Abstract

Permanent integration of the viral genome into a host chromosome is an essential step in the life cycles of lentiviruses and other retroviruses. By archiving the viral genetic information in the genome of the host target cell and its progeny, integrated proviruses prevent curative therapy of HIV-1 and make the development of antiretroviral drug resistance irreversible. Although the integration reaction is known to be catalyzed by the viral integrase (IN), the manner in which retroviruses engage and attach to the chromatin target is only now becoming clear. Lens Epithelium-Derived Growth Factor (LEDGF/p75) is a ubiquitously expressed nuclear protein that binds to lentiviral IN protein dimers at its carboxyl terminus and to host chromatin at its amino terminus. LEDGF/p75 thus tethers ectopically expressed IN to chromatin. It also protects IN from proteosomal degradation and can stimulate IN catalysis in vitro. HIV-1 infection is inhibited at the integration step in LEDGF/p75-deficient cells, and the characteristic lentiviral preference for integration into active genes is also reduced. A model in which LEDGF/p75 acts to tether the viral preintegration complex to chromatin has emerged. Intriguingly similar chromatin tethering mechanisms have been described for other retroelements and for large DNA viruses. Here we review the evidence supporting the LEDGF/p75 tethering model and consider parallels with these other viruses

Keywords: chromatin, lentivirus, HIV-1, LEDGF/p75, tether, Herpesvirus, KSHV

Introduction

Reverse transcription of retroviral genomic RNA produces a cDNA copy that is subsequently integrated into the host cell DNA [1]. The resulting provirus is a permanent hereditable part of the infected cell’s genome. The viral integrase (IN), which catalyzes this reaction, enters the cell as part of the viral particle, which is believed to contain less than 100 IN molecules. IN is thus never substantially present as a free protein within the cell, since it is only cleaved from a larger polyprotein, the Gag/Pol precursor, when a nascent particle has been enclosed by envelope during or after budding at the plasma membrane. IN performs two biochemically similar, but spatially distinct transesterification reactions that lead to provirus formation [2, 3]. The first, 3’ processing, occurs in the cytoplasm where a dinucleotide is cleaved off the 3’ termini, leaving an invariant CA with a free OH group at each end of the cDNA. The second step, strand transfer, occurs at the host chromosome, where IN uses the 3’ OH groups to carry out concerted nucleophilic attacks on the target DNA at locations a few bases apart. The viral cDNA 3’ ends are then joined to host DNA. Unknown cell ligases repair the gapped intermediate to complete the integration reaction.

In vitro, purified retroviral IN is sufficient to mediate 3’ processing and strand transfer reactions between artificial DNA substrates [2]. The situation is more complicated in vivo, where integration occurs between the viral preintegration complex (PIC) and host chromatin. The PIC consists minimally of IN and the viral cDNA. Vpr, Matrix (MA), and nucleocapsid (NC) also remain after reverse transcription; it is not known which viral proteins besides IN persist in the nucleus to the point of integration [4]. Several host proteins have also been reported to be PIC components, such as barrier to autointegration (BAF[5]), high mobility group proteins (HMGs[6]) and LEDGF/p75 [7]. The timing in the viral life cycle, and location within the cell of their engagement by the PIC remain unclear. Host chromatin is a complex macromolecular assembly that undergoes rapid changes in both structure and composition [8, 9]. Among the numerous HIV-1 IN-interacting proteins described, LEDGF/p75 has now received the most virological, biochemical and structural study [10]. This nuclear protein, which is ubiquitously expressed and tightly chromatin associated, binds at its C-terminus to lentiviral IN protein dimers. The N-terminal half binds to chromatin [3, 7, 10–13]. The current model envisions LEDGF/p75 acting as a tether between host chromatin and the PIC. In this review we discuss the evidence for this model and consider it in the context of chromatin attachment mechanisms used by other viruses. We also discuss the potential for manipulation of the LEDGF/p75-IN interaction to facilitate site-specific integration by lentiviral vectors and to treat HIV-1 infection.

Integrase and retroviral integration

IN is synthesized as the most C-terminal segment of the Gag/Pol precursor, a large polyprotein that is cleaved by the viral protease to yield the main structural and enzymatic constituents of the retroviral particle. This proteolytic cleavage cascade, which is initiated by protease auto-excision, occurs simultaneously with, or shortly after particle budding. Three IN domains have been defined structurally and functionally; an N terminal domain (NTD, amino acids 1–50), a catalytic core domain (CCD, amino acids 50–212) and a C-terminal domain (CTD, amino acids 212–288). All three domains are involved in IN multimerization and DNA binding. The CCD of IN has an essential D,D-35-E motif characteristic of numerous polynucleotidyl transferases [2, 14]. A crystal structure for full length IN has yet to be achieved, but the structures of the NTD and CTD have been solved alone and as two-domain structures with the CCD [14–17]. The CCD forms a 5-stranded beta barrel sheet resembling that of transposases and RNAseH [18].

Local chromatin features including primary DNA sequence affect integration site selection [19]. Chromatin-bound proteins may either inhibit integration by sterically blocking IN, or facilitate integration by bending DNA [20]. It is now also clear that there is larger-scale selectivity, and newer high throughput DNA sequencing methods are permitting more detailed analysis of genome-wide retroviral integration site patterns [21, 22]. Significant differences exist between retroviral genera. Lentiviruses [23–25] favor insertion into active transcription units. Simple retroviruses like MLV integrate in and around promoters [26, 27]. Foamy viruses [28, 29] integrate close to CpG islands, and ASLV has the most random of all patterns [27]. At least for HIV-1 and MLV, the retroviral IN protein appears to confer the integration site preference, with Gag making a lesser contribution [30, 31]. The distinct integration patterns observed for each retrovirus suggest that their viral pre-integration complexes engage in unique chromatin interactions. For lentiviruses, LEDGF/p75 appears to be the mediator of chromatin attachment.

LEDGF/p75 is a bipartite molecular adaptor that tethers cellular proteins and lentiviral integrase proteins to chromatin

LEDGF/p75 is a 530 amino acid ubiquitously expressed, chromatin-associated protein [32]. As a member of the hepatoma derived growth factor (HDGF) family, LEDGF/p75 contains the characteristic N-terminal PWWP domain [33]. Alternative splicing of the gene (PSIP1) produces a 333 amino acid product called LEDGF/p52 [32, 34]. LEDGF/p75 is a modular protein with distinct N terminal and C-terminal domains that have discrete functions (see Figure 1). Deletion and domain transfer experiments identified an N-terminal domain ensemble (NDE) comprising of a PWWP domain and pair of AT hooks that cooperate to mediate chromatin attachment [35, 36]. While the AT hooks bind AT-rich DNA in vitro [36], the PWWP domain (which does not display in vitro DNA binding [36]) probably interacts with unknown protein ligands [3]. LEDGF/p75 remains tightly attached to chromatin throughout the cell cycle [7, 37–39], and this is resistant to Triton X-100 extraction, such that disruption with DNAse and salt treatment are required to release chromatin-bound LEDGF/p75 [35]. Transfer of Triton resistance to GFP requires the N-terminus of LEDGF/p75 comprising the PWWP, AT hooks, an NLS and additional charged (CR) domains [35]. It is unknown if, like other chromatin bound proteins (e.g., histones [40, 41], transcription factors [42, 43]) LEDGF/p75 has a rapid exchange rate. A conserved 82 amino acid C-terminal integrase binding domain (IBD), which is found only in LEDGF/p75 and one other HDGF family member, HRP-2, mediates IN binding [37, 44, 45]. LEDGF/p75 also binds multiple other cellular proteins at the IBD, suggesting that HIV-1 has co-opted a protein with a natural role in chromatin tethering [45–48]. These other binding partners are discussed further in the next section. LEDGF/p52 has transcriptional coactivator activity like LEDGF/p75 [32], but it does not appear to play a role in lentiviral biology since it lacks the IBD.

Figure 1:

A) Domain organization of LEDGF/p75. The N terminal domain ensemble (NDE) and the integrase binding domain (IBD) are indicated. The PWWP domain and AT hooks are the primary determinants of chromatin binding [35, 36]. However restoration of triton resistant chromatin attachment requires additional charged regions (CR2 and/or CR3) [35]. A transferable NLS was mapped to amino acids 146–156 [37, 38]. The IBD extends from amino acids 347 to 429 [37, 44]. This domain is present in one other HDGF member, HRP2, which binds IN in vitro [44], but does not appear to compensate for LEDGF/p75 deficiency in human cells [71].

B) LEDGF/p75 tethers lentiviral IN to chromatin

LH4 cells are 293T cells where LEDGF/p75 is knocked down by plasmid mediated shRNA, and stably express low levels of a myc tagged HIV-1 IN. IN is detectable in the cytoplasm of these cells (top panel). When LEDGF/p75 is re-expressed IN is stabilized [62], is exclusively nuclear, and is tethered to mitotic chromatin.

