Abstract

Purpose of review

Elastin has historically been described as an amorphous protein that functions to provide recoil to tissues that stretch. However, evidence is growing that elastin’s role may not be limited to biomechanics. In this minireview, we will summarize current knowledge regarding vascular elastic fibers, focusing on structural differences along the arterial tree and how those differences may influence the behavior of affiliated cells.

Recent findings

Regional heterogeneity, including differences in elastic lamellar number, density and cell developmental origin, plays an important role in vessel health and function. These differences impact cell-cell communication, proliferation, and movement. Perturbations of normal cell-matrix interactions are correlated with human diseases including aneurysm, atherosclerosis, and hypertension.

Summary

While classically described as a structural protein, recent data suggest that differences in elastin deposition along the arterial tree have important effects on heterotypic cell interactions and human disease.

Keywords: Elastin, elastic fibers, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells

Introduction

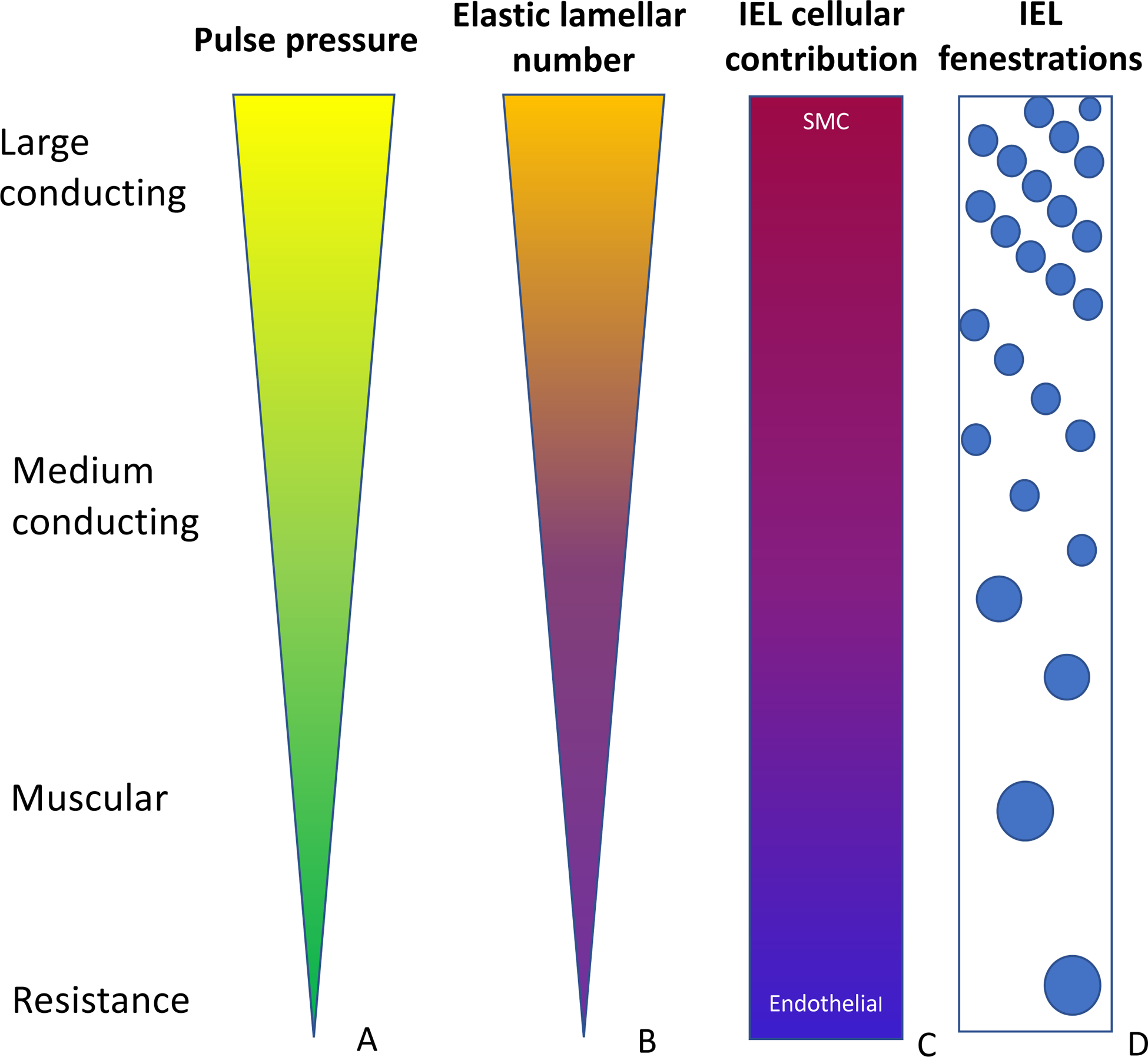

Mature elastic fibers, composed mainly of elastin, provide the elastic recoil necessary for normal physiologic function of organs such as arteries, lungs and skin. Elastin’s primary function in the arterial system, particularly in elastic arteries, is to store energy during systole and release it during diastole, dampening the pulse pressure and allowing laminar blood flow to the microcirculation where oxygen and nutrient exchange occurs. Indeed, the amount of elastin present in arteries along the arterial tree reflects this function; in the ascending aorta for example, elastin accounts for 40–60% of its dry weight depending on the species(1). Hence, proximal conduit arteries, where pulse pressure is high, have numerous elastic lamellae separated by smooth muscle cells (SMCs), while muscular and resistance arteries only have an internal elastic lamina (IEL) that separates endothelial cells (ECs) in the tunica intima from SMCs of the media and a discontinuous external elastic lamina that separates the media from the adventitia (Figure 1 A and B).

Figure 1. Arterial organizational structure.

The ascending aorta receives the entire output from the heart, leading to it to experience high pulse pressures (A). Those pressures are dampened along the course of the arterial tree. Correspondingly, the number of elastic lamellae is highest in the proximal vessels and is reduced to only 1–2 in the smaller arteries (B). The ascending aortic IEL elastin is produced by smooth muscle cells with a small contribution from endothelial cells. In the periphery, however, endothelial cells produce the majority of the elastin (C). The IEL has small evenly spaced fenestrations in the proximal aorta. Further out, the fenestrations become larger and more sporadic (D).

