Abstract

Nitrogen (N) is one of the most required mineral elements for plant growth, and potassium (K) plays a vital role in nitrogen metabolism, both elements being widely applied as fertilizers in agricultural production. However, the exact relationship between K and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) remains unclear. Apple dwarf rootstock seedlings (M9T337) were used to study the impacts of different K levels on plant growth, nitrogen metabolism, and carbon (C) assimilation in water culture experiments for 2 years. The results showed that both deficiency and excess K inhibited the growth and root development of M9T337 seedlings. When the K supply concentration was 0 mM and 12 mM, the biomass of each organ, root-shoot ratio, root activity and NO3– ion flow rate decreased significantly, net photosynthetic rate (Pn) and photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) being lower. Meanwhile, seedlings treated with 6 mM K+ had higher N and C metabolizing enzyme activities and higher nitrate transporter gene expression levels (NRT1.1; NRT2.1). 13C and 15N labeling results showed that deficiency and excess K could not only reduce 15N absorption and 13C assimilation accumulation of M9T337 seedlings, but also reduced the 15N distribution ratio in leaves and 13C distribution ratio in roots. These results suggest that appropriate K supply (6 mM) was optimal as it enhanced photoassimilate transport from leaves to roots and increased NUE by influencing photosynthesis, C and N metabolizing enzyme activities, nitrate assimilation gene activities, and nitrate transport.

Keywords: M9T337 seedlings, biomass, enzyme activity, NUE, 15N, 13C, nitrate transporter gene expression

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is one of the most abundant elements on the earth and plays an important role in modern agriculture (Chen et al., 2018). N has an irreplaceable role in organ construction, material metabolism, fruit yield, and the quality formation of fruit trees (Warner et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2010; Bai et al., 2016). Sufficient N application not only improves the photosynthetic efficiency of the leaves but also promotes flower bud differentiation (Li et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018), enhances fruit setting rate, and increases yield (Raese et al., 2007). Due to the one-sided pursuit of high yield and large fruits by fruit farmers, the excessive application of N fertilizer in apple orchards has become common in China. The applied N fertilizer dose is are more above the demand of the tree (Ge et al., 2018). Furthermore, the over application of N increases the input cost of farmers, decreases fruit yield and quality (Chen et al., 2017), and directly leads to a decreased N utilization rate. Excessive N also indirectly results in adverse ecological effects, including the increased N deposition, the intensification of the greenhouse effect, soil acidification, and the eutrophication of water bodies (Liu et al., 2013; Zhu and Zhang, 2017). Therefore, it is a main issue for Chinese apple production to promote the efficient utilization of N to improve the quality and yield of apple.

Potassium (K) is the most abundant inorganic cation, and it is important for ensuring optimal plant growth (White and Karley, 2010). K is an activator of dozens of important enzymes, such as protein synthesis, sugar transport, N and C metabolism, and photosynthesis. It plays an important role in the formation of yield and quality improvement (Marschner, 2012; Oosterhuis et al., 2014). K is also very important for cell growth, which is an important process for the function and development of plants (Hepler et al., 2001). In terms of the growth-promoting mechanism of K, it is generally agreed that K stimulates and controls ATPase in the plasma membrane to generate acid stimulation, which then triggers cell wall loosening and hydrolase activation (Oosterhuis et al., 2014), thus promoting cell growth. K has strong mobility in plants and plays an important role in regulating cell osmotic pressure and balancing the cations and anions in the cytoplasm (Kaiser, 1982; Hu et al., 2016a). Through these processes, K is involved in the regulation of stomatal opening and closing, cell elongation, and other important physiological processes. There are many studies on the effect of K level on plant growth. Jin et al. (2007) found that the highest yield and fruit quality were obtained in Red Fuji apple under treatment with 600 kg/ha K; Wang et al. (2017) determined that 6 mM K treatment promoted pear growth and improved photosynthetic efficiency; and Lu et al. (2001) also reported increased production with better fruit quality parameters in navel orange supplied under 500 kg/ha K. There is an interaction between K and other nutrient ions. High K concentrations in the soil solution inhibit Mg uptake and may induce Mg deficiency in plants (Tränkner et al., 2018). However, K deficiency could promote the absorption of Na+ and Ca2+ in maize (Du et al., 2017), and could inhibit N absorption in cotton and significantly reduce the content of NO3– in the leaves (Hu et al., 2017). It is evident that K affects significantly the absorption and utilization of other nutrients by plants, and the appropriate K level differs in different crops.

Among the interactions between K and other nutrients, the interaction with N is the most important. Some studies evaluated the relationship between K and N metabolism. In contrast to the antagonistic relationship between K+ and NH4+ nutrition, the acquisition rates of K+ and NO3– are often found to be positively correlated (Rufty et al., 1981; Coskun et al., 2016), and sufficient K supply can promote N metabolism and enhance the synthesis of amino acids and proteins (Ruan et al., 1998; Ruiz and Romero, 2002). Hu et al. (2016b) found that K deficiency could reduce Nitrate reductase (NR), Glutamine synthetase (GS), and Glutamate synthase (GOGAT) activities and inhibit nitrate absorption in cotton, whereas Armengaud et al. (2009) found that K deficiency could up-regulate the activities of GS and Glu dehydrogenase (GDH) in Arabidopsis. Metabolism of N affected by K appears to vary in different types of plants. Meanwhile, the level of K has a significant impact on C metabolism, and also a strong interaction exists between C metabolism and N metabolism in the metabolic process and energy level (Hu et al., 2017). Based on previous studies, we further evaluated the effects of different K levels on photosynthesis, C metabolism, nitrate uptake, utilization and distribution of M9T337 seedlings through non-invasive micro-measurement technology, 15N, 13C isotope labeling, and fluorescence quantitative PCR technology. Our studies provided strong evidence for the direct or indirect impact of K level on N absorption and utilization. These experimental results will provide a scientific basis toward the amelioration of problems, related to the poor growth and low N utilization rate of M9T337 seedlings caused by unreasonable K application.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Treatments

The experiment was conducted in 2018 and 2019. M9T337 seedlings, an apple dwarf rootstock, were used in current study. M9T337 seedlings (n = 200) were grown under natural light, 22–28°C (day) and 5–10°C (night), and a relative humidity (RH) of 55–65%. Seedlings with eight true leaves and about 15 cm height (about 60 days old) were planted on foam plates with eight holes in each plate. Single seedling was planted in each hole. Six liters of nutrient solution was added to each basin (plate). The seedlings were cultured with 1/2 Hoagland’s (Hoagland and Arnon, 1950) nutrient solution for 7 days to gradually adapt to the nutrient solution, following which they were transferred to full-concentration Hoagland’s nutrient solution. After 30 days of treatment, the NO3– ion velocity of the root system was measured, and the root morphology, root activity, biomass of each organ, and K content were measured.