The cellular roles of LEDGF/p75 are incompletely understood. It has been suggested to function as a growth factor [49, 50], a stress factor [51–53], a survival factor [49, 54, 55] and a transcriptional co activator [32], with a role in homeobox gene regulation [56]; see [Llano M, Morrison J, and Poeschla EM. Virological and Cellular Roles of the Transcriptional Coactivator LEDGF/p75. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2009 (in press)] for a review. These disparate effects may reflect the diversity of proteins with which LEDGF/p75 interacts in transcriptional pathways. Recent reports have suggested that LEDGF/p75’s cellular functions have mechanistic parallels to its viral cofactor role, since it acts as a chromatin tether for various cellular proteins, including mixed lineage leukemia (MLL)/menin and JP02. The MLL gene encodes a histone methyltransferase, and is the target of translocation in several leukemias [57, 58]. The resultant oncogenic chimeric MLL proteins consist of the N-terminus of MLL fused to diverse partners. Menin, a nuclear tumor suppressor protein implicated in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) [57, 59], interacts with the N-terminus of MLL [57]. Loss of this binding abrogates the transforming activity of several MLL chimeras [60]. Overexpression of Menin and MLL in 293T cells led to the identification of LEDGF/p75 as a third binding partner in the complex [48, 61]. Both Menin and MLL are required for LEDGF/p75 copurification, and LEDGF/p75 interaction is necessary for leukemia induction. The sole role of LEDGF/p75 in the triad is to tether MLL to chromatin. For example, fusion of the PWWP domain of LEDGF/p75 directly to an MLL-ENL protein lacking the Menin binding site sufficed to attach this protein to chromatin and maintained its transforming activity, even though it could no longer bind either LEDGF/p75 or Menin [48].

Two groups identified the c-Myc binding protein JP02 as a LEDGF/p75 interactor [46, 47]. JP02 also binds to the LEDGF/p75 IBD, but the critical IBD contact amino acids differ from those required for IN binding. Mutation of Asp366 abrogates virtually all IN binding but does not affect not JPO2 interaction for example [47]. Also functionally analogous to IN [7, 62], JPO2 co-localizes with LEDGF/p75 on chromatin, and its steady state levels are stabilized by LEDGF/p75 binding [46].

A third cellular LEDGF/p75 interactor was recently identified by yeast 2 hybrid screening [45]. Using a C- terminal LEDGF/p75 fragment (amino acids 342–507) as bait, and a T cell cDNA library as prey, a domesticated transposase, pogZ was identified. Like IN, the D,D-35-E domain is the site of interaction. Unlike IN, JP02, and Menin/MLL, the interaction with LEDGF/p75 does not tether pogZ to condensed chromatin. This difference may be due to lesser affinity of pogZ for LEDGF/p75, and/or possibly competition in vivo from other binding partners. More speculatively, the pogZ interaction could suggest that IBD binding has been relevant to other retroelements in the past, but was only maintained in lentiviruses.

LEDGF/p75, IN and lentiviral infection

LEDGF/p75 was identified as an HIV-1 IN binding partner by co-immunoprecipitation from 293T cell nuclear extracts [10]. It was subsequently found to bind to multiple lentiviral but not other retroviral integrase proteins [7, 13, 63] HIV-1 and FIV integration-competent PICs have been immunoprecipitated with antibodies to LEDGF/p75 [7]. The role of this protein in the HIV-1 life cycle was recently comprehensively reviewed [3, 64]. Mutational analysis of HIV-1 IN identified Trp131/132, and residues 161–170 of the HIV-1 IN CCD as critical for LEDGF/p75 binding [65]. (IN residues 161–173 had earlier been invoked as a transferable karyophilic signal [66]; however, further studies have clarified that no NLS is present at this location [67, 68].) A crystal structure of the IN CCD complexed with the LEDGF/p75 IBD demonstrated that an unstructured loop of the IBD extends into a pocket formed by an asymmetrical IN dimer [12]. Consistent with mutational analyses of binding, LEDGF/p75 amino acids Ile365 and Phe406 form hydrophobic interactions with Ala128 and W131 of one IN monomer, whereas the carbonyl side chain of Asp366 forms a critical bidentate hydrogen bond with the backbone amides of Glu170 and His171 of the other IN monomer. Substitution of the Asp366 for either Ala or Asn abrogates the IBD-IN interaction in vitro and in cells [12, 69–71]. The structural importance of contacts made by the IN alpha 4–5 helices connector peptide backbone rather than amino acid side chain interactions with the IBD in this region help to explain the preservation of LEDGF/p75 interaction among all lentiviruses despite little direct sequence conservation in these dimer interface residues; a corollary implication is consistent functional selection pressure for LEDGF/p75 binding during the evolution of this retroviral genus. A recently solved structure for a two domain HIV-2 IN fragment (NTD plus CCD) complexed with the IBD revealed that negatively charged amino acids in the IN NTD also contribute to LEDGF/p75 binding by interacting with positively charged residues in the IBD [72] [39]. Moreover, complementary charge reversal mutations in the NTD and the IBD produced proteins that maintained interaction but abrogated WT LEDGF/p75 binding; the latter has potential to facilitate targeted lentiviral vector gene therapy by permitting engineered IN-LEDGF/p75 pairs that ignore abundant endogenous LEDGF/p75. While the initial efforts in this direction did not yield lentiviral vectors with adequate titer [72], this is an important concept that deserves further exploration.

When HIV-1 or FIV IN are over-expressed as free proteins, which again is an artificial maneuver without a direct correlate in the viral life cycle for this obligate PIC constituent, they can be seen to co-colocalize precisely with LEDGF/p75 at chromatin [7, 38]. (GFP-IN fusions behave somewhat aberrantly so that immunolabeling of small epitope-tagged IN or native IN is preferred for such studies). Knockdown of LEDGF/p75 leads to a striking re-localization of IN to the cytoplasm (see Figure 1B and [7, 37, 39]). Depletion of LEDGF/p75 from human or murine cells has several effects on the HIV-1 life cycle. First, it inhibits HIV-1 infection,from ten- to thirty-fold in single round reporter virus assays, with most of the block mapping to the integration step of the life cycle [71, 73–75]. The lentiviral preference for integrating into active transcription units is also reduced in LEDGF/p75 deficient cells [73, 75, 76], with a gammaretrovirus-resembling shift towards promoters. There is also a decrease in integration into AT-rich DNA and into LEDGF/p75-responsive genes. Rescue of HIV-1 infection to wild type levels requires that both the NDE and the IBD of LEDGF/p75 be functionally intact i.e., both chromatin and IN attachment capacity must be present [71, 73]. Re-introducing a LEDGF/p75 variant with specific amino acid mutations in the IBD (e.g., D366N) or combining mutations of the PWWP and AT hook domains, abrogate rescue [71, 73].

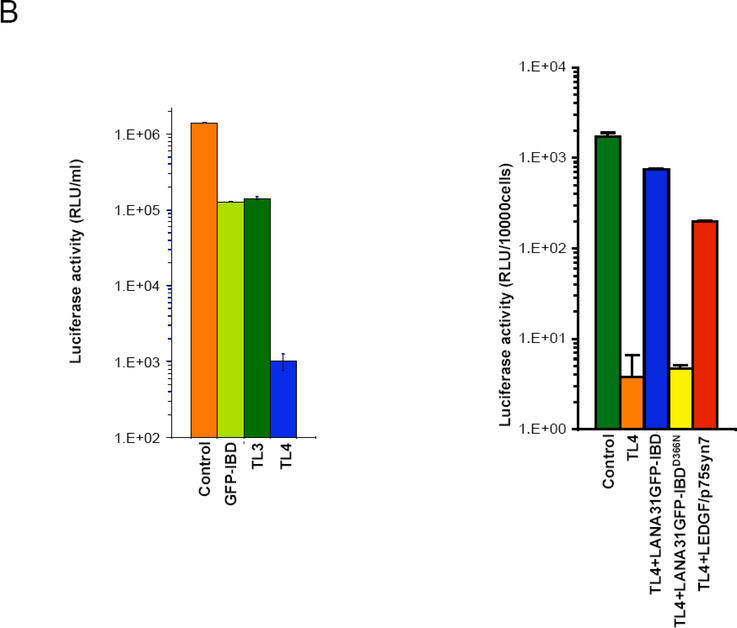

Over-expression of the IBD (as a GFP-IBD fusion protein) inhibits HIV-1 replication, with the degree of inhibition approximating that caused by LEDGF/p75 knockdown (Figure 2B left panel and [71, 77, 78]. Combining LEDGF/p75 knockdown with the dominant interfering GFP-IBD produces a strikingly effective multiplicative block, inhibiting single round infectivity by up to 4 logs ( Figure 2B left panel and [71], Meehan A, unpublished data. Serial passage of HIV-1 in the presence of such dominant-interfering mutant proteins leads to selection of IN escape mutants [78] (and Saenz et al., unpublished data).

