Abstract

Background

Chronic norovirus infection in immunocompromised patients can be severe, and presently there is no effective treatment. Adoptive transfer of virus-specific T cells has proven to be safe and effective for the treatment of many viral infections, and this could represent a novel treatment approach for chronic norovirus infection. Hence, we sought to generate human norovirus-specific T cells (NSTs) that can recognize different viral sequences.

Methods

Norovirus-specific T cells were generated from peripheral blood of healthy donors by stimulation with overlapping peptide libraries spanning the entire coding sequence of the norovirus genome.

Results

We successfully generated T cells targeting multiple norovirus antigens with a mean 4.2 ± 0.5-fold expansion after 10 days. Norovirus-specific T cells comprised both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that expressed markers for central memory and effector memory phenotype with minimal expression of coinhibitory molecules, and they were polyfunctional based on cytokine production. We identified novel CD4- and CD8-restricted immunodominant epitopes within NS6 and VP1 antigens. Furthermore, NSTs showed a high degree of cross-reactivity to multiple variant epitopes from clinical isolates.

Conclusions

Our findings identify immunodominant human norovirus T-cell epitopes and demonstrate that it is feasible to generate potent NSTs from third-party donors for use in antiviral immunotherapy.

Keywords: adoptive immunotherapy, norovirus, primary immunodeficiency, T cells, transplantation

We generated polyfunctional norovirus-specific T cells that show cross-reactivity to variant viral epitopes and may be suitable for clinical use. We have determined, for the first time, a hierarchy of immunodominance of human norovirus antigens and identified multiple T-cell epitopes.

Norovirus is a positive-sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus of the family Caliciviridae, and it is a leading worldwide cause of acute gastroenteritis [1, 2]. The genome is organized into open reading frames (ORFs) 1, 2, and 3, which encode nonstructural proteins NS1-7, major capsid protein VP1, and minor capsid protein VP2, respectively. Human norovirus has high genetic diversity, and it clusters into 3 genogroups (GI, GII, and GIV) and over 25 genotypes. Of these, GII.4 is responsible for the majority of human infections and outbreaks. These infections in immunocompetent hosts typically cause self-limiting nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea lasting 1–3 days. However, norovirus infection can result in prolonged symptoms that persist for months to years, particularly in immunocompromised patients, leading to chronic diarrhea and malabsorption [3, 4]. The exact prevalence of norovirus infection among immunocompromised hosts is unknown, but norovirus was identified in 13% of immunocompromised patients with diarrhea [5]. The severe impact of chronic norovirus infection has become increasingly evident among patients with primary immunodeficiencies [6–8], solid organ transplants [9, 10], and hematopoietic stem cell transplants [11]. Currently, there are no approved antiviral therapies to treat norovirus and no approved vaccines for disease prevention. Nitazoxanide has been used in a small randomized study with evidence of symptomatic improvement [12]; however, in immunocompromised patients, this improvement is often partial and rarely results in viral clearance.

Although advances in human norovirus therapeutic and vaccine research have been hampered by technical challenges [13], efforts to understand protective immunity against norovirus are ongoing. In the animal model of murine norovirus, both B cells and T cells are necessary to clear infection [14, 15]. In human case reports and case series, the return of T-cell function after human immunodeficiency virus treatment, stem cell transplantation, or gene therapy is necessary to clear norovirus infection [16, 17]. Norovirus-specific memory T-cell responses have recently been demonstrated in healthy donors [18], indicating that virus-specific T-cell therapy holds promise for the treatment of chronic norovirus infection. To date, only a single CD8-restricted epitope in VP1 has been described, and the breadth of T-cell responses to human norovirus remains unknown [19].

Adoptive immunotherapy with ex vivo expanded virus-specific T cells (VSTs) has been successful in preventing and treating viral infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [20–22]. Use of banked “off-the-shelf” VSTs derived from partially human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched third-party donors has also been used with minimal toxicity [23–25]. Although most studies have targeted systemic viruses such as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), recent studies have shown that VSTs may be effective against organ-specific viral infections, such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) [26]. Thus, norovirus could be a suitable candidate for adoptive immunotherapy, and successful ex vivo expansion of norovirus-specific T cells (NSTs) could provide a new therapeutic strategy against chronic norovirus infection.

In this study, we show that it is feasible to generate potent NSTs from the peripheral blood of healthy donors using a good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant methodology. We also characterized the cellular immune response and identified novel immunodominant CD4- and CD8-restricted epitopes within NS6 and VP1 antigens. We anticipate that these results will (1) facilitate the development of NSTs as a novel off-the-shelf therapeutic for patients with chronic norovirus infection and (2) help to identify critical epitopes for vaccines to prevent infection in high-risk individuals.

METHODS

Donors

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy volunteers were obtained from Children’s National Medical Center (Washington, DC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Blood Bank (Bethesda, MD) under informed consent approved at each institution in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Plasma samples were screened for the presence or absence of antibodies against norovirus by adaptation of a previously described enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [25]. Stools from patients with chronic norovirus infection were obtained from patients at the NIH Clinical Center after patients signed informed consent.

Peptides

For stimulation, we used custom-ordered pepmixes (peptide libraries of 15-mers overlapping by 10 amino acids) (A&A Labs, San Diego, CA) encompassing the entire coding sequence (ORFs 1–3) of norovirus Hu/GII/Au/2012/GII.Pe_GII.4Sydney2012/NSW0514 (GenBank no. JX459908).

