Abstract

Background

The associations of density measures from the publicly available Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) software with breast cancer have primarily focused on estimates from the contralateral breast at the time of diagnosis.

Purpose

To evaluate LIBRA measures on mammograms obtained before breast cancer diagnosis and compare their performance to established density measures.

Materials and Methods

For this retrospective case-control study, full-field digital mammograms in for-processing (raw) and for-presentation (processed) formats were obtained (March 2008 to December 2011) in women who developed breast cancer an average of 2 years later and in age-matched control patients. LIBRA measures included absolute dense area and area percent density (PD) from both image formats. For comparison, dense area and PD were assessed by using the research software (Cumulus), and volumetric PD (VPD) and absolute dense volume were estimated with a commercially available software (Volpara). Density measures were compared by using Spearman correlation coefficients (r), and conditional logistic regression (odds ratios [ORs] and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) was performed to examine the associations of density measures with breast cancer by adjusting for age and body mass index.

Results

Evaluated were 437 women diagnosed with breast cancer (median age, 62 years ± 17 [standard deviation]) and 1225 matched control patients (median age, 61 years ± 16). LIBRA PD showed strong correlations with Cumulus PD (r = 0.77–0.84) and Volpara VPD (r = 0.85–0.90) (P < .001 for both). For LIBRA, the strongest breast cancer association was observed for PD from processed images (OR, 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1, 1.5), although the PD association from raw images was not significantly different (OR, 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1, 1.4; P = .25). Slightly stronger breast cancer associations were seen for Cumulus PD (OR, 1.5; 95% CI: 1.3, 1.8; processed images; P = .01) and Volpara VPD (OR, 1.4; 95% CI: 1.2, 1.7; raw images; P = .004) compared with LIBRA measures.

Conclusion

Automated density measures provided by the Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment from raw and processed mammograms correlated with established area and volumetric density measures and showed comparable breast cancer associations.

© RSNA, 2020

Summary

Automated measures by the Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment correlated with established area and volumetric density measures and showed comparable breast cancer associations on raw and processed mammograms.

Key Results

■ Automated percent density (PD) estimates from the Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) program from both for-processing (raw) and for-presentation (processed) formats were associated with breast cancer (odds ratio [OR], raw PD and processed PD: 1.2 and 1.3, respectively).

■ LIBRA density estimates were strongly correlated to commercial and research breast density programs, such as Volpara (r = 0.85–0.90) and Cumulus (r = 0.77–0.84) (P < .001 for both).

■ Stronger associations with breast cancer were observed for Cumulus PD (OR, 1.5; processed images) and Volpara density (OR, 1.4; raw images) compared with respective LIBRA PD measures (OR, processed and raw images: 1.3 [P = .01] and 1.2 [P = .004], respectively).

Introduction

Increased mammographic density has been shown consistently to be an independent risk factor for breast cancer (1–3) and a factor associated with decreased mammographic sensitivity because of masking of tumors within dense breast tissue (4–7). Several approaches have been developed to assess breast density in full-field digital mammography (FFDM) (8–13). The most commonly used method in the clinical setting is the visual grading of breast density by the interpreting radiologist into one of four categories outlined by the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, or BI-RADS (8). Initially the BI-RADS categories were based on approximate area percentage values of the dense tissue in relation to the whole breast area (fourth edition), whereas in the latest revision (fifth edition) there is more emphasis on the masking effect of dense tissue.

Semiautomated quantitative approaches such as the Cumulus software (version 4.2.1.0; Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto, Canada) (9,14) have been developed to provide finer area-based breast density measures. However, these approaches are subjective and time consuming and can result in substantial intra- and interobserver variability when not performed by experienced individuals (15). Fully automated algorithms have been developed to extract robust and reproducible quantitative measures of breast density (16). These include volumetric measures, which provide more accurate assessments of the volume (vs area) of dense tissue in the breast within programs such as Volpara (version 1.5.3; Volpara Health Technologies, Welllington, New Zealand) (12) and Quantra (Hologic, Marlborough, Mass) (13), which require the raw (ie, for processing) mammogram format for analysis.

