Highlights

-

•

We tested the cross-domain effects of personal resources/demands on employees’ work engagement (WE).

-

•

We studied Chinese employees from a range of different service settings using a daily diary design.

-

•

Employees’ WE was rated by their manager.

-

•

Personal resources at home contributed to WE by increasing/decreasing personal resources/demands at work.

-

•

Personal demands at home jeopardized WE by decreasing/increasing personal resources/demands at work.

Keywords: Personal resources, Personal demands, Work engagement, Conservation of resources theory, Work-home interface, Chinese

Abstract

Conventional studies have widely demonstrated that individuals’ engagement at work depends on their personal resources, which are affected by environmental influences, especially those derived from the workplace and home domains. In this study, we examine whether a change in work engagement may be based on individuals’ decisions in managing their personal resources. We use the conservation of resources (COR) theory to explain how personal resources and personal demands at home can influence work engagement through personal resources and personal demands at work. We conducted a daily diary study involving a group of 97 Chinese employees (N = 97) from a range of different service settings for 2 consecutive weeks (N = 1358) and evaluated their daily work engagement using manager ratings. The findings support the hypothesized mediating effects of personal resources and personal demands at work on personal resources and personal demands at home and work engagement.

1. Introduction

The recent catastrophic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the hospitality industry has provided a highly visible reminder on how important this sector is for the economies of many countries. As one of the most affected economic sectors (Nicola et al., 2020), the hospitality industry suffered high levels of business failures and layoffs of both core and casual employees. Recovering from this impact in difficult and likely volatile trading circumstances, and regaining and sustaining high levels of service quality will require significant employee responsiveness and engagement. While much recent research has investigated ways in which work engagement of service employees in general and hospitality employees in particular can be improved (e.g., Ali et al., 2016; Karatepe, 2013; Karatepe and Demir, 2014; Lee, 2015; Paek et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2018), the experiences of many different employers and employees during the Covid-19 pandemic have only highlighted how close the connections are between the home lives of employees and their engagement with and performance at work.

Generally, behavioral investigations of work engagement assume that individuals engage in work not only because the work is enjoyable to them but also because they can acquire an improved sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, and personal pride during this engagement, which eventually motivate them to perform better at work (Schaufeli et al., 2002). However, by voluntarily investing ongoing effort in work and solving job challenges, individuals expend physical energy and deplete other available resources, such as time (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Individuals may acquire new personal resources and may deplete their existing personal resources during this engagement. Work engagement therefore both generates and taxes personal resources.

Studies on work engagement have widely involved cross-domain issues and have discussed how non-work domains, such as home, impact work engagement (e.g., ten Brummelhuis et al., 2011; Hakanen et al., 2008; Rothbard, 2001). For instance, individuals may use energy at home that they could have used at work, which leaves them insufficient energy available to stay engaged at work (family-to-work conflict perspective, see Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). They may also acquire knowledge or emotional support at home that contributes to improving their job performance, thereby motivating them to stay engaged at work (family-to-work enrichment perspective, see Greenhaus and Powell, 2006). Work engagement may change over time, and studies on related issues have revealed supportive findings by measuring it on a daily/weekly basis (e.g., Bakker and Demerouti, 2009). However, many recent studies in the hospitality management field on work engagement issues have largely conceptualized work engagement as stable over time (e.g., Cheng and Chen, 2017; Guan et al., 2020; Putra et al., 2017; Tsaur et al., 2019), which may not precisely reflect employees’ work engagement. Our study addresses this gap in the hospitality management literature by conceptualizing work engagement as a work state that fluctuates over time.

The question of whether a change in work engagement may be based on an individual’s management of personal resources and personal demands has been neglected in the literature. Many theories, such as conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018), reveal that individuals naturally manipulate available resources across domains on a daily basis in addition to being impacted by the domains in which they operate. This is particularly salient in service settings such as hospitality where factors such as unsociable hours, work intensity, narrowing borders between work and non-work domains, and the emotional demands of service encounters negatively affect employees’ work-life balance (Kaya and Karatepe, 2020a). COR theory has been widely emphasized in contemporary studies and adopted as the theoretical underpinning for the development of other theories, such as the work-home resources model (e.g., ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012a). In light of the above, it is valuable and important to study how employees in service settings like hospitality manage these resources and demands across domains (e.g., home to work) and how this management impacts their subsequent behaviors (e.g., work engagement) to comprehensively understand the role of personal resources in their behaviors from a cross-domain perspective and to address the knowledge gap in the literature.

To answer the aforementioned research question, we aim to investigate whether daily personal resources and daily personal demands at home affect daily work engagement through daily personal resources and daily personal demands at work. The choice of the home domain is particularly appropriate since substantial research findings indicate that family issues are one of the most problematic issues across companies globally (e.g., Li et al., 2015). Moreover, the home environment plays an important role in the daily recovery of employees from work demands (Sonnentag, 2003; Sonnentag et al., 2017), but it can also be a daily source of pressures that can affect employees at work (Demerouti et al., 2010; Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). Therefore, it is conceivable that personal demands and personal resources at the home and work domains may fluctuate on a daily basis and that these demands and resources may have an impact on employees’ daily work engagement. However, many recent studies in the hospitality management field on work and home issues have largely conceptualized the influences derived from these domains as stable (e.g., Gamor et al., 2018; García-Cabrera et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2016; O’Neill and Follmer, 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020). Our study addresses this by conceptualizing those influences as variable in nature.

