Abstract

Collectively, viruses are the principal cause of cancers arising in patients with immune dysfunction, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patients. Kaposi sarcoma (KS) etiologically linked to Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) continues to be the most common AIDS-associated tumor. The involvement of the oral cavity represents one of the most common clinical manifestations of this tumor. HIV infection incurs an increased risk among individuals with periodontal diseases and oral carriage of a variety of pathogenic bacteria. However, whether interactions involving periodontal bacteria and oncogenic viruses in the local environment facilitate replication or maintenance of these viruses in the oral cavity of HIV-positive patients remain largely unknown. We previously showed that pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from specific periodontal bacteria promoted KSHV entry into oral cells and subsequent establishment of latency. In the current study, we demonstrate that Staphylococcus aureus, one of common pathogens causing infection in HIV-positive patients, and its PAMPs can effectively induce KSHV lytic reactivation from infected oral cells, through the Toll-like receptor reactive oxygen species and cyclin D1-Dicer-viral microRNA axis. This investigation provides further clinical evidence about the relevance of coinfection due to these 2 pathogens in the oral cavities of a cohort HIV-positive patients and reveals novel mechanisms through which these coinfecting pathogens potentially promote virus-associated cancer development in the unique niche of immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: KSHV, Kaposi sarcoma, HIV, Staphylococcus aureus, microRNA

This study summarizes the clinical prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus coinfection with Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patients and reveals the mechanisms by which S. aureus/KSHV coinfection potentially promotes HIV-associated cancer development.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Little and Uldrick, on pages 1226–8.)

Infection with Kaposi sarcoma (KS)–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and subsequent development of its principal clinical consequence, KS, occur with greater frequency following human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or organ transplantation [1]. Despite the reduced incidence of KS in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) for HIV infection [2], KS remains the most common AIDS-associated tumor and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in this setting [3, 4]. Moreover, KS is increasingly recognized in individuals with well-controlled HIV infection [5, 6]. The World Health Organization has declared KS one of the “cardinal” oral lesions associated with HIV infection in the modern era [7]. The existing clinical data suggest that KSHV dissemination within and from the oral cavity are critical factors for KSHV infection and oral KS progression in HIV-positive patients [8, 9]. Although cART and immune recovery result in reduction of KSHV viremia levels in a subset of patients, cART does not reduce KSHV replication in the oropharynx or KSHV transmission [8, 9]. Interestingly, one recent study of herpesvirus oral shedding in HIV-infected patients indicated that KSHV is similarly detectable across all CD4+ T-cell counts [10]. In addition, oral cavity involvement represents the initial manifestation of KS in 20%–60% of HIV-associated cases [11, 12]. Oral KS lesions contain higher KSHV loads relative to skin KS lesions and may portend a higher mortality rate for HIV-positive patients [13].

Periodontitis is characterized by chronic inflammation associated with oral bacteria and fungi, resulting in destruction of periodontal ligaments and the supporting bone of the tooth, ultimately leading to significant morbidity, high cost of oral health care, and tooth loss [14]. Several studies indicate a significantly higher prevalence of severe oral inflammation and periodontal disease for HIV-positive patients [15, 16]. The pathogenesis of periodontitis and associated chronic oral inflammation is dependent on the local microbiome within the gingival sulcus, whereas some pathogens associated with periodontitis, such as Staphylococcus aureus, a representative gram-positive species, have been found more commonly in patients with HIV infection [17]. Published data indicate that bacteria and viruses in the oral cavity interact to facilitate periodontal disease [18], and inflammatory factors associated with periodontitis have been associated with KS progression [19].

Bacterial species can produce various pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are recognized by pathogen-recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and induce host cell innate immune responses [20]. We recently reported that pretreatment of primary human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament fibroblasts with a prototypical PAMP, lipoteichoic acid from S. aureus, increased KSHV entry and subsequent expression of genes responsible for viral latency [21]. The underlying mechanisms include upregulation of cellular receptors for KSHV entry (particularly heparan sulfate proteoglycan), increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a cofactor facilitating virus entry, and activation of intracellular signaling pathways, including MAPK and NF-κB, both of which are required for establishment of KSHV latency [21]. However, establishment of latency in oral cells is not sufficient to initiate KS development, as the virus must be reactivated for lytic replication and then spread in the oral cavity. Therefore, in the current study, we focused on understanding whether and how S. aureus and its components affect KSHV lytic reactivation from oral cells and the clinical prevalence and relevance of their coinfection in oral cavities of HIV-positive patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture, Bacteria Strains, Reagents, and Infection Protocols

The KSHV-positive PEL cell line BCBL-1 was kindly provided by Dr Dean Kedes (University of Virginia) and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02% (wt/vol) sodium bicarbonate. Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and cultured in F-12K medium with supplements as recommended by the manufacturer. Primary human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament fibroblasts were purchased from ScienCell and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B. S. aureus strains 8325-4, MN8, MN8 (SarAYFP), and MN8 (AgrYFP) were kindly provided by Dr Liang Yang (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) and grown in tryptic soy broth. S. aureus lipoteichoic acid was purchased from InvivoGen, and the purity was >99.5%. To obtain KSHV for infection experiments, BCBL-1 cells were incubated with 0.6 mM valproic acid for 4–6 days, and KSHV was purified from culture supernatants by ultracentrifugation at 20 000 × g for 3 hours at 4°C. The viral pellets were resuspended in 1/100th the original volume in the appropriate culture medium. The infectious titers were determined as described previously [22].

