Abstract

This cohort study assesses the racial differences in rates of autopsy in groups of decedents older than 18 years from 2008 to 2017 in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research database.

In contrast to forensic autopsies mandated by law, clinical autopsies are performed to clarify diagnoses. Rates of clinical autopsies have declined, from a high of 19% (1950s-1970s) to 8% (2007).1 This decrease is related to financial, legal, and administrative disincentives, as well as perceptions that diagnostic improvements render autopsies obsolete.2 In the background of low enthusiasm from the health care system, patient/caregiver factors may be related to the rates of autopsies. Limited data suggest that white race is associated with lower autopsy rates.3 Using a cohort design, we explored the rates of autopsies for differences within racial groups.

Methods

We included decedents older than 18 years from 2008 to 2017 in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research database.4 We excluded deaths from external causes (homicides, suicides, and accidental deaths) and those with unknown autopsy status. Mortality and autopsy data were extracted from death certificates. Data were collected from November 1, 2019, to December 15, 2019, and analysis was completed on January 3, 2020. This research has been found to not require Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center institutional review board oversight consistent with its policy on publicly available deidentified data.

We compared the rates of autopsies by race for all deaths and deaths attributed to cancer, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, and respiratory disease using χ2 analysis. We tested the existence of linear trends of autopsy percentage. All tests were 2-tailed, and the α level of significance was set at .05. We performed statistical analyses using SPSS, version 21 (IBM Corp) and R, version 3.6.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