Generation of Norovirus-Specific T Cells

The PBMCs were pulsed with norovirus pepmixes pooled or individually (200 ng/peptide/15 × 106 PBMCs) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After incubation, cells were resuspended with interleukin (IL)-4 (400 IU/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and IL-7 (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems) in CTL media consisting of 45% Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (GE Healthcare, Logan, UT), 45% Click’s medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA), 10% human AB serum (Gemini BioProducts, West Sacramento, CA), and supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMax (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), then transferred to a G-Rex10 device (Wilson Wolf, Minneapolis, MN). Media and cytokines were replenished on day 7. On day 10, cells were harvested and evaluated for antigen specificity and functionality.

Interferon-γ Enzyme-Linked Immunospot Assay

Antigen specificity of T cells was measured by interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) (Millipore, Burlington, MA). T cells were plated at 1 × 105 per well with no peptide, actin (control), or each of the individual norovirus pepmixes (200 ng/peptide per well). Plates were sent for IFN-γ spot-forming cell (SFC) counting (Zellnet Consulting, Fort Lee, NJ).

Multiplex Cytokine Assay

Norovirus-specific T cells were plated at 1 × 105/well in 96-well plates, stimulated with pooled pepmixes (200 ng/peptide per well) or control actin peptide, and incubated overnight. Supernatants were harvested, and the cytokine profile analysis was performed using the Bio-plex Pro Human 17-plex Cytokine Assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Immunophenotyping

Norovirus-specific T cells were stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD25, CD45RO, CD62L, CD127, CCR7, PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3, and CTLA-4 (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany; BioLegend, San Diego, CA). All samples were acquired on a CytoFLEX cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), and the data were analyzed with FlowJo X (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR).

Intracellular Cytokine Staining

A total of 1 × 106 NSTs were plated in a 96-well plate and stimulated with pooled pepmixes or individual peptides (200 ng/peptide per well) or actin (control) in the presence of Brefeldin A (Golgiplug; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and CD28/CD49d (BD Biosciences) for 6 hours. T cells were fixed, permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences), and stained with IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec).

Epitope Mapping

Norovirus-specific T cells were tested for specificity to NS6 and VP1 individual peptides by IFN-γ ELISpot. The NS6 and VP1 15-mer peptides were pooled according to the matrix. Cross-reactive pools were analyzed, and individual peptides were tested to confirm epitope specificity. To identify minimal epitopes, a series of 9-mer peptides overlapping by 8 amino acids spanning immunogenic 15-mer peptides were generated. The HLA restriction of antigen recognition was tested using blocking antibodies against HLA class I and II (Dako Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). To determine the restricted HLA allele, NSTs were plated at 1 × 105/well with partially HLA-matched phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-treated lymphoblasts (PHA-blasts, 25 Gy irradiated) either alone or pulsed with peptide (10 µg/mL).

Data Analysis

Results were evaluated using descriptive statistics (means, standard error of the mean [SEM], and ranges). Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare the 2 groups. Data analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Norovirus-Specific T Cells Can Be Expanded From Healthy Seropositive Donors

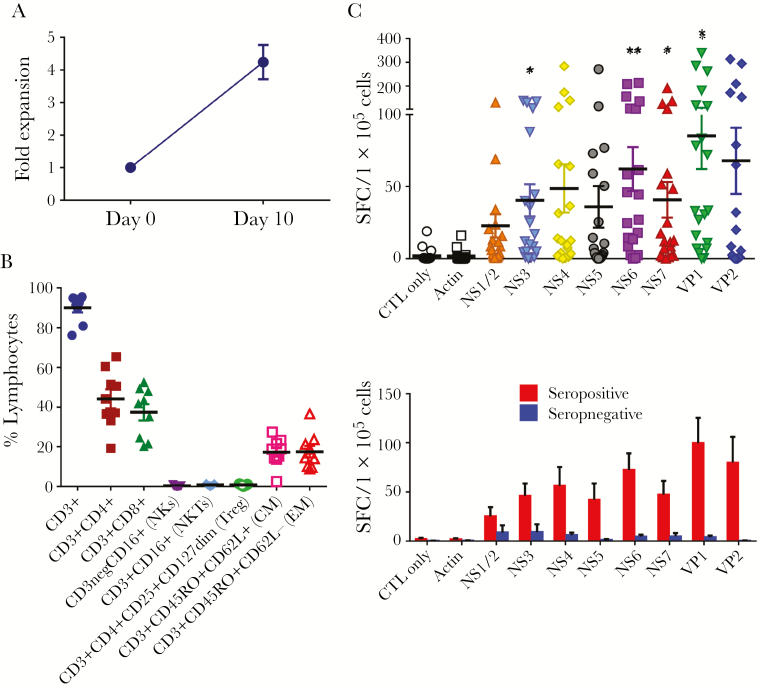

To evaluate whether NSTs can be expanded from healthy norovirus-seropositive donors, PBMCs (n = 20) were stimulated with norovirus pepmixes spanning all viral antigens (NS1-2, NS3 [NTPase], NS4, NS5 [VPg], NS6 [protease], NS7 [RNA-dependent RNA polymerase], VP1, and VP2) and cultured for 10 days, in accordance with our previous report [26]. After stimulation we achieved a mean 4.2 ± 0.5-fold increase (range, 1.0–8.8) in total cell numbers (Figure 1A). Phenotyping analysis revealed that these expanded cells were CD3+ T cells (mean ± SEM, 90.0% ± 2.3%) with a mixture of CD4+ T cells (44.2% ± 4.8%) and CD8+ T cells (37.3% ± 4.1%) (Figure 1B). There was no outgrowth of natural killer cells and regulatory T cells. The expanded T cells expressed both central memory (17.2% ± 2.3%) and effector memory (17.4% ± 2.9%) markers. We next determined the specificity of the expanded T cells against norovirus antigens by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Expanded cells specifically released IFN-γ against NS1/2 (22.7 ± 8.0 SFC/1 × 105 cells; P = .10), NS3 (40.4 ± 11.1; P = .01), NS4 (48.6 ± 16.7; P = .06), NS5 (35.9 ± 14.4; P = .14), NS6 (62.1 ± 15.3; P < .01), NS7 (40.7 ± 12.3; P = .03), VP1 (85.2 ± 23.0; P = .01), and VP2 (67.8 ± 23.0; P = .06), compared with actin control (1.6 ± 0.8) (Figure 1C). We examined an association between serostatus against norovirus and T-cell responses. Norovirus-specific T cells were only detected in T-cell products derived from seropositive donors, whereas T cells from seronegative donors did not demonstrate specificity (Figure 1D). Together, these data suggest that T cells targeting multiple norovirus antigens can be readily ex vivo expanded in 10 days from seropositive donors.