Patients and Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research (approval no. 8079) at Louisiana State University Health Science Center. All subjects provided written informed consent. A total of 53 HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) in our HIV outpatient clinic were involved. There were 21 women and 32 men, with an average age of 49.8 years (range, 21–67 years). The average CD4+ T-cell count was 607 cells/mL (range, 31–1903 cells/mL), and the average HIV load was 6044 copies/mL (range, 24–67 082 copies/mL).

Preparation of Plasma and Saliva Specimens

Whole-blood specimens were collected in heparin-coated tubes, and plasma was isolated by centrifugation. KSHV infection status was determined by quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for identifying circulating immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to KSHV proteins (LANA and K8.1) [23, 24]. To collect whole-saliva specimens, patients rinsed with mouthwash, and saliva specimens were collected in a wide-mouthed 50-mL Nalgene tube. Typical volumes ranged from 3 to 5 mL of mouthwash. The patients were asked not to eat or smoke before providing the samples. Saliva specimens from 19 dental patients who tested negative for HIV and KSHV infection were used as a comparison.

Cell Viability and Cell Cycle Analyses

Cell viability was measured using WST-1 assays (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell pellets were fixed in 70% ethanol, incubated at 4°C overnight, resuspended in 0.5 mL of 0.05 mg/mL proprium iodide plus 0.2 mg/mL RNase A, and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The cell cycle distribution was analyzed on a FACS Calibur 4-color flow cytometer (BD Bioscience).

Biochemical Assays

Intracellular ROS levels were measured using the ROS dye c-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen) as described previously [21]. Total levels of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in saliva samples were determined using the OxiSelect In Vitro ROS/RNS assay kit (Cell Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The total concentrations of lipoteichoic acid and uric acid and the peroxidase activity in saliva specimens were quantified using a lipoteichoic acid ELISA kit (Novatein Bioscience), a uric acid assay kit, and a peroxidase activity assay kit (Sigma), respectively. The chemiluminescence-based NADPH oxidase activity assays were performed as described previously [21].

RNA Interference (RNAi) Assays and Quantitative Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Analyses

For RNAi assays, TLR2 or TLR4 On-Target plus Smart pool small interfering RNA (siRNA; Dharmacon) or negative control siRNA were delivered using the DharmaFECT transfection reagent. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), and complementary DNA was synthesized using a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix kit (Invitrogen). Primers used for amplification of target genes are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Amplification was performed using an iCycler IQ Real-Time PCR detection system, and cycle threshold (Ct) values were tabulated in duplicate for each gene of interest in each experiment. No-template (ie, water) controls were used to ensure minimal background contamination. Using mean Ct values tabulated for each gene and paired Ct values for the gene encoding β-actin as a loading control, fold changes for experimental groups relative to assigned controls were calculated using automated iQ5 2.0 software (Bio-Rad). For amplification of viral microRNAs (miRNAs), complementary DNA was synthesized using the Taqman miRNA RT kit, and qPCR was performed using the Taqman miRNA assay kit (Applied Biosystems). Fold changes for miRNA were calculated using paired Ct values for RNU6B. When PCR was used to detect bacteria and viruses in saliva samples, the positive (ie, S. aureus 8325-4 DNA or KSHV-positive BCBL-1 DNA) and negative (ie, water) template controls were used, too.

Immunoblotting

Total cell lysates (30 µg) were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with 100–200 µg/mL of antibodies for cyclin D1, Dicer, Ago1/2, Drosha, Rac1, and IKKε (Cell Signaling); Nox1 (Abcam); and p22phox, NFIB, Rbl2, TLR2, and TLR4 (Santa Cruz).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of differences between experimental and control groups was determined using the 2-tailed Student t test (Excel 8.0), and P values <.05 or <.01 were considered significant or highly significant, respectively.

RESULTS

TLR2-Mediated ROS Production and Signaling Is Required for Induction of KSHV Lytic Reactivation From Infected Oral Cells by S. aureus Culture and Components

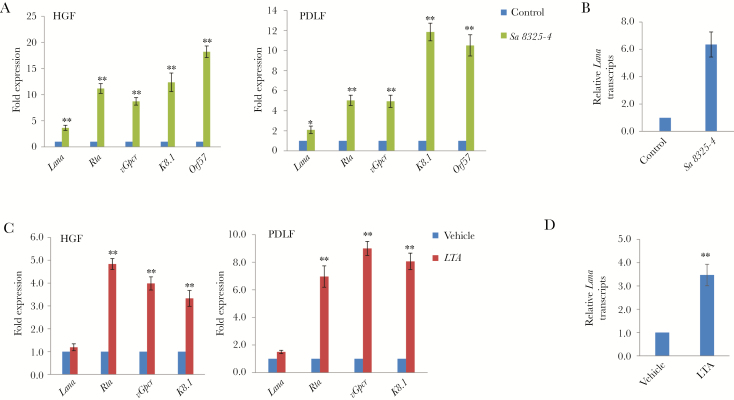

We first found that treating latently infected primary human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament fibroblasts with filtered conditioned medium from S. aureus strain 8325-4 induced significantly higher expression of KSHV lytic genes, including Rta, vGpcr, K8.1, and Orf57, compared with cells treated with fresh medium (Figure 1A). We next found that S. aureus–conditioned medium induced release of infectious virion particles from these oral cells, as demonstrated by increased expression of the KSHV gene Lana in naive oral fibroblasts following their incubation with supernatants collected from KSHV-positive oral fibroblasts treated with S. aureus–conditioned medium (Figure 1B). Moreover, these effects were also observed in oral cells infected with virus and treated with S. aureus–derived lipoteichoic acid (Figure 1C and 1D). However, we did not observe similar effects using conditioned medium or purified lipoteichoic acid from other gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis (data not shown), indicating a specificity for bacterial species.

