Abstract

Background

The ubiquitous human pathogens, herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 and HSV-2, are distinct viral species that diverged approximately 6 million years ago. At least 4 small, ancient HSV-1 × HSV-2 interspecies recombination events have affected the HSV-2 genome, with recombinants and nonrecombinants at each locus circulating today. However, it is unknown whether interspecies recombination can affect other loci and whether new recombinants continue to be generated.

Methods

Using 255 newly sequenced and 230 existing HSV genome sequences, we comprehensively assessed interspecies recombination in HSV.

Results

Our findings show that the sizes and locations of interspecies recombination events in HSV-2 are significantly more variable than previously appreciated and that they can impact species-specific T-cell recognition of HSV.

Conclusions

We describe 2 large (>5 kb) recombination events, one of which arose in its current host, demonstrating that interspecies recombination continues to occur today. These results raise concerns about the use of live-attenuated HSV-2 vaccines in high HSV-1 prevalence areas.

Keywords: genome, herpes simplex virus, phylogeny, recombination, T-cells

A comprehensive survey of approximately 500 HSV genomes reveals HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination events up to 7 kilobases in length at loci across the HSV-2 genome and demonstrates that novel interspecies recombinants continue to be generated.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Scott Schmid, on pages 1208–9.)

The herpes simplex viruses (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are ubiquitous human pathogens with 3.7 billion HSV-1 and 417 million HSV-2 infected persons worldwide [1, 2]. Both viruses establish lifelong infections typically characterized by mild, intermittent symptoms. However, HSV can cause significant morbidity and mortality, particularly among the immunocompromised and in neonates [3, 4]. Genital HSV-2 infection also substantially increases the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition [5–7]. Although antivirals can reduce symptoms, they neither cure infection nor prevent viral shedding and transmission, leading to the urgent need for an HSV vaccine [8].

Instrumental in the development of an HSV vaccine and of new pharmaceutical therapies for HSV is a better understanding of the evolution of HSV and of genetic variation among viral strains. Herpes simplex virus-1 and HSV-2 diverged from one another approximately 6 million years ago, after which HSV-1 evolved in the human lineage and HSV-2 in the chimpanzee lineage [9]. A human ancestor then acquired HSV-2 as a zoonotic infection from a chimpanzee ancestor 1.4–3 million years ago [9]. Early studies of HSV genomes indicated that the viral species were relatively homogenous (mean pairwise distances among HSV-1 and HSV-2 strains are 0.8% and 0.2%, respectively) [10]. However, in 2015, an HSV-2 strain was described that was highly divergent from other HSV-2 samples at a single genomic locus [11]. This divergent region was likely affected by an ancient HSV-1 × HSV-2 interspecies recombination event with both recombinant and nonrecombinant genotypes at this locus observed among HSV-2 strains today [12, 13]. Ultimately, 4 loci, totaling approximately 1% of the HSV-2 genome, were found that carried evidence of such recombination events [12, 13]. Recombinant genotypes are found at high frequencies for 3 of these loci, subgenic regions within the UL29, UL30, and UL39 genes. Only 1 HSV-2 sample has been found that carries HSV-1 sequence at the fourth locus within UL15.

The high degree of divergence between recombinant and nonrecombinant HSV-2 strains at these loci makes interspecies recombination a major source of variation among HSV-2 strains. However, numerous questions remain about the role of interspecies recombination in the evolution of HSV-2. In particular, it remains unknown whether interspecies recombination can affect loci other than those previously described in UL15, UL29, UL30, and UL39 and whether interspecies recombinants continue to be generated because all events described to date are thought to have occurred in a historical context. We sought to answer these questions by performing a survey of interspecies recombination on a large dataset of HSV genome sequences comprising both previously available and newly generated sequences.

METHODS

Samples

All samples were collected from 1994 to 2016 as part of clinical research studies on HSV infection at the University of Washington (UW) Virology Research Clinic (for Seattle samples) or at international study sites in Cameroon, Peru, Senegal, and Uganda (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Oral and genital swabs were either self-collected by participants or collected by clinicians. Swabs were collected from genital lesions or as mixed anogenital samples [14]. Written informed consent to collect swabs and demographic information was obtained from all participants. Studies were approved by the UW Human Subjects Division (Institutional Review Board Numbers: STUDY00001279, STUDY00000408) and the local institutional review boards/ethics committees for the international sites.

Most sequenced samples had HSV viral loads greater than 1000 copies/mL due to limitations in recovering sequences from samples with lower viral copy numbers [15]. We otherwise selected samples from our repository for sequencing based on geographic origin, collection date, and presence of HSV-2 superinfection or HSV-1/HSV-2 genital coinfection (Supplementary Methods).

Sequencing and Consensus Generation

We used a previously described next-generation, direct-capture sequencing method for HSV [15]. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted directly from sample swabs. Pooled DNA from multiple samples was then sequenced after enrichment using HSV-1- and HSV-2-specific oligonucleotide capture panels.

