Abstract

Background

Anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) contribute significantly to disability adjusted life years in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs). Screening has been proposed to improve identification and management of these disorders, but little is known about the validity of screening tools for these disorders. We conducted a systematic review of validated screening tools for detecting anxiety and PTSD in LMICs.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health and PsychINFO were searched (inception-April 22, 2020). Eligible studies (1) screened for anxiety disorders and/or PTSD; (2) reported sensitivity and specificity for a given cut-off value; (3) were conducted in LMICs; and (4) compared screening results to diagnostic classifications based on a reference standard. Screening tool, cut-off, disorder, region, country, and clinical population were extracted for each study, and we assessed study quality. Accuracy results were organized based on screening tool, cut-off, and specific disorder. Accuracy estimates for the same cut-off for the same screening tool and disorder were combined via meta-analysis.

Results

Of 6322 unique citations identified, 58 articles including 77 screening tools were included. There were 46, 19 and 12 validations for anxiety, PTSD, and combined depression and anxiety, respectively. Continentally, Asia had the most validations (35). Regionally, South Asia (11) had the most validations, followed by South Africa (10) and West Asia (9). The Kessler-10 (7) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) (6) were the most commonly validated tools for anxiety disorders, while the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (3) and Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (3) were the most commonly validated tools for PTSD. Most studies (29) had the lowest quality rating (unblinded). Due to incomplete reporting, we could meta-analyze results from only two studies, which involved the GAD-7 (cut-off ≥10, pooled sensitivity = 76%, pooled specificity = 64%).

Conclusion

Use of brief screening instruments can bring much needed attention and research opportunities to various at-risk LMIC populations. However, many have been validated in inadequately designed studies, precluding any general recommendation for specific tools in LMICs. Locally validated screening tools for anxiety and PTSD need further evaluation in well-designed studies to assess whether they can improve the detection and management of these common disorders.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registry number CRD42019121794.

Keywords: Anxiety, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Screening tool, Validation, Low-to-middle income countries

Background

Mental health disorders, including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are among the leading contributors to global disability adjusted life years, comprising five of the top twenty contributing disorders [1]. The World Health Organization International Classification of Disease (ICD-11) defines anxiety as a disorder in which there is an extreme and excessive focus on an “anticipated threat” and defines PTSD as a disorder that results from exposure to one or more “horrific events”, both of whose symptoms include apprehension, motor tension and autonomic overactivity [2]. In 2017, it was estimated that over 264 million people experienced an anxiety disorder, with the global prevalence for both anxiety disorders and PTSD ranging from 2.5 to 7% by country [2–4]. Both anxiety and PTSD are widespread common mental disorders (CMDs) that have been shown to cause significant negative health outcomes within various populations and contribute to a large portion of the global disease burden [5, 6]. There are noteworthy discrepancies in quality of life between people diagnosed with anxiety and/or PTSD and those who are not diagnosed with either, such as increased years lived with disability and decreased life expectancy [7–9]. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that the presence of an anxiety disorder or PTSD increases the likelihood of comorbidity with other severe health conditions, such as major depressive disorder and substance use disorder [10, 11].

Anxiety and PTSD in low to middle income countries (LMICs) are highly prevalent and require further study given that access to care is hindered by availability and stigma [12–14]. Prevalence of these disorders is higher within LMICs; roughly 83% of people with mental illnesses globally are living within LMICs [15]. In many LMICs, there is no robust mental healthcare system in place and the number of mental health professionals is sparse [16]. Assessment and diagnosis of psychiatric illnesses thus often falls to primary care and general practitioners who have little training in mental health [16]. Use of brief screening tools have been proposed as a way to improve identification and management of mental health problems, and may be useful in LMICs, especially among populations with elevated risk (e.g., pregnant women, refugees/displaced persons, and youth) within LMIC communities [17–19].

Despite multiple screening instruments for CMDs, there are significantly fewer screening instruments for anxiety and PTSD that have been validated in LMIC populations. Screening instruments that have been validated exclusively in high-income countries may not perform equivalently in LMIC populations, as anxiety and PTSD often present differently in different cultural contexts. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, anxiety and PTSD are described through somatic symptoms as well as spiritual descriptions [20]. Furthermore, differences in clinical presentation may render screening tools less accurate in LMICs. Thus, optimum cut-off scores validated in high income populations may not apply in LMIC populations. For instance, in a sample of 75 participants from Tajikistan [21], the optimal cut-off of 1.88 for the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), a measure of PTSD, was substantially lower than the standard cut-off score of 2.5 that has been recommended in previous studies in high-income countries [22]. Failure to apply suitable cut-off scores may lead to an imbalance of positive and negative screening results. If chosen cutoffs are too high, actual cases of anxiety and PTSD may not reach the threshold for further assessment and diagnosis; thus, cases will be missed. Conversely, if chosen cutoffs are too low, there may a very large number of positive screens requiring substantial resources for further assessment, and healthcare systems may not be able to manage the load.

Although there has been an increasing interest in studying mental health within LMICs, there are still large gaps related to screening tools to assess mental health disorders, especially anxiety and PTSD. The most recent systematic review investigating screening tools for CMDs in LMICs was published in 2016 [23]. Of the 273 validations included, 236 were validated tools for CMDs or depressive disorders while only 24 and 13 validated tools for anxiety and PTSD, respectively. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of screening tools for anxiety and PTSD within LMIC populations.

Methods

Aim: To validate screening tools for anxiety disorders and PTSD in LMICs.

We published a study protocol in advance in the PROSPERO registry (CRD42019121794).

Search strategy and study selection

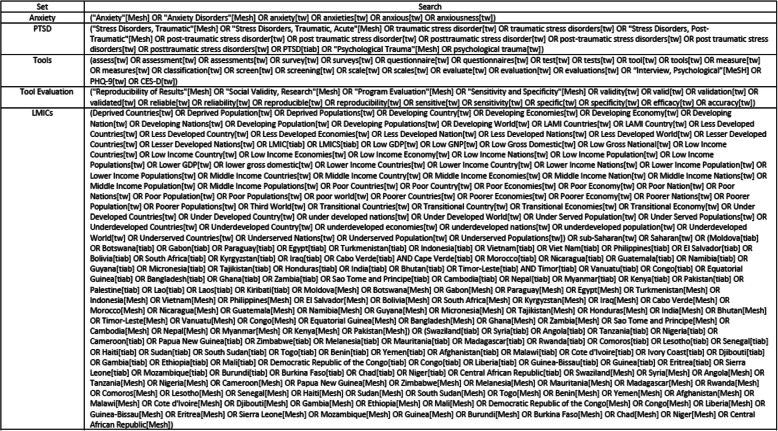

We systematically searched four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health and PsychINFO) from inception to April 22, 2020 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Search strategy

Inclusion criteria

Our eligibility criteria required that studies: (1) screen specifically for anxiety (generalized anxiety disorder or anxiety disorders not otherwise specified) and/or PTSD; (2) provide estimates of sensitivity and specificity for a given cut-off value for one of the included disorders; (3) were conducted in a LMIC (based on the World Bank Classification) [24]; and (4) compare screening results to a validated reference standard. Reference standards included unstructured clinical diagnostic interviews as well as structured clinical interviews including the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI and MINI-KID) [25], Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID, SCID-1 and NetSCID) [26, 27], Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI and CIDI-PHCV) [28], Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R) [29], Psychiatric Assessment Schedule (PAS) [30], Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS and K-SADS-PL) [31] and Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS and CAPS-5) [32, 33]. LMIC populations residing in a LMIC at the time of study were included. No search restrictions were put on age, gender or comorbidities.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded papers that did not report sensitivity, specificity and cut-off value; that were not published in English; and that involved populations originally from an LMIC residing outside a LMIC at the time of the study. Persons from an LMIC residing in another LMIC at the time of the study were included (e.g., refugee populations and displaced persons).

Literature review

Abstracts returned from the search were reviewed separately by two independent reviewers for inclusion, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion and use of a third senior reviewer as needed. For abstracts meeting inclusion criteria, full-text articles were retrieved and reviewed by two separate reviewers for final inclusion, with discrepancies resolved by discussion and use of a third senior reviewer as needed. We also searched the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews for additional articles to add to our full-text review.