As experimental methodologies evolved, so has our understanding of vascular elastic fibers. No longer are they viewed as inert physical structures or scaffolds; rather elastic fibers are now known to be active participants in the dynamic signaling that occurs between cells and their environment. In this minireview, we will summarize recent findings of regional heterogeneity of elastin along the arterial tree and will highlight the impact of these structural differences on health and disease.

Changes to the arterial wall in elastin insufficiency

That elastin is indispensable for vascular development has been recognized for over 20 years. The global deletion of the mouse elastin gene (Eln−/−) was shown to result in lethality of the mice within two days of birth(2). Without normal elastic lamellae, Eln−/− mice suffered luminal occlusion due to migration of medial SMCs into the subendothelial space(2). Sections from the Eln−/− aortas revealed ~2.5X more proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PNCA) positive cells and abnormal orientation of subendothelial SMCs, without obvious disruption of the endothelial layer. In mouse lines with some remaining elastin (the Eln+/− with 50% elastin(3) and the Eln−/−; ELN+/+ that has 30% of the wild-type [WT] amount of elastin due to the presence of a human ELN bacterial artificial chromosome transgene(4)), the lumen was smaller, but not fully obliterated, and the wall showed increased medial SMC layers. Parallel findings have been reported in humans with elastin insufficiency(3)—in this case additional elastic lamellae are noted in arteries throughout the body. The vessels have reduced caliber(5) and display increased stiffness(6). In humans, in addition to the global arterial vasculopathy described above, some individuals also present with focal areas of stenosis, most commonly in the supravalvular aorta and in the pulmonary arteries. Histology reveals the formation of a neointima consisting of irregularly shaped SMCs interspersed between sparse and irregular elastic fibers(5, 7, 8), in addition to the medial thickening. Studies in the Eln−/−; ELN+/+ mice showed that decreased circumferential growth contributes greatly to the luminal obstruction phenotype(9), but none of the global insufficiency models have produced focal arterial stenosis to the extent seen in human elastin insufficiency.