Consensus sequences and .bam files were created from raw sequencing reads using a previously described computational pipeline [15], which is publicly available at https://github.com/proychou/HSV/. For HSV-1, strain 17 (NC_001806.1) was used as the reference [16]. For HSV-2, SD90e (KF781518.1) was used as the reference [17]. Sequences were named using the alphaherpesvirus method previously proposed [18] (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Phylogenetic Trees

Newly sequenced and publicly available HSV-1 and HSV-2 genomes downloaded from GenBank and EMBL (Supplementary Methods) were aligned using MAFFT [19]. The terminal and internal repeat regions and intragenic regions were removed from these alignments, leaving concatenated UL-US coding sequences. These alignments were used to generate the trees in Figure 1. For Figures 2 and 3, regions of interest as described in the text were extracted from alignments to create each tree. The phylogenetic trees in Figures 2C and 3C were created using MrBayes [20] and those in Figures 1A and B, 2D, and 3D were created with PHYML (Supplementary Methods) [21]. PHYML was used in place of MrBayes for the latter trees given the prolonged run times required by MrBayes for alignments of long sequences. For trees constructed from alignments of relatively short sequences (Figures 2C and 3C), sequences with any missing data (Ns) were excluded. For all other trees, sequences with greater than 10% missing data (Ns) were excluded.

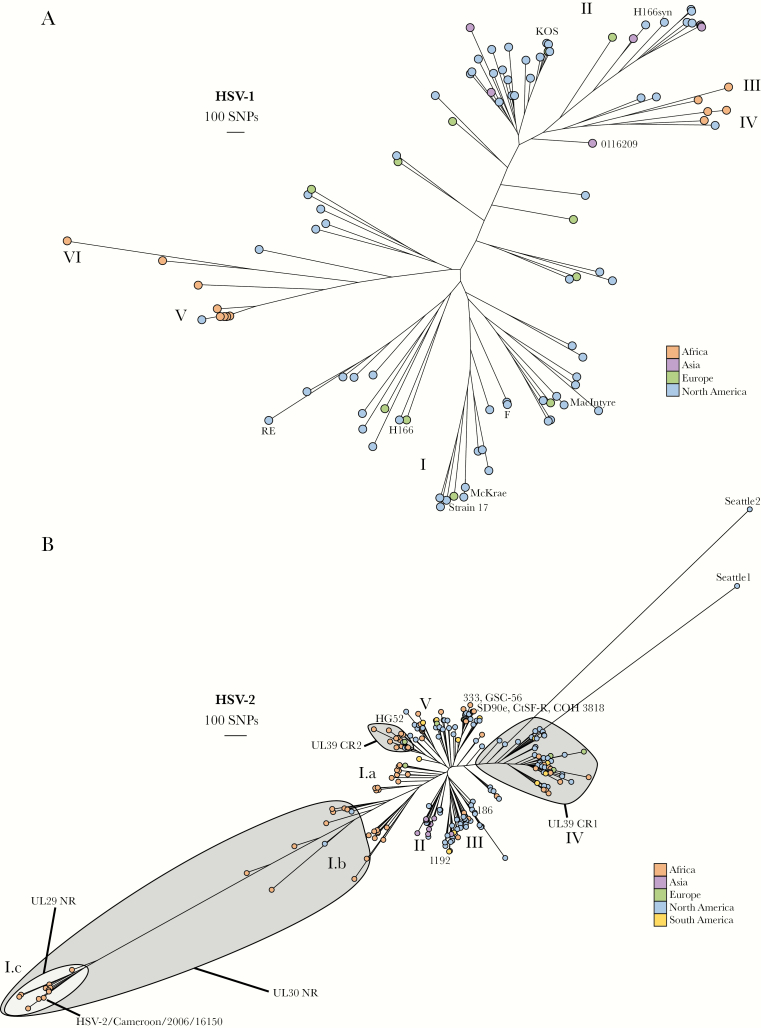

Figure 1.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 and HSV-2 phylogenetic trees. (A) Phylogenetic tree of all available HSV-1 genomes (only 1 genome included per person) color-coded by geographic origin. The strain names for some genomes are included next to their location in the tree for reference. Clades I–VI are labeled. (B) Phylogenetic tree of all available HSV-2 genomes (only 1 genome included per person) color-coded by geographic origin. The strain names for some genomes are included next to their location in the tree for reference. Clades I–V are labeled as are clusters defined by UL29, UL30, and UL39 genotype.

