Abstract

Biosynthesis of the hydroxamate siderophore aerobactin requires the activity of four proteins encoded within the iuc operon. Recently, we biochemically reconstituted the biosynthetic pathway and structurally characterized IucA and IucC, two enzymes that sequentially couple N6-acetyl-N6-hydroxylysine onto the primary carboxylates of citrate. IucA and IucC are members of a family of nonribosomal peptide synthetase-independent siderophore (NIS) synthetases that are involved in the production of other siderophores including desferrioxamine, achromobactin, and petrobactin. While structures of several members of this family have been solved, there is limited mechanistic insight into the reaction catalyzed by NIS synthetases. Therefore, we performed terreactant, steady state kinetic analysis, and herein provide evidence for an ordered mechanism in which chemistry is preceded by the formation of the quaternary complex. We further probed two regions of the active site with site-directed mutagenesis and identified several residues, including a conserved motif that is present on a dynamic loop, that are important for substrate binding and catalysis.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the ESKAPE organisms, a collection of human pathogens for which there is a critical need for new antibiotics. Recently, a hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKP) strain has also emerged that can infect otherwise healthy individuals and metastatically spread from the primary site of infection to a variety of secondary sites (1–3). While most hvKP strains are currently antibiotic sensitive, the development of multi-drug resistant hvKP strains through convergence of resistant and hypervirulence phenotypes is a looming threat (3). Many bacteria, including hvKP strains, produce elevated amounts of siderophores, small molecule chelators that are produced in low-iron environments (4, 5). While the correlation between the production of the hydroxamate siderophore aerobactin and virulence of K. pneumoniae was identified in the mid-1980s (6), recent genetic evidence has clearly demonstrated that of the four siderophores encoded within the hvKP genome aerobactin contributes most significantly to virulence (7, 8).

Motivated by the critical role that aerobactin plays in the pathogenicity of hvKP and other Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae, we have used structural, biochemical, and molecular tools to interrogate several of the aerobactin biosynthetic enzymes. The aerobactin biosynthetic operon contains four genes (9, 10), iucABCD, that are required for the production of aerobactin (Figure 1). The functions of the proteins were originally identified through sequence predictions and genetic studies, including analysis of pathway intermediates produced by mutant strains (11, 12). We recently reconstituted the enzymatic synthesis of aerobactin biochemically and through heterologous expression of all four genes in E. coli (13). Aerobactin biosynthesis requires the activities of the acetyltransferase IucD and the hydroxylase IucB to form N6-acetyl-N6-hydroxylysine (ahLys). Two molecules of the hydroxamate intermediate ahLys are then sequentially installed on the primary carboxylic acids of citrate by the activities of IucA and IucC to produce aerobactin. We also identified the high degree of stereoselectivity of the aerobactin synthetases by elucidating the stereochemistry of the monosubstituted citrate intermediate.

Figure 1. Aerobactin biosynthesis.

Aerobactin biosynthesis is catalyzed by four enzymes. A. IucD and IucB catalyze the sequential hydroxylation and acetylation of the N6 amino group of lysine to produce N6-acetyl-N6-hydroxylysine (ahLys). B. Two molecules of ahLys are then sequentially installed on the primary carboxylates of citrate to form aerobactin. C. The two-step reaction catalyzed by IucA involves the initial adenylation of citrate to form the citryl-AMP intermediate. This reacts in a second partial reaction with the α-amino group of ahLys to form the biosynthetic intermediate harboring a single ahLys adduct.

Many siderophores are produced by the modular nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) enzymes (5). In contrast, another class of siderophores, including desferrioxamine, petrobactin, achromobactin, staphyloferrin, and rhizoferrin (4, 14), are NRPS-independent siderophores (15, 16), or NISs, that are produced with different enzyme families. Common to the NIS biosynthetic pathways are NIS synthetases that catalyze a ligation between a carboxylate and nucleophile, most commonly an amine. The carboxylate is first activated by reaction with ATP to form an acyl-adenylate. The amine substrate then displaces AMP to form the product. The NIS synthetases share relatively low sequence homology, generally around 20–30%, reflecting the variation both the carboxylate and amine substrates. The NIS synthetases have been divided into three classes that depend on both sequence identity as well the carboxylate substrate. Type A enzymes utilize citrate, whereas type B enzymes react with α-ketoglutarate. Finally, type C NIS synthetases react with a citrate or succinate derivate (17). Six NIS synthetases have been structurally characterized including type A enzymes AcsD from the achromobactin biosynthetic pathway (18) and IucA from aerobactin biosynthesis (19). Additionally, type C enzymes whose structures have been determined include AlcC (20), AsbB (21), IucC (13), and DfoC (22), which are involved in the production of alcalignin, petrobactin, aerobactin, and desferrioxamine, respectively. Interestingly, DfoC exists as a fusion with a succinyltransferase domain. IucA, AsbB, and AlcC have all been crystallized in the presence of either ATP or ADP. The structural analysis of AcsD is the most comprehensive with six structures solved with combinations of bound nucleotide, citrate, and the product analog, citrylethylenediamine.

To supplement these structural studies, biochemical analyses of these and other NIS synthetases have employed mutagenesis to identify residues that influence the substrate specificity. Again, the most comprehensive analysis used the Type A protein AcsD that catalyzes the ligation of citrate and serine to form O-citryl-L-serine, which spontaneously rearranges to N-citryl-L-serine product (18). Two residues that interact with the citrate, Arg305 and His444, were both mutated resulting in enzymes with severely compromised activity. A follow up study further explored the residues that control selectivity of the nucleophile for the reaction (23). Additionally, several mutagenesis studies have explored the nucleophile specificity of the Type C enzymes, including AsbB of petrobactin biosynthesis (21), DesD of desferrioxamine biosynthesis (24), and Rfs of rhizoferrin biosynthesis (25).

Although a number of studies inform our understanding of the features of the active site that guide substrate binding, the catalytic mechanism of the terreactant NIS synthetase reaction has not been explored. The NRPS adenylation domains and the homologous acyl-CoA synthetases (26) carry out their complete reaction through a bi-uni-uni-bi ping pong reaction. Members of this family are commonly assayed via the exchange of radiolabeled pyrophosphate into ATP in the absence of a thiol nucleophile, demonstrating the kinetic independence of the first partial reaction. In contrast, the NIS synthetases do not catalyze pyrophosphate release or exchange in the absence of the nucleophile (19, 27). These observations led us to explore a more thorough kinetic understanding of the type A NIS synthetase IucA from K. pneumoniae.

Herein, we determine the terreactant kinetic mechanism through a series of experiments designed to probe the order of substrate addition. We further use site-directed mutagenesis guided by our previous hvKP IucA structures (19) to identify residues involved in ligand binding. Through these studies, we also identify a flexible loop containing a conserved motif that appears to be involved specifically in the binding of the native nucleophile for the IucA reaction.

Methods

Materials.

All materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified. All reagents were dissolved in Milli-Q purified water and 0.2 μm filtered.

Computational.

Sequence alignments of IucA protein sequences from manually annotated aerobactin operons were done with ENDscript (28). Protein structure diagrams were created with PYMOL (29, 30). Structural alignments for analysis were done with LSQKAB of the CCP4 suite of programs (31).