Figure 1.

Induction of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) lytic reactivation by Staphylococcus aureus–conditioned medium and/or S. aureus–derived lipoteichoic acid (LTA). A, Oral fibroblasts were infected by purified KSHV (multiplicity of infection [MOI], approximately 10) for 2 hours. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with filtered conditioned medium from overnight S. aureus strain 8325-4 culture or fresh medium control (diluted as 1:50) for an additional 48 hours. Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis was used to quantify the expression of representative viral latency (Lana) and lytic genes (Rta, vGpcr, K8.1, and Orf57). B and D, Conditioned medium from periodontal ligament fibroblasts (PDLFs) in panels A or C were collected, ultracentrifuged, and resuspended to infect fresh PDLFs. Lana transcripts (reflecting the level of infectious particles released) were measured by qRT-PCR. C, Cells were infected as described in panel A and then incubated with S. aureus–derived LTA (5.0 µg/mL) for 48 hours, followed by qRT-PCR analysis. Error bars represent the SD for 3 independent experiments. HGF, human gingival fibroblast. *P < .05 and **P < .01, by a 2-tailed Student t test.

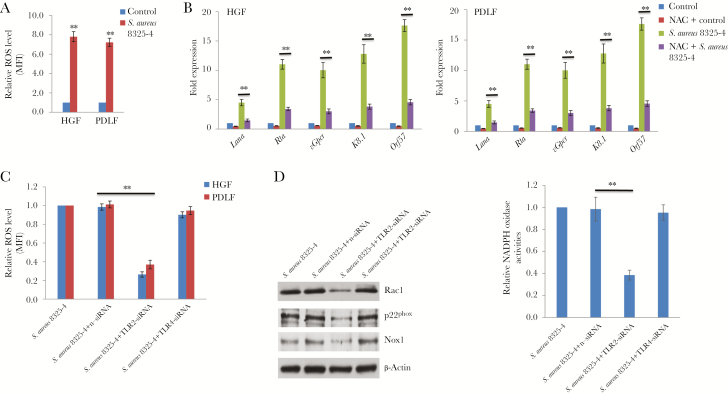

As mentioned above, our recent data indicated that periodontal bacterial PAMPs (eg, S. aureus–derived lipoteichoic acid) increased KSHV entry and expression of latency-associated viral genes in oral cells by inducing intracellular ROS production [21]. Here, we found that S. aureus–conditioned medium treatment also induced intracellular ROS production from latently infected oral fibroblasts (Figure 2A). Furthermore, pretreatment with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) effectively blocked viral lytic gene expression in cells exposed to S. aureus–conditioned medium (Figure 2B). Since TLRs are closely associated with mediating the effects of bacterial PAMPs (eg, lipoteichoic acid or lipopolysaccharide binding to TLR2 or TLR4, respectively), we first assessed TLR2 and TLR4 expression in oral cells, using human monocyte THP-1 and primary HUVECs as a comparison. Our data confirmed that both TLR2 and TLR4 are expressed in oral fibroblasts (Supplementary Figure 1A). Silencing of TLR2 (but not TLR4) by RNAi effectively reduced ROS production from KSHV-infected oral cells exposed to S. aureus–conditioned medium (Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure 1B). Cellular ROS production usually requires the NADPH oxidase complex, which comprises various NADPH oxidases and cytosolic components, depending on the stimulus and cell type [25]. Here, we demonstrated that silencing of TLR2 (but not TLR4) by RNAi mainly downregulated the expression of NADPH oxidase, Nox1, and other cytosolic components, such as Rac1 and p22phox, from oral fibroblasts (Figure 2D). Using a biochemical assay described previously [21], we confirmed that silencing of TLR2 significantly reduced NADPH oxidase activity in oral cells exposed to S. aureus–conditioned medium (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)–mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and signaling is required for induction of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) lytic reactivation by Staphylococcus aureus–conditioned medium. A, Oral fibroblasts were infected by purified KSHV (multiplicity of infection [MOI], approximately 10) for 2 hours. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with filtered conditioned medium from S. aureus 8325-4 culture or fresh medium as a control (diluted as 1:50) for an additional 48 hours. Intracellular levels of ROS were quantified using the ROS-specific dye CM-H2DCFDA and flow cytometry. B, Cells were infected as described in panel A and then were or were not treated with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC; 1 mM) for an additional 24 hours. Cells were then incubated with S. aureus–conditioned medium or control for 48 hours, followed by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis. C, Cells were infected as described in panel A. Twenty-four hours later, cells were transfected with either negative control small interfering RNA (n-siRNA), TLR2 siRNA, or TLR4 siRNA for 48 hours and then treated with filtered conditioned medium from S. aureus 8325-4 culture (diluted 1:50) for an additional 48 hours. Intracellular levels of ROS were quantified as described above. D, Human gingival fibroblasts (HGFs) were treated as described in panel C, protein expression was detected by immunoblots, and NADPH oxidase activities were measured using a chemiluminescence-based assay as described in “Methods.” Error bars represent the SD for 3 independent experiments. MFI, median fluorescence intensity; PDLF, periodontal ligament fibroblast. **P < .01, by a 2-tailed Student t test.

