Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to analyze the role of global self-esteem and professional burnout in predicting Polish nurses’ quality of life.

Materials and Methods

The research involved 1806 nurses who were employed in 23 hospitals in north-eastern Poland. Forty-seven percent of nurses, aged ≤44 years, were qualified to Group 1, while 53% of nurses, aged ≥45 years, were included in Group 2. A diagnostic survey was applied as a research method. For the collection of data, the WHOQoL-Bref questionnaire, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and the Copenhagen Professional Burnout Inventory were used. For the statistical analysis, the significance level of P < 0.05 was adopted.

Results

Global self-esteem had a positive orientation towards the prediction of the quality of life among the younger nurse group in the psychological and social domains by explaining 20% (ßeta = 0.33; R2 = 0.20) and 15% (ßeta = 0.28; R2 = 0.15) of the result variation, respectively. In the older nurse group, personal burnout, which took a negative orientation in the somatic (ßeta = −0.33 R2 = 0.19), social (ßeta = −0.37; R2 = 0.17) and environmental domains (ßeta = −0.28; R2 = 0.32), had the greatest share in predicting the quality of life.

Conclusion

There is a need for the implementation of professional burnout prevention programs, as professional burnout adversely affects the quality of life in the somatic, social and environmental domain, particularly in the older nurse group.

Keywords: global self-esteem, professional burnout, quality of life, nurses

Introduction

Working as a nurse creates opportunities for development and fulfilment in the professional sphere as well as provides a sense of satisfaction, which is a subjective element of the quality of life. Despite many years of growing interest in the concept of the quality of life, researchers have not yet developed a uniform definition of this term.1 Angus Campbell, one of the first scholars to study the quality of life, points out that its definition should include the level of satisfaction with, among others, family and professional life, neighborly relations, social relations, health condition, ways of spending leisure time, education acquired, profession performed and general standards affecting the quality of life within a given local community.1,2 According to the position of the World Health Organization (WHO), the quality of life is defined as an individual’s perception their life position in the context of culture and the system of values in which they live, and in relation to the tasks, expectations and standards determined by environmental conditions.3 Human development and socialization are based on work, and work-related quality of life can be described as the physical and mental perception by an employee of working conditions and workplace factors.4,5 The work environment of nurses is characterized by multiple hazardous and harmful factors, inherent to the work process and related to the working conditions and requirements. Those conditions and factors include, among others, working hours, remuneration, the physical condition of the work environment, career path and interpersonal relations.4,5 The work of a nurse is related to specific professional functions that determine the type of tasks and activities performed. However, constant contact with people requiring support, attention and special care in the disease makes this work particularly stressful and mentally exhausting.6 Mental workload has a significant impact on health, well-being and career development plans, generating negative emotions and dissatisfaction with work.7,8 Low levels of personal and professional satisfaction result in employees quitting their jobs, which becomes an additional source of stress for other staff members.9,10 In turn, the well-being of health care workers is positively correlated with job satisfaction and motivation.11 In the recent decades, there has been a trend in research on the work environment toward assessing both the direct and indirect effects of psychosocial risk factors on health through stress mechanisms.12 As Bańkowska reports, “a stress-inducing work environment in health care establishments may result in the appearance of symptoms of professional burnout in some of the staff”.13 The research proves the link between the work environment, together with requirements posed at work, and the occurrence of burnout.14–16 Due to the specific nature of work and the profile of individual units, the level of professional burnout in nurses is not uniform.17 Moreover, it is linked to numerous socio-demographic variables. As results from the literature review, the age, marital status, length of service and number of children can be of crucial importance for identifying high-risk groups.17–20 Christina Maslach, a pioneer in burnout research, defines professional burnout as a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, de-personalization and reduced personal accomplishment which can occur in persons working with other people in a certain way.21 As she claims, it most frequently affects nurses, teachers, doctors, police officers and social workers.21 In reviewing various concepts of burnout, the current study adopted a view that has been defined in the European context by Kristensen et al.22 These Danish researchers developed a tool to measure occupational burnout, referred to as the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI). It is used to examine three main burnout components, identified as personal burnout, work-related burnout and client-related burnout.22 Personal burnout is described by the scholars as “physical and mental fatigue and exhaustion experienced by a given person”, work-related burnout as “physical and mental fatigue and exhaustion experienced by a given person while performing work” and client-related burnout, demonstrated as “physical and mental fatigue and exhaustion experienced by a given person in contacts with clients”.22 CBI has been gaining popularity in the recent years in the research on burnout among medical staff, as studies carried out, among others, in Canada,23 Norway,24 Australia,25,26 New Zealand27 and Poland.28–30 This proves that burnout is a worldwide problem, as it has been recently included in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Issue (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon.31 The analysis of the research literature shows that despite many years of scientific investigations, the mechanism through which multiple factors lead to the emergence of the burnout syndrome has not been fully explained.12 It is known, however, that each individual has their own personal resources which are beneficial to health. Research shows that this function is served by global self-esteem which, in a broad sense, describes the person’s self-image (which is associated with their overall well-being), the emotions being experienced and the approach to tasks.32,33 This determines an individual’s activity level and also shows strong ties with personality traits; moreover, not only is it associated with the emotional, but also with the executive, aspect of functioning.32 In 1965, Morris Rosenberg, a sociology professor at Maryland University, developed a proprietary scale which allows the general self-esteem level to be measured.34 When defining self-esteem, Rosenberg assumes that people have different attitudes towards various objects, and one’s Self is one of these objects.34 In Rosenberg’s view, high self-esteem is the conviction that one is “good enough”, a valuable person, while low self-esteem means dissatisfaction with oneself and a kind of rejection of one’s own self.32,34 By its very nature, self-esteem is a subjective construct based on the perception and assessment of oneself.32,35 There are theoretical premises and empirical evidence that global self-esteem can be measured as a feature as well as a state.36 The term “global self-esteem” is often used interchangeably with the term “self-esteem” which is also considered to be a one-dimensional construct.37 It is also worth referring to the results of a study conducted in 53 countries using the Big Five personality model, which proved that global self-esteem correlated negatively with neuroticism, and positively with extraversion as well as moderately or poorly with openness to experience.38 An important variable related to the quality of life is self-esteem. An attempt to empirically analyze the concept of self-esteem from the perspective of her professional career as a nurse was made by Christina Doré. She claims that the important attributes which enable the deeper understanding of the self-esteem concept include “self-value, self-acceptance, self-efficacy, attitude towards oneself and, finally, self-respect”.39 On the other hand, Li X et al analyzed the relationships between self-esteem and professional burnout syndrome among Chinese nurses and concluded that nurses with higher self-esteem reported a lower level of emotional exhaustion and cynicism and a higher level of professional effectiveness.40

It can be assumed that both global self-esteem and the experienced symptoms of professional burnout, as well as selected socio-demographic variables, modify the intensity of the nurses’ sense of the quality of life, in accordance with the model presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A model of relationships between variables

According to the presented theoretical assumptions for the analyzed variables ie professional burnout and global self-esteem, the aim of this study was to investigate to what extent they would play an important role in predicting the quality of life among nurses in the younger and older age groups.