Quality appraisal

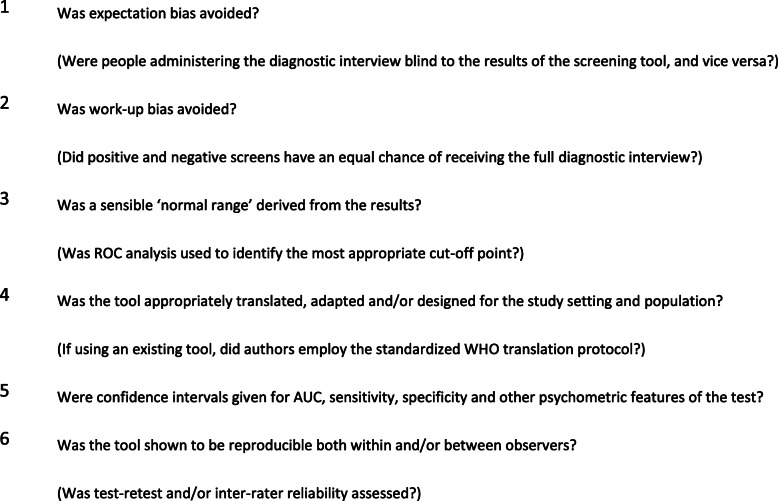

To assess study quality, we used a modified version of Greenhalgh’s ten item checklist previously used in a study by Ali et al. [23] Elements of the quality checklist are provided in Fig. 2. Credit was given for translation if a previously validated translated version of the tool or reference standard was used, or if the tool was administered in English. Studies of ‘very good’ quality fulfilled all the quality criteria. Studies deemed ‘good’ quality fulfilled criteria 1 through 3 in addition to at least one other criterion from 4 to 5. ‘Fair’ quality studies did not avoid work-up bias and ‘acceptable’ quality studies did not perform receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis to determine a normal range from the results. ‘Unblinded’ studies include studies that reported the interviewers were not blinded to the screening results; if the study did not specify whether the screening tool administrators and interviewers were blinded to each other’s results, we considered it unblinded but clarified this designation was unconfirmed.

Fig. 2.

A modified Greenhalgh’s ten item checklist, adapted from Ali et al. [23]

Data abstraction and analysis

Numerical data was abstracted by one reviewer and checked by a separate reviewer to ensure quality extraction. Data abstraction sheets included extraction of the screening tool and disorder, number of participants, DSM version, screening tool administrator, language, region, population study characteristics and age, country, gold standard, area under the curve (AUC), cut-off score, sensitivity and specificity. If multiple screening tools and/or cut-offs were used, data was extracted for each cutoff, for each tool, separately. If values were split by population, the value most representative of the total was chosen (e.g., community values for data split by hospital inpatient unit). If multiple cut-offs were given without AUC, we extracted the set of values for the cutoff that maximized Youden’s J [34]. Results were presented separately by disorder, screening tool and cut-off value. As anxiety and depression were combined in many screening tools, a third category of mixed anxiety and depression was included.

For validations of screening tools for the same disorder that used identical cut-off values, bivariate random-effects meta-analytic models were fitted to provide estimates of pooled sensitivity and specificity for the cut-off value.

Results

Study selection

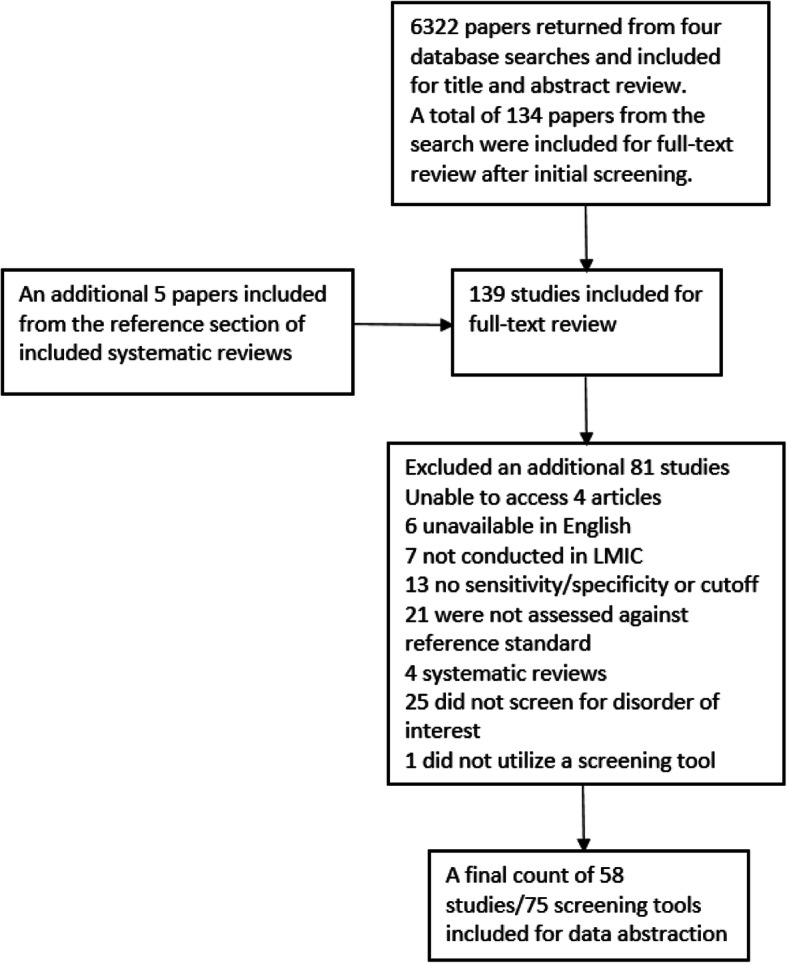

Of 6322 unique citations identified from the database search, 6188 were excluded after title and abstract review and five additional papers from the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews were added. Of 140 included for full-text review, 81 were excluded, leaving 59 eligible articles inclusive of 77 screening tools (see Fig. 3). The most common reasons for exclusion were not screening for the disorder of interest, not comparing to a gold standard, and failing to provide either sensitivity/specificity data or a threshold for screening.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of study selection

Quality appraisal

Two studies met all the criteria of the modified Greenhalgh’s ten item checklist and deemed ‘very good’ quality while 20 studies were deemed to be ‘good’ quality, due to lack of reporting the confidence intervals for sensitivity, specificity or AUC. Two studies were ‘fair’ quality for not avoiding work-up bias and five were deemed ‘acceptable’ for failing to perform ROC analysis. A total of 29 studies were labelled ‘unblinded’ for failing to specify if they blinded the researchers or for explicitly stating they were not blinded (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality rating statistics

| Quality Rating | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| Very good | 2 |

| Good | 20 |

| Fair | 2 |

| Acceptable | 5 |

| Unblinded | 29 |

| Total | 58 |

Description of included studies

The final 59 studies selected included a total of 77 screening tools. There were 46 validations of screening tools for anxiety disorders, 19 for PTSD and 12 for anxiety and depression (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Screening tool validation by disorder category

| Disorder Category | Specific disorders | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders | Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 46 |

| Panic Disorder | ||

| Social Anxiety Disorder | ||

| Anxiety Disorder NOS | ||

| PTSD | PTSD | 19 |

| Anxiety and Depression | Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 12 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | ||

| Total | 77 |

A minority of studies accounted for children and adolescent validations (10) despite a relatively young demographic present in LMICs [35]. The majority of validations studied adults (36), with a select few including adolescents and adults (6) (see Table 3). Particularly well-represented groups included the general population and clinical outpatients (13), perinatal populations (6), psychiatric patients (7) and those with another psychiatric comorbidity (7) (see Table 3). Of the 19 validations for PTSD, only four studied children and adolescents.

Table 3.

Distribution by age a population characteristic

| Population Descriptors | Number of Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Adults (36) | Outpatients | 5 |

| General Population | 7 | |

| HIV | 4 | |

| Psychiatric patients | 7 | |

| Conflict area/refugee | 4 | |

| Other or unspecified | 9 | |

| Perinatal (6) | HIV | 1 |

| Other | 5 | |

| Adolescents and Adults (6) | Survivors of natural disaster | 2 |

| Other | 4 | |

| Children and/or Adolescents (10) | Psychiatric Patient | 2 |

| Survivor of natural disaster | 2 | |

| Other | 6 |

The majority of screening tool validations were in Asia (35) followed by Africa (20), the Americas (5) and Europe (1) (see Table 4). The best represented regions include South and West Asia, as well as South and East Africa, with a noticeable gap in Middle and Northern Africa. There were no studies from the Oceanic region.