Figure 1.

Norovirus-specific T-cells can be generated from peripheral blood of norovirus-seropositive donors. (A) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors were stimulated with norovirus pepmixes on day 0. Fold expansion was measured 10 days after stimulation based on absolute cell counting in total cell numbers (n = 20, mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (B) Phenotype of the expanded cells was accessed by flow cytometry for T-cell markers (CD3, CD4, and CD8), natural killer (NK) cell markers (CD16), and memory subsets (CD45RO and CD62L) (n = 9, mean ± SEM). (C) Specificity of the expanded cells with response to norovirus antigens stimulation was assayed by interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay (n = 20, mean ± SEM). Unstimulated T cells (CTL only) and stimulation with actin were used as negative controls. Results are presented as spot-forming cells (SFC)/1 × 105 cells. The number of spots were compared with those from actin control (*, P < .05 and **, P < .01; 2-tailed Student’s t test). (D) Specificity of the expanded cells against norovirus antigens between norovirus-seropositive donors (n = 17) and seronegative donors (n = 3) by IFN-γ ELISpot (mean ± SEM). CM, central memory T-cells (CD45RO+CD62L+); EM, effector memory T-cells (CD45RO+CD62L−); NKs, natural killer cells (CD3−CD16+); NKTs, natural killer T cells (CD3+CD16+); Treg, regulatory T cells (CD3+CD4+CD25+CD127dim).

Characterization of Norovirus-Specific T Cells

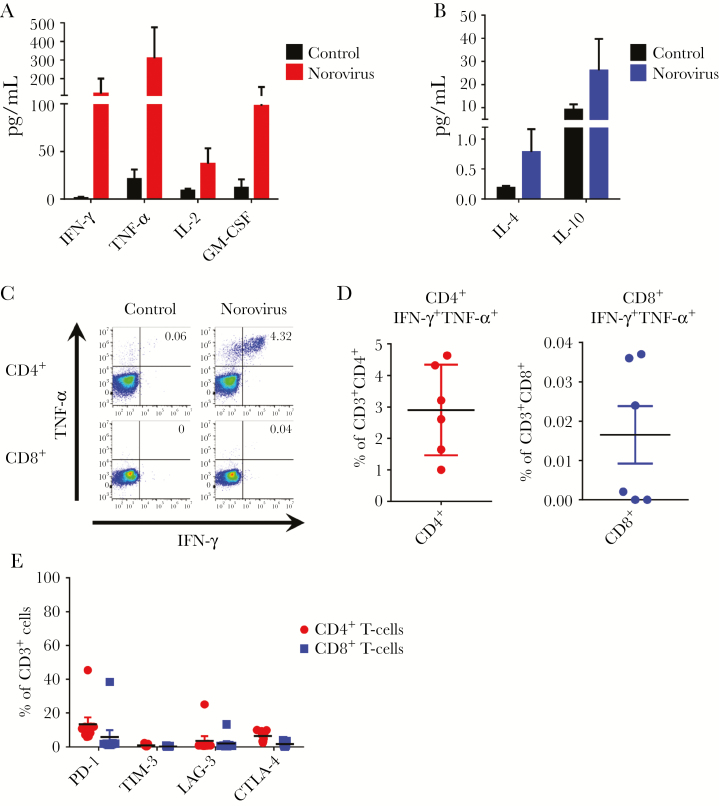

Recent studies suggest that polyfunctional antigen-specific T cells have improved cytolytic function and superior in vivo activity [27]. Thus, we evaluated the production of multiple proinflammatory cytokines by NSTs to determine their polyfunctionality. Norovirus-specific T cells released IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor upon stimulation with norovirus pepmixes (Figure 2A) with minimal production of regulatory cytokines including IL-4 and IL-10 (Figure 2B). To further evaluate whether NSTs produce more than 1 cytokine, we performed intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α staining, gating on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 2C). After restimulation with norovirus pepmixes, IFN-γ+TNF-α + T cells were predominantly detected in the CD4+ T-cell compartment (2.9% ± 0.5%) with a very limited CD8+ component (Figure 2D). We measured coinhibitory receptors including PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3, and CTLA-4 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Despite restimulation with norovirus antigens, flow analysis revealed low expression levels of coinhibitory molecules (Figure 2E). Together, these data indicate that the ex vivo-expanded NSTs are polyclonal and polyfunctional.

Figure 2.