Contributions of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells to arterial elastic fibers

It is generally accepted that SMCs are the major elastin-producing cell in the vessel wall(10–12). While evidence for elastin production by ECs in culture has been reported(13–15), whether ECs contribute to the IEL in vivo has been controversial. Recently, Lin et al.(16) utilized the Cre/LoxP system to generate mice with specific deletion of Eln in either ECs or SMCs and assessed the effect of cell-specific elastin loss on arterial structure. Their findings point to complex differences in elastin deposition along the arterial tree. Unlike mice with global elastin deletion, mice lacking SMC-produced elastin lived until ~10–15 days old and manifested coarctation of the aorta, but did not completely occlude their aortas. The ascending aorta of these mice had a highly fragmented IEL, while the IEL of the descending thoracic aorta and all other smaller arteries examined appeared intact. This suggests that EC-derived elastin is sufficient for the production of an IEL along most of the vascular tree, while in the ascending aorta, SMC-derived elastin is necessary for IEL integrity. Whether this requirement is related to physical (higher pulse pressure in the ascending aorta) or biological (neural crest vs. mesenchymal origin of SMCs(17, 18)) differences along the arterial tree remains to be determined. Interestingly, when elastin was deleted from SMCs in this system, a neointima of SMC origin was observed in the ascending aorta(16). The neointima was reminiscent of what is seen in humans with elastin insufficiency and tended to occur in areas where the IEL was highly disrupted, indicating that the presence of an IEL provides a barrier for SMC proliferation and migration.

When elastin was deleted from ECs, elastic arteries (ascending aorta, descending thoracic aorta, common carotid artery, subclavian artery, iliac artery and internal thoracic artery) had an intact IEL, while smaller muscular (mesenteric artery, renal artery, inferior epigastric artery and femoral artery) possessed a thin and fragmented IEL(16). Taken together, these data suggest a gradient in which SMCs are primarily required for functional IEL production in proximal elastic arteries while ECs are predominantly responsible for the IEL in muscular/resistance arteries (Figure 1C). However, it is likely that both ECs and SMCs contribute to the IEL in both locations.

Heterogeneity in elastic fiber organization/structure along the arterial tree

In addition to variations in cellular contributions to elastic fibers along the arterial tree, evidence suggests that significant differences exist in elastic fiber structure within an arterial segment and along the arterial tree. In early scanning electron microscopy studies of the elastic fiber, Roach(19) noted that elastin in the IEL and luminal medial elastic lamellae of sheep thoracic aorta was organized as concentric fenestrated sheets, while it formed a fibrous network on the adventitial side. Similar observations have been made more recently in rodents using 3D confocal microscopy(20). When comparing canine IEL along different segments of the aorta, Song and Roach(21) noted that the IEL of the proximal descending thoracic aorta had a rough “felt-like” surface with uniformly distributed fenestrae or holes. The IEL became increasingly smooth with larger more randomly distributed fenestrae as it transitioned from the thoracic to the abdominal aorta and further to the iliac arteries (Figure 1D); the same was true for sheep, rabbits, and rodents(22–25).

Postnatal developmental changes in IEL fenestration size and density have been examined in conduit and muscular arteries. When comparing the carotid artery IEL of 3 week-old vs. 23 week-old rabbits, Wong and Langille(25) found that the fenestrae surface area increased from 11.3±0.7 μm2 at 3 weeks to 61.2±5.5 μm2 at 23 weeks. Similarly, the number of fenestrae increased with age. The density of fenestrae (i.e. fenestrae/mm2 vessel) decreased by 26% with age however, suggesting that the increase in fenestrae number did not keep up with vessel growth. Similar findings were observed in the iliac and renal arteries, although there was a greater decrease in fenestrae density (up to 70% in iliac arteries). Similar fenestrae increases in size and number with age have also been shown in rodent arteries(24, 26).

As one of the functions of the arterial system is to accommodate physiological demands, partly by sensing hemodynamic stress, the effect of shear stress or blood flow on IEL remodeling has been examined. In both rabbits and rodents, reducing shear stress by ligating the external carotid and hence decreasing blood flow in the ipsilateral common carotid artery resulted in smaller IEL fenestrae size without a change in number(25, 27). While increasing shear stress (carotid artery contralateral to the ligation) resulted in increased IEL fenestrae size in rabbits(25); it did not affect the IEL in rats(27). The discrepancy in IEL changes in response to high shear stress in rabbits vs. rats could be related to the duration of high shear stress exposure (5 weeks for the rabbits vs. 1 week for the rats), extent of blood flow increase with carotid artery ligation, or species differences. In addition to growth and hemodynamic factors, IEL fenestrae incidence is also, at least in part, genetically determined as arteries of different normotensive rat strains (Brown Norway, Long Evans, Sprague Dawley and Wistar) have differing IEL fenestrae numbers(28, 29).

