Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to widespread cancelation of electively scheduled surgeries, including for colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancer. The American College of Surgeons and the Society of Surgical Oncology have released guidelines for triage of these procedures. We seek to synthesize available evidence on delayed resection and oncologic outcomes, while also providing a critical assessment of the released guidelines.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted to identify literature between 2005 and 2020 investigating the impact of time to surgery on oncologic outcomes in colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancer.

Results

For colorectal cancer, 1066 abstracts were screened and 43 papers were included. In primarily resected colon cancer, delay over 30 to 40 days is associated with lower survival. In rectal cancer, time to surgery over 7 to 8 weeks following neoadjuvant therapy is associated with decreased survival. Three hundred ninety-four abstracts were screened for pancreatic cancer and nine studies were included. Two studies demonstrate increased unexpected progression with delayed surgery over 30 days. Out of 633 abstracts screened for gastric cancer, six studies were included. No identified study demonstrated worse survival with increased time to surgery.

Conclusion

Moderate evidence suggests that delayed resection of colorectal cancer worsens survival; the impact of time to surgery on gastric and pancreatic cancer outcomes is uncertain. Early resection of gastrointestinal malignancies provides the best chance for curative therapy. During the COVID-19 pandemic, prioritization of procedures should account for available evidence on time to surgery and oncologic outcomes.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Pancreatic cancer, Gastric cancer, Time to surgery

Introduction

While the COVID-19 pandemic continues to pressure healthcare systems around the world, other chronic and acute diseases continue to affect the population. Some of these diseases, including many cancers, require timely surgical intervention. However, in order to maximize hospital capacity, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended rescheduling elective surgeries.1 Subsequently, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) published guidelines for triage of non-emergent surgical procedures.2,3

Surgery is the foundation of curative therapy for many malignancies. Delayed resection may lead to progression, resulting in clinically significant differences in complications, recurrence, and survival. Delayed treatment may also lead to the need for additional adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy, additional imaging studies for restaging, and ultimately less efficient and less effective care. Furthermore, the psychological burden of delayed surgery is likely significant.

The effects of time to surgery for many cancers have not been well characterized and the “acceptable” wait time prior to worsened outcomes is unclear. In the setting of unprecedented healthcare demands expected to continue for months to years with an accumulating backlog of delayed surgical cases, it is critical to understand which cancer surgeries should be prioritized and which can be delayed with minimal risk. We seek to synthesize the available literature on time to surgery for colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancer, providing an evidence-based approach to surgical prioritization and a critical review of the ACS and SSO guidelines.

Methods

Identification of Studies

We utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.4 In accordance with our predefined search strategy focusing on colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancers, we performed a PubMed database search for studies published between January 1, 2005, and March 23, 2020. As an example, we identified relevant abstracts for gastric cancer with “gastrectomy” or “surgery” and “gastric cancer” were searched in combination with any of the following: “delay,” “time to surgery,” “time-to-surgery,” and “timing” in order to find all studies that evaluated time to surgery with oncologic outcomes. Two authors independently screened the abstracts of all populated articles, reviewed potentially relevant complete articles, and determined which articles met inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reference lists of all included studies were reviewed to identify additional relevant studies that may have been missed with the initial search.

Study Inclusion and Data Extraction

Studies were included if the researchers evaluated the effect of time to surgery on pathologic upstaging or response, disease-free survival, or overall survival. Studies were excluded if they did not separate patients who received surgical treatment from other treatments, included patients under 18 years old, or were not written in English.

Once a paper was deemed to meet inclusion and exclusion criteria, the following data were extracted: first author, publication year, study design, number of patients, patient population, neoadjuvant therapy, age, matching/multivariate analysis, outcome measure, time to surgery groups, length of follow-up, and summary findings (with hazard ratios or odds ratios extracted when given).

Assessment of Article Quality and Bias

Two authors independently assessed included articles for level of evidence and potential bias. Levels of evidence were assigned utilizing the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines.5 We then evaluated for potential bias for observational studies and assigned a score according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.6 Ranging from zero to nine, the scale evaluates patient selection, comparability of patient populations, and outcome assessment.

Results

Colorectal Cancer

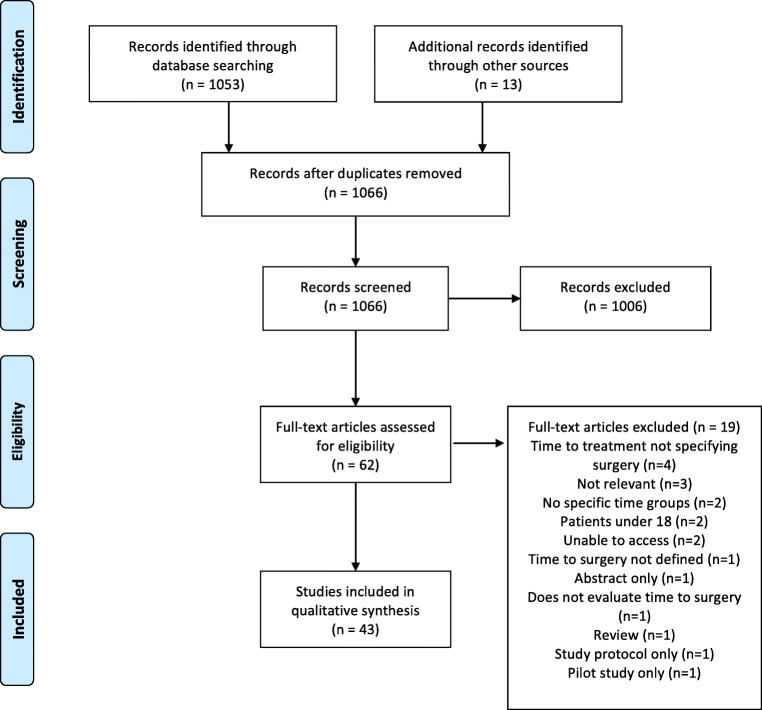

A total of 1066 abstracts were identified from the search strategy, with 1053 identified from PubMed search and an additional 13 abstracts from citation review. After screening of these abstracts, 62 full papers were reviewed and ultimately 43 studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Extracted data for included studies are shown in Table 1. Most included papers examined rectal cancer, seven studies focused solely on colon cancer, and three examined both colon and rectal cancer. As such, there is significant heterogeneity in the studies included. All studies excluded metastatic disease and emergent indication for surgery such as perforation or obstruction.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for inclusion of studies for colorectal cancer

Table 1.

Summary of included studies for colorectal cancer

| Study | Level of evidence | Quality score | n | Population | Age (years) | Outcome measure | Time to surgery/delay groups | Follow-up | Worse outcome | Summary finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akbar 20167 | 2b | 6 | 159 | Rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean not given | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 8 weeks | Median 3.6 years | No |

pCR: no difference DFS: < 8 vs ≥ 8 wk 66.7% vs 53.8% (p = 0.04) OS: < 8 vs ≥ 8 wk 68.2% vs 54.3% (p = 0.09) |

| Akgun 20188 | 1b | 327 | Rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean < 8w 60.4 ≥ 8 w 61.7 | pCR | ± 8 weeks | No | No | pCR: ≤ 8 wk vs. > 8 wk 18.6% vs. 10.0% (p = 0.027) | |

| Amri 20149 | 2b | 7 | 769 | Colon cancer with primary surgery | Mean 67 (SD 13.8) | DFS, OS | 0–13 days, 14–23, 24–37, 38–798 | Median 142 weeks | No |

