 (CHS-1) gene were recently identified in Cx. pipiens mosquitoes, conferring very high levels of resistance to the larvicide DFB [29–31].

The re-appearance of VBDs in Europe, the widespread distribution of Ae. albopictus in southern Europe, the sporadic information on the vectors’ insecticide resistance status and the need for evidence-based mosquito control programmes acting in advance of disease outbreaks, make the monitoring and analysis of the Ae. albopictus insecticide resistance traits a necessity [32]. Here, we analysed the insecticide resistance status in a number of Ae. albopictus populations from Greece, using bioassays and molecular genotyping assays targeting known resistance markers.

Methods

Study localities, sample collections and mosquito handling

Adult and immature stage Ae. albopictus mosquitoes were collected during the summer of 2017, 2018 and 2019, in a total of 19 urban and peri-urban localities in Greece, in the regions of Thessaloniki [33] and Rodopi (northern Greece), Attica and Argolida (central Greece), the Island of Chios (north-eastern Aegean Islands complex) [33], Patras and Kalamata (western Greece), the Island of Kefalonia (Ionian Islands complex) and Crete (Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion - southern Greece) (Fig.1, Table 1). The localities we selected to include in the analysis were chosen based on: their geographical location (in order to cover a large geographical area of Greece), the history of insecticide applications, previous insecticide resistance findings in other mosquito species and the availability of Ae. albopictus samples (mosquito collections/surveillance programmes).

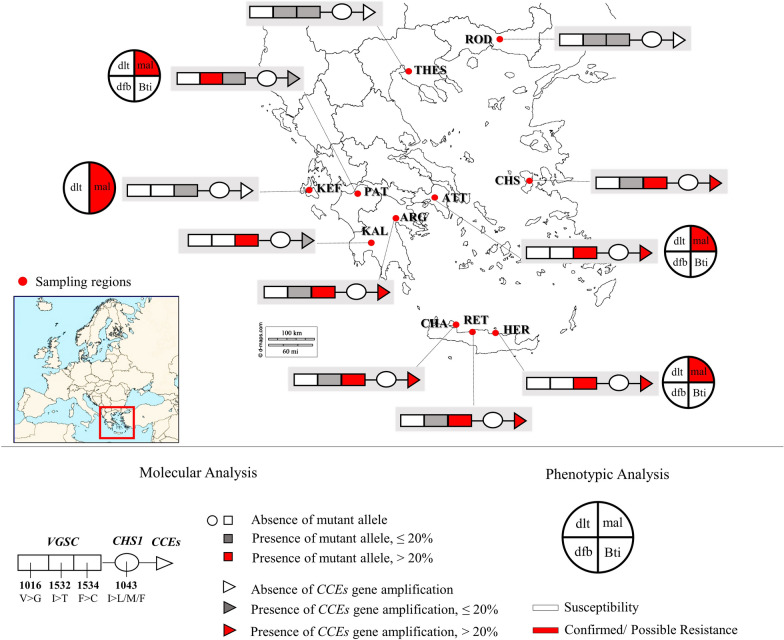

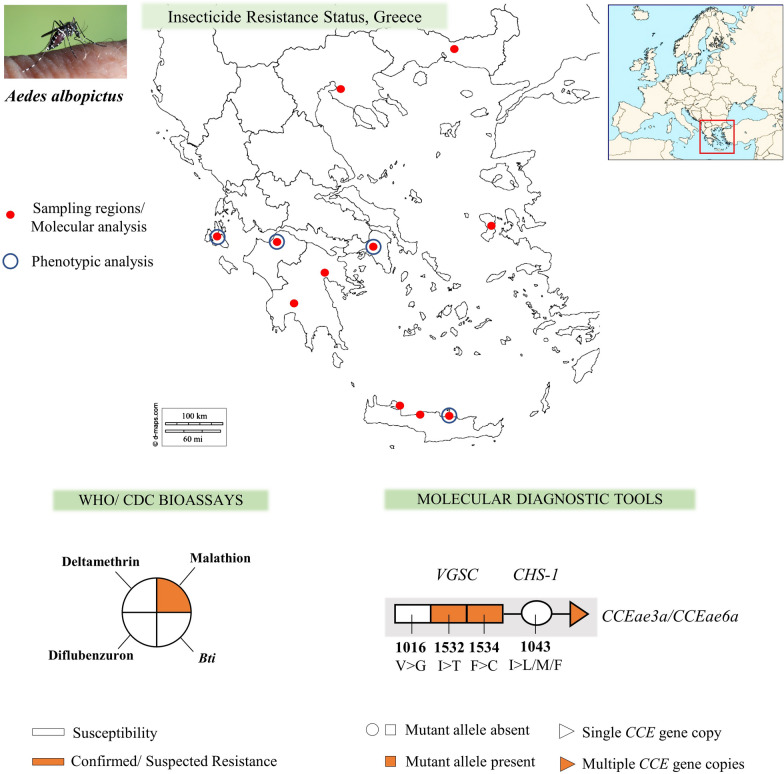

Fig. 1.

Aedes albopictus phenotypic and molecular analysis of insecticide resistance status, Greece. Sampling regions: ROD, Rodopi; THES, Thessaloniki; KEF, Kefalonia; PAT, Patras; ATT, Attica; CHS, Chios; KAL, Kalamata; ARG, Argolida; CHA, Chania; RET, Rethymno; HER, Heraklion. Molecular analysis includes the monitoring of: (i) mutations in the VGSC gene (substitutions in 3 loci: V1016G, I1532T and F1534C); (ii) mutations in the CHS-1 gene (substitution I1043L/M/F); and (iii) the presence of multiple CCEae3a and CCEae6a gene copies. Phenotypic analysis in a subgroup of populations includes: (i) CDC bottle bioassays in adult mosquitoes against deltamethrin (dlt) and malathion (mal) and (ii) WHO larval bioassays against Bti and diflubenzuron (dfb)

Table 1.