Our sample comprised a group of Chinese employees. China is characterized by a strong family culture that leads family influences to play a significant role in Chinese employees’ work life (Lee and Knobf, 2016) and makes the domains of family and work closely interconnected (Du et al., 2018). Understanding whether and how these influences predict work engagement is particularly important for service organizations given the emotional labor (Grandey, 2000; Park et al., 2019) involved in service encounters, which can be particularly taxing in hospitality settings due to the nature and frequency of direct customer interactions (Pizam, 2004). Such emotional labor requires sufficient personal resources for employees to achieve and maintain high levels of service quality (Jung and Yoon, 2014; Lee and Ok, 2012; Park et al., 2019). However, while recent studies in service settings heavily investigated the role of job influences in work engagement (e.g., Chen, 2019; Gürlek and Tuna, 2019; Kaya and Karatepe, 2020b; Olugbade and Karatepe, 2019; Park et al., 2019; Tsaur et al., 2019), relatively less attention has been paid to the role of the influences derived from non-work domains on work engagement. This limits the development of pragmatic implications for improving work engagement in the hospitality industry. Our study thus investigates factors of significant theoretical and pragmatic interest.

We refer to the home domain rather than the family domain because the former incorporates a wider range of aspects of individuals’ living arrangements, including family (Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012a). To achieve our aim, we define personal resources (Lin, 1982, 2017) as tangible, social, psychological or symbolic assets that are valued by a person and that are directly available to improve effective functioning in specific domains. This definition is in line with COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018) as well as with other commonly used resource approaches (see Grawitch et al., 2010; Hobfoll, 2002; ten Brummelhuis et al., 2012) in that it views all resources, including those originating in the work or home setting, as personal resources that are at the disposal of the individual. Adopting this particular definition helps explicitly articulate how individuals manage their personal resources across domains.

There is no recognized definition of personal demands in the literature. Abundant research findings show the existence of aspects derived from individuals’ environments and within-person aspects that contradict personal resources and must be addressed (e.g., work pressure and childcare; Li et al., 2015). Thus, we conceptualize these demands as personal demands and define them as tangible, social, psychological or symbolic factors that attract individual attention and that require physical, cognitive or emotional effort to prevent them from interfering with valued activities or with the personal resources required to pursue such activities. Such personal demands may stem from internal sources or from a particular domain in which an individual operates.

This definition is in line with the logic of resource-based theories such as COR theory (Hobfoll, 2002; Hobfoll et al., 2018) and other resource approaches (e.g., Grawitch et al., 2010) and views all factors that threaten, deplete or obliterate valued personal resources as personal demands. In this context, job and home demands are included in the personal demands that individuals experience and strive to diminish. Typically, demands and resources arising in a particular domain most obviously affect each other in that setting. However, a premise of this research is that in line with the perspective of family-to-work enrichment/conflict (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985; Greenhaus and Powell, 2006), work-family facilitation theory (e.g., Wayne et al., 2007), spillover theory (e.g., Hanson et al., 2006), and relevant empirical evidence (e.g., Demerouti et al., 2016; Du et al., 2018; Rothbard, 2001; ten Brummelhuis et al., 2012), personal demands/resources in one domain can affect those in another domain.

In alignment with these perspectives, we propose that personal resources at home may alleviate personal demands and may help maintain personal resources available at work. This may motivate individuals to engage in work because they may have abundant personal resources available at work to invest in such engagement and may be more inclined to acquire additional resources by engaging in work. We also propose that personal demands at home may deplete personal resources and may exacerbate demands at work. This may result in individuals engaging less in work because they may enter a defensive mode to preserve their remaining personal resources at work or experience a stalemate of resource investment, which may lead them to reduce or stop investing these resources in work engagement. Hence, our research has important theoretical implications. Conventional studies and theories, such as the job demands-resources model, posit that individuals become less engaged due to the exhaustion of available personal resources at work and that they become more engaged due to an improved sense of ability to perform effectively at work (e.g., Breevaart et al., 2019; Conway et al., 2016; Demerouti et al., 2016; Ott et al., 2019). Our study holds that becoming less engaged may result from efforts to preserve resources at work in the presence of home demands, and that engagement may be a result from an innate tendency to acquire additional resources during engagement.

This theoretical distinction between conventional claims arising from the environment-centered and domain-specific perspective of prior work and the claims derived from the individual-centered perspective reflected in our focus on personal resources differentiates this study from extant research. This study adds novel insights to the literature by proposing that individuals may not always be passive responders to resources and demands arising in particular domains they operate, but instead may take a more active role in managing their personal resources across domains (e.g., by entering a defensive mode to preserve their remaining personal resources). Reduced work engagement may hence be a more proactive response to facing reduced personal resources and/or increased personal demands at work and not simply an automatic reactive response to the depletion of personal resources at work.

We thus contribute to the literature in three ways. First, by adopting COR theory, we provide theoretical insights into the dynamics of work engagement from a cross-domain perspective, which contributes to the work engagement and work-family interface literature. Second, our investigation involves the positive and negative interference of home with work (i.e., home-to-work enrichment and conflict). Using COR theory, we primarily focus on the person rather than the environment to investigate enrichment processes across domains. We also explicitly demonstrate a conflicting causal process that links the home and work domains to address a theoretical limitation of work-family conflict that has been criticized in existing studies (Grandey and Cropanzano, 1999). Third, we extend COR theory by proposing the role of personal demands from the perspectives of resource gain and loss spirals and by using manager-rated work engagement to provide empirical evidence to support the role of personal resources in the theory.

2. Personal resources/demands, home-to-work enrichment/conflict, and engagement

In this study, rather than adopting theories of work-family conflict and enrichment, we use COR theory to articulate the hypotheses for the following reasons. The theory of work-family conflict has been criticized for not explicitly demonstrating a conflicting causal process that links the home and work domains (e.g., family-to-work conflict; Grandey and Cropanzano, 1999). The theory of work-family enrichment proposes that family-to-work enrichment may occur when resources derived from the family contribute to performance at work (Greenhaus and Powell, 2006). However, an explicit demonstration of employees’ behavior regarding how they use these resources at work has not been sufficiently articulated. The use of COR theory helps us address and further contribute to these specific theoretical limitations by focusing on individuals and their resources rather than the environmental aspects of resources and factors that can deplete them (i.e., demands).