Table 4.

Number of Studies by Region and Country

| Continent | Region | Country (Number of Studies) | LMICs with no studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa (20) | North | None | 6 (Sudan, Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia) |

| Middle | None | 9 (Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Sao Tome and Principe) | |

| East (8) | Zimbabwe (2), Somalia (1), Uganda (1), Burundi (1), Tanzania (1), Zambia (1), Ethiopia (1) | 10 (Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, South Sudan) | |

| West (2) | Nigeria (2) | 14 (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cote dIvoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo) | |

| South (10) | South Africa (10) | 4 (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland) | |

| Asia (35) | East (7) | China (7) | 2 (North Korea, Mongolia) |

| South (11) | Pakistan (2), India (3), Nepal (3), Afghanistan (1), Iran (2) | 4 (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Sri Lanka) | |

| South East (7) | Vietnam (3), Malaysia (2), Indonesia (1), Thailand (1) | 4 (Cambodia, Laos, Philippines, Timor-Leste) | |

| West (9) | Kuwait (1), Lebanon (3), Turkey (4), Iraq (1) | 7 (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Jordan, Palestine, Syria, Yemen) | |

| Central (1) | Tajikistan (1) | 4 (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) | |

| America (5) | South (4) | Brazil (2), Peru (2) | 6 (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Suriname) |

| Central (1) | Mexico (1) | 7 (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama) | |

| Caribbean | None | 6 (Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica) | |

| Europe (1) | Southern (1) | Bosnia and Herzegovina (1) | 4 (Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia) |

| Eastern | None | 5 (Belarus, Bulgaria, Moldova, Romania, Ukraine) | |

| Oceania | None | 2 (Melanesia, Micronesia) | |

| Total (61a) |

aThe country total is 61 instead of 58 as one study [36] involved four countries (Mexico, China, Brazil and Pakistan)

The most commonly used tools to screen for generalized anxiety disorder were the Kessler-10 (K-10) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7), totaling seven and six validations respectively. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 item scale (HSCL-25), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety subscale (HADS-A) were validated almost equally while the majority of tools only had one validation (see Table 5). PTSD had far fewer validations (19) with a wide range of tools receiving between one and three validations, similar to the screening tools validated for both anxiety and depression.

Table 5.

Screening Tool by Disorder and Number of Validations

| Disorder | Screening Tool | Number of Validations |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | HADS-A | 3 |

| HADS | 3 | |

| DASS-A | 1 | |

| Zung SAS | 2 | |

| STAI | 1 | |

| EPDS | 2 | |

| HAM-A | 1 | |

| K10 | 7 | |

| K6 | 3 | |

| PHQ-4 | 1 | |

| GAD-7 | 6 | |

| HDRS | 1 | |

| HSCL-25 | 4 | |

| MINI-SPIN | 1 | |

| PHC | 1 | |

| GHQ-12 | 2 | |

| SCARED/SCARED-C/−P | 1/1/1 | |

| PASS | 1 | |

| RCADS-GAD scale | 1 | |

| BAI | 2 | |

| Total | 46 | |

| PTSD | HTQ/−R | 1 |

| HTQ | 3 | |

| K10 | 2 | |

| PDS | 3 | |

| PCL-C/−5 | 2/2 | |

| CPSS | 2 | |

| TSSC | 1 | |

| UCLA PTSD Index | 1 | |

| PTSD Screening Tool | 2 | |

| Total | 19 | |

| Anxiety and Depression | HSCL-25 | 2 |

| Independently developed (Zambia) | 1 | |

| YSR | 1 | |

| HADS | 1 | |

| AKUADS | 1 | |

| SRQ-20 | 1 | |

| AYMH | 1 | |

| HEI | 1 | |

| K10/K6 | 1/1 | |

| PHQ-4 | 1 | |

| Total | 12 |

Abbreviations: HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Anxiety subscale, DASS Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, Zung SAS Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, STAI State Trait Anxiety Inventory, EPDS Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, K10/K6 Kessler 10/6, GAD Generalized Anxiety Test, HDRS Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HSCL Hopkins Symptom Checklist, MINI-SPIN Mini-Social Phobia Inventory, PHC Primary Health Care Screening Tool, GHC General Health Questionnaire, SCARED Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders, PASS Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale, RCADS Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scales, BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory, HTQ Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, PDS Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, PCL-C PTSD Checklist-Clinician Version, PHQ-4 Patient Health Questionnaire, CPSS Child PTSD Symptom Scale, TSSC Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale, YSR Youth Self-Report, AKUADS Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression, SRQ Self-Reporting Questionnaire, AYMH Arab Youth Mental Health Scale, HEI Huaxi Emotional-Distress Index

Each included study is listed in Table 6 by region, screening tool and study quality with the respective sensitivity, specificity and cut-off for each disorder. Continentally, Asia had the most validations (35) and the majority of studies were considered unblinded (29). Due to incomplete reporting, we could meta-analyze results from only two studies, which involved the GAD-7; using a cut-off ≥10; sensitivity = 76%, specificity = 64%.

Table 6.

Included studies listed by continent, sub-region, screening tool/disorder and quality

| Author (year) | Screening tool/disorder | Gold Standard | Subregion | Country | Population | Study Quality | No. Participants | Prevalence (%) | DSM Version | AUC | Cut-Off Score (≥) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||||||||||||

| Ventevogel et al. (2014) [37] | CPSS/PTSD | K-SADS-PL | Africa East | Burundi | Children aged 10–15 | good | 65 | 23 | DSM 4 | 0.78 | 26 | 71 | 83 |

| Chibanda et al. (2016) [38] | GAD-7/GAD | SCID | Africa East | Zimbabwe | Adults except pregnant women | good | 264 | 3 | DSM 4 | 0.9 | 10 | 89 | 73 |

| Kaaya et al. (2002) [39] | HSCL-25/Anxiety and depression | SCID | Africa East | Tanzania | Pregnant women with HIV | good | 903 (100 for SCID) | 3.3 | DSM 4 | 0.86 | 1.06 | 89 | 80 |

| Verhey et al. (2018) [40] | PCL-5/PTSD | CAPS-5 | Africa East | Zimbabwe | Adults except perinatal women | very good | 204 | 19.6 | DSM 5 | 0.78 | 33 | 74.5 | 70.6 |

| Odenwald et al. (2007) [41] | PDS/PTSD | CIDI | Africa East | Somalia | Patients with trauma exposure | good | 135 (62 for CIDI) | 16.1 | DSM 4 | 0.874 | 14 | 90 | 79 |

| Ertl et al. (2011) [42] | PDS/PTSD | CAPS | Africa East | Uganda | Adults and adolescents aged 12–25 | good | 68 | 32.4 | DSM 4 | 0.79 | 16 | 82 | 70 |

| Mbewe et al. (2013) [43] | self-made/Anxiety and depression | Interview | Africa East | Zambia | Adults with epilepsy | good | 575 | 53.7 | DSM 4 | x | 17 | 56.5 | 68.1 |

| Geibel et al. (2016) [44] | YSR/anxiety and depression | Interview | Africa East | Ethiopia | Vulnerable teens assisted by two aid organizations | good | 134 | 64.6 | DSM 4 | 0.729 | 6.5 | 75 | 63.1 |

| Saal (2019) [45] | Beck Anxiety Inventory/GAD | SCID | Africa South | South Africa | Adults undergoing HIV testing | unblinded* | 500 | 3.4 | DSM 5 | 0.86 | 21.5 | 82 | 80 |

| van Heyningen et al. (2018) [46] | EPDS/anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adult women in the antenatal period | unblinded* | 376 | 23 | DSM 4 | 0.69 | 5 | 67 | 59 |

| Marsay et al. (2017) [47] | EPDS/anxiety | NetSCID | Africa South | South Africa | Adult women pregnant for 22–28 weeks | unblinded* | 145 | 14.5 | DSM 5 | x | 7 | 54.8 | 81.6 |

| van Heyningen et al. (2018) [46] | GAD-2/anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adult women in the antenatal period | unblinded* | 376 | 23 | DSM 4 | 0.73 | 2 | 64 | 74 |

| Seedat et al. (2007) [48] | HADS-A/anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adult schizophrenic patients | unblinded | 70 | 22.9 | DSM 4 | x | 11 | 37.5 | 72.2 |