DFS: per group HR 0.95 (p = 0.47) OS: per group HR 0.85 (p = 0.075) |

| Beppu 201410 | 2b | 7 | 171 | T3N0–2 Rectal Ca patients with surgery after nCRT | Median 63 (range 34–85) | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 30 days | Median 59 months | No |

pCR: ≤ 30 d vs. > 30 d 7.1% vs 1.2% (p = 0.119) DFS: ≤ 30 d vs. > 30 d 82.2% vs. 78.8% (p = 0.662) OS: ≤ 30 d vs. > 30 d 88.5% vs. 84.4% (p = 0.741) |

| Calvo 201411 | 2b | 8 | 335 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean 64.3 | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 6 weeks | Median 71 months | No |

pCR: < 6 wk vs ≥ 6 wk 8.8% vs 12.1% (p = 0.34) DFS: < 6 wk vs ≥ 6 wk 69.9% vs 74.9% (p = 0.23) OS: < 6 wk vs ≥ 6 wk 55.9% vs 70.4% (p = 0.01) |

| Curtis 201812 | 2b | 8 | 668 | Stage I-III colorectal cancer with laparoscopic surgery | Mean 71 (SD 11) | OS | ± 4 wk, ± 8 wk, ± 12 wk | 5 years | No | OS: continuous TTS HR 0.99, p = 0.52 |

| de Campos-Lobato 201113 | 2b | 7 | 177 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 57 (IQR 48–64.5) | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 8 weeks | Median 51 months | No |

pCR: < 8 vs ≥ 8 wk 16.2% vs 31.1% (p = 0.027) DFS: < 8 vs ≥ 8 wk 75.3% vs 84.7% (p = 0.26) OS: < 8 vs ≥ 8 wk 85.5% 88.2% (p = 0.74) |

| Detering 201914 | 2b | 7 | 475 | Rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean not given | DFS, OS | ± 14 weeks | NS—3-year survival | No |

DFS: < 14 vs ≥ 14 wk 74.6% vs. 70.1% (p = 0.267) OS: < 14 vs ≥ 14 wk 87.9% vs. 82.9% (p = 0.178) |

| Dolinsky 200715 | 2b | 6 | 107 | Rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 58 | Downstage, pCR, DFS | < 6 weeks, 6–8, > 8 | Median 21 months | No |

Downstaging: each week OR 1.24 (1.03–1.47) DFS: each week OR 1.05 (0.91–1.21) |

| Erlandsson 201716 | 1b | 712 | Rectal Ca with neoadjuvent radiotherapy (short) followed by surgery. | Mean 67 | DFS, OS | < 1 week vs. 4–8 weeks | Minimum follow-up of 2 years | No |

DFS: 4–8 weeks HR 0.90 (0.69–1.18) OS: 4–8 weeks HR 0.90 (0.70–1.15) |

|

| Evans 201117 | 2b | 6 | 95 | Rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 68 (range 28–88) | Downstage | < 6 weeks, 6–8, > 8 | 30 days | No |

T Downstaging: 6–8 wk: ref. < 6 wk HR 1.05 (0.30–3.70) > 8-week HR 3.79 (1.11–12.99) N Downstaging: 6–8 wk: ref. < 6 wk HR 1.18 (0.28–5.02) > 8-week HR 1.30 (0.33–5.09) |

| Flemming 201718 | 2b | 7 | 4326 | Colon cancer with primary surgery | Median 71 | DFS, OS | ± 42 days | NS | No |

DFS ≥ 42 days HR 0.88 (0.75–1.03) OS ≥ 42 days HR 1.05 (0.93–1.18) |

| Garcia-Aquilar 201119 | 2b | 7 | 144 | Stage II and III rectal Ca after nCRT with delayed surgery vs additional chemo and delayed surgery |

SG1 mean 61 (SD 12) SG2 mean 56 (SD 11) |

Downstage, pCR | SG1: surgery 6 wk post-nCRT (TTS 6 weeks) SG2: 2 cycles of FOLFOX at 4 wk, then surgery in 3–5 weeks (TTS 11 weeks) | NS | No | Pathologic response: pCR SG1 vs. SG2 18% vs. 25%, partial response: 72% vs. 75% (p = 0.0217) |

| Grass 202020 | 2b | 9 | 118,504 | Stage I-III colon Ca with primary surgery | Median 69 (IQR 59–78) | OS | < 16 days vs. ≥ 37 days | Median 5.3 years | Yes | OS: ≥ 37 d vs. < 16 d HR 1.19 (1.16–1.23) |

| Habr-Gama 200821 | 2b | 8 | 250 | Distal rectal cancer with surgery after nCRT | Mean 58.5 | Downstage, DFS, OS | ± 12 weeks | Mean 46 months | No |

Downstaging: decreased in > 12 wk (p = 0.009) Recurrence: 33% vs 30% (p = 0.45) OS: ≤ 12 wk vs > 12 wk 86.0% vs. 81.6% (p = 0.8) |

| Huntington 201622 | 2b | 9 | 6397 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 61 (range 20–90) | pCR, OS | ± 60 days | NS—108-month survival | Yes |

pCR: OR NS OS: > 60 d: HR 1.314 (1.191–1.449) |

| Jeong 201323 | 2b | 7 | 153 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean 57.8 (range 28–79) | pCR, RFS, OS | ± 8 weeks | Median 38 months | No |

pCR: < 8 wk vs. > 8 wk 16.2% vs. 18.8% (p = 0.817) DFS: < 8 wk vs. > 8 wk 64.8% vs. 66.7% (p = 0.967) OS: < 8 wk vs. > 8 wk 90.2% vs. 87.25 (p = 0.825) |

| Kaltenmeier 201924 | 2b | 9 | 514,103 | Colon cancer with primary surgery | Median 72 (IQR 61–80) | OS | < 7 days, 7–30, 31–60, 61–90, 91–120, 121–180 | No | Yes | OS: < 7 d HR 1.56 (1.45–1.68), 7–30 d ref., 31–60 d HR 1.13 (1.02–1.25), 61–90 d HR 1.49 (1.19–1.85), 91–120d HR 2.28 (1.61–3.23), 121–180 d HR 2.46 (1.48–4.09) < 8wk vs 8–12 vs > 12 wk |

| Kammar 202025 | 2b | 7 | 161 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 44 | Downstage, DFS, OS | < 8 weeks, 8–12, > 12 | Median 49.5 months | Yes |

Downstaging: not significant T or N DFS: 50.4% vs. 70.6% vs. 62% (p = 0.270) OS: 79.5% vs. 83.3% vs. 76.5% (p = 0.849) |

| Kaytan-Saglam 201726 | 2b | 7 | 136 | T3N0+ rectal cancer with neoadjuvant radiation followed by surgery |

< 4-wk group 61.2 > 4-wk group 62.8 |

DFS, OS | ± 4 weeks | Median follow-up 36 months | No |

DFS: < 4 wk vs. > 4 wk 63.1 ± 7.8 vs. 50.6 ± 2.5 (p = 0.41) OS: < 4 wk vs. > 4 wk 64.6 ± 6.9 vs 60.6 ± 1.9 (p = 0.04) |

| Kwak 201627 | 2b | 8 | 1786 | cT3–4 N0–2 M0 rectal cancer with nRCT followed by surgery | Mean not given | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 7 weeks | NS—survival curve to 6 years | No |

pCR: > 7 wk OR 1.468 (1.069–2.017). DFS ≤ 7 vs > 7 wk 71.8% vs 70.3% (p = 0.67) OS: ≤ 7 vs > 7 wk 86.5% vs 83.3% (p = 0.27) |

| Lefevre 2016 GRECCAR-628 | 1b | 265 | cT3/T4 or TxN+ rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean 63.2 (SD 10.8) | pCR |

7 weeks ± 5 days 11 weeks ± 5 days |

90 days | No | pCR: 7 wk vs 11 wk: 15.0 to 17.4% (p = 0.5983) | |

| Levick 201929 | 2b | 7 | 3469 | Rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean not given | OS | 0–7 days, 8–14, 15–27 | No | No |