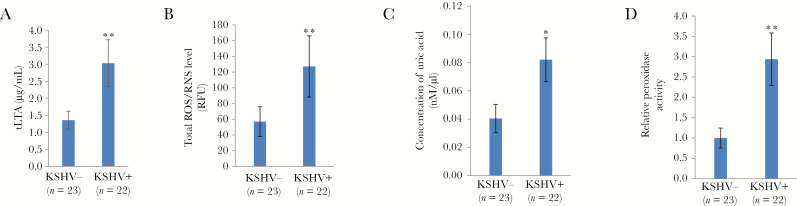

Clinical Relevance of Bacterial PAMPs and Host Salivary Antioxidant Factors Among HIV-Positive Patients With or Without KSHV Coinfection

It is important to determine the clinical relevance of those microenvironmental factors derived from host and periodontal pathogens, their interactions, and their contribution to oral KSHV pathogenesis and tumorigenesis in HIV-positive patients. Our data indicated that patients positive for both HIV and KSHV had higher levels of total salivary lipoteichoic acid than HIV-positive, KSHV-negative patients, indicating the potential clinical implication of periodontal bacterial PAMPs in oral KSHV pathogenesis and disease progression (Figure 3A). Currently, there are no commercial kits available to measure the lipoteichoic acid concentration derived from a single bacterial species; therefore, we can only measure total lipoteichoic acid levels. Recent studies indicated a correlation between the salivary ROS level and the severity of periodontal disease [26]. Our data indicated that, among HIV-positive patients, the KSHV-positive group had higher salivary ROS/RNS levels than the KSHV-negative group (Figure 3B). Furthermore, saliva specimens from HIV-positive patients with KSHV coinfection possessed higher concentrations or activities of host antioxidant factors [27], including uric acid and peroxidase (Figure 3C, D). Together, these data indicate that these periodontal bacterial components and the host ROS system are potentially connected to oral KSHV pathogenesis in HIV-positive patients.

Figure 3.

Higher levels of salivary bacterial pathogen–associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), reactive oxygen species (ROS)/reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and host antioxidant factors are present in patients positive for both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV). A and B, The salivary total lipoteichoic acid (tLTA; A) and ROS/RNS (B) levels in HIV-positive patients were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described in “Methods.” C and D, Levels of the host antioxidant factor uric acid (C) and peroxidase activity (D) were measured using the commercial kits as described in “Methods.” Error bars represent the SD for 3 independent experiments. RFU, relative fluorescence units; −, negative; +, positive. *P < .05 and **P < .01, by a 2-tailed Student t test.

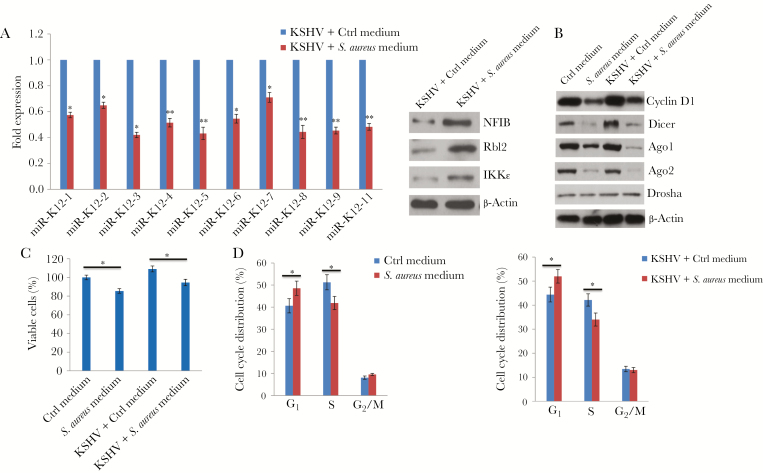

Induction of KSHV Lytic Reactivation From Infected Oral Cells During S. aureus Culture Is Regulated Through the Cyclin D1-Dicer-Viral miRNA Axis