The following research problems were formulated through scientific investigations:

To what extent does the age determine the quality of life, global self-esteem and personal burnout at work and in contacts with patients among the nurses under study?

What is the role of global self-esteem and personal burnout at work and in contacts with patients, and selected socio-demographic variables in predicting the quality of life among nurses in the younger and older age group?

Materials and Methods

Settings and Design

Empirical material was collected from June 2013 to January 2015. The survey was conducted among medical personnel (nurses/midwives) in 23 hospitals located in north-eastern Poland after obtaining the management team’s approval. Detailed descriptions of the baseline dataset has been published extensively elsewhere.28,29 One of the researchers (E.K.) provided the hospitals in which the research project was being implemented with sets of research instruments, including the authors’ original questionnaire containing questions about the socio-demographic data, the WHOQoL-Bref questionnaire, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES) questionnaire, and the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI). Participation in the study was voluntary. The respondents were informed about the aim of the study, had the opportunity to ask questions and obtain explanations, and had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason. After giving their consent for participation in the study, the respondents were provided with a set of questionnaires to be completed, which were returned from all hospitals within 5 days. The survey took approx. 30 minutes. A total of 2885 questionnaire form sets were distributed. After the collection of data and elimination of incomplete questionnaires, 1806 (ie 62.6%) questionnaires correctly completed by nurses were qualified for further analysis. The return percentage varied depending on the hospital, and ranged from 25.3 to 87.5%. The collected empirical material was encoded using a computer program, and the study results were analyzed on a collective basis.

The study was conducted in line with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Senate Research Ethics Committee of Olsztyn University College J. Rusiecki (No 11/2016), Poland. The study meets the cross-sectional criterion,41 and the empirical data used in the study are part of a larger research project under implementation in Polish hospitals.28,29

Participants

Detailed descriptions of the baseline dataset has been published extensively elsewhere.21,22 The median of 45 years for both groups was used as the determinant to divide the group under study into two age groups. 848 (47%) nurses, aged ≤44 years, were qualified to Group 1, while 958 (53%) nurses, aged ≥45 years, were included in Group 2 (Table 1). The data show that more than ¾ of the respondents in both age groups are married people (Group 1 = 76.8% vs Group 2 = 79.7%). The vast majority of the nurses worked two shifts, including night duties (1 = 83.6% vs Group 2 = 68.7%). Less than half of all the respondents (42.9%) claimed that their financial situation was sufficient. 27.4% of respondents in the younger age group and 45.2% in the older age groups had secondary education (completed medical high school). In the course of the analysis being conducted using the Chi-squared independence test (χ2), a statistically significant difference was observed between socio-demographic variables in both age groups, ie marital status (χ2 = 56.29; p < 0.001), education (χ2 = 151.36; p < 0.001), place of residence (χ2 = 40.03; p < 0.001), job position category (χ2 = 29.55; p < 0.001) and the shift work system (χ2 = 54.45; p < 0.001). Only for the financial situation was no statistically significant difference between groups noted. Detailed data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization of Socio-Demographic Variables in the Groups Under Study

| Variables | N=1806 | Test Value χ2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1≤44 Years n = 848 (47%) | Group 2 ≥45 Years n = 958 (53%) | ||||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 118 (13.9) | 50 (5.2) | 56.29 | 0.001*** |

| Married | 651 (76.8) | 763 (79.7) | |||

| Widowed | 6 (0.7) | 32 (3.3) | |||

| Divorced | 73 (8.6) | 113 (11.8) | |||

| Education | Secondary medical | 232 (27.4) | 433 (45.2) | 151.36 | 0.001*** |

| Vocational/post-secondary | 128 (15.1) | 243 (25.4) | |||

| 1st degree higher - Bachelor of Nursing | 295 (34.8) | 163 (17.0) | |||

| 2nd degree higher - Master of Nursing | 142 (16.7) | 72 (7.5) | |||

| Other type of higher education, applicable in healthcare units | 51 (6.0) | 47 (4.9) | |||

| Place of residence | Village | 211 (24.9) | 163 (17.0) | 40.03 | 0.001*** |

| City < 50,000 inh. | 243 (28.7) | 398 (41.5) | |||

| City 50,000–99,999 inh. | 107 (12.6) | 87 (9.1) | |||

| City ≥100 000 | 287 (33.8) | 310 (32.4) | |||

| Financial situation | Very good | 24 (2.8) | 24 (2.5) | 1.82 | n.s. |

| Good | 277 (32.7) | 290 (30.3) | |||

| Sufficient | 359 (42.3) | 415 (43.3) | |||

| Poor | 153 (18.0) | 183 (19.1) | |||

| Very poor | 35 (4.1) | 46 (4.8) | |||

| Job position category | Managerial | 55 (6.5) | 138 (14.4) | 29.55 | 0.001*** |

| Executive/unit nurse | 793 (93.5) | 820 (85.6) | |||

| Work system | Single-shift | 139 (16.4) | 300 (31.3) | 54.45 | 0.001*** |

| Multiple-shift | 709 (83.6) | 658 (68.7) | |||

Note: ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: N, total size of the examined population; n, size of the subset.

Research Instruments

The study applied the diagnostic survey method, and for the data collection, the following research instruments were used:

The authors’ original survey questionnaire, which included questions concerning the socio-demographic data, ie the age, marital status, education, place of residence, financial situation, the length of service, job position category and the work system.