The trial began on April 9 (10 days after planted), with K2SO4 as the only K source. Five K supply levels (0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 mM) were applied with 16 repetitions, respectively. The specific concentrations of the other nutrients were as follows: 4 mM Ca(NO3)2, 1 mM Ca(15NO3)2 [Ca(15NO3)2, produced by the Shanghai Institute of Chemical Technology, with abundances of 10.14%, for 15N marking], 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM EDTA-Fe, 37 μM H3BO4, 9 μM MnCl2 ⋅ 4H2O, 0.3 μM CuSO4 ⋅ 5H2O, and 0.76 μM ZnSO4 ⋅ 7H2O. The pH of the nutrient solution was adjusted to 6.0 ± 0.1 with H3PO4 or NaOH. The test processing time was 30 days. Samples were taken at 9:00–10:00 a.m. on the 10th, 20th, and 30th day of treatment for enzyme activity and nitrate transporter gene determination. After 30 days of treatment, the NO3– ion velocity of the root system was measured, and the root morphology, root activity, biomass of each organ, K content, and 15N abundance were measured.

13C Labeling of Seedlings and Isotope Analysis

After 27 days of treatment, 13C isotope labeling was performed. Ba13CO3 (13C independence is 98%) was used as a selection marker, and the dosage was 0.2 g. The seedlings were placed together with the markers, fans, and reduced iron powder into a sealed marking room to make transparent film. The transmittance of sunlight in the labeling chamber was 95% of the natural light intensity. Labeling work started at 9:00 a.m., at which point the fan was turned on and the labeling chamber was sealed. One milliliter of hydrochloric acid (1 mol/L) was injected into the beaker with a syringe every 0.5 h in order to maintain the concentration of CO2, and the 13C labeling lasted for 4 h. In order to keep low temperature during the labeling process, an appropriate amount of ice was added to the bottom of the labeling chamber to limit the temperature within the range of 28–37°C. At the same time, three other plants were selected as the control (13C natural abundance), and destructive samples were taken on the third day after labeling and 13C was determined.

Biomass samples for 13C and 15N analyses were collected at the end of the labeling for 13C and 15N analyses. The samples were dried and then ground with an electric grinder and filtered with a 0.25 mm mesh screen. The abundance of 15N and 13C were measured with a ZHT-03 mass spectrometer from the Beijing Analytical Instrument Factory (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences). Three replicates were conducted for each treatment. The formula is calculated according to Wang et al. (2020).

Calculation of 15N

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Ndff is the contribution rate of plant organ to total nitrogen from fertilizer of 15N

Calculation of 13C

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Dry Matter Weight and K Content of Plant

After 30 days of treatment, the seedlings were divided into roots, stems, and leaves. The samples were washed in an order of tap water, detergent, deionized water, and 1% hydrochloric acid, and were then washed with deionized water for three times. The samples were dried at 105°C for 30 min, followed by 80°C for 3 days. The dry weight was recorded as the biomass. K content was measured according to Hu et al. (2017) using atomic absorption techniques. Three replicates were conducted for each treatment.

Root Morphology and Root Activity

For each treatment group, three M9T337 seedlings were randomly sampled and rinsed with deionized water before analysis. The root images were analyzed with WinRhizo software (Regent Instruments Canada Inc). Total root length and total root surface area were calculated for each treatment.

Root activity was measured using the triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) method described by Chen et al. (2018).

Photosynthetic Parameters and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

After 30 days of treatment, the fourth main-stem leaf from the terminal of the plant were selected for measurement of photosynthetic parameters (Pn, net photosynthetic rate; Gs, stomatal conductance; Ci, intercellular CO2 concentration). Every leaf was measured three times between 9:00 and 11:30 AM with a LI-6400XT portable photo synthesis system (LI-Cor, Lincoln, NE, United States).

During the same period, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were estimated using a pulse modulated chlorophyll fluorescence meter (PAM 2500, Walz, Germany) on the same leaf. Every leaf was measured three times. The maximum photochemical quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) was measured after a 25 min period of dark adaptation. Non-photochemical quenching (qN), coefficient of photochemical quenching (qP), and electron transport rate (ETR) were recorded after measuring light-adapted leaves.

NO3– Ion Flow Rate in Roots

The NO3– dynamic flow rate in roots was measured using a non-damaging micro-measurement system (NMT 100 Series, United States) at Shandong Agricultural University. The root system of M9T337 seedlings was washed with ultrapure water, and then the roots 1–2 cm away from the root tip were placed in a plastic dish with a filter paper strip, and the filter paper strip was fixed with a small glass block. The test solution [0.25 mM KNO3, 0.625 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.25 mM Ca(NO3)2, pH 6.0] was added until the root was submerged. This was left to stabilize for 10 min, following which the test was started after the NO3– flow rate on the root surface was stable. According to the measurement, the NO3– ion flow velocity of seedlings from the different treatments was the largest in the dense root hair area about 8 mm from the root tip. Thus, each sample was randomly selected for a repeated test, and the data were collected at three points, where each treatment detected six samples, and each sample was stable for 10 min. After the test, MageFlux (imFluxes V2.0), a data analysis software provided by Xuyue company, was used for analysis. If the flow velocity J is positive, it indicates ion outflow, and if the flow velocity is negative, it indicates ion inflow.

NR, GS, Rubisco, SPS and SS Activities

The NR (EC 1.6.6.1) and GS (EC 6.3.1.2) activities were measured according to the modified method described by Hu et al. (2016b). The supernatant was used for the measurement of light absorption at 540 nm, the NR activity was calculated from the nitrite N standard curve, and the GS activity was calculated from the standard curve of c-glutamyl hydroxamate.

The Rubisco (EC 4.1.1.39), SPS (EC 2.4.1.14), and SS (EC 2.4.1.13) activities were extracted according to Hu et al. (2016a). Three replicates were conducted for each treatment.

RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis

After 30 days of treatment, 0.1 g root was quickly ground into powder in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA integrity was detected by electrophoresis, and RNA purity was determined by a nucleic acid analyzer. The cDNA was reverse-transcribed using a 5 × all-in-one RT Master Mix (ABM, Canada) kit. According to the NRT1.1 and NRT2.1 gene sequence of the apple database,1 gene-specific primers were developed using Primer 3.0 (Table 1) based on the cDNA template. The Actin gene was used as a reference in accordance with the EvaGreen Express 2 × qPCR Master Mix (ABM, Canada) kit steps. the Real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR amplification was used to assess gene transcription. The reaction procedure was as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C, 30 s; denaturation at 95°C for 5 s, annealing at 60–65°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 20–30 s, 45 cycles. All PCR reactions were performed with three biological and three technical replicates. The 2–ΔΔCT method was used for analyzing the real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR amplification data.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences for qRT-PCR.

| Gene name | Forward sequence of the primers (5′→3′) | Reverse sequence of the primers (5′→3′) |

| MdNRT1.1 | CTCGGCCTCATTGTGTTCTT | TCCAACGGCAGTTCCATATTC |

| MdNRT2.1 | GCTGTACTCTTCCTGTGACTTT | CGTCGACTTCTCGACATCTTT |

| Actin | TGGTGTCATGGTTGGTATGG | CCGTGCTCAATGGGATACTT |

Statistical Analysis

Origin 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, United States) was used to prepare the figures. Data were analyzed with SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) using one-way factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA). In all cases, differences were considered significant at a probability level of P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Changes of Total Dry Matter, Root-Shoot Ratio and Root Activity

The biomass of each organ and the root-shoot ratio of M9T337 seedlings differed significantly under different K levels. As shown in Table 2, the biomass of seedlings was inhibited by low and high K treatments, and the highest was related to K6 treatment. With an increase in K supply, the root-shoot ratio initially increased and then decreased, and maximized under 6 mM K treatment, indicating that K deficiency and excessive K has a significant impact on root growth than that on aboveground parts of seedlings.