KSHV encodes 12 pre-miRNAs, which are processed into 25 mature miRNAs [28]. Interestingly, KSHV miRNAs are clustered in the latency locus of the viral genome. Of the 12 pre-miRNAs, 10 (miR-K12 1–9 and 11) are located in the sequence between the genes encoding Kaposin and ORF71, whereas miR-K12 10 is located in the gene encoding Kaposin, with miR-K12-12 mapped to the 3′ untranslated region [28]. Not surprisingly, most KSHV miRNAs maintain viral latency in host cells through either direct targeting of the viral lytic reactivation activator, Rta, or indirect mechanisms, including by targeting several host factors [29]. Our data showed that the expression of clustered KSHV miRNAs, including miR-K12 1–9 and 11, were all downregulated in virally infected oral cells treated with S. aureus 8325-4–conditioned medium, compared with controls treated with fresh medium (Figure 4A). Moreover, we found that treating cells with S. aureus–conditioned medium increased expression of the host proteins NFIB, Rbl2, and IKKɛ, which have been experimentally validated as direct targets of miR-K12 3, 4, and 11, respectively [30–32] (Figure 4A). Currently, the regulatory mechanisms of KSHV miRNA processing and expression remain largely unknown, although one recent study reported that latent KSHV infection increased expression of Dicer, one of the important components for miRNA synthesis [33]. Another recent study revealed a novel mechanism whereby cyclin D1 induction of Dicer coordinates cellular miRNA biogenesis in breast cancer cells [34]. We found that treatment with S. aureus–conditioned medium significantly reduced the expression of cyclin D1 and other host proteins responsible for cellular miRNA processing, including Dicer, Argonaute 1, and Argonaute 2 but not Drosha, in oral cells regardless of KSHV infection (Figure 4B). Consistent with the function of cyclin D1 as an important cell cycle checkpoint regulator, we found that treating oral cells with S. aureus–conditioned medium reduced cell viability and caused cell cycle arrest (mostly at G1 phase) regardless of KSHV infection status (Figure 4C and 4D).

Figure 4.

Cyclin D1–mediated downregulation of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) microRNA (miR) expression from infected oral cells by Staphylococcus aureus–conditioned medium. A, Human gingival fibroblasts (HGFs) were infected by purified KSHV (multiplicity of infection [MOI], approximately 10) for 2 hours. Twenty-four hours later, cells were incubated with S. aureus 8325-4–conditioned medium (1:50 dilution) or control medium (Ctrl) for 48 hours, followed by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction for KSHV miRNA quantification. Protein expression was measured by immunoblots. B–D, Cells were infected with or without purified KSHV (MOI, approximately10) for 2 hours. Twenty-four hours later, cells were incubated with S. aureus 8325-4–conditioned medium (1:50 dilution) or Ctrl for 48 hours. Protein expression, cell viability, and cell cycle distribution were measured using immunoblots, WST-1 assays, and flow cytometry, respectively. Error bars represent the SD for 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 and **P < .01, by a 2-tailed Student t test.

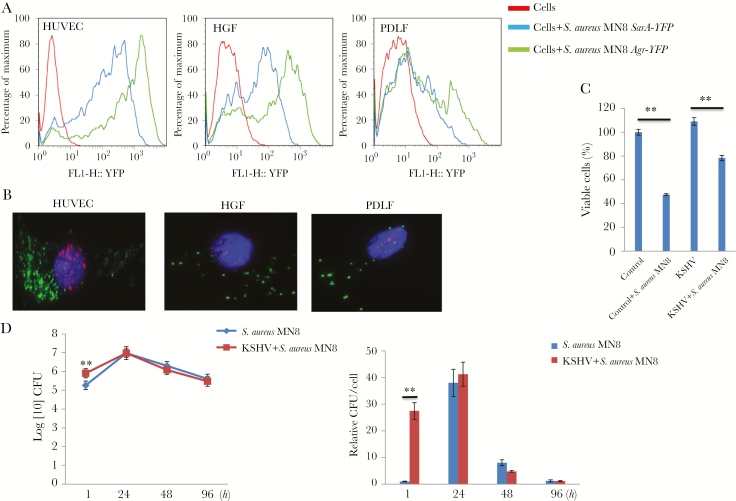

S. aureus and KSHV Coinfection in Human Primary Cells

In addition to conditioned medium or purified bacterial components, we also explored whether S. aureus and KSHV can coinfect a primary cell. S. aureus invades, internalizes in, and survives in a variety of host cells, including fibroblasts and endothelial cells [35, 36], which represent the major components of KS lesions. Here, we demonstrated the successful internalization of S. aureus in human primary cells, including HUVECs and oral fibroblasts, using the YFP-labeled bacterial strains and flow cytometry (Figure 5A), although HUVECs were more accessible to S. aureus internalization and survival than oral fibroblasts. Importantly, our immunofluorescence results confirmed coinfection with S. aureus and KSHV within the same single cell (Figure 5B). S. aureus infection reduced the viability of oral cells regardless of KSHV infection status (Figure 5C) and induced viral lytic gene expression from infected cells (Figure S2), although KSHV-infected cells showed increased resistance to S. aureus–induced inhibition of cell growth. Interestingly, KSHV-infected cells showed greatly increased S. aureus internalization at very early time points (eg, 1 hour) after bacterial infection than noninfected cells (8.5 × 105 vs 1.8 × 105 colony-forming units; Figure 5D), implying potential interaction between these 2 pathogens within host cells.

Figure 5.

Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus and coinfection with Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) in human primary cells. A, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and oral fibroblasts were grown as monolayers in 24-well tissue culture plates and then infected by S. aureus strain MN8 (containing S. aureus major virulence genes SarA or Agr labeled with the YFP reporter in their promoters) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 100 for 1 hour. The cells were washed and treated with lysostaphin (10 µg/mL) for 20 minutes to lyse extracellular bacteria prior to lifting with trypsin. The intracellular YFP signal was detected by flow cytometry, and uninfected cells served as the negative control. B, Cells were first infected by purified KSHV (MOI, approximately 10) for 2 hours. A total of 24 hours later, cells were infected with S. aureus strain MN8 (Agr-YFP). After incubation for an additional 72 hours, immunofluorescence was performed for detection of LANA (representing latently infected KSHV; red) and YFP (representing internalized S. aureus; green), and nuclei were identified by DAPI staining (blue). C, Human gingival fibroblasts (HGFs) were first infected by purified KSHV (MOI, approximately 10) for 2 hours. Twenty-four hours later, cells were infected with S. aureus strain MN8. After additional incubation for 48 hours, cell viability was measured using the WST-1 assay. D, HUVECs with or without KSHV infection were infected with S. aureus strain MN8. The numbers of internalized bacteria at different time points after infection were determined by measuring colony counts on a tryptic soy broth plate. Error bars represent the SD for 2 independent experiments. CFU, colony-forming units; PDLF, periodontal ligament fibroblast. **P < .01, by a 2-tailed Student t test.

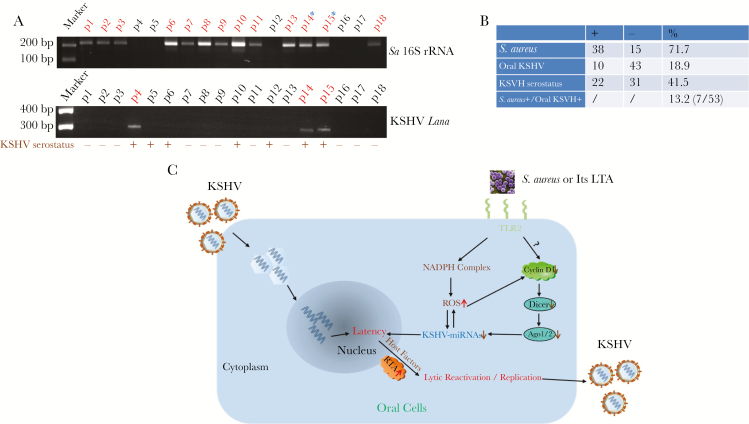

Clinical Prevalence of S. aureus and KSHV Shedding in the Oral Cavity of HIV-Positive Patients

Evaluation of saliva samples obtained from HIV-positive patients revealed that 71.7% (38 of 53) were positive for S. aureus and 18.9% (10 of 53) were positive for KSHV LANA (a viral protein marker representing latent infection; Figure 6A and 6B). Notably, 7 patients (13.2%) were positive for both S. aureus and KSHV, providing clinical evidence of coinfection by a specific periodontal bacterial species and oncogenic virus in the oral cavity of HIV-positive patients. By comparison, there was a lower prevalence of S. aureus carriage (36.8% [7 of 19 patients]) in the group negative for both HIV and KSHV (data not shown). We noticed that 37.7% of HIV-positive patients (20 of 53) were KSHV seropositive, which is higher than the prevalence determined by analyzing their saliva samples (18.9%), probably because of the difficulty in acquiring KSHV-infected oral cells during collection of saliva specimens.

Figure 6.

Clinical prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) shedding within saliva samples from cohort human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patients. A, Total DNA was extracted from saliva samples of cohort HIV-positive patients, using the QIAamp DNA mini-kit (Qiagen). Then, polymerase chain reaction analysis was performed using specific primers designed for the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) of S. aureus or the KSHV-encoded major latency gene Lana. Amplicons were subsequently identified by ethidium bromide–loaded agarose gel electrophoresis; representative bands are shown. Asterisks represent double-positive patients. The KSHV seroprevalence was determined using quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) as described in “Methods.” B, Results for samples from 53 HIV-positive patients are shown. C, A hypothetical model of the mechanisms through which S. aureus coinfection induces KSHV lytic reactivation and replication from latently infected oral cells. Ago, Argonaute; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; ROS, reactive oxygen species; −, negative; +, positive.

Discussion

Published studies suggest that unique interactions between KSHV and the oral microenvironment may facilitate KSHV dissemination and contribute to oral KS progression, despite appropriate therapy for HIV infection. In the current study, we provide solid evidence that S. aureus coinfection involving whole live bacteria, conditioned medium, and purified PAMPs can effectively induce viral lytic reactivation from oral cells (Figure 6C). As a consequence, these events should facilitate KSHV dissemination in the oral cavity of HIV-positive patients. Although a small proportion of infected cells undergo lytic reactivation in KS tissues, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated that expression of lytic proteins contributes substantially to KSHV-associated oncogenesis [19, 37]. Consistent with the high prevalence of HIV infection and HIV-associated cancers in Louisiana (and in New Orleans in particular) as compared to the United States as a whole, our data showed a much higher rate of S. aureus carriage in saliva samples from HIV-positive patients, compared with that for HIV-negative patients (71.7% vs 36.8%). Even for patients with saliva specimens negative for S. aureus, we cannot exclude the possibility of S. aureus infection at other body sites, since S. aureus ranks among the most common causes of bacterial infections in HIV-positive patients [38]. S. aureus has been shown to colonize the anterior nares of HIV-positive patients with greater frequency than in the general population [39]. Moreover, concordant with the emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the community setting, colonization and infection with MRSA have become prevalent problems in the HIV-positive population [40, 41]. Our findings suggest that S. aureus may produce/release extracellular factors, including PAMPs, that induce KSHV lytic reactivation, which means that the oral cavity may not be the primary infection site (eg, infection may occur at sites such as the face, nose, or laryngopharynx).