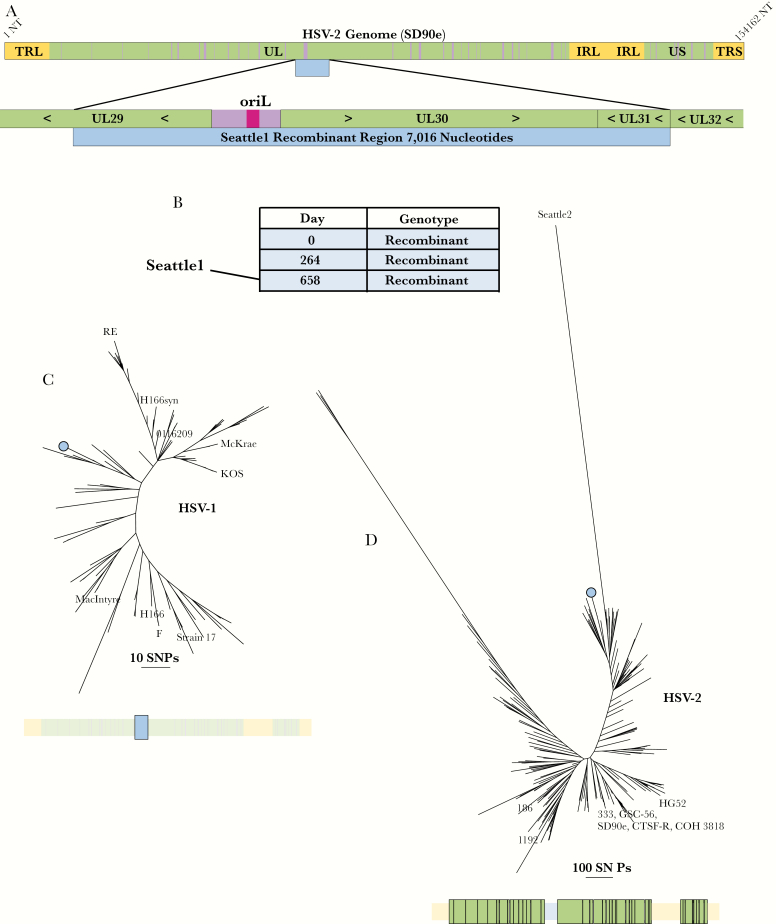

Figure 2.

Seattle1 (UL29–UL31) recombinant. (A) Schematic showing the size and position of the recombination event relative to the herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2 genome and within its genic neighborhood. Green represents coding regions and purple represents noncoding regions. The recombinant region is represented by a blue bar. (B) List of all sequenced samples collected from the person carrying the Seattle1 (UL29–UL31) recombinant with the day of sample collection relative to the collection date of the first sample. (C) Phylogenetic tree of the recombinant region extracted from HSV-1 sequences and from the Seattle1 (UL29–UL31) recombinant. The bar below the tree shows the extracted region (colored in bright blue and enlarged) relative to the rest of the genome (faded out). The branch representing the UL29–UL31 recombinants is marked with blue circle. (D) Phylogenetic tree of HSV-2 genomes without UL29, UL30, and UL31. The bar below the tree shows the extracted regions (colored in bright green and enlarged) relative to the rest of the genome (faded out). All 3 HSV-2 sequences from the person carrying the Seattle1 (UL29–UL31) recombinant clustered on the branch marked with the blue circle.