The heart of COR theory is the notion that individuals have a natural tendency to protect, maintain, foster and further acquire resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Resources refer to anything that is valued by individuals to improve their effective functioning and support their performance (Halbesleben et al., 2014), which is in line with our conceptualization of personal resources. Empirical studies have revealed that personal resources, such as job/home resources, are used by individuals to eliminate demands and to support their performance in their respective domains (e.g., Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012a). The scope of these resources may include objects (e.g., a mobile phone), states (e.g., confidence), conditions (e.g., winning a competition), and others (e.g., time, energy, social status).

According to COR theory, individuals invest resources to protect themselves against or recover from resource loss and to acquire resources. When they acquire resources, they are better positioned to invest and obtain additional resources (a resource gain spiral) and are more inclined to invest their available resources for additional resource gain. However, when they lose resources, any investment for additional resources is more difficult as they become more vulnerable to resource loss (a resource loss spiral). In addition, individuals are biased to be more sensitive to resource losses and less sensitive to resource gains (Hobfoll et al., 2018). This leads individuals to become more defensive in the way they invest their remaining resources. Empirical studies have found that individuals who experience resource loss take action to protect their remaining resources (e.g., Halbesleben and Bowler, 2007). One aspect of the theory that has not been frequently mentioned in the literature is the stalemate of resource investment (Halbesleben et al., 2014). COR theory specifies that at some point in resource investment, individuals may perceive that their endeavor has come to a stalemate; for example, they may find it difficult to continue investing resources (Latham and Locke, 2007). Consequently, they may decide to stop and later resume goal pursuit once they have available or useful resources (Zeelenberg et al., 2000), or they may discard their initial ambition and change to an alternative goal.

Individuals are involved in multiple domains, such as the workplace and home, and they normally make daily transitions across and mobilize their limited personal resources to fit their personal demands in these domains (Clark, 2000). Existing studies have found that individuals are strategic in the way they determine their resource investment and utilization (Halbesleben et al., 2014). When personal resources in one domain (e.g., home) are useful in another domain (e.g., work), individuals may use these resources in a cross-domain manner. Therefore, it is conceivable that personal resources at home may positively contribute to activities in the work domain by helping reduce or even eliminate personal demands at work. In support of this argument, empirical studies have found that energy gained from non-work activities increases work engagement the subsequent day (Breevaart et al., 2019) and that when resources acquired at home can address demands faced at work, these resources help improve individuals’ performance at work (e.g., Voydanoff, 2005). Similarly, Greenhaus and Powell (2006) claim that resources such as skills and knowledge, psychological and physical resources, social capital resources, flexibility, and material resources that are obtained in the home domain may increase individuals’ persistence and resilience in the face of struggles and difficulties at work (Seligman, 1991, 2002). Friedman and Greenhaus (2000) report that information provided by an employee’s spouse may be used by the employee at work to solve relevant work challenges. Edwards and Rothbard (2000) maintained that a positive model experienced at home may improve individuals’ cognitive functioning at work. This may help improve individuals’ ability to solve work-related demands in the work domain. Additionally, home members may adopt the customer perspective and share with an individual their ideas that may improve negative customer contacts and provide suggestions on how to manage these contacts, which allows the individual to better address these issues at work. For individuals facing exessive intensity and amounts of work, home members may assist these individuals directly or may provide skills or tips to improve time and schedule management to complete work in an efficient and effective manner.

Following COR theory, personal resources from the home domain may contribute to performance in the work domain. For example, many studies have shown that the social support individuals obtain at home may increase their positive affect at work (e.g., Caprara et al., 2006), their self-efficacy for relevant work tasks (e.g., Xanthopoulou et al., 2007) and their intrinsic motivation to fully utilize all their abilities in pursuit of work objectives (e.g., Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Greenhaus and Powell (2006) revealed that individuals may use financial resources, such as no-interest loans and inheritance, to initiate or upgrade a business venture, to participate in a social network that helps boost business opportunities, or to take vocational-related courses to refine their work abilities.

Based on the above, it is likely that individuals enjoy reduced personal demands or increased personal resources at work, and they thus become better positioned to manage these resources at work. In line with COR theory, this may in turn motivate them to be more willing to invest these resources for additional resources that can be achieved by engaging in work, which consequently improves their work engagement level. Many studies have shown supportive findings, although a few have found insignificant evidence (e.g., Montgomery et al., 2003). For example, Bakker et al. (2005) surveyed 323 couples working in a variety of occupations and found that autonomy and social support gained at home can increase vigor at work. Lu et al. (2011a) surveyed a sample of 279 Chinese female nurses and revealed that resources received at home (e.g., family mastery) helped individuals stay engaged in the workplace. Bakker and Demerouti (2009) surveyed 175 Dutch women and their partners working in different occupational sectors as well as 175 colleagues of the male participants. They found that perceived spousal empathy benefits work engagement. In light of the above, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Personal demands at work mediate the positive relationship between personal resources at home and work engagement (home-to-work enrichment).

Hypothesis 2

Personal resources at work mediate the positive relationship between personal resources at home and work engagement (home-to-work resource gain spiral).

Individuals may be affected by personal demands in a cross-domain manner. The personal demands to which individuals are exposed in one domain may not only require individuals to deploy their personal resources in that domain but also offer the possibility that they need to utilize their personal resources from another domain. In such a case, it is conceivable that personal demands at home may negatively interfere with the work domain by eliminating personal resources at work. Existing studies have found that demands experienced at home (e.g., childcare and family demands) may deplete individuals’ available resources at work, such as time (e.g., Grandey and Cropanzano, 1999), a positive state at work (e.g., Lu et al., 2015), physical energy at work (e.g., Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012a,b), and well-being at work (e.g., Xu and Cao, 2019). According to COR theory, personal demands at home may increase the negative effects of personal demands at work because home demands can deplete available personal resources that could otherwise be deployed at work. As a result, personal demands at work accumulate. Empirical studies have shown that experiencing distress and overload in the family predicts distress and overload at work (e.g., Frone et al., 1997), that experiencing negative affect at home increases the stress level at work (e.g., Lu et al., 2015), and that the negative interference of a non-work domain with a work domain reduces satisfaction and well-being at work (e.g., Xu and Cao, 2019).