The fully automated publicly available Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) software (version 1.0.4; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa, https://www.cbica.upenn.edu/sbia/software/LIBRA/) (11) is an area-based density assessment tool, which has been validated in several studies. LIBRA measures have shown positive associations with breast cancer (17–19), correlation with ethnicity (20), and other breast cancer risk factors (21) and have been shown to detect expected changes in density over time (22). In addition, LIBRA can assess density from both raw and processed (ie, for presentation) FFDM image formats. This is important because most clinical practices do not archive raw images because of cost and storage constraints, leaving only the processed FFDM image data available for retrospective analysis.

To our knowledge, associations of LIBRA measures with breast cancer have primarily focused on density estimates from the contralateral breast at the time of breast cancer diagnosis (17–19). In our study, we evaluated LIBRA density measures on mammograms years before the diagnosis of breast cancer. We also compared LIBRA to the Cumulus and Volpara density measures.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Acquisition

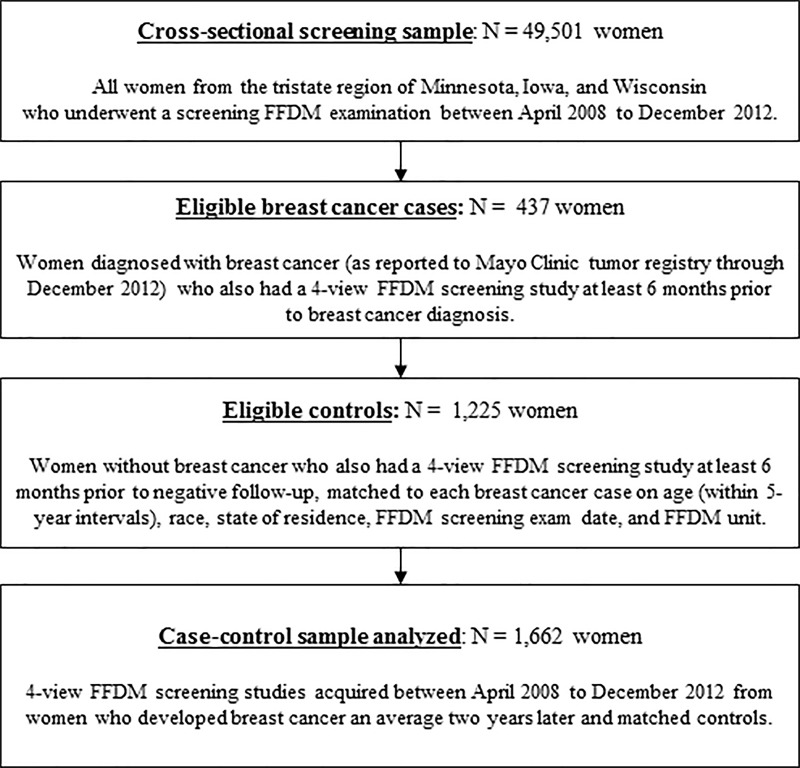

We analyzed FFDM images from a case-control sample nested within the breast screening practice at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minn; Fig 1) (23). From April 2008 through December 2012, there were 49 501 women from the tristate region of Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin who underwent an FFDM examination, which served as the underlying screening cohort. Eligible patients with breast cancer were women with incident breast cancers reported to the Mayo Clinic tumor registry through December 2012 (n = 437) occurring at least 6 months after mammography. Approximately three control patients (n = 1225) without previous breast cancer were matched to each breast cancer patient for age (within 5-year intervals), ethnicity, state of residence, FFDM screening examination date, and FFDM unit. Because of the retrospective nature of this study, a waiver of written informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization from the patients was approved by the institutional review board. However, we only included patients who had not refused permission to use their medical records for research (Minnesota Research Authorization), who composed over 95% of the practice (24).

Figure 1:

Flowchart shows criteria for case-control selection. FFDM = full-field digital mammography.