The Quality of Life Questionnaire – a version of the WHOQoL-Bref adopted for Polish conditions by L. Wołowicka and K. Jaracz.42

The Self-Esteem Scale (SES) developed by M. Rosenberg and adopted for Polish conditions by I. Dzwonkowska, K. Lachowicz-Tabaczek and M. Łaguna.32

The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) developed by T.S. Kristensen et al.22

WHOQoL-Bref Questionnaire

The WHOQoL-Bref questionnaire is an abridged version of the WHOQoL-100 questionnaire, developed by a group of WHO life quality researchers. It consists of 26 questions and provides a quality of life profile in four domains of functioning: somatic, psychological, social (social relations) and functioning in the environment. It also contains two questions which assess satisfaction with the overall life quality and satisfaction with overall health quality. The respondents provided answers based on a 5-point Likert scale (the scoring range was from 1 to 5, where 1 = very dissatisfied and 5 = very satisfied). In each domain, the respondent could score a maximum of 20 points. The scores for particular domains have a positive orientation (ie the more points, the higher quality of life). The questionnaire has good psychometric properties; the reliability of the Polish version of the WHOQoL-Bref questionnaire is similar to that of the original version. The obtained α-Cronbach coefficient should be considered as very high, both in the assessment of particular domains (scores from 0.69 to 0.81) and the entire questionnaire (0.90).42

M Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The Rosenberg SES Scale enables the measurement of the overall level of overt global self-esteem considered to be a relatively stable attitude towards one’s self. It is comprised of 10 statements, all of which are diagnostic in nature. The respondent referred to each statement and indicated the extent to which they agreed with it. Answers were given using a four-point scale ranging from 1 = definitely agree to 4 = definitely disagree. When calculating the results, the scores for statements 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7 were reversed. The score was the total number of points which indicated the overall self-esteem level. The range of scores that could be obtained was from 10 to 40 points. The higher the score, the higher the self-esteem. The scale has good psychometric properties and is characterized by both high reliability and validity (the α-Cronbach coefficient for the women from the standardization group was 0.81; for men, it was 0.81–0.83). In normalization tests, sten standards for men and women were developed.32

The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory

The CBI questionnaire comprises 19 items which describe the respondent’s feelings about their professional work. It enables the evaluation of three professional burnout domains, ie personal burnout (6 questions), work-related burnout (7 questions) and patient-related burnout (6 questions). According to the questionnaire guidelines, the order of questions was changed, and the term “client” was replaced by “patient”. The respondent could choose one of the five possible answers and score a certain number of points according to the following adopted pattern: always or to a very large extent = 100 points; often or to a large extent = 75 points; sometimes or a little = 50 points; rarely or to a small extent = 25 points; never/almost never or to a very small extent = 0 points. For one question (11) concerning work-related burnout, a reversed score was applied: always or to a very large extent = 0 points; often or to a large extent = 25 points; sometimes or a little = 50 points; rarely or to a small extent = 75 points; never/almost never or to a very small extent = 100 points. The total score in each of the three burnout domains is determined by the average value obtained from particular parts. The questionnaire has good psychometric properties; the α-Cronbach coefficient relating to the evaluation of particular burnout domains is very high and ranges from 0.85 to 0.87.22,28,29

Statistical Analysis

The data generated during an a posteriori study were subjected to statistical analysis using the Polish version of STATISTICA 13 (TIBCO, Palo Alto, CA, USA), similarly to previous studies.28,29 For the result analysis, the following statistical methods were applied: measures of location and measures of variation to describe the population structure; the Chi-squared test of independence (χ2); the ANOVA (F) test - to assess the variation of the values of analyzed traits in the two distinguished sub-groups; the effect power measure (eta-squared η2); a multiple regression analysis in order to develop a model of random variable estimation from explanatory variables. The interpretation of the power of correlation between variables was based on the Guilford classification.43 The overall self-esteem index was converted into standardized units which were interpreted in accordance with the characteristics of the sten scale which contains 10 units and has a scale interval of 1 sten. The scores ranging from 1 to 4 stens were regarded as low, those ranging from 5 to 6 as average, and those ranging from 7 to 10 as high.32 For all tests, the significance level p < 0.05 was adopted.

Results

Overall Characteristics of Global Self-Esteem and Professional Burnout

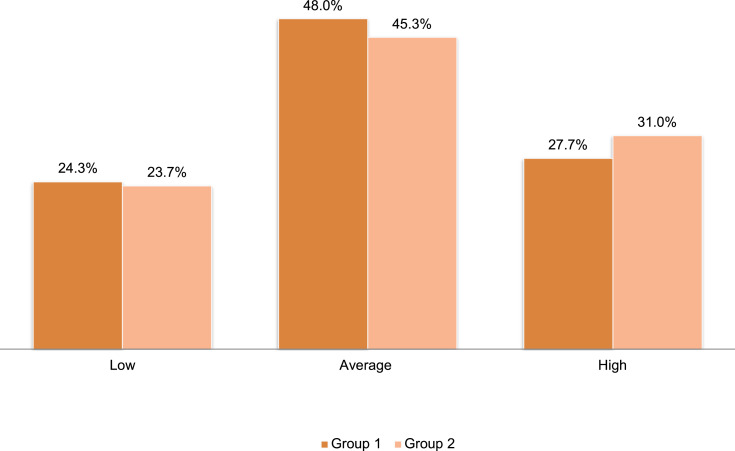

An analysis of the data collected using the Polish version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES) revealed that 27.7% of nurses from the younger group and 31.0% of nurses from the older age group had a high level of general overt self-esteem regarded as a state reflecting the level of social approval and acceptance being experienced. Having analyzed the measurement of self-esteem in the analyzed group as a trait which changes throughout a person’s life, both in the short and long term, it can be concluded that in nurses, it can be unstable and affect their functioning with different levels of global self-esteem. On the other hand, 24.3% of nurses from the younger group and 23.7% of nurses from the older age group achieved scores indicating low self-esteem according to the Rosenberg scale, which translates into dissatisfaction with oneself and is reflected as the rejection of one’s self. It can, therefore, be concluded that nurses with low self-esteem avoid difficult experiences and tend to withdraw from risky activities. The structure of global self-esteem scores on the Standard Ten scale, obtained by the two distinguished groups, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of global self-esteem scores in the age groups under study

Subsequent statistical analyses reveal a diverse structure of professional burnout among the nurses under study. The scores provided in Table 2 show that in the younger age group, from 46.6% to 52.0% of the respondents indicated the lack of professional burnout symptoms in all three components. In the older nurse group, professional burnout symptoms were not indicated by 42.8% to 49.5% of the nurses. On the other hand, more than ¼ of the respondents from both Group 1 and 2 stated that they were at risk of professional burnout.

Table 2.