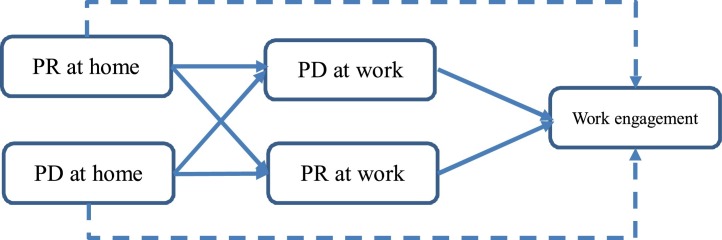

In light of the above, individuals may suffer from reduced personal resources or increased personal demands at work. In line with the asymmetrical bias regarding the experience of resource loss versus gain posited by COR theory, this may further encourage these individuals to enter a defensive mode to preserve remaining personal resources at work and consequently to become less engaged in work. They may also experience a stalemate of resource investment that results in a reduced level of engagement at work because they reduce or even stop their deployment of available personal resources. Many studies have shown that when individuals experience demands at home (e.g., home overload, emotional demands, cognitive demands, and quantitative demands), they reduce their vigor and dedication at work, which are two main elements of work engagement (e.g., Bakker et al., 2005; ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012a), work motivation (e.g., ten Brummelhuis et al., 2013), and work engagement (e.g., Karatepe et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019). We thus propose the following hypotheses. According to the proposed hypotheses, the research framework is depicted as Fig. 1 .

Hypothesis 3

Personal resources at work mediate the negative relationship between personal demands at home and work engagement (home-to-work conflict).

Hypothesis 4

Personal demands at work mediate the negative relationship between personal demands at home and work engagement (home-to-work resource loss spiral).

Fig. 1.

Research framework.

Note: The dotted lines are the direct effects that are not part of the study hypotheses.

PR: personal resources; PD: personal demands.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and procedure

We conducted a daily diary survey in a group of employees in 14 settings representing a range of different services, including restaurants [N = 2], coffee/tea shops [N = 4], hotels [N = 2], and clothing [N = 3] and convenience stores [N = 3] in China. China is characterized by a strong family culture that makes the home and work domains closely interconnected (Lee and Knobf, 2016). Hence, issues from home may affect both individuals’ home life and their effective functioning at work (Du et al., 2018). The use of daily diary surveys is appropriate in this study because individuals’ personal demands and personal resources across their living domains may fluctuate, causing their work engagement to also fluctuate over time (e.g., on a daily basis; Petrou et al., 2012). The fluctuation of resources is a premise of COR theory, and this fluctuation may include within-person changes (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Hence, we are interested in the daily effects of personal demands/resources at home and at work on individuals’ daily work engagement. We investigated the effects of (the prior day’s) personal resources and personal demands at home on (the next day’s) work engagement through (the next day’s) personal resources and personal demands at work. The daily diary design helped us capture the potential day-to-day fluctuations of our focal variables (Du et al., 2018). The participating businesses were privately owned and all employees in each were supervised by the same manager. Before administering the survey, we approached each manager, explained the purpose of this study, and requested their permission to survey their employees as well as their consent to participate. Managers and employees were informed that their responses would be anonymous, that the data collected would remain confidential and that their participation was voluntary. To increase the participation rate and acquire as much usable returned data with full participation as possible, we provided a lottery incentive of a prize of 100 RMB to individuals who fully participated in the survey (i.e., provided the necessary number of completed baseline and diary survey responses).

We collected two types of data: data from a baseline survey and data from several daily diary surveys. Paper-and-pencil data collection was used. We first invited all respondents to complete the baseline survey on the first survey day before the end of their work shift. Then, we invited them to complete the daily diary questionnaire for personal resources and demands at home before going to bed. The next day, we invited them to complete the daily diary questionnaire for personal resources and demands at work at the end of their work shift. For all questionnaires, we asked the participants to create their own research ID that was easy to remember yet anonymous to ensure their anonymity while allowing us to link successive diary responses to specific respondents. Respondents were asked to seal their completed questionnaires in envelopes, indicate the time on the envelopes and submit the envelopes to one of two prepared boxes at the beginning of their shift (for the daily diary questionnaire measuring personal resources and demands at home the previous day) and right before leaving work (for the daily diary questionnaire for personal resources and demands at work).

The participants’ managers or supervisors were invited to evaluate their employees’ daily work engagement whenever an employee finished work and left the workplace, put each completed questionnaire into a sealable envelope, indicated the time when the questionnaire was finished on the envelope, and inserted the envelope into the third envelope-shaped box we prepared, where retrieval was unlikely. The second and third boxes helped us effectively link the respondents’ daily response regarding personal demands and resources at work to their daily work engagement questionnaire rated by their manager or supervisor on a specific day, as all envelopes in the two boxes on the day were in the same order. To ensure managers’ or supervisors’ cooperation, we guaranteed to provide 200 RMB at the end of the survey for fully following the above requirements in the survey. The survey lasted 2 consecutive work weeks (i.e., 14 consecutive workdays) because as is common in China, the participants worked seven days a week. A total of 121 employees in the different organizations were invited to participate in the voluntary diary study, and 104 agreed to participate in the survey (response rate of 85.9%).

A total of 97 completed and usable survey packages were returned, which yielded an effective response rate of 80.2% (n = 97 for baseline questionnaire; n = 1358 for daily questionnaire). Over half (52%) of the respondents were male. Most of the respondents’ ages ranged from 26 to 30 years (34%) and then 31–35 years (23%). 30% of the respondents worked in a private restaurant, 24% in a private hotel, and 21% in a private coffee/tea shop. Most of the respondents either lived with roommates/friends (26%) or parents (25%). Forty-four percent of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree, 35% had completed some college, and 15% had completed secondary school. Most of the respondents worked 4–6 h per day (60%); many others worked 2–4 h per day (37%).