Clinical risk factor data and FFDM images acquired with Selenia (Hologic, Bedford, Mass) machines at least 6 months before the breast cancer diagnosis (or corresponding date for control patients) were ascertained. For the purposes of our study, all four views of the FFDM raw and processed imaging data were available for each woman and used to assess density.

Mammographic Breast Density Measures

LIBRA.—The fully automated, publicly available LIBRA software can be applied to both raw and processed FFDM images to generate area-based measurements of mammographic breast density (11). Briefly, LIBRA delineates the breast region by using edge-detection algorithms and applies fuzzy c-means clustering to partition the breast region into gray-level intensity clusters, which are then aggregated into the final dense tissue segmentation. By calculating the area of dense pixels, LIBRA provides an estimate of the total absolute dense area (DA), whereas normalizing DA by the total breast area results in breast percent density (PD). For this study, we used the DA and PD estimates obtained with LIBRA from all raw and processed images available for each woman.

Cumulus.—The semiautomated Cumulus (9,14) is a widely used research tool that requires trained observers to segment the breast area from background and then set window levels and thresholds for each image to segment dense breast tissue from nondense tissue for analysis. In this study, Cumulus breast density assessment was performed on processed FFDM images only because previous work has shown strong correlations and similar associations with breast cancer when Cumulus density was assessed on raw and processed images from the same women (17,25). Cumulus readings of DA and PD from processed images were performed independently for each woman over a 3-month period (November 2017 to February 2018) by a single reader with over 20 years of experience estimating density with Cumulus (F.F.W.). The reader was blinded to cancer status.

Volpara.—The fully automated Volpara software estimates volumetric measures from raw FFDM images only (12). Volpara uses a proprietary algorithm to measure breast thickness and x-ray attenuations on the raw image and create estimates of dense and nondense tissue volume for each pixel. Summing the dense pixel volumes provides total absolute dense volume, whereas normalizing absolute dense volume by the total breast volume defines volumetric PD (VPD). Absolute dense volume and VPD from all raw images available for each woman were used.

Statistical Analysis

Density measures were averaged from all four mammographic views. Correlations between density measures were evaluated with Wilcoxon signed rank tests and Spearman correlation coefficients separately for patients with breast cancer and control patients. Conditional logistic regression was used to evaluate the association of density measures with breast cancer, adjusting for age and body mass index. Density measures were transformed as needed to achieve normality: natural logarithm (LIBRA and Volpara) or square root (Cumulus). The results of logistic regression analyses were summarized in odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) per standard deviation (SD) of the density measures (by using the control population). Our sample size provided 80% power to detect an OD as low as 1.18 per one SD in density measure, assuming a type 1 error rate of 0.05. The case-control discriminatory ability of models was summarized by using the c-statistic calculated within matched sets. To compare ORs and c-statistics across different density measures, 1000 bootstrap samples were chosen at random while maintaining the matched sets, and P values were calculated on the basis of the comparisons across these 1000 samples. Statistical software (SAS version 9.4; SAS, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses, and P values of .05 or less were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The study sample was composed of 437 women diagnosed with breast cancer (median age, 62 years; interquartile range, 54–71 years) and 1225 matched control patients (median age, 61 years; interquartile range, 54–70 years). There were no differences in age (P = .64), body mass index (P = .81), and ethnicity (P = .20) distributions for patients with breast cancer and control patients (Table 1). There was an average of 2.1 years between the FFDM screening examination used for breast density assessment and either the breast cancer diagnosis date (patients with breast cancer) or follow-up (control patients).