| Seedat et al. (2007) [48] | HAM-A/anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adult schizophrenic patients | unblinded | 70 | 22.9 | DSM 4 | x | 22 | 31.3 | 90.7 |

| Myer et al. (2008) [49] | HTQ/PTSD | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | good | 465 | 5 | DSM 4 | 0.74 | 62 | 74 | 70 |

| Spies et al. (2009) [50] | K-10/Agoraphobia | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded* | 429 | 18.4 | DSM 7 | 0.69 | 26 | 65 | 67 |

| van Heyningen et al. (2018) [46] | K10/anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adult women in the antenatal period | unblinded* | 376 | 23 | DSM 4 | 0.77 | 11 | 76 | 70 |

| Andersen et al. (2011) [51] | K-10/Anxiety and Depression | CIDI | Africa South | South Africa | Adults | unblinded | 4077 | x | DSM 4 | 0.73 | 16 | 70 | 67 |

| Spies et al. (2009) [52] | K10/GAD | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded* | 429 | 18.4 | DSM 4 | 0.78 | 30 | 72 | 80 |

| Spies et al. (2009) [50] | K-10/GAD | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded* | 429 | 18.4 | x | 0.78 | 30 | 72 | 80 |

| Spies et al. (2009) [50] | K-10/Panic disorder | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded* | 429 | 15.3 | DSM 6 | 0.77 | 28 | 76 | 73 |

| Spies et al. (2009) [52] | K-10/PTSD | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded* | 429 | 21.5 | DSM 8 | 0.77 | 29 | 75 | 78 |

| Spies et al. (2009) [50] | K-10/PTSD | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded* | 429 | 21.5 | x | 0.77 | 29 | 75 | 78 |

| Spies et al. (2009) [50] | K-10/Social anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded* | 429 | 12.3 | DSM 5 | 0.9 | 30 | 92 | 80 |

| van Heyningen et al. (2018) [46] | K6/anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adult women in the antenatal period | unblinded* | 376 | 23 | DSM 4 | 0.77 | 8 | 69 | 76 |

| Andersen et al. (2011) [51] | K-6/Anxiety and Depression | CIDI | Africa South | South Africa | Adults | unblinded | 4077 | x | DSM 4 | 0.72 | 10 | 70 | 62 |

| Martin et al. (2009) [53] | PDS/PTSD | CIDI | Africa South | South Africa | HIV-positive adults | unblinded | 85 | x | DSM 4 | 0.74 | 15 | 68.6 | 65 |

| van der Westhuizen (2016) [54] | SRQ-20/Anxiety/Depression | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adults with assault-related injury or accidents | unblinded* | 200 | x | ICD 10 | 0.87 | 5 | 83.3 | 76 |

| Seedat et al. (2007) [48] | STAI/anxiety | MINI | Africa South | South Africa | Adult schizophrenic patients | unblinded | 70 | 22.9 | DSM 4 | x | 40 | 75 | 48.1 |

| Makanjuola et al. (2014) [55] | GHQ-12/anxiety | CIDI | Africa West | Nigeria | Adult patients of general practices | unblinded | 1590 | x | DSM 4 | 0.61 | 3 | 59 | 63.3 |

| Abiodun et al. (1994) [56] | HADS/Anxiety and Depression | Interview | Africa West | Nigeria | Adult patients in non-psychiatric wards and community | unblinded* | 1078 | Various† | ICD 9 | x | 8 | 87.5 | 90.6 |

| Makanjuola et al. (2014) [55] | K6/anxiety | CIDI | Africa West | Nigeria | Adult patients of general practices | unblinded | 1590 | x | DSM 4 | 0.58 | 4 | 65 | 55 |

| Asia | |||||||||||||

| Hollander et al. (2007) [21] | HSCL-25/anxiety | Interview | Asia Central | Tajikistan | Adult patients at outpatient clinics | acceptable | 75 | x | DSM 4 | x | 1.6 | 84 | 60 |

| Hollander et al. (2007) [21] | HTQ-R/PTSD | Interview | Asia Central | Tajikistan | Adult patients at outpatient clinics | acceptable | 75 | x | DSM 4 | x | 1.73 | 97 | 65 |

| Tong et al. (2016) [57] | GAD-7/Generalized anxiety | MINI | Asia East | China | Adults with epilepsy who were Chinese citizens | unblinded | 213 | 23.5 | DSM 4 | 0.974 | 6 | 94 | 91.4 |

| Sheng et al. (2010) [58] | HADS-A/anxiety | MINI | Asia East | China | Adult psychiatric outpatients | unblinded | 70 | 25.5 | DSM 4 | 0.805 | 6 | 86 | 79 |

| Yang et al. (2014) [59] | HADS-A/anxiety | MINI | Asia East | China | Adult cardiac outpatients | unblinded* | 100 | 15 | DSM 4 | 0.81 | 6 | 81.6 | 75.8 |

| Wang et al. (2017) [60] | HEI/Anxiety and depression | MINI | Asia East | China | Hospitalized patients aged 15+ | unblinded* | 763 | 7.11 | DSM 4 | 0.88 | 11 | 88 | 76.6 |

| Liu et al. (2008) [61] | PTSD screening tool/PTSD | DSM-IV PTSD criteria | Asia East | China | Survivors of a flood aged 16+ | unblinded | 27,267 | 9.5 | DSM 4 | 0.858 | 3 | 87.9 | 97.9 |

| Liu et al. (2007) [62] | PTSD screening tool/PTSD | DSM-IV PTSD criteria | Asia East | China | Child survivors of a flood aged 7–15 | unblinded | 6073 | 4.6 | DSM 4 | x | 3 | 96.9 | 99 |

| Ali et al. (1998) [63] | AKUADS/GAD and MDD | Interview | Asia South | Pakistan | Residents aged 16–60 in Karachi squatter settlement | unblinded | 487 | x | DSM 3 | x | 19 | 74 | 81 |

| Kohrt et al. (2003) [64] | BAI/anxiety | DSM-IV criteria | Asia South | Nepal | Adults with psychiatric illness and controls | acceptable | 363 | Various† | DSM 4 | x | 14 | 91 | 89 |

| Thapa et al. (2005) [65] | PCL-C/PTSD | CIDI | Asia South | Nepal | Adults residing in conflict areas | unblinded | 290 | 53.4 | DSM 4 | 0.81 | 50 | 80 | 80 |

| Kohrt et al. (2011) [66] | CPSS/PTSD | K-SADS | Asia South | Nepal | Adolescents aged 11–14 | good | 162 | 6.4 | DSM 4 | 0.77 | 20 | 68 | 73 |

| Chaturvedi et al. (1994) [67] | HADS/anxiety | Interview | Asia South | India | Cancer patients of all ages | unblinded* | 70 | not specified | DSM 3 | x | 7 | 87 | 79 |

| Ventevogel et al. (2007) [68] | HSCL/anxiety | PAS | Asia South | Afghanistan | Clinic patients aged 15+ | good | 116 | 24.1 | x | 0.61 | 2 | 75 | 43 |

| Ventevogel et al. (2007) [68] | HSCL/depression and anxiety | PAS | Asia South | Afghanistan | Clinic patients aged 15+ | good | 116 | 24.1 | x | 0.61 | 2 | 69 | 67 |

| Housen et al. (2018) [69] | HSCL-25/anxiety | MINI | Asia South | India | Adult general medical outpatients | good | 290 | 3.5 | DSM 4 | 0.81 | 1.75 | 73 | 81 |

| Thapa et al. (2005) [65] | HSCL-25/anxiety | CIDI | Asia South | Nepal | Adults residing in conflict areas | unblinded | 290 | 80.7 | DSM 4 | 0.76 | 1.75 | 77 | 58 |

| Ahmadi (2020) [70] | PHQ-4/anxiety | SCID | Asia South | Iran | Adults with coronary heart disease | unblinded* | 279 | not specified | DSM 5 | 0.94 | 7 | 80 | 94 |

| Ahmadi (2020) [70] | PHQ-4/Anxiety and depression | SCID | Asia South | Iran | Adults with coronary heart disease | unblinded* | 279 | not specified | DSM 5 | 0.94 | 7 | 86 | 90 |

| Russell et al. (2013) [71] | SCARED/anxiety | K-SADS-PL | Asia South | India | Adolescents aged 11–19 | unblinded* | 500 | x | DSM 4 | 0.9 | 21 | 84.6 | 87.36 |