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of hvKP IucA WT and mutants.

The purification of hvKP IucA WT (NCBI Accession EMB09144) was performed as previously described (19). The purified plasmid of hvKP IucA WT was used as the template for site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent QuikChange II Kit). Primers affiliated with each mutant are listed in Table S2. The hvKP IucA mutants were purified in the same manner as WT (19). Specifically, BL21 DE3 E. coli (New England Biolabs) were grown at 37°C at 250 rpm until an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 was reached. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 500 μM and the temperature was lowered to 16°C at 250 rpm overnight. Cells were centrifuged and pellets were stored at − 80 °C until needed. Pellets were resuspended in 3 mL lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.2 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol) per gram of cell pellet, 1 mg lysozyme per mL lysis buffer, and ~ 2 mg DNase I at 4°C with stirring. After about 40 min of resuspension, cells were lysed by sonication: 10 min at 4°C, 50% amplitude, 30.0 sec on, 45.0 sec off. Insoluble material was cleared by centrifugation and the supernatant was loaded over a 5 mL HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), and eluted with lysis buffer containing 300 mM imidazole (elution buffer). Fractions that contained the protein as determined by SDS-PAGE were pooled and the polyhistidine affinity tag was cleaved by TEV protease in dialysis buffer, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM TCEP overnight at 4°C. The protein was clarified and loaded over the HisTrap HP column a second time and flow-through fractions were collected. Fractions containing IucA, as determined by SDS-PAGE, were concentrated (Amicon 50 kDa MWCO) and loaded onto a gel filtration column, Superdex-200 16/600 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM TCEP, pH 7.5. Fractions determined to be a tetramer compared to size exclusion standards were pooled and >95% pure based on SDS-PAGE.

Thermal Shift Assay of IucA with substrates and substrate analogs and IucA mutants.

A fluorescence-based thermal shift assay (32) as described previously (33), was used to determine if substrates were able to bind and thermally stabilize wild-type IucA and to compare the overall stability of wild-type and mutant IucA enzymes in the absence of ligands. Samples (30 μL, 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM TCEP, pH 7.5) were prepared containing 10 μg IucA, 5x SYPRO Orange dye, and various combinations of substrates and substrate analogues in 96-well PCR plates (Stratagene) sealed with polyolefin film. ATP, ATP analogues, and citrate were at included at 1.5 mM (≈10x KM), whereas ahLys was included at 5 mM (≈5.7x KM). The plate was placed in a Stratagene Mx3005P real-time PCR instrument and the temperature was increased from 25 to 99 °C over 45 min while the fluorescence intensity (λEX = 545 nm, λEM = 568 nm) was measured every 0.5 °. Melting temperatures (TM) were determined by calculating the maximum value of first derivative of the melting curves and are presented as three technical replicates. In addition to IucA substrates, ATP analogs adenosine-5’-α,β-methylene-triphosphate (AMPCPP), adenosine-5’-β,γ-methylene-triphosphate (AMPPCP), adenosine-5’-α,β-imido-triphosphate (AMPPNP), and adenosine-5’-o-3-thio-triphosphate (ATPγS) were also included.

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of YP IucA.

The gene sequence encoding the 590-residue IucA protein from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (YP IucA) was retrieved from the NCBI database (accession ABS46958). The iucA gene was synthesized by GenScript, Inc. in the pUC57 vector. The synthetic gene was incorporated into the pETDuet-1 plasmid at multiple cloning site MCS2 by restriction digest of Nde I and Xho I and subsequent ligation, whereby MCS1 was modified with an N-terminal 6xHis SUMO protein. The expression construct was verified by DNA sequencing analysis. The His6-tagged SUMO-YP IucA fusion protein was expressed from SHuffle DE3 competent E. coli cells (New England Biolabs) modified with Lemo21 plasmid (New England Biolabs). Cultures were grown in LB medium with 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol at 37°C (250 rpm) until an OD600 of 0.7 was achieved. The temperature was lowered to 16 °C and protein expression was induced with 400 μM IPTG. Cultures were incubated overnight at 250 rpm and 16 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended with 3 mL lysis buffer (50 mM MOPS, 250 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM TCEP, 10% glycerol, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) per g of cell paste, supplemented with 1 mg/mL hen egg white lysozyme, 0.5 mL general use protease inhibitor cocktail, and 10 μg/mL DNase I. Cells were agitated for 30 minutes at 4°C and lysed by sonication (10.0 minutes, 50% amplitude, 30.0 seconds on, 45.0 seconds off). The lysate was clarified by ultracentrifugation at 185 × 103 g. The supernatant was syringe filtered over a 0.45 μm polysulfone membrane before being applied to a 5 mL HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Following a wash with buffer containing 50 mM imidazole, the protein was eluted by a gradient of lysis buffer plus 300 mM imidazole. The His6-SUMO-YP IucA fusion protein eluted as one peak, and fractions shown to contain the fusion target protein by SDS-PAGE were combined in the presence of 12 mg/mL His6-ULP1 (SUMO protease) and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 3.5 L of 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.2 mM TCEP. Following SUMO protease cleavage, the dialyzed sample was spiked with imidazole to 20 mM. This solution was passed over the Ni2+-sepharose column a second time to remove the cleaved His6-SUMO tag as well as the protease. The flow-through fractions containing YP IucA were combined and concentrated using a 50,000 MWCO filter (Amicon Ultra-15) before size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The concentrated protein sample was eluted over an SEC column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using 20 mM MOPS, 75 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM TCEP, pH 7.5 at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Peak fractions were combined based on MW standards. The resulting YP IucA preparation was > 95% pure based on SDS-PAGE. YP IucA was concentrated to ~ 2 mg/mL and flash cooled in liquid N2 before being stored at −80°C for subsequent use.

NADH Consumption Assay.

An NADH consumption assay (34) was used to measure the activity of IucA. Briefly, this assay uses citrate and ATP to form citryl-adenylate, which then reacts with a nucleophile to yield the ligated product, as well as PPi, and AMP. In the coupled assay, the production of the AMP byproduct serves as a substrate for the enzyme-mediated oxidation of NADH to NAD+ using adenylate kinase (myokinase), pyruvate kinase, and ultimately lactate dehydrogenase. The continuous enzyme-coupled assay is observed spectrophotometrically at the NADH absorbance maximum of 340 nm (ε = 6220 M−1 cm−1). As reported previously, hydroxylamine was used as a surrogate nucleophile in some experiments to substitute for the synthetic reagent ahLys. Hydroxylamine is a small solvent-like molecule that is predicted to freely access the active site in a non-specific manner to attack the activated adenylate intermediate. For this reason, it was also employed for some mutant enzymes to confirm proper folding of enzymes and the ability to catalyze the first partial reaction. In instances where multiple protein preparations or multiple investigators repeated the same kinetic analyses, parameters were determined to vary by less than two- to three-fold.