Characterization of the Components of Professional Burnout Among the Nurses Under Study

| Professional Burnout Component Structure | Group 1 ≤44 Years (n = 848) | Group 2 ≥45 Years (n = 958) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Personal burnout structure | ||||

| No burnout | 441 | 52.0 | 474 | 49.5 |

| Risk of burnout | 231 | 27.2 | 279 | 29.1 |

| Presence of burnout | 176 | 20.8 | 205 | 21.4 |

| Work-related burnout structure | ||||

| No burnout | 422 | 49.8 | 410 | 42.8 |

| Risk of burnout | 224 | 26.4 | 263 | 27.5 |

| Presence of burnout | 202 | 23.8 | 285 | 29.8 |

| Patient-related burnout structure | ||||

| No burnout | 395 | 46.6 | 412 | 43.0 |

| Risk of burnout | 237 | 28.0 | 250 | 26.1 |

| Presence of burnout | 216 | 25.5 | 296 | 30.9 |

Abbreviation: n, size of the subset.

The presence of personal burnout symptoms in Group 1 was indicated by 20.8% (n = 176) of the respondents; slightly more nurses reported symptoms of work-related burnout (23.8%; n = 216) and patient-related burnout (25.5%; n = 216). In the older age group, as many as 30.9% (n = 296) of the respondents indicated that they experienced symptoms related to physical and emotional exhaustion in contacts with patients, while 29.8% (n = 285) reported symptoms of professional work-related burnout and 21.4% (n = 205) symptoms of personal burnout. Detailed data are provided in Table 2.

Diversity in the Quality of Life, Global Self-Esteem and Professional Burnout in the Groups Under Study – A Comparative Analysis

In a few cases, the statistical analysis demonstrated the occurrence of statistically significant differences in the results in terms of the respondents’ age. Having analyzed the nurses’ quality of life, significant differences in satisfaction with both the overall life quality (F = 5.05; p < 0.02) and the overall health quality (F = 22.60; p < 0.001) was found among the nurses from Group 1 and Group 2 (Table 3). The differences between the results appeared to be more advantageous for the nurses from the younger age group (≤ 44 years). Apparently, the younger nurses, as compared to the older nurses, exhibited greater satisfaction and rated the overall life and health quality higher. However, the differences (even though statistically significant) between these measurements were insignificant. This is evidenced by the eta-squared index value for satisfaction with the overall life quality (η2 = 0.003; 0.3%) and satisfaction with the overall health quality (η2 = 0.01; 1.0%). This, however, did not translate into the nurses’ sense of life quality in four domains of functioning, as no statistically significant differences were observed between the quality of life in Group 1 and Group 2 in the sphere of somatic, mental, social and environmental life. On the other hand, the average values for particular life quality domains in the analyzed groups varied. The social domain (concerning social relations) obtained the highest average values. In both groups, the average scores were at a similar level (15.40 ± 2.50 and 15.24 ± 2.43 points, respectively). Having referred the achieved scores to the specificity of nurses’ working environment, it can be concluded that they indicate the interpersonal nurses’ attitude characterized by a positive approach to the others and to oneself. Nurses from both the younger and the older age group rated both the psychological domain (14.15 ± 1.79; 14.01 ± 1.74) and the environmental domain (13.22 ± 2.26; 13.36 ± 2.21) slightly lower. However, the lowest average scores were obtained by the somatic domain which received scores at the same level for both Group 1 (12.66 ± 1.65) and Group 2 (12.79 ± 1.53). The lower scores obtained by the nurses under study in the environmental and somatic domains are probably linked to the subjective sense of the quality of life that refers to the functioning in the work environment in connection with performing specific tasks, functions and professional roles.

Table 3.

Diversity in the Quality of Life, Global Self-Esteem and Professional Burnout in the Groups of Nurses Under Study – A Comparative Analysis

| Variables | Group 1 ≤44 Years n = 848 | Group 2 ≥45 Years n = 958 | ANOVA (F) | p-value | The Effect Power Index (Eta-Squared) η2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | Me | Min. – Max. | M ± SD | Me | Min. – Max. | |||||

| Quality of life | Satisfaction with the quality of life | 3.57 ± 0.68 | 4 | 1–5 | 3.50 ± 0.66 | 4 | 1–5 | 5.05 | 0.02* | 0.003 |

| Satisfaction with the quality of health | 3.66 ± 0.71 | 4 | 1–5 | 3.49 ± 0.75 | 4 | 1–5 | 22.60 | 0.001*** | 0.01 | |

| Somatic domain | 12.66 ± 1.65 | 12.57 | 5.71–17.71 | 12.79 ± 1.53 | 12.57 | 7.43–18.19 | 3.00 | n.s. | 0.002 | |

| Psychological domain | 14.15 ± 1.79 | 14 | 7.33–19.33 | 14.01 ± 1.74 | 14 | 8.00–20.00 | 3.00 | n.s. | 0.002 | |

| Social domain (social relations) | 15.40 ± 2.50 | 15.40 | 6.67–20.00 | 15.24 ± 2.43 | 15.24 | 5.33–20.00 | 1.98 | n.s. | 0.001 | |

| Environmental domain | 13.22 ± 2.26 | 13.00 | 5.50–20.00 | 13.36 ± 2.21 | 13.50 | 6.00–20.00 | 1.79 | n.s. | 0.0009 | |

| Global self-esteem | 30.31 ± 3.33 | 30.00 | 13.00–40.00 | 30.48 ± 4.10 | 30.00 | 13.00–40 | 1.79 | n.s. | 0.0009 | |

| Burnout components | Personal burnout | 43.32 ±15.57 | 41.67 | 0.00–100.00 | 43.89 ± 16.10 | 45.83 | 0.00–95.83 | 0.58 | n.s. | 0.0003 |

| Work-related burnout | 45.06 ± 15.04 | 46.43 | 0.00–100.00 | 47.08 ± 15.60 | 46.43 | 0.00–92.86 | 7.85 | 0.005** | 0.004 | |

| Patient-related burnout | 45.02 ± 18.12 | 45.83 | 0.00–95.83 | 46.49 ± 18.34 | 45.83 | 0.00–95.83 | 2.95 | n.s. | 0.002 | |

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: M, mean; SD, standard deviation; Me, median; Min., minimum; Max., maximum; n.s., statistically insignificant.

Although subsequent analyses did not note significant differences in global self-esteem among the nurses under study, it was proven that there was a statistically significant diversity at the work-related burnout level (F = 7.85; p < 0.005). Nurses from the older age group (≥45 years) were characterized, to a lesser but statistically significant extent (p < 0.005), by a higher work-related burnout rate compared to younger nurses (≤44 years). This is also evidenced by the eta-squared index value (η2 = 0.004; 0.4%). The obtained results indicate that at individual stages of professional development, the first symptoms of professional burnout, eg body signals indicating chronic fatigue and weakness, should not be underestimated. According to the data presented in Table 3, no intergroup differences were noted at the nurses’ personal burnout and patient-related burnout levels.