| Namazi et al. (2013) [72] | UCLA PTSD (PTSD) | Interview | Asia South | Iran | Children aged 7–12 after earthquake | unblinded* | 50 | 56 | 4-R | x | 38 | 96 | 50 |

| Tran et al. (2013) [73] | DASS-A/anxiety | SCID | Asia South East | Vietnam | Adult perinatal women | good | 221 | 10.9 | DSM 4 | 0.806 | 10 | 79.2 | 67 |

| Sidik et al. (2012) [74] | GAD-7/anxiety | CIDI | Asia South East | Malaysia | Adult females | good | 895 | 7.8 | DSM 4 | x | 8 | 76 | 94 |

| Yahya et al. (2015) [75] | HDRS/anxiety | DSM-IV | Asia South East | Malaysia | Patients with existing psychiatric disorder and controls | unblinded* | 120 | x | DSM 4 | 0.917 | 8 | 90 | 86.2 |

| Silove et al. (2007) [76] | HTQ/PTSD | SCID | Asia South East | Thailand | Cambodian population in Thailand | good | 118 | 20.3 | DSM 4 | 0.71 | 2 | 63 | 61 |

| Tran et al. (2019) [77] | K-10/anxiety | MINI-KID | Asia South East | Indonesia | Adolescents age 16–18 | unblinded* | 196 | x | DSM 4 | 0.82 | 18 | 87.1 | 70.9 |

| Tran et al. (2019) [77] | K-6/anxiety | MINI-KID | Asia South East | Indonesia | Adolescents age 16–19 | unblinded* | 196 | x | DSM 4 | 0.8 | 12 | 83.9 | 73.3 |

| Tran et al. (2011) [78] | Zung SAS/anxiety | Interview | Asia South East | Vietnam | Adult perinatal women | good | 364 | 11.8 | DSM 4 | 0.79 | 38 | 67.9 | 75.3 |

| Tran et al. (2012) [79] | Zung SAS/anxiety | Interview | Asia South East | Vietnam | Men who are partners of pregnant or perinatal women | good | 231 | 5.2 | DSM 4 | 0.775 | 36 | 70.7 | 79 |

| Mahfoud et al. (2011) [80] | AYMH/Anxiety and depression | Interview | Asia West | Lebanon | Socioeconomically disadvantaged children aged 10–14 | good | 153 | 17.6 | DSM 4 | 0.71 | 39 | 63 | 79 |

| Sawaya et al. (2016) [81] | GAD-7/anxiety | Interview | Asia West | Lebanon | Adult psychiatric outpatients | acceptable | 176 | x | DSM 4 | 0.57 | 10 | 57 | 53 |

| Senturk et al. (2007) [82] | GHQ-12/anxiety | CIDI-PHCV | Asia West | Turkey | Adult leprosy patients | unblinded* | 65 | 12.3 | ICD 10 | 0.69 | 5 | 71 | 57 |

| Malasi et al. (1991) [83] | HADS/anxiety | Interview | Asia West | Kuwait | Adult psychiatric outpatients and controls | acceptable | 135 | x | DSM 3 | 13 | 45 | 47 | |

| Senturk et al. (2007) [82] | HADS/anxiety | CIDI-PHCV | Asia West | Turkey | Adult leprosy patients | unblinded* | 65 | x | ICD 11 | 0.75 | 11 | 66 | 58 |

| Yazici et al. (2018) [84] | PASS/anxiety | SCID-1 | Asia West | Turkey | Adult women in perinatal period | unblinded* | 312 | 19.2 | DSM 4 | 0.94 | 16 | 95 | 84 |

| Ibrahim et al. (2018) [85] | PCL-5/PTSD | DSM 5 interview | Asia West | Iraq | Adults living in a camp for displaced people in Iraq | good | 206 | 37.75 | DSM 5 | 0.82 | 23 | 82 | 70 |

| Gormez et al. (2017) [86] | RCADS-GAD scale/GAD | K-SADS | Asia West | Turkey | Child psychiatry outpatients aged 8–17 | unblinded* | 483 | not specified | DSM 4 | x | 7.5 | 70 | 71 |

| Hariz et al. (2013) [87] | SCARED-C/anxiety | Interview | Asia West | Lebanon | Child and adolescent psychiatric patients | good | 82 | 40.2 | DSM 4 | 0.63 | 26 | 66 | 56 |

| Hariz et al. (2013) [87] | SCARED-P/anxiety | Interview | Asia West | Lebanon | Child and adolescent psychiatric patients | good | 82 | x | DSM 4 | 0.7 | 24 | 67 | 55 |

| Başoglu et al. (2001) [88] | TSSC/PTSD | CAPS | Asia West | Turkey | Survivors of 1999 August earthquake aged 16–70 | acceptable | 130 | 49 | DSM 4 | x | 2 | 76 | 73 |

| Europe | |||||||||||||

| Oruc et al. (2008) [89] | HTQ/(PTSD) | SCID | Europe Southern | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Adults enrolled in primary care clinic | very good | 180 | 26 | DSM 4 | 0.98 | 2.06 | 99.9 | 93.9 |

| South America | |||||||||||||

| Zhong et al. (2015) [90] | GAD-7/GAD | CIDI | South America | Peru | Pregnant women aged 18–49 who speak Spanish | unblinded* | 946 | 33.3 | DSM 4 | 0.75 | 7 | 73.3 | 67.3 |

| de Lima Osório et al. (2007) [91] | MINI-SPIN/Social anxiety disorder | SCID | South America | Brazil | University students | fair | 2320 | 10.4 | DSM 4 | 0.81 | 6 | 94 | 46 |

| Gelaye et al. (2017) [92] | PCL-C/PTSD | CAPS | South America | Peru | Perinatal women | very good | 3289 | 3 | DSM 4 | 0.75 | 26 | 86 | 63 |

| Multiple Countries | |||||||||||||

| Goldberg et al. (2017) [36] | PHC/current anxiety | CIS-R | South America, Asia South, Asia East, Central America | Brazil, Pakistan, China, Mexico | Primary care patients | fair | 1488 (all countries) | Brazil: 26.5; Pakistan: 13; China: 18.9; Mexico: 23 | ICD 11 | 0.77 | 3 | 75 | 68 |

| Meta-analyzed GAD-7 Values | |||||||||||||

| Chibanda et al. (2016) [38] and Sawaya et al. (2016) [81] | GAD-7/anxiety | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ≥10 | 76 | 64 |

Quality: ranges from highest to lowest (very good, good, fair, acceptable, unblinded, unblinded* (unblinded [unconfirmed so considered unblinded]); x: value not specified; various†: multiple values specified, see Appendix file; Abbreviations: HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Anxiety subscale, DASS Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, Zung SAS Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, STAI State Trait Anxiety Inventory, EPDS Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, K10/K6 Kessler 10/6, GAD Generalized Anxiety Test, HDRS Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HSCL Hopkins Symptom Checklist, MINI-SPIN Mini-Social Phobia Inventory, PHC Primary Health Care Screening Tool, GHC General Health Questionnaire, SCARED Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders, PASS Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale, RCADS Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scales, BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory; HTQ Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, PDS Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, PCL-C PTSD Checklist-Clinician Version, PHQ-4 Patient Health Questionnaire, CPSS Child PTSD Symptom Scale, TSSC Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale, YSR Youth Self-Report, AKUADS Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression, SRQ Self-Reporting Questionnaire, AYMH Arab Youth Mental Health Scale, HEI Huaxi Emotional-Distress Index

Discussion

This review aimed to examine the screening tools that have been validated to detect anxiety and PTSD in LMICs. The most commonly validated tools were the K-10 and GAD-7 for anxiety and the HTQ and the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) for PTSD. It is difficult to recommend one screening tool for anxiety and PTSD respectively, as various tools and cut-off values were tested, and sensitivities and specificities varied based on region, country and screening tool. Indeed, only two studies tested the same tool using the same cut-off value and reported sufficient information to allow us to quantitatively synthesize the results. Locally validated screening tools for anxiety and PTSD need further evaluation in well-designed studies to assess whether they can improve the detection and management of these common disorders.