Investigation of IucA activity using the NADH consumption assay was performed as previously published (19). To each well of a 96-well plate, a solution of enzyme was added to one side, and a solution of nucleophile to the other, avoiding contact. The reaction was then initiated by addition of a “master mix” containing all remaining reagents. This produced a reaction containing 100 mM MOPS pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 3 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 500 μM NADH, 10 U/mL adenylate kinase (myokinase), pyruvate kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, and IucA and substrates at varying concentrations as required for the particular assay. IucA concentration was generally 1–3 μM, however for several more compromised mutants (T284V, R288A, H425A, N428L, N551A, E552A, and N553A), the enzyme concentration was raised to 10–30 μM to provide reproducible activity. Trays containing reaction components were incubated for two minutes at 37 °C before addition of master mix to initiate the reaction. Pseudo-first order reactions were done at 37°C in triplicate in 96-well black polystyrene plates with clear bottoms (Costar). The absorbance at 340 nm was determined by a Biotek Synergy 4 plate reader. Absorbance values were converted to concentration (μM), and specific activity (nmol min−1 mg−1), and plotted versus time (min−1). The initial velocity plots were made in GraphPad Prism 6. Apparent kinetic constants for citrate were determined with 2 mM ATP and 100 mM hydroxylamine. Apparent kinetic constants for ATP used 2 mM citrate and 100 mM hydroxylamine. Finally, apparent kinetic constants for ahLys used 2mM each of citrate and ATP. Varied substrates were used at 7 concentrations bracketing a preliminary KM value, unless substrate inhibition or availability limited the high concentrations. For some mutant enzymes, KM values are unreliable where saturating substrate concentrations could not be met.

The NADH consumption assay for YP IucA was based on the same protocol as described above. The exception, however, was that the reaction was initiated when 80 μL master mix combined with 10 μL Yp IucA and 10 μL nucleophile. The surrogate nucleophile, hydroxylamine, was 100 mM when citrate and ATP were assayed. Initial velocity plots were fit with nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism 6 to either the Michaelis-Menten equation (1) or substrate inhibition (2) to obtain apparent kcat and KM values.

| Equation (1) |

| Equation (2) |

The order of addition experiments were performed in triplicate. Each well was set up with 10 μL of 25–40 μM hvKP IucA and 10 μL of 10x stock of varied substrate on opposing sides of the well. To initiate the reaction, master mix including the two substrates in fixed ratio was added to the well to a final volume of 100 μL that contained 2.5–4.0 μM hvKP IucA, 50 mM MOPS pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 3 mM PEP, 500 μM NADH, 10 U/mL myokinase, and 10 U/mL pyruvate kinase/lactic dehydrogenase. The path length corrected, blank subtracted, and stoichiometric corrected values were used plot the initial rates. The maximal slopes of initial rates and varied substrate concentration were reciprocally plotted and linearly fit in GraphPad Prism 6. Error bars in the double reciprocal plots are from the standard deviation of triplicate values, and some values at higher concentrations of varied citrate were omitted due their increased values near the Y-axis, stemming from partial substrate inhibition as described below.

Results

Examination of the kinetic mechanism of IucA.

Previously, we reported the steady state kinetic parameters of hvKP IucA for citrate, ATP, hydroxylamine, and N6-acetyl-L-lysine (aLys) (19). Synthesis of the physiological substrate ahLys (13) gave us the opportunity to evaluate the steady state characteristics of IucA with the natural substrate. We repeated the determinations from the prior study, providing values within 2–3 fold of prior apparent kinetic constants (Table 1). The KM of IucA with ahLys was 0.79 ± 0.02 mM, the kcat was 51.2 ± 0.5 min−1, and kcat/KM was 1,100 M−1s−1. We also tested the ability of analogs to substitute for citrate. Tricarballylic acid, lacking the tertiary hydroxyl, showed a 4-fold decrease in the apparent second order rate constant kcat/KM (Table 1). In contrast, no activity was detected with glutarate, 3,3-dimethylglutarate, α-ketoglutarate, or 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate (not shown). These results suggest that whereas the hydroxyl of citrate is partly expendable, the tertiary carboxylate appears more important.

Table 1.

Apparent kinetic constants for hvKP IucA and YP IucA

| Enzyme | Substrate | kcat (s−1) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hvKP IucA | ATPa | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 3.33 × 103 |

| ATP | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 6.64 × 103 | |

| Citratea | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 1.94 × 103 | |

| Citrate | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 1.29 × 103 | |

| Tricarballylic acid | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 2.20 ± 0.22 | 3.55 × 102 | |

| ahLys | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 1.08 × 103 | |

| Yp IucA | ATP | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 9.25 × 102 |

| Citrate | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 4.56 × 102 | |

| ahLysb | 0.83 ± 0.20 | 1.40 ± 0.50 | 5.95 × 102 |

Values from Bailey et al. (19).

YP IucA showed substrate inhibition with ahLys as the varying substrate resulting in a Ki=1.1 mM.

We additionally investigated whether IucA in the aerobactin-producing iucABCD operon from different bacteria retained similar activity. IucA from the Gram-negative opportunistic human pathogen, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (Yp IucA), was recombinantly expressed and purified. Yp IucA has 63% sequence identity with hvKP IucA, and similarly elutes as a tetramer as determined by size exclusion chromatography. Apparent kinetic constants for Yp IucA were similar to the IucA from hvKP, showing overall slightly lower catalytic efficiency, perhaps related to the poorer solubility of this protein (Table 1). Additionally, the pattern for ahLys kinetics illustrated substrate inhibition, which we have not observed previously with hvKP IucA. All remaining experiments were performed with the IucA protein from hvKP; we therefore drop the species designation below.

To characterize the kinetic mechanism of IucA, we performed a series of experiments designed to study the order of addition of substrates in the Iuc-catalyzed reaction. We examined whether the kinetic mechanism is sequential or is ping-pong, as seen with the adenylate forming enzymes of the ANL superfamily such as the acyl- and aryl-CoA synthetases that includes the Acyl-CoA synthetases, NRPS adenylation domains, and beetle Luciferase (26). To our knowledge, the kinetic mechanism of NIS synthetases have not been explored previously.

The possible mechanisms of terreactant enzymes can be distinguished graphically based on initial velocity plots (35, 36). In this method, two of the three substrates are maintained in a constant ratio to each other in the range of their Michaelis constant and the third substrate is varied. The initial velocity double reciprocal plot, as well as slope and Y-intercept replot patterns, distinguish between a sequential or ping-pong reaction (Table S3). The double reciprocal plots can be examined for parallel lines that would be indicative of a ping-pong mechanism, or intersecting lines for a sequential mechanism. The two different plot patterns result from the presence of a constant term in the denominator of the initial velocity rate equation of the sequential mechanism (37). Our goal was to identify which mechanisms, among 10 possibilities that have been described (35), could be eliminated on the basis of observed data.