The Predictors of Nurses’ Quality of Life

The next step of the conducted analyses was to determine the predictors of the studied nurses’ quality of life. When developing the multiple regression model, the following were adopted as explanatory variables: global self-esteem, personal burnout, work-related workout and patient-related burnout and socio-demographic variables which can be life quality determinants. Initially, the following were included in the socio-demographic variable pool: the marital status, the length of service, education, financial situation, shift work system and the job position type. Statistical analyses revealed that some of the variables had no significant effect on the regression model structure, while the financial situation, education and shift work system were taken into account as the socio-demographic variables that explain the nurses’ quality of life.

A regression analysis indicated that the predictors of the quality of life of nurses in Group 1 in the somatic domain were five variables which explained a total of 17% of the result variation (Table 4). Personal burnout had the greatest share (13%). The regression coefficient took on a negative value (ßeta = −0.30; R2 = 0.13) which indicated a negative dependency. The other variables, eg financial situation, global self-esteem, education and the shift work system explained the variation of the dependent variable results to a small extent (4%). On the other hand, the study results provided in Table 5 showed that the life quality predictors in the somatic domain in Group 2 were four variables which explained 25% of the result variation. The most important determinant appeared to be personal burnout (19%) which took on a negative orientation (ßeta = −0.33; R2 = 0.19). Another variable which explained the quality of life in the somatic domain was global self-esteem, although its predictive power was only 3%. The other variables, eg financial situation and the shift work system, explained a total of 3% of the result variation and were of little significance. The above-mentioned statistical analyses show that at a lower level of personal burnout, nurses from both the younger and the older age group indicate a higher sense of life quality in the somatic domain, which is characterized inter alia by the degree of need for medical treatment, the presence of physical pain, individual satisfaction as regards the daily performance at work and in everyday life, and satisfaction with sleep and rest.

Table 4.

Regression Summary – The Quality of Life of Nurses in Group 1 (≤ 44 Years)

| Variables | R2 | ßeta | ß | ß error | t | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (≤44 years) | |||||||

| Somatic domain | Personal burnout | 0.13 | −0.30 | −0.0 | 0.00 | −8.90 | 0.001*** |

| Financial situation | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 0.06 | 4.45 | 0.001*** | |

| Global self-esteem | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 3.05 | 0.001*** | |

| Education | 0.16 | −0.09 | −0.1 | 0.04 | −2.82 | 0.001*** | |

| Shift work system | 0.17 | −0.08 | −0.3 | 0.14 | −2.39 | 0.02* | |

| The unmarried status | 13.0 | 0.58 | 22.37 | 0.001*** | |||

| R = 0.41; R2 = 0.17; corrected R2 = 0.16 | |||||||

| Psychological domain | Global self-esteem | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 10.80 | 0.001*** |

| Personal burnout | 0.28 | −0.23 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −6.12 | 0.001*** | |

| Financial situation | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 5.74 | 0.001*** | |

| Patient-related burnout | 0.32 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.15 | 0.03* | |

| The unmarried status | 10.47 | 0.49 | 21.53 | 0.001*** | |||

| R = 0.56; R2 = 0.32; corrected R2 = 0.31 | |||||||

| Social domain (social relations) | Global self-esteem | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 8.82 | 0.001*** |

| Personal burnout | 0.22 | −0.24 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −5.30 | 0.001*** | |

| Financial situation | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 4.13 | 0.001*** | |

| Patient-related burnout | 0.25 | −0.19 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −3.70 | 0.001*** | |

| Work-related burnout | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.09 | 0.04* | |

| The unmarried status | 11.27 | 0.72 | 15.75 | 0.001*** | |||

| R = 0.50; R2 = 0.25; corrected R2 = 0.25 | |||||||

| Environmental domain | Financial situation | 0.24 | 0.41 | 1.05 | 0.07 | 14.67 | 0.001*** |

| Personal burnout | 0.36 | −0.22 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −5.33 | 0.001*** | |

| Global self-esteem | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 3.57 | 0.001*** | |

| Work-related burnout | 0.38 | −0.14 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −3.56 | 0.001*** | |

| The unmarried status | 10.63 | 0.59 | 18.06 | 0.001*** | |||

| R = 0.62; R2 = 0.38; corrected R2 = 0.38 | |||||||

Notes: *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: R, correlation coefficient; R2, multiple determination coefficient; ßeta, standardized regression coefficient; B, non-standardized regression coefficient; Error B, non-standardized regression coefficient error; t, t test value.

Table 5.

Regression Summary – The Quality of Life of Nurses in Group 2 (≥45 Years)

| Variables | R2 | ßeta | ß | ß error | t | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 2 (≥45 years) | |||||||

| Somatic domain | Personal burnout | 0.19 | −0.33 | −0.0 | 0.00 | −10.77 | 0.001*** |

| Global self-esteem | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 5.71 | 0.001*** | |

| Financial situation | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 5.29 | 0.001*** | |

| Shift work system | 0.25 | −0.08 | −0.3 | 0.10 | −2.74 | 0.01* | |

| The unmarried status | 11.9 | 0.48 | 25.05 | 0.001*** | |||

| R=0.50; R2=0.25; corrected R2=0.25 | |||||||

| Psychological domain | Global self-esteem | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 10.80 | 0.001*** |

| Personal burnout | 0.32 | −0.23 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −6.12 | 0.001*** | |

| Financial situation | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 5.74 | 0.03* | |

| The unmarried status | 10.47 | 0.49 | 21.53 | 0.001*** | |||

| R=0.58; R2=0.34; corrected R2=0.34 | |||||||

| Social domain (social relations) | Personal burnout | 0.17 | −0.37 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −8.14 | 0.001*** |

| Global self-esteem | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 8.94 | 0.001*** | |

| Financial situation | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 3.57 | 0.001*** | |

| Work-related burnout | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.37 | 0.02* | |

| The unmarried status | 11.22 | 0.69 | 16.14 | 0.001*** | |||

| R=0.50; R2=0.25; corrected R2=0.25 | |||||||

| Environmental domain | Personal burnout | 0.32 | −0.28 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −7.41 | 0.001*** |

| Financial situation | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 13.89 | 0.001*** | |

| Global self-esteem | 0.46 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 5.58 | 0.001*** | |

| Work-related burnout | 0.47 | −0.12 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.54 | 0.01* | |

| The unmarried status | 11.30 | 0.53 | 21.19 | 0.001*** | |||

| R=0.68; R2=0.47; corrected R2=0.47 | |||||||

Notes: *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: R, correlation coefficient; R2, multiple determination coefficient; ßeta, standardized regression coefficient; B, non-standardized regression coefficient; Error B, non-standardized regression coefficient error; t, t test value.