OS: < 7 d ref., 8–14 d HR 1.11 (p = 0.52), 15–27 d HR 0.89 (p = 0.7) |

| Lim 200830 | 2b | 6 | 397 | Stage II-III with surgery after nCRT | Mean 56.3 | Downstage,DFS, OS | 4–6 weeks vs. ≥ 6–8 weeks | Median 31 months | No | No difference in downstaging, DFS, OS. |

| Lino-Silva 201831 | 2b | 6 | 266 | Stage I-III colon cancer with primary surgery | Median age 57 | OS | 0–24 days, 25–38, 39–60, > 60 | No | No | No significant difference in OS by stage/TTS |

| Macchia 201732 | 2b | 8 | 2094 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 65 (range 23–89) | pCR | < 6 weeks, 7–12, > 13 | No | No | pCR: RR < 6 wk ref., 7–12 wk: 1.8 ≥ 13 wk: 2.4 (p < 0.01) |

| Maliske 201933 | 2b | 6 | 87 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 55 (range 25–84) | pCR, OS | ± 8 weeks | No | No |

pCR: < 8 vs ≥ 8 wk 27.5% vs. 27.7% (p = 0.99) OS: ≥ 8 wk HR 1.61 (0.74–3.50) |

| Mihmanli 201634 | 4 | 5 | 87 | Rectal cancer with nRCT followed by surgery | < 8 weeks mean 53.7, > 8 weeks mean 58 | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 8 weeks | 34.5 months | No |

pCR: no effect. DFS < 8 vs ≥ 8 wk 50.8 vs. 71.2 months (p = 0.01) OS < 8 vs. ≥ 8 wk 62.8 vs 77.9 (p = 0.02) |

| Plastiras 201735 | 4 | 5 | 65 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean age 70.9 | Downstage, DFS | ± 6 weeks | NS—up to 100 months | No | No significant difference in downstaging or DFS |

| Probst 201536 | 2b | 9 | 17,255 | Stage II and III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean 58.5 | Downstage, pCR | < 6 weeks, 6–8, > 8 | 30 days | No |

Downstaging: 6–8 weeks ref., > 8 wk: OR 1.11 (1.02–1.25) pCR: 6–8 wk ref., < 6 wk: HR 0.79 (0.68–0.91) > 8 wk: 1.12 (1.02–1.28) |

| Rombouts 201637 | 2b | 9 | 1290 | Rectal cancer with nRCT followed by surgery, early (ET) and locally advanced (LARC) | Mean 63 to 68 by group | pCR, OS | 5–6 weeks, 7–8, 9–10, 10–11, 11–12, 13–14 | NS—survival to 5 years | Yes | ET—no effect on pCR, OS. LARC-pCR 5–6 wk (OR 0.57, 0.25–1.28) 7–8 wk ref., 9–10 wk (OR 1.56, 1.03–2.37), 11–12 wk (OR 1.94, 1.15–3.26), 13–14 wk (OR 1.44, 0.68–3.04). No effect on OS |

| Roxburgh 201938 | 2b | 7 | 607 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | < 55 years, 55–75, > 75 | pCR | <8 weeks, 8–12, 12–16 | No | No | pCR: < 8 wk vs 8–12 vs 12–16: 18% vs 18% vs 9% (p = 0.165) |

| Saglam 201439 | 1b | 153 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Mean 53.1 | Downstage, DFS, OS | 4 weeks vs 8 weeks | Median 4 wk—56.8; 8 wk—59.3 months | No |

Pathologic response: not significant DFS: 4 wk vs 8 wk 73.2% vs. 70.5% (p = 0.80) OS: 4 wk vs 8 wk 76.5% vs. 74.2% (p = 0.60) |

|

| Shin 201340 | 2b | 9 | 1946 | Primary surgery within 1 year of diagnosis (colorectal subgroup) | Mean 61.8 | OS | ≤ 1 week, > 1–4, > 4–12, > 12 | Median 4.7 years | Yes | OS: ≤ 1 wk HR 1.68 (1.31–2.16), 1–4 wk ref., 4–8 wk HR 1.07 (0.73–1.57), 8–12 wk HR 0.84 (0.39–1.82), > 12 wk HR 2.65 (1.50–4.70) |

| Simunovic 200941 | 2b | 7 | 7989 | Colon cancer with primary surgery | Mean not given | DFS, OS |

Consult to surg: 1–7 days, 8–14, 15–21, ≥ 22 d Diagnosis to surg: 1–14 days, 15–28, 29–42, ≥ 43 |

NS | No |

DFS: TTS not significant OS: ≥ 22 days consult—1.1 (1.0–1.2), ≥ 43 d diagnosis 1.2 (1.1–1.3) |

| Sloothaak 201342 | 2b | 8 | 1593 | Rectal Ca with total mesorectal excision after nCRT | Mean 63–64 by group | pCR | < 13 weeks, 13–14, 15–16, > 16 | 30 days | No | pCR: < 15 or > 16 wk: ref. 15–16 wk: HR 1.63 (1.20–2.23) |

| Sun 201643 | 2b | 9 | 11,760 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 58 (IQR 50–67) | Downstage, OS | ± 56 days | NS—5-year survival | Yes | Downstaging: ≥ 56 d: OR 1.12 (1.02–1.23) OS: ≥ 56 d: HR 1.20 (1.10–1.32) |

| Tran 200644 | 2b | 5 | 48 | Stage II-III mid-distal rectal cancer with surgery after nCRT | Mean ≤ 8wk: 62.3 > 8wk: 58.1 | Downstage | ± 8 weeks | Mean 27.7 months | No | Downstaging≤ 8 vs > 8 wk 44% vs 41% (p = 0.92) |

| Trepanier 202045 | 2b | 8 | 408 | Stage I-III colorectal cancer with primary surgery | Mean 69.8 (SD 11.2) | DFS, OS | < 4 weeks, 4–8, ≥ 8 | Mean 58.4 months | No |

DFS: < 4 wk ref. 4–8 wk HR: 0.96 (0.47–1.95) ≥ 8 wk 0.86 (0.42–1.78) OS: < 4 wk ref. 4–8 wk HR 2.51 (0.70–9.03) ≥ 8 wk 2.15 (0.59–7.81) |

| Tulchinsky 200846 | 2b | 7 | 132 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median 64 (range 23–87) | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 7 weeks | Median 33 months | No |

pCR: ≤ 7 wk vs > 7 wk 17% vs 35% (p = 0.03) DFS: greater in > 7 wk (p = 0.05) OS: not significant (p = 0.07) |

| Veenhof 200647 | 2b | 5 | 108 | Stage II-III mid-distal rectal cancer with surgery after neoadjuvant radiation |

Median ≤ 2 weeks: 67 > 6–8 weeks: 63 |

Downstage, pCR, OS | < 2 weeks vs 6–8 weeks | Median 34 months | No |

Downstaging: < 2 vs 6–8 wk 26% vs. 55% (p < 0.01) DFS: < 2 vs 6–8 wk 74.6% vs. 69.4% (p = 0.76) OS: < 2 vs 6–8 wk 66.4% vs. 73.3% (p = 0.12) |

| Wanis 201748 | 2b | 7 | 908 | Colon cancer with primary surgery | Mean not given | DFS, OS | ± 30 days | Median 2.7 years | No |

DFS: > 30 d HR 0.81 (0.57–1.21) OS: > 30 d HR 0.87 (0.66–1.10) |

| Wolthuis 201249 | 2b | 8 | 356 | Stage II-III rectal Ca with surgery after nCRT | Median ≤ 7 weeks: 64 > 7 weeks: 62 | pCR, DFS, OS | ± 7 weeks | Median 4.9 years | No |

pCR: ≤ 7 vs > 7 wk 15.9% vs 28.4% (p = 0.006) DFS: ≤ 7 vs > 7 wk 73% vs 83% (p = 0.026) OS: ≤ 7 vs > 7 wk 83% vs 91% (p = 0.046) |

NS, not stated; OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; TTS, time to surgery; pCR, pathologic complete response; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; ref., reference group; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; d, days; wk, weeks

All five of the randomized controlled trials included in this analysis evaluated time to surgery in rectal cancer following neoadjuvant therapy. The Stockholm III trial is a Swedish multicenter, randomized, non-inferiority trial evaluating neoadjuvant radiation therapy regimens and timing to surgery. This study randomized patients to three arms: (1) short course radiotherapy followed by surgery within 1 week, (2) short course radiotherapy followed by surgery after 4 to 8 weeks, and (3) long course radiotherapy with surgery after 4 to 8 weeks. Pettersson et al.’s interim analysis showed better tumor downstaging in the delay group, consistent with the Lyon study.50 Midterm results of the Stockholm III trial demonstrated non-inferior oncologic outcomes with surgical delay after short course radiation, with a minimum follow-up of 2 years.16 Perioperative morbidity was significantly higher with immediate surgery following radiation therapy. These results suggest that delay to surgery of 4 to 8 weeks following neoadjuvant therapy is safe from an oncologic standpoint. This is supported by large retrospective cohort studies, such as Probst et al., which demonstrated higher odds of pathologic complete response and downstaging in stage II and III rectal cancer patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgical resection in the National Cancer Database (NCDB).36

Two other randomized controlled trials evaluated longer delays to surgery. Akgun et al. enrolled 327 patients and demonstrated better disease regression and pathologic complete response with a greater than 8-week interval to surgery, but lacked long-term follow-up.8 The GRECCAR-6 study randomized cT3/T4 or TxN+ patients to an even longer delay of 7 weeks vs. 11 weeks. There was no increased rate of pathologic complete response in the 11-week delay group, and in fact, there were more perioperative complications for patients who had the longer delay.28 This argues that the benefit of delaying surgery after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy does not extend beyond a period of 11 weeks.