A total of 46 validated screening tools were found for anxiety disorders. The most common tool used to screen for anxiety disorders was the Kessler-10 followed by the GAD-7, which had wide ranges of sensitivities (57–94%) and specificities (53–94%) varying by region and sample size. While previously the HADS-A was recommended [23], our updated review found that it was not as widely validated as the GAD-7 and Kessler-10, although it had consistent specificities (72–79%) with a range of sensitivities (38–86%). The Kessler may have an added time-efficiency component, as it is possible to screen for multiple common mental disorders, whereas screening tools such as the HADS-A target anxiety specifically. The GAD-7 reported some of the highest sensitivities for detection of generalized anxiety disorder. Other anxiety disorders, including agoraphobia, panic disorder and social anxiety disorder were less commonly validated. Our results are consistent with a previous systematic review [23] and indicate using the GAD-7, K-10 or HAD-A yield good sensitivities and specificities while taking population-specific characteristics into account. Future research is needed to validate screening tools for these anxiety disorders in more regions.

The number of validations for PTSD increased from 10 to 19 since 2013 [23]. The HTQ and PDS were the most commonly validated tools for PTSD, and sensitivities were generally high. Our findings add that in addition to the previously recommended HTQ, the PDS should be considered in screening for PTSD [23]. Unfortunately, many tools were validated only once, preventing our combining them for analytic purposes. Only four PTSD validations describe children and adolescents, despite recent events that have displaced thousands of youth [93]. The prevalence of PTSD remains high in LMICs and is expected to rise given increasing civil unrest and war [19, 94]. The year 2018 saw the highest recorded number of displaced persons globally leading the authors to emphasize more attention into detection and treatment of PTSD [95].

Anxiety and depression had the fewest validations across our search [11] though were not the target of our validation given the existing literature on depression alone [23]. All tools with the exception of the HSCL-25 had only one validation. The only independently developed screening tool of all the studies was for anxiety and depression, developed in Zambia. These disorders commonly occur together, and further research is needed to determine which tools are best suited to a region’s mental health screening needs.

We searched four databases with a robust library of psychiatric publications available. We also placed minimal exclusion criteria on our searches so as to maximize the number of studies returned, and we additionally reviewed relevant systematic reviews for additional relevant papers. At every stage of the process from title/abstract screen to data abstraction, two reviewers assessed each article and numerical data point to reduce human error. Our search strategy and protocol were published in PROSPERO and were not altered from the time of submission, with the exception that we did not calculate diagnostic odds ratios (DORs), as they provide no guidance to clinicians on what screening tool and cut-off threshold would be most appropriate to use in clinical practice. Rather, we reported sensitivity and specificity of each screening tool and cutoff separately, to better describe the accuracies of individual tools and cut-offs.

Our extraction was limited by the individual papers’ specific data reporting. Varying prevalence of an individual study may affect the cut-off score, sensitivity and specificity of screening tools, and some studies did not publish prevalence. Providers should reference the prevalence of each specific disorder to ascertain whether the cut-off is applicable to their respective population. The majority of studies did not provide sensitivities and specificities for multiple cut-off values. Reporting multiple cut-off values and their respective sensitivity and specificity estimates would allow providers to decide which cut-off they would choose to optimize screening for their setting. A lower cut-off with a higher sensitivity may be desired if cases are not to be missed and false negatives reduced. A higher cut-off with a higher specificity may be desired if false positives are to be minimized. Furthermore, reporting multiple cut-off values and their respective sensitivity and specificity estimates would also allow researchers to better synthesize accuracy results across multiple studies in meta-analysis. In the present study, only two validations with identical cut-off scores for the GAD-7 could be combined via meta-analysis as no other validations of the same disorder with identical cut-off values provided sufficient information to conduct a meta-analysis (i.e., 2 × 2 table numbers). Studies used various versions of the DSM and ICD. While the symptomatology for psychiatric diagnoses have not changed significantly, providers should reference which version was used when conducting the validation of the screening tool (see Table 6).

Our review was also limited by the available publications on mental health screenings in LMICs. The entire region of Middle and North Africa, constituting over 300 million people, was not represented by a single validation while other regions such as South-East Asia were fairly well-represented. Cultural and linguistic factors may influence screening tool validation yet further discussion may be best served for individual validation papers. Most studies were rated in the lowest quality category of the modified Greenhalgh scale as they were unblinded, or downgraded to unblinded due to incomplete reporting. This is a severe limitation in the design of studies that may impact validation results; future studies should ensure adequate blinding in addition to the remainder of the quality checklist.

Our study did not look at CMDs or depression specifically, although we did consider anxiety and depression when screened for together. We chose to focus on anxiety and PTSD as they are less well-represented in the realm of LMIC validated screening tools. Additionally, anxiety and PTSD are becoming more important with the current displacement of millions of people due to civil unrest, socioeconomic upheaval and war.

The number of validated screening tools for mental health disorders as a whole has increased since 2013 [23]. However, no large increase in the number of validations for specific disorders was seen, and most screening tools from our search were validated only once. We advise researchers and providers to refer to Table 6 for a summary of validations for locations and disorders of interest and to use this table to identify their region of interest, find their disease focus of interest, and then identify what tools have been identified by the highest quality evidence.

Conclusions

Mental health disorders are highly prevalent yet are frequently stigmatized and disregarded as medical diseases. Validated screening tools for anxiety and PTSD in LMIC have made considerable progress, with validations for both disorders almost doubling since the prior systematic review completed in December 2013 [23]. The increase in validated screening tools generally followed a regional pattern, with more emerging in countries already represented. For example, more tools have been validated in South Africa without an increase in validations in Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia or Swaziland. Middle and Northern Africa were also not well-represented by either anxiety or PTSD screening tools. The authors recognize that it may be near impossible to validate screening tools in areas of intense conflict and instability but acknowledge the need to evaluate screening tools in these areas.

The age distribution among screening tools was heavily biased towards the adult population. Children and adolescents accounted for only four of 19 validations for PTSD and six of 58 for anxiety and anxiety and depression. Given that age is skewed towards a younger population in LMICs [35], it is imperative that more research focuses on identifying anxiety and PTSD disorders in a pediatric population, especially in areas of increased civil war and conflict.

Use of brief screening instruments can bring much needed attention and research opportunities to various at-risk populations in LMICs. Many screening tools for anxiety and PTSD have been validated in LMICs, but there remain regions and subgroups of individuals for which more research is needed. Locally validated screening tools for anxiety and PTSD should be further evaluated in clinical trials to determine whether their use can reduce the burden of disease.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Rebecca McCall (search strategy aid), UNC Chapel Hill.

Abbreviations

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- LMICs

Low to middle income countries

- CMDs

Common mental disorders

- MINI and MINI-KID

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- SCID, SCID-1 and NetSCID

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM

- CIDI and CIDI-PHCV

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- CIS-R

Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised

- PAS

Psychiatric Assessment Schedule

- K-SADS and K-SADS-PL

Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia

- CAPS and CAPS-5

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale

- AUC

Area under the curve

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- DORs

Diagnostic odds ratios

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- DASS

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

- Zung SAS

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale

- STAI

State Trait Anxiety Inventory

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- HAM-A

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

- K10/K6

Kessler 10/6

- GAD

Generalized Anxiety Test

- HDRS

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- HSCL

Hopkins Symptom Checklist

- MINI-SPIN

Mini-Social Phobia Inventory

- PHC

Primary Health Care Screening Tool

- GHC

General Health Questionnaire

- SCARED

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders

- PASS

Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale

- RCADS

Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scales

- BAI

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- HTQ

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire

- PDS

Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale

- PCL-C

PTSD Checklist-Clinician Version

- CPSS

Child PTSD Symptom Scale

- TSSC

Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale

- CAPS

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale

- YSR

Youth Self-Report

- AKUADS

Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression

- SRQ

Self-Reporting Questionnaire

- AYMH

Arab Youth Mental Health Scale

- HEI

Huaxi Emotional-Distress Index

Authors’ contributions

All authors listed below have read and approved the manuscript. AYM: Design of systematic review, search criteria and primary reviewer, wrote manuscript. JD: Primary reviewer, aided in introduction and editing of manuscript. EA: Primary reviewer, aided in manuscript writing and editing. BL: Data analysis, aided in manuscript writing and editing. VFG: Manuscript writing and editing. 6. BNG: Design of systematic review, development of methods, manuscript writing and editing.