TABLE 2.

Plant biomass and root/shoot ratio of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019.

| Treatment | 2018 |

2019 |

||||

| Shoot dry weight (g/plant) | Root dry weight (g) | Root-shoot ratio | Shoot dry weight (g/plant) | Root dry weight (g) | Root-shoot ratio | |

| K0 | 3.45 ± 0.25c | 1.27 ± 0.08d | 0.37 ± 0.01b | 3.93 ± 0.14d | 1.45 ± 0.08d | 0.37 ± 0.03c |

| K3 | 4.03 ± 0.07bc | 1.59 ± 0.08c | 0.40 ± 0.02ab | 4.30 ± 0.16c | 1.77 ± 0.09c | 0.41 ± 0.03ab |

| K6 | 5.07 ± 0.58a | 2.17 ± 0.13a | 0.43 ± 0.03a | 5.37 ± 0.15a | 2.30 ± 0.13a | 0.43 ± 0.01a |

| K9 | 4.40 ± 0.21b | 1.86 ± 0.12b | 0.42 ± 0.01a | 4.84 ± 0.15b | 1.94 ± 0.07b | 0.40 ± 0.00ab |

| K12 | 3.69 ± 0.98c | 1.40 ± 0.08d | 0.38 ± 0.02b | 4.34 ± 0.27c | 1.66 ± 0.10c | 0.38 ± 0.01bc |

Each treatment had three biological replicates and values are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD, N = 3). Different letters denote significant differences (P < 0.05).

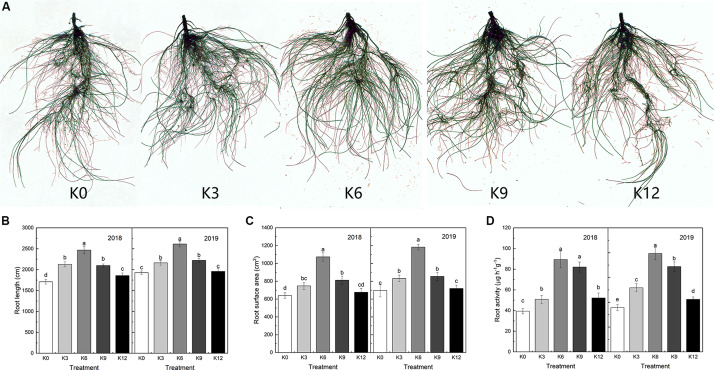

The root morphology of M9T337 seedlings was also significantly affected by different K levels (Figure 1A). In 2018 and 2019, the root length and total root surface area of seedlings were the largest under 6 mM K concentration, and the root length and surface area of seedlings under 0 mM and 12 mM K treatment were significantly lower than those of the 6 mM treatment. The result showed that low and high K supply levels inhibited the elongation and growth of root (Figures 1B,C).

FIGURE 1.

Root morphology (A), root length (B), root surface (C), and root activity (D) of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. Each treatment had three biological replicates and the assays were repeated three times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD (N = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

As shown in Figure 1D, K levels also significantly affected root activity. The highest root activity appeared in 6 mM K treatment, and inappropriate K levels had a negative effect on root activity.

Changes of K Accumulation in Various Organs of M9T337 Seedlings

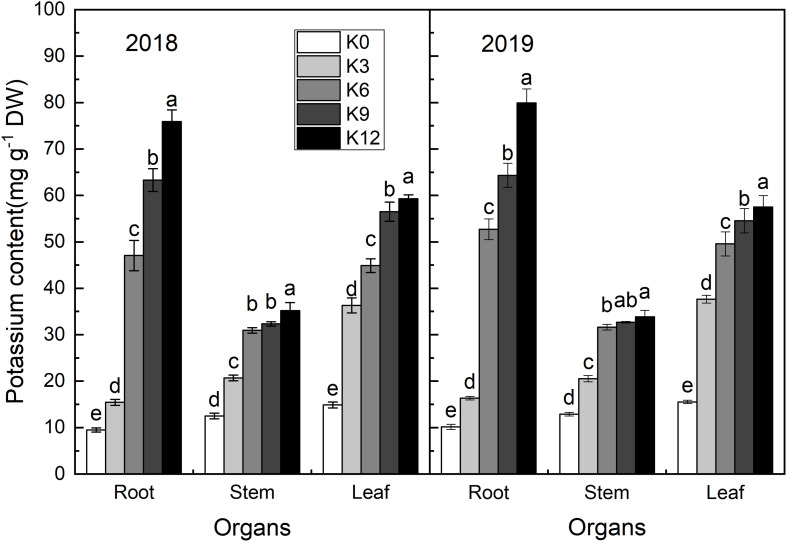

Potassium content in the roots, stems, and leaves of seedlings increased with the increasing in K supply (Figure 2). The K content of all organs was the highest under K12 treatment. In K0 and K3 treatments, the K content of each organ was the highest in leaves, second-highest in the stems, and lowest in roots. Under the other K level treatments, the K content of each organ was highest in the roots and lowest in the stems. So, K was preferentially supplied to the shoot under low K conditions.

FIGURE 2.

K concentrations (mg g–1 DW) in the leaves, stems, and roots of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. Each treatment had three biological replicates and the assays were repeated three times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD (N = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

Changes of Photosynthesis and Chlorophyll Fluorescence

We monitored photosynthetic rate and gas exchange parameters to determine possible effects of different K levels. With increasing K supply, Pn and Gs increased first and then decreased (Table 3), reaching the maximum value in K6 treatment. However, Ci was the highest in K0 treatment and the lowest in K6 treatment.

TABLE 3.