One drawback to the contemporary randomized control trials included in this review is that they all lack long-term follow-up. However, there are several high-quality retrospective cohort studies that evaluate survival. Sun et al. examined stage II and III rectal cancer patients in the NCDB who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgical resection at a short interval (< 56 days) or long interval (≥ 56 days). Notably, the 7-week cutoff defined in this study was objectively determined with modeling an inflection point. Patients in the longer delay group had higher likelihood of pathologic downstaging but worse long-term survival (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.10–1.32).43 This was corroborated by Huntington et al. who looked at a similar population with a cutoff of 60 days and also demonstrated reduced long-term survival (HR 1.31, 95% CI 1.19–1.45).22

Ten studies included in this analysis evaluated colon cancer outcomes—all of these studies were retrospective cohort studies and none involved neoadjuvant therapy. Several large retrospective cohort studies did demonstrate worse outcomes with surgical delay. Kaltenmeier et al. evaluated more than 500,000 colon cancer patients in the NCDB. Time to surgery was divided into under 7, 7–30, 31–60, 61–90, 91–120, and 121–180 days from diagnosis to surgery. There was a marked increase in mortality risk with surgery done under 7 days vs. over 30 days from diagnosis. Waiting 4 to 6 months carried with it a 2.46-fold risk of mortality.24 Grass et al. included 118,504 stage I-III colon cancer patients in the NCDB and evaluated outcomes in patients who underwent surgery under 16 days from diagnosis vs. over 37 days from diagnosis with median follow-up of 5.3 years. There was significantly worse 5- and 10-year survival in the long delay group. When evaluating timing as a continuous variable, the authors noted a significant decrease in survival at a delay of 40 days.20 In a study examining surgical delay and outcomes across multiple cancer types, Shin et al. found that delays greater than 12 weeks in colorectal cancers were associated with a 2–3-fold mortality over a median follow-up of 4.7 years.40 Finally, Simunovic et al. used a linked SEER-Medicare database and found that a delay of 43 days from diagnosis or 22 days from surgical consultation was associated with worse overall survival (HR 1.1, 95% CI 1.0–1.2 and HR 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3 respectively).41

However, some studies of colon cancer did not find an impact of delay on survival. Flemming et al. followed patients undergoing elective colon resection in Canada for 4–10 years, finding that longer time to surgery was not associated with worse cancer specific survival or overall survival at a cutoff of 42 days or when time to surgery was considered a continuous variable.18 Similarly, Wanis et al. evaluated stage I to III cancer who were stratified by wait time of 30 days. There was no difference in disease-free survival or overall survival over a median follow-up of 2.7 years. Subgroup analysis of the group who waited 60–90 days also did not demonstrate any significant impact on survival.48

Pancreatic Cancer

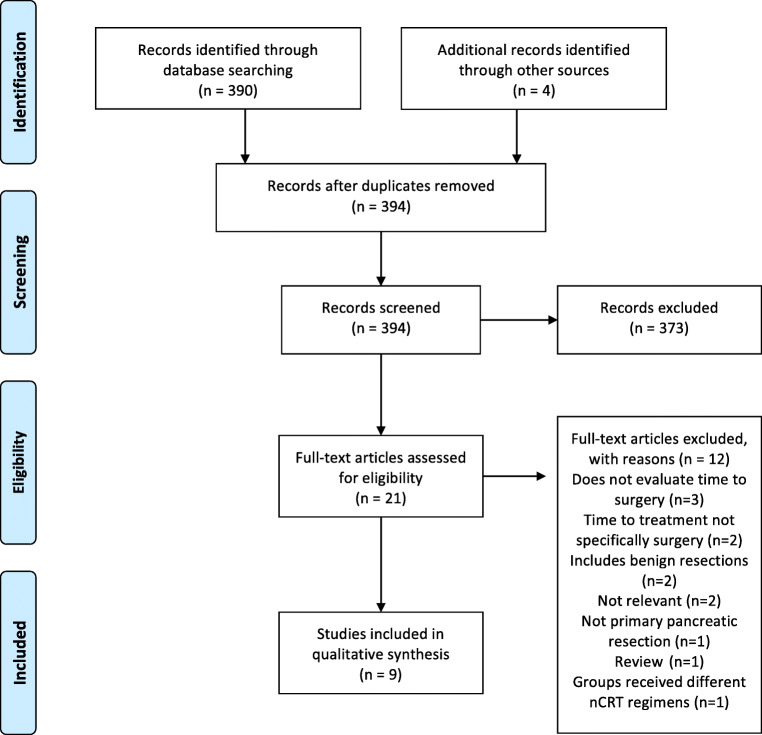

The search strategy identified 394 abstracts: 390 from PubMed and an additional four abstracts through reference list review. Twenty-one full papers were reviewed and ultimately nine papers met the criteria to evaluate whether surgical delay affects outcomes in pancreatic cancer (Fig. 2). Extracted data for included studies are shown in Table 2. While outcomes and primary endpoints varied, most focused on overall survival, resectability, or progression of disease. Overall, the quality of the studies was high with low risk of bias. Most studies specifically excluded patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, while one included them and one specifically studied only that patient group.56–59 There was a trend to recent publication with seven studies published after 2017.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram for inclusion of studies for pancreatic cancer

Table 2.

Summary of included studies for pancreatic cancer

| Study | Level of evidence | Quality score | n | Population | Age (years) | Outcome measure | Time to surgery/delay groups | Follow-up | Worse outcome | Summary finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eshuis 201051 | 1b | NA | 185 | Obstructive Jaundice with pancreatic cancer | ES: 64.6 ± 9.5 PBD: 64.7 ± 10.3 | OS | PBD with 4-week delay or immediate surgery | 2 years | No |

OS: resection TTS every 1 wk: HR 0.85 (0.75–0.96) Any surgery (palliative or resection) TTS every 1 wk: HR 0.91 (0.84–0.91) |

| Healy 201852 | 2b | 9 | 239 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or ampullary cancer | < 25 d: 63.6 ± 9.8; > 25 d: 66 ± 9.4 | Upstaging, DFS, OS | ± 25 days | Mean 23 ± 19 months | No |

Upstaging: < 25 d = 6%; > 25 d = 17% (p < 0.05) DFS: ≥ 25 d HR: 0.998 (0.988–1.007) OS: ≥ 25 d HR: 1.004 (0.996–1.013) |

| Kirkegard 201953 | 2b | 7 | 873 | Pancreatic cancer—resection or palliative surgery | Mean 67 (35–86) | OS | < 28 days, 28–55 days, > 55 days | NS | No | OS (months): < 28 d: 22.1 (19.3–25.9), 28–55 d: 22.0 (17.4–26.2), ≥ 56 days: 21.8 (16.3–26.1) |

| Marchegiani 201854 | 2b | 9 | 217 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Median 66 (37–85) | OS | ± 30 days, ± 45 days, ± 60 days | Median 15 m | No | OS: > 30 d: HR 1.44 (0.57–3.63), > 45 d: HR 1.50 (0.56–4.04), > 60 d: HR 1.27 (0.32–4.96) |

| Mirkin 201855 | 2b | 9 | 14,807 | Stage I or II pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Depending on group mean 65.6–68.9 | OS | < 1 week. > 1–2 weeks. > 2–4 weeks, > 4–8 weeks. > 8–12 weeks | NR | No | OS: < 1 wk ref., 1–2 wk = HR: 1.12 (1.10–1.19), 2–4 wk HR 1.03 (0.97–1.08), 4–8 wk HR 0.98 (0.93–1.04), 8–12 wk HR 0.92 (0.82–1.02) |

| Sanjeevi 201656 | 2b | 9 | 349 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Median 68 (42–86) | Upstaging, OS | ± 32 days | NR | No |