Aedes species composition per study site

| Region | Locality | Collection date | n | Ae. albopictus | Ae. cretinus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodopi | Iasmos | August 2018 | 14 | 14 | 0 |

| Thessaloniki | Thermi-Litsab | September 2018 | 30 | 30 | 0 |

| Refugee camp Diavatac | June 2017 | 10a | 10a | 0 | |

| Refugee camp Lagkadikiac | June 2017 | 18a | 18a | 0 | |

| Chios | Refugee camp Soudac | June 2017 | 23a | 23a | 0 |

| Attica | Aigaleo | August-September 2018 | 24 | 24 | 0 |

| Filothei | August-September 2018 | 14 | 14 | 0 | |

| Aghios Stefanos | October 2018 | 36 | 36 | 0 | |

| Aghios Eleftherios | October 2018 | 24 | 24 | 0 | |

| Kefalonia | Paliki | November 2019 | 45 | 45 | 0 |

| Patras | Rio | September 2019 | 33 | 33 | 0 |

| Argolida | Aghia Triada | August-September 2018 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Kilada | September 2018 | 57 | 57 | 0 | |

| Kalamata | Town | August 2018 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Chania | Town | September-October 2018 | 36 | 27 | 9 |

| Souda | August-October 2018 | 33 | 30 | 3 | |

| Rethymno | Town | August 2018 | 38 | 38 | 0 |

| Panormos | August-September 2018 | 18 | 18 | 0 | |

| Heraklion | Giofyro | June-July 2019 | 44 | 44 | 0 |

aIncludes 10 eggs analyzed as a pool

bThermi-Litsa is an organic farming locality

cSamples from Diavata, Lagkadikia and Souda refugee camps were collected and analysed in Fotakis et al. [33]

Abbreviation: n, total number of specimens analyzed per sampling region for species identification

Samples were collected every 2 weeks over a period of 1 or 2 months; a total of 3 to 7 collection events were conducted for each locality. Adult specimens were collected with mouth aspiration catches and CDC-light traps baited with dry ice. Larvae were sampled from natural and man-made/artificial containers with dipping collections and eggs were collected with oviposition traps (black plastic cups of 8 cm top diameter, 5 cm bottom diameter and 13 cm height; half covered with tap or rain water, with 2 wooden tongue depressors as oviposition substrate), baited with hay infusion and placed outdoors, amongst low vegetation, away from direct sunlight. Both larvae and eggs were collected from at least five different sites within each locality in order to avoid family bias and minimize the probability of including isofemale mosquitoes in the molecular analyses.

Following ovitrap collections, eggs were reared to adults in standard insectary conditions (temperature 27 ± 2 °C and relative humidity 70–80%), identified morphologically to species [34] and stored individually in absolute ethanol at 4 °C for the subsequent molecular analysis. A subgroup of eggs from the Aghios Stefanos locality (region of Attica; ovitrap collections from Aghios Stefanos were conducted in 2019, while samples analysed molecularly were collected in 2018), Kefalonia, Patras and Heraklion were reared to larvae or adults to use for susceptibility bioassays, as described below.

Genomic DNA extraction and molecular identification of mosquito species

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from individual larvae or adult mosquitoes and from pools of eggs (10 eggs per pool per locality; 3 localities), using DNAzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Species identification was based on the PCR amplification (KAPA Taq PCR Kit; KAPA Biosystems) of the nuclear ribosomal gene spacer ITS2, following an assay that discriminates between Ae. albopictus, Ae. cretinus and Ae. aegypti, by generating PCR products of 509 bp, 385 bp and 324 bp in length, respectively, as described in Patsoula et al. [35]; the 25 µl PCR reaction contained 1 µl gDNA, 2.5 µl of 10× DNA polymerase buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.4 µM of each primer (primers 5.8S and 28S [36]; Additional file 1: Table S1), 0.4 µM of dNTPs and 1.5 U of Taq polymerase. The applied thermal protocol was the following: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles × [denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, primer annealing at 52 °C for 1 min, primer extension at 72 °C for 1 min] and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.5% w/v agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

Insecticide susceptibility bioassays

Larval bioassays

Following the WHO guidelines for laboratory and field testing of mosquito larvicides [37], we examined the susceptibility of Ae. albopictus populations against two larvicides; the bacterial larvicide Bti (VectoBac12AS, Valent BioSciences LLC, Illinois, USA; 1200 ITU (international toxic units)/mg; 11.61% w/v) and the insect growth regulator DFB (DU-DIM 15SC, Arysta LifeScience, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 15% w/v). Both insecticides were diluted in distilled water. Bioassays were performed using Ae. albopictus third-early fourth-instar larvae (F0-F1 generation), reared under standard insectary conditions (temperature 27 ± 2 °C and relative humidity 70–80%). Fifteen to 20 larvae were placed in 99 ml water, to which 1 ml of the insecticide solution was added. Control bioassays contained 100 ml water. A range of 5 to 9 concentrations were tested for each insecticide (Bti: 0.008–0.500 mg/l; DFB: 0.0004–0.0200 mg/l) in order to define a mortality range between 10 and 95% and determine the LC50 and LC95 values. Three to 4 replicates were tested for each concentration. Larval mortality was recorded after the WHO recommended exposure time for each insecticide. Moribund larvae were counted as dead [37]. LC50 and LC95 values were estimated using the log-probit analysis Polo Plus 2.0 LeOra software (LeOra Software LLC, Parma, USA). Results were compared to the values reported for susceptible-laboratory Ae. albopictus strains in other studies [38–40].

Adult bioassays

Three to five day-old, non-blood fed female mosquitoes (F1–F2 generation) were subjected to insecticide susceptibility tests against deltamethrin and malathion, following the CDC bottle bioassay guidelines [41]. A Malaysian Ae. albopictus susceptible laboratory strain was included [42]. Both insecticides were purchased as technical grade material (PESTANAL® analytical standard; Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). Insecticide stock solutions were prepared in acetone and Wheaton bottles were cleaned and coated as described in the CDC guidelines. The diagnostic dose of the insecticide under evaluation was used: deltamethrin at 10 µg/bottle and malathion at 50 µg/bottle. Tests were performed using 20–25 mosquitoes per bottle. Four insecticide treated replicate bottles and at least one control bottle (coated with acetone only) were used in each experiment set. The diagnostic time for both insecticides tested was 30 min [41]. Alive and dead mosquitoes in each bottle were recorded at time intervals of 5–15 min. The insecticide susceptibility status was determined by the mortality rate at the diagnostic time, according to CDC recommendations: 98–100% mortality at the diagnostic time indicates susceptibility; 80–97% suggests the possibility of resistance that requires further confirmation; and mortality < 80% denotes resistance. In cases where mortality (between 3–5%) was recorded in the control bottles at the 2 h timepoint, mortality data were corrected using Abbott’s formula.

Genotyping of target site resistance mutations

Detection of knock-down resistance (kdr) mutations in the VGSC gene

The VGSC domain II was investigated for the presence of the V1016G mutation and domain III for mutations I1532T and F1534L/S/C via PCR and product sequencing.

The PCR (KAPA Taq PCR Kit) for domain II was carried out in 25 µl containing 1.5 µl of mixed gDNA extracted individually from 5–8 Ae. albopictus samples of the same locality, 2.5 µl of 10× DNA polymerase buffer, 0.4 µM of each primer (primers kdr2F and kdr2R; Additional file 1: Table S1), 0.4 µM of dNTPs and 1.5 U of Taq polymerase. The PCR thermal conditions were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles × [denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, primer extension at 72 °C for 1 min] and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. A small amount of the PCR products (5 µl) was electrophoresed on a 1% w/v agarose gel to verify the presence of the correct size amplicon (500 bp), and the remaining amount was purified using the Nucleospin PCR & Gel Clean-Up Kit (Macherey Nagel) and sequenced using the Sanger method (CeMIA S.A., Larissa, Greece) with primer kdr2F. Sequences were analysed using the sequence alignment editor BioEdit 7.2.5 (https://bioedit.software.informer.com/7.2/).