Photosynthetic Parameters and chlorophyll fluorescence of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019.

| Year | Treatment | Pn [μmol(CO2) ⋅ m–2 ⋅ s–1)] | Gs [μmol(H2O) ⋅ m–2 ⋅ s–1] | Ci (μmol ⋅ mol–1) | Fv/Fm | ETR | qP | qN |

| 2018 | K0 | 9.6 ± 0.3d | 121 ± 8d | 262 ± 7a | 0.773 ± 0.013c | 145 ± 8d | 0.733 ± 0.008d | 0.953 ± 0.031a |

| K3 | 11.3 ± 0.4bc | 151 ± 7b | 223 ± 7b | 0.818 ± 0.015b | 158 ± 4c | 0.755 ± 0.012c | 0.909 ± 0.014b | |

| K6 | 14.5 ± 0.5a | 166 ± 9a | 207 ± 10c | 0.839 ± 0.009a | 198 ± 11a | 0.835 ± 0.018a | 0.812 ± 0.010d | |

| K9 | 12.0 ± 0.4b | 145 ± 5b | 219 ± 8b | 0.821 ± 0.013b | 187 ± 8b | 0.804 ± 0.012b | 0.819 ± 0.021d | |

| K12 | 10.6 ± 0.4c | 135 ± 5c | 213 ± 9c | 0.816 ± 0.011b | 183 ± 12b | 0.798 ± 0.010b | 0.863 ± 0.008c | |

| 2019 | K0 | 9.0 ± 1.4d | 113 ± 6d | 267 ± 10a | 0.751 ± 0.014c | 134 ± 10d | 0.691 ± 0.022d | 0.934 ± 0.022a |

| K3 | 12.2 ± 0.4b | 154 ± 9bc | 237 ± 9b | 0.815 ± 0.017b | 179 ± 5c | 0.783 ± 0.042b | 0.887 ± 0.025b | |

| K6 | 16.3 ± 0.7a | 188 ± 6a | 203 ± 4d | 0.841 ± 0.006a | 211 ± 10a | 0.857 ± 0.021a | 0.784 ± 0.014d | |

| K9 | 12.4 ± 0.6b | 164 ± 9b | 225 ± 3c | 0.825 ± 0.008b | 193 ± 11b | 0.797 ± 0.031b | 0.807 ± 0.021c | |

| K12 | 10.4 ± 0.3c | 148 ± 7c | 204 ± 7d | 0.809 ± 0.011b | 178 ± 7c | 0.742 ± 0.018c | 0.865 ± 0.008b |

Each treatment had three biological replicates and values are expressed as means ± SD (N = 3). Different letters denote significant differences (P < 0.05).

Chlorophyll fluorescence was further investigated to understand the internal causes of the effects of different K levels on photosynthesis. The K6 seedlings had a significantly higher Fv/Fm, ETR and qP, and the qN was the lowest (Table 3). This indicates that unsuitable K levels can inhibit photosynthetic electron transfer, increase heat dissipation and even damage the light system (K0 treatment).

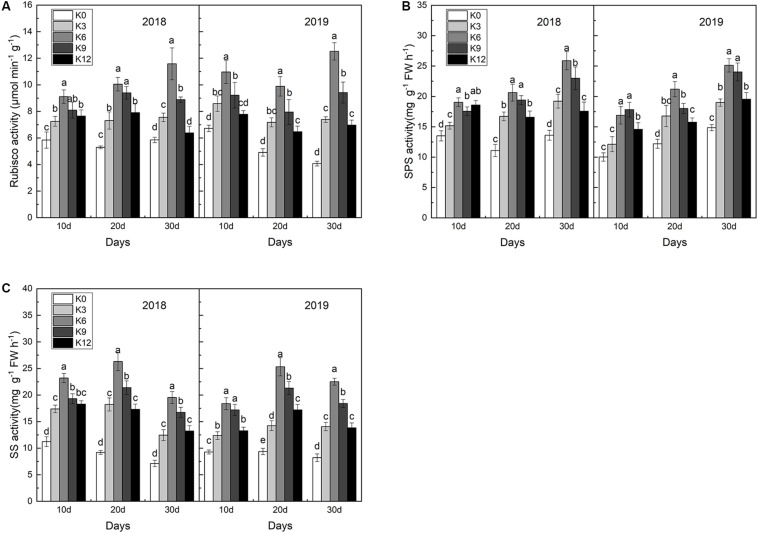

Changes of Rubisco, SPS and SS Activities

In order to explore the effect of K supply on C metabolizing enzymes, we measured the activities of Rubisco, SPS and SS in leaves. As shown in Figure 3, after 30 days, seedlings subjected to K6 treatments acquired the highest activities of Rubisco, SPS and SS, followed by K9 treatments, and K0 treatments obtained the lowest activities. These results indicate that low or high K levels can significantly inhibit the activity of C metabolizing enzymes in leaves, and the inhibition effect is more significant under low K levels than that under high K levels.

FIGURE 3.

Rubisco (A), SPS (B), and SS (C) activities in the leaves of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. Each treatment had three biological replicates and the assays were repeated three times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD (N = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

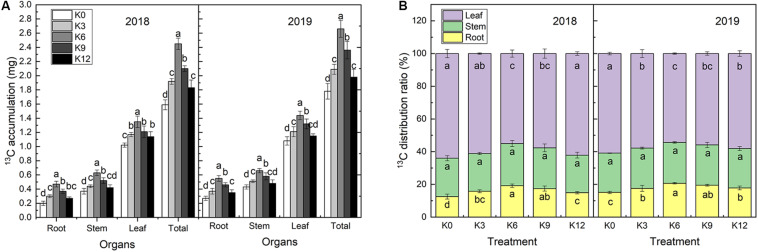

Changes of 13C Accumulation and Distribution

13C isotope labeling results showed that 13C accumulation in M9T337 seedlings significantly varied under different levels of K supply (Figure 4). The 13C accumulation rate in all organs of seedlings under the K6 treatment were significantly higher than those under of other treatments (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

13C accumulation (A) and 13C distribution ratio (B) of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. Each treatment had three biological replicates and the assays were repeated three times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD (N = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

The distribution ratio of 13C to each organ is related to its competitive ability but also chiefly to its transport capacity within the plant. The 13C distribution rates for each treatment were consistent in both years, among which the leaves had the highest values followed by the stems, and roots (Figure 4B). K supply increased the 13C distribution rate in roots, which increased first and then decreased with increasing K levels. The 13C distribution rate in roots treated with 6 mM K+ was the highest and increased by 52.65% and 36.58% compared with the K0 treatment in 2018 and 2019, respectively. An different trend was, however, observed for leaves. No significant effect was observed on the 13C distribution ratio in stems under K treatments.

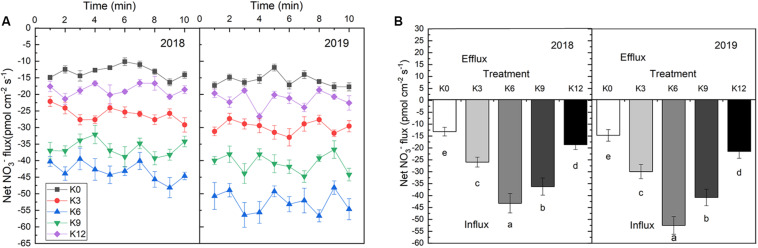

Changes of NO3– Ion Flow Rate in Roots

The NO3– ion flow velocity in roots increased at first as K supply rose, but then decreased, which implied that a moderate K supply level will promote nitrate ions to be take up by roots (Figure 5). In 2018 and 2019, the average NO3– flux rates within 10 min of seedling root exposure to K6 treatment increased by 229.3% and 132.1%, 256.7%, and 144.7%, respectively, compared with those under K0 and K12 treatments.