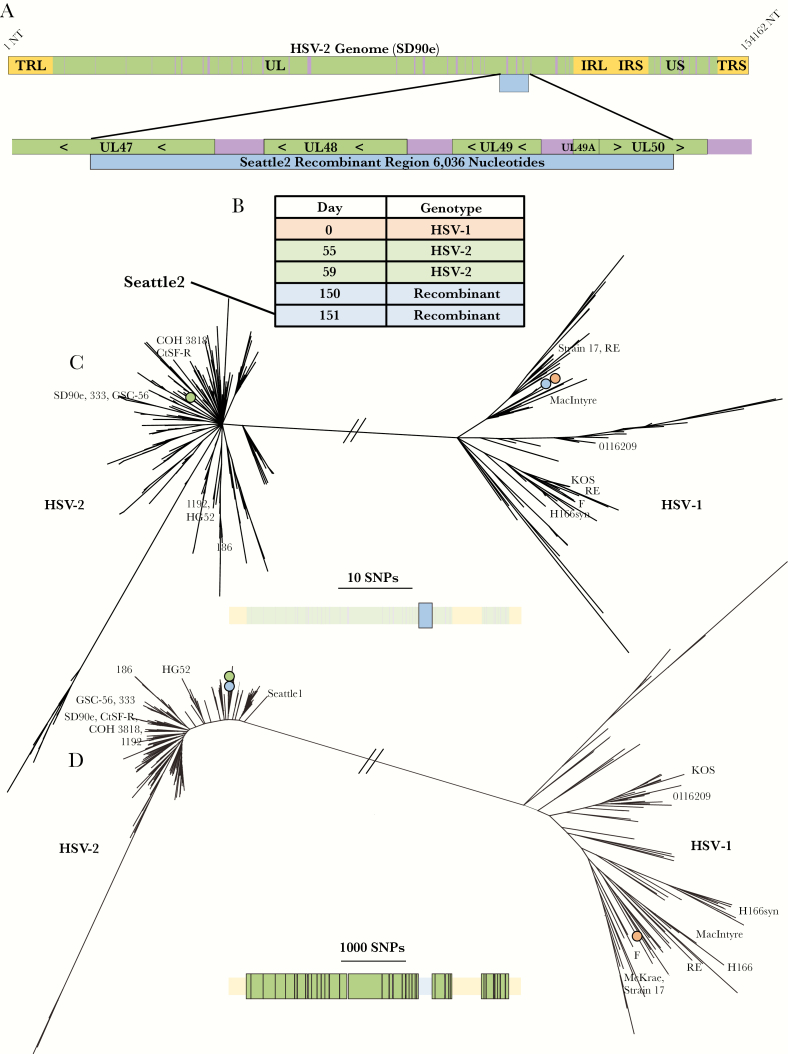

Figure 3.

Seattle2 (UL47–UL50) recombinant. (A) Schematic showing the size and position of the recombination event relative to the herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2 genome and within its genic neighborhood. Green represents coding regions and purple represents noncoding regions. The recombinant region is represented by a blue bar. (B) List of all sequenced samples collected from the person carrying the Seattle2 (UL47–UL50) recombinant with the day of sample collection relative to the collection date of the first sample. (C) Phylogenetic tree of the recombinant region extracted from all HSV-1 and HSV-2 sequences. The bar below the tree shows the extracted region (colored in bright blue and enlarged) relative to the rest of the genome (faded out). The branches marked with colored circles represent the position in the tree of the various samples collected from the person carrying the Seattle2 (UL47–UL50) recombinant. These colors correspond to those in B. (D) Phylogenetic tree of HSV genomes without UL47, UL48, UL49, UL49a, and UL50. The bar below the tree shows the extracted regions (colored in bright green and enlarged) relative to the rest of the genome (faded out). The branches marked with colored circles represent the position in the tree of the various samples collected from the person carrying the Seattle2 (UL47–UL50) recombinant. These colors correspond to those in B.

Recombination Analysis

Herpes simplex virus-2 genomes were individually aligned with HSV-1 KOS (JQ673480.1) and a chimpanzee herpesvirus ([ChHV] NC_023677.1) [22] sequence using MAFFT [19]. Each of these sequence trios were then run through RDP4, version Beta 4.95, using the default options (Supplementary Methods) [23]. Putative events detected by RDP were manually reviewed with apparently false-positive events (those due to sequence misalignment or in regions of poor sequence quality) excluded from further analyses. This process was then performed for all newly sequenced HSV-1 genomes with each aligned to an HSV-2 (SD90e, KF781518.1) and a ChHV reference (NC_023677.1).

We confirmed novel recombination events that were found in only 1 sample by performing Sanger sequencing across the entire event or across each of the 2 breakpoints directly from the original sample swab. Additional samples from persons with novel recombination events were sequenced when such samples were available to further confirm the recombination event and to examine the stability of the novel recombinant in vivo. For HSV-2, genotypes (nonrecombinant versus recombinant) for the UL29, UL30, and UL39 interspecies recombination events were assigned by manual review (Supplementary Methods).

RESULTS

Geographic Clustering Observed for Both Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)-1 and HSV-2 Genomes

We generated genome sequences for 59 HSV-1 clinical samples collected from 47 different individuals (Supplementary Table 1). Fifty-eight of these samples were collected in Seattle and 1 was from Uganda (Supplementary Table 3). A phylogenetic tree of these samples along with 87 publicly available sequences are shown in Figure 1A. Herpes simplex virus-1 sequences from Africa, Europe, and Asia roughly group into clades by geographic origin as previously described (clades I–VI as outlined in [24]). Sequences from North America are distributed throughout the tree, but most commonly cluster with European or Asian sequences.

For HSV-2, we generated 196 new genome sequences from 118 different individuals (Supplementary Table 2). Most (161 of 196, or 82%) of these newly sequenced samples were collected in Seattle, although samples collected in Cameroon (20), Peru (3), Senegal (10), and Uganda (2) were also sequenced (Supplementary Table 3).

For these newly sequenced genomes and for 143 previously sequenced samples, we first characterized variation at the 3 loci in HSV-2 (UL29, UL30, and UL39) where interspecies recombinant genotypes are commonly observed [12, 13]. We found that 93.4% of all available HSV-2 genomes carry recombinant HSV-1 sequence in UL29, which encodes the HSV single-stranded DNA-binding protein, ICP8 [25]. Herpes simplex virus-1 recombinant sequence in UL30, which encodes the DNA polymerase [26], is slightly less common at 90.2%. Finally, although there are numerous different recombinant genotypes within UL39, which encodes the HSV ribonucleotide reductase [13], only 34.8% of sequenced genomes carry one of these genotypes. For further examination of interspecies recombination events within UL29, UL30, and UL39, see Supplementary Note 1.