Funding

The Doris Duke Clinical Research Foundation funded the primary author, Ms. Mughal, for the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript through a Doris Duke International Clinical Research Fellowship. Dr. Levis was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship doctoral award, and a Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS) Postdoctoral Training Fellowship.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anisa Y. Mughal, Email: AYM6@pitt.edu

Eric Ardman, Email: eaardman@gmail.com.

Brooke Levis, Email: brooke.levis@gmail.com.

Vivian F. Go, Email: vgo@live.unc.edu

Bradley N. Gaynes, Email: bradley_gaynes@med.unc.edu

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12888-020-02753-3.

References

- 1.Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritchie H, Roser M. Mental Health. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2013;43(5):897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenen KC, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, McLaughlin KA, Bromet EJ, Stein DJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental Health surveys. Psychol Med. 2017;47(3):2260–2274. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Koenen KC, Mclaughlin KA, Health M, Africa S. Epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: prevalence, correlates and consequences. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(4):307–311. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000167.Epidemiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Ghandour RM, Blumberg SJ, Visser SN, Perou R, et al. Epidemiology and impact of health care provider-diagnosed anxiety and depression among. US children. 2019;39(5):395–403. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000571.Epidemiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, Feigin V, Vos T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: An analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes D, McFarlane AC, Silove D, Bryant RA, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M. The lingering impact of resolved PTSD on subsequent functioning. Clin Psychol Sci. 2015;4(3):493–498. doi: 10.1177/2167702615598756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brady K, Killeen T, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:22–32. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v61n0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheffler JL, Rushing NC, Stanley IH, Sachs-Ericsson NJ. The long-term impact of combat exposure on health, interpersonal, and economic domains of functioning. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(11):1202–1212. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1072797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane JC, Elafros MA, Murray SM, Mitchell EMH, Augustinavicius JL, Causevic S, Baral SD. A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 2019;17(1). 10.1186/s12916-019-1250-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Mascayano F, Armijo JE, Yang LH. Addressing stigma relating to mental illness in low- and middle-income countries. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6(38):1–4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wainberg ML, Scorza P, Shultz JM, Helpman L, Mootz JJ, Johnson KA, et al. Challenges and opportunities in global mental Health: a research-to-practice perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(5). 10.1007/s11920-017-0780-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease 2004, vol. 146. Geneva: Update, World Health Organization; 2004.

- 16.Nadkarni A, Hanlon C, Bhatia U, Fuhr D, Ragoni C, de Azevedo Perocco SL, et al. The management of adult psychiatric emergencies in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(6):540–547. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giacco D, Laxhman N, Priebe S. Prevalence of and risk factors for mental disorders in refugees. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;77:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honikman S, Tomlinson M, Field S, van Heyningen T, Myer L, Onah MN. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety disorders amongst low-income pregnant women in urban South Africa: a cross-sectional study. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2017;20(6):765–775. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0768-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yatham S, Sivathasan S, Yoon R, da Silva TL, Ravindran AV. Depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder among youth in low and middle income countries: a review of prevalence and treatment interventions. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;38(August 2017):78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd K, Simunyu E, Mann A, Patel V, Gwanzura F. The phenomenology and explanatory models of common mental disorder: a study in primary care in Harare, Zimbabwe. Psychol Med. 2009;25(06):1191. doi: 10.1017/s003329170003316x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollander AC, Ekblad S, Mukhamadiev D, Muminova R. The validity of screening instruments for posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and other anxiety symptoms in Tajikistan. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(11):955–958. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318159604b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mollica R, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard trauma questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(2):111–116. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali GC, Ryan G, De Silva MJ. Validated screening tools for common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups Website. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed December 3, 2018.

- 25.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M, First M. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brodey BB, First M, Linthicum J, Haman K, Sasiela JW, Ayer D. Validation of the NetSCID: An automated web-based adaptive version of the SCID. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;66:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robins L, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer J, Babor T, Burke J, et al. The composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1142/9789814440912_0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis G, Pelosi A, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22(May):465–486. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss S, Patel P, Prosser H, Goldberg D, Simpson N, Rowe S, Lucchino R. Psychiatric morbidity in older people with moderate and severe learning disability. I: development and reliability of the patient interview (PAS-ADD) Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163(OCT):471–480. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blake DD, Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Gusman F, Charney D, Keane T. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weathers F, Bovin M, Lee D, Sloan D, Schnurr P, Kaloupek D, et al. The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol Assess. 2018;30(3):383–395. doi: 10.1037/pas0000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruopp M, Perkins N, Whitcomb B, Schisterman E. Youden index and optimal cut-point estimated from observations affected by a lower limit od detection. Biom J. n.d.;50(3):419–30. 10.1002/bimj.200710415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Sudharsanan N, Bloom D. The demography of aging in low- and middle-income countries: chronological versus functional perspectives. In: Hayward M, Majmundar M, editors. Future directions for the demography of aging. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. pp. 322–351. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldberg DP, Reed GM, Robles R, Minhas F, Razzaque B, Fortes S, et al. Screening for anxiety, depression, and anxious depression in primary care: a field study for ICD-11 PHC. J Affect Disord. 2017;213(February):199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ventevogel P, Komproe IH, Jordans MJ, Feo P, De Jong JTVM. Validation of the Kirundi versions of brief self-rating scales for common mental disorders among children in Burundi. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chibanda D, Verhey R, Gibson LJ, Munetsi E, Machando D, Rusakaniko S, et al. Validation of screening tools for depression and anxiety disorders in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. J Affect Disord. 2016;198:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaaya SF, Fawzi MCS, Mbwambo JK, Lee B, Msamanga GI, Fawzi W. Validity of the Hopkins symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(1):9–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verhey R, Chibanda D, Gibson L, Brakarsh J, Seedat S. Validation of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist - 5 (PCL-5) in a primary care population with high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1688-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odenwald M, Lingenfelder B, Schauer M, Neuner F, Rockstroh B, Hinkel H, Elbert T. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder among Somali ex-combatants: a validation study. Confl Heal. 2007;1(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Saile R, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Validation of a mental health assessment in an african conflict population. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(2):318–324. doi: 10.1037/a0018810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mbewe EK, Uys LR, Nkwanyana NM, Birbeck GL. A primary healthcare screening tool to identify depression and anxiety disorders among people with epilepsy in Zambia. Epilepsy Behavior. 2013;27(2):296–300. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geibel S, Habtamu K, Mekonnen G, Jani N, Kay L, Shibru J, et al. Reliability and validity of an interviewer-administered adaptation of the youth self-report for mental health screening of vulnerable young people in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saal WL, Kagee A, Bantjes J. Evaluation of the beck anxiety inventory in predicting generalised anxiety disorder among individuals seeking HIV testing in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2019;25:1–5. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v25i0.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Heyningen T, Honikman S, Tomlinson M, Field S, Myer L. Comparison of mental health screening tools for detecting antenatal depression and anxiety disorders in south African women. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marsay C, Manderson L, Subramaney U. Validation of the Whooley questions for antenatal depression and anxiety among low-income women in urban South Africa. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2017;23(1):1–7. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v23i0.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seedat S, Fritelli V, Oosthuizen P, Emsley RA, Stein DJ. Measuring anxiety in patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(4):320–324. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253782.47140.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myer L, Smit J, Le Roux L, Parker S, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(2):147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spies G, Kader K, Kidd M, Smit J, Myer L, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Validity of the K-10 in detecting DSM-IV-defined depression and anxiety disorders among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Care. 2009;21(9):1163–1168. doi: 10.1080/09540120902729965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andersen LS, Grimsrud A, Meyer L, Williams DR, Stein DJ, Seedat S. The psychometric properties of the K10 and K6 scales in screening for mood and anxiety disorders in the south African stress and Health study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(4):215–233. doi: 10.1002/mpr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spies G, Stein DJ, Roos A, Faure SC, Mostert J, Seedat S, Vythilingum B. Validity of the Kessler 10 (K-10) in detecting DSM-IV defined mood and anxiety disorders among pregnant women. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2009;12(2):69–74. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin L, Fincham D, Kagee A. Screening for HIV-related PTSD: sensitivity and specificity of the 17-item posttraumatic stress diagnostic scale (PDS) in identifying HIV-related PTSD among a south African sample. Afr J Psychiatry (South Africa) 2009;12(4):270–274. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v12i4.49041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Westhuizen C, Wyatt G, Williams JK, Stein DJ, Sorsdahl K. Validation of the self reporting questionnaire 20-item (SRQ-20) for use in a low- and middle-income country emergency Centre setting. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2016;14(1):37–48. doi: 10.1007/s11469-015-9566-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Makanjuola VA, Onyeama M, Nuhu FT, Kola L, Gureje O. Validation of short screening tools for common mental disorders in Nigerian general practices. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abiodun AO. A validity study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in general hospital units and a community sample in Nigeria. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165(5):669–672. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tong X, An D, McGonigal A, Park SP, Zhou D. Validation of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;120(February 2020):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheng L. Better detection of non-psychotic mental disorders by case description method in China. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3(4):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Y, Ding R, Hu D, Zhang F, Sheng L. Reliability and validity of a Chinese version of the HADS for screening depression and anxiety in psycho-cardiological outpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(1):215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, Guo W, Jun Zhang L, Deng W, Wang H, Yao Y, Ying J, Li T. The development and validation of Huaxi emotional-distress index (HEI): a Chinese questionnaire for screening depression and anxiety in non-psychiatric clinical settings. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;76:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu A, Tan H, Zhou J, Li S, Yang T, Tang X, et al. A short DSM-IV screening scale to detect posttraumatic stress disorder after a natural disaster in a Chinese population. Psychiatry Res. 2008;159(3):376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu AZ, Tan H, Zhou J, Li S, Yang T, Sun Z, Wen SW. Brief screening instrument of posttraumatic stress disorder for children and adolescents 7-15 years of age. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2007;38(3):195–202. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ali BS, Amanullah S. A comparative review of two screening instruments; the Aga Khan University anxiety and depression scale and the self reporting questionnaire. J Pak Med Assoc. 1998;48(3):79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Koirala NR, Sharman VD, Nepal MK. Validation of the Nepali version of beck anxiety inventory. J Inst Med. 2003;25(3):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thapa SB, Hauff E. Psychological distress among displaced persons during an armed conflict in Nepal. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(8):672–679. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0943-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kohrt BA, Jordans MJ, Tol WA, Luitel NP, Maharjan SM, Upadhaya N. Validation of cross-cultural child mental health and psychosocial research instruments: adapting the depression self-rating scale and child PTSD symptom scale in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(127):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS, Channabasavanna SM, Beena MB. Detection of anxiety and depression in cancer patients. NIMHANS J. 1994;12(2):141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ventevogel P, De Vries G, Scholte WF, Shinwari NR, Faiz H, Nassery R, et al. Properties of the Hopkins symptom checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and the self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ-20) as screening instruments used in primary care in Afghanistan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(4):328–335. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Housen T, Lenglet A, Ariti C, Ara S, Shah S, Dar M, et al. Validation of mental health screening instruments in the Kashmir Valley, India. Transcult Psychiatry. 2018;55(3):361–383. doi: 10.1177/1363461518764487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ahmadi SM, Arani AM, Bakhtiari M, Davazdah Emamy MH. Psychometric properties of Persian version of patient health questionnaires-4 (PHQ-4) in coronary heart disease patients. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2020;13(4). 10.5812/ijpbs.85820.