Table 1:

Breast Cancer Risk Factors and Demographic Characteristics by Case-control Status

Comparisons between Mammographic Breast Density Assessment Methods

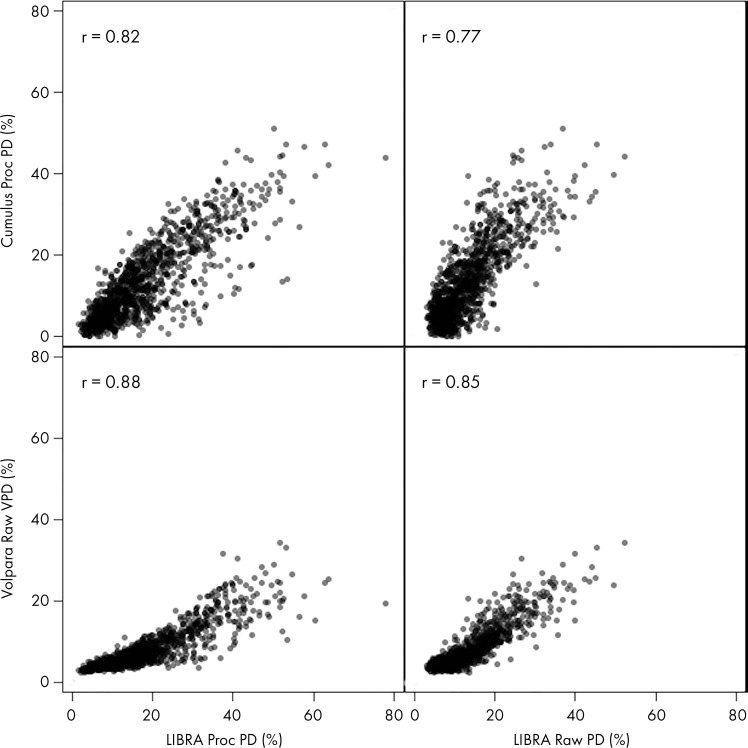

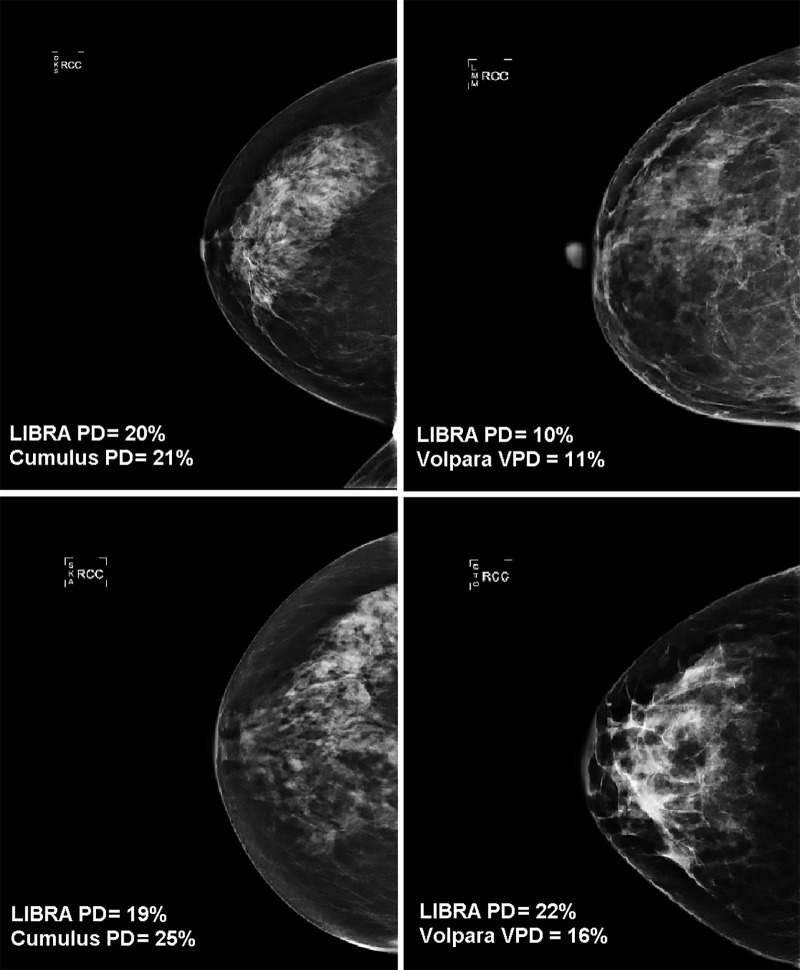

PD estimates on processed images were higher for LIBRA than for Cumulus (patients with breast cancer: median, 16.8% vs 12.5%, respectively [P < .001]; control patients: median, 14.9% vs 10.6%, respectively [P < .001]) (Figs 2, E1 [online]; Table 2). In addition, on raw mammograms, LIBRA yielded higher estimates of PD relative to Volpara VPD (patients with breast cancer: median, 11.4% vs 6.5%, respectively [P < .001]; control patients: median, 10.8% vs 5.8%, respectively [P < .001]). Figure 3 illustrates high and low agreement of LIBRA PD with Cumulus PD and with Volpara VPD.

Figure 2:

Correlations of Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA), Cumulus, and Volpara percent density (PD) measures in control patients. Top row is processed (proc) images; bottom row is raw images. VPD = volumetric PD.

Table 2:

Breast Density Distributions and Associations with Breast Cancer

Figure 3:

Examples of full-field digital mammographic images with high (top) and low (bottom) agreement of Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) percent density (PD) with Cumulus PD on processed images (left side) and with Volpara volumetric PD (VPD) on raw images (right side).

LIBRA PD extracted from either raw or processed images was highly correlated with Cumulus (r = 0.77–0.84; P < .001) and Volpara PD measures (r = 0.85–0.90; P < .001) for both patients with breast cancer and control patients (Figs 2, E1 [online]). Weaker correlations were observed for LIBRA absolute density measures, including LIBRA DA with Cumulus DA (r = 0.57–0.73; P < .001) and LIBRA DA with Volpara absolute dense volume (r = 0.48–0.68; P < .001) (Figs E2, E3 [online]).