Three sets of reciprocal plots, varying each substrate at fixed ratios of the remaining two, were analyzed for mechanistic insight (Figure 2). We first varied citrate at fixed ratios of ATP and ahLys, which were maintained in a ratio of 0.13, estimating the KM of 100 μM for ATP and 750 μM for ahLys. At concentrations lower than 0.5 KM for ATP and ahLys, we observed an intersecting pattern for the reciprocal plot of citrate (Figure 2A). We note that at concentrations of ATP and ahLys greater than their KM, the reciprocal plots of rate versus substrate citrate have parallel lines (data not shown) likely due to IucA having a KD smaller than its KM for variable substrate citrate (35). The next set of data utilized citrate and ahLys in a fixed ratio of 0.2 and varied ATP. This resulted in a double reciprocal plot in which the slopes of the citrate and ahLys ratios begin increasing after 0.5 KM, indicative of substrate inhibition. Therefore, more values of citrate and ahLys were evaluated below 0.5 KM (Figure 2B). Finally, citrate and ATP were maintained in a fixed ratio of 1.5, based on their KM, and ahLys was varied (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Kinetic analysis of the terreactant mechanism. Initial velocity measurements were collected with two substrates in a fixed ratio about their KM, while varying the third substrate. The double reciprocal plots are shown for (A) varying citrate at multiple concentrations of ATP and ahLys, which were at a fixed constant ratio, (B) ATP varied while citrate and ahLys were maintained in constant ratio, and (C) ahLys varied while citrate and ATP were kept at fixed rations around their KM values.

The three sets of initial rate plots are all intersecting, clearly ruling out the five ping-pong reaction mechanisms of Table S3. Additionally, because none of the plots shows intersecting lines on the 1/v axis, as would be required for substrate C of the partially random AB (mechanism 4), we could eliminate this possibility as well.

The shape of the slope and intercept replots from Figure 2 can then be used to determine among the remaining four mechanisms: 1. random, 2. ordered, 3. partially random AC (ordered B), and 5. partially random BC (ordered A). While the linearity and the intercept points are definitive (Table S3), in practice it can be difficult to distinguish linear and nonlinear, or the precise 1/v intercept when errors are taken into account (35). We therefore took a conservative approach to distinguish among the remaining mechanisms.

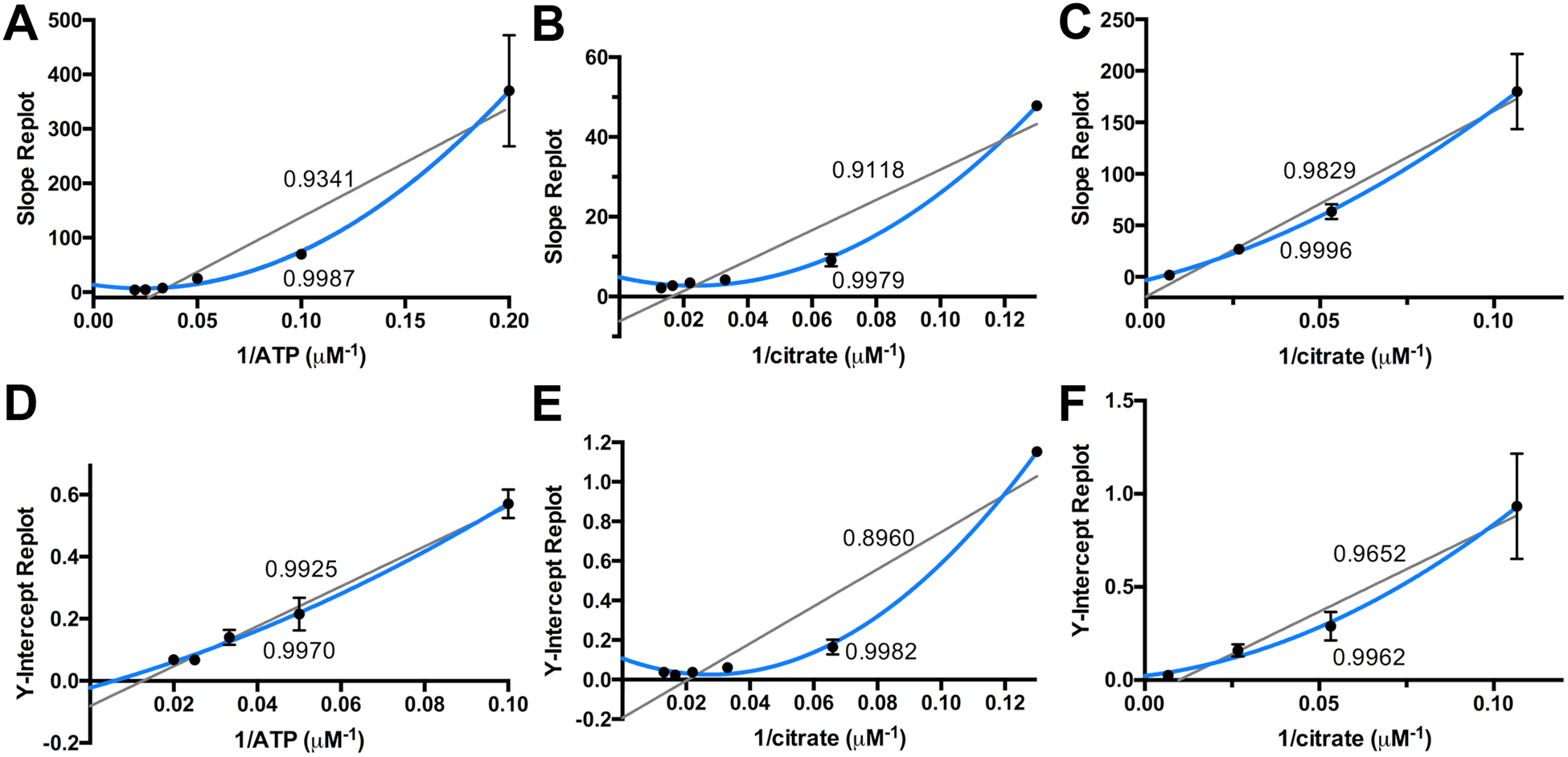

All of the replots show better fits to nonlinear (Figure 3). However, some, in particular the intercept replot of the varied citrate plot (Figure 3D), shows only a slight deviation from linear. The replots of the varied ATP rate plot slope and intercept clearly show nonlinear fits (Figures 3B and 3E), with non-zero intercepts. Examining the four remaining mechanisms, in considering ATP to be any of the three substrates, we can eliminate mechanism 5, leaving only the first three mechanisms to be considered.

Figure 3.

The slope and Y-intercept replots of Figure 2, fit linearly or parabolic. The R2 values for the linear fits are listed above the gray line, and the parabolic R2 values are listed below the blue line. The replots of A and D correspond to varying citrate, Figure 2A, the replots of B and E correspond to varying ATP, Figure 2B, and replots C and F correspond to varying ahLys, Figure 2C. The 0.2 μM−1 1/ATP data point of D has been omitted due to high error.

Another method to differentiate between the remaining mechanisms is to saturate one of the substrates and vary another, at constant levels of the third substrate near its KM (35). Double reciprocal plot analysis of the saturating substrate method can be associated with the same table of mechanisms as in the first portion of analysis. The initial velocity outcomes for the remaining mechanisms are presented in Table S4. The saturating, 50 × KM parameter was investigated for citrate and ATP, but not ahLys due to its limited availability. Saturating citrate conditions produced more observations of substrate inhibition, to the extent that the resultant plots were not usable. Saturating ATP in Figure 4A and 4B display an intersecting pattern, with neither intercept on the 1/v axis. This eliminates mechanism 3 from consideration regardless of whether ATP is substrate A, B, or C.