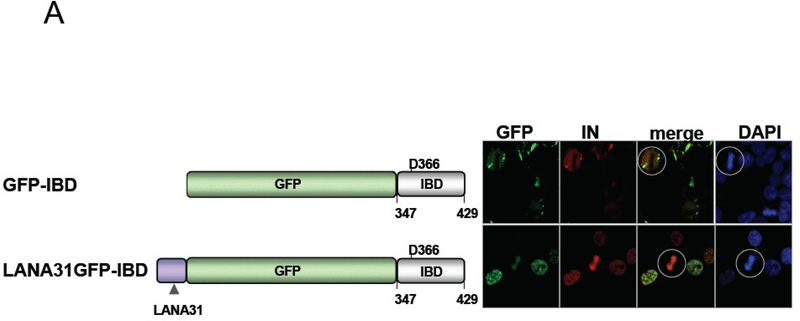

Figure 2:

A) Testing the tether hypothesis To recapitulate LEDGF/p75 cofactor function, an alternatively tethered IBD should minimally restore IN chromatin attachment. The N terminal 31 amino acids of LANA were fused to GFP-IBD, which contains only amino acids 347–429 of LEDGF/p75 [89]. LH4 cells (described in Figure 1) were transiently transfected with either GFP-IBD or LANA31-GFP-IBD, and the effect on IN localization was examined by immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy. In the top panel, GFP-IBD interacts with IN, forming discrete structures, but most of IN remains cytoplasmic. In contrast in the lower panel LANA31GFP-IBD binds IN, tethering it to chromatin even in mitotic cells (circled). Images from [89].

B) LEDGF/p75 IBD molecules with alternative chromatin tethers are functional lentiviral cofactors.

In the graph on the left, knockdown of LEDGF/p75 (TL3 cells) or expression of untethered GFP-IBD in SupT1 cells inhibits HIV-1 infection, and combining both is multiplicative (TL4 cells). The deficit in HIV-1 infection here is 3 logs. In contrast, as is seen on the graph on the right the tethered LANA31GFP-IBD restores HIV-1 infectivity by 2 logs, comparably to native LEDGF/p75. Both graphs modified from [89]. See [89] for additional data on the LEDGF/p75 knockdown rescuing properties of other LANA31 chimeras.

Whereas proper integration in vivo requires that both retroviral cDNA ends insert into the chromosome in a concerted fashion, attempts to recapitulate the reaction in vitro with model DNAs and purified recombinant IN proteins often produce aberrant insertion of a single cDNA terminus into only one strand of the target DNA [2]. LEDGF/p75 can stimulate the strand transfer component of lentiviral IN catalysis in vitro but the effects are disparate for different lentiviruses and have varied with particular conditions used [10, 36, 44, 63, 65, 72, 79–82]. The equivalent of concerted integration was strongly enhanced for EIAV IN, but for HIV-1 single end insertion was favored [63]. Additional factors may be required to achieve concerted HIV-1 integration in vitro. It should be noted in this regard that LEDGF/p75 stabilizes the tetrameric form of IN [81], and that in vitro, an IN dimer is sufficient for 3’ end processing, but a tetramer appears needed for DNA strand transfer activity [83–85]. In cells, LEDGF/p75 binds tetrameric IN [10]; see also Hare et al. 2009 for recent structural insights [72].

Lentiviral Integration: Evidence for the chromatin tethering requirement

Structure-function considerations suggest persistent strong selection for IN-LEDGF/p75 interaction during the evolution of the lentiviral genus, since the protein binds to all lentiviral IN proteins despite considerable intra-genus variation at actual key IN contact residues [7, 13, 37, 44, 63]. In contrast, LEDGF/p75 does not bind IN proteins of alpha-, beta-, delta and gamma- or spuma-retroviruses [7, 13, 63]. All lentiviruses also display similar integration site preferences, integrating into active genes [23–26, 86–88]. In LEDGF/p75-depleted cells, gene targeting is reduced substantially [73, 75, 76]. Both the N-terminal chromatin binding domain ensemble (NDE) and the integrase binding domain are required for LEDGF/p75 integration cofactor function [71, 89]. From these and other findings, a model of LEDGF/p75 acting as a molecular tether between PIC-associated IN and the chromatin fiber has emerged. It is possible that the assistance this factor provides extends to more than attachment, since as noted above LEDGF/p75 can also stimulate IN catalysis in vitro [10, 13, 36, 44, 63, 72, 79–82] and protects ectopically expressed IN from proteosomal degradation [62]. However, a LEDGF/p75 mutant lacking the PWWP domain and AT hooks, which is not chromatin attached yet still protects IN from proteosomal degradation, did not rescue HIV-1 infection in LEDGF/p75-depeleted cells [71, 73]. Similarly, HRP-2 is a nuclear protein that also binds IN via the IBD and retains ectopic IN in the nucleus of LEDGF/p75 deficient cells. However, it does not bind condensed chromatin and it does not rescue infection in human T cells [37, 71]. Thus, the chromatin attachment properties of LEDGF/p75 appear critical to its function as a viral cofactor. This role may be primary [3], fitting a scenario where pre-integration complex attachment per se rather than a need for LEDGF/p75 to cofactor IN catalysis was the primary evolutionary driver for LEDGF/p75 dependency during lentivirus evolution. Thus, while as noted above the strand transfer component of IN catalysis is augmented in vitro in the presence of LEDGF/p75, this effect would not be surprising under either scenario, since it could reflect secondary adaptation to the IBD as a structural bulwark at the inter-dimer cleft. Finally, the connection LEDGF/p75 establishes could serve to sterically position the IN-complexed viral cDNA ends at an optimal orientation and distance to the chromosomal DNA target, in which case one might expect that wholesale alteration of the NDE would disrupt integration.

In recent work we tested these questions, asking whether integration requires chromatin tethering per se, specific NDE-chromatin ligand interactions or other emergent properties of LEDGF/p75. We replaced the NDE of LEDGF/p75 with structurally and functionally divergent alternative chromatin attachment protein modules, i.e., two variants of the human linker histone H1 and a 31 amino acid peptide (LANA31) derived from the N-terminus of Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV) latency associated nuclear antigen (LANA) [90] (see Fig. 2A). The rationale was as follows. H1 and LANA31 differ strongly in natural role, evolutionary origin, size, structure and the nature of their chromatin ligands. H1 binds outside the nucleosome, to DNA, while LANA31 binds inside the nucleosome core, to protein. H1 binds the DNA between nucleosomes, condensing chromatin and facilitating higher order structure formation [91, 92]. The C-terminus has numerous basic amino acids that bind DNA nonspecifically [93, 94]. For LANA31, the goal was to adapt the known strategy of a DNA virus. KSHV is a gammaherpes virus associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma and multicentric Castleman disease [90, 95]. Like other herpes viruses, KSHV can establish latent infection in certain cells, where the viral DNA persists as an episome [96]. LANA is a large viral protein that mediates attachment of the circular DNA episome to chromatin, by binding to both terminal repeat (TR) elements in the viral genome, and a groove formed between core histones 2A and 2B [90]. However, the first 30 amino acids of LANA contains the entire histone 2A/histone 2B binding sequence (amino acids 5–13) [90]. Interestingly, substitution of the DNA binding domains of LANA with histone 1 can impart KSHV episome persistence [97]

When they were introduced into LEDGF/p75-deficient cells, H1 and LANA31 chimeras rescued LEDGF/p75 cofactor activity [89]. Some of the results we obtained for LANA31 chimeras are recapitulated in Fig. 2. To reconstitute LEDGF/p75 chromatin-tethering, chimeric IBD proteins need at the minimum to bind chromatin and IN and also tether IN to chromatin throughout the cell cycle. These criteria were met (Fig. 2A). Strikingly, simply tethering GFP-IBD to chromatin via LANA 31 changes it from a potent integration blocker to an integration facilitator, rescuing HIV-1 infectivity by 2 logs (Fig. 2B right panel). This reversal of functional properties imparted by the LANA31 peptide provides substantial evidence that tethering per se is the primary LEDGF/p75 cofactor function.

Why do lentiviruses use a tether?

Why would a secure, and cell cycle-continuous chromatin attachment mechanism be important for a retrovirus? While the problem of PIC nuclear import in non-dividing cells has been a consistent conundrum [4, 98, 99], a more general problem exists that was recognized to be both important and unsolved a decade ago:

MLV integration does not appear to occur during mitosis, but rather after mitosis is completed [98]. Thus, access to the nuclear DNA, provided by the breakdown of the nuclear membrane at mitosis, is not in itself sufficient to account for localization of the viral genome to the nucleus after the nuclear membrane reassembles [100, 101]. The mechanism by which the pre-integration complex ensures that it is retained in the nucleus when the nuclear envelope is reassembled is not yet known.[102]

Thus, one possibility relates to the survival of PICs during the cell cycle. For example, it is known that transfected plasmid DNA is excluded from daughter nuclei after mitosis [103]. Recent nuclear structure/function studies suggest dynamic mobility of chromatin, even in interphase [8]. In addition, the virus must avoid sequestration by other nuclear components. Chromatin undergoes extreme condensation during the cell cycle [8, 9], a physical compaction that might impede PIC integration. Unless it can achieve chromatin attachment that is both secure and cell cycle-persistent, the retroviral pre-integration complex may be at risk of attrition from dynamic nuclear processes that may include but are not limited to specific host defense mechanisms.

LEDGF/p75 not only provides a means for a lentivirus to attach to chromatin, but to do so at transcriptionally advantageous loci. The protein’s abundance and function as a transcriptional coactivator with a role in the general transcription machinery can thus be seen as ideal characteristics for the virus. Genome wide integration site profiling supports this model. In LEDGF/p75 deficient cells, lentiviruses behave more like simpler gammaretroviruses, integrating in and around promoters rather than into active transcription units [73, 75, 76, 104]. A default retroviral mechanism targeting promoters thus appears to be overridden by the LEDGF/p75 interaction. An interesting prediction is that HIV-1 integration will be more random in the cell lines with LANA31 and H1 chimeric tethers, since, unless other chromatin features interfere, they are predicted to bind equivalently to every nucleosome. Such studies are in progress (Meehan A, data not shown).