FIGURE 5.

NO3– ion flow rate in root of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. (A) Net NO3– fluxes in the root of apple seedlings for 10 min. (B) Mean rate of NO3– fluxes during the entire 10 min. Data are means ± SD (N = 6). min = minutes. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

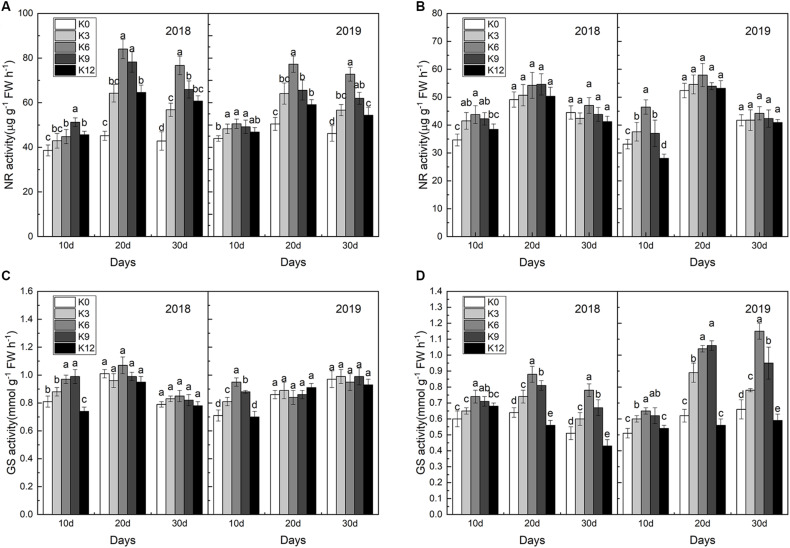

Changes of Nitrogen-Metabolizing Enzymes Activities

Compared with roots, NR activities in leaves were significantly affected by K levels (Figure 6), and NR activities in leaves under the K6 treatment were significantly higher than the other treatments for all three stages (Figure 6A), which improved nitrate assimilation capacity. In contrast, NR activities in the leaves under the K0 and K12 treatments were relatively lower. Unlike NR activities, differences in GS activities in roots was greater between different K treatments than that in leaves (Figures 6C,D), and the higher values appeared in the K6 treatment.

FIGURE 6.

NR activities in the leaves (A) and roots (B); GS activities in the leaves (C), and roots (D) of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. Each treatment had three biological replicates and the assays were repeated three times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD (N = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

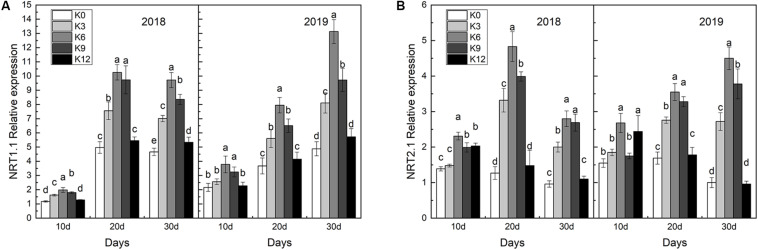

Changes of Expression of NRT1.1 and NRT2.1 in Roots

We compared the effects of the different K supply levels on NRT1.1 and NRT2.1 gene expressions and discovered that their expressions were affected by K applications (Figure 7). As expected, we found that NRT1.1 and NRT2.1 gene expressions in roots were significantly higher under the K6 treatment compared to the control (K0) and the excessive K supply treatment (K12), which suggested that K can induce the nitrate-responsive pathway for NRT gene family expression in M9T337 seedlings.

FIGURE 7.

NRT1.1 gene expressions (A) and NRT2.1 gene expressions (B) in the roots of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. Each treatment had three biological replicates and the assays were repeated three times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD (N = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

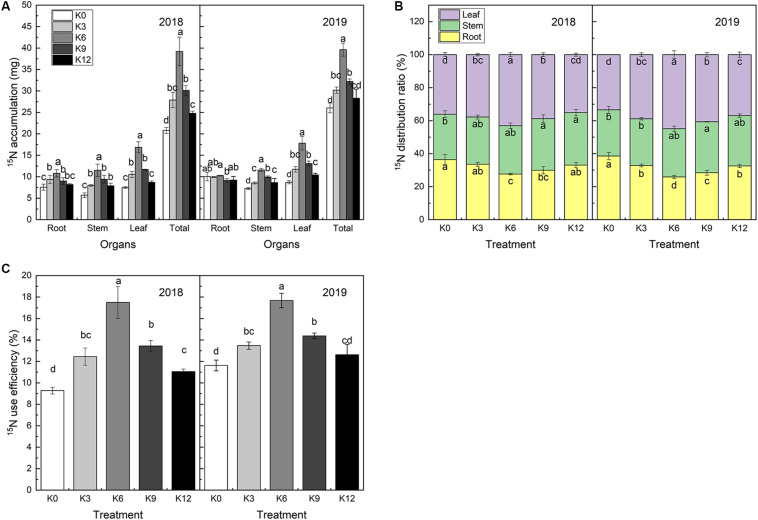

Changes of 15N Absorption, Distribution, and Use Efficiency

15N isotope labeling results showed that there were significant differences in 15N absorption and 15N use efficiency of M9T337 seedlings under different K levels (Figures 8A,C). After 30 days of treatment, the 15N absorption rate of seedlings in K6 treatment was significantly higher than that of the other treatments, and the 2-year average was 1.70 and 1.49 times higher than that of K0 and K12 treatments, respectively.

FIGURE 8.

15N accumulation (A), 15N distribution ratio (B) and 15NUE (C) of M9T337 seedlings treated with K0 (0 mM K+), K3 (3 mM K+), K6 (6 mM K+), K9 (9 mM K+), or K12 (12 mM K+) in 2018 and 2019. Each treatment had three biological replicates and the assays were repeated three times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD (N = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

The 15N use efficiency was calculated from the 15N absorption content divided by the total 15N application rate. As expected, 15N use efficiency was highest in K6 treatment and lowest in K0 treatment (Figure 8C). This declared that the allocation of NO3– to the roots/leaves might be responsible for the difference in 15N use efficiency among the different K supply levels treatments.