Norovirus-specific T-cells are polyfunctional. Norovirus-specific T cells were tested for secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (A) and regulatory cytokines (B) in response to stimulation with pooled pepmixes. Cytokines were measured in cell supernatant after 24-hour stimulation by Luminex assay. Stimulation with actin was used as a control (n = 7, mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (C) Polycytokine (interferon [IFN]-γ and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α) production in response to pooled norovirus pepmixes as evaluated by intracellular cytokine staining from CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 1 representative donor (gated on CD3+). Stimulation with actin was used as a negative control. (D) Summary results of double cytokine (IFN-γ and TNF-α) producing cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations (n = 6, mean ± SEM). (E) Expression of coinhibitory markers of norovirus-specific T cells by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after restimulation with pooled norovirus pepmixes (n = 9, mean ± SEM). GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IL, interleukin.

Identification of T-Cell Epitopes

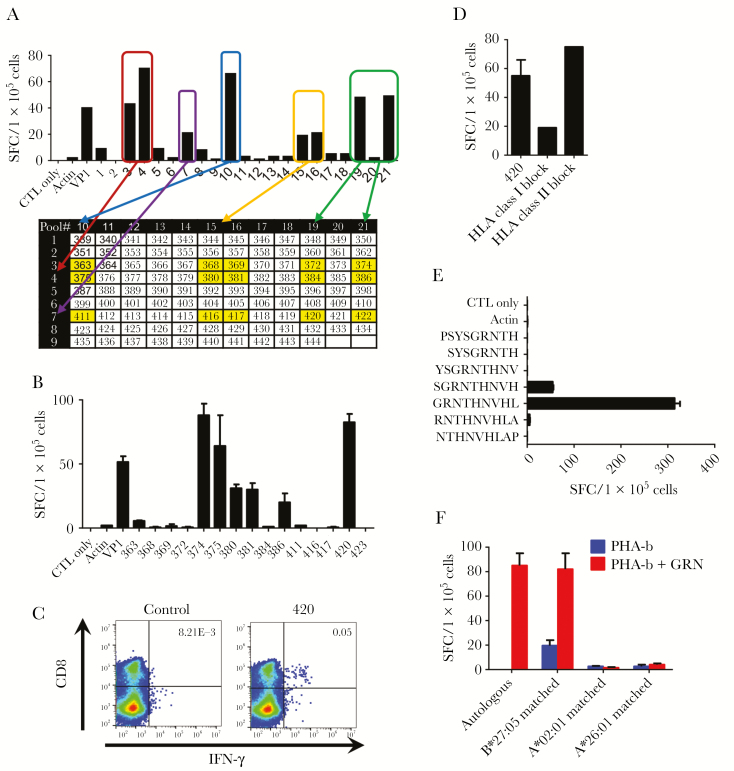

We determined a hierarchy of immunodominance based on the number of responding donors and the magnitude of reactive cells (Figure 1C, Table 1). We selected NS6 and VP1, representing a nonstructural and structural protein, respectively, for further epitope mapping because the highest percentage of donors responded strongly to these antigens. To avoid antigen competition, we stimulated PBMCs from healthy donors with a combined pool of NS6 and VP1 pepmixes and cultured for 10 days. The resultant cells showed a mean expansion of 3.4 ± 0.4-fold (range, 1.9–6.7) in total cell numbers (Supplementary Figure S1A). Of note, they were specific for both NS6 (95.1 ± 21.6 SFC/1 × 105 cells) and VP1 antigens (140.0 ± 29.4) at higher frequencies of specific cells compared with those achieved using whole pepmixes (Supplementary Figure S1B). Next, we analyzed the breadth of epitope specificity of NS6 and VP1 utilizing these NS6/VP1-specific T cells. A representative example of mapping for VP1 is shown in Figure 3. In this approach, 106 15-mers spanning VP1 protein were divided into 21 mini-pools such that each peptide is uniquely present in 2 pools. Using this method, the T-cell product recognized 8 mini-pools (3, 4, 7, 10, 15, 16, 19, and 21), and individual 15-mers that were present in the 2 of the peptides were selected (Figure 3A). Testing of the single peptides by IFN-γ ELISpot revealed recognition of the single peptides 374, 375, 380, 381, 386, and 420 (Figure 3B). The HLA restriction of these peptides was evaluated with intracellular IFN-γ staining. CD8+ T cells released IFN-γ in response to 15-mer peptide 420 PSYSGRNTHNVHLAP (PSY), indicating that this peptide was an HLA class I-restricted epitope (Figure 3C). This was further confirmed by using an HLA-blocking experiment in IFN-γ ELISpot (Figure 3D). We next determined the minimal 9-mer epitope and restricted HLA class I allele of this peptide. The NST product was rescreened against a panel of 9-mer peptides overlapping by 8 amino acids spanning the 15-mer PSY peptide. The T cells secreted IFN-γ upon stimulation with GRNTHNVHL (GRN), confirming that GRN was the minimal 9-mer epitope (Figure 3E). Finally, to determine the restricted HLA allele of GRN, we applied an algorithm (NetMHC [www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetMHCpan/]) that predicted strong binding to HLA-B*27:05 among the HLA types of the donor. We subsequently tested this HLA restriction by using autologous and partially HLA-matched peptide-pulsed PHA blasts in an ELISpot assay. Norovirus-specific T cells recognized peptide-pulsed PHA blasts matched for HLA-B*27:05 with no reactivity against PHA blasts matched at other HLA alleles (Figure 3F). We accessed the breadth of specificity to NS6 using the same approach (Supplementary Figure S2). The complete NS6/VP1 mapping data of a total of 31 CD4+ and CD8+-restricted epitopes in 11 donors tested is summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Hierarchy of Immunodominance Among Human Norovirus Antigens

| Response, SFC/1 × 105 Cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | Responders (n = 20)a | Mean ± SEM | Median (Range) |

| NS1/2 | 5 | 23 ± 8 | 9 (0–130) |

| NS3 | 5 | 40 ± 11 | 15 (0–138) |

| NS4 | 7 | 49 ± 17 | 13 (0–284) |

| NS5 | 6 | 36 ± 14 | 6 (0–271) |

| NS6 | 11 | 62 ± 15 | 36 (0–213) |

| NS7 | 7 | 41 ± 12 | 12 (0–191) |

| VP1 | 13 | 85 ± 23 | 33 (0–340) |

| VP2 | 8 | 68 ± 23 | 7 (0–313) |

Abbreviations: SEM, standard error of the mean; SFC, spot-forming cells.

aResponses that exceeded 5× actin control and were at least 20 SFC/1 × 105 cells were regarded as significant.