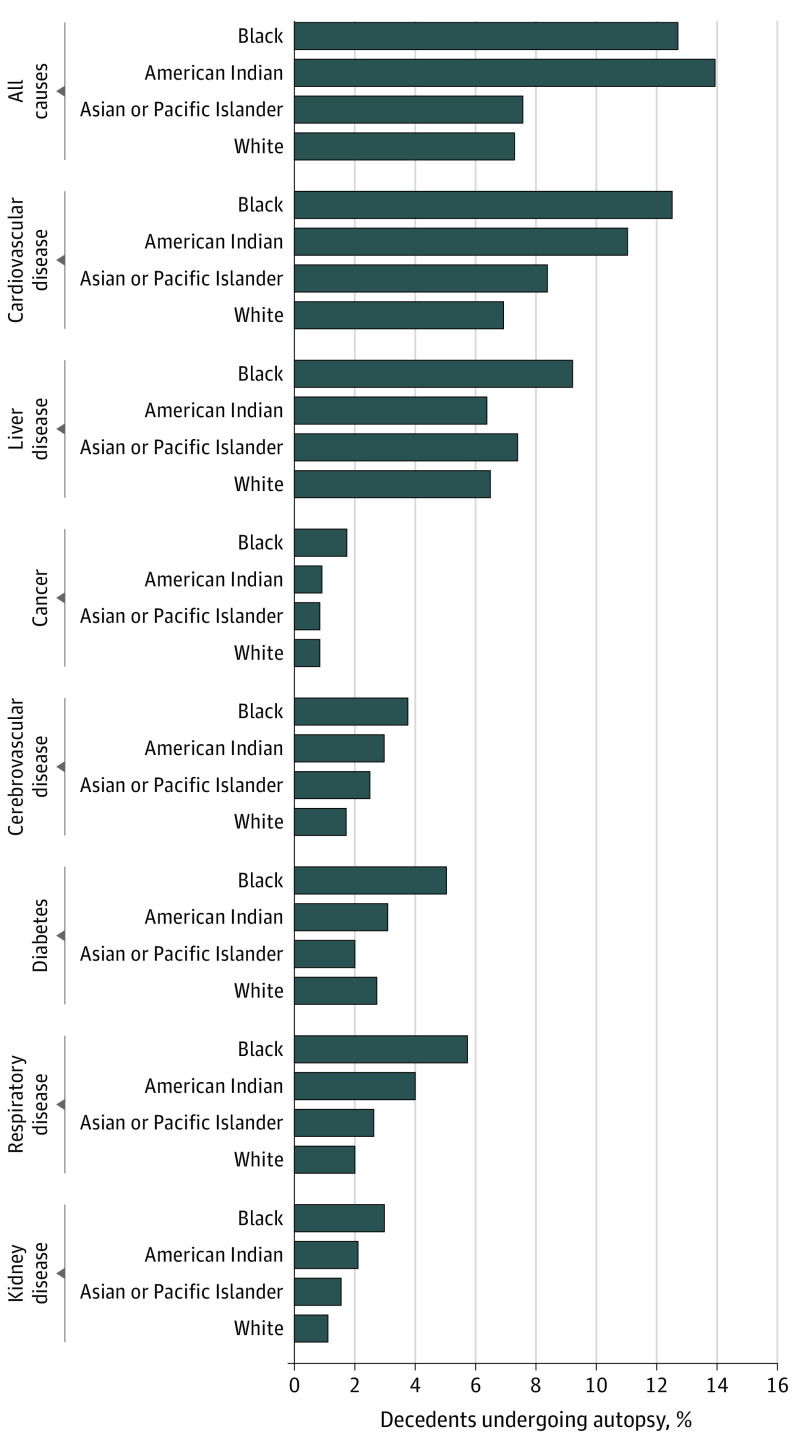

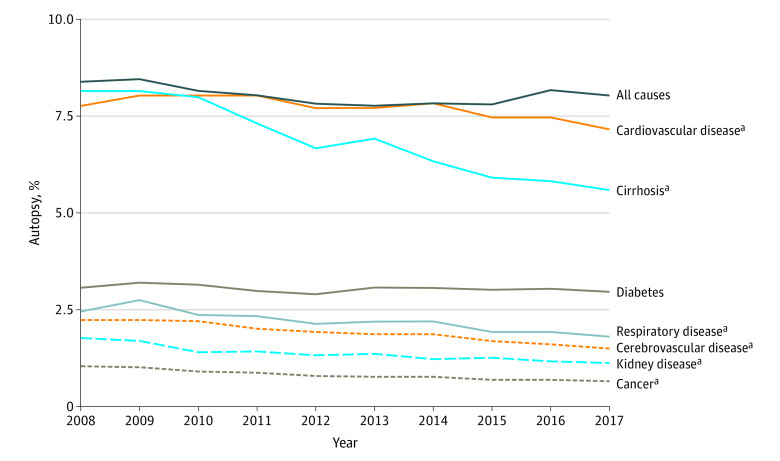

Of 25 543 152 total decedents, 1 873 146 individuals (7.3%) had unknown autopsy status and were excluded. Among 23 670 006 eligible decedents (73.9% aged >65 years, 49.6% women, and 85.7% white), the overall rate of autopsy was 7.9% and was higher in black individuals (12.7%; 95% CI, 12.7%-12.8%) compared with white individuals (7.3%; 95% CI, 7.3%-7.3%) (P < .01) (Figure 1). The difference in autopsy rates between black and white decedents was 5.4% (95% CI, 5.4%-5.5%). Rates of autopsy overall were higher in deaths attributed to cardiovascular disease (7.6%) and cirrhosis (6.7%), compared with cancer (0.9%) and kidney diseases (1.5%) (Figure 2). Across all conditions, black individuals had a significantly higher rate of autopsies compared with white individuals (difference between races: 0.9% in cancer and 5.6% in cardiovascular disease) (Figure 1). Except for diabetes-related death, rates of autopsies among deaths from other causes of death (eg, cancer and cirrhosis) declined over the study period (P < .01).

Figure 1. Racial Disparity in Autopsy Rates With Underlying Cause of Death, 2008-2017.

Figure 2. Annual Rates of Autopsy From 2008-2017, Overall and by Attributed Cause of Death.

aFor cardiovascular disease, P = .004 for trend. For all others, P < .001 for trend.

Discussion

Among nonforensic deaths from 2008 to 2017, the rates of autopsies were higher in black than in white decedents, overall, and across multiple major causes of death. Consistent with data since the 1950s, rates of autopsies continued to decline.

These findings are important for 2 reasons. First, the costs of autopsies are not typically reimbursed and are estimated to be $1000 to $4000.1,5 This cost is absorbed by the institution or passed on to caregivers, exposing them to financial burden. Second, recent publications have recommended autopsies to enhance education, quality assessment, and outcomes research.2,6 We hypothesize that the higher rate of autopsies in black decedents may reflect health disparities. Less-aggressive diagnostic workups in black patients may translate into less-established diagnoses before death, possibly associated with the rates of autopsies. This higher rate of autopsies in black decedents could also reflect altruism, obtaining autopsies for the promotion of science. In addition, the higher rate may represent caregivers wanting to know the “real cause of death,” suggesting mistrust of the health care system.

This analysis has limitations. We could not determine whether an autopsy was offered or discussed. We were unable to determine the motivation for an autopsy—whether for a contribution to science, to determine cause of death, or a combination of these factors. Unlike an earlier analysis,3 we did not perform risk adjustment since unmasking the deidentified database may have occurred. In addition, we cannot exclude unmeasured confounding by incorrect attribution as a nonforensic death, and our exclusion criteria do not fully cover all causes legally requiring autopsy. Despite these limitations, these data suggest differences in rates of autopsies by race and deserve further study.

References

- 1.Hoyert DL. The changing profile of autopsied deaths in the United States, 1972-2007. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(67):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Cock KM, Zielinski-Gutiérrez E, Lucas SB. Learning from the dead. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(20):1889-1891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1909017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemetz PN, Leibson C, Naessens JM, Beard M, Tangalos E, Kurland LT. Determinants of the autopsy decision: a statistical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108(2):175-183. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/108.2.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC WONDER. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- 5.Nemetz PN, Tanglos E, Sands LP, Fisher WP Jr, Newman WP III, Burton EC. Attitudes toward the autopsy—an 8-state survey. MedGenMed. 2006;8(3):80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson TF, Salazar JW, Vittinghoff E, et al. Association of QT-prolonging medications with risk of autopsy-defined causes of sudden death. JAMA Intern Med. Published online March 2, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]