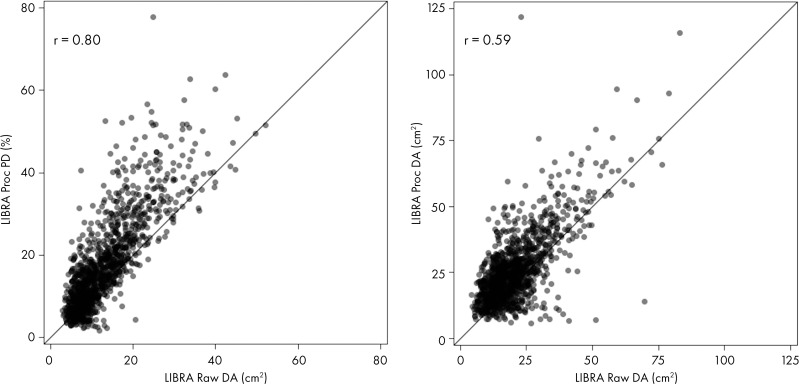

Correlations among LIBRA measures from raw and processed images were also stronger for PD (r = 0.80–0.82; P < .001) compared with DA (r = 0.59–0.61; P < .001) (Figs 4, E4 [online]).

Figure 4:

Correlations of Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) density measures extracted from raw and processed image formats in control patients. The left panel shows percent density (PD) and the right panel shows dense area (DA). Proc = processed.

Association of Breast Density with Breast Cancer

After adjusting for age and body mass index, there were positive associations of all density measures with breast cancer, with ORs ranging from 1.1 to 1.5 (Table 2). LIBRA PD measures on raw images had a weaker association with breast cancer than Volpara (OR, 1.2 per SD of LIBRA PD [95% CI: 1.1, 1.4] vs 1.4 per SD of Volpara VPD [95% CI: 1.2, 1.7], respectively; P = .004). LIBRA PD from processed mammograms had a weaker association with breast cancer than Cumulus (OR, 1.3 per SD LIBRA PD [95% CI: 1.1, 1.5] vs 1.5 per SD Cumulus PD [95% CI: 1.3, 1.8], respectively; P = .01). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the associations of absolute dense tissue measures with breast cancer for LIBRA compared with Volpara and Cumulus (P > .05). Moreover, all models showed nonstatistically significant differences in discriminatory capacities (P > .05) for all three breast density assessment methods that ranged from c-statistic of 0.55 to 0.59 (Table 2).

