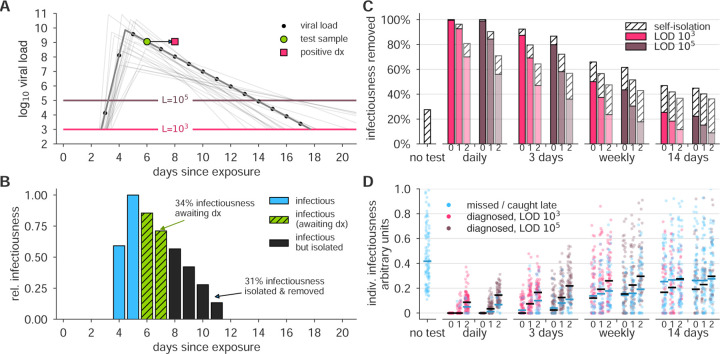

Figure 3: Effectiveness of surveillance testing is compromised by delays in reporting.

(A) An example viral load trajectory is shown with LOD thresholds of two tests, and a hypothetical positive test on day 6, but with results reported on day 8. 20 other stochastically generated viral loads are shown to highlight trajectory diversity (light grey; see Methods). (B) Relative infectiousness for the viral load shown in panel A pre-test (totaling 35%; blue) and post-test but pre-diagnosis (totaling 34%; green), and post-isolation (totaling 31%; black). (C) Surveillance programs using tests at LODs of 103 and 105 at frequencies indicated, and with results returned after 0, 1, or 2 days (indicated by small text beneath bars) were applied to 10, 000 individuals trajectories of whom 35% were symptomatic and self-isolated after peak viral load if they had not been tested and isolated first. Total infectiousness removed during surveillance (colors) and self isolation (hatch) are shown, relative to total infectiousness with no surveillance or self-isolation. Delays substantially impact the fraction of infectiousness removed. (D) The impact of surveillance with delays in returning diagnosis of 0, 1, or 2 days (small text beneath axis) on the infectiousness of 100 individuals is shown for each surveillance program and no testing, as indicated, with each individual colored by test if their infection was detected during infectiousness (medians, black lines) or colored blue if their infection was missed by surveillance or diagnosed positive after their infectious period (medians, blue lines). Units are arbitrary and scaled to the maximum infectiousness of sampled individuals.