The predictors of the quality of life in the psychological domain in the younger nurse group were four variables which explained 32% of the result variation (Table 4). In predicting the quality of life in the psychological domain, global self-esteem had the greatest share (20%) by taking a positive orientation. In turn, the personal burnout component was a negative determinant and explained 8% of the result variation. The remaining variables had a small (not exceeding 4%) share in predicting the sense of life quality in the psychological domain. In the older nurse group, the predictors of the quality of life in the psychological domain in the nurses under study were three variables which explained 34% of the result variation of the dependent variable (Table 5). Similar to the younger nurse group, global self-esteem had the greatest share in predicting the quality of life in the psychological domain in the older age group (ßeta = 0.33; R2 = 0.23). The obtained results of the proprietary study suggest that a higher self-esteem experienced by nurses is correlated with the sense of a higher quality of life in the psychological domain, which is reflected by greater satisfaction in daily life. The nurses under study show a higher level of satisfaction with their appearance and less often experience negative feelings such as despondency, despair, anxiety or depression. Another variable with a negative input in predicting the quality of life in the psychological domain was personal burnout, which took a negative orientation and explained 9% of the result variation. On the other hand, financial situation explained a slight percentage (2%) of the dependent variable variation, and played no significant role in predicting the quality of life in the domain concerned.

The determinants of the quality of life in the social domain in the younger nurse group were five variables which explained a total of 25% of the result variation (Table 4). Global self-esteem, which explained 15% (ßeta = 0.28; R2 = 0.15) of the result variation, had the greatest share in predicting, while personal burnout explained 7%. The remaining variables, including patient-related burnout and work-related burnout, explained only 1% of the dependent variable variation, and played no significant role in predicting this particular domain of the quality of life. The situation in the older age group is slightly different. The regression analysis revealed that four variables, which explained a total of 25% of the result variation, participated in predicting the quality of life in the social domain in Group 2. Personal burnout had the greatest share in the prediction (ßeta = −0.37; R2 = 0.17) at a level of 17% of the dependent variable variation by taking the negative orientation. It can be concluded that with a lower rate of the emotional and physical fatigue and exhaustion symptoms, there is an increased probability of a higher quality of life linked to social relations (reflected inter alia by better relationships with other people, including the presence of support). Another variable with a considerably lower predictive power, but statistically significant to the quality of life in the social relation domain, was global self-esteem (6%). The other variables such as financial situation and work-related burnout explained the result variation to a small extent.

As indicated by the results provided in Table 4, the quality of life in the environmental domain in the younger nurse group was explained by four variables at a level of 38% of the dependent variable variation, and its significant predictor was the nurses’ financial situation, which explained 24% of the results (ßeta = 0.41; R2 = 0.24). It can be concluded that the nurses who believed that they were achieving an increasingly advantageous financial status also had a higher sense of the quality of life in the environmental domain. Personal burnout also appeared to be the second important prediction in this domain, as it took a negative orientation and explained 12% of the result variation. The other variables (global self-esteem and work-related burnout) had only a 2% share in explaining the result variation for the dependent variable. The results in this regard are slightly different in Group 2 (Table 5). The determinants of the quality of life in the environmental domain in the older nurse group were four variables which determined a total of 47% of the dependent variable’s variation. However, personal burnout, which took a negative orientation (ßeta = −0.28; R2 = 0.32) and indicated a negative dependency, had the most significant share (32%) in predicting the quality of life in the environmental domain. This means that at higher personal burnout rates, the nurses under study had a poorer perception of the aspects of life, eg safety, financial situation, an opportunity to pursue their interests, housing conditions and transportation. Another significant variable was the respondents’ financial situation which explained 12% of the dependent variable variation. The other variables explained only 3% of the result variation and played no significant role in predicting the nurses’ quality of life in the environmental domain. All of the constructed regression models were statistically significant.

Discussion

The authors of this study made an attempt to scientifically investigate, analyze and verify the relationship between global self-esteem, professional burnout and selected socio-demographic variables and the nurses’ quality of life, as the issue of the quality of life arouses many researchers’ interest and leaves many questions and doubts to be answered and resolved. The proprietary study results prove that, with age, Polish nurses exhibit varying satisfaction with the overall quality of life and health. After the age of 45, they rate them lower. Another study into the quality of life, conducted by Dugiel et al, demonstrated that the average result of the health assessment decreased gradually, according to the nurses’ age.44 The results obtained by Dugiel et al varied in terms of the studied nurses’ age and confirmed the higher quality of life in younger nurses compared to older ones.44 At this point, it is worth stressing that the respondents’ state of health, expressed through self-esteem, is of significant importance to the quality of life.45

As other studies have shown, quality of life is related to job satisfaction and can directly or indirectly affect the safety of patients and the quality of nursing care.46 A crucial element related to the improvement of nurses’ quality of life is social support. Kowitlawkul et al, who carried out a study in the group of 1040 nurses from Singapore, demonstrated that social support and the ability to cope with stress were the factors determining the high life quality of nurses. The researchers believe that cultivating social support provided by family, friends, colleagues and supervisors can help with stress management and improve nurses’ quality of life.46

An analysis of the average values, being part of the proprietary study, shows that the quality of life in the social domain was rated the highest by the nurses, while the somatic domain obtained the lowest scores both in the younger and the older nurse groups. For comparison, a study conducted by Lewko et al in a group of 523 Polish nurses obtained average values at a level very similar to the values obtained by the authors of this study for all the life quality domains also rated using the WHOQoL-Bref questionnaire.47