Discussion

Effects of K Levels on Root Growth and 13C Assimilation and Distribution of M9T337 Seedlings

Potassium has a significant effect on the growth and development of plant roots. Jung et al. (2009) found that in Arabidopsis thaliana, root hair elongation could be promoted in a K-deficient environment after 28 h. Høgh-Jensen and Pedersen (2003) and Jilani (2008) discovered that pea (Pisum sativum), barley (Hordeum vulgare), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), rye (Secale cereale), and red clover (Trifolium pratense) could modify their root hair length in response to low K conditions. Therefore, plants can cope with short-term K deficiency by promoting root growth. However, compared with the lack of N and phosphorus, the growth of plant roots is strongly inhibited under conditions of prolonged K deficiency, and the root-shoot ratio will be significantly reduced (Hermans et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2015). We also found that moderate K concentrations (6 mM K+) can promote root growth. However, root growth was significantly inhibited by unsuitable K supply levels, which may be due to an increase in ethylene and a decrease in indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in the roots (Zhang et al., 2009). At the same time, the limited transport of photosynthetic products from leaves to roots may also explain why unreasonable K supply hinders root growth (Figure 4B).

The percentage of 15N in each organ accounting for the total 15N content reflects the distribution of N fertilizer in the seedlings and the migration regularity in the organs. 15N distribution ratio in roots was found higher in K0 and K12 treatments, while the lowest in K6 treatment. And, the opposite trend exhibited in the leaves (Figure 8B). This suggested that the K level can affect root-to-leaf transportation.

Potassium status of plants has a significant effect on the transport and distribution of photosynthetic products (Pettigrew, 2008). Sufficient K supply can establish osmotic potential in the phloem and help to transfer photosynthates from source to sink organs (Cakmak, 2005). However, the loading of photosynthates in phloem of K deficient plants is inhibited and the transport to roots is significantly reduced (Gerardeaux et al., 2010). In this study, the 13C isotope labeling results showed that the 13C assimilation rate and distribution ratio in roots were higher under an appropriate K supply level. This indicates that insufficient or excessive K supply can inhibit the C assimilation of leaves and the photosynthetic products transport from leaves to roots. Correlation analysis also showed that the 13C distribution ratio was positively correlated with root biomass. Meanwhile, the 13C distribution ratio of roots was significantly positive related to photosynthesis and C metabolizing enzyme activity (SS and SPS activities). We also measured the gas exchange parameters of leaves, and found that the Pn and Gs of seedling decreased significantly under the treatment of low and high K supply, which indicates that inappropriate K supply would limit photosynthesis through stomatal restrictions. Ci increased significantly under K0 treatment, therefore, the decrease of Pn may also be related to limitations of the optical system. Furthermore, we found that Fv/Fm, qP and ETR of leaves under insufficient or excessive K supply were significantly lower than those of the 6 mM K treatments. These results clearly show that K deficiency or excess can inhibit the photochemical efficiency and electron transfer efficiency of PSII reaction center. Lu et al. (2016) also found similar results on oilseed rape. In conclusion, we showed that K affected C assimilation and distribution by regulating photosynthesis and C metabolizing enzymes. The increase in the distribution of photosynthetic products to the root system will promote growth and development of the root system, then improving the absorption ability of N, thus increasing NUE.

Effect of K Levels on Nitrate Metabolism of M9T337 Seedlings

Previous research has indicated that a close relationship exists between K+ and root-induced NO3– uptake (Dong et al., 2004). Parker and Newstead (2014) showed that NRT1.1 can take up nitrate using two distinct affinity modes. Li et al. (2007) and Munos et al. (2004) demonstrated that NRT2.1 is a high-affinity transporter for nitrate. We tested the responses of M9T337 seedlings to different concentrations of K and found that 6 mM K+ induced the greatest increase in NRT1.1 and NRT2.1 expressions, which led to a higher nitrate absorption capacity. Meanwhile, a higher net NO3– influx rate under 6 mM K+ treatment also implied that a moderate K supply level will promote nitrate ions into roots (Figure 5). In addition, an ideal root morphology and activity were important for nutrient absorption (Sattelmacher et al., 1994). Our results also found that M9T337 seedlings treated with 6 mM K+ had larger root surface area and higher root activity. As a result, a higher 15N absorption content appeared under appropriate K supply conditions (Figure 8). In addition, K also affected the distribution of NO3– between root and shoot (Ruiz and Romero, 2002). Our results show that higher 15N distribution ratio in roots were found in K deficient or excess treatments, while the highest 15N distribution ratio in leaves appeared under appropriate K supply treatments. This suggests that appropriate K supply not only increases NO3– absorption in roots, but also promotes the transport from roots to shoots. Rufty et al. (1981) and Wang et al. (2003) also reported that K deficiency can seriously hinder the assimilation and translocation of nitrate, and higher N assimilation occurs in the roots. So it is necessary to focus on the effect of K on N assimilation in roots and leaves.

Nitrate reductase is the key enzyme for regulating the rate limiting step of the NO3– assimilation pathway (Kovács et al., 2015; Ren et al., 2017; Teng et al., 2017). NO3– will be transformed into NH4+ in plants, and NH4+ will be converted mainly through the GS/GOGAT pathway. Thus the activity of NR and GS will affect the absorption and assimilation of N. The inhibition of K deficiency on NR activity has been verified in cotton, cucumber, and Arabidopsis (Ruiz and Romero, 2002; Balkos et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2016b). Generally, with high external K+ supply, the co-translocation of K+ and NO3– to the shoot increases (Ben Zioni et al., 1971; Blevins et al., 1978), and both storage of NO3– and NR activity increases in leaves, while less N assimilation is found in roots (Blevins et al., 1978; Rufty et al., 1981). Consistent with previous results, we also found that for a certain range, with the increase of K supply, GS activity of roots and NR activity of leaves of M9T337 seedlings gradually increased, which promoted the assimilation of NO3–. However, when the K supply is too high, the activity of these enzymes will decrease, which may be related to the inhibition of photosynthesis and the reduction of energy supply.

The absorption and distribution of nitrate also depends on the energy and C skeleton from photosynthesis (Liu et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2019). We found that the higher NUE was related to the improvement of the fixation rate of photosynthetic carbon and the efficiency of photosynthetic electron transfer under the appropriate K supply level. In addition, the results of 15N labeling showed that low or high K levels were not conducive to NO3– transport from root to leaf, which was consistent with previous studies (Ruiz and Romero, 2002; Coskun et al., 2016). Han et al. (2016) found that the increased distribution of NO3– to the aboveground parts will enable crops to fully utilize sunlight energy to carry out NO3– metabolism and energy conversion, so as to improve the NUE of crops. Perchlik and Tegeder (2018) also reported that increasing N allocation to leaves represents an effective strategy for improving C fixation and photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency (NUE).

Consequently, the M9T337 seedlings treated with 6 mM K+ showed better growth, improved photosynthate production and NUE. Our findings reveal how the application of K affects the uptake, transport, and assimilation of NO3–, and deepens our understanding of the relationship between K supply and improved NUE. It should be noted that our research was mainly focused on physiological mechanisms on K induces positive changes in N metabolism in M9T337 seedlings. Further molecular studies are needed to gain a deeper understanding of how K improves NUE.