Upstaging: ≤ 32 d: HR 0.42 (0.21–0.89) OS: ≤ 32 d: HR 0.88 (0.61–1.26) |

| Shin 201957 | 2b | 9 | 831 | PBD followed by surgery | Mean 63.62 ± 9.8 | OS | < 2 weeks vs > 3 weeks | At least 3 years | No | OS: < 2 wk vs > 3 wk: 19.2 vs 21.4 months (p = 0.960) |

| Swords 201858 | 2b | 9 | 16,763 | Stage I or II pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Depending on group mean 65.8–68.7 | OS | < 15 d days, 15–42 days, 43–100 days | NR | No | OS: 1–14 d: ref., 15–42 d: HR 0.94 (0.90–0.97), 43–100 d: HR 0.91 (0.86–0.96) |

| Teng 202059 | 2b | 9 | 1610 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with neoadjuvant therapy | Mean 63.1 ± 9.7 | OS | ± 12 weeks | Not stated | No | OS: ≥ 12 wk: HR 0.80 (0.65–0.99) |

NS, not stated; OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; TTS, time to surgery; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; ref., reference group; ES, early surgery; PBD, preoperative biliary drainage; d, days; wk, weeks

Only one study demonstrated an improvement in overall survival with early resection. Marchegiani et al. retrospectively evaluated 217 patients who underwent surgery for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, stratifying patients by time to surgery of less than or greater than 30 days. There was no difference in overall survival between the groups (31 months vs. 29 months, p = 0.2). However, in a subgroup analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas under 20 mm at diagnosis (n = 84), improved overall survival was noted with early resection within 30 days (at least 32 vs. 28 months, p = 0.02).54

Eshuis et al.’s study was the only randomized controlled trial, randomizing patients with obstructive jaundice into early surgery vs. biliary drainage followed by surgery. With a time to surgery difference of 4 weeks (1.2 weeks vs. 5.2 weeks), there was no difference in unadjusted survival (p = 0.91) but early surgery was associated with fewer complications related to either biliary drainage or surgery (29% vs 76%, p < 0.01). Following multivariable analysis, a longer time to surgery was associated with improved overall survival after surgery (per week HR: 0.90, 0.83–0.97).51 Two large studies analyzed data from the NCDB in patients with stage I or II pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mirkin et al. found that greater time to surgery was associated with improved overall survival with the lowest mortality in the 8–12-week group (HR 0.82, p = 0.001).55 Similarly, Swords et al. also showed the best overall survival was in the longest delay group of 43–120 days (HR 0.91, 0.86–0.96) also finding decreased perioperative mortality.58

Two studies analyzed tumor progression at time of surgery. In 349 patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Sanjeevi et al. demonstrated that operating within 32 days from imaging reduced the risk of tumor progression to unresectable disease by half. However, in those with tumor resection, time interval did not have a significant impact on overall survival.56 Healy et al. also found that in patients with resectable pancreatic or periampullary adenocarcinoma, surgery within 25 days reduced unexpected progression (6% vs 17%, p < 0.05), but did not change overall survival in the cohort. In fact, in periampullary carcinoma, waiting was associated with improved overall survival (median OS 74.3 vs. 29.6 months, p < 0.05).52

Teng et al.’s study was the only study to focus on patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy and found that a time to surgery of more than 12 weeks following conclusion of neoadjuvant therapy was associated with more patients with clinical stage III cancer (33.5% vs 14%, p < 0.001). However, these patients had significantly prolonged survival on multivariate analysis (HR 0.80, 0.65–0.99).59

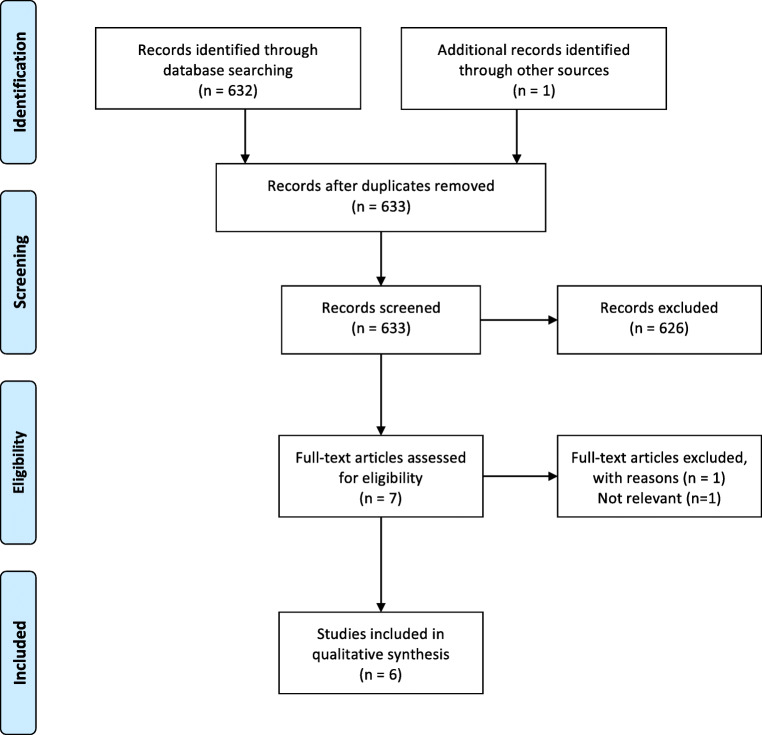

Gastric Cancer

In total, 633 abstracts were identified from the search strategy, with 632 from PubMed and one abstract identified through reference list review. Seven full papers were reviewed and ultimately six papers met the criteria to evaluate whether surgical delay affects outcomes in gastric cancer (Fig. 3). Extracted data for included studies are shown in Table 3. Four studies evaluated the timing to surgery in patients with gastric cancer who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy, one study evaluated gastrectomy both with and without neoadjuvant therapy (although only specifically evaluated time to surgery in the primary gastrectomy group), and one study evaluated the timing to surgery after neoadjuvant therapy. All six studies were well-designed retrospective cohorts and categorized as level 2b evidence.

Fig. 3.

Flow diagram for inclusion of studies for gastric cancer

Table 3.

Summary of included studies for gastric cancer

| Study | Level of evidence | Quality score | n | Population | Age (years) | Outcome measure | Time to surgery/delay groups | Follow-up | Worse outcome | Summary finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brenkman 201760 | 2b | 8 | 2077 | Stage cT1-4a, N0–3, M0. Subgroup with primary surgery. | Mean 73.5 (SD 10.1) | OS | ≤ 5 weeks, 5–8, > 8 | NS—5-year survival | No |

OS: ≤ 5 wk ref. 5–8 wk 0.92 (0.81–1.05) ≥ 8 wk 0.95 (0.79–1.08) Additional wk HR 0.99 (0.98–1.01) |

| Cha 201961 | 2b | 7 | 302 | Primary surgery following incomplete endoscopic resection | Mean 60.53 (SD 12.23) | DFS, OS | ± 29 days | Median 42 months ± 21.2 | No |

DFS: > 29 days: HR: 0.367 (0.103–1.302) OS: > 29 days HR 0.193 (0.027–1.394) |

| Fujiya 201962 | 2b | 9 | 556 | Stage IA or IB with primary surgery | Median 64 IQR 53–75 | OS | < 61 days vs. 61–90 vs. 91–180 | Median follow-up 60.9 months | No | OS: < 61 days ref., 61–90 days HR: 0.69 (0.37–1.31), 91–180 days HR: 1.03 (0.56–1.88) |

| Furukawa 201963 | 2b | 8 | 696 | Stage II and III patients with primary surgery | Median 67 (IQR 59–74) | OS | ≤ 30 days, 30–60, > 60–90 | NS—5-year survival | No | OS: ≤ 30 d: ref., 30–60 d: HR 0.894 (0.659–1.212); > 60–90 d: HR 0.801 (0.541–1.188) |

| Kim 201464 | 2b | 6 | 154 | Primary surgery following incomplete endoscopic resection | Mean 60.7 (SD 9.8) | DFS, OS | ± 29 days | ≤ 29 days: Median 19 months > 29 days median 31.5 | No | No difference in recurrence or mortality |

| Liu 201865 | 2b | 8 | 176 | Surgery following nCRT | Median 57 (Range 21–75) | pCR, DFS, OS | < 4 weeks, 4–6 weeks, > 6 weeks | NS—3-year survival | No | PCR: < 4 wk OR 0.69 (0.22–2.13), 4–6 wk OR 0.26 (0.07–0.096), 6 wk ref.; DFS: < 4 wk HR 0.43 (0.10–1.85), 4–6 wk HR 0.93 (0.23–3.80), > 6 wk ref. OS: < 4 wk HR 0.49 (0.11–2.129), 4–6 wk HR 0.99 (0.24–4.06), > 6 wk ref |