Our previous and current data demonstrate that ROS and related signaling are involved in KSHV entry, latency establishment, and lytic reactivation from oral cells, indicating that ROS may play a central role in KSHV-associated pathogenesis. Recently, ROS was identified as a cofactor for KSHV entry [42] and for facilitating KSHV lytic reactivation [43]. The small GTPase Rac1 is an inflammatory signaling mediator triggering ROS production by NADPH oxidases. Recently, Rac1 transgenic mice were created to display KS-like tumors that arise from mechanisms involving ROS-driven proliferation, upregulation of AKT signaling, and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α–related angiogenesis [44]. Interestingly, our additional data showed that blocking ROS by NAC reversed S. aureus–conditioned medium mediated repression of multiple KSHV miRNAs from infected oral cells (Supplementary Figure 3), although the mechanisms remain unclear. Recent studies reported the reduction of cyclin D1 expression by inducing ROS production from cancer cells [45, 46]. Combined with our results, it is reasonable to speculate that there is cross-talk between ROS signaling and the cyclin D1-Dicer-viral miRNA axis. In addition, a recent study reported that short-chain fatty acids produced by periodontal bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum induced KSHV lytic reactivation through suppression of histone deacetylases and histone N-lysine methyltransferases [47]. S. aureus–conditioned medium contains a variety of bioactive molecules, so it will be interesting to determine which other molecules in conditioned medium contribute to induce virus lytic reactivation.