Parallels to other viruses

Latency is a characteristic of a number of double-stranded DNA viruses such as the Herpesviridae and Papillomaviridae. Unlike lentiviruses, herpeviruses do not integrate, and formation of a protein tether is not a prelude to establishing permanent covalent bonds with host chromosomes. Nevertheless, they do utilize similar strategies to establish stable chromatin linkages, which enables them to persist as circular DNA episomes that segregate reliably with the nuclear DNA during cell division [95, 105]. The EBNA-1 protein of Epstein Barr virus binds to chromatin throughout mitosis. Binding is mediated at least in part by one and perhaps more AT hook motifs [105], although interaction with EBP2 protein may also play a role [106].The C -terminus of EBNA dimerizes on a specific 30-bp dyad DNA sequence that occurs repeatedly in the OriP of the episome. In direct parallel with the H1 results discussed above, the chromatin binding region of EBNA can be replaced by those of either H1 or HMG-I, with successful maintenance of daughter cell episomes after cell division [107]. Metaphase chromatin binding is, moreover, a critical aspect of EBNA function [108], as substitute tethers that do not reprise this feature do not secure episome partition to daughter cells [108].

Papilloma viruses also persist as latent circular episomes. In the case of Bovine Papilloma Virus (BPV-1) the operative tether connecting the episome Ori site and chromatin is the viral E2 protein [109]. E2 binds Brd-4, a bromodomain containing protein, and both remain chromatin attached throughout the cell cycle [110]. Human papilloma virus (HPV) E2 proteins also interact with Brd-4, although alternative ligands may be required to secure chromatin attachment of episomes [111]. Thus different DNA virus genera with latent phases utilize similar strategies to ensure episome partitioning to daughter cells.

However, one need not look all the way to DNA viruses to see precedents for the role of LEDGF/p75 in HIV-1 integration. In fact, other retroelements exploit cellular proteins for chromatin attachment in precise ways. For example, retrotransposons in Saccharomyces cervisiae display characteristic integration profiles. Ty1 and Ty3 integrate upstream of RNA pol III promoters, with Ty3 integrating within 1–2 base pairs of transcription start sites [112]. Location specificity is mediated by interactions with the pol III machinery. For Ty3, the Brf and TATA-binding protein (TBP) subunits of TFIIIIB are the major determinants of site choice [112–115].

Ty5 has remarkable integration specificity. In contrast to the relatively restrained (approximately two-fold) targeting effects observed for exogenous retroviruses like HIV-1 and MLV, over 90% of Ty5 retrotransposon insertions occur within quite confined heterochromatic regions at yeast telomeres or at the silent mating loci [116]. This process is mediated by the targeting domain (TD), a six amino acid peptide at the C-terminus of Ty5 integrase, which binds to a heterochromatin-associated protein, Sir4p [117, 118]. Phosphorylation of the TD at a single serine is critical [119]. Mutations that disrupt the TD or prevent phosphorylation of the serine result in randomization of Ty5 integration [119]. Ty5 targeting specificity is re-directed when Sir4p is tethered to ectopic DNA sites or TD is replaced with other peptide motifs that interact with different protein partners [118, 120, 121]. Under conditions of nutrient stress, this process appears to be relaxed by reduction of TD serine phosphorylation, unleashing a potentially adaptive genome-wide insertional mutagenesis [119]. Ty5 IN mimics a cellular protein, Esc-1 which also binds Sir4p. Both proteins contain interchangeable motifs in their C-termini which are required for Sir4p binding [121].

An additional example is the S. pombe LTR retrotransposon Tf1, which integrates preferentially within a window of 100 to 400 nucleotides upstream of open reading frames [122–124]. This targeting is dependent on a chromodomain in the C-terminus of IN [125], and appears to be due to interactions between IN and transcriptional activators for pol II gene promoters [126].

The much greater integration specificity of these retrotransposons in comparison to HIV-1 and MLV is no accident. Unlike the latter exogenous retroviruses, the fate of these genetic parasites is bound to the fate of their host cells, into whose genome they must-integrate. Thus, they have evolved to confine integration into genomic regions where they will not critically disrupt host cell function. The ability of Ty5 to adaptively relax this specificity [119] is all the more remarkable.

A recent report has implicated a retroviral Gag protein as a chromatin attachment factor [127]. Foamy viruses (FV) are complex retroviruses with distinctive life cycle characteristics including completion of reverse transcription in the producer cell and incorporation of the resulting cDNA into the viral particle [128]. The FV Gag protein has a C-terminal group of short basic elements known as Gly-Arg (GR) boxes. One of these, GRI, binds to the viral cDNA. The second, GRII, contains an NLS and a 13 amino acid peptide called the chromatin binding sequence (CBS). The latter binds to chromatin [127], and here the parallel with herpesviruses is clear. Analogous to the equally short KSHV LANA peptide, the CBS peptide interacts with Histone 2A and 2B, although a direct interaction between purified proteins was not yet confirmed. Substitution of the CBS with the first 32 amino acids of KSHV LANA partially trans-complemented a Gag-CBS mutant, tethering some Gag to chromatin. However, functional viral rescue was not observed, possibly because of structural alterations in Gag [127].

Chromatin attachment strategies of DNA viruses and retroelements thus have the common theme that a viral or cellular chromatin binding protein (EBNA/LANA/E2/Sir4p/TFIIIB/LEDGF/p75/Foamy Virus Gag) forms a tether between chromatin and a viral element. The latter can be a DNA episome, e.g. in the case of DNA viruses. For retroelements this can be IN in the case of lentiviruses or yeast retroelements, or the viral cDNA in the case of foamy viruses. Table 1 summarizes viral genera with latent nuclear phases, known chromatin attachment factors and chromatin binding characteristics. LEDGF/p75, like LANA/EBNA and E2 binds mitotic chromatin [37, 39], and like Sir4p and TFIIIB, LEDGF/p75 directly binds viral IN. Figure 3 highlights similarities in tethering mechanisms used by the different viruses discussed.

Table 1.

Summary of viruses with described chromatin attachment proteins

| Virus | Virus family | Chromatin Attachment factor | Chromatin ligand | Viral element tethered | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBV | Herpes | EBNA | AT hooks bind AT rich DNA, EBP2 binding may play role |

Episomal DNA | [105–108] |

| KSHV | Herpes | LANA | Histone 2A/Histone2B | Episomal DNA | [90, 95] |

| BPV | Papilloma | E2 | Brd-4 | Episomal DNA | [110] |

| HPV | Papilloma | E2 | Brd-4 (+/− others) | Episomal DNA | [111] |

| AAV | Parvo | Rep | AAV targeting sequence chromosome 19 | AAV inverted terminal repeat | [147] |

| Ty3 | retrotransposon | TFIIIB | RNA pol III promoters | IN | [113, 114] |

| Ty5 | retrotransposon | Sir4p | Telomeres, Sir4p binds Rap1p | IN | [118, 148] |

| HIV-1 | lentivirus | LEDGF/p75 | AT hooks bind AT rich DNA, PWWP ligand unknown |

IN | [7, 10, 12, 35, 44, 89] |

| FV | Foamy retrovirus | Gag | cDNA | [127] |

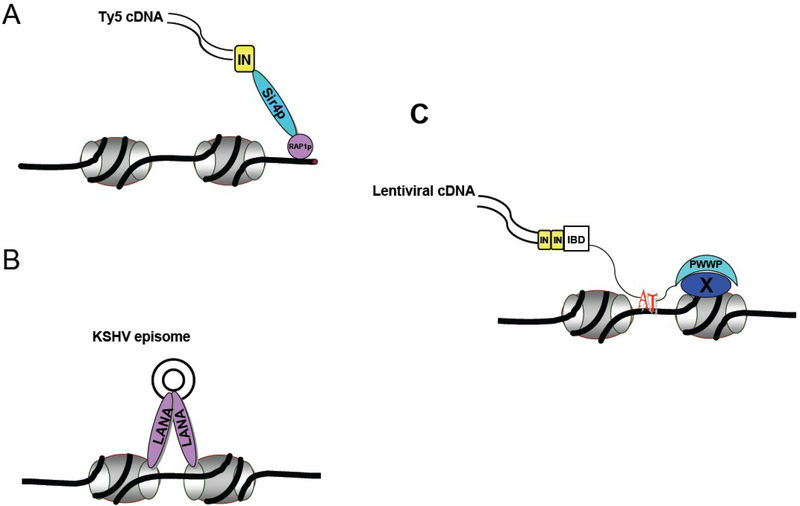

Figure 3: The tether model applies across different classes of viruses.

A) Ty5 retrotransposon utilizes Sir4p to target integration to telomeres and silent mating loci. A specific 6aa targeting domain at the C-terminus of IN binds Sir4p. Sir4p binds Rap1p, a telomeric repeat binding protein, thereby directing the entire complex to telomeres.