There were no differences between the associations of LIBRA PD measures obtained from either raw versus processed FFDM images with breast cancer (OR, 1.2 per SD of LIBRA raw PD [95% CI: 1.1, 1.4] vs 1.3 per SD of LIBRA processed PD [95% CI: 1.1, 1.5]; P = .25). There were also no differences for the associations of LIBRA absolute dense tissue measures with breast cancer by image type (OR, 1.1 per SD of LIBRA raw DA [95% CI: 1.0, 1.3] vs 1.2 per SD of LIBRA processed DA [95% CI: 1.1, 1.4]; P = .14).

Discussion

Our study validated the association of the publicly available fully automated Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) density measures with breast cancer. Previous case-control studies (17–19) evaluated LIBRA on full-field digital mammographic (FFDM) images at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. In our study, we evaluated LIBRA breast density measures on FFDM images obtained before a diagnosis of breast cancer. Our results demonstrated that LIBRA measures from both raw and processed FFDM formats were associated with the subsequent development of breast cancer (odds ratio [OR], 1.2–1.3 per standard deviation of LIBRA percent density [PD]). Moreover, a comprehensive comparison of LIBRA PD with the widely-used Cumulus and Volpara methods for density assessments showed that density measures by all three methods were strongly correlated (r = 0.77–0.90; P < .001). LIBRA produced slightly weaker associations of PD with breast cancer than did PD measures from Cumulus (OR, 1.5; processed images) and Volpara (OR, 1.4; raw images); however, the differences in risk did not translate to differences in discriminatory accuracy.

Unlike the semiautomated area-based Cumulus that requires interaction with a trained user, which is both time consuming and variable among different readers, LIBRA provides rapid, fully automated, and highly reproducible quantitative density measures. Additionally, unlike the commercial Volpara software that can only be applied to raw mammography, the publicly available LIBRA is also able to estimate density on processed FFDM images. These advantages may facilitate retrospective research studies because most clinical settings only save processed images because of cost and space constraints. Finally, LIBRA is free to download. However, we recognize LIBRA provides measures that are based on the two-dimensional projection of the three-dimensional dense tissue volume and may not capture the volume of dense tissue.

Our findings showed weaker LIBRA density associations with breast cancer than previous reports. For instance, in a study from the United States with raw FFDM images in 106 patients with breast cancer and 318 control patients (mean age, 55.1 years; interquartile range, 48–61 years; ethnicity: 57% white, 22% African American, 3% Asian, and 18% other/unknown), Keller et al (18) reported stronger associations between breast cancer and LIBRA PD and DA (OR, 2.6 per SD of PD [95% CI: 1.8, 3.9] and 2.6 per SD increase in DA [95% CI: 1.9, 3.6]). Higher ORs were also reported in a more recent Korean study (19) that evaluated LIBRA in 398 patients with breast cancer and 737 control patients (mean age, 49 years ± 6 [SD]), wherein LIBRA DA demonstrated an OR of 1.7 (95% CI: 1.4, 2.2). Differences may be because of different demographic characteristics of our data set or timing of acquisition of FFDM images relative to breast cancer diagnosis. Both studies evaluated mammography at the time of diagnosis, which generally showed stronger associations of breast density with breast cancer compared with studies that evaluated mammography before diagnosis (6). Nevertheless, our findings are consistent in that LIBRA is a valid fully automated alternative for breast density assessment that can be applied on both raw and clinically available processed images.

Processed mammographic images are generated after manufacturer-specific postprocessing algorithms are applied to raw images, with the goal of adjusting the image contrast to increase lesion conspicuity. Our findings suggested that manufacturer-specific postprocessing algorithms have minor effects on LIBRA breast density assessment. Consistent with previous work (17,26), LIBRA density measures extracted from both processed and raw images were highly correlated. Moreover, LIBRA density measures from the two FFDM formats demonstrated comparable capacities in breast cancer risk prediction.