Figure 4.

Saturating ATP (5 mM, ~50 × KM) with varied with (A) citrate or (B) ahLys. Saturating ahLys was not used due to its limited availability.

We are left then to consider the first two mechanisms with a completed random sequential binding or an ordered mechanism. Examining the slope and intercept replots of Table S3, the only difference for these two mechanisms would be the linear fit to the intercept of the second substrate to add. As noted above, among all of the replots of Figure 3, the intercept replot for variable citrate does indeed appear to be linear. This raises the possibility of an ordered reaction with citrate adding second.

Thermal shift stability assay of IucA with substrates and substrate analogs.

We therefore sought a second biophysical technique to assess substrate binding to IucA. We used the thermal shift stability assay to assess if ligands could bind to and stabilize IucA (32, 33). Further, we examined whether combinations of different ligands could serve to support the kinetic analysis of the order of addition. IucA was combined with an excess of the three substrates independently (Figure 5). Additionally, four ATP analogs were used, AMPCPP, AMPPCP, AMPPNP, and ATPγS. Three nucleotides ATP, AMPCPP, and ATPγS, all resulted in an increase in protein stability with a shift in melting temperature of > 2.5 °C. The other nucleotides, AMPPCP and AMPPNP, had no change on stability, likely reflecting the importance of the γ-phosphate or the β-γ bridging oxygen in proper binding of ATP. In contrast to the nucleotides, the addition of citrate and ahLys did not result in a stabilization of IucA with ahLys resulting in a slight decrease in the melting temperature. Further, the inclusion of ATP and citrate resulted in another 2 °C upward shift in the melting temperature compared to nucleotide alone.

Figure 5. Thermal Shift Stabilization by IucA Ligands.

The melting temperature as reflected in the thermal shift assay is shown for IucA bound to substrates or nucleotide analogs. Data are shown as mean with error bars representing standard deviation (n=3).

Combined, the ability of ATP but not citrate to stabilize IucA and the linear replot of the citrate intercepts (Figure 3D) lead to the proposal that the IucA reaction mechanism is an ordered mechanism with ATP, citrate, and ahLys binding sequentially to the enzyme. This conclusion is also consistent with the structure of the enzyme active site, with ATP being more deeply buried in the enzyme (19) and an open pocket above where citrate and ahLys could bind.

IucA Citrate and ATP Mutants.

Next we used mutagenesis and biochemical assays to explore the roles of specific residues in the IucA reaction. To inform our understanding of the active site, the structure of IucA bound to ATP (PDB ID 5JM8) (19) was compared to the structure of AcsD bound to ATP and N-citryl-ethylenediamine (PDB ID 2X3J) (23). These structures (Figure 6A) helped identify a number of residues that we targeted with mutagenesis and kinetic analysis (Table 2).

Figure 6. Structure of IucA active site.

(A) Stereorepresentation of the active site of IucA bound to ATP A. The IucA structure (5JM8) highlights several residues involved in interactions with ATP. (B) The IucA structure (white) is superimposed on the structure of AcsD (pink, 2X3J) bound to ATP and citryldiaminoethane (Cit-DEA). Residues used in mutagenesis studies are shown. (C) Surface representation of IucA bound to ATP. The active site cavity includes ATP. The disordered 550 loop is depicted by a yellow (panels A and B) or red (panel C) dashed line.

Table 2.

Apparent kinetic constants for wild-type and mutant enzymes.

| Protein | Substrate | kcat (s−1) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) | kcat/KM HAa (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTb | Citrate | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 1.94 × 103 | |

| WT | Citrate | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 1.29 × 103 | |

| H147F | Citrate | (1.3 ± 0.1) × 10−2 | 10.1 ± 1.3 | 1.32 | |

| T284V | Citrate | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 10−4 | 5.72 ± 1.47 | 2.02 × 10−2 | |

| R288K | Citrate | (2.2 ± 0.1) × 10−2 | 3.76 ± 0.71 | 5.90 | |

| R288A | Citrate | (7.53 ± 0.27) × 10−4 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | 1.86 | |

| H425A | Citrate | (1.48 ± 0.09) × 10−3 | 15.7 ± 1.8 | 9.41 × 10−2 | |

| H425N | Citrate | (7.67 ± 0.10) × 10−2 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 8.63 × 101 | |

| N542L | Citrate | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 0.71 ± 0.18 | 1.12 × 103 | |

| WTb | ATP | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 3.33 × 103 | |

| WT | ATP | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 6.64 × 103 | |

| M274W | ATP | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 4.36 × 103 | |

| H425N | ATP | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 6.77 × 102 | |

| N428L | ATP | (3.90 ± 0.06) × 10−3 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 2.28 × 101 | |

| WT | ahLys | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 1.08 × 103 | 21 |

| R297A | ahLys | 2.83 ± 0.30 | 3.18 ± 0.63 | 8.91 × 102 | |

| L423E | ahLys | (6.00 ± 0.15) × 10−2 | 2.74 ± 1.36 | 2.19 × 101 | 142 |

| Q447A | ahLys | 1.29 ± 0.30 | 3.64 ± 1.66 | 3.55 × 102 | 19 |

| F471Y | ahLys | 1.68 ± 0.34 | 1.58 ± 0.73 | 1.06 × 103 | |

| Y479A | ahLys | 4.93 ± 1.91 | > 20 | < 200 | |

| Y479R | ahLys | 0.46 ± 0.11 | 5.77 ± 2.01 | 7.94 × 101 | 38 |

| Y483A | ahLys | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 5.12 ± 2.18 | 3.58 × 101 | |

| Y483F | ahLys | 1.70 ± 0.65 | 16.5 ± 7.9 | 1.03 × 102 | |

| Y483C | ahLys | (7.50 ± 1.67) × 10−2 | 3.54 ± 1.38 | 2.12 × 101 | 24 |

| N551Ac | ahLys | -- | 23 | ||

| E552A | ahLys | (1.21 ± 0.10) × 10−3 | > 50 | < 2 | 4 |

| N553Ac | ahLys | -- | 22 |

Apparent kinetic constants with surrogate nucleophile were determined for mutant enzymes with large effect on ahLys; for residues with multiple designed mutations, only a single mutant was tested.

Values from Bailey et al. (19).

No activity was detected for N551A and N553A with 30 μM enzyme concentration.

To assess the overall stability of IucA mutants, we used a fluorescence based thermal shift assay. The thermal stability measurements indicated that all mutants were similar to wild-type, with the exception of the M274W mutant, which showed a melting temperature reduced by ~5 °C, perhaps indicating a significant decrease in protein stability (Figure S1). Additionally, for enzymes harboring mutations in the potential nucleophile binding pocket, we assessed activity with hydroxylamine, confirming the ability of the enzymes to catalyze the initial partial reaction (see below).