B) Latency associated nuclear antigen (LANA) binds to terminal repeats in the DNA of KSHV episome and a groove formed by Histones 2A and 2B, tethering the DNA to chromatin and allowing persistence in latently infected cells.

C) Tethering model for lentiviruses. The cDNA, IN, LEDGF/p75 complex is illustrated. LEDGF/p75 binds an IN dimer. Attachment persists through mitosis. The chromatin ligand of the PWWP domain not known.

Conclusions and Therapeutic Implications

LEDGF/p75-IN binding underlies the integration bias of lentiviruses, namely that of integration into active genes [23, 73, 75, 76]. The fact that substitution of the chromatin binding domain of LEDGF/p75 with alternative chromatin binding motifs yields functional HIV-1 integration cofactor proteins suggests a means to specifically target lentiviral integration. There is an in vitro precedent, in which fusing DNA binding domain of phage lambda repressor to either the IBD or to full length LEDGF/p75 increased integration around the repressor binding sequence [129]. Manipulation of the Ty5/Sir4p interaction has also allowed alteration of Ty5 integration patterns [118]. Fusion of the Ty5 binding domain of Sir4p to Lex A directed integration into the Lex A target site [118]. Substitution of the TD of Ty5 for alternative peptide binding motifs bypassing Sir4p altogether has also allowed site specific integration [118]. This manipulation is possible because the TD of Ty5 is distinct from the CCD, unlike the situation in lentiviruses where the CCD and the LEDGF/p75 binding site overlap.

There is much interest in the possibility of engineering restricted or even site-specific integration of retroviral vectors because of the insertional mutagenesis that recently complicated gammaretroviral vector gene therapy of X linked Severe Combined Immunodeficiency syndrome (SCID-X1) with retroviral vectors encoding the common γ chain [130]. SCID is a rare, profound immune deficiency caused by a number of underlying genetic abnormalities, all of which lead to a block in T cell development with direct or indirect B cell impairment [131]. Children with common gamma chain deficiency have non functional IL-2,4,7,9,15 and 21 receptors, which blocks T and NK cell development and impairs B cell function [131]. The standard treatment is bone marrow transplant. Two gene therapy trials, one in France ( n=10) [132], and one in Britain [133](n=10)were conducted in which CD34+ stem cells were transduced ex vivo with retroviral vectors encoding the common gamma chain,. The gene therapy led to strikingly effective immune reconstitution in 17 of 20 children [132, 134, 135, 136]. However 5 patients developed acute T cell leukemia, and in 4 of them integration of the retroviral vector in the LIM-only 2 (LMO2) oncogene locus was implicated in leukemogenesis [135, 136]. Although one child died from leukemia, the others have responded to chemotherapy and possess persisting immunologically effective transduced T cell populations with continuing clinical benefit [137]. Before these trials began, insertional mutagenesis was considered a fairly low risk for gammaretroviral vector gene therapy [138]. Replication-competent gammaretroviruses were, however, known to readily cause lymphoid malignancies in primates [139]. The new findings from the human trials, along with evidence that retroviruses display specific integration patterns, with MLV preferentially integrating in and around promoters[26, 27], have re-focused the field. In addition, leukemogenesis associated with integration near LMO2 and with aberrant IL2-R gamma chain expression was also reported in mice[140, 141]. Relative targeting of the LMO2 locus, followed by proliferative selection of these rare cells, probably reflects targeting of genes activated during hematopoietic stem cell differentiation[142]. Importantly, the transduced cells had a proliferative advantage in this clinical situation, based on the restitution of multiple cytokine receptors, and the untramelled bone marrow space in which to divide. Thus it appears that transgene, vector and disease-specific aspects contributed to the high incidence of retroviral mutagenesis in these two trials [131]. Nonetheless all avenues to minimize future such events need to be explored. Lentiviruses are attractive for gene therapy for a number of reasons. Lentiviruses in general are not associated directly with carcinogenesis [143, 144] and prefer to target the body of active genes as opposed to promoters, which probably somewhat mitigates the risk of inadvertently activating an oncogene. The basis of their integration site preference is known, and it is possible to manipulate the chromatin targeting domain of LEDGF/p75 and maintain cofactor function [89]. Whether site specific targeting using alternative and more specific chromatin-binding modules will be useful remains to be seen. The ability of a zinc finger DNA binding molecule for example, to bind chromatin tightly might significantly affect its efficacy as an alternate viral tether. There also remains the issue of endogenous LEDGF/p75 in target cells. Only very low fractional levels of this abundant chromatin-attached molecule are required by lentiviruses and eradication of chromatin-bound residua is challenging [71].. Engineered IN-LEDGF/p75 pairs, where reverse charge IN mutants retain catalytic activity, and preferentially interact with reciprocally modified but not wild type LEDGF/p75 have provided one method to circumvent this problem [72]. However, the reverse charge IN vectors displayed decreased viral release and infectivity.