The strengths of our study include the availability of both FFDM formats taken from the same women at the same point, which allowed us to compare LIBRA measures from both FFDM image formats and the comparisons of LIBRA with the other widely used breast density assessment methods, Cumulus and Volpara. Moreover, we assessed images before a diagnosis of breast cancer, critical for evaluating markers for breast cancer risk prediction.

Our study had limitations. The limitations included the ethnically homogeneous composition and the moderate sample size of our study population, although we were powered to detect the associations seen in our study. Further work is warranted to validate our findings across larger, more diverse populations. Future evaluation of LIBRA will also include density measures assessed at least 5 years before breast cancer diagnosis, allowing for greater use in risk prediction (27). Furthermore, we aim to also look into comparisons with more refined, localized breast parenchymal complexity features that are complementary to the amount of dense tissue in the breast and are provided by emerging radiomic and deep learning methods (28–30).

Our results extend previous studies demonstrating that fully automated area percent density measures obtained with the publicly available Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) software from full-field digital mammographic images can predict breast cancer. Therefore, LIBRA may be a viable alternative to expensive commercially available software for breast density evaluation. Moreover, because LIBRA uses processed images stored by all breast imaging practices, LIBRA assessments may help accelerate additional validation of breast density as a clinically important predictor of breast cancer in large multisite imaging populations.

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Mayo patients who provided research authorization that allows access to medical records, including images, and provides the opportunity to conduct retrospective studies of this nature. We also acknowledge Katelyn Cordie, BS, for her administrative assistance with the submission of this manuscript.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: A.G. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.D.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.G.S. disclosed no relevant relationships. K.R.B. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.R.J. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.B.H. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money paid to author for royalties from CMR Naviscan. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. F.F.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. A.D.N. disclosed no relevant relationships. E.F.C. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money to author’s institution for consultancy from Hologic and iCAD; disclosed money to author’s institution for grants/grants pending from Hologic and iCAD. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. S.J.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. K.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.M.V. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money to author’s institution from Grail for conducting a clinical observational trial of a liquid biopsy; disclosed money from grants from National Cancer Institute; disclosed travel/accommodations/meeting expenses from Grail. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R01 research projects [2R01CA161749-05, R01CA207369, and R01CA177150] and a resource-related research project cooperative agreement [1U24CA189523-01A1]). A.G. supported in part by the Susan G. Komen for the Cure Breast Cancer Foundation (PDF17479714).

Abbreviations:

- CI

- confidence interval

- DA

- dense area

- FFDM

- full-field digital mammography

- LIBRA

- Laboratory for Individualized Breast Radiodensity Assessment

- OR

- odds ratio

- PD

- percent density

- SD

- standard deviation

- VPD

- volumetric percent density

References

- 1.Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Bronskill M, Yaffe MJ, Duric N, Minkin S. Breast tissue composition and susceptibility to breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102(16):1224–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15(6):1159–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brentnall AR, Cuzick J, Buist DSM, Bowles EJA. Long-term accuracy of breast cancer risk assessment combining classic risk factors and breast density. JAMA Oncol 2018;4(9):e180174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandelson MT, Oestreicher N, Porter PL, et al. Breast density as a predictor of mammographic detection: comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92(13):1081–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E, et al. Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2005;353(17):1773–1783 [Published correction appears in N Engl J Med 2006;355(17):1840.]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;356(3):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Are You Dense Advocacy . D.E.N.S.E. State Efforts. http://areyoudenseadvocacy.org/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