We first tested the role of residues that interact with citrate in AcsD and are similarly positioned in IucA. His147 is proposed to interact with the non-reacting primary carboxylate, while Thr284 is predicted to hydrogen bond with the tertiary carboxylate. Mutation of either residue compromised activity with greater than 10-fold effect on KM and an even larger effect on kcat. In contrast, mutating Asn542, which is located near the nonreacting primary carboxylate, had no effect on the activity. Mutation of either Arg288 or His425, which are both predicted to interact with the reacting carboxylate of citrate, also had a very large effect on the catalysis. Removal of the side chain in the R288A and H425A mutants had a dramatic effect on the kcat, while more conservative changes in R288K and H425N were less detrimental. Because the H425N mutant retained some activity and could still be saturated with citrate, we also calculated the apparent kinetic constants with ATP. Positioned near the α-phosphate of ATP, this mutation resulted again in a 10-fold decrease in apparent kcat or kcat/KM for ATP.

The crystal structures of both IucA and AcsD contain a cavity near the γ-phosphate of ATP that may accept the pyrophosphate byproduct of the first partial reaction (18). To investigate the role of this pocket, we mutated Met274, a residue prominently bordering this chamber, to a tryptophan in an attempt to introduce additional steric bulk into this region, potentially impacting activity. The M274W enzyme was fully competent to catalyze the reaction. Potentially, other larger substitutions to residues that border this cavity could influence activity. Finally, Gln427, Asn428, and Asp445 are structurally positioned to interact with the Mg2+ ion, coordinating the ATP through the α,β-bridging oxygen and oxygens on the α- and γ-phosphates. Disrupting Mg2+ coordination in a N428A mutant resulted in a greater than 100-fold decrease on kcat and kcat/KM.

IucA Nucleophile Binding Site Mutants.

Limited structural information exists concerning the positioning of the diverse substrates within the nucleophile binding pocket for NIS synthetases. The structure of the AcsD binding pocket with the diamine moiety of N-citryl-ethylenediamine provides the most compelling evidence (23); however, we note that serine, the natural nucleophile of AcsD, and the corresponding ethylenediamine moiety of the bound product analog, are both significantly smaller than ahLys, the nucleophile for the IucA reaction. We therefore used site-directed mutagenesis to explore a wide range of potential active site residues that may be relevant for binding ahLys.

We focused our attention on residues that were conserved in other IucA homologs and that were directed into the potential nucleophile binding pocket. In particular, we mutated Arg297, Leu423, Gln447, Phe471, Tyr479, and Tyr483 (Figure 6B). Additionally, we noticed that a disordered loop near the active site spanning Asp549 to Pro558 contained a Asn-Glu-Asn tripeptide centered on Glu552 (Figure 6C) that was conserved in nearly all IucA sequences (Figure S2), although not in other NIS synthetases.

The R297A and F471Y mutations showed no effect. These residues are both >10 Å from the reacting carboxylate of the citrate moiety and perhaps define the extent of the ahLys binding pocket. Similarly, a Q447A mutation showed only minimal effect on activity, suggesting that Gln447, which is only 8Å from the citrate carboxylate, also does not contribute to the proper positioning of the ahLys nucleophile.

In contrast, the remaining mutations had much more dramatic effects on IucA activity. We replaced Leu423 with a glutamate. AcsD contains a glutamate at the homologous position that projects toward the diamine moiety of the product. The L423E mutant of IucA is severely compromised for the reaction with ahLys. Mutation of the tyrosine residues at positions 479 and 483 also showed dramatic effects on the catalytic reaction with ahLys. Finally, mutation of the three residues of the Asn-Glu-Asn motif showed some of the largest effects on activity for the ahLys binding pocket results. This suggests that these residues on this flexible loop may contribute to the active site. Interestingly, the N551A and N553A mutations showed no detectable activity even at elevated enzyme concentration. Further, we note that the activity with the surrogate nucleophile hydroxylamine was only marginally impacted with all mutant enzymes tested, suggesting the enzymes were properly folded and competent to carry out the initial adenylation reaction.

Discussion

Herein, we explored the biochemistry of IucA, a NIS synthetase that is responsible for installing the first ahLys group onto the primary carboxylate of citrate to form the chiral intermediate 3S-citryl-2’S-ahLys. We have demonstrated a sequential terreactant catalytic mechanism in which all three substrates bind prior to reaction and release of any of the three products. Our data are most consistent with an ordered mechanism with the three substrates binding in the order of ATP, citrate, and then ahLys. These data are supported by the kinetic analysis presented here, our binding data, as well as a view of the enzyme active site. We have confirmed the importance of several residues that were implicated from structural studies in the binding of the different substrates and, lacking experimental structural evidence for the binding of the nucleophile ahLys, we have probed residues that surround the likely nucleophile cavity to implicate several residues, including a unresolved loop that likely closes over the substrates after they are all bound.

The Adenylation Catalytic Site.

We present here detailed functional analysis of the role of residues that bind to ATP and citrate within the active site. While several residues that we targeted showed no effect on activity, most were significantly impacted. The study of AcsD similarly examined several of these residues (18). In particular, Arg305 and His444 of AcsD, which are homologous to Arg288 and His425 of IucA, both showed 1% of the specific activity of the wild-type AcsD protein. We show herein a dramatic effect on kcat for alanine substitutions of either residue, which could be partly restored by providing a similar side chain group in the R288K and H425N mutants. The side chain of His147 stacks upon the adenine base of ATP and also interacts with the non-reacting primary carboxylate of citrate. The substitution of this side chain with a phenylalanine, which should maintain the ability to stack with the nucleotide, resulted in a loss in kcat/KM for citrate by three orders of magnitude. This suggests that the histidine plays a role in positioning the citrate through the distal carboxylate. In AcsD, Thr301, which is the structural homolog of Thr284 in IucA, is seen to interact with the tertiary carboxylate of citrate. The substitution of this residue with a valine is the most severely compromised mutant that we analyzed. The importance of this binding interaction with the tertiary carboxylate is consistent with the observation that IucA was able to utilize tricarballylic acid, a citrate analog lacking the central hydroxyl group, but not glutarate or 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate. Furthermore, the presumed interaction of Thr284 with the tertiary carboxylate also plays a role in directing the orientation of the prochiral citrate molecule, thereby directing the stereochemistry of the citryl group in the IucA-catalyzed reaction.

The nucleophile binding pocket.

Type A NIS synthetases should share similar active sites for the initial reaction to adenylate the citrate substrate. In contrast, the nucleophile used in the second partial reaction differs among distinct homologs. Pioneering studies by Challis and colleagues explored the substrate specificity and binding residues in AcsD (18, 23). A fairly broad range of substrates could serve as a nucleophile in place of the physiological substrate serine. The influence of Glu442, Arg501, and Lys563 on nucleophile specificity were all tested with various mutations and potential substrates. A K563A mutant of AcsD was poorly expressed. Changes to AcsD Glu442, which is located at a position equivalent to Leu423 in IucA, blocked activity with all substrates. Finally, the Arg501 position of AcsD could be substituted with lysine, maintaining some activity with serine, ethylenediamine, or 1,2-diaminopropane. Arg501 is equivalent to Tyr479 in IucA and inspired several of the substitutions that we made. While some mutant enzymes that we produced had weak activity with the AcsD substrate serine, most did not and none showed a significant improvement with the non-canonical substrate compared to wild-type IucA.