The PCR for domain III was carried out in 25 µl containing 1.5 µl of gDNA from Ae. albopictus individuals, 2.5 µl of 10× DNA polymerase buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.3 µM of each primer (primersaegSCF7 and aegSCR7 [43]; Additional file 1: Table S1), 0.4 uM of dNTPs and 1.5 U of Taq polymerase. The thermal conditions of the PCR were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles × [denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 57 °C for 30 s, primer extension at 72 °C for 1 min] and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. The products were electrophoresed on a 1% w/v agarose gel and the specific 740 bp band was gel extracted and purified using the Nucleospin PCR & Gel Clean-Up Kit (Macherey Nagel, Dueren, Germany) and sequenced using the Sanger method (CeMIA S.A.) with primer aegSCR8. Sequences were analysed using the sequence alignment editor BioEdit 7.2.5.

Analysis of the CHS-1 1043 locus

Analysis of the CHS-1 I1043 locus, to identify possible conserved DFB resistance mutations found in other species [29, 31], was performed in pools of mixed gDNA extracted individually from 5–8 Ae. albopictus samples of the same locality. Available Ae. albopictus DNA samples from other countries [28] were included in the analysis and genotyped individually. A 350-bp fragment of the CHS-1 gene, spanning the 1043 locus (numbering based on Musca domestica genomic sequence) was amplified in a 25 µl PCR (KAPA Taq PCR Kit) containing 1.5 µl DNA, 2.5 µl of 10× DNA polymerase buffer, 0.4 µM of each primer (primers kkv F3 and kkv R3; Additional file 1: Table S1), 0.4 µM of dNTPs and 1.5 U of Taq polymerase. The thermal conditions were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles × [denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, primer extension at 72 °C for 1 min] and final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. A small amount of the PCR products was electrophoresed on a 1.5% w/v agarose gel containing ethidium bromide to verify amplification. The remaining amount of the PCR products was purified using the Nucleospin PCR & Gel Clean-Up Kit (Macherey Nagel) and sequenced using the Sanger method (CeMIA S.A.) with the kkv F3 primer. Sequences were analysed using the sequence alignment editor BioEdit 7.2.5.

Metabolic resistance: detection of esterase gene amplification

CCEae3a and CCEae6a gene copy numbers were determined using quantitative real-time PCR on individual Ae. albopictus specimens. Amplification reactions at a 10 µl final volume were performed on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) containing 0.5 µl of gDNA, 0.2 µM of each primer (CCEae3aF, CCEae3aR, CCEae6aR and CCEEae6aF; Grigoraki et al. [28]; Additional file 1: Table S1) and SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, California, USA). Histone 3 (GenBank: XM_019687528.2) was used as a reference gene for normalization (primers His3 TaqF and His3 TaqR; Additional file 1: Table S1). The thermal parameters were: 50 °C for 2 min; 95 °C for 2 min, and 40 cycles × [95 °C for 3 s, 60 °C for 30 s]. Melting curves were performed for reference and target genes to verify the presence of a unique specific PCR product, which was checked on a 1% w/v agarose gel. A no-template control was included to detect possible contamination. Two replicates per sample were included. CCEae3a and CCEae6a gene copy numbers were estimated relatively to a temephos susceptible Αe. albopictus laboratory strain from Greece.

Results

Molecular identification of mosquito species

A total of 482 individual mosquitoes (larvae and adults) and 30 eggs (in pools) were identified to species by PCR discrimination of the ITS2 genomic sequence length; 97.6% of the samples were identified as Ae. albopictus, while only 12 specimens, all from Chania, Crete, were identified as Ae. cretinus (corresponding to 17.4% of the Chania population) (Table 1). No Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were recorded.

Insecticide susceptibility bioassays

Larval bioassays

Aedes albopictus populations from Aghios Stefanos-Attica (ATT), Patras and Heraklion, were tested for Bti resistance and found to be susceptible (Fig. 1). The calculated LC50 values were below 0.20 mg/l (corresponding to less than 0.240 ITU/ml) for all populations (Table 2), which is less than the LC50 values reported for susceptible Ae. albopictus laboratory strains in other studies. Indicatively, in Li et al. [39] and Su et al. [40], the reported LC50 values of the control susceptible strains were 0.036 mg/l and 0.044 mg/l, respectively (Bti formulation 7000 ITU/ mg).

Table 2.

WHO bioassay mortalities for Ae. albopictus populations tested against Bti

| Bti | Population | n | LC50 (95% CI) | LC95 (95% CI) | Slope ± SE | χ2 | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/l | ITU/ml | mg/l | ITU/ml | ||||||

| 1200 ITU/mg | Patras | 250 |

0.130 (0.080–0.171) |

0.156 (0.096–0.205) |

0.356 (0.250–0.994) |

0.427 (0.300–1.193) |

3.76 ± 0.45 | 113.3 | 23 |

| A. Stefanos- ATT | 301 |

0.195 (0.156–0.235) |

0.234 (0.187–0.282) |

0.465 (0.360–0.736) |

0.547 (0.432–0.883) |

4.39 ± 0.41 | 88.59 | 28 | |

| Heraklion | 243 |

0.145 (0.113–0.179) |

0.174 (0.136–0.215) |

0.383 (0.276–0.874) |

0.459 (0.331–1.049) |

3.90 ± 0.49 | 75.46 | 23 | |

| 7000 ITU/mg | Susceptible laboratory strains | ||||||||

| Li et al. [39] |

0.036 (0.028–0.047) |

0.252 (0.196–0.329) |

|||||||

| Su et al. [40] |

0.044 (0.040–0.050) |

0.308 (0.280–0.350) |

|||||||

Abbreviations: ATT, Attica region; n, total number of larvae tested to a range of insecticide concentrations; LC50, lethal concentration (mg/l) that kills 50% of the population; LC90, lethal concentration (mg/l) that kills 95% of the population, CI, confidence intervals; ITU, international toxic units; χ2, Chi-square testing linearity of dose-mortality response with degrees of freedom (df); df, degrees of freedom

Notes: Log-dose probit-mortality data for larvicides tested against Ae. albopictus larvae. The results are compared to the susceptible laboratory Ae. albopictus control strains of other studies [39, 40]

All three populations were also tested for diflubenzuron resistance and showed mortality of 100% in DFB doses below 0.02 mg/l. This is remarkably lower than the recommended field doses (DU-DIM 15SC: 0.32–0.63 mg/l), the recommended WHO dosage of DFB in potable water containers (0.25 mg/l) [44], as well as the emergence inhibition dose (EI50 of 0.376 mg/l) previously reported for susceptible Ae. albopictus field strains [38].