Another important issue analyze in the study was the assessment of the impact of global self-esteem on the shaping of the quality of life declared by the nurses under study. The results of proprietary research revealed that almost ¼ of the nurses under study, both from the younger and older age groups, were characterized by a low or high global self-esteem level. As shown by Baumeister et al, significant differences occurring between people with a high and low self-esteem determine the level of persistence and activity.35 People with a high self-esteem are more persistent in their actions, and engage in more various activities than people with a low self-esteem.35 An important issue in the proprietary research is the fact that global research is of positive significance in predicting the quality of life in both the younger and older nurse groups in the psychological and social domains. It can be concluded that as the global self-esteem increases, the nurses’ sense of the quality of life as regards the emotional and social functioning changes for the better. Therefore, the nurses cope better in difficult and stressful situations, and experience fewer negative emotions including, above all, sadness and anxiety. This thesis is also confirmed by the results of a study conducted by Yıldırım et al which demonstrated that self-esteem was linked to effective coping with stressful situations.47 When self-esteem increases, nurses are more active and socially efficient, and they exhibit a higher level of flexibility conducive to the effective performance of nurse’s tasks. This was confirmed in a study by Orth et al who found that self-esteem has a considerable prospective impact on actual life experiences, and a high self-esteem is associated with well-being and satisfaction.48 In the light of proprietary research, it is reasonable to take actions in the work environment to increase personal resources, including self-esteem, which has a beneficial effect on the sense of life quality and protects nurses against professional burnout. This is demonstrated by the results of numerous studies which confirm the relationship between self-esteem and professional burnout in nurses.49–52

An analysis of the literature shows that many researchers indicated the significant role of self-esteem in better coping with stress and overcoming difficulties in studying among nursing students.45,51 Huang et al conducted an interesting study on the positive relationship between empathy and self-esteem in 1690 Chinese medical students and proved that self-esteem explained 15.5% of the variation of empathy in the final regression model.53 Sturm & Dellert point out that the nurses’ sense of professional dignity has common features with self-esteem.54 Other researchers demonstrated that self-esteem has a direct and indirect effect on uncontrolled eating habits. Furthermore, self-esteem determines whether physical exercise is done to improve one’s image, recognition or social affiliation.55

In further research into the nurses’ quality of life, it may be assumed that self-esteem as an individual’s potential helps identify the strengths and weaknesses as regards the professional role. Proprietary study proved that a strong determinant which affects the perception of the quality of life is the professional burnout experienced by nurses as both physical and mental fatigue or exhaustion associated with the personal life sphere as well as with the work conditions and in contacts with patients. In this situation, it is reasonable to prepare and implement a prevention and/or intervention program as regards the prevention of professional burnout in employees. The key to early prevention is to identify risk factors and reorganize nursing care.56 After identifying the needs, the nursing managers should implement strategies increasing work motivation and help nurses to develop techniques to cope with high mental stress.57 De Oliviera et al reviewed the literature and pointed out that the following interventions were used in the prevention of professional burnout: yoga, cognitive coping strategies, compassion fatigue programs, systematic clinical supervision, meditation, web-based stress management programs and the Psychological Empowerment Program.57 The results of the current study confirm the advisability of the application of the above preventive measures in nurses.

The presented study has its advantages and limitations. The advantage is that this is the first study in Poland with such a broad range, and the obtained study results contribute to the better understanding of the issue of nurses’ quality of life while taking into account the role of global self-esteem and professional burnout. Since the study is cross-sectional, the presence of causal links between variables should be interpreted thoughtfully.

Implications for Nursing Practice

The study provides scientific evidence that can be used to develop and implement training programs which allow nurses to balance their professional and personal lives. The prevention and health promotion programs at the workplace should become a permanent component of managing nursing teams. It is recommended that nurses should have the opportunity to use a variety of methods and forms of in-company intervention and external training sessions. An example is individual and group supervision, which enables the acquisition of skills for assessing the situation in the work environment and developing one’s own individual resources. The systematic participation of nurses in external or internal training programs is intended to contribute to the development of nurses’ social competences as regards the building of emotional bonds with other people, respect for the dignity and autonomy of those entrusted to the care, empathy in relation with the patient and their family, and effective communication between colleagues.

Conclusions

As compared to the older nurses, the younger ones exhibited greater satisfaction and rated the overall life and health quality higher. No statistically significant differences in the quality of life in the somatic, psychological, social and environmental domains were, however, demonstrated in the age groups under study.

Nurses from the older age group were characterized, to a lesser (but statistically significant) extent, by a higher work-related burnout rate compared to younger nurses

No significant diversity in global self-esteem was noted among nurses in the age groups concerned.

In the younger age group, a positive role of global self-esteem in predicting the quality of life in the psychological and social domains was demonstrated. On the other hand, among the older nurses, global self-esteem was the determinant of the quality of life only in the psychological domain.

The nurses from the younger age group who believed that they were achieving an increasingly advantageous financial status, had a higher sense of the quality of life in the environmental domain.

In the older nurse group, a negative role of personal burnout in predicting the quality of life in the somatic, social and environmental domains was demonstrated.