NS, not stated; OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; TTS, time to surgery; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; ref., reference group; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; d, days; wk, weeks

Three studies investigated patients with early stage gastric cancer (stage IA, IB, or II). Kim et al. divided patients in two groups (≤ 29 vs > 29 days) and surgery followed non-curative endoscopic resection. There was no difference in disease-free survival with a mean follow-up of 26.7 months.64 A follow-up report evaluating longer-term outcomes by Cha et al. (mean follow-up 42 months) found no difference in disease-free survival or overall survival after multivariate analysis.61 Fujiya et al. looked at stage Ia/Ib gastric cancer with a time to surgery up to 180 days (median wait time 72 days). On a multivariate analysis, time to surgery did not impact survival.62

The remaining studies involved more advanced gastric cancer (stage II, III). The largest study was by Brenkman et al. with 2077 patients undergoing resection with or without neoadjuvant treatment. Increasing time to surgery up to greater than 8 weeks in the primary gastrectomy group did not impact overall survival.60 Furukawa et al. divided the time to surgery into three groups (30–60 days, 60–90, > 90). On initial univariate analysis, early surgery was associated with worse survival; however, after multivariate adjustment, time to surgery was not an independent prognostic factor for survival.63 One study included patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Liu et al. divided the time to surgery from completion of chemotherapy into three groups (< 4 weeks, 4–6, > 6). Consistent with the prior studies, the interval to surgery did not impact overall survival or disease-free survival, but a time to surgery over 6 weeks improved pathologic complete response.65

Discussion

Colorectal Cancer

In both colon and rectal cancer, there is moderate evidence of worse outcomes with delaying surgical resection. To our knowledge, there have been no consensus guidelines published on the timing of surgical resection in colorectal cancer. The ACS triage guidelines for colorectal cancer recommend resection as soon as feasible, including for primary resection of colon cancer.2 The guidelines also recommend considering delayed resection of locally advanced resectable colon cancer with administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for 2 to 3 months followed by surgery.

Although not seen in smaller cohort studies, multiple large high-quality studies of the NCDB and SEER-Medicare databases demonstrate increasing time to surgery in colon cancer is associated with lower survival, with worse outcomes seen at as little as 30 to 40 days.20, 24, 41 These data support the expeditious resection of colon cancer whenever possible based upon available resources.

Delayed resection of colon cancer leads to delayed staging, which in the setting of positive nodes would delay administration of chemotherapy. If resection must be delayed, strong consideration should be given to administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to all colon cancers. Pilot study results from the FOxTROT Collaborative Group demonstrated that in high risk stage II and III colon cancer, 6 weeks of neoadjuvant oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil therapy versus primary resection resulted in increased downstaging (p = 0.04), decreased apical node involvement (1% vs. 20%, p < 0.0001), and decreased positive margins (4% vs. 20%, p = 0.002).66 Recently presented interim results demonstrate similar rates of 2-year relapse or persistent disease between the neoadjuvant and control groups (14% vs. 18%, p = 0.11).67 Given the current paucity of data for colon cancer, if neoadjuvant chemotherapy is administered to delay resection in this setting, surgeons should obtain frequent interval imaging to ensure appropriate response followed by timely resection.

The ACS guidelines recommend resection as soon as feasible for rectal cancer following neoadjuvant therapy and consideration of delay for rectal cancer cases with “clear and early evidence of downstaging from neoadjuvant chemoradiation,” either with additional wait time or additional rounds of chemotherapy.2

The question of optimal time to surgery after neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer has been under intense investigation since the Lyon R90-01 randomized trial demonstrated improved tumor downstaging and no difference in survival with a longer wait time to surgery (6 to 8 weeks) after radiation in 1999.68 Following neoadjuvant therapy, longer delay is associated with improved pathologic downstaging at a variety of time points. The impact of surgical delay on survival is less clear. Two large NCDB studies demonstrate worse survival with time to surgery greater than 7 to 8 weeks.22, 43 However, most studies—with much smaller cohorts and largely at single institutions—did not show a survival difference with surgical delay. Most of the time points investigated were at shorter intervals with few beyond 8 weeks. Given the accumulated evidence, delayed surgery up to 8 weeks following the completion of neoadjuvant therapy appears safe and allows increased pathologic response. Given the progressive nature of rectal cancer and several large studies demonstrating worse survival after 8 weeks, surgery should not be delayed beyond this point when possible.

Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is an aggressive malignancy, with a reported tumor doubling time of 159 days and very poor overall survival, even in the setting of resected early stage disease.69 The data on time to surgery and pancreatic cancer survival are equivocal. Some evidence suggests that resection within 30 days decreases unexpected progression and potentially improves survival for pancreatic adenocarcinomas under 2 cm.52,54,56 However, the remainder of the included studies did not find an association between longer time to surgery and worse survival. Several large high-quality retrospective cohort studies actually demonstrated improved outcomes with surgical delay of at least 6 weeks, with clear concern for selection bias in the population. Importantly, increased time to surgery may result in progression to unresectable disease, selecting for less aggressive malignancies in the delayed surgery groups. Additional selection bias may also occur in the early groups with surgeons operating more quickly on aggressive appearing or borderline resectable cancers. For surgery after neoadjuvant therapy, the one study that evaluated time to surgery following neoadjuvant therapy also found improved outcomes with increasing time to surgery up to over 12 weeks, but this suffers from the same potential bias noted above.59

While NCCN guidelines for pancreatic adenocarcinoma recommend surgery should occur 4 to 8 weeks after completion of neoadjuvant therapy, there are no guidelines on timing for patients undergoing primary surgery to our knowledge.70 Minimal evidence exists to provide a recommendation for acceptable delay in time to surgery in pancreatic cancer. The Society for Surgical Oncology (SSO) COVID-19 guidelines recommend administration of neoadjuvant therapy in all resectable pancreatic cancers as a means to delay surgery in this group.3 This is supported by recent literature demonstrating no difference in mortality between patients with resected stage I pancreatic adenocarcinoma who received neoadjuvant therapy versus adjuvant therapy, suggesting that this is an acceptable strategy to delay surgery.71 Other recommendations from the SSO include extending neoadjuvant chemotherapy duration or addition of radiotherapy. It is reasonable to either administer neoadjuvant therapy to all resectable pancreatic cancers or perform expeditious upfront resection based upon patient and hospital factors, including bed availability, local disease burden, and local incidence trajectory.

Gastric Cancer

We did not find any studies that demonstrated an association between delayed surgery and worsening survival in gastric cancer. To our knowledge, no specific guidelines exist for an appropriate time interval for surgery in patients with gastric cancer. The SSO COVID-19 guidelines recommend endoscopic resection of amenable cT1a lesions, primary resection of cT1b lesions, and neoadjuvant therapy for cT2 or higher lesions.3 For patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy, extending therapy should be considered if patients are responding to and tolerating treatment.

For stage I gastric cancer, no evidence of worsened survival was noted even with a time to surgery over 90 days. Early gastric cancers that are amenable should be endoscopically resected if possible; however, some evidence suggests surgical resection may be delayed 3 months without worse oncologic outcomes. The natural history of early gastric cancer was reported by Tsukuma et al., who followed 71 patients with biopsy-proven early gastric cancer who did not undergo initial resection. Only 63% of early gastric cancer progressed to an advanced stage in 5 years, suggesting a significant portion of early gastric cancers do not progress and may have a more indolent course.72 Given this, in the setting of severe resource constraints, deferring surgery for up to 3 months versus potential neoadjuvant therapy should be considered.