3.2. Measures

We selected personal resources and personal demands at work by interviewing managers and selected resources and demands at home through discussion with employees. We summarize the selected measures below. Where needed, we adapted the questionnaire items of established instruments by including appropriate terminology used in the specific research setting (e.g., “colleagues/manager(s)”; “home members”) and by referring to specific time periods (e.g., “today” and “yesterday” for daily measures). Additionally, all measures in this study were translated into Chinese from English. We adopted a back-translation procedure performed by one professional Chinese translator and one native English-speaker who were colleagues of the first author to ensure the accuracy of the meaning of all measurement items (Brislin, 1980).

3.2.1. Daily personal resources at work

The daily positive team climate at work (average α = .70) was measured by applying a 2-item scale developed by Xanthopoulou et al. (2009a). A sample item is “Today during the shift, there was a very good working atmosphere” (1=Strongly disagree, 4=Strongly agree). Daily colleague/manager social support (average α = .84; X2/df = 35.20; GFI = .98; AGFI = .87; RMR = .03) was measured using the 4-item scale from Peeters et al. (1995). A sample item is “Today during the shift, my colleagues/manager(s) paid attention to my feelings and problems” (1=Never, 4=Always).

3.2.2. Daily personal demands at work

Daily negative customer contact (average α = .71) was measured by adapting the 3-item scale developed by Consiglio et al. (2013). A sample item is “Today during the shift, customers were often impolite to me without any reason” (1=Strongly disagree, 4=Strongly agree). Excessive intensity and amount of work (average α = .90; X2/df = .65; GFI = .95; AGFI = .96; RMR = .01) was measured by adapting the 4-item scale from the job content questionnaire (JCQ) (Karasek, 1985). A sample item is “Today during the shift, my job required working excessively fast and/or hard” (1=Strongly disagree, 4=Strongly agree).

3.2.3. Daily personal resources at home

Daily personal life resources (average α = .82) were measured by adapting a 3-item scale used by Wayne et al. (2006). For example, we revised the original item, “Having a successful day at home puts me in a good mood to better handle my work responsibilities,” which originated with Stephens et al. (1997), to “Yesterday, things I did at home were great” (1=Strongly disagree, 5=Strongly agree) to filter out any explicit suggestions of links to work. Daily home life social support (average α = .72; X2/df = 58.34; GFI = .93; AGFI = .91; RMR = .05) was measured in the same way as daily colleague/manager social support. A sample item is “Yesterday, my home members paid attention to my feelings and problems” (1=Never, 5=Always).

3.2.4. Daily personal demands at home

Daily personal life duty (average α = .76; X2/df = 66.91; GFI = .95; GFI = .97; RMR = .05) was measured by adapting and revising the 4-item scale developed by Gutek et al. (1991). For example, we revised an original item, “I'm often too tired at work because of the things I have to do at home,” to “Yesterday, I had a lot of things to do at home” (1=Strongly disagree, 5=Strongly agree). Daily demands from contacts/interactions with individuals at home (average α = .82; X2/df = 32.31; GFI = .97; AGFI = .90; RMR = .04) were measured by adapting and revising the 4-item scale developed by Schuster et al. (1990). For example, we revised an original item, “How often do they criticize you?” to “Yesterday, people at home criticized me” (1=Never, 5=Always).

Daily work engagement (average α = .83; X2/df = 25.90; GFI = .95; AGFI = .86; RMR = .05) was measured with the daily version (6-item) of the UWES (Breevaart et al., 2012; Langelaan et al., 2006; Schaufeli et al., 2002), which contains two of the three original dimensions (i.e., daily vigor, daily dedication, and daily absorption). We excluded daily absorption for two reasons. First, according to Schaufeli and Bakker’s (2001) work after thirty in-depth interviews, unlike vigor and dedication, which were viewed as core elements of work engagement (Freeney and Fellenz, 2013), absorption was found to be a less relevant aspect of work engagement. Some recent studies further discarded absorption while evaluating work engagement (e.g., González-Romá et al., 2006). Second, a dairy study such as ours involves repeated measures. Short scales are crucial to avoid losing information due to participant attrition (Tims et al., 2011). A sample item for daily vigor is “Today, this employee was bursting with energy.” For daily dedication, a sample item is “Today, this employee was enthusiastic about his/her job” (1=Strongly disagree, 5=Strongly agree).

We included several demographic variables, such as age, educational background, occupation, and working hours per day. We follow Bernerth and Aguinis’s (2016) suggestion to provide evidence to justify the inclusion of these variables. Specifically, previous empirical research suggests a positive linkage between age and work engagement using socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen et al., 1999) and claims that due to the shift in the time perspective in later adulthood, older individuals tend to prefer positive emotional information and avoid negative emotional information. Thus, they focus more on the positive aspects of their job than on negative aspects and consequently experience higher work engagement than younger individuals (e.g., Goštautaitė and Bučiūnienė, 2015). Other studies suggest that differences in occupation affect work engagement from the perspective of demands and resources, indicating that various occupational settings have their own unique influences on employees’ work state and that the engagement level of employees may differ across occupations (e.g., Crawford et al., 2010).

Some studies also suggest that educational background/level is positively related to work state and performance using human capital theory (Sweetland, 1996). Studies find that work abilities/knowledge obtained by employees are likely to be rewarded with higher earnings in the labor market and that those who have higher educational levels are more likely to experience a positive work state and perform better than those who have lower educational levels (e.g., Ng and Feldman, 2009). Other studies suggest a negative relationship between working hours per day and work engagement based on resource scarcity theory, indicating that individuals’ available resources are limited and that continuous work depletes individuals’ resources such as energy, thereby reducing their work engagement (e.g., Gorgievski-Duijvesteijn and Bakker, 2010).