- 8.D’Orsi CJ. ACR BI-RADS Atlas: Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, Va: American College of Radiology, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byng JW, Boyd NF, Fishell E, Jong RA, Yaffe MJ. The quantitative analysis of mammographic densities. Phys Med Biol 1994;39(10):1629–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damases CN, Brennan PC, Mello-Thoms C, McEntee MF. Mammographic Breast Density Assessment Using Automated Volumetric Software and Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) Categorization by Expert Radiologists. Acad Radiol 2016;23(1):70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller BM, Nathan DL, Wang Y, et al. Estimation of breast percent density in raw and processed full field digital mammography images via adaptive fuzzy c-means clustering and support vector machine segmentation. Med Phys 2012;39(8):4903–4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Highnam R, Brady M, Yaffe MJ, Karssemeijer N, Harvey J. Robust Breast Composition Measurement-VolparaTM. In: Martí J, Oliver A, Freixenet J, Martí R, eds. Digital Mammography. IWDM 2010. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 6136. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2010; 342–349. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartman K, Highnam R, Warren R, Jackson V. Volumetric Assessment of Breast Tissue Composition from FFDM Images. In: Krupinski EA, ed. Digital Mammography. IWDM 2008. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 5116. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2008; 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, et al. Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87(9):670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller BM, Nathan DL, Gavenonis SC, Chen J, Conant EF, Kontos D. Reader variability in breast density estimation from full-field digital mammograms: the effect of image postprocessing on relative and absolute measures. Acad Radiol 2013;20(5):560–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conant EF, Sprague BL, Kontos D. Beyond BI-RADS Density: A Call for Quantification in the Breast Imaging Clinic. Radiology 2018;286(2):401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busana MC, Eng A, Denholm R, et al. Impact of type of full-field digital image on mammographic density assessment and breast cancer risk estimation: a case-control study. Breast Cancer Res 2016;18(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller BM, Chen J, Daye D, Conant EF, Kontos D. Preliminary evaluation of the publicly available Laboratory for Breast Radiodensity Assessment (LIBRA) software tool: comparison of fully automated area and volumetric density measures in a case-control study with digital mammography. Breast Cancer Res 2015;17(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen TL, Choi Y-H, Aung YK, et al. Breast cancer risk associations with digital mammographic density by pixel brightness threshold and mammographic system. Radiology 2018;286(2):433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy AM, Keller BM, Pantalone LM, et al. Racial Differences in Quantitative Measures of Area and Volumetric Breast Density. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108(10):djw104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albeshan SM, Hossain SZ, Mackey MG, Peat JK, Al Tahan FM, Brennan PC. Preliminary investigation of mammographic density among women in Riyadh: association with breast cancer risk factors and implications for screening practices. Clin Imaging 2019;54:138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams AD, So A, Synnestvedt M, et al. Mammographic breast density decreases after bariatric surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;165(3):565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandt KR, Scott CG, Ma L, et al. Comparison of Clinical and Automated Breast Density Measurements: Implications for Risk Prediction and Supplemental Screening. Radiology 2016;279(3):710–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41(6):1614–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vachon CM, Fowler EE, Tiffenberg G, et al. Comparison of percent density from raw and processed full-field digital mammography data. Breast Cancer Res 2013;15(1):R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gastounioti A, Oustimov A, Keller BM, et al. Breast parenchymal patterns in processed versus raw digital mammograms: A large population study toward assessing differences in quantitative measures across image representations. Med Phys 2016;43(11):5862–5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerlikowske K, Scott CG, Mahmoudzadeh AP, et al. Automated and Clinical Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System Density Measures Predict Risk for Screen-Detected and Interval Cancers: A Case-Control Study. Ann Intern Med 2018;168(11):757–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kontos D, Winham SJ, Oustimov A, et al. Radiomic Phenotypes of Mammographic Parenchymal Complexity: Toward Augmenting Breast Density in Breast Cancer Risk Assessment. Radiology 2019;290(1):41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yala A, Lehman C, Schuster T, Portnoi T, Barzilay R. A Deep Learning Mammography-based Model for Improved Breast Cancer Risk Prediction. Radiology 2019;292(1):60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dembrower K, Liu Y, Azizpour H, et al. Comparison of a Deep Learning Risk Score and Standard Mammographic Density Score for Breast Cancer Risk Prediction. Radiology 2020;294(2):265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.