Adult bioassays

Aedes albopictus populations from Aghios Stefanos-Attica (ATT), Kefalonia, Patras and Heraklion were susceptible to deltamethrin (Fig. 1), as the mortality recorded at the 30 min diagnostic time was 100% (Table 3, Additional file 2: Figure S1). On the other hand, populations from Aghios Stefanos-Attica (ATT), Kefalonia and Heraklion, were resistant to malathion, displaying approximately 55% mortality at the diagnostic time (30 min), while the Patras population had a mortality of 91.4%, indicating possible resistance (Table 3, Additional file 2: Figure S1).

Table 3.

CDC bottle bioassay mortalities for Ae. albopictus populations tested against deltamethrin (pyrethroid) and malathion (OP)

| Population | Deltamethrin 10 µg/ml | Malathion 50 µg/ml | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n1 | Mortality (%) (95% CI) | Status | n2 | Mortality (%) (95% CI) | Status | |

| A. Stefanos-ATT | 75 | 100 (–) | S | 79 | 55.70 (28.55–82.85) | R |

| Patras | 70 | 100 (–) | S | 83 | 91.4 (83.10–99.70) | Ra |

| Kefalonia | 88 | 100 (–) | S | 83 | 55.6 (15.15–96.05) | R |

| Heraklion | 78 | 100 (–) | S | 78 | 55.3 (33.70–76.90) | R |

| Susceptible LC | 70 | 100 (–) | S | 76 | 100 (–) | S |

aPossibility of resistance

Notes: Mortality percentages correspond to the discriminating exposure time DT=30 min for both insecticides [40]. The average values of four insecticide treated replicate bottles are presented. n1 and n2 refer to the total number of female mosquitoes tested against deltamethrin and malathion, respectively

Abbreviations: ATT, Attica region; CI, confidence intervals; LC, laboratory colony; R, resistance; S, susceptibility (according to WHO recommendations for CDC bottle bioassay guidelines, 2010)

Genotyping of target site resistance mutations

VGSC: kdr mutations at positions V1016, I1532 and F1534

As the V1016G kdr mutation has never been recorded in Greece, pooled gDNA was used as a template for VGSC domain II amplification. Genotyping of the VGSC domain II was performed for a total of 323 larvae/adult mosquitoes (in 2–10 pools per region, depending on the number of specimens analysed per locality; 5–8 individuals per locality per pool) and 20 eggs (in pools of 10 per locality). The small number of specimens included per pool would enable the detection of any resistance allele upon sequencing. The wild type allele V1016 (codon GTA) was recorded in all cases (Fig. 1, Table 4).

Table 4.

Genotype and allele frequencies (%) of VGSC domain II locus V1016 and domain III loci I1532 and F1534

| Region | Year | V1016G | I1532T | F1534C | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | % allele freq | N2 | Genotype | % allele freq | Genotype | % allele freq | ||||||||

| (V) | II | IT | TT | (I) | (T) | FF | FC | CC | (F) | (C) | ||||

| Rodopi | 2018 | 13 | 100 | 12 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 95.8 | 4.2 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 83.3 | 16.7 |

| Thessaloniki | ||||||||||||||

| Diavata, Lagkadikiab | 2017 | 18a | 100 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 93.8 | 6.2 |

| Thermi-Litsa | 2018 | 30 | 100 | 30 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 96.7 | 3.3 | 26 | 4 | 0 | 93.3 | 6.7 |

| Chiosb | 2017 | 22a | 100 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 72.7 | 27.3 |

| Attica | 2018 | 59 | 100 | 52 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 31 | 31.7 | 68.3 |

| Kefalonia | 2019 | 45 | 100 | 41 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 37 | 1 | 3 | 91.5 | 8.5 |

| Patras | 2019 | 33 | 100 | 33 | 20 | 11 | 2 | 77.3 | 22.7 | 28 | 5 | 0 | 92.4 | 7.6 |

| Argolida | 2018 | 21 | 100 | 21 | 19 | 2 | 0 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 54.8 | 45.2 |

| Kalamata | 2018 | 7 | 100 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 58.3 | 41.7 |

| Rethymno | 2018 | 20 | 100 | 30 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 98.3 | 1.7 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 51.7 | 48.3 |

| Chania | 2018 | 31 | 100 | 31 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 93.5 | 6.5 | 15 | 14 | 2 | 71.0 | 29.0 |

| Heraklion | 2019 | 44 | 100 | 44 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 15 | 19 | 10 | 55.7 | 44.3 |

aIncludes 10 eggs analysed in a pool. Results are presented cumulatively for the different sampling localities in each region, except for Thessaloniki bSamples from Diavata and Lagkadikia refugee camps (Thessaloniki) and Chios were analysed in Fotakis et al. [33]

Abbreviations: N1 and N2, total number of genotyped specimens for VGSC domain II and domain III respectively, per sampling region; V, 1016V susceptible allele. Genotypes for VGSC locus 1016 are not given as all samples were wild-type 1016V/1016V; I, 1532I susceptible allele; T, 1532T mutant allele; II, 1532I/1532I homozygous; IT, 1532I/1532T heterozygote; TT, 1532T/1532T homozygous mutant; F, 1534F susceptible allele; C, 1534C mutant allele; FF, 1534F/1534F homozygous; FC, 1534F/1534C heterozygote; CC, 1534C/1534C homozygous mutant

For the detection of mutations I1532T and F1534C/L/S in the VGSC domain III, 319 individuals were genotyped. For the first time in Greece, the I1532T mutation was detected in 6 out of the 11 surveyed regions. Particularly, 23 genotyped specimens from Rodopi, Thessaloniki, Patras, Argolida, Rethymno and Chania were found to have this substitution, mostly in heterozygosis (genotype 1532I/1532T). In the majority of the above-mentioned regions, the mutant allele 1532T frequency was low, varying from 1.7 to 6.5% (Fig. 1). The highest frequency was observed in Patras (22.7%; the only 2 homozygotes 1532T/1532T were reported there) (Table 4).

The F1534C mutation was found in all regions. The regions with the highest 1534C allele frequency were Attica (68.3%), Argolida (45.2%), Rethymno (48.3%), Heraklion (44.3%) and Chania (29%), all located in central and southern Greece (we excluded Kalamata results due to the small number of specimens collected and analysed). In contrast, regions from northern Greece (Rodopi and Thessaloniki) and western Greece (Patras and Kefalonia) displayed lower 1534C allele frequencies, ranging between 6.6 and 16.7% (Fig. 1). The F1534C mutation appeared mainly in heterozygosis, with the exception of Attica, where more than half of the genotyped specimens were homozygous for the mutation (genotype 1543C/1534C) (Table 4). Only two individuals (sampled from Argolida and Patra) harboured both mutations, I1532T and F1534C, in heterozygosis (genotype 1532I/1532T; 1534F/1534C).