A phylogenetic tree of all available HSV-2 genomes is shown in Figure 1B. Sequences in this tree tend to cluster according to geography and genotype for the UL29, UL30, and UL39 interspecies recombination events. Clade I is composed almost entirely of African sequences and includes UL29 and UL30 nonrecombinants, whereas all currently available Asian sequences fall into Clade II. European/North American sequences are overrepresented in Clades III and IV. Clade IV is almost entirely composed of sequences with a particular UL39 recombinant genotype, whereas Clade V contains a cluster of sequences with a second UL39 recombinant genotype (Supplementary Note 1). Overall, the HSV-2 tree is dominated by 3 particularly long branches, one of which comprises Clade I sequences. The other 2 branches represent just 1 sequence each, HSV-2/Washington, USA/2015/Seattle1 (“Seattle1”, MF510363.1) and HSV-2/Washington, USA/1996/Seattle2 (“Seattle2”, MH790638.1).

Interspecies Recombination Event Spans Multiple Open Reading Frames and Is Stable Within Host

Manual review of the Seattle1 genome, which was collected from an HIV negative woman in Seattle, revealed that it contained 7 kilobases (kb) of HSV-1 sequence spanning half of UL29 and all of UL30 and UL31 (nucleotides 60 761–67 777 in SD90e reference) (Figure 2A). This event was also identified by RDP (Supplementary Figure 1). We verified the breakpoints of this event using Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Sequence 1). We next sequenced 2 additional samples from the same person (HSV-2/Washington, USA/2013/34209; HSV-2/Washington, USA/2014/13047). These 3 samples were collected over a period of 658 days (Figure 2B). The 2 additional sequences also contained the 7-kb UL29–UL31 recombination event. Across the recombinant region, the 3 sequences were identical. The 2 HSV-1 sequences with the most similarity to the recombinants within the recombinant region differed by 8 single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and were both collected in Seattle in 2009 (Figure 2C). Outside the recombinant region, there was only 1 SNV among the 3 recombinant genomes (across approximately 147 kb of sequence) (Figure 2D).

Interspecies Recombinant Generated in Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)-1/HSV-2 Genitally Coinfected Host

Manual review of the Seattle2 sequence, which was collected from a different HIV negative woman in Seattle, showed that it contained 6 kb of HSV-1 sequence, spanning half of UL47 and all of UL48, UL49, and UL49A, and most of UL50 (nucleotides 102 443 to 108 479 in the SD90e reference) (Figure 3A). The woman from whom Seattle2 was collected is notable for having HSV-1/HSV-2 genital coinfection. This event was also identified using RDP (Supplementary Figure 2). Sanger sequencing again confirmed the breakpoints of this event (Supplementary Sequence 2). Within the recombinant region, the recombinant HSV-2 sample differed from an HSV-1 sample from the same person (HSV-1/Washington, USA/1995/63175) by just 1 SNV (Figure 3B and C). We then compared the recombinant region to the rest of our HSV-1 dataset. The next most similar sequences were 2 samples collected in Seattle in 2009 that had 6 nucleotide differences. These data suggest that the HSV-1 strain collected from the person with the Seattle2 sample is most likely the HSV-1 parent of this recombinant strain (Figure 3C).

We next sequenced 3 additional HSV-2 samples (HSV-2/Washington, USA/1995/56864; HSV-2/Washington, USA/1995/57888; HSV-2/Washington, USA/1996/5934) collected before the original sample, Seattle2, from the same person. One of the 3 additional HSV-2 samples (1996/5934), collected 1 day before the original sample, Seattle2, carried the UL47–UL50 recombination event. However, 2 other samples both collected earlier than the recombinant HSV-2 samples did not contain the recombination event. There was only 1 SNV among the 4 HSV-2 samples outside the recombinant region (across approximately 148 kb of sequence) (Figure 3D), suggesting that the nonrecombinant HSV-2 strain from this person is most likely the HSV-2 parent for the Seattle2 (UL47–UL50) recombinant.

Because epitopes recognized by T-cell receptors can be exquisitely sequence-specific, we hypothesized that interspecies recombination events could modulate T-cell recognition of HSV-2. The Seattle2 (UL47–UL50) recombination event region contains an HSV-2-specific T-cell epitope within UL47 and HSV-1-specific epitopes within UL48. An HSV-2 UL47-specific CD8 T-cell clone failed to recognize the Seattle2 virus, whereas HSV-1 UL48-specific CD8 T-cell lines gained recognition of the recombinant (Supplementary Note 2), confirming that this event affects species-specific T-cell recognition. Similar effects were observed when CD4 T-cell recognition of UL30 recombinants and nonrecombinants were compared (Supplementary Note 1).