We found that KSHV infection greatly increased S. aureus internalization at a very early time point after bacterial infection. These findings raise some questions, such as whether increasing S. aureus internalization is likely to promote new KS formation or whether S. aureus is more likely to become a strong cofactor once KS lesions are established. The recently established KS mouse model [48] can be used to address the first question. For the latter question, to our knowledge there are no published results describing the presence of specific periodontal bacterial carriage within oral KS lesions. Previous studies provided evidence for S. aureus carriage within oral epithelial cells and/or oral tissues, using fluorescence in situ hybridization assays [49]. Cutaneous and mucosal KS has a typical progression, beginning with an early patch and progressing to an intermediate plaque, followed by formation of tumor nodules [50]. Using immunohistochemical staining, we demonstrated that advanced cutaneous KS lesions have higher nuclear KSHV LANA expression (or viral loads) [22]. Therefore, it would be interesting to know whether oral KS tissues may have the same pattern and, if so, whether these are related to S. aureus carriage within tumor tissues. Taken together, our results suggest that antistaphylococcal strategies may have preventive or therapeutic potential for treating KS in patients with AIDS.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Disclaimer. Funding sources had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant 1R01CA228166-01), the Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute (Seeds of Science Pilot Award), FY19 UAMS Chancellor’s Award, and the Arkansas Bioscience Institute (the major research component of the Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Proceeds Act of 2000).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, Martin J, Bower M, Whitby D. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vanni T, Sprinz E, Machado MW, Santana Rde C, Fonseca BA, Schwartsmann G. Systemic treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma: current status and perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev 2006; 32:445–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Engels EA, Biggar RJ, Hall HI, et al. Cancer risk in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Int J Cancer 2008; 123:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonnet F, Lewden C, May T, et al. Malignancy-related causes of death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer 2004; 101:317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maurer T, Ponte M, Leslie K. HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma with a high CD4 count and a low viral load. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1352–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krown SE, Lee JY, Dittmer DP, Consortium AM. More on HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:535–6; author reply 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coogan MM, Greenspan J, Challacombe SJ. Oral lesions in infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83:700–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Casper C, Redman M, Huang ML, et al. HIV infection and human herpesvirus-8 oral shedding among men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004; 35:233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miller CS, Berger JR, Mootoor Y, Avdiushko SA, Zhu H, Kryscio RJ. High prevalence of multiple human herpesviruses in saliva from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:2409–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dittmer DP, Tamburro K, Chen H, et al. Oral shedding of herpesviruses in HIV-infected patients with varying degrees of immune status. AIDS 2017; 31:2077–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pak F, Pyakural P, Kokhaei P, et al. HHV-8/KSHV during the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma: evaluation by polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol 2005; 32:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lager I, Altini M, Coleman H, Ali H. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study from South Africa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003; 96:701–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rohrmus B, Thoma-Greber EM, Bogner JR, Röcken M. Outlook in oral and cutaneous Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet 2000; 356:2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Griffen AL, Beall CJ, Campbell JH, et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. ISME J 2012; 6:1176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phiri R, Feller L, Blignaut E. The severity, extent and recurrence of necrotizing periodontal disease in relation to HIV status and CD4+ T cell count. J Int Acad Periodontol 2010; 12:98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mataftsi M, Skoura L, Sakellari D. HIV infection and periodontal diseases: an overview of the post-HAART era. Oral Dis 2011; 17:13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakou M, Kamma J, Gargalianos P, Laskaris G, Mitsis F. Periodontal microflora of HIV infected patients with periodontitis. Anaerobe 1997; 3:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Slots J. Human viruses in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2010; 53:89–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer 2010; 10:707–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hernández M, Dutzan N, García-Sesnich J, et al. Host-pathogen interactions in progressive chronic periodontitis. J Dent Res 2011; 90:1164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dai L, DeFee MR, Cao Y, et al. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from periodontal pathogenic bacteria facilitate oncogenic herpesvirus infection within primary oral cells. PLoS One 2014; 9:e101326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qin Z, Freitas E, Sullivan R, et al. Upregulation of xCT by KSHV-encoded microRNAs facilitates KSHV dissemination and persistence in an environment of oxidative stress. PLoS Pathog 2010; 6:e1000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mbisa GL, Miley W, Gamache CJ, et al. Detection of antibodies to Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: a new approach using K8.1 ELISA and a newly developed recombinant LANA ELISA. J Immunol Methods 2010; 356:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Benavente Y, Mbisa G, Labo N, et al. Antibodies against lytic and latent Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus antigens and lymphoma in the European EpiLymph case-control study. Br J Cancer 2011; 105:1768–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2007; 87:245–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoshino F, Yoshida A, Wada-Takahashi S, et al. Assessments of salivary antioxidant activity using electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Arch Oral Biol 2012; 57:654–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagler RM, Klein I, Zarzhevsky N, Drigues N, Reznick AZ. Characterization of the differentiated antioxidant profile of human saliva. Free Radic Biol Med 2002; 32:268–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qin J, Li W, Gao SJ, Lu C. KSHV microRNAs: tricks of the devil. Trends Microbiol 2017; 25:648–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Qin Z, Jakymiw A, Findlay V, Parsons C. KSHV-encoded MicroRNAs: lessons for viral cancer pathogenesis and emerging concepts. Int J Cell Biol 2012; 2012:603961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bellare P, Ganem D. Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell Host Microbe 2009; 6:570–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lei X, Bai Z, Ye F, et al. Regulation of NF-kappaB inhibitor IkappaBalpha and viral replication by a KSHV microRNA. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liang D, Gao Y, Lin X, et al. A human herpesvirus miRNA attenuates interferon signaling and contributes to maintenance of viral latency by targeting IKKε. Cell Res 2011; 21:793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Happel C, Ramalingam D, Ziegelbauer JM. Virus-mediated alterations in miRNA factors and degradation of viral miRNAs by MCPIP1. PLoS Biol 2016; 14:e2000998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu Z, Wang L, Wang C, et al. Cyclin D1 induction of Dicer governs microRNA processing and expression in breast cancer. Nat Commun 2013; 4:2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Usui A, Murai M, Seki K, Sakurada J, Masuda S. Conspicuous ingestion of Staphylococcus aureus organisms by murine fibroblasts in vitro. Microbiol Immunol 1992; 36:545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hirschhausen N, Schlesier T, Schmidt MA, Götz F, Peters G, Heilmann C. A novel staphylococcal internalization mechanism involves the major autolysin Atl and heat shock cognate protein Hsc70 as host cell receptor. Cell Microbiol 2010; 12:1746–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cavallin LE, Goldschmidt-Clermont P, Mesri EA. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of KSHV oncogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma associated with HIV/AIDS. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1004154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Senthilkumar A, Kumar S, Sheagren JN. Increased incidence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in hospitalized patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:1412–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weinke T, Schiller R, Fehrenbach FJ, Pohle HD. Association between Staphylococcus aureus nasopharyngeal colonization and septicemia in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1992; 11:985–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hidron AI, Kempker R, Moanna A, Rimland D. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in HIV-infected patients. Infect Drug Resist 2010; 3:73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sabbagh P, Riahi SM, Gamble HR, Rostami A. The global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in HIV-infected people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control 2019; 47:323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bottero V, Chakraborty S, Chandran B. Reactive oxygen species are induced by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus early during primary infection of endothelial cells to promote virus entry. J Virol 2013; 87:1733–49.23175375 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li X, Feng J, Sun R. Oxidative stress induces reactivation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and death of primary effusion lymphoma cells. J Virol 2011; 85:715–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ma Q, Cavallin LE, Yan B, et al. Antitumorigenesis of antioxidants in a transgenic Rac1 model of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:8683–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shi Y, Bollam SR, White SM, et al. Rac1-mediated DNA damage and inflammation promote Nf2 tumorigenesis but also limit cell-cycle progression. Dev Cell 2016; 39:452–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li C, Peng W, Song X, Wang Q, Wang W. Anticancer effect of icaritin inhibits cell growth of colon cancer through reactive oxygen species, Bcl-2 and cyclin D1/E signaling. Oncol Lett 2016; 12:3537–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu X, Shahir AM, Sha J, et al. Short-chain fatty acids from periodontal pathogens suppress histone deacetylases, EZH2, and SUV39H1 to promote Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication. J Virol 2014; 88:4466–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dai L, Del Valle L, Miley W, et al. Transactivation of human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) by KSHV promotes Kaposi’s sarcoma development. Oncogene 2018; 37:4534–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Colombo AV, Barbosa GM, Higashi D, di Micheli G, Rodrigues PH, Simionato MR. Quantitative detection of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in human oral epithelial cells from subjects with periodontitis and periodontal health. J Med Microbiol 2013; 62:1592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Antman K, Chang Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1027–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.