Chitin synthase (CHS-1): mutations at position I1043

The CHS-1 genomic sequence of 325 Ae. albopictus mosquitoes (in 2–10 pools per region, depending on the number of specimens analysed per locality; 5–8 individuals per locality per pool) and a total of 20 eggs (in pools of 10 per locality) were analysed for the presence of either of the three mutations I1043L/M/F, previously linked to DFB resistance. No mutations were detected (Fig.1, Additional file 1: Table S2). Likewise, no mutations were recorded in the 178 genotyped samples from USA, Brazil, Belize, Gabon, Switzerland, Taiwan, France, Mexico, China, Sri Lanka, Australia, Japan, Lebanon and Bangladesh (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Esterase gene amplification

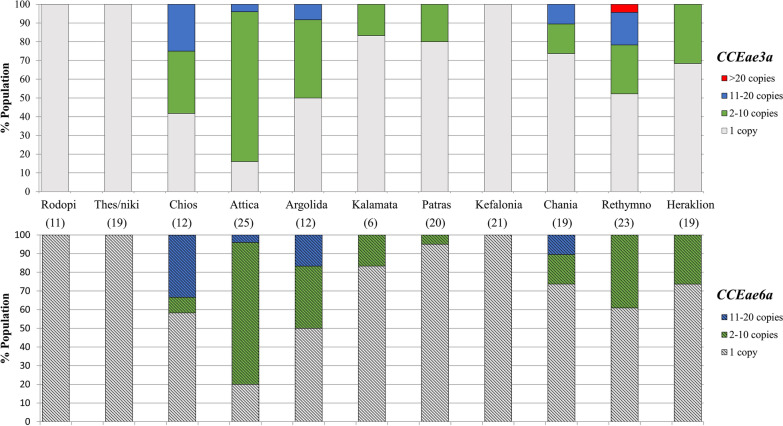

CCEae3a and CCEae6a amplification associated with temephos resistance was recorded in 8 out of the 11 surveyed regions in Greece (Fig. 1). Two types of amplification were found: a CCEae3a amplicon and a CCEae3a - CCEae6a co-amplicon.

Amplified esterase genes were detected in specimens from Chios, Argolida, Patra, Kalamata, Attica, Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion. The reported frequency of the CCeae3a amplification, in the eight locations, ranged from 16.6 to 84% and that of CCEae3a-CCEae6a co-amplification from 5 to 80%. The majority of samples with amplified esterases harboured between 2–10 gene copies. Individuals with more than 10 (11–20) and more than 20 gene copies (in the case of one individual from Rethymno) were also recorded. Attica was the region with the highest percentage of individuals carrying ≥ 2 copies of either CCEae3a or CCEae6a gene (84% and 80%, respectively) and Chios of individuals with > 10 copies (25% and 33.3%, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the relative CCEae3a and CCEae6a gene copy numbers in Aedes albopictus per sampling region. Solid bars (upper panel) refer to relative CCEae3a and patterned bars (lower panel) to relative CCEae6a gene copy numbers. Numbers in parentheses correspond to the number of specimens commonly analysed for both CCEs gene amplification with quantitative PCR. Results of each region presented are cumulative of different localities

No carboxylesterase gene amplification was detected in Rodopi, Thessaloniki and Kefalonia populations.

Discussion

This study represents an extended investigation of the insecticide resistance status of Ae. albopictus in Greece. Entomological monitoring revealed the dominant presence of Ae. albopictus over other Aedes container-breeding species and confirmed the species’ widespread distribution in the country [12, 45]. The discrimination of Ae. albopictus from morphologically similar Stegomyia species using the nuclear ITS2 as a molecular marker [35] is of high importance in order to distinguish this species from the primary arbovirus vector Ae. aegypti [46] and the non-vector Ae. cretinus [47]. The latter, although considered a native mosquito species in Greece [48] extensively reported in the past in Attica and Crete [45], was detected in our study only in Chania, Crete corresponding to an overall frequency of 2.4%. The absence/very low Ae. cretinus frequency in the sampled urban and peri- urban settings may be correlated to the competitive and highly adaptable behavior displayed by Ae. albopictus [49].

The Ae. albopictus WHO and CDC bioassays showed full susceptibility of the tested populations against deltamethrin and the larvicides DFB and Bti, suggesting their current suitability for inclusion in vector control programmes in Greece. On the contrary, mortality levels < 90% were recorded in the malathion assays indicating resistance against this OP insecticide. Although malathion and OPs are not currently used in Greece for mosquito control, OPs are still used in agriculture and thus possibly maintain a selection pressure also against Ae. albopictus. Alternatively, the fitness cost of the CCE amplification may be negligible, to allow a decrease in OP resistance. Nevertheless, the observed resistance raises some level of concern, regarding the potential need for re-introducing OP insecticides, in case of public health emergency.

Genotyping of the VGSC gene for the detection of mutations associated with pyrethroid resistance revealed a widespread distribution of the kdr mutation F1534C across the country, following initial reports of the mutation in Greece [50, 51]. The recorded 1534C allele frequencies were above 40% in populations from southern and central Greece, peaking in Attica (68.3%). Previous studies also report relatively high mutation frequencies (reaching 66%) in populations sampled from the Attica region [50, 51]. To date, kdr F1534C has also been recorded in Brazil [52], Singapore, Vietnam [53] and China [54], while other substitutions in the same genomic locus, F1534L and F1534S, also associated with pyrethroid resistance, have been identified in the USA, China, Vietnam and Italy [50, 53–55].

The involvement of both F1534L and F1534S mutations in resistance to type I pyrethoids was recently further supported by in vitro functional characterization data [24]. The F1534L substitution was shown to confer similar levels of insensitivity to the previously characterized F1534C, while F1534S seemed to have an even bigger effect. Thus, monitoring the presence of these mutations in countries, like Greece, where type I pyrethroids are used for vector control is of great importance.

The F1534C mutation in the homozygous state has been associated with resistance to permethrin [23] in Aedes mosquitoes. In the analysed populations, F1534C was observed mainly in heterozygosis, potentially accounting for low resistance levels, due to the recessive nature of the mutant 1534C allele [56]. Nevertheless, the recorded mutation frequencies should not be undermined, as a notable raise of insecticidal pressure may lead to rapid increase in mutation selection potentially hampering the effectiveness of permethrin based applications for Ae. albopictus control. Additionally, the investigation of P450s-mediated pyrethroid detoxification, which in combination with target-site mutations has been shown to confer operationally significant resistance levels [57], would be critical complementary evidence facilitating the development of efficient control programmes.