Lacking structural information to defining the binding interactions for ahLys in IucA, we explored potential residues through site-directed mutagenesis. Our results suggest that Leu423, Tyr479, and Tyr483 interact with ahLys to properly position the nucleophile for the second partial reaction. In contrast, the other wall of the pocket formed by Arg297 and Phe471 appears not to contribute to nucleophile binding.

We also note that our structures of IucA in the absence or presence of ATP (19) both showed a large disordered loop (designated the 550 loop) from residues Asp549 to Pro558. An analogous loop is also disordered in the structures of IucC (13), AcsD (18), AlcC (20), and DfoC (22), but not in AsbB (21). Examination of IucA sequences from multiple Gram-negative species illustrates that, within this loop, an Asn-Glu-Asn motif is highly conserved (Figure S2). Previously, to structurally characterize the type C IucC from the aerobactin biosynthesis pathway, we improved crystallization by the use of surface entropy reduction (13). We generated 12 enzyme variants with changes at surface residues. Indeed, our final structure of IucC used a mutant designated M5, which contained five substitutions between residues 181 and 188; in this structure, the active site 550 loop was also disordered. A second mutant enzyme, designated M12, contained 7 substitutions designed within an 8-residue span of the 550 loop. Although designed for use in structural studies, we tested the function of this enzyme and showed that it contained no IucC activity (13), supporting the importance of this active site loop in other NIS synthetases.

In IucA, the two asparagine mutations, N551A and N553A, showed no detectable activity with ahLys, yet remained functional with the non-specific surrogate nucleophile hydroxylamine. Further, wild-type IucA has an apparent kcat/KM for N6-acetyllysine that is approximately 100-fold lower than ahLys (19). We could detect activity of the two asparagine mutants with N6-acetyllysine (Table S1) at levels similar to wild-type. This suggests that regions of this loop may interact with the hydroxamate moiety of the physiological nucleophile. Although distal to the reacting portion of the nucleophile, a selectivity filter that ensures the proper substrate (ahLys ≫ Lys or acetyllysine) is not surprising given the higher relative concentration of lysine within the cell.

Combined, our study of IucA presents a new view of the reaction catalyzed by IucA, a prototypical NIS synthetase. All three substrates must bind in the enzyme active site prior to reaction. Potentially, the lid loop may partly or completely close over the active site with some residues directly engaging the nucleophile. Once all three substrates are present, the initial adenylation reaction is initiated, followed by attack of the α-amino group of ahLys on the adenylate to form citryl-ahLys and AMP. A large binding pocket with room for all three substrates ensures the proper positioning of the substrates for both steps in the complete reaction.

A more complicated situation exists in some Type C enzymes that use carboxylate substrates other than citrate. The Type C enzymes involved in the production of hydroxamate siderophores such as desferrioxamine, bisucaberin, avaroferrin, and putrebactin catalyze the polymerization of two or three intermediates to form linear or cyclic dimers and trimers of the component building blocks (14, 38). Elegant studies by Rütschlin and Böttcher (24) have shown that the NIS enzymes AvbD and DesD produce macrocyclic siderophores from multiple copies of an N-hydroxy-N-succinylcadaverine or N-hydroxy-N-succinylputrescine, building blocks that contain both the carboxylate and the nucleophilic amine within the same molecule. Each cycle of the adenylation and amide-forming reaction may then catalyze the multimerization from two building blocks, may extend a dimer to form a trimeric species, or, when the proper length is reached, catalyze the macrocyclization to the cyclic dimer or trimer. Each step in the extension or cyclization will require activation of the carboxylate through adenylation, followed by nucleophile displacement of the AMP to complete the extension or macrocyclization. These studies emphasize that a single Type C enzyme will be able to adenylate substrates of varying lengths and catalyze the second partial reaction with either a second nucleophile substrate or catalyze the macrocyclization by directing the distal amine of the linear dimer or trimer back towards the carbonyl of the adenylate intermediate.

It is reasonable to assume that ATP binds in the same position regardless of the substrates being ligated together. However, there remain several interesting questions. First, how do these Type C enzymes accommodate diverse substrates for both steps in the reaction? Second, in the production of trimeric products, how does a dimeric intermediate from the first extension reaction migrate to the nucleophile site for the subsequent reaction, along with concomitant release of AMP and pyrophosphate and rebinding of ATP? And finally, how do the enzymes modulate extension and cyclization of dimeric and trimeric substrates? We propose that the flexible loops of the NIS synthetase may serve to capture the substrates and that differences within the 550 loop and others may help to direct the specific reaction.

Conclusions

To continue our studies of the enzymes involved in the production of aerobactin, we present here a mechanistic investigation of the IucA, the NRPS-independent siderophore synthetase. Like other members of this enzyme family, IucA catalyzes a two-step reaction to first adenylate a carboxylate substrate at the expense of a molecule of ATP, followed by formation of an amide in a second partial reaction. We present a detailed kinetic analysis that shows that the mechanism involves the formation of a quaternary complex with all three substrates. Our data are most consistent with an ordered reaction mechanism in which ATP binds first, followed by citrate and the nucleophile ahLys. While we do not yet have structural data to characterize the binding pocket for ahLys, our data point to the involvement of several important residues, including three residues that exist on a dynamic loop near the C-terminus of the protein. A more complete understanding of the structural and mechanistic features of IucA and of the enzymes in aerobactin biosynthesis may lead to the development of small molecule probes to block production of this important virulence factor in K. pneumoniae.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Prof. Courtney C. Aldrich and Evan Alexander for the generous gift of synthetic ahLys that was used in biochemical assays. This work was supported with funding from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease, NIH (AI-116998).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Supporting Information.

The Supporting information associated with this manuscript is available free of charge on the ACS website:

The catalytic efficiency of mutations on the 550 loop (Table S1), Mutagenesis primers (Table S2), Graphical Analysis of kinetic data (Table S3), Saturating Substrate graphical analysis (Table S4), Thermal shift data for wt and mutant enzymes (Figure S1), and Sequence alignment of IucA homologs (Figure S2).