Given these relationships, it is possible that the elements that relate to work engagement may not stem from personal demands and resources at home and at work, as our theorizing suggests, but instead may stem from the impact of these control variables. Thus, to eliminate alternative explanations, to demonstrate the unique relationships between personal demands and resources at home and at work and work engagement, to maximize statistical power and to offer the most interpretable results, it is important to parse out the variance between these controls and our variables. We therefore control for these demographic variables (i.e., age, educational background, occupation, and working hours per day). We did not control for gender and cohabitants as there is insufficient empirical evidence and theoretical underpinning to justify their relationships with work engagement.

4. Analytic strategy

Using a diary study design, the structure of our collected data may be regarded as multilevel, with repeated daily diary evaluations nested within persons. This result in a two-level model with repeated evaluations (i.e., daily diary measures) at the first level (N = 1358 observations) and individual persons (i.e., baseline measure) at the second level (N = 97 employees). We adopted the Optimal Design program to perform the power analysis (Spybrook et al., 2011), and the results suggested adequate power for this study (value>.90). A multilevel model is a statistical model of parameters that vary at two or more levels, where lower-level data (e.g., daily observations) are nested within higher-level data (e.g., individual respondents) (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). Multilevel modeling extends ordinary regression analysis to the situation where the data are hierarchical (i.e., multilevel data; Leyland and Groenewegen, 2003). Therefore, we carried out multilevel mediation analysis in this study.

Considering that the sample size of this study was relatively small, we simplified the analytic measures by applying manifest variables, as suggested by Xanthopoulou et al. (2009b), and presented statistical evidence to support this application by performing multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (multilevel CFA). Before we examined the proposed hypotheses, we identified statistical support with the intraclass correlation (ρ) for the use of multilevel modeling (Tims et al., 2011). We adopted the Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling 7 (HLM 7) package to examine the proposed hypotheses. Following the suggestion of existing diary studies (e.g., Xanthopoulou et al., 2009b), the first-level (i.e., daily) variables were centered on the respective person mean, and the second-level (i.e., baseline) variables were centered on the sample mean before we examined the hypotheses. We further performed bootstrapping procedures with 20,000 Monte Carlo samples to test the proposed hypotheses (Preacher et al., 2010) in order to provide robust evidence for the significance and confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effects. Therefore, we presented the indirect effects, encompassing Monte Carlo confidence intervals, for the proposed hypothesis.

5. Results

To simplify the analytic measures, we conducted multilevel CFA to compare a 1st-order model in which sub-measures (e.g., daily positive team climate at work and daily colleague/manager social support) were represented as independent constructs with a 2nd-order model in which these sub-measures were indicators of one manifest (e.g., daily personal resources at work) variable. The results revealed that the 2nd-order model of each manifest variable fit significantly better than its 1st-order model (i.e., daily personal resources at work: ΔX2 = 3.866, df = 1, p < .05; daily personal demands at work: ΔX2 = 32.48, df = 1, p < .001; daily personal resources at home: ΔX2 = 69.59, df = 1, p < .001; daily personal demands at home: ΔX2 = 7.041, df = 1, p < .01; daily work engagement: ΔX2 = 745.834, df = 1, p < .001), which supported the representation of the sub-measures as one general manifest variable.

Table 1 provides the correlation results. Occupation (t = .24, p < .05), age (t = .27, p < .01), education (t = −.29, p < .05), and working hours (t = −.28, p < .05) were significantly related to daily work engagement. We controlled for these variables for later analysis. The intraclass correlation (ρ) results for focal measures based on the intercept-only model suggest that the multilevel structure of the data in this research must be considered when examining the proposed hypotheses (for daily work engagement: ρ = .11 [within-person variations: 89%], for daily personal demands at work: ρ = .16 [84%], for daily personal resources at work: ρ = .28 [72%], for daily personal demands at home: ρ = .30 [70%], and for daily personal resources at home: ρ = .25 [75%]).

Table 1.

Pearson correlation analysis results of all measures.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | 3.07 | 1.92 | – | |||||||

| Age | 3.68 | 1.27 | .20 | – | ||||||

| Education | 3.39 | .81 | −.03 | −.52*** | – | |||||

| Work HR (per day) | 2.59 | .64 | −.10 | .35*** | −.23** | – | ||||

| Work Engagement | 3.61 | .80 | .24* | .27** | −.29* | −.28** | – | |||

| PR at work | 2.45 | .65 | .30** | .14 | −.21* | −.04 | .11*** | – | ||

| PD at work | 3.04 | .55 | .05 | −.08 | .10 | −.28** | −.12*** | −.06* | – | |

| PR at home | 2.99 | .61 | .05 | −.28** | .08 | .02 | .08*** | .05* | −.06* | – |

| PD at home | 2.93 | .58 | .06 | .18 | −.01 | −.10 | −.09*** | −.05* | .06* | −.05* |

Note: *: p < .05; **: p < .01; ***: p < .001 (N = 1358 occasions, N = 97 participants).

Work HR = working hours; Work engagement = Daily work engagement (the averaged result based on daily work engagement across 14 consecutive surveyed workdays); PR = Personal resources; PD = Personal demands.

Table 2, Table 3 summarize the findings. Hypothesis 1 posits that personal demands at work mediate the positive relationship between personal resources at home and work engagement (home-to-work enrichment). The results in Table 2 (the first three models on the left) revealed that the inclusion of personal demands at work in the last model (Model 3a) caused the previously significant relationship (Model 2a) between personal resources at home and work engagement (t = .10, p < .01) to become less significant (t = .02, p < .05). Using a bootstrapping procedure with 20,000 Monte Carlo samples, the findings, as shown in Table 4 , support the indirect effects of personal demands at work (indirect effect = .01, CI 95% = [.003, .032]) on the relationship between personal resources at home and work engagement. The findings thus support Hypothesis 1.

Table 2.