- 71.Russell PSS, Nair MKC, Russell S, Subramaniam VS, Sequeira AZ, Nazeema S, George B. ADad 2: the validation of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders for anxiety disorders among adolescents in a rural community population in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80(November):S139–S143. doi: 10.1007/s12098-013-1233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Namazi S, Baba MB, Mokhtar HH, Hamzah MSG. Validation of the Iranian version of the University of California at Los Angeles posttraumatic stress disorder index for DSM-IV-R. Trauma Monthly. 2013;18(3):122–125. doi: 10.5812/traumamon.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tran TD, Fisher J, Tran T. Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales ( DASS ) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rural ... Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales ( DASS ) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rur. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(24):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sidik SM, Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Validation of the GAD-7 (Malay version) among women attending a primary care clinic in Malaysia. J Primary Health Care. 2012;4(1):5–11. doi: 10.1071/hc12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yahya F, Othman Z, Fariza Yahya M. Validation of the Malay version of hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia article in. Int Med J Yol. 1994;22(2):80–82. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silove D, Manicavasagar V, Mollica R, Thai M, Khiek D, Lavelle J, Tor S. Screening for depression and PTSD in a Cambodian population unaffected by war: comparing the Hopkins symptom checklist and Harvard trauma questionnaire with the structured clinical interview. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(2):152–157. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000254747.03333.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tran TD, Kaligis F, Wiguna T, Willenberg L, Nguyen HTM, Luchters S, et al. Screening for depressive and anxiety disorders among adolescents in Indonesia: formal validation of the Centre for epidemiologic studies depression scale – revised and the Kessler psychological distress scale. J Affect Disord. 2019;246(August 2018):189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tran TD, Tran T, La B, Lee D, Rosenthal D, Fisher J. Screening for perinatal common mental disorders in women in the north of Vietnam: a comparison of three psychometric instruments. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(1–2):281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J. Validation of three psychometric instruments for screening for perinatal common mental disorders in men in the north of Vietnam. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1–2):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mahfoud Z, Abdulrahim S, Taha MB, Harpham T, El Hajj T, Makhoul J, et al. Validation of the Arab youth mental Health scale as a screening tool for depression/anxiety in Lebanese children. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sawaya H, Atoui M, Hamadeh A, Zeinoun P, Nahas Z. Adaptation and initial validation of the patient Health questionnaire - 9 (PHQ-9) and the generalized anxiety disorder - 7 questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic speaking Lebanese psychiatric outpatient sample. Psychiatry Res. 2016;239:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Senturk V, Stewart R, Sagduyu A. Screening for mental disorders in leprosy patients: comparing the internal consistency and screening properties of HADS and GHQ-12. Lepr Rev. 2007;78(3):231–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Malasi TH, Mirza IA, El-Islam MF. Validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in Arab patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84(4):323–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yazıcı E, Mutu Pek T, Uslu Yuvacı H, Köse E, Cevrioglu S, Yazıcı AB, et al. Perinatal anxiety screening scale validiy and reliability study in Turkish (PASS-TR validity and reliability) Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(4):609–617. doi: 10.1080/24750573.2018.1506247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ibrahim H, Ertl V, Catani C, Ismail AA, Neuner F. The validity of posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1839-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gormez V, Kılınçaslan A, Orengul AC, Ebesutani C, Kaya I, Ceri V, et al. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the revised child anxiety and depression scale – child version in a clinical sample. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(1):84–92. doi: 10.1080/24750573.2017.1297494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hariz N, Bawab S, Atwi M, Tavitian L, Zeinoun P, Khani M, et al. Reliability and validity of the Arabic screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED) in a clinical sample. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(2):222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Başoglu M, Şalcioglu E, Livanou M, Özeren M, Aker T, Kiliç C, Mestçioglu Ö. A study of the validity of a screening instrument for traumatic stress in earthquake survivors in Turkey. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(3):491–509. doi: 10.1023/A:1011156505957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oruc L, Kapetanovic A, Pojskic N, Miley K, Forstbauer S, Mollica RF, Henderson DC. Screening for PTSD and depression in Bosnia and Herzegovina: validating the Harvard trauma questionnaire and the Hopkins symptom checklist. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2008;1(2):105–116. doi: 10.1080/17542860802456620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Zaslavsky AM, Fann JR, Rondon MB, Sánchez SE, Williams MA. Diagnostic validity of the generalized anxiety disorder - 7 (GAD-7) among pregnant women. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.de Lima Osório F, Crippa JA, Loureiro SR. A study of the discriminative validity of a screening tool (MINI-SPIN) for social anxiety disorder applied to Brazilian university students. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(4):239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gelaye B, Zheng Y, Medina-Mora ME, Rondon MB, Sánchez SE, Williams MA. Validity of the posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) checklist in pregnant women. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vossoughi N, Jackson Y, Gusler S, Stone K. Mental Health outcomes for youth living in refugee camps: a review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19(5):528–542. doi: 10.1177/1524838016673602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Cardoso G, Degenhardt L, de Girolamo G, Dinolova RV, Ferry F, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lepine J, Levinson D, Navarro-Mateu F, Pennell B, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Scott KM, Stein DJ, Zaslavsky AM, Koenen KC. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental Health surveys. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(sup5):1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.UNHCR. Global Trends: the world at war. 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].