Conclusion

Our results showed that M9T337 seedlings treated with the optimum K levels had (i) enhanced 13C accumulation and 13C transport from leaves to roots; (ii) increased root NO3– ion flow rate; (iii) relatively high N metabolic enzyme activities; (iv) up-regulated transcript levels of nitrate uptake genes (NRT1.1; NRT2.1); (v) enhanced 15N translocation from roots to leaves; (vi) higher 15NUE. In conclusion, optimum K levels can increase NUE by affecting root morphology and activity, the activity of enzymes involved in C and N metabolism, nitrate uptake genes, and nitrate transport.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

YJ, SG, and XX conceived and designed the experiments. XX, XD, FW, JS, QC, GT, and ZZ performed all the experiments. XX, ZZ, and SG analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Xin Hou, Zhihang Jia, Bingyu Li, Xin Zhang, Yue Xing, Zhaoxia Liu, and other students for helping us perform the study.

Funding. This work was supported by the Special Fund for the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0201100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31501713), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-27), and Taishan Scholar Assistance Program from Shandong Provincial Government.

References

- Armengaud P., Sulpice R., Miller A. J., Stitt M., Amtmann A., Gibon Y. (2009). Multilevel analysis of primary metabolism provides new insights into the role of potassium nutrition for glycolysis and nitrogen assimilation in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 150 772–785. 10.1104/pp.108.133629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L. Q., Deng H. H., Zhang X. C., Yu X. C., Li Y. S. (2016). Gibberellin is involved in inhibition of Cucumber growth and nitrogen uptake at Suboptimal root-Zone temperatures. PLoS One 11:e0156188. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkos K. D., Britto D. T., Kronzucker H. J. (2010). Optimization of ammonium acquisition and metabolism by potassium in rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. IR-72). Plant Cell Environ. 33 23–34. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Zioni A., Vaadia Y., Herman L. S. (1971). Nitrate uptake by roots as regulated by nitrate reduction products of the shoot. Physiol. Plantarum. 24 288–290. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1971.tb03493.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins D. G., Barnett N. M., Frost W. B. (1978). Role of potassium and malate in nitrate uptake and translocation by wheat seedlings. Plant Physiol. 62 784–788. 10.1104/pp.62.5.784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I. (2005). The role of potassium in alleviating detrimental effects of abiotic stresses in plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 168 521–530. 10.1002/jpln.200420485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Feng H., Hu Q., Qu H., Chen A., Xu G., et al. (2015). Improving rice tolerance to potassium deficiency by enhancing OsHAK16p: WOX11-controlled root development. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13 833–848. 10.1111/pbi.12320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. D., Wang L., Fabrice M. R., Tian Y. N., Qi K. J., Tao S. T., et al. (2018). Physiological and nutritional responses of pear seedlings to nitrate concentrations. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1679. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Ding N., Peng L., Ge S. F., Jiang Y. M. (2017). Effects of different nitrogen application rates on 15 N-urea absorption, utilization, loss and fruit yield and quality of dwarf apple. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 28 2247–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun D., Britto D. T., Kronzucker H. J. (2016). The nitrogen–potassium intersection: membranes, metabolism, and mechanism. Plant Cell Environ. 10 2029–2041. 10.1111/pce.12671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Tang W., Li Z., Zhang D. (2004). On potassium deficiency in cottone disorder, cause and tissue diagnosis. Agric. Conspect. Sci. 69 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Du Q., Zhao X. H., Jiang C. J., Wang X. G., Han Y., Wang J., et al. (2017). Effect of potassium deficiency on root growth and nutrient uptake in maize (Zea mays L.). Agric. Sci. 8 1263–1277. 10.4236/as.2017.811091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S. F., Zhu Z. L., Peng L., Chen Q., Jiang Y. M. (2018). Soil nutrient status and leaf nutrient diagnosis in the main apple producing regions in China. Hortic. Plant J. 4 89–93. 10.1016/j.hpj.2018.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerardeaux E., Jordan-Meille L., Constantin J., Pellerin S., Dingkuhn M. (2010). Changes in plant morphology and dry matter partitioning caused by potassium deficiency in Gossypium hirsutum (L.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 67 451–459. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. L., Song H. X., Liao Q., Yu Y., Jian S. F., Lepo J. E., et al. (2016). Nitrogen use efficiency is mediated by vacuolar nitrate sequestration capacity in roots of Brassica napus. Plant Physiol. 170 1684–1698. 10.1104/pp.15.01377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler P. K., Vidali L., Cheung A. Y. (2001). Polarized cell growth in higher plants. Annu.Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 17 159–187. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans C., Hammond J. P., White P. J., Verbruggen N. (2006). How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci. 11 610–617. 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland D. R., Arnon D. I. (1950). The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Calif. Agric. Exp. Station Circ. 347 1–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)73482-9 29777460 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Høgh-Jensen H., Pedersen M. B. (2003). Morphological plasticity by crop plants and their potassium use efficiency. J. Plant Nutr. 26 969–984. 10.1081/pln-120020069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Coomer T. D., Loka D. A., Oosterhuis D. M., Zhou Z. (2017). Potassium deficiency affects the carbon-nitrogen balance in cotton leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 115 408–417. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Jiang N., Yang J., Meng Y., Wang Y., Chen B., et al. (2016a). Potassium (K) supply affects K accumulation and photosynthetic physiology in two cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) cultivars with different K sensitivities. Field Crop. Res. 196 51–63. 10.1016/j.fcr.2016.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Zhao W., Yang J., Oosterhuis D. M., Loka D. A., Zhou Z. (2016b). Relationship between potassium fertilization and nitrogen metabolism in the leaf subtending the cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) boll during the boll development stage. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 101 113–123. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilani G. (2008). Differential response of root morphology to potassium deficient stress among rice genotypes varying in potassium efficiency. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 5 79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H. C., Zhang L. S., Li B. Z., Han M. Y., Liu X. G. (2007). Effect of potassium on the leaf nutrition and quality of Red Fuji apple. Acta Agric. Bor Occid. Sin. 16 100–104. 10.3969/j.issn.1004-1389.2007.03.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. Y., Shin R., Schachtman D. P. (2009). Ethylene mediates response and tolerance to potassium deprivation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 607–621. 10.1105/tpc.108.063099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser W. M. (1982). Correlation between changes in photosynthetic activity and changes in total protoplast volume in leaf tissue from hygro-, meso-and xerophytes under osmotic stress. Planta 154 538–545. 10.1007/BF00402997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács B., Puskás-Preszner A., Huzsvai L., Lévai L., Bódi E. (2015). Effect of molybdenum treatment on molybdenum concentrationand nitrate reduction in maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 96 38–44. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Zhang Z. S., Gao H. Y., Liu P., Dong S. T., Zhang J. W., et al. (2012). Effects of nitrogen on photosynthetic characteristics of leaves from two different stay-green corn (Zea mays L.) varieties at the grain-filling stage. Can. J. Plant Sci. 92 671–680. 10.4141/cjps2012-039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Wang Y., Okamoto M., Crawford N. M., Siddiqi M. Y., Glass A. D. (2007). Dissection of the AtNRT2.1:AtNRT2.2 inducible high-affinity nitrate transporter gene cluster. Plant Physiol. 143 425–433. 10.1104/pp.106.091223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Peng F., Wang X. (2010). Effects of bag-controlled release fertilizer on nitrogen utilization rate, growth and fruiting of the ‘Fuji’ apple. J. Plant Nutr. 33 1904–1913. 10.1080/01904167.2010.512050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Xiao W., Li L., Li D. M., Gao D. S., Fu X. L. (2017). Effect of exogenously applied molybdenum on its absorption and nitrate metabolism in strawberry seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 115 200–211. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. J., Zhang Y., Han W. X., Tang A. H., Shen J. L., Zhang F. S., et al. (2013). Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 494 459–462. 10.1038/nature11917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Gao J., Gao F., Liu P., Zhao B., Zhang J. W. (2018). Photosynthetic characteristics and chloroplast ultrastructure of summer Maize response to different nitrogen supplies. Front. Plant Sci. 9:576. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. W., Chen F., Wan Y. F., Liu D. B., Yu C. B., Wang Y. Q., et al. (2001). Effect of application of potassium on the yield and quality of Navel Orang. J. Fruit Sci. 18 272–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z. F., Ren T., Lu J. W., Li X. K., Cong R. H., Pan Y. H., et al. (2016). Main factors and mechanism leading to the decrease of photosynthetic efficiency of oilseed rape exposure to potassium deficiency. J. Plant Nutr. Fert. 22 122–131. 10.11674/zwyf.14407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. (2012). Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants. Cambridge, MA: Academic press. [Google Scholar]