EC-SMC-IEL interactions – lessons learned from different pathologies

The IEL forms a physical barrier between ECs of the intima and SMCs of the media, preventing diffusion of substances across the arterial wall. Fenestrae reduce this barrier. Penn and Chisolm showed that EC injury increased transmural uptake of horse radish peroxidase from the blood to the media of rat aorta in vivo(30). This permeability is important for EC-SMC interaction or myoendothelial signaling via soluble mediators such as vasoactive substances or mitogens as well as through direct contact between the cells, via gap junctions(31–36). While a cause-effect relationship has not been fully demonstrated, abnormalities in IEL fenestrae and SMC-EC communication have been noted in different disease states.

Aneurysms —

The first indication for the presence of abnormalities in elastic fibers in aneurysmal disease came from Campbell and Roach in 1981. They examined human cerebral arteries, which contain a single layer of elastin, the IEL, and showed that the diameter and density of fenestrations were larger at the apex of arterial bifurcations, where aneurysms tended to develop(37). Changes in elastic fiber fenestrations have also been quantified in mouse models of aneurysmal disease(38, 39). In general, fenestrae increased in size and number in aneurysmal vessels, however, there were regional differences where the proximal aorta and convex regions of the aorta showed the greatest increase in fenestrae density(38). While an in depth discussion of aneurysm pathophysiology is beyond the scope of this review, the identification of genes involved in heritable forms of aneurysms has perhaps shed the greatest light on how perturbations in elastic fiber structure and/or SMC contractility leads to vessel wall weakness and aneurysm development(40, 41). In particular, disruption of the physical connection between elastin projections and proteins on the neighboring SMCs, the so-called “elastin contractile unit,” due to genetic alterations in the proteins involved, may lead to an inability of the artery, particularly the thoracic aorta, to withstand the high pulse pressure, increasing aneurysm risk(41). It is important to note that disruption of elastin-contractile unit is unlikely to be the inciting event for all aneurysm development as mutations in genes involved in transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling have also been shown to lead to thoracic aortic aneurysms(42–44). Furthermore, absence of elastin (hence lack of elastin-contractile unit) in the Eln−/− mice led to aortic occlusion rather than dilation(2). These data point to the complexity of aneurysm pathophysiology and to the importance of cell-matrix interactions in maintaining arterial integrity.

Atherosclerosis —

Lipid accumulation in the arterial wall is an initial step in atherosclerotic plaque formation that starts early in life. Initially, lipid, particularly low density lipoprotein (LDL), accumulates in the subendothelial space where it is oxidized (oxLDL). OxLDL induces an inflammatory response in which peripheral monocytes and T cells are also recruited. This process stimulates SMCs to migrate from the media to the intima, where they proliferate and secrete ECM that contributes to atheroma formation (reviewed in (45)). Changes in elastic fiber structure are integral to the development of atherosclerotic plaques as migration of SMCs from the media to the intima requires the holes to be greater than 3–4 μm wide(46). Indeed, experimental models of hypercholesterolemia showed increased IEL fenestrae size in both elastic and muscular arteries, likely a result of elastolysis(47–49). Furthermore, increased plasma low density lipoprotein (LDL) resulted in medial LDL accumulation only when the IEL was damaged(50).

Hypertension —

Hypertensive remodeling of both resistance and elastic arteries has been described in animal models as well as in humans(51, 52). In small resistance arteries and arterioles, which play a major role in blood pressure regulation(53), remodeling leads to increased media-to-lumen ratio and is mediated by complex mechanisms involving growth, apoptosis, inflammation, fibrosis and chronic vasoconstriction(54). In large elastic arteries on the other hand, hypertension-associated remodeling involves collagen and fibronectin deposition and elastin fragmentation, leading to increased large artery stiffness(55, 56).

While it is clear that hypertension leads to vessel wall changes, evidence from genetic studies indicates that changes in elastin also affect blood pressure control. Global hemizygous loss of elastin in mice (Eln+/−) resulted in hypertension(3). Studies examining elastic fibers in other genetic models of hypertension, such as the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) model, showed that hypertension was associated with changes in the IEL of large and small arteries (stiffer elastin and smaller fenestrae) and these changes preceded arterial narrowing(57–61). Interestingly, the differences in IEL fenestrae size and number varied with age and vessel size as Sandow and colleagues showed that, at 3 weeks of age, SHR superior mesenteric arteries have larger hole width and hole density than the normotensive Wistar Kyoto Rats (WKY), however, at 28 weeks of age, hole size was similar but hole number was lower in SHR leading to reduced hole density(24).