Funding Statement

Collegium Medicum University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn covered the costs of publishing in open access. The research was implemented as part of the project (62-610-001).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kupcewicz E. Quality of life of nurses and strategies for coping with stress experienced in the work environment. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2017;23(1):62–67. doi: 10.5604/20834543.1235627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell A. The Sense of Well-Being in America: Recent Patterns and Trends. McGraw-Hill, NY; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL). Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahyaoglu SH, Mestogullari E. Effect of premenstrual syndrome on work-related quality of life in turkish nurses. Saf Health Work. 2016;7(1):78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YW, Dai YT, McCreary LL, et al. Quality of nursing work life scale. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16(3):298–306. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molero M, Pérez-Fuentes M, Gázquez JJ. Analysis of the mediating role of self-efficacy and self-esteem on the effect of workload on burnout’s influence on nurses’ plans to work longer. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper SL, Carleton HL, Chamberlain SA, et al. Burnout in the nursing home health care aide: a systematic review. Burnout Res. 2016;3(3):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2016.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Bogaert P, Peremans L, Van Heusden D, et al. Predictors of burnout, work engagement and nurse reported job outcomes and quality of care: a mixed method study. BMC Nurs. 2017;16(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0200-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamont S, Brunero S, Perry L, et al. Mental health day’ sickness absence amongst nurses and midwives: workplace, workforce, psychosocial and health characteristics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017;73(5):1172–1181. doi: 10.1111/jan.13212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvie K, Sidebotham M, Fenwick J. Australian midwives’ intentions to leave the profession and the reasons why. Women Birth. 2019;32(6):e584–e593. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cramer E, Hunter B. Relationships between working conditions and emotional wellbeing in midwives. Women Birth. 2019;32(6):521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manzano-García G, Ayala JC. Insufficiently studied factors related to burnout in nursing: results from an e-Delphi study. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bańkowska A. Burnout syndrome - symptoms and risk factors. Piel Pol. 2016;2(60):256–260. doi: 10.20883/pielpol.2016.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilczek-Różycka E, Zaczyk I, Obrzut K. Professional burnout of palliative care nurses. Piel Zdr Publ. 2017;26(1):77–83. doi: 10.17219/pzp/64031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leszczyński P, Panczyk M, Podgórski M, et al. Determinants of occupational burnout among employees of the Emergency Medical Services in Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2019;26(1):114–119. doi: 10.26444/aaem/94294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merces MC, Coelho JMF, Lua I, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout syndrome among primary health care nursing professionals: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(2):474. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gómez-Urquiza JL, Vargas C, De la Fuente EI, et al. Age as a risk factor for burnout syndrome in nursing professionals: a meta-analytic study. Res. Nurs. Health. 2017;40(Suppl. 2):99–110. doi: 10.1002/nur.21774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De la Fuente-solana EI, Suleiman-Martos N, Pradas-Hernández L, et al. Prevalence, related factors, and levels of burnout syndrome among nurses working in gynecology and obstetrics services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16(14):2585. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cañadas-de la Fuente GA, Ortega E, Ramírez-Baena L, et al. Gender, marital status and children as risk factors for burnout in nurses: a meta-analytic study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(10):2102. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suleiman-Martos N, Albendín-García L, Gómez-Urquiza JL, et al. Prevalence and predictors of burnout in midwives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(2):641. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, et al. The copenhagen burnout inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 2005;19(3):192–207. doi: 10.1080/02678370500297720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoll K, Gallagher J. A survey of burnout and intentions to leave the profession among Western Canadian midwives. Women Birth. 2018;32(4):e441–e449. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henriksen L, Lukasse M. Burnout among Norwegian midwives and the contribution of personal and work-related factors: a cross-sectional study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2016;9:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fenwick J, Lubomski A, Creedy D, et al. Personal, professional and workplace factors that contribute to burnout in Australian midwives. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018;74(4):852–863. doi: 10.1111/jan.13491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creedy D, Sidebotham M, Gamble J, et al. Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1212-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixon L, Guilliland K, Pallant J, et al. The emotional wellbeing of New Zealand midwives: comparing responses for midwives in caseloading and shift work settings. N Z Coll Midwives J. 2017;53:5–14. doi: 10.12784/nzcomjnl53.2017.1.5-14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kupcewicz E, Jóźwik M. Association of burnout syndrome and global self-esteem among Polish nurses. Arch Med Sci. 2019;16:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupcewicz E, Jóźwik M. Positive orientation and strategies for coping with stress as predictors of professional burnout among polish nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(21):4264. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nowakowska I, Rasińska R, Głowacka MD. The influence of factors of work environment and burnout syndrome on self-efficacy of medical staff. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(2):304–309. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1203895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11). The Global Standard for Diagnostic Health Information. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dzwonkowska I, Lachowicz-Tabaczek K, Łaguna M. Samoocena I Jej Pomiar. Polska Adaptacja Skali SES M. Rosenberga [Self-Esteem and Its Measurement. A Polish Adaptation of the M. Rosenberg SES Scale]. Poland: The Psychological Test Laboratory, Warszawa; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown JD, Marshall MA. The three faces of self-esteem In: Kernis MH, editor. Self-Esteem: Issues and Answers. NY Hove: Psychology Press; 2006:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg M. Society and Adolescent Self-Image. New York: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, et al. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2003;4(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Robins RW. Stability of self-esteem across the life span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(1):205–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mruk C. Defining self-esteem: an often overlooked issue with crucial implications In: Kernis MH, editor. Self-Esteem: Issues and Answers. NY Hove: Psychology Press; 2006:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(4):623–642. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doré C. Self-esteem: concept analysis. Rech Soins Infirm. 2017;17(129):18–26. doi: 10.3917/rsi.129.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Guan L, Chang H, et al. Core self-evaluation and burnout among Nurses: the mediating role of coping styles. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. STROBE initiative. strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1500–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaracz K, Kalfoss M, Górna K, et al. Quality of life in Polish respondents: psychometric properties of the Polish WHOQOL-Bref. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(3):251–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szymczak W. Podstawy Statystyki Dla Psychologów [Fundamentals of Statistics for Psychologists]. Poland: Difin, Warszawa; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dugiel G, Kęcka K, Jasińska M. Jakość życia pielęgniarek – badanie wstępne [Nurses’ quality of life - preliminary study]. Med Og Nauk Zdr. 2015;21(4):398–401. doi: 10.5604/20834543.1186913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibrahim NK, Alzahrani NA, Batwie AA, et al. Quality of life, job satisfaction and their related factors among nurses working in king Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52(4):486–498. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1224123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewko J, Misiak B, Sierżantowicz R. The Relationship between mental health and the quality of life of polish nurses with many years of experience in the profession: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1798. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yıldırım N, Karaca A, Cangur S, et al. The relationship between educational stress, stress coping, self-esteem, social support, and health status among nursing students in Turkey: a structural equation modeling approach. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;48:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orth U, Robins RW, Widaman KF. Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(6):1271–1288. doi: 10.1037/a0025558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manomenidis G, Kafikia T, Minasidou E, et al. Is self-esteem actually the protective factor of nursing burnout? IJCS. 2017;10:1348. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molero M, Pérez-Fuentes M, Gázquez JJ. Analysis of the mediating role of self-efficacy and self-esteem on the effect of workload on burnout’s influence on nurses’ plans to work longer. Front Psychol. 2018;9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santos SVMD, Macedo FRM, Silva LAD, et al. Work accidents and self-esteem of nursing professionals in hospital settings. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2017;20(25):e2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Badri Gargari R, et al. Self-esteem challenges of nursing students: an integrative review. Res Dev Med Educ. 2016;5(1):5–11. doi: 10.15171/rdme.2016.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang L, Thai J, Zhong Y, et al. The positive association between empathy and self-esteem in chinese medical students: a multi-institutional study. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1921. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sturm BA, Dellert JC. Exploring nurses’ personal dignity, global self-esteem and work satisfaction. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23(4):384–400. doi: 10.1177/0969733014567024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pérez-Fuentes MC, Molero Jurado MM, Simón Márquez MM, et al. The reasons for doing physical exercise mediate the effect of self-esteem on uncontrolled eating amongst nursing personnel. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):302. doi: 10.3390/nu11020302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu F, Xu Y, Yu Y, et al. Moderating effect of mindfulness on the relationships between perceived stress and mental health outcomes among chinese intensive care nurses. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:260. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Oliveira SM, de Alcantara Sousa LV, Vieira Gadelha MDS, et al. Prevention actions of burnout syndrome in nurses: an integrating literature review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2019;15(1):64–73. doi: 10.2174/1745017901915010064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]