Figure 3.

Identification of VP1 CD8-restricted T-cell epitopes. T-cell epitope mapping for VP1 protein was performed, and results from 1 representative donor are shown. (A) The breadth of T-cell reactivity was evaluated using a total of 21 mini-peptide pools, each containing 8–12 peptides, spanning the entire VP1 protein. Mini-pools were made in such a way that each peptide was present in 2 pools. A norovirus-specific T-cell product was stimulated with 21 mini-peptide pools, and the T-cell responses were measured by interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot). Responses to pools 3 and 10, 3 and 15, 3 and 16, 3 and 19, 3 and 21, 4 and 10, 4 and 15, 4 and 16, 4 and 19, 4 and 21, 7 and 10, 7 and 15, 7 and 16, 7 and 19, and 7 and 21 may be induced by individual 15-mer peptides 363, 368, 369, 372, 374, 375, 380, 381, 384, 386, 411, 416, 417, 420, and 422, respectively (yellow cells). (B) Testing of these single peptides by IFN-γ ELISpot revealed recognition of the single 15-mer peptides of 374, 375, 380, 381, 386, and 420 (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (C) Intracellular IFN-γ staining was used to evaluate the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-restriction of the single 15-mer peptides (gated on CD3+). Results indicating CD8-restricted epitopes are shown. (D) Blocking experiments with HLA class I and II blocking antibodies by IFN-γ ELISpot (mean ± SEM). (E) To identify the minimal 9-mer epitope, recognition against a panel of 9-mers overlapping by 8 amino acids spanning the sequence of 420 was evaluated by IFN-γ ELISpot (mean ± SEM). (F) Restricted HLA allele was evaluated by IFN-γ ELISpot using allogeneic HLA partially matched phytohemagglutinin (PHA) blasts alone or pulsed with GRNTHNVHL (GRN) peptide (mean ± SEM). Autologous PHA blasts pulsed with GRN were used as a positive control. SFC, spot-forming cells.

Table 2.

Peptide Sequences of Novel CD4-Restricted T-Cell Epitopes Identified in Human Norovirus NS6 and VP1

| Norovirus Antigen | Peptide Sequence | Amino Acid Location | HLA-DRB1 | HLA-DQB1 | HLA-DPB1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS6 | GSGWGFWVSPSLFIT | 1021–1035 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 |

| 11:04, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | − | |||

| 04:05, 07:01 | 02:02, 04:01 | 02:01, 05:01 | |||

| FWVSPSLFITSTHVI | 1026–1040 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| 11:04, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | − | |||

| 04:05, 07:01 | 02:02, 04:01 | 02:01, 05:01 | |||

| SLFITSTHVIPQSAK | 1031–1046 | 11:04, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | − | |

| PQSAKEFFGVPIKQI | 1041–1955 | 04:05, 07:01 | 02:02, 04:01 | 02:01, 05:01 | |

| EFFGVPIKQIQIHKS | 1046–1060 | 04:05, 07:01 | 02:02, 04:01 | 02:01, 05:01 | |

| PIKQIQIHKSGEFCR | 1051–1065 | 15:01, 13:01 | 06:02, 06:03 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| 15:01, 12:02 | 03:01, 06:02 | 05:01, 05:01 | |||

| 01:01, 13:01 | 05:01, 06:03 | 03:01, 03:01 | |||

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| LRFPKPIRTDVTGMI | 1066–1080 | 15:01, 12:02 | 03:01, 06:02 | 05:01, 05:01 | |

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| PIRTDVTGMILEEGA | 1071–1085 | 15:01, 12:02 | 03:01, 06:02 | 05:01, 05:01 | |

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| LEEGAPEGTVATLLI | 1081–1095 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| PEGTVATLLIKRPTG | 1086–1100 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| GNDYVVIGVHTAAAR | 1156–1170 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| 03:01, 04:04 | 02:01, 03:02 | 02:01, 03:01 | |||

| 15:01, 12:02 | 03:01, 06:02 | 05:01, 05:01 | |||

| 04:04, 11:01 | 03:01, 03:02 | 04:01, 04:01 | |||

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| VIGVHTAAARGGNTV | 1161–1175 | 15:01, 12:02 | 03:01, 06:02 | 05:01, 05:01 | |

| 04:04, 11:01 | 03:01, 03:02 | 04:01, 04:01 | |||

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| VP1 | PVVGAAIAAPVAGQQ | 31–45 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 |

| LGPDLNPYLSHLARM | 81–95 | 15:01, 13:01 | 06:02, 06:03 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| VRNNFYHYNQSNDPT | 161–175 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| IKLIAMLYTPLRANN | 176–190 | 15:01, 13:01 | 06:02, 06:03 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| 01:01, 13:01 | 05:01, 06:03 | 03:01, 03:01 | |||

| MLYTPLRANNAGDDV | 181–195 | 01:01, 13:01 | 05:01, 06:03 | 03:01, 03:01 | |

| AGDDVFTVSCRVLTR | 186–200 | 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |

| PSPDFDFIFLVPPTV | 206–220 | 01:01, 11:01 | 03:01, 05:01 | 04:01, 04:02 | |

| 10:01, 04:11 | 03:02, 05:01 | 04:02, 10:01 | |||

| 01:01, 13:01 | 05:01, 06:03 | 03:01, 03:01 | |||

| DFIFLVPPTVESRTK | 211–225 | 01:01, 11:01 | 03:01, 05:01 | 04:01, 04:02 | |

| 10:01, 04:11 | 03:02, 05:01 | 04:02, 10:01 | |||

| 01:01, 13:01 | 05:01, 06:03 | 03:01, 03:01 | |||

| EMTNSRFPIPLEKLF | 236–250 | 03:01, 04:04 | 02:01, 03:02 | 02:01, 03:01 | |

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| RFPIPLEKLFTGPSS | 241–255 | 03:01, 04:04 | 02:01, 03:02 | 02:01, 03:01 | |

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| SRNYTMNLASQNWND | 296–310 | 10:01, 04:11 | 03:02, 05:01 | 04:02, 10:01 | |

| 11:04, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | − | |||

| 04:04, 11:01 | 03:01, 03:02 | 04:01, 04:01 | |||

| 11:01, 13:02 | 03:01, 06:04 | 04:01, 14:01 | |||

| EWVQYFYQEAAPAQS | 456–470 | 01:01, 11:01 | 03:01, 05:01 | 04:01, 04:02 | |

| APAQSDVALLRFVNP | 466–480 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| DVALLRFVNPDTGRV | 471–485 | 11:01, 07:01 | 02:02, 03:01 | 02:01, 04:01 | |

| 04:05, 07:01 | 02:02, 04:01 | 02:01, 05:01 | |||

| DTGRVLFECKLHKSG | 481–495 | 03:01, 04:04 | 02:01, 03:02 | 02:01, 03:01 | |

| VNQFYTLAPMGNGTG | 526–540 | 10:01, 04:11 | 03:02, 05:01 | 04:02, 10:01 |

Table 3.

Peptide Sequences of Novel CD8-Restricted T-Cell Epitopes Identified in Human Norovirus NS6 and VP1

| Norovirus Antigen | Peptide Sequence | Amino Acid Location | HLA Restriction |

|---|---|---|---|

| NS6 | YVVIGVHTA | 1159–1167 | A*02:06 |

| VP1 | GRNTHNVHL | 410–418 | B*27:05 |

| VP1 | FPGEQLLFF | 426–434 | B*35:01 |

Cross-Reactivity of Norovirus-Specific T Cells

The norovirus peptide library used in this study was based on the GII.4 Sydney 2012 strain, which is currently the most prevalent strain worldwide. However, many other norovirus genotypes, recombinants, and strain variants cocirculate, and the RNA genome can evolve rapidly under selective pressure [28]. To assess whether the newly identified NST epitopes were conserved among different norovirus strains, we aligned their amino acid sequences with those available in the public National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. In addition, the Sydney 2012 peptides were compared with an internal unpublished sequence database generated from virus in stools, many of which were from patients with chronic norovirus infection (Supplementary Table 1). Among identified epitopes including both HLA class I- and II-restricted, 1 to 7 amino acid sequences were altered in 22 of the 31 epitopes. We next evaluated the cross-reactivity of NSTs against variant epitopes by IFN-γ ELISpot. Although the recognition of CD8-restricted epitope GRN was disrupted when the amino acid was altered at a predicted anchor site (Figure 4A), NSTs widely responded to variants of other CD8 (Figure 4B and C) and CD4-restricted epitopes (Figure 4D). A calculated cross-reactivity index (variant response/GII.4 Sydney 2012 response) was used to normalize across the different variant epitopes, with 1 indicating an equal response to original and variant peptide [29] (Supplementary Table 1). More important, responses were highly cross-reactive against different norovirus strains and variable epitopes in both NS6 (cross-reactivity index, 0.36 ± 0.06) and VP1 (0.60 ± 0.06) (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Cross-reactivity of norovirus-specific T cells to variant epitopes. Norovirus-specific T cells were stimulated with CD8-restricted T-cell epitopes GRNTHNVHL (A), YVVIGVHTA (B), FPGEQLLFF (C), and CD4-restricted T-cell epitope PIKQIQIHKSGEFCR (D), as well as altered versions as identified in database or clinical isolates. Responses were measured by interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (E) Cross-reactivity of norovirus-specific T cells against variant epitopes was measured by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Data are cross-reactivity indices (variant response/GII.4 Sydney 2012 response) of 45 NS6 (n = 9) and 26 VP1 epitopes (n = 11) (mean ± SEM). SFC, spot-forming cells.

DISCUSSION

Chronic norovirus infection in immunocompromised patients is associated with severe morbidity and potential risk of death due to malnutrition and end-organ damage. Currently, there is no effective treatment. In the present study, we show that NST products can be generated from healthy seropositive donors using a rapid ex vivo expansion, GMP-applicable, and reproducible platform approach. Cell yields were moderate (median 4.2-fold increase), but they should allow generation of >108 NSTs from as little as 25 million PBMCs, which would permit multiple doses on the order of 107 NSTs/m2. Norovirus-specific T cells were polyclonal with both CD4+ and CD8+ populations, and they showed reactivity to multiple norovirus antigens with a polyfunctional cytokine profile. Moreover, we defined a hierarchy of immunodominance and identified multiple novel CD4- and CD8-restricted epitopes within NS6 and VP1 antigens. This profile is comparable to the expansion of adenovirus-specific T cells, which tend to have a CD4+ T-cell predominance [30]. Use of third-party VSTs with HLA class II-restricted adenovirus hexon protein responses has been successful across several studies [23, 24, 31], suggesting that CD4 T cells may be beneficial in targeting gastrointestinal viruses.