Another mutation in the VGSC gene, I1532T, was found in Greece at low frequencies (< 10%) in several surveyed regions with the exception of Patras (western Greece) where the mutant allele reached a frequency of 22.7%. This mutation has also been reported at considerable frequencies in Ae. albopictus populations from Italy [50, 51], Albania [51] and China [54]. Although Kasai et al. [53] demonstrated a lack of association between this mutation and resistance to pyrethroids, a recent study revealed that VGSC channels carrying this mutation have reduced sensitivity to type I pyrethoids, notably at similar levels to channels harbouring the F1534S mutation [24]. Therefore, it is important to monitor the presence and distribution of this mutation in field populations. We also identified in our samples two individuals carrying both the I1532T and F1534C mutations. In some cases, mutation co-occurrence can have an additive or even synergistic effect resulting in very high levels of resistance [22]. Although the co-occurrence of I1532T + F1534C has not yet been functionally characterized, the co-occurrence of I1532T with F1534S or F1534L was recently shown to have a similar effect as the single mutants in conferring type I pyrethroid insensitivity [24].

The V1016G kdr mutation, correlated with “stronger” resistance (than F1534C) to type I and type II pyrethroids [23, 53] was not detected in any of the analysed samples from Greece. However, it was recently recorded in Ae. albopictus populations from Hanoi (Vietnam), in Beijing (China) and across Italy [51, 53, 58]. The systematic monitoring of this mutation in Ae. albopictus populations from Greece and elsewhere is strongly recommended, given the primary role of pyrethroids in Aedes mosquito control worldwide [18] and the possibility of low mutation frequencies and/or focal mutation distribution going undetected.

Resistance to DFB was assessed molecularly in specimens from all 11 surveyed regions in Greece through monitoring of the substitutions I1043L/M/F in the CHS-1 gene, associated with high resistance levels in Cx. pipiens mosquitoes [29–31]. No CHS-1 mutations were recorded, a result in line with the respective bioassay outcome, indicating the effectiveness of DFB for Ae. albopictus control in the study regions. Likewise, all samples analysed from France, Switzerland, Lebanon, Belize, Gabon, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, China, Japan, Australia, Bangladesh, USA, Brazil and Mexico were homozygous for the wild type (susceptible) I1043 allele, indicating that this resistance mechanism is likely not yet present in Ae. albopictus worldwide. However, the possibility of a focal DFB resistance pattern, in line with Cx. pipiens findings [30] cannot be excluded, emphasizing the need for incorporating systematic monitoring of DFB resistance mutations in integrated Ae. albopictus surveillance programmes.

Carboxylesterase CCEae3a and CCEae6a gene amplifications linked to temephos resistance [27, 28] were detected in 8 out of the 11 surveyed regions. Almost 33% of the total Ae. albopictus specimens analysed, the majority of which were sampled from central and southern Greece, carried more than 1 copy of CCEae3a or both CCEae3a-CCEae6a genes indicating elevated temephos detoxification.

Interestingly out of the 156 Ae. albopictus samples commonly analysed for the detection of the F1534C kdr mutation and CCEae3a amplification, 25% were found to harbor both mutations, denoting a potential risk for multi-resistance against pyrethroid and organophosphate insecticides.

The observed resistance against malathion may be associated with the high occurrence of amplified CCEs in the analysed populations. CCEae3a and CCEae6a gene amplification was originally associated with temephos resistance in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes [27], yet Marcombe et al. [59] also correlated the presence of multiple CCEae3a gene copies with malathion resistance in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. Thus, it is possible that the detected CCEs amplifications in the Greek Ae. albopictus populations are responsible for the resistance levels recorded in the malathion bioassays, by conferring cross-resistance across additional OPs.

Evident differences were noted in the frequency of the F1534C kdr mutation, between populations from Thessaloniki (northern Greece; mutant F1534C allele frequency < 7%) and sampling locations in central and southern Greece (mutant F1534C allele frequencies > 29%). Although we cannot exclude the scenario of the passive transportation of populations harbouring insecticide resistance mutations, these differences may also partially reflect the imposed insecticidal pressures. Similarly, in Thessaloniki CCEs gene amplification was not detected in any sample, while 26–84% of the Attica, Argolida, Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion populations had more than one CCEae3a gene copy. The surveyed regions of central and southern Greece have intense agricultural activities, where pyrethroids and OPs have been used extensively for pest control over the years, possibly contaminating nearby Ae. albopictus breeding sites and leading to the selection of the respective resistance mutations [60]. On the contrary, in Thessaloniki the majority of the specimens were sampled from an organic farm (Litsa-Thermi) where no insecticides have been applied over the last ten years possibly explaining the low kdr mutation frequency and the absence of CCEs amplification.

The limited number of approved insecticides for public health purposes and the worldwide data on Ae. albopictus insecticide resistance generated to date raise concerns regarding the effectiveness and suitability of the current vector control interventions. Our findings significantly enrich the available information on Ae. albopictus insecticide resistance status. In a context of evidence-based vector control programmes, regular investigation of the species composition, population dynamics and systematic resistance monitoring encompassing both bioassays and molecular diagnostics, providing highly complementary yet not redundant information, are critical components for the development of resistance management strategies.

Conclusions

This study delineates the susceptibility profile of Ae. albopictus populations from Greece against commonly used insecticides. Our findings suggest the suitability of the larvicides DFB and Bti and the current effectiveness of pyrethroids for Ae. albopictus control. However, the presence of high kdr mutation frequencies raises concerns, given the dominant role of pyrethroids in mosquito control and the few alternative synthetic compounds available for public health purposes. The OPs malathion and temephos appear unreliable alternative insecticides for possible future re-introduction in mosquito control. Systematic monitoring of the insecticide resistance traits is imperative for the development of resistance management programmes ensuring the sustainability of the current chemical control tools.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used in this study for regular and real-time PCR. Table S2. Genotype and allele frequencies of the CHS-1 locus 1043, Greece. Table S3. Genotype and allele frequencies of the CHS-1 locus 1043, other countries.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. CDC bioassay mortality percentages corresponding to exposure time against malathion and deltamethrin for Aedes albopictus populations from Greece.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Bti

Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis

- CCE

carxoxylesterase

- (E)CDC

(European) Centre for Disease Control

- CHIKV

chikungunya virus

- CHS-1

chitin synthase-1

- CI

confidence interval

- CYP

cytochrome P450 monooxygenase

- DDT

dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane

- DENV

dengue virus

- df

degrees of freedom

- DFB

diflubenzuron

- EI

emergence inhibition

- GCN

gene copy number

- gDNA

genomic DNA

- IGR

insect growth regulator

- ITS2

internal transcribed spacer 2

- ITU

international toxic units

- LC

lethal concentration

- MBDs

mosquito-borne diseases

- OP

organophosphate

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SD

standard deviation

- VBDs

vector-borne diseases

- VGSC

voltage-gated sodium channel

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WNV

West Nile virus

Authors’ contributions

SB conducted the majority of molecular and bioassay analyses and made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data and manuscript preparation. EAF conducted molecular and bioassay analyses and contributed to the design of the work, interpretation of the data generated and manuscript preparation. IK made substantial contributions in the sample collection and bioassay experiments. LG contributed in the molecular analyses and manuscript preparation. SM provided samples for analysis. AC provided samples for analysis and contributed in data interpretation and manuscript revisions. JV made substantial contributions to the design of the work, interpretation of data and substantively revised the work/manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (GSRT) and the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) in the context of the action “1st Proclamation of Scholarships from ELIDEK for PhD Candidates”. Research on this topic has also received funding by the Prefecture of Crete, Greece.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sofia Balaska, Email: sofia_balaska@imbb.forth.gr.

Emmanouil A. Fotakis, Email: bio1763@gmail.com

Ilias Kioulos, Email: kioulose@yahoo.ca.

Linda Grigoraki, Email: Linta.Grigoraki@lstmed.ac.uk.

Spyridoula Mpellou, Email: mpellous@yahoo.gr.

Alexandra Chaskopoulou, Email: andahask@gmail.com.

John Vontas, Email: vontas@imbb.forth.gr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13071-020-04204-0.

References

- 1.Gossner MC, Ducheyne E, Schaffner F. Increased risk for autochthonous vector-borne infections transmitted by Aedes albopictus in continental Europe. Euro Surveill. 2018;23:24. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.24.1800268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett AD. West Nile in Europe: an increasing public health problem. J Travel Med. 2018;25(1):tay096. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semenza JC. Forum on Microbial Threats; Board on Global Health; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Global Health Impacts of Vector-Borne Diseases: Workshop Summary. Washington: National Academies Press; 2016. Vector-borne disease emergence and spread in the European Union. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraemer MU, Sinka ME, Duda KA, Mylne AQ, Shearer FM, Barker CM, et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. eLife. 2015;4:e08347. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paupy C, Delatte H, Bagny L, Corbel V, Fontenille D. Aedes albopictus, an arbovirus vector: From the darkness to the light. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adhami J, Reiter P. Introduction and establishment of Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus Skuse (Diptera: Culicidae) in Albania. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1998;14:340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ECDC. Mosquito maps. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and European Food Safety Authority; 2019. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/surveillance-and-disease-data/mosquito-maps. Accessed 30 Jan 2019.

- 8.Gratz NG. Critical review of the vector status of Aedes albopictus. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:215–227. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ECDC. Zika virus infection. Annual epidemiological report for 2016. Stockholm; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2018. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER_for_2016-Zika-virus-infection.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2018.

- 10.ECDC. Zika virus infection. Annual epidemiological reports for 2017. Stockholm; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2019. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER_for_2017-Zika-virus-disease.pdf. Accessed 29 Jul 2019.

- 11.Jupille H, Seixas G, Mousson L, Sousa CA, Failloux AB. Zika virus, a new threat for Europe? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badieritakis E, Papachristos D, Latinopoulos D, Stefopoulou A, Kolimenakis A, Bithas K, et al. Aedes albopictus (Skuse, 1895) (Diptera: Culicidae) in Greece: 13 years of living with the Asian tiger mosquito. Parasitol Res. 2018;117(2):453–460. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5721-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West Nile virus in Greece. Annual epidemiological report for 2018. In: National Public Health Organization. H.C.D.C.P. 2018. https://eody.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Annual_Report_WNV_2018_ENG.pdf.

- 14.Mavridis K, Fotakis EA, Kioulos I, Mpellou S, Konstantas S, Varela E, et al. Detection of West Nile virus - lineage 2 in Culex pipiens mosquitoes, associated with disease outbreak in Greece, 2017. Acta Trop. 2018;182:64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortuna C, Remoli ME, Severini F, Di Luca M, Toma L, Bucci P, et al. Evaluation of vector competence for West Nile virus in Italian Stegomyia albopicta (=Aedes albopictus) mosquitoes. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:430–433. doi: 10.1111/mve.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolimenakis A, Bithas K, Latinopoulos D, Richardson C. On lifestyle trends, health and mosquitoes: formulating welfare levels for control of the Asian tiger mosquito in Greece. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson AL, Courtenay O, Kelly-Hope LA, Scott TW, Takken W, Torr SJ, et al. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0007831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moyes CL, Vontas J, Martins AJ, Ching Ng L, Ying Koou S, Dusfour I, et al. Contemporary status of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses infecting humans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellini R, Zeller H, Van Bortel W. A review of the vector management methods to prevent and control outbreaks of West Nile virus infection and the challenge for Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:323. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosquito control programs, action plan and relevant information and public precaution for the year 2020. In: Ministry of Health. https://www.moh.gov.gr/. Accessed 9 Mar 2020.

- 21.Κoliopoulos G, Kefaloudi C. Mosquitoes and their control in Greece. In: National Public Health Organization; 2018. https://eody.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/programma_katapolemisis_kounoupiwn.pdf.

- 22.Liu N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60:537–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Υ, Nomura Υ, Satar G, Hu Ζ, Nauen R, He SY, et al. Molecular evidence for dual pyrethroid-receptor sites on a mosquito sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Scie USA. 2013;110:11785–11790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305118110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong K, et al. Knockdown resistance (kdr) to pyrethroid insecticides. First International Molecular Plant Protection Congress (MPPC-2019), 10–13 April 2019, Adana, Turkey.