Summary of multilevel estimate results (H1-H2).

| Model | 2a (DV: Personal demands at work) |

2a (DV: Daily work engagement) |

3a (DV: Daily work engagement) |

2b (DV: Personal resources at work) |

2b (DV: Daily work engagement) |

3b (DV: Daily work engagement) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t | Estimate | SE | t |

| Intercept | 3.04 | .02 | 123.94*** | 3.61 | .03 | 120.14*** | 3.61 | .03 | 120.14*** | 2.45 | .03 | 70.20*** | 3.61 | .03 | 120.14*** | 3.61 | .03 | 112.62*** |

| Occupations | .01 | .01 | .64 | .03 | .02 | 2.11* | .03 | .02 | 2.11* | .06 | .02 | 2.63** | .03 | .02 | 2.11* | .05 | .02 | 3.04** |

| Age | .01 | .02 | .47 | −.01 | .03 | −.23 | −.01 | .03 | −.23 | −.01 | .03 | −.18 | −.01 | .03 | −.23 | −.01 | .03 | −.15 |

| Education | .01 | .03 | .21 | −.01 | .04 | −.39 | −.01 | .04 | −.39 | −.01 | .05 | −2.02 | −.01 | .04 | −.39 | −.05 | .04 | −1.17 |

| Working Hour | −.10 | .04 | −2.15* | −.01 | .06 | −.12 | −.01 | .06 | −.12 | −.03 | .05 | −.69 | −.01 | .06 | −.12 | .04 | .06 | .64 |

| Home PR | −.13 | .03 | −1.16* | .10 | .03 | 2.75** | .02 | .03 | 1.62* | .07 | .03 | 1.50* | .10 | .03 | 2.75** | .09 | .03 | 2.63* |

| Work PD | −.12 | .05 | −2.50** | |||||||||||||||

| Home PD | ||||||||||||||||||

| Work PR | .10 | .04 | 2.54* | |||||||||||||||

| X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | |||||||||||||

| Level 1 (Daily) Variance | .26 | .56 | .56 | .31 | .56 | .56 | ||||||||||||

| Level 2 (General) Variance | .04 | 307.29*** | .05 | 212.06*** | .05 | 213.20*** | .10 | 512.32*** | .05 | 212.06*** | .07 | 242.51*** | ||||||

| −2 LL | 2112.63 | 3152.04 | 3117.65 | 2468.49 | 3152.04 | 3184.85 | ||||||||||||

| Δ-2 LL | 45.63** | 29.41* | 34.39*** | 4.48* | 29.41* | 4.20* | ||||||||||||

Note: *: p<.05**: p<.01***: p < .001 (N = 1358 occasions, N = 97 participants).

Home PD = Personal demands at home; Home PR = Personal resources at home; Work PD = Personal resources at work; Work PR = Personal resources at work.

The table only includes the last model of the needed analyses (the former three models on the left are for H1).

DV: dependent variable.

We treated the intercept as random and included a random slope for personal demands and personal resources at work and at home.

Table 3.

Summary of multilevel estimate results (con.) (H3-H4).

| Model | 2c (DV: Personal resources at work) |

2c (DV: Daily work engagement) |

3c (DV: Daily work engagement) |

2d (DV: Personal demands at work) |

2d (DV: Daily work engagement) |

3d (DV: Daily work engagement) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Est. | SE | t | Est. | SE | t | Est. | SE | t | Est. | SE | t | Est. | SE | t | Est. | SE | t |

| Intercept | 2.45 | .03 | 70.92*** | 3.61 | .03 | 120.14*** | 3.61 | .03 | 120.14*** | 3.04 | .02 | 121.90*** | 3.61 | .03 | 120.14*** | 3.61 | .03 | 112.62*** |

| Occupation | .05 | .02 | 2.25* | .03 | .02 | 2.11* | .03 | .02 | 2.11* | .01 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .02 | 2.11* | .05 | .02 | 3.04* |

| Age | −.01 | .03 | −.21 | −.01 | .03 | −.23 | −.01 | .03 | −.23 | .01 | .03 | .43 | −.01 | .03 | −.23 | −.01 | .03 | −.15 |

| Education | −.09 | .05 | −1.71 | −.01 | .04 | −.39 | −.01 | .04 | −.39 | .02 | .03 | .61 | −.01 | .04 | −.39 | −.05 | .04 | −1.17 |

| Working Hours | −.06 | .05 | −1.02 | −.01 | .06 | −.12 | −.01 | .06 | −.12 | −.11 | .04 | −2.53* | −.01 | .06 | −.12 | .04 | .06 | .64 |

| Home PR | ||||||||||||||||||

| Work PD | −.11 | .05 | −2.32* | |||||||||||||||

| Home PD | −.13 | .04 | −3.49** | −.17 | .04 | −3.50*** | −.13 | .04 | −2.29* | .12 | .05 | 1.40* | −.17 | .04 | −3.50*** | −.13 | .04 | −4.32* |

| Work PR | .18 | .04 | 3.15** | |||||||||||||||

| X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | |||||||||||||

| Level 1 (Daily) Variance | .31 | .56 | .55 | .26 | .56 | .55 | ||||||||||||

| Level 2 (General) Variance | .10 | 508.87*** | .05 | 214.25*** | .05 | 214.95*** | .05 | 318.70*** | .05 | 214.25*** | .07 | 244.93*** | ||||||

| −2 LL | 2445.08 | 3164.94 | 3130.40 | 2158.12 | 3164.94 | 3171.94 | ||||||||||||

| Δ-2 LL | 21.34** | 16.51** | 34.51*** | 1.55* | 16.51** | 4.02* | ||||||||||||

Note: *: p < .05**: p < .01***: p < .001 (N = 1358 occasions, N = 97 participants).

Home PD = Personal demands at home; Home PR = Personal resources at home; Work PD = Personal resources at work; Work PR = Personal resources at work.

The table includes only the last model of the needed analyses (the former three models on the left are for H3).

DV: dependent variable.

We treated the intercept as random and included a random slope for personal demands and personal resources at work and at home.

Table 4.