In resistance arteries, where elastin content is low, cellular responsiveness to vasoactive substances and EC-SMC communication are thought play a very important role in determining vascular tone. Studies comparing several hypertensive and normotensive rodent models found no correlation between IEL fenestrae size and number and direct EC-SMC contact through myoendothelial gap junctions(24). Rather, changes in IEL fenestrae size and number were thought to alter sites of diffusion of vasoactive substances between ECs and SMCs leading to altered reactivity. Consistent with this, mesenteric artery reactivity studies in Eln+/− mice, showed impaired endothelial-dependent vasorelaxation to acetylcholine and increased contractility to the vasoconstrictive substances, angiotensin II and phenylephrine(62). These data highlight the effect of structural changes in elastin on cellular functions. It is interesting to note that, unlike the Eln+/− mice, mice with hemizygous SMC-specific deletion of elastin (SM-ElnF/+) were not hypertensive despite having large artery stiffness(16). This may be related to normal elastin deposition by ECs in SM-ElnF/+ resistance arteries(16). Ultrastructural and functional comparison of resistance arteries in the two models might prove insightful.

Conclusion

While often described as structurally amorphous, it is clear that elastin deposition and its contribution to organ function are highly complex, active processes with significant regional differences. Within the arterial system, SMCs were found to be important for IEL formation in the ascending aorta while ECs were mainly responsible for its deposition in resistance or muscular arteries. This regional heterogeneity extends beyond the molecule itself to other elastic fiber associated proteins(63). In addition to its structural heterogeneity, elastin serves varying roles along the arterial tree, which include maintaining vascular integrity to prevent neointimal formation and facilitating cell-cell communication by diffusion or direct contact through its fenestrae. Despite increasing complexity, understanding regional differences in elastin assembly and function during development and disease conditions will be important to develop new therapeutic strategies.

Key points:

Elastin is an important component of the arterial wall, providing elastic recoil and facilitating local cell communication and movement.

The internal elastic lamina is generated by predominantly by smooth muscle cells in the ascending aorta and endothelial cells in the more peripheral arteries, but contributions from both cell types are probably present in all locations. Fenestrations of the elastic lamina also vary in size and number along the tree.

Regional characteristics of elastic lamellae contribute to a range of inherited and acquired vascular conditions.

Acknowledgments:

Financial support and sponsorship: BAK was supported by funding from the NHLBI Division of Intramural Research. CMH was supported by NIH grant K08HL135400.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References:

- 1.Neuman RE, Logan MA. The determination of collagen and elastin in tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1950;186(2):549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li DY, Brooke B, Davis EC, et al. Elastin is an essential determinant of arterial morphogenesis. Nature. 1998;393(6682):276–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li DY, Faury G, Taylor DG, et al. Novel arterial pathology in mice and humans hemizygous for elastin. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;102(10):1783–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirano EKR, Sugitani H, Ciliberto CH, Mecham RP. Functional rescue of elastin insufficiency in mice by the human elastin gene: implications for mouse models of human disease. Circulation Research. 2007;101(5):523–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins RT 2nd. Cardiovascular disease in Williams syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30(5):609–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozel BA, Danback JR, Waxler JL, et al. Williams syndrome predisposes to vascular stiffness modified by antihypertensive use and copy number changes in NCF1. Hypertension. 2014;63(1):74–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Son JA, Edwards WD, Danielson GK. Pathology of coronary arteries, myocardium, and great arteries in supravalvular aortic stenosis. Report of five cases with implications for surgical treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(1):21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards JE. Pathology of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction. Circulation. 1965;31:586–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiao Y, Li G, Korneva A, et al. Deficient Circumferential Growth Is the Primary Determinant of Aortic Obstruction Attributable to Partial Elastin Deficiency. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2017;37(5):930–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faris B, Tan OT, Toselli P, Franzblau C. Long-term neonatal rat aortic smooth muscle cell cultures: a model for the tunica media of a blood vessel. Matrix. 1992;12(3):185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giro MG, Hill KE, Sandberg LB, Davidson JM. Quantitation of elastin production in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells by a sensitive and specific enzyme-linked immunoassay. Coll Relat Res. 1984;4(1):21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruckman JL, Luvalle PA, Hill KE, et al. Phenotypic stability and variation in cells of the porcine aorta: collagen and elastin production. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 1994;14(2):135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantor JO, Keller S, Parshley MS, et al. Synthesis of crosslinked elastin by an endothelial cell culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;95(4):1381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carnes WH, Abraham PA, Buonassisi V. Biosynthesis of elastin by an endothelial cell culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;90(4):1393–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mecham RP, Madaras J, McDonald JA, Ryan U. Elastin production by cultured calf pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1983;116(3):282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin CJ, Staiculescu MC, Hawes JZ, et al. Heterogeneous Cellular Contributions to Elastic Laminae Formation in Arterial Wall Development. Circulation research. 2019;125(11):1006–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **This study uses the Cre/Lox system to delete elastin from endothelial or smooth muscle cells, highlighting heterogeneity in elastin production along the arterial tree and its impact on disease.