- 25.Hirata K, Komagata O, Itokawa K, Yamamoto A, Tomita T, Kasai S. A single crossing-over event in voltage-sensitive Na+ channel genes may cause critical failure of dengue mosquito control by insecticides. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishak IH, Riveron JM, Ibrahim SS, Stott R, Longbottom J, Irving H. The Cytochrome P450 gene CYP6P12 confers pyrethroid resistance in kdr-free Malaysian populations of the dengue vector Aedes albopictus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24707. doi: 10.1038/srep24707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigoraki L, Lagnel J, Kioulos I, Kampouraki A, Morou E, Labbé P, et al. Transcriptome profiling and genetic study reveal amplified carboxylesterase genes implicated in temephos resistance, in the Asian Tiger Mosquito Aedes albopictus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grigoraki L, Pipini D, Labbé P, Chaskopoulou A, Weill M, Vontas J. Carboxylesterase gene amplifications associated with insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus: geographical distribution and evolutionary origin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grigoraki L, Puggioli A, Mavridis K, Douris V, Montanari M, Bellini R, et al. Striking difubenzuron resistance in Culex pipiens, the prime vector of West Nile Virus. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12103-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porretta D, Fotakis EA, Mastrantonio V, Chaskopoulou A, Michaelakis A, Kioulos I, et al. Focal distribution of diflubenzuron resistance mutations in Culex pipiens mosquitoes from northern Italy. Acta Trop. 2019;193:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fotakis EA, Mastrantonio V, Grigoraki G, Porretta D, Puggioli A, Chaskopoulou A, et al. Identification and detection of a novel point mutation in the chitin synthase gene of Culex pipiens associated with diflubenzuron resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dusfour I, Vontas J, David JP, Weetman D, Fonseca DM, Corbel V, et al. Management of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses: advances and challenges. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fotakis EA, Giantsis IA, Castells Sierra J, Tanti F, Balaska S, Mavridis K, et al. Population dynamics, pathogen detection and insecticide resistance of mosquito and sand fly in refugee camps, Greece. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-0635-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker N, Petric D, Zgomba M, Boase C, Madon MB, Dahl C, Kaiser A. Mosquitoes and their control. 2. New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patsoula E, Samanidou-Voyadjoglou A, Spanakos G, Kremastinou J, Nasioulas G, Vakalis NC. Molecular and morphological characterization of Aedes albopictus in northwestern Greece and differentiation from Aedes cretinus and Aedes aegypti. J Med Entomol. 2006;43:40–54. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/43.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porter C, Collins FH. Species-diagnostic differences in a ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer from the sibling species Anopheles freeborni and Anopheles hermsi (Diptera: Culcidae) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:271–279. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO. Guidelines for laboratory and field testing of mosquito larvicides. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/69101.

- 38.Suter T, Crespo MM, de Oliveira M, de Oliveira TS, de Melo-Santos MA, de Oliveira CM, et al. Insecticide susceptibility of Aedes albopictus and Ae. aegypti from Brazil and the Swiss-Italian border region. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:431. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2364-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Xu J, Zhong D, Zhang H, Yang W, Zhou G, et al. Evidence for multiple-insecticide resistance in urban Aedes albopictus populations in southern China. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:4. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2581-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su X, Guo Y, Deng J, Xu J, Zhou G, Zhou T, et al. Fast emerging insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus in Guangzhou, China: alarm to the dengue epidemic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brogdon WG, Chan A. Guidelines for evaluating insecticide resistance in vectors using the CDC bottle bioassay. CDC technical report. Methods in Anopheles research, 2nd ed. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

- 42.Ishak IH, Jaal Z, Ranson H, Wondji CS. Contrasting patterns of insecticide resistance and knockdown resistance (kdr) in the dengue vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from Malaysia. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:181. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kasai S, Ng LC, Lam-Phua SG, Tang CS, Itokawa K, Komagata O, et al. First detection of a putative knockdown resistance gene in major mosquito vector, Aedes albopictus. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2011;64:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality 3rd edition incorporating 1st and 2nd addenda. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/fulltext.pdf.

- 45.Giatropoulos AK, Michaelakis AN, Koliopoulos GT, Pontikakos CM. Records of Aedes albopictus and Aedes cretinus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Greece from 2009 to 2011. Hell Plant Prot J. 2012;5:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souza-Neto JA, Powell JR, Bonizzoni M. Aedes aegypti vector competence studies: a review. Infect Genet Evol. 2019;67:191–209. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaffner F, Mathis A. Dengue and dengue vectors in the WHO European region: past, present, and scenarios for the future. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1271–1280. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70834-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edwards FW. A revision of the mosquitoes of the Palaearctic region. Bull Entomol Res. 1921;12:325–326. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giatropoulos A, Papachristos DP, Koliopoulos G, Michaelakis A, Emmanouel N. Asymmetric mating interference between two related mosquito species: Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus and Aedes (Stegomyia) cretinus. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu J, Bonizzoni M, Zhong D, Zhou G, Cai S, Li Y, et al. Multi-country survey revealed prevalent and novel F1534S mutation in voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) gene in Aedes albopictus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pichler V, Malandruccolo C, Serini P, Bellini R, Severini F, Toma L, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic pyrethroid resistance of Aedes albopictus, with focus on the 2017 chikungunya outbreak in Italy. Pest Manag Sci. 2019;75:2642–2651. doi: 10.1002/ps.5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aguirre-Obando OA, Martins AJ, Navarro-Silva MA. First report of the Phe1534Cys kdr mutation in natural populations of Aedes albopictus from Brazil. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:160. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2089-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Kasai S, Caputo B, Tsunoda T, Cuong TC, Maekawa Y, Lam-Phua SG, et al. First detection of a VSSC allele V1016G conferring a high level of insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus collected from Europe (Italy) and Asia (Vietnam), 2016: a new emerging threat to controlling arboviral diseases. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1700847. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.5.1700847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao JP, Chen HM, Shi H, Peng H, Ma YJ. Correlation between adult pyrethroid resistance and knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) field populations in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7:86. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0471-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marcombe S, Farajollahi A, Healy SP, Clark GG, Fonseca DM. Insecticide resistance status of United States populations of Aedes albopictus and mechanisms involved. PLoS One. 2014;9:e0004696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yanola J, Somboon P, Walton C, Nachaiwieng W, Prapanthadara L. A novel F1552/C1552 point mutation in the Aedes aegypti voltage-gated sodium channel associated with permethrin resistance. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2010;96:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fadel AN, Ibrahim SS, Tchouakui M, Terence E, Wondji MJ, Tchoupo M, et al. A combination of metabolic resistance and high frequency of the 1014F kdr mutation is driving pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles coluzzii population from Guinea savanna of Cameroon. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:263. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou X, Yang C, Liu N, Li M, Tong Y, Zeng X, et al. Knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations within seventeen field populations of Aedes albopictus from Beijing China: first report of a novel V1016G mutation and evolutionary origins of kdr haplotypes. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:180. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3423-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marcombe S, Fustec B, Cattel J, Chonephetsarath S, Thammavong P, Phommavanh N, et al. Distribution of insecticide resistance and mechanisms involved in the arbovirus vector Aedes aegypti in Laos and implication for vector control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caputo B, Ienco A, Cianci D, Pombi M, Petrarca V, Baseggio A, et al. The “auto-dissemination” approach: a novel concept to fight Aedes albopictus in urban areas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used in this study for regular and real-time PCR. Table S2. Genotype and allele frequencies of the CHS-1 locus 1043, Greece. Table S3. Genotype and allele frequencies of the CHS-1 locus 1043, other countries.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. CDC bioassay mortality percentages corresponding to exposure time against malathion and deltamethrin for Aedes albopictus populations from Greece.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.