For more advanced gastric cancers, insufficient evidence exists to provide recommendations on time to surgery following neoadjuvant therapy (as recommended by the SSO). A single paper investigated time to surgery following neoadjuvant therapy, with no impact on survival with time to surgery greater than 6 weeks. In fact, this group had increased pathologic complete response.65 Therefore, it may be reasonable to delay up to 6 weeks in the neoadjuvant setting even if additional therapy cannot be given due to patient tolerance.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. Due to the nature of cancer as a progressive disease, increasing time to surgery should result in worse outcomes in the absence of other therapy. Therefore, the questions we try to answer in this study is at what delay is there clear evidence of worsened outcomes and how can this evidence can be used to inform triage decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. All of the included literature for primary resection was retrospective, and although matching was utilized, there is clear selection bias in the studied populations. Surgeons tend to operate sooner on more aggressive cancers or when patients are at risk for immediate complications of their malignancy. Cancer that progressed to unresectable disease due to surgical delay similarly is not included in outcomes. Despite careful matching, numerous studies actually show improved survival with delay due to these reasons. In the studies included involving neoadjuvant therapy, there were a handful of prospective randomized studies; however, these failed to capture long-term outcomes. Nearly all of the time points evaluated were chosen arbitrarily and were highly variable between studies. Our review is descriptive—given the heterogeneity in patient populations, study designs, and outcomes evaluated, we did not pool data. Finally, this review only encompassed a search of a single database, although additional relevant literature was identified through a thorough review of references.

Conclusions

Moderate evidence suggests that delayed resection of colorectal cancer worsens survival, although the evidence for worsened outcomes in pancreatic and gastric cancers is equivocal. Early surgical management of cancer often provides the best chance at curative treatment, as delay invites further invasion, progression to unresectable disease, or metastasis. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a serious challenge to timely surgical management, necessitating the evidence-based prioritization of certain cancer operations. Resection should occur expeditiously depending upon the availability of hospital resources and local disease burden. When timely resection cannot occur, alternative therapies including neoadjuvant treatment should be considered.

Contributions

All authors meet the stated criteria under “Definition of Authorship” listed in the Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery instructions for authors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Facilities: Preparing for Community Transmission of COVID-19 in the United States. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/healthcare-facilities/guidance-hcf.html. Accessed 03/09/2020.

- 2.American College of Surgeons. COVID-19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care. 2020. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case.

- 3.Society of Surgical Oncology. COVID-19 Resources. 2020. https://www.surgonc.org/resources/covid-19-resources/. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 4.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips B, Ball, B, Sackett, D, Badenoch, D, Straus, S, Haynes B, Dawes, M. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence 2009. https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/.