Novel Events Vary Widely in Size and Location

In addition to the large recombination events in Seattle1 and Seattle2, we observed 3 other small novel events. The first of these was a 40-bp event in UL17 (Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Sequence 3), which resulted in 9 nucleotide and 3 amino acid changes. This was observed in a single sample from a man with HIV infection from Seattle (HSV-2/Washington, USA/2005/42278). The second small event was a 52-bp event in UL28 that resulted in 4 nucleotide and no amino acid changes. It was observed in 4 samples from 4 different individuals, all of whom were from East Africa (2 from Uganda, 1 from Tanzania, and 1 from Kenya—HSV-2/Uganda/2009/3495; HSV-2/Uganda/2012/18420; HSV-2/Tanzania/2009/409; HSV-2/Kenya/2009/4463). Finally, we observed a 259-bp event in UL32 that resulted in 25 nucleotide and 4 amino acid changes (Supplementary Figure 4, Supplementary Sequence 4). This event was observed in 3 samples collected over a 12-year period from the same HIV negative man in Seattle (HSV-2/Washington, USA/2002/14972; HSV-2/Washington, USA/2014/14807; HSV-2/Washington, USA/2014/14811).

One Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)-2 Sample From Cameroon Had No Observed HSV-1 Recombination Events

One newly sequenced sample from Cameroon had the nonrecombinant genotype at the UL29, UL30, and UL39 loci and did not contain any other interspecies recombination events. This sequence (HSV-2/Cameroon/2006/16150) (Figure 1B) would be a useful alternative reference sequence for studies of HSV-2 evolution because other references all contain recombinant HSV-1 sequence. This sample has been sequenced to high quality with 50× or higher coverage for 95.8% of the full genome.

No Evidence of Interspecies Recombination Found Within Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Genomes

Finally, we examined the newly sequenced HSV-1 genomes for HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination events using both RDP and manual alignment review. In line with previous results [12, 13], we found no evidence of HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination in these genomes (Supplementary Note 3).

DISCUSSION

It has long been known that HSV-1 and HSV-2 could recombine in vitro [27–29] but only recently appreciated that interspecies recombination has also occurred in vivo [12, 13]. In this study, we conduct a comprehensive survey of all available HSV genomes, including 255 newly sequenced samples, for interspecific recombination. We performed this survey after finding 2 HSV-2 sequences in our dataset that did not phylogenetically cluster with other HSV-2 genomes and were ultimately found to contain large interspecies recombination events.

Consistent with earlier findings, we found no evidence of HSV-2 sequence in any of the HSV-1 genomes that we analyzed. Although interspecies recombination events in HSV-1 may still exist, a profound asymmetry between the receptivity of the HSV-1 and HSV-2 genomes to sequence from the other HSV species is evident. This asymmetry is particularly notable given the number of rare and likely selectively neutral recombination events we found in HSV-2. Because HSV-1 interspecies recombinants have been observed in vitro, the barrier to the presence of HSV-2 DNA in HSV-1 genomes is presumably downstream from the recombination event itself. It has been proposed that this barrier is at the level of transmission [12]. However, the failure to detect even 1 instance of recombinant HSV-1 in 135 HSV-1 genomes is suggestive that the barrier may be earlier in the HSV-1 life cycle. Overall, the one-way exchange of DNA between HSV-1 and HSV-2 in vivo is a curious feature of the evolution of these 2 viruses, which does not yet have a clear explanation.

We did identify several previously undescribed interspecies recombination events in HSV-2 genomes. These findings lead to several new insights about these events. First, the effects of interspecies recombination on HSV-2 are not restricted to the previously defined events in UL15, UL29, UL30, and UL39. Second, interspecies recombination events can be more than 10 times larger than the largest previously described event, spanning several kilobases and multiple genes. Third, we provide evidence that HSV-2 viruses with large events can be stable and persistently shed for years. Finally, our findings challenge the supposition that new interspecies recombinant genotypes are no longer being generated in modern HSV-2 populations because the Seattle2 (UL47-UL50) event seems to have arisen in the person from whom it was collected. This particular person is one of 6 genitally HSV-1/HSV-2 coinfected people from whom we have a sequenced HSV-2 sample (Supplementary Table 4). The observation of a large interspecies recombination event in 1 of only 6 samples from genitally HSV-1/HSV-2 coinfected individuals is notable considering the low incidence of such recombinants among all individuals with a sequenced HSV-2 sample (2 in 231). This raises new questions about the role of genital coinfection in the generation of interspecies recombinants. These questions are particularly important because the incidence of genital HSV-1 (and so too perhaps HSV-1/HSV-2 genital coinfection) has been shown in multiple studies to be increasing [30–32].