We also demonstrated the cross-reactivity of NSTs against variant viral epitopes, which may be indicative of broad clinical application against different circulating viral strains. This is the first report describing the manufacture and comprehensive epitope mapping of NSTs as a proof-of-principle demonstration for the development of a novel off-the-shelf T-cell immunotherapeutic targeting norovirus.

Identification of immunogenic viral antigens is essential for developing immunotherapies. To date, comprehensive T-cell epitope mapping data are lacking in human norovirus, although a small number of epitopes have been described [18, 19, 32]. In the current study, we generated NSTs by stimulating with pooled pepmixes spanning the ORFs of the entire norovirus genome and analyzed the breadth of epitope specificity. Among the 8 antigens, NS6 and VP1 were recognized by most of the donors and induced the highest magnitude of responses. We found that NS6 and VP1 immunogenic epitopes were predominantly HLA class II-restricted. The predominance of CD4+-reactive T cells might be compatible with the notion that murine norovirus reduces the expression of major histocompatibility complex class I proteins and impairs CD8+ T-cell recognition and activation [33]. Gerdemann et al [34] demonstrated similar results in manufacturing human herpesvirus 6-specific T cells, which might also be explained by herpesvirus-derived immune modulation. Despite the bias of CD4+-reactive T cells, we were able to identify 3 immunodominant CD8-restricted epitopes, which produced IFN-γ in response to single peptide stimulation.

The strategy we used to identify CD4- and CD8-restricted epitopes was based on the previous successful epitope mapping approach evaluated with EBV-specific T cells [35]. One potential problem with this method is that not all epitopes may be detected using ex vivo expanded T cells. In a recent study, Malm et al [19] identified a human norovirus HLA-A*02:01-restricted minimal 10-mer epitope TMFPHIIVDV (TMF) in VP1 antigen by screening unexpanded PBMCs with a matrix peptide approach. We also evaluated NSTs generated from 4 HLA-A*02:01+ donors, but we did not identify the TMF epitope. One possible explanation for this difference might be antigenic competition for binding to HLA molecules that could lead to underdetection of TMF epitope in expanding T cells with multiple peptide libraries. However, our GMP-compliant, overlapping, peptide-based method enabled us to target multiple epitopes within 2 norovirus antigens, which could minimize the likelihood of viral immune escape and may have superior clinical efficacy compared with targeting a single antigen in isolation [36].

Norovirus, similar to other RNA viruses, is known to evolve quickly and undergo rapid immune escape. An analysis of norovirus variants present in the stool of immunocompromised patients with chronic norovirus infection showed a diverse norovirus population [37]. Therefore, we compared our newly identified epitope sequences with virus sequences from the patients with chronic norovirus infection and observed a high degree of cross-reactivity in NSTs targeting NS6 and VP1, including both CD4- and CD8-restricted epitopes. Cross-reactive T-cell responses have been shown to play a role in protection among viruses with a high degree of sequence identity such as dengue virus and Zika virus [38]. This is also similar to previous observations with adenovirus-specific T cells that were reported to be cross-reactive to different adenovirus serogroups [39]. Furthermore, Muftuoglu et al [26] recently showed the advantage of shared epitopes among the members of the Polyomaviridae family by administering BK virus-specific T cells to treat patients with PML. They found that patients had reduced clinical symptoms and clearance of JC virus after the infusion of T-cell products. Thus, the cross-reactivity of NST responses to variant epitopes has promising implications for adoptive immunotherapy for patients with chronic norovirus infection.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we show that functionally active NSTs can be generated from seropositive healthy donors in 10 days. These products have wide norovirus antigen recognition and show polyfunctionality, polyclonality, and cross-reactivity to variant epitopes. Furthermore, the identification of multiple novel CD4- and CD8-restricted epitopes may help to identify protective immunogens for a norovirus vaccine as well as a rationale for the creation of third-party banks of NST products. Therefore, we envision that this strategy could translate to future clinical studies to evaluate the safety and efficacy of vaccine approaches and adoptively transferred third-party, partially HLA-matched NST products.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank our blood donors for participation in this study, as well as the staffs of the Center for Cancer and Immunology Research at Children’s National Medical Center and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center. We are also grateful to Dr. Alessandro Sette for his guidance.

Financial support. This work was funded by grants from Be The Match and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (Amy Strelzer Manasevit Award; to P. J. H.), the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (K23-HL136783-01; to M. D. K.), the Jeffrey Modell Foundation, and the Board of Visitors of the Children’s National Health System.

Potential conflicts of interest. P. J. H. is a founder and director of Mana Therapeutics. C. M. B. is on the scientific advisory boards for Cellectis and has stock options in Neximmune and Torque Therapeutics and has stock or ownership in Mana Therapeutics. R. H., G. M. S., S. V. S., J. I. C., K. Y. G., C. M. B., and M. D. K. have filed a patent application based on the findings in this paper. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: Children’s National Medical Center Research Symposium, Washington, DC, 2 April 2019.