The HIV-1 cofactor activity of LEDGF/p75 is an attractive therapeutic target. The relatively small pocket at the LEDGF/p75-IN interface [12, 70] suggests a small molecule inhbitor is possible[145]. It is also conceivable that a drug that targets the IBD might be useful in the therapy of LEDGF/p75 dependent cancers [48, 146].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Varmus HE, Shank PR, Hughes SE, Kung HJ, Heasley S, Majors J, Vogt PK, Bishop JM, Synthesis, structure, and integration of the DNA of RNA tumor viruses, Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 43 (1979) 851–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Craigie R, HIV integrase, a brief overview from chemistry to therapeutics, J Biol Chem 276 (2001) 23213–23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Poeschla EM, Integrase, LEDGF/p75 and HIV replication, Cell Mol Life Sci February 12; [Epub ahead of print] (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Suzuki Y, Craigie R, The road to chromatin - nuclear entry of retroviruses, Nat Rev Microbiol 5 (2007) 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lin CW, Engelman A, The barrier-to-autointegration factor is a component of functional human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes, J Virol 77 (2003) 5030–5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Farnet CM, Bushman FD, HIV-1 cDNA integration: requirement of HMG I(Y) protein for function of preintegration complexes in vitro, Cell 88 (1997) 483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Llano M, Vanegas M, Fregoso O, Saenz DT, Chung S, Peretz M, Poeschla EM, LEDGF/p75 determines cellular trafficking of diverse lentiviral but not murine oncoretroviral integrase proteins and is a component of functional lentiviral preintegration complexes, J Virol 78 (2004) 9524–9537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Soutoglou E, Misteli T, Mobility and immobility of chromatin in transcription and genome stability, Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 17 (2007) 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Misteli T, Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function, Cell 128 (2007) 787–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cherepanov P, Maertens G, Proost P, Devreese B, Van Beeumen J, Engelborghs Y, De Clercq E, Debyser Z, HIV-1 integrase forms stable tetramers and associates with LEDGF/p75 protein in human cells, J Biol Chem 278 (2003) 372–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ge H, Roeder RG, Purification, cloning, and characterization of a human coactivator, PC4, that mediates transcriptional activation of class II genes, Cell 78 (1994) 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cherepanov P, Ambrosio AL, Rahman S, Ellenberger T, Engelman A, Structural basis for the recognition between HIV-1 integrase and transcriptional coactivator p75, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 (2005) 17308–17313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Busschots K, Vercammen J, Emiliani S, Benarous R, Engelborghs Y, Christ F, Debyser Z, The interaction of LEDGF/p75 with integrase is lentivirus-specific and promotes DNA binding, J Biol Chem 280 (2005) 17841–17847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Esposito D, Craigie R, HIV integrase structure and function, Adv Virus Res 52 (1999) 319–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dyda F, Hickman AB, Jenkins TM, Engelman A, Craigie R, Davies DR, Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases, Science 266 (1994) 1981–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen JC, Krucinski J, Miercke LJ, Finer-Moore JS, Tang AH, Leavitt AD, Stroud RM, Crystal structure of the HIV-1 integrase catalytic core and C-terminal domains: a model for viral DNA binding, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 (2000) 8233–8238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang JY, Ling H, Yang W, Craigie R, Structure of a two-domain fragment of HIV-1 integrase: implications for domain organization in the intact protein, Embo J 20 (2001) 7333–7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rice PA, Baker TA, Comparative architecture of transposase and integrase complexes, Nature Structural Biology 8 (2001) 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bushman FD, Integration site selection by lentiviruses: biology and possible control, Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 261 (2002) 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Muller HP, Varmus HE, DNA bending creates favored sites for retroviral integration: an explanation for preferred insertion sites in nucleosomes, Embo Journal 13 (1994) 4704–4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang GP, Ciuffi A, Leipzig J, Berry CC, Bushman FD, HIV integration site selection: Analysis by massively parallel pyrosequencing reveals association with epigenetic modifications, Genome Res (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hoffmann C, Minkah N, Leipzig J, Wang G, Arens MQ, Tebas P, Bushman FD, DNA bar coding and pyrosequencing to identify rare HIV drug resistance mutations, Nucleic Acids Res (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F, HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots, Cell 110 (2002) 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kang Y, Moressi CJ, Scheetz TE, Xie L, Tran DT, Casavant TL, Ak P, Benham CJ, Davidson BL, McCray PB Jr., Integration site choice of a feline immunodeficiency virus vector, J Virol 80 (2006) 8820–8823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hematti P, Hong BK, Ferguson C, Adler R, Hanawa H, Sellers S, Holt IE, Eckfeldt CE, Sharma Y, Schmidt M, von Kalle C, Persons DA, Billings EM, Verfaillie CM, Nienhuis AW, Wolfsberg TG, Dunbar CE, Calmels B, Distinct genomic integration of MLV and SIV vectors in primate hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, PLoS Biol 2 (2004) e423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wu X, Li Y, Crise B, Burgess SM, Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration, Science 300 (2003) 1749–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mitchell RS, Beitzel BF, Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry CC, Ecker JR, Bushman FD, Retroviral DNA Integration: ASLV, HIV, and MLV Show Distinct Target Site Preferences, PLoS Biol 2 (2004) E234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nowrouzi A, Dittrich M, Klanke C, Heinkelein M, Rammling M, Dandekar T, von Kalle C, Rethwilm A, Genome-wide mapping of foamy virus vector integrations into a human cell line, J Gen Virol 87 (2006) 1339–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Trobridge GD, Miller DG, Jacobs MA, Allen JM, Kiem HP, Kaul R, Russell DW, Foamy virus vector integration sites in normal human cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 (2006) 1498–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lewinski MK, Bisgrove D, Shinn P, Chen H, Hoffmann C, Hannenhalli S, Verdin E, Berry CC, Ecker JR, Bushman FD, Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal features repressing human immunodeficiency virus transcription, J Virol 79 (2005) 6610–6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lewinski MK, Yamashita M, Emerman M, Ciuffi A, Marshall H, Crawford G, Collins F, Shinn P, Leipzig J, Hannenhalli S, Berry CC, Ecker JR, Bushman FD, Retroviral DNA integration: viral and cellular determinants of target-site selection, PLoS Pathog 2 (2006) e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ge H, Si Y, Roeder RG, Isolation of cDNAs encoding novel transcription coactivators p52 and p75 reveals an alternate regulatory mechanism of transcriptional activation, Embo J 17 (1998) 6723–6729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nakamura H, Izumoto Y, Kambe H, Kuroda T, Mori T, Kawamura K, Yamamoto H, Kishimoto T, Molecular cloning of complementary DNA for a novel human hepatoma-derived growth factor. Its homology with high mobility group-1 protein, Journal of Biological Chemistry 269 (1994) 25143–25149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nishizawa Y, Usukura J, Singh DP, Chylack LT Jr., Shinohara T, Spatial and temporal dynamics of two alternatively spliced regulatory factors, lens epithelium-derived growth factor (ledgf/p75) and p52, in the nucleus, Cell Tissue Res 305 (2001) 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Llano M, Vanegas M, Hutchins N, Thompson D, Delgado S, Poeschla EM, Identification and Characterization of the Chromatin Binding Domains of the HIV-1 Integrase Interactor LEDGF/p75, Journal of Molecular Biology 360 (2006) 760–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Turlure F, Maertens G, Rahman S, Cherepanov P, Engelman A, A tripartite DNA-binding element, comprised of the nuclear localization signal and two AT-hook motifs, mediates the association of LEDGF/p75 with chromatin in vivo, Nucleic Acids Res 34 (2006) 1663–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Vanegas M, Llano M, Delgado S, Thompson D, Peretz M, Poeschla E, Identification of the LEDGF/p75 HIV-1 integrase-interaction domain and NLS reveals NLS-independent chromatin tethering, J Cell Sci 118 (2005) 1733–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Maertens G, Cherepanov P, Debyser Z, Engelborghs Y, Engelman A, Identification and characterization of a functional nuclear localization signal in the HIV-1 integrase (IN) interactor LEDGF/p75, J Biol Chem 279 (2004) 33421–33429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Maertens G, Cherepanov P, Pluymers W, Busschots K, De Clercq E, Debyser Z, Engelborghs Y, LEDGF/p75 is essential for nuclear and chromosomal targeting of HIV-1 integrase in human cells, J Biol Chem 278 (2003) 33528–33539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lever MA, Th’ng JP, Sun X, Hendzel MJ, Rapid exchange of histone H1.1 on chromatin in living human cells, Nature 408 (2000) 873–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Th’ng JP, Sung R, Ye M, Hendzel MJ, H1 family histones in the nucleus. Control of binding and localization by the C-terminal domain, J Biol Chem 280 (2005) 27809–27814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen D, Dundr M, Wang C, Leung A, Lamond A, Misteli T, Huang S, Condensed mitotic chromatin is accessible to transcription factors and chromatin structural proteins, Journal of Cell Biology 168 (2005) 41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Phair RD, Scaffidi P, Elbi C, Vecerova J, Dey A, Ozato K, Brown DT, Hager G, Bustin M, Misteli T, Global nature of dynamic protein-chromatin interactions in vivo: three-dimensional genome scanning and dynamic interaction networks of chromatin proteins, Mol Cell Biol 24 (2004) 6393–6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cherepanov P, Devroe E, Silver PA, Engelman A, Identification of an evolutionarily conserved domain in human lens epithelium-derived growth factor/transcriptional co-activator p75 (LEDGF/p75) that binds HIV-1 integrase, J Biol Chem 279 (2004) 48883–48892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bartholomeeusen K, Christ F, Hendrix J, Rain JC, Emiliani S, Benarous R, Debyser Z, Gijsbers R, De Rijck J, Lens epithelium-derived growth factor/p75 interacts with the transposase-derived DDE domain of PogZ, Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (2009) 11467–11477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Maertens GN, Cherepanov P, Engelman A, Transcriptional co-activator p75 binds and tethers the Myc-interacting protein JPO2 to chromatin, J Cell Sci 119 (2006) 2563–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bartholomeeusen K, De Rijck J, Busschots K, Desender L, Gijsbers R, Emiliani S, Benarous R, Debyser Z, Christ F, Differential Interaction of HIV-1 Integrase and JPO2 with the C Terminus of LEDGF/p75, J Mol Biol 372 (2007) 407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yokoyama A, Cleary ML, Menin critically links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes.[see comment], Cancer Cell 14 (2008) 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Singh DP, Ohguro N, Kikuchi T, Sueno T, Reddy VN, Yuge K, Chylack LT Jr., Shinohara T, Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: effects on growth and survival of lens epithelial cells, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 267 (2000) 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Inomata Y, Hirata A, Koga T, Kimura A, Singh DP, Shinohara T, Tanihara H, Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: neuroprotection on rat retinal damage induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate, Brain Res 991 (2003) 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sharma P, Singh DP, Fatma N, Chylack LT Jr., Shinohara T, Activation of LEDGF gene by thermal-and oxidative-stresses, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 276 (2000) 1320–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Matsui H, Lin LR, Singh DP, Shinohara T, Reddy VN, Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: increased survival and decreased DNA breakage of human RPE cells induced by oxidative stress, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42 (2001) 2935–2941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Singh DP, Ohguro N, Chylack LT Jr., Shinohara T, Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: increased resistance to thermal and oxidative stresses, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40 (1999) 1444–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nakamura M, Singh DP, Kubo E, Chylack LT Jr., Shinohara T, LEDGF: survival of embryonic chick retinal photoreceptor cells, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41 (2000) 1168–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Machida S, Chaudhry P, Shinohara T, Singh DP, Reddy VN, Chylack LT Jr., Sieving PA, Bush RA, Lens epithelium-derived growth factor promotes photoreceptor survival in light-damaged and RCS rats, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42 (2001) 1087–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sutherland HG, Newton K, Brownstein DG, Holmes MC, Kress C, Semple CA, Bickmore WA, Disruption of Ledgf/Psip1 results in perinatal mortality and homeotic skeletal transformations, Mol Cell Biol 26 (2006) 7201–7210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Caslini C, Yang Z, El-Osta M, Milne TA, Slany RK, Hess JL, Interaction of MLL amino terminal sequences with menin is required for transformation, Cancer Research 67 (2007) 7275–7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hess JL, Mechanisms of transformation by MLL, Critical Reviews in Eukaryotic Gene Expression 14 (2004) 235–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Scacheri PC, Davis S, Odom DT, Crawford GE, Perkins S, Halawi MJ, Agarwal SK, Marx SJ, Spiegel AM, Meltzer PS, Collins FS, Genome-wide analysis of menin binding provides insights into MEN1 tumorigenesis, PLoS Genetics 2 (2006) e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Yokoyama A, Somervaille TC, Smith KS, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Meyerson M, Cleary ML, The menin tumor suppressor protein is an essential oncogenic cofactor for MLL-associated leukemogenesis, Cell 123 (2005) 207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Roudaia L, Speck NA, A MENage a Trois in leukemia.[comment], Cancer Cell 14 (2008) 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Llano M, Delgado S, Vanegas M, Poeschla EM, LEDGF/p75 prevents proteasomal degradation of HIV-1 integrase, J Biol Chem 279 (2004) 55570–55577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Cherepanov P, LEDGF/p75 interacts with divergent lentiviral integrases and modulates their enzymatic activity in vitro, Nucleic Acids Res 35 (2007) 113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Engelman A, Cherepanov P, The lentiviral integrase binding protein LEDGF/p75 and HIV-1 replication, PLoS Pathogens 4 (2008) e1000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Busschots K, Voet A, De Maeyer M, Rain JC, Emiliani S, Benarous R, Desender L, Debyser Z, Christ F, Identification of the LEDGF/p75 binding site in HIV-1 integrase, J Mol Biol 365 (2007) 1480–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bouyac-Bertoia M, Dvorin J, Fouchier R, Jenkins Y, Meyer B, Wu L, Emerman M, Malim MH, HIV-1 infection requires a functional integrase NLS, Molecular Cell 7 (2001) 1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Dvorin JD, Bell P, Maul GG, Yamashita M, Emerman M, Malim MH, Reassessment of the roles of integrase and the central DNA flap in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nuclear import, J Virol 76 (2002) 12087–12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Limon A, Devroe E, Lu R, Ghory HZ, Silver PA, Engelman A, Nuclear Localization of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Preintegration Complexes (PICs): V165A and R166A Are Pleiotropic Integrase Mutants Primarily Defective for Integration, Not PIC Nuclear Import, J Virol 76 (2002) 10598–10607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Turlure F, Devroe E, Silver PA, Engelman A, Human cell proteins and human immunodeficiency virus DNA integration, Front Biosci 9 (2004) 3187–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cherepanov P, Sun ZY, Rahman S, Maertens G, Wagner G, Engelman A, Solution structure of the HIV-1 integrase-binding domain in LEDGF/p75, Nat Struct Mol Biol 12 (2005) 526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Llano M, Saenz DT, Meehan A, Wongthida P, Peretz M, Walker WH, Teo W, Poeschla EM, An Essential Role for LEDGF/p75 in HIV Integration, Science 314 (2006) 461–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Hare S, Shun MC, Gupta SS, Valkov E, Engelman A, Cherepanov P, A novel co-crystal structure affords the design of gain-of-function lentiviral integrase mutants in the presence of modified PSIP1/LEDGF/p75, PLoS Pathogens 5 (2009) e1000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Shun MC, Raghavendra NK, Vandegraaff N, Daigle JE, Hughes S, Kellam P, Cherepanov P, Engelman A, LEDGF/p75 functions downstream from preintegration complex formation to effect gene-specific HIV-1 integration, Genes Dev 21 (2007) 1767–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Vandekerckhove L, Christ F, Van Maele B, De Rijck J, Gijsbers R, Van den Haute C, Witvrouw M, Debyser Z, Transient and stable knockdown of the integrase cofactor LEDGF/p75 reveals its role in the replication cycle of human immunodeficiency virus, J Virol 80 (2006) 1886–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Marshall HM, Ronen K, Berry C, Llano M, Sutherland H, Saenz D, Bickmore W, Poeschla E, Bushman FD, Role of PSIP1/LEDGF/p75 in Lentiviral Infectivity and Integration Targeting, PLoS ONE 2 (2007) e1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Ciuffi A, Llano M, Poeschla E, Hoffmann C, Leipzig J, Shinn P, Ecker JR, Bushman F, A role for LEDGF/p75 in targeting HIV DNA integration, Nature Medicine 11 (2005) 1287–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].De Rijck J, Vandekerckhove L, Gijsbers R, Hombrouck A, Hendrix J, Vercammen J, Engelborghs Y, Christ F, Debyser Z, Overexpression of the lens epithelium-derived growth factor/p75 integrase binding domain inhibits human immunodeficiency virus replication, J Virol 80 (2006) 11498–11509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Hombrouck A, De Rijck J, Hendrix J, Vandekerckhove L, Voet A, Maeyer MD, Witvrouw M, Engelborghs Y, Christ F, Gijsbers R, Debyser Z, Virus Evolution Reveals an Exclusive Role for LEDGF/p75 in Chromosomal Tethering of HIV, PLoS Pathog 3 (2007) e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Yu F, Jones GS, Hung M, Wagner AH, MacArthur HL, Liu X, Leavitt S, McDermott MJ, Tsiang M, HIV-1 integrase preassembled on donor DNA is refractory to activity stimulation by LEDGF/p75, Biochemistry 46 (2007) 2899–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Hayouka Z, Rosenbluh J, Levin A, Loya S, Lebendiker M, Veprintsev D, Kotler M, Hizi A, Loyter A, Friedler A, Inhibiting HIV-1 integrase by shifting its oligomerization equilibrium, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 (2007) 8316–8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].McKee CJ, Kessl JJ, Shkriabai N, Dar MJ, Engelman A, Kvaratskhelia M, Dynamic modulation of HIV-1 integrase structure and function by cellular lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF) protein, Journal of Biological Chemistry 283 (2008) 31802–31812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Pandey KK, Sinha S, Grandgenett DP, Transcriptional Coactivator LEDGF/p75 Modulates Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrase-Mediated Concerted Integration, J Virol 81 (2007) 3969–3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Faure A, Calmels C, Desjobert C, Castroviejo M, Caumont-Sarcos A, Tarrago-Litvak L, Litvak S, Parissi V, HIV-1 integrase crosslinked oligomers are active in vitro, Nucleic Acids Res 33 (2005) 977–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Guiot E, Carayon K, Delelis O, Simon F, Tauc P, Zubin E, Gottikh M, Mouscadet JF, Brochon JC, Deprez E, Relationship between the oligomeric status of HIV-1 integrase on DNA and enzymatic activity, J Biol Chem 281 (2006) 22707–22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Li M, Mizuuchi M, Burke TR Jr., Craigie R, Retroviral DNA integration: reaction pathway and critical intermediates, Embo J 25 (2006) 1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Crise B, Li Y, Yuan C, Morcock DR, Whitby D, Munroe DJ, Arthur LO, Wu X, Simian immunodeficiency virus integration preference is similar to that of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, J Virol 79 (2005) 12199–12204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].MacNeil A, Sankale JL, Meloni ST, Sarr AD, Mboup S, Kanki P, Genomic sites of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) integration: similarities to HIV-1 in vitro and possible differences in vivo, J Virol 80 (2006) 7316–7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Hacker CV, Vink CA, Wardell TW, Lee S, Treasure P, Kingsman SM, Mitrophanous KA, Miskin JE, The integration profile of EIAV-based vectors, Mol Ther 14 (2006) 536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Meehan Anne M, Morrison James H, Garcia-Rivera Jose A,Llano M, Mary Peretz, Poeschla Eric M. LEDGF/p75 Proteins with Alternative Chromatin Tethers are Functional HIV-1 Cofactors, PLoS Pathogens (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Barbera AJ, Chodaparambil JV, Kelley-Clarke B, Joukov V, Walter JC, Luger K, Kaye KM, The nucleosomal surface as a docking station for Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus LANA, Science 311 (2006) 856–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Bednar J, Horowitz RA, Grigoryev SA, Carruthers LM, Hansen JC, Koster AJ, Woodcock CL, Nucleosomes, linker DNA, and linker histone form a unique structural motif that directs the higher-order folding and compaction of chromatin, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 (1998) 14173–14178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Harvey AC, Downs JA, What functions do linker histones provide?, Mol Microbiol 53 (2004) 771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Hendzel MJ, Lever MA, Crawford E, Th’ng JP, The C-terminal domain is the primary determinant of histone H1 binding to chromatin in vivo, J Biol Chem 279 (2004) 20028–20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Catez F, Ueda T, Bustin M, Determinants of histone H1 mobility and chromatin binding in living cells, Nat Struct Mol Biol 13 (2006) 305–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Barbera AJ, Chodaparambil JV, Kelley-Clarke B, Luger K, Kaye KM, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA hitches a ride on the chromosome, Cell Cycle 5 (2006) 1048–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Verma SC, Robertson ES, Molecular biology and pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, FEMS Microbiology Letters 222 (2003) 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Shinohara H, Fukushi M, Higuchi M, Oie M, Hoshi O, Ushiki T, Hayashi J, Fujii M, Chromosome binding site of latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is essential for persistent episome maintenance and is functionally replaced by histone H1, Journal of Virology 76 (2002) 12917–12924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Roe T, Reynolds TC, Yu G, Brown PO, Integration of murine leukemia virus DNA depends on mitosis, Embo J 12 (1993) 2099–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Lewis PF, Emerman M, Passage through mitosis is required for oncoretroviruses but not for the human immunodeficiency virus, Journal of Virology 68 (1994) 510–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Swanson JA, McNeil PL, Nuclear reassembly excludes large macromolecules, Science 238 (1987) 548–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Benavente R, Scheer U, Chaly N, Nucleocytoplasmic sorting of macromolecules following mitosis: fate of nuclear constituents after inhibition of pore complex function, European Journal of Cell Biology 50 (1989) 209–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Brown PO, Integration, in: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE (Eds.), Retroviruses, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y., 1999, pp. 161–203. [Google Scholar]