- 6.Wells G SB, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2003. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 7.Akbar A, Bhatti AB, Niazi SK, Syed AA, Khattak S, Raza SH, et al. Impact of Time Interval Between Chemoradiation and Surgery on Pathological Complete Response and Survival in Rectal Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(1):89–93. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akgun E, Caliskan C, Bozbiyik O, Yoldas T, Sezak M, Ozkok S, et al. Randomized clinical trial of short or long interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105(11):1417–25. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amri R, Bordeianou LG, Sylla P, Berger DL. Treatment delay in surgically-treated colon cancer: does it affect outcomes? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(12):3909–16. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3800-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beppu N, Matsubara N, Noda M, Yamano T, Doi H, Kamikonya N, et al. The timing of surgery after preoperative short-course S-1 chemoradiotherapy with delayed surgery for T3 lower rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(12):1459–66. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1997-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvo FA, Morillo V, Santos M, Serrano J, Gomez-Espi M, Rodriguez M, et al. Interval between neoadjuvant treatment and definitive surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer: impact on response and oncologic outcomes. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(10):1651–60. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1718-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis NJ, West MA, Salib E, Ockrim J, Allison AS, Dalton R, et al. Time from colorectal cancer diagnosis to laparoscopic curative surgery-is there a safe window for prehabilitation? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(7):979–83. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Campos-Lobato LF, Geisler DP, da Luz MA, Stocchi L, Dietz D, Kalady MF. Neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: the impact of longer interval between chemoradiation and surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(3):444–50. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Detering R, Borstlap WAA, Broeders L, Hermus L, Marijnen CAM, Beets-Tan RGH, et al. Cross-Sectional Study on MRI Restaging After Chemoradiotherapy and Interval to Surgery in Rectal Cancer: Influence on Short- and Long-Term Outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(2):437–48. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-07097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolinsky CM, Mahmoud NN, Mick R, Sun W, Whittington RW, Solin LJ, et al. Effect of time interval between surgery and preoperative chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin on outcomes in rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96(3):207–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.20815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erlandsson J, Holm T, Pettersson D, Berglund A, Cedermark B, Radu C, et al. Optimal fractionation of preoperative radiotherapy and timing to surgery for rectal cancer (Stockholm III): a multicentre, randomised, non-blinded, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):336–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans J, Tait D, Swift I, Pennert K, Tekkis P, Wotherspoon A, et al. Timing of surgery following preoperative therapy in rectal cancer: the need for a prospective randomized trial? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(10):1251–9. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182281f4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flemming JA, Nanji S, Wei X, Webber C, Groome P, Booth CM. Association between the time to surgery and survival among patients with colon cancer: A population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(8):1447–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Aguilar J, Smith DD, Avila K, Bergsland EK, Chu P, Krieg RM, et al. Optimal timing of surgery after chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer: preliminary results of a multicenter, nonrandomized phase II prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2011;254(1):97–102. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182196e1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grass F, Behm KT, Duchalais E, Crippa J, Spears GM, Harmsen WS, et al. Impact of delay to surgery on survival in stage I-III colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(3):455–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.11.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Proscurshim I, Nunes Dos Santos RM, Kiss D, Gama-Rodrigues J, et al. Interval between surgery and neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for distal rectal cancer: does delayed surgery have an impact on outcome? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(4):1181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huntington CR, Boselli D, Symanowski J, Hill JS, Crimaldi A, Salo JC. Optimal Timing of Surgical Resection After Radiation in Locally Advanced Rectal Adenocarcinoma: An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(3):877–87. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4927-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong DH, Lee HB, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Kim NK. Optimal timing of surgery after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84(6):338–45. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.84.6.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaltenmeier C, Shen C, Medich DS, Geller DA, Bartlett DL, Tsung A et al. Time to Surgery and Colon Cancer Survival in the United States. Ann Surg. 2019. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003745. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Kammar P, Chaturvedi A, Sivasanker M, de’Souza A, Engineer R, Ostwal V, et al. Impact of delaying surgery after chemoradiation in rectal cancer: outcomes from a tertiary cancer centre in India. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;11(1):13–22. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.12.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaytan-Saglam E, Balik E, Saglam S, Akgun Z, Ibis K, Keskin M, et al. Delayed versus immediate surgery following short-course neoadjuvant radiotherapy in resectable (T3N0/N+) rectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(8):1597–603. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwak YK, Kim K, Lee JH, Kim SH, Cho HM, Kim DY, et al. Timely tumor response analysis after preoperative chemoradiotherapy and curative surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer: A multi-institutional study for optimal surgical timing in rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119(3):512–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefevre JH, Mineur L, Kotti S, Rullier E, Rouanet P, de Chaisemartin C, et al. Effect of Interval (7 or 11 weeks) Between Neoadjuvant Radiochemotherapy and Surgery on Complete Pathologic Response in Rectal Cancer: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial (GRECCAR-6) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(31):3773–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levick BA, Gilbert AJ, Spencer KL, Downing A, Taylor JC, Finan PJ, et al. Time to Surgery Following Short-Course Radiotherapy in Rectal Cancer and its Impact on Postoperative Outcomes. A Population-Based Study Across the English National Health Service, 2009-2014. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2020;32(2):e46–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim SB, Choi HS, Jeong SY, Kim DY, Jung KH, Hong YS, et al. Optimal surgery time after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancers. Ann Surg. 2008;248(2):243–51. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817fc2a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lino-Silva LS, Guzman-Lopez JC, Zepeda-Najar C, Salcedo-Hernandez RA, Meneses-Garcia A. Overall survival of patients with colon cancer and a prolonged time to surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119(4):503–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.25354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macchia G, Gambacorta MA, Masciocchi C, Chiloiro G, Mantello G, di Benedetto M, et al. Time to surgery and pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer: A population study on 2094 patients. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2017;4:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maliske S, Chau J, Ginader T, Byrn J, Bhatia S, Bellizzi A, et al. Timing of surgery following neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer: a retrospective analysis from an academic medical center. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(4):597–604. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mihmanli M, Kabul Gurbulak E, Akgun IE, Celayir MF, Yazici P, Tuncel D, et al. Delaying surgery after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy improves prognosis of rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8(9):695–706. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i9.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plastiras A, Sideris M, Gaya A, Haji A, Nunoo-Mensah J, Haq A, et al. Waiting Time following Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Rectal Cancer: Does It Really Matter. Gastrointest Tumors. 2018;4(3-4):96–103. doi: 10.1159/000484982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Probst CP, Becerra AZ, Aquina CT, Tejani MA, Wexner SD, Garcia-Aguilar J, et al. Extended Intervals after Neoadjuvant Therapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: The Key to Improved Tumor Response and Potential Organ Preservation. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(2):430–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rombouts AJM, Hugen N, Elferink MAG, Nagtegaal ID, de Wilt JHW. Treatment Interval between Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and Surgery in Rectal Cancer Patients: A Population-Based Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(11):3593–601. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roxburgh CSD, Strombom P, Lynn P, Gonen M, Paty PB, Guillem JG, et al. Role of the Interval from Completion of Neoadjuvant Therapy to Surgery in Postoperative Morbidity in Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(7):2019–27. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07340-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saglam S, Bugra D, Saglam EK, Asoglu O, Balik E, Yamaner S, et al. Fourth versus eighth week surgery after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy in T3-4/N0+ rectal cancer: Istanbul R-01 study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5(1):9–17. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2013.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SY, Guallar E, Hwang SS, Cho B, et al. Delay to curative surgery greater than 12 weeks is associated with increased mortality in patients with colorectal and breast cancer but not lung or thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(8):2468–76. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2957-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simunovic M, Rempel E, Theriault ME, Baxter NN, Virnig BA, Meropol NJ, et al. Influence of delays to nonemergent colon cancer surgery on operative mortality, disease-specific survival and overall survival. Can J Surg. 2009;52(4):E79–E86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sloothaak DA, Geijsen DE, van Leersum NJ, Punt CJ, Buskens CJ, Bemelman WA, et al. Optimal time interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(7):933–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Z, Adam MA, Kim J, Shenoi M, Migaly J, Mantyh CR. Optimal Timing to Surgery after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(4):367–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tran CL, Udani S, Holt A, Arnell T, Kumar R, Stamos MJ. Evaluation of safety of increased time interval between chemoradiation and resection for rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2006;192(6):873–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trepanier M, Paradis T, Kouyoumdjian A, Dumitra T, Charlebois P, Stein BS, et al. The Impact of Delays to Definitive Surgical Care on Survival in Colorectal Cancer Patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(1):115–22. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tulchinsky H, Shmueli E, Figer A, Klausner JM, Rabau M. An interval >7 weeks between neoadjuvant therapy and surgery improves pathologic complete response and disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(10):2661–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9892-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veenhof AA, Kropman RH, Engel AF, Craanen ME, Meijer S, Meijer OW, et al. Preoperative radiation therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: a comparison between two different time intervals to surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(5):507–13. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wanis KN, Patel SVB, Brackstone M. Do Moderate Surgical Treatment Delays Influence Survival in Colon Cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(12):1241–9. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolthuis AM, Penninckx F, Haustermans K, De Hertogh G, Fieuws S, Van Cutsem E, et al. Impact of interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and TME for locally advanced rectal cancer on pathologic response and oncologic outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):2833–41. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pettersson D, Cedermark B, Holm T, Radu C, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, et al. Interim analysis of the Stockholm III trial of preoperative radiotherapy regimens for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97(4):580–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eshuis WJ, van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, Bruno MJ, Kuipers EJ, et al. Therapeutic delay and survival after surgery for cancer of the pancreatic head with or without preoperative biliary drainage. Ann Surg. 2010;252(5):840–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fd36a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Healy GM, Redmond CE, Murphy S, Fleming H, Haughey A, Kavanagh R, et al. Preoperative CT in patients with surgically resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: does the time interval between CT and surgery affect survival? Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43(3):620–8. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirkegard J, Mortensen FV, Hansen CP, Mortensen MB, Sall M, Fristrup C. Waiting time to surgery and pancreatic cancer survival: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(10):1901–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marchegiani G, Andrianello S, Perri G, Secchettin E, Maggino L, Malleo G, et al. Does the surgical waiting list affect pathological and survival outcome in resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma? HPB (Oxford). 2018;20(5):411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mirkin KA, Hollenbeak CS, Wong J. Time to Surgery: a Misguided Quality Metric in Early Stage Pancreatic Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22(8):1365–75. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3730-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanjeevi S, Ivanics T, Lundell L, Kartalis N, Andren-Sandberg A, Blomberg J, et al. Impact of delay between imaging and treatment in patients with potentially curable pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103(3):267–75. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin SH, Han IW, Ryu Y, Kim N, Choi DW, Heo JS. Optimal timing of pancreaticoduodenectomy following preoperative biliary drainage considering major morbidity and postoperative survival. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26(10):449–58. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swords DS, Zhang C, Presson AP, Firpo MA, Mulvihill SJ, Scaife CL. Association of time-to-surgery with outcomes in clinical stage I-II pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with upfront surgery. Surgery. 2018;163(4):753–60. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teng A, Nguyen T, Bilchik AJ, O'Connor V, Lee DY. Implications of Prolonged Time to Pancreaticoduodenectomy After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation. J Surg Res. 2020;245:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brenkman HJF, Visser E, van Rossum PSN, Siesling S, van Hillegersberg R, Ruurda JP. Association Between Waiting Time from Diagnosis to Treatment and Survival in Patients with Curable Gastric Cancer: A Population-Based Study in the Netherlands. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(7):1761–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5820-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cha JH, Kim JH, Kim HI, Jung DH, Park JJ, Youn YH, et al. The optimal timing of additional surgery after non-curative endoscopic resection to treat early gastric cancer: long-term follow-up study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):18331. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54778-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujiya K, Irino T, Furukawa K, Omori H, Makuuchi R, Tanizawa Y, et al. Safety of prolonged wait time for gastrectomy in clinical stage I gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(10):1964–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Furukawa K, Irino T, Makuuchi R, Koseki Y, Nakamura K, Waki Y, et al. Impact of preoperative wait time on survival in patients with clinical stage II/III gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22(4):864–72. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-00910-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim MJ, Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim JW, Choi SH, Hyung WJ, et al. Is there an optimal surgery time after endoscopic resection in early gastric cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(1):232–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y, Zhang KC, Huang XH, Xi HQ, Gao YH, Liang WQ, et al. Timing of surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer: Impact on outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(2):257–65. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Foxtrot Collaborative Group Feasibility of preoperative chemotherapy for locally advanced, operable colon cancer: the pilot phase of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(11):1152–60. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70348-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seymour MT, Morton D, Foxtrot Collaborative Group FOxTROT: an international randomised controlled trial in 1052 patients (pts) evaluating neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for colon cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(15_suppl):3504. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.3504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Francois Y, Nemoz CJ, Baulieux J, Vignal J, Grandjean JP, Partensky C, et al. Influence of the interval between preoperative radiation therapy and surgery on downstaging and on the rate of sphincter-sparing surgery for rectal cancer: the Lyon R90-01 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Furukawa H, Iwata R, Moriyama N. Growth rate of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: initial clinical experience. Pancreas. 2001;22(4):366–9. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, Asbun H, Bain A, Behrman SW, et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(8):1028–61. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Datta SK, Belini G, Singh M, Papenfuss WA, Sanchez FA, Guda N, et al. Survival outcomes between surgery with adjuvant therapy compared to neoadjuvant therapy with surgery in stage I pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Results from a large national cancer database. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(4_suppl):335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tsukuma H, Oshima A, Narahara H, Morii T. Natural history of early gastric cancer: a non-concurrent, long term, follow up study. Gut. 2000;47(5):618–21. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]