Our work demonstrates that there is a clear dichotomy among interspecies recombination events in HSV-2. One group comprises the previously described events in UL29, UL30, and UL39, which have reached high frequencies in the HSV-2 population. The other group consists of the 5 novel recombinants we have described here plus the previously described event in UL15, which are all present at very low frequencies. These observations coupled with direct evidence that interspecies recombination events continue to be generated in modern HSV-2 populations suggest that the evolution of HSV-2 via interspecies recombination is an active, ongoing process. Most of the recombinant genotypes generated by this process are probably selectively neutral or even deleterious, and so they exist at low frequencies or have been lost from the population. However, occasionally, as was the case of UL29, UL30, and UL39 events, these new genotypes are selectively advantageous or at least evolutionarily successful and reach high frequencies. Therefore, the possibility exists of novel viral genotypes, including those with negative implications for human health, arising through interspecies recombination. Overall, interspecies recombination represents a powerful mechanism by which HSV-2 can rapidly acquire new genomic variants.

Interspecies recombination in HSV-2 has numerous potential implications, both positive and negative, for HSV therapeutics. Although we did not observe any drug resistance mutations in our dataset, intraspecific recombination could allow HSV-2 to acquire antiviral resistance from HSV-1. Our findings also have important implications for vaccine development. In particular, our identification of clinical HSV-2 samples that have replaced large portions of their genomes with HSV-1 sequence suggests that live-attenuated HSV-2 vaccine candidates carry a significant risk of transformation to a more virulent form through either intra- or interspecific recombination. Our findings are perhaps most significant for prophylactic HSV-2 vaccine candidates because these would presumably be targeted to individuals who are HSV-2 seronegative but may be HSV-1 seropositive. The risk of interspecific recombination generating virulent virus would also extend to the use of modified HSV-2 as an oncolytic therapy. On the other hand, the disruption of latent HSV by targeted endonucleases could take advantage of the high prevalence of interspecies recombinant genotypes in UL29 and UL30 in HSV-2. These 2 essential genes have already been successfully targeted by CRISPR/Cas9 [33].

We recognize several limitations of our work. First, our identification and characterization of recombinant genotypes is limited by our sample set, which is not ideal for approximating the true prevalences of these genotypes. Our study constitutes a secondary analysis of HSV samples collected for various clinical studies and not at random from the represented populations. Second, the overrepresentation in our dataset of samples from 1 geographic location (Seattle) means that in all likelihood additional recombinant genotypes have yet to be identified, including some that may be locally common. Our results do serve to put a prior probability on interspecies recombination prevalence in HSV and suggest that more rigorous sequencing of HSV from diverse human populations is required.

We also recognize that we may have underestimated the degree of HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination, because even though the capture technique that we used for HSV sequencing greatly improved our ability to obtain high-quality, genome sequences, there remain portions of the HSV genome that are difficult to accurately sequence due to particularly high GC content and the presence of repeats. Because of these sequencing limitations, it remains challenging to confidently assess whether HSV-1 × HSV-2 recombination has an impact on these regions in either HSV genome.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our work demonstrates that the effects of interspecies recombination on the HSV-2 genome are less constrained than previously thought. We show that in addition to the 3 loci where recombinant genotypes are common (UL29, UL30, and UL39), there are several rare recombinant genotypes at other loci. These newly described events vary widely in size from approximately 50 bp to multiple kilobases in length. We also demonstrate that the generation of interspecies recombinant genotypes in circulating HSV-2 clinical strains is an ongoing process. Taken together, these new findings clarify the impact of interspecies recombination on genetic variation in HSV-2 and its potential role in HSV evolution going forward. These findings also reveal some important implications of interspecies recombination for HSV therapeutics, in particular the risk that interspecies recombination poses to the use of live-attenuated HSV-2 vaccines.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the clinical study participants from whom herpes simplex virus (HSV) samples were collected. We also thank the local study teams at the international sites in Cameroon, Peru, Senegal, and Uganda. At the Senegal site, we thank Marie-Pierre Sy for swab collection. At University of Washington, we thank Chris McClurkan and Marliis Ott for assistance with T-cell experiments.

Financial support. This work is funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant T32-AI007140; to A. M. C.).

Potential conflicts of interest. G. S. G. has received grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Alere, Gilead, and Cerus and nonfinancial support from Gilead, Merck, Janssen, Abbott, ViiV, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A. W. has received personal fees from AiCuris and Merck, grants from Genocea and Vical, and nonfinancial support from Merck. D. M. K. is a coinventor of a patent owned by the University of Washington concerning HSV vaccines and has received research funding from Sanofi Pasteur and Immune Design Corporation. C. J. has received grants from Sanofi, Genocea, and Vical and personal fees from UpToDate and Novavax. A. L. G. has previously consulted for Abbott Molecular. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: International Herpes Workshop, July 22, 2018, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