- [103].Ludtke JJ, Sebestyen MG, Wolff JA, The effect of cell division on the cellular dynamics of microinjected DNA and dextran.[erratum appears in Mol Ther. 2002 Jul;6(1):134.], Molecular Therapy: the Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 5 (2002) 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Ciuffi A, Bushman FD, Retroviral DNA integration: HIV and the role of LEDGF/p75, Trends Genet 22 (2006) 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Sears J, Ujihara M, Wong S, Ott C, Middeldorp J, Aiyar A, The amino terminus of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 1 contains AT hooks that facilitate the replication and partitioning of latent EBV genomes by tethering them to cellular chromosomes, J Virol 78 (2004) 11487–11505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Wu H, Ceccarelli DF, Frappier L, The DNA segregation mechanism of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1, EMBO Reports 1 (2000) 140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Hung SC, Kang MS, Kieff E, Maintenance of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) oriP-based episomes requires EBV-encoded nuclear antigen-1 chromosome-binding domains, which can be replaced by high-mobility group-I or histone H1, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 (2001) 1865–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Sears J, Kolman J, Wahl GM, Aiyar A, Metaphase chromosome tethering is necessary for the DNA synthesis and maintenance of oriP plasmids but is insufficient for transcription activation by Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1, J Virol 77 (2003) 11767–11780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Ilves I, Kivi S, Ustav M, Long-term episomal maintenance of bovine papillomavirus type 1 plasmids is determined by attachment to host chromosomes, which Is mediated by the viral E2 protein and its binding sites, Journal of Virology 73 (1999) 4404–4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].You J, Croyle JL, Nishimura A, Ozato K, Howley PM, Interaction of the bovine papillomavirus E2 protein with Brd4 tethers the viral DNA to host mitotic chromosomes.[see comment], Cell 117 (2004) 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Oliveira JG, Colf LA, McBride AA, Variations in the association of papillomavirus E2 proteins with mitotic chromosomes, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (2006) 1047–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Kirchner J, Connolly CM, Sandmeyer SB, Requirement of RNA polymerase III transcription factors for in vitro position-specific integration of a retroviruslike element, Science 267 (1995) 1488–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Aye M, Irwin B, Beliakova-Bethell N, Chen E, Garrus J, Sandmeyer S, Host factors that affect Ty3 retrotransposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics 168 (2004) 1159–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Chalker DL, Sandmeyer SB, Ty3 integrates within the region of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation, Genes & Development 6 (1992) 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Yieh L, Kassavetis G, Geiduschek EP, Sandmeyer SB, The Brf and TATA-binding protein subunits of the RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB mediate position-specific integration of the gypsy-like element, Ty3, Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (2000) 29800–29807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Zou S, Ke N, Kim JM, Voytas DF, The Saccharomyces retrotransposon Ty5 integrates preferentially into regions of silent chromatin at the telomeres and mating loci, Genes Dev 10 (1996) 634–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Xie W, Gai X, Zhu Y, Zappulla DC, Sternglanz R, Voytas DF, Targeting of the yeast Ty5 retrotransposon to silent chromatin is mediated by interactions between integrase and Sir4p, Mol Cell Biol 21 (2001) 6606–6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Zhu Y, Dai J, Fuerst PG, Voytas DF, Controlling integration specificity of a yeast retrotransposon, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 (2003) 5891–5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Dai J, Xie W, Brady TL, Gao J, Voytas DF, Phosphorylation regulates integration of the yeast Ty5 retrotransposon into heterochromatin, Mol Cell 27 (2007) 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Sandmeyer S, Integration by design, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 (2003) 5586–5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Brady TL, Fuerst PG, Dick RA, Schmidt C, Voytas DF, Retrotransposon target site selection by imitation of a cellular protein, Molecular & Cellular Biology 28 (2008) 1230–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Bowen NJ, Jordan IK, Epstein JA, Wood V, Levin HL, Retrotransposons and their recognition of pol II promoters: a comprehensive survey of the transposable elements from the complete genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Genome Research 13 (2003) 1984–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Singleton TL, Levin HL, A long terminal repeat retrotransposon of fission yeast has strong preferences for specific sites of insertion, Eukaryotic Cell 1 (2002) 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Behrens R, Hayles J, Nurse P, Fission yeast retrotransposon Tf1 integration is targeted to 5’ ends of open reading frames, Nucleic Acids Research 28 (2000) 4709–4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Chatterjee AG, Leem YE, Kelly FD, Levin HL, The chromodomain of Tf1 integrase promotes binding to cDNA and mediates target site selection, Journal of Virology 83 (2009) 2675–2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Leem YE, Ripmaster TL, Kelly FD, Ebina H, Heincelman ME, Zhang K, Grewal SI, Hoffman CS, Levin HL, Retrotransposon Tf1 is targeted to Pol II promoters by transcription activators, Molecular Cell 30 (2008) 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Tobaly-Tapiero J, Bittoun P, Lehmann-Che J, Delelis O, Giron ML, de The H, Saib A, Chromatin tethering of incoming foamy virus by the structural Gag protein, Traffic 9 (2008) 1717–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Moebes A, Enssle J, Bieniasz PD, Heinkelein M, Lindemann D, Bock M, McClure MO, Rethwilm A, Human foamy virus reverse transcription that occurs late in the viral replication cycle, Journal of Virology 71 (1997) 7305–7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Ciuffi A, Diamond TL, Hwang Y, Marshall HM, Bushman FD, Modulating target site selection during human immunodeficiency virus DNA integration in vitro with an engineered tethering factor, Hum Gene Ther 17 (2006) 960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, Lim A, Osborne CS, Pawliuk R, Morillon E, Sorensen R, Forster A, Fraser P, Cohen JI, de Saint Basile G, Alexander I, Wintergerst U, Frebourg T, Aurias A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Romana S, Radford-Weiss I, Gross F, Valensi F, Delabesse E, Macintyre E, Sigaux F, Soulier J, Leiva LE, Wissler M, Prinz C, Rabbitts TH, Le Deist F, Fischer A, Cavazzana-Calvo M, LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1, Science 302 (2003) 415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Cavazzana-Calvo M, Fischer A, Gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency: are we there yet?, J Clin Invest 117 (2007) 1456–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, de Saint Basile G, Gross F, Yvon E, Nusbaum P, Selz F, Hue C, Certain S, Casanova JL, Bousso P, Deist FL, Fischer A, Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease, Science 288 (2000) 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Gaspar HB, Parsley KL, Howe S, King D, Gilmour KC, Sinclair J, Brouns G, Schmidt M, Von Kalle C, Barington T, Jakobsen MA, Christensen HO, Al Ghonaium A, White HN, Smith JL, Levinsky RJ, Ali RR, Kinnon C, Thrasher AJ, Gene therapy of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by use of a pseudotyped gammaretroviral vector, Lancet 364 (2004) 2181–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Fischer A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Gene therapy for immunodeficiency diseases, Seminars in Hematology 41 (2004) 272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, Soulier J, Lim A, Morillon E, Clappier E, Caccavelli L, Delabesse E, Beldjord K, Asnafi V, MacIntyre E, Dal Cortivo L, Radford I, Brousse N, Sigaux F, Moshous D, Hauer J, Borkhardt A, Belohradsky BH, Wintergerst U, Velez MC, Leiva L, Sorensen R, Wulffraat N, Blanche S, Bushman FD, Fischer A, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1, Journal of Clinical Investigation 118 (2008) 3132–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Howe SJ, Mansour MR, Schwarzwaelder K, Bartholomae C, Hubank M, Kempski H, Brugman MH, Pike-Overzet K, Chatters SJ, de Ridder D, Gilmour KC, Adams S, Thornhill SI, Parsley KL, Staal FJ, Gale RE, Linch DC, Bayford J, Brown L, Quaye M, Kinnon C, Ancliff P, Webb DK, Schmidt M, von Kalle C, Gaspar HB, Thrasher AJ, Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients, Journal of Clinical Investigation 118 (2008) 3143–3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Pike-Overzet K, van der Burg M, Wagemaker G, van Dongen JJ, Staal FJ, New Insights and Unresolved Issues Regarding Insertional Mutagenesis in X-linked SCID Gene Therapy, Mol Ther 15 (2007) 1910–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Cornetta K, Morgan RA, Anderson WF, Safety issues related to retroviral-mediated gene transfer in humans, Human Gene Therapy 2 (1991) 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Donahue RE, Kessler SW, Bodine D, McDonagh K, Dunbar C, Goodman S, Agricola B, Byrne E, Raffeld M, Moen R, et al. , Helper virus induced T cell lymphoma in nonhuman primates after retroviral mediated gene transfer, J Exp Med 176 (1992) 1125–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Dave UP, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Gene therapy insertional mutagenesis insights, Science 303 (2004) 333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Li Z, Dullmann J, Schiedlmeier B, Schmidt M, von Kalle C, Meyer J, Forster M, Stocking C, Wahlers A, Frank O, Ostertag W, Kuhlcke K, Eckert HG, Fehse B, Baum C, Murine leukemia induced by retroviral gene marking, Science 296 (2002) 497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].McCormack MP, Rabbitts TH, Activation of the T-cell oncogene LMO2 after gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency.[see comment], New England Journal of Medicine 350 (2004) 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Modlich U, Baum C, Preventing and exploiting the oncogenic potential of integrating gene vectors.[comment], Journal of Clinical Investigation 119 (2009) 755–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Montini E, Cesana D, Schmidt M, Sanvito F, Bartholomae CC, Ranzani M, Benedicenti F, Sergi LS, Ambrosi A, Ponzoni M, Doglioni C, Di Serio C, von Kalle C, Naldini L, The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy.[see comment], Journal of Clinical Investigation 119 (2009) 964–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]