- 17.Majesky MW. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2007;27(6):1248–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawada H, Rateri DL, Moorleghen JJ, et al. Smooth Muscle Cells Derived From Second Heart Field and Cardiac Neural Crest Reside in Spatially Distinct Domains in the Media of the Ascending Aorta-Brief Report. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2017;37(9):1722–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roach MR. The pattern of elastin in the aorta and large arteries of mammals. Ciba Found Symp. 1983;100:37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clifford PS, Ella SR, Stupica AJ, et al. Spatial distribution and mechanical function of elastin in resistance arteries: a role in bearing longitudinal stress. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2011;31(12):2889–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song SH, Roach MR. Comparison of fenestrations in internal elastic laminae of canine thoracic and abdominal aortas. Blood Vessels. 1984;21(2):90–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roach MR, Song SH. Arterial elastin as seen with scanning electron microscopy: a review. Scanning Microsc. 1988;2(2):994–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Megens RT, Reitsma S, Schiffers PH, et al. Two-photon microscopy of vital murine elastic and muscular arteries. Combined structural and functional imaging with subcellular resolution. Journal of vascular research. 2007;44(2):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandow SL, Gzik DJ, Lee RM. Arterial internal elastic lamina holes: relationship to function? J Anat. 2009;214(2):258–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong LC, Langille BL. Developmental remodeling of the internal elastic lamina of rabbit arteries: effect of blood flow. Circulation research. 1996;78(5):799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez JM, Briones AM, Starcher B, Conde MV, et al. Influence of elastin on rat small artery mechanical properties. Exp Physiol. 2005;90(4):463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo ZY, Yan ZQ, Bai L, et al. Flow shear stress affects macromolecular accumulation through modulation of internal elastic lamina fenestrae. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2008;23 Suppl 1:S104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capdeville M, Coutard M, Osborne-Pellegrin MJ. Spontaneous rupture of the internal elastic lamina in the rat: the manifestation of a genetically determined factor which may be linked to vascular fragility. Blood Vessels. 1989;26(4):197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osborne-Pellegrin MJ. Natural incidence of interruptions in the internal elastic lamina of caudal and renal arteries of the rat. Acta Anat (Basel). 1985;124(3–4):188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penn MS, Chisolm GM. Relation between lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial cell injury and entry of macromolecules into the rat aorta in vivo. Circulation research. 1991;68(5):1259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Wit C, Hoepfl B, Wolfle SE. Endothelial mediators and communication through vascular gap junctions. Biol Chem. 2006;387(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Little TL, Xia J, Duling BR. Dye tracers define differential endothelial and smooth muscle coupling patterns within the arteriolar wall. Circulation research. 1995;76(3):498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Resnick N, Collins T, Atkinson W, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor B chain promoter contains a cis-acting fluid shear-stress-responsive element. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(10):4591–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandow SL, Hill CE. Incidence of myoendothelial gap junctions in the proximal and distal mesenteric arteries of the rat is suggestive of a role in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated responses. Circulation research. 2000;86(3):341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandow SL, Tare M, Coleman HA, et al. Involvement of myoendothelial gap junctions in the actions of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circulation research. 2002;90(10):1108–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sosa-Melgarejo JA, Berry CL. Intercellular contacts in the media of the thoracic aorta of rat fetuses treated with beta-aminopropionitrile. J Pathol. 1991;164(2):159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell GJ, Roach MR. Fenestrations in the internal elastic lamina at bifurcations of human cerebral arteries. Stroke. 1981;12(4):489–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez-Guimet J, Andilla J, Loza-Alvarez P, Egea G. High-Resolution Morphological Approach to Analyse Elastic Laminae Injuries of the Ascending Aorta in a Murine Model of Marfan Syndrome. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee VS, Halabi CM, Hoffman EP, et al. Loss of function mutation in LOX causes thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113(31):8759–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milewicz DM, Regalado E. Heritable Thoracic Aortic Disease Overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, et al. , editors. GeneReviews((R)) Seattle (WA)1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milewicz DM, Trybus KM, Guo DC, et al. Altered Smooth Muscle Cell Force Generation as a Driver of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2017;37(1):26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis F, Rateri DL, Daugherty A. Aortic aneurysms in Loeys-Dietz syndrome - a tale of two pathways? The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124(1):79–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallo EM, Loch DC, Habashi JP, et al. Angiotensin II-dependent TGF-beta signaling contributes to Loeys-Dietz syndrome vascular pathogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124(1):448–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacFarlane EG, Parker SJ, Shin JY, et al. Lineage-specific events underlie aortic root aneurysm pathogenesis in Loeys-Dietz syndrome. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2019;129(2):659–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emini Veseli B, Perrotta P, De Meyer GRA, et al. Animal models of atherosclerosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;816:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sims FH. Discontinuities in the internal elastic lamina: a comparison of coronary and internal mammary arteries. Artery. 1985;13(3):127–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Augier T, Charpiot P, Chareyre C, et al. Medial elastic structure alterations in atherosclerotic arteries in minipigs: plaque proximity and arterial site specificity. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 1997;15(7):455–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwon HM, Sangiorgi G, Spagnoli LG, et al. Experimental hypercholesterolemia induces ultrastructural changes in the internal elastic lamina of porcine coronary arteries. Atherosclerosis. 1998;139(2):283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakatake J, Yamamoto T. Three-dimensional architecture of elastic tissue in athero-arteriosclerotic lesions of the rat aorta. Atherosclerosis. 1987;64(2–3):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith EB, Staples EM. Distribution of plasma proteins across the human aortic wall--barrier functions of endothelium and internal elastic lamina. Atherosclerosis. 1980;37(4):579–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Briet M, Schiffrin EL. Treatment of arterial remodeling in essential hypertension. Current hypertension reports. 2013;15(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. The structural factor of hypertension: large and small artery alterations. Circulation research. 2015;116(6):1007–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mulvany MJ, Aalkjaer C. Structure and function of small arteries. Physiological reviews. 1990;70(4):921–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Intengan HD, Schiffrin EL. Vascular remodeling in hypertension: roles of apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2001;38(3 Pt 2):581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Briet M, Collin C, Karras A, et al. Arterial remodeling associates with CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(5):967–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung AW, Yang HH, Kim JM, et al. Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in the arterial vasculature contributes to stiffening and vasomotor dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2009;120(9):792–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arribas SM, Briones AM, Bellingham C, et al. Heightened aberrant deposition of hard-wearing elastin in conduit arteries of prehypertensive SHR is associated with increased stiffness and inward remodeling. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2008;295(6):H2299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boumaza S, Arribas SM, Osborne-Pellegrin M, et al. Fenestrations of the carotid internal elastic lamina and structural adaptation in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;37(4):1101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Briones AM, Gonzalez JM, Somoza B, et al. Role of elastin in spontaneously hypertensive rat small mesenteric artery remodelling. J Physiol. 2003;552(Pt 1):185–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohuet G, Challande P, Osborne-Pellegrin M, et al. Mechanical strength of the isolated carotid artery in SHR. Hypertension. 2001;38(5):1167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gonzalez JM, Briones AM, Somoza B, et al. Postnatal alterations in elastic fiber organization precede resistance artery narrowing in SHR. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2006;291(2):H804–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osei-Owusu P, Knutsen RH, Kozel BA, et al. Altered reactivity of resistance vasculature contributes to hypertension in elastin insufficiency. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2014;306(5):H654–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halabi CM, Broekelmann TJ, Lin M et al. Fibulin-4 is essential for maintaining arterial wall integrity in conduit but not muscular arteries. Sci Adv. 2017;3(5):e1602532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]