REFERENCES

- 1.Marr CM, and Russo TA (2019) Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae: A New Public Health Threat, Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 17, 71–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo TA, and Gulick AM (2019) Aerobactin Synthesis Proteins as Antivirulence Targets in Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae, ACS Infect Dis 5, 1052–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sellick JA, and Russo TA (2018) Getting Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae on the Radar Screen, Curr Opin Infect Dis 31, 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll CS, and Moore MM (2018) Ironing out Siderophore Biosynthesis: A Review of Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase (Nrps)-Independent Siderophore Synthetases, Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 53, 356–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamb AL (2015) Breaking a Pathogen’s Iron Will: Inhibiting Siderophore Production as an Antimicrobial Strategy, Biochim Biophys Acta 1854, 1054–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nassif X, and Sansonetti PJ (1986) Correlation of the Virulence of Klebsiella Pneumoniae K1 and K2 with the Presence of a Plasmid Encoding Aerobactin, Infect Immun 54, 603–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo TA, Olson R, MacDonald U, Beanan J, and Davidson BA (2015) Aerobactin, but Not Yersiniabactin, Salmochelin and Enterobactin, Enables the Growth/Survival of Hypervirulent (Hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella Pneumoniae Ex Vivo and in Vivo, Infect Immun 83, 3325–3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo TA, Olson R, MacDonald U, Metzger D, Maltese LM, Drake EJ, and Gulick AM (2014) Aerobactin Mediates Virulence and Accounts for the Increased Siderophore Production under Iron Limiting Conditions by Hypervirulent (Hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella Pneumoniae, Infect Immun 82, 2356–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbonetti NH, and Williams PH (1984) A Cluster of Five Genes Specifying the Aerobactin Iron Uptake System of Plasmid Colv-K30, Infect Immun 46, 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lorenzo V, Bindereif A, Paw BH, and Neilands JB (1986) Aerobactin Biosynthesis and Transport Genes of Plasmid Colv-K30 in Escherichia Coli K-12, J Bacteriol 165, 570–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford S, Cooper RA, and Williams PH (1986) Biochemical Genetics of Aerobactin Biosynthesis in Escherichia-Coli, Fems Microbiology Letters 36, 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neilands JB (1992) Mechanism and Regulation of Synthesis of Aerobactin in Escherichia Coli K12 (Pcolv-K30), Can J Microbiol 38, 728–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey DC, Alexander E, Rice MR, Drake EJ, Mydy LS, Aldrich CC, and Gulick AM (2018) Structural and Functional Delineation of Aerobactin Biosynthesis in Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae, J Biol Chem 293, 7841–7852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Codd R, Soe CZ, Pakchung AAH, Sresutharsan A, Brown CJM, and Tieu W (2018) The Chemical Biology and Coordination Chemistry of Putrebactin, Avaroferrin, Bisucaberin, and Alcaligin, J Biol Inorg Chem 23, 969–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Challis GL (2005) A Widely Distributed Bacterial Pathway for Siderophore Biosynthesis Independent of Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases, Chembiochem 6, 601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kadi N, Oves-Costales D, Barona-Gomez F, and Challis GL (2007) A New Family of Atp-Dependent Oligomerization-Macrocyclization Biocatalysts, Nat Chem Biol 3, 652–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oves-Costales D, Kadi N, and Challis GL (2009) The Long-Overlooked Enzymology of a Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase-Independent Pathway for Virulence-Conferring Siderophore Biosynthesis, Chem Commun (Camb), 6530–6541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmelz S, Kadi N, McMahan SA, Song L, Oves-Costales D, Oke M, Liu H, Johnson KA, Carter L, Botting CH, White MF, Challis GL, and Naismith JH (2009) Structure and Function of Acsd a New Class of Adenylating Enzyme That Catalyzes Enantioselective Citrate Desymmetrization in Pathogenicity-Conferring Siderophore Biosynthesis, Nat Chem Bio 5, 174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey DC, Drake EJ, Grant TD, and Gulick AM (2016) Structural and Functional Characterization of Aerobactin Synthetase Iuca from a Hypervirulent Pathotype of Klebsiella Pneumoniae, Biochemistry 55, 3559–3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oke M, Carter LG, Johnson KA, Liu H, McMahon SA, Yan X, Kerou M, Weikart ND, Kadi N, Sheikh MA, Schmelz S, Dorward M, Zawadzki M, Cozens C, Falconer H, Powers H, Overton IM, van Niekerk CA, Peng X, Patel P, Garrett RA, Prangishvili D, Botting CH, Coote PJ, Dryden DT, Barton GJ, Schwarz-Linek U, Challis GL, Taylor GL, White MF, and Naismith JH (2010) The Scottish Structural Proteomics Facility: Targets, Methods and Outputs, J Struct Funct Genomics 11, 167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nusca TD, Kim Y, Maltseva N, Lee JY, Eschenfeldt W, Stols L, Schofield MM, Scaglione JB, Dixon SD, Oves-Costales D, Challis GL, Hanna PC, Pfleger BF, Joachimiak A, and Sherman DH (2012) Functional and Structural Analysis of the Siderophore Synthetase Asbb through Reconstitution of the Petrobactin Biosynthetic Pathway from Bacillus Anthracis, J Biol Chem 287, 16058–16072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salomone-Stagni M, Bartho JD, Polsinelli I, Bellini D, Walsh MA, Demitri N, and Benini S (2018) A Complete Structural Characterization of the Desferrioxamine E Biosynthetic Pathway from the Fire Blight Pathogen Erwinia Amylovora, J Struct Biol 202, 236–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmelz S, Botting CH, Song L, Kadi NF, Challis GL, and Naismith JH (2011) Structural Basis for Acyl Acceptor Specificity in the Achromobactin Biosynthetic Enzyme Acsd, J Mol Biol 412, 495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rütschlin S, and Bötcher T (2018) Dissecting the Mechanism of Oligomerization and Macrocyclization Reactions of Nrps-Independent Siderophore Synthetases, Chemistry 24, 16044–16051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll CS, Grieve CL, Murugathasan I, Bennet AJ, Czekster CM, Liu H, Naismith J, and Moore MM (2017) The Rhizoferrin Biosynthetic Gene in the Fungal Pathogen Rhizopus Delemar Is a Novel Member of the Nis Gene Family, Int J Biochem Cell Biol 89, 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gulick AM (2009) Conformational Dynamics in the Acyl-Coa Synthetases, Adenylation Domains of Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases, and Firefly Luciferase, ACS Chem Biol 4, 811–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadi N, and Challis GL (2009) Chapter 17. Siderophore Biosynthesis a Substrate Specificity Assay for Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase-Independent Siderophore Synthetases Involving Trapping of Acyl-Adenylate Intermediates with Hydroxylamine, Methods Enzymol 458, 431–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert X, and Gouet P (2014) Deciphering Key Features in Protein Structures with the New Endscript Server, Nucleic Acids Res 42, W320–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeLano WL (2002) The Pymol Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrodinger LLC. (2019) The Pymol Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.3 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabsch W (1976) A Solution for the Best Rotation to Relate Two Sets of Vectors, Acta Crystallogr A 32, 922–923. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cummings MD, Farnum MA, and Nelen MI (2006) Universal Screening Methods and Applications of Thermofluor, J Biomol Screen 11, 854–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey DC, Buckley BP, Chernov MV, and Gulick AM (2018) Development of a High-Throughput Biochemical Assay to Screen for Inhibitors of Aerobactin Synthetase Iuca, SLAS Discov 23, 1070–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu MX, and Hill KA (1993) A Continuous Spectrophotometric Assay for the Aminoacylation of Transfer Rna by Alanyl-Transfer Rna Synthetase, Anal Biochem 211, 320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudolph FB, and Fromm HJ (1979) Plotting Methods for Analyzing Enzyme Rate Data, Methods Enzymol 63, 138–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segel IH (1975) Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-State Enzyme Systems, John Wiley & Sons, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cleland WW (1970) Steady State Kinetics, In The Enzymes, Volume Ii: Kinetics and Mechanism (Boyer PD, Ed.) 3rd ed., pp 1–65, Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rütschlin S, Gunesch S, and Böttcher T (2017) One Enzyme, Three Metabolites: Shewanella Algae Controls Siderophore Production Via the Cellular Substrate Pool, Cell Chem Biol 24, 598–604 e510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.