References

- 1. Glass RI, Parashar UD, Estes MK. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1776–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robilotti E, Deresinski S, Pinsky BA. Norovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015; 28:134–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bok K, Green KY. Norovirus gastroenteritis in immunocompromised patients. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Green KY. Norovirus infection in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20:717–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bok K, Prevots DR, Binder AM, et al. Epidemiology of norovirus infection among immunocompromised patients at a tertiary care research hospital, 2010–2013. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3:ofw169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frange P, Touzot F, Debré M, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of norovirus fecal shedding in children with inherited immune deficiencies. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woodward J, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Kumararatne D. Chronic norovirus infection and common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol 2017; 188:363–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sacco KA, Pongdee T, Binnicker MJ, et al. Presence of immune deficiency increases the risk of hospitalization in patients with norovirus infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2018; 90:300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Angarone M, Ison MG. Diarrhea in solid organ transplant recipients. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2015; 28:308–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roos-Weil D, Ambert-Balay K, Lanternier F, et al. Impact of norovirus/sapovirus-related diarrhea in renal transplant recipients hospitalized for diarrhea. Transplantation 2011; 92:61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwartz S, Vergoulidou M, Schreier E, et al. Norovirus gastroenteritis causes severe and lethal complications after chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2011; 117:5850–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rossignol JF, El-Gohary YM. Nitazoxanide in the treatment of viral gastroenteritis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 24:1423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Todd KV, Tripp RA. Human norovirus: experimental models of infection. Viruses 2019; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chachu KA, Strong DW, LoBue AD, Wobus CE, Baric RS, Virgin HW 4th. Antibody is critical for the clearance of murine norovirus infection. J Virol 2008; 82:6610–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chachu KA, LoBue AD, Strong DW, Baric RS, Virgin HW. Immune mechanisms responsible for vaccination against and clearance of mucosal and lymphatic norovirus infection. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4:e1000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wingfield T, Gallimore CI, Xerry J, et al. Chronic norovirus infection in an HIV-positive patient with persistent diarrhoea: a novel cause. J Clin Virol 2010; 49:219–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Ravin SS, Wu X, Moir S, et al. Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8:335ra57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malm M, Tamminen K, Vesikari T, Blazevic V. Norovirus-specific memory T cell responses in adult human donors. Front Microbiol 2016; 7:1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malm M, Vesikari T, Blazevic V. Identification of a first human norovirus CD8+ T cell epitope restricted to HLA-A*0201 allele. Front Immunol 2018; 9:2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gerdemann U, Katari UL, Papadopoulou A, et al. Safety and clinical efficacy of rapidly-generated trivirus-directed T cells as treatment for adenovirus, EBV, and CMV infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Mol Ther 2013; 21:2113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leen AM, Myers GD, Sili U, et al. Monoculture-derived T lymphocytes specific for multiple viruses expand and produce clinically relevant effects in immunocompromised individuals. Nat Med 2006; 12:1160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Papadopoulou A, Gerdemann U, Katari UL, et al. Activity of broad-spectrum T cells as treatment for AdV, EBV, CMV, BKV, and HHV6 infections after HSCT. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:242ra83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leen AM, Bollard CM, Mendizabal AM, et al. Multicenter study of banked third-party virus-specific T cells to treat severe viral infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2013; 121:5113–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tzannou I, Papadopoulou A, Naik S, et al. Off-the-shelf virus-specific T cells to treat BK virus, human herpesvirus 6, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and adenovirus infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35:3547–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neuenhahn M, Albrecht J, Odendahl M, et al. Transfer of minimally manipulated CMV-specific T cells from stem cell or third-party donors to treat CMV infection after allo-HSCT. Leukemia 2017; 31:2161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muftuoglu M, Olson A, Marin D, et al. Allogeneic BK virus-specific T cells for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:1443–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Camargo JF, Wieder ED, Kimble E, et al. Deep functional immunophenotyping predicts risk of cytomegalovirus reactivation after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2019; 133:867–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rocha-Pereira J, Van Dycke J, Neyts J. Norovirus genetic diversity and evolution: implications for antiviral therapy. Curr Opin Virol 2016; 20:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turtle L, Bali T, Buxton G, et al. Human T cell responses to Japanese encephalitis virus in health and disease. J Exp Med 2016; 213:1331–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leen AM, Christin A, Khalil M, et al. Identification of hexon-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell epitopes for vaccine and immunotherapy. J Virol 2008; 82:546–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Withers B, Blyth E, Clancy LE, et al. Long-term control of recurrent or refractory viral infections after allogeneic HSCT with third-party virus-specific T cells. Blood Adv 2017; 1:2193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. LoBue AD, Lindesmith LC, Baric RS. Identification of cross-reactive norovirus CD4+ T cell epitopes. J Virol 2010; 84:8530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fritzlar S, Jegaskanda S, Aktepe TE, et al. Mouse norovirus infection reduces the surface expression of major histocompatibility complex class I proteins and inhibits CD8(+) T cell recognition and activation. J Virol 2018; 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gerdemann U, Keukens L, Keirnan JM, et al. Immunotherapeutic strategies to prevent and treat human herpesvirus 6 reactivation after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2013; 121:207–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Straathof KC, Leen AM, Buza EL, et al. Characterization of latent membrane protein 2 specificity in CTL lines from patients with EBV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma and lymphoma. J Immunol 2005; 175:4137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goldszmid RS, Dzutsev A, Trinchieri G. Host immune response to infection and cancer: unexpected commonalities. Cell Host Microbe 2014; 15:295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bull RA, Eden JS, Luciani F, McElroy K, Rawlinson WD, White PA. Contribution of intra- and interhost dynamics to norovirus evolution. J Virol 2012; 86:3219–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wen J, Tang WW, Sheets N, et al. Identification of Zika virus epitopes reveals immunodominant and protective roles for dengue virus cross-reactive CD8+ T cells. Nat Microbiol 2017; 2:17036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leen AM, Sili U, Vanin EF, et al. Conserved CTL epitopes on the adenovirus hexon protein expand subgroup cross-reactive and subgroup-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 2004; 104:2432–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.