References

- 1. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, May MT, et al. Global and regional estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 1 infections in 2012. PloS One 2015; 10:e0140765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KM, Vickerman P, Gottlieb SL, Newman LM. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PloS One 2015; 10:e114989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corey L, Adams HG, Brown ZA, Holmes KK. Genital herpes simplex virus infections: clinical manifestations, course, and complications. Ann Intern Med 1983; 98:958–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1376–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson KE, Redd AD, Quinn TC, et al. Effects of HIV-1 and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection on lymphocyte and dendritic cell density in adult foreskins from Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:602–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Masese L, Baeten JM, Richardson BA, et al. Changes in the contribution of genital tract infections to HIV acquisition among Kenyan high-risk women from 1993 to 2012. AIDS Lond Engl 2015; 29:1077–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu J, Hladik F, Woodward A, et al. Persistence of HIV-1 receptor-positive cells after HSV-2 reactivation is a potential mechanism for increased HIV-1 acquisition. Nat Med 2009; 15:886–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gottlieb SL, Deal CD, Giersing B, et al. The global roadmap for advancing development of vaccines against sexually transmitted infections: Update and next steps. Vaccine 2016; 34:2939–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wertheim JO, Smith MD, Smith DM, Scheffler K, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Evolutionary origins of human herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Mol Biol Evol 2014; 31:2356–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kolb AW, Larsen IV, Cuellar JA, Brandt CR. Genomic, phylogenetic, and recombinational characterization of herpes simplex virus 2 strains. J Virol 2015; 89:6427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burrel S, Désiré N, Marlet J, et al. Genetic diversity within alphaherpesviruses: characterization of a novel variant of herpes simplex virus 2. J Virol 2015; 89:12273–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burrel S, Boutolleau D, Ryu D, et al. Ancient recombination events between human herpes simplex viruses. Mol Biol Evol 2017; 34:1713–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koelle DM, Norberg P, Fitzgibbon MP, et al. Worldwide circulation of HSV-2 × HSV-1 recombinant strains. Sci Rep 2017; 7:44084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tronstein E, Johnston C, Huang ML, et al. Genital shedding of herpes simplex virus among symptomatic and asymptomatic persons with HSV-2 infection. JAMA 2011; 305:1441–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greninger AL, Roychoudhury P, Xie H, et al. Ultrasensitive capture of human herpes simplex virus genomes directly from clinical samples reveals extraordinarily limited evolution in cell culture. mSphere 2018; 3:e00283–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davison AJ. Evolution of sexually transmitted and sexually transmissible human herpesviruses. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011; 1230:E37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colgrove R, Diaz F, Newman R, et al. Genomic sequences of a low passage herpes simplex virus 2 clinical isolate and its plaque-purified derivative strain. Virology 2014; 450-451:140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Breuer J, Grose C, Norberg P, Tipples G, Schmid DS. A proposal for a common nomenclature for viral clades that form the species varicella-zoster virus: summary of VZV Nomenclature Meeting 2008, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, 24–25 July 2008. J Gen Virol. 2010; 91(Pt 4):821–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 2013; 30:772–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2001; 17:754–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 2010; 59:307–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Severini A, Tyler SD, Peters GA, Black D, Eberle R. Genome sequence of a chimpanzee herpesvirus and its relation to other primate alphaherpesviruses. Arch Virol 2013; 158:1825–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015; 1:vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kolb AW, Ané C, Brandt CR. Using HSV-1 genome phylogenetics to track past human migrations. PLoS One 2013; 8:e76267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mapelli M, Panjikar S, Tucker PA. The crystal structure of the herpes simplex virus 1 ssDNA-binding protein suggests the structural basis for flexible, cooperative single-stranded DNA binding. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:2990–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu S, Knafels JD, Chang JS, et al. Crystal structure of the herpes simplex virus 1 DNA polymerase. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:18193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Halliburton IW. Intertypic recombinants of herpes simplex viruses. J Gen Virol 1980; 48:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morse LS, Buchman TG, Roizman B, Schaffer PA. Anatomy of herpes simplex virus DNA. IX. Apparent exclusion of some parental DNA arrangements in the generation of intertypic (HSV-1 X HSV-2) recombinants. J Virol 1977; 24:231–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davison AJ, Wilkie NM. Inversion of the two segments of the herpes simplex virus genome in intertypic recombinants. J Gen Virol 1983; 64(Pt 1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiam CW, Chan YF, Sam IC. Changing trends of genital herpes in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1982–2008. Int J STD AIDS 2010; 21:450–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gilbert M, Li X, Petric M, et al. Using centralized laboratory data to monitor trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infection in British Columbia and the changing etiology of genital herpes. Can J Public Health 2011; 102:225–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ryder N, Jin F, McNulty AM, Grulich AE, Donovan B. Increasing role of herpes simplex virus type 1 in first-episode anogenital herpes in heterosexual women and younger men who have sex with men, 1992–2006. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:416–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Diemen F R, Kruse EM, Hooykaas MJ, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of herpesviruses limits productive and latent infections. PLoS Pathog. 2016; 12:e1005701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.