- Munos S., Cazettes C., Fizames C., Gaymard F., Tillard P., Lepetit M., et al. (2004). Transcript profiling in the chl1-5 mutant of arabidopsis reveals a role of the nitrate transporter NRT1.1 in the regulation of another nitrate transporter, NRT2.1. Plant Cell 16 2433–2447. 10.1105/tpc.104.024380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhuis D., Loka D., Kawakami E., Pettigrew W. (2014). The physiology of potassium in crop production. Adv. Agron. 126 203–234. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800132-5.00003-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. L., Newstead S. (2014). Molecular basis of nitrate uptake by the plant nitrate transporter NRT1. 1. Nature 507 68–72. 10.1038/nature13116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perchlik M., Tegeder M. (2018). Leaf Amino Acid supply affects photosynthetic and plant nitrogen use efficiency under nitrogen stress. Plant Physiol. 178 174–188. 10.1104/pp.18.00597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew W. T. (2008). Potassium influences on yield and quality production for maize, wheat, soybean and cotton. Physiol. Plant. 133 670–681. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raese J. T., Drake R. S., Curry A. E. (2007). Nitrogen fertilizer influences fruit quality, soil nutrients and cover crops, leaf color and nitrogen content, biennial bearing and cold hardiness of ‘Golden Delicious’. J. Plant Nutr. 30 1585–1604. 10.1080/01904160701615483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B., Dong S., Zhao B., Liu P., Zhang J. (2017). Responses of nitrogen metabolism, uptake and translocation of maize to waterlogging at different growth stages. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1216. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan J., Wu X., Ye Y., Hardter R. (1998). Effect of potassium, magnesium and sulphur applied in different forms of fertilisers on free amino acid content in leaves of tea (Camellia sinensis L). J. Sci. Food Agric. 76 389–396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rufty T. W., Jackson W. A., Raper C. D. (1981). Nitrate reduction in roots as affected by the presence of potassium and by flux of nitrate through the roots. Plant Physiol. 68 605–609. 10.2307/4266953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J., Romero L. (2002). Relationship between potassium fertilisation and nitrate assimilation in leaves and fruits of cucumber (Cucumis sativus) plants. Ann. Appl. Biol. 140 241–245. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2002.tb00177.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sattelmacher B., Horst W. J., Becker H. C. (1994). Factors that contribute to genetic variation for nutrient efficiency of crop plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil 157 215–224. 10.1002/jpln.19941570309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y., Cui H., Wang M., Liu X. (2017). Nitrate reductase is regulated by CIRCADIAN CLOCK-ASSOCIATED1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Soil 416 477–485. 10.1007/s11104-017-3208-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tränkner M., Tavakol E., Jákli B. (2018). Functioning of potassium and magnesium in photosynthesis, photosynthate translocation and photoprotection. Physiol. Plant. 163 414–431. 10.1111/ppl.12747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Sha J. C., Chen Q., Xu X. X., Zhu Z. L., Ge S. F., et al. (2020). Exogenous Abscisic acid regulates distribution of 13C and 15N and anthocyanin synthesis in ‘Red Fuji’ apple fruit under high nitrogen supply. Front. Plant Sci. 10:1738. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Okamoto M., Xing X., Crawford N. M. (2003). Microarray analysis of the nitrate response in Arabidopsis roots and shoots reveals over 1,000 rapidly responding genes and new linkages to glucose, trehalose-6-phosphate, iron, and sulfate metabolism. Plant Physiol. 132 556–567. 10.1104/pp.103.021253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Z., Zhang H. P., Huang X. S., Wang J. Z., Cheng R., Chen G. D., et al. (2017). Effect of potassium supply on plant potassium distribution and growth and leaf photosynthetic capacity of Pyrus pyrifolia. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 40 60–67. 10.7685/jnau.201603054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warner J., Zhang T. Q., Hao X. (2004). Effects of nitrogen fertilization on fruit yield and quality of processing tomatoes. Can. J. Plant Sci. 84 865–871. 10.4141/P03-099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S. S., Wang X. Y., Shi D. Y., Li Y. H., Zhang J. W., Dong S. T., et al. (2016). The mechanisms of low nitrogen induced weakened photosynthesis in summer maize (Zea mays L.) under field conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 105 118–128. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P. J., Karley A. J. (2010). Potassium Cell Biology of Metals and Nutrients. Berlin: Springer, 199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Xu H., Dong S., Chu J., Dai X., He M. (2019). Optimised nitrogen allocation favours improvement in canopy photosynthetic nitrogen-use efficiency: evidence from late-sown winter wheat. Environ. Exp. Bot. 159 75–86. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.12.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Yang F., Tian X. (2009). Coronatine-induced lateral formation in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) seedlings under potassium-sufficient and –deficient conditions in relation to auxin. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 172 435–444. 10.1002/jpln.200800116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. X., Zhang W. (2017). Effects of controlled-release urea combined with conventional urea on nitrogen uptake, root yield, and quality of Platycodon grandiflorum. J. Plant Nutr. 40 662–672. 10.1080/01904167.2016.1249799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.