Results summary of confidence interval for the proposed hypotheses.

| Indirect paths | Bootstrapping |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | Indirect effect | 95% Confidence interval (Indirect effect) | |

| H1. Personal resources at home→Personal demands at work→Work engagement | .02* | .01 | [.003, .032] |

| H2. Personal resources at home→Personal resources at work→Work engagement | .02* | .01 | [.000, .020] |

| H3. Personal demands at home→Personal resources at work→Work engagement | −.13* | −.02 | [−.043, −.008] |

| H4 Personal demands at home→Personal demands at work→Work engagement | −.13* | −.01 | [−.033, −.0002] |

Note: *: p < .05 (N = 1358 occasions, N = 97 participants).

Bootstrap sample size = 10,000.

Hypothesis 2 posits that personal resources at work mediate the positive relationship between personal resources at home and work engagement (home-to-work resource gain spiral). The results in Table 2 (the last three models) revealed that the inclusion of personal resources at work in the last model (Model 3b) caused the previously significant relationship (Model 2b) between personal resources at home and work engagement (t = .10, p < .01) to become less significant (t = .09, p < .01). The findings of a bootstrapping procedure with 20,000 Monte Carlo samples, as shown in Table 4, support the indirect effects of personal resources at work (indirect effect = .01, CI 95% = [.000, .020]) on the relationship between personal resources at home and work engagement. The findings thus support Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 posits that personal resources at work mediate the negative relationship between personal demands at home and work engagement (home-to-work conflict). The results in Table 3 (the first three models on the left) revealed that the inclusion of personal resources at work in the last model (Model 3c) caused the previously significant relationship (Model 2c) between personal demands at home and work engagement (t = −.17, p < .001) to become less significant (t = −.13, p < .05). The results of a bootstrapping procedure with 20,000 Monte Carlo samples, as shown in Table 4, support the indirect effects of personal resources at work (indirect effect = −.02, CI 95% = [−.043, −.008]) on the relationship between personal demands at home and work engagement. The findings thus support Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4 posits that personal demands at work mediate the negative relationship between personal demands at home and work engagement (home-to-work resource loss spiral). The results in Table 3 (the latter three models) revealed that the inclusion of personal demands at work in the last model (Model 3d) caused the previously significant relationship (Model 2d) between personal resources at home and work engagement (t = −.17, p < .001) to become less significant (t = −.13, p < .05). The findings of a bootstrapping procedure with 20,000 Monte Carlo samples, as shown in Table 4, support the indirect effects of personal demands at work (indirect effect = −.01, CI 95% = [−.033, −.0002]) on the relationship between personal demands at home and work engagement.

6. Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether personal resources and personal demands at home affect the work engagement of service and hospitality employees through personal resources and personal demands at work. Using COR theory, we proposed four hypotheses that were further supported by the collected data. Our results showed that individuals’ personal resources at home reduced their personal demands (H1) and increased their personal resources (H2) at work, which in turn motivated them to engage in work. By contrast, individuals’ personal demands at home reduced their personal resources (H3) and increased their personal demands (H4) at work, which in turn made them lower their engagement level at work. Below, we will discuss the theoretical contribution and future research avenues, implications for practitioners, and research limitations.

6.1. Theoretical contributions and future research avenues

The main theoretical contribution of this study is that we extend existing understandings of why and how individuals become more engaged or less engaged in work. Conventional studies have focused on the impact of the environment (e.g., workplace or home) on individuals’ personal resources (e.g., energy or mental resilience) in work engagement. In other words, whether individuals engage in work depends on how many personal resources remain after being impacted by the environment. However, we claim that individuals may “decide” for themselves whether to engage in work. In our case, when individuals have increased personal resources at their disposal or reduced personal demands in the work domain due to the help of personal resources at home, they may be more likely to engage in work as a means to acquire additional resources. When they experience reduced personal resources at their disposal or increased personal demands in the work domain due to the negative impact of personal demands at home, they may become less engaged in work as a means to secure available personal resources.

These findings have important theoretical implications. We claim that individuals’ decreased engagement may not always be accompanied by psychological and physiological inability as a result of depleted personal resources (e.g., taxed energy), as claimed by conventional studies (e.g., ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012a; Xanthopoulou et al., 2008). Rather, individuals may have personal resources available that may help them maintain general effective functioning at work, which may further influence their job performance. Existing studies have mainly found that individuals’ reduced work engagement hinders job performance because individuals do not have available personal resources to invest in work (e.g., Xanthopoulou et al., 2009a). No previous study has investigated whether reduced work engagement caused by individuals’ decision to secure personal resources may have the same effect. Future research should investigate such relationships to further distinguish the roles of reduced work engagement due to depleted personal resources and secured personal resources at work. We also find that individuals’ engagement may not be due to their belief that they can perform the job effectively, as claimed by traditional studies; rather, it may be due to their aim of acquiring additional personal resources at work. Our claim is supported by existing findings that reveal that work engagement predicts increased job resources and decreased job demands (e.g., Bakker, 2018; Tims et al., 2016).

Our results extend the theories of family-to-work conflict and enrichment. The theory of family-to-work conflict has been criticized because it does not clearly identify the causal process that links the work and the home domains (Grandey and Cropanzano, 1999). By adopting insights from COR theory, we demonstrated the negative interference of the home domain with the work domain by revealing that individuals’ personal demands at home result in less engagement in work by either decreasing their personal resources at work or worsening their personal demands at work. In addition, we extend the theory of family-to-work enrichment by providing another enrichment process from home to work. Traditional views of family-to-work enrichment have suggested that resources obtained at home directly improve performance at work (Greenhaus and Powell, 2006). We find that family-to-work enrichment may occur when individuals’ personal resources at home are applicable in managing their personal demands at work or increasing their personal resources at work, which in turn motivates them to engage in work. Our proposed process may also help to explain why personal resources obtained in the home domain may contribute to work performance because work engagement is a strong predictor of work performance (e.g., Breevaart et al., 2016). Future research is recommended to investigate the role of work performance in our proposed process. This study partially echoes the need to use a single model to explain the concept of work-family conflict and enrichment by emphasizing the family-to-work perspective (ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012a). However, future studies could theoretically and empirically extend our research by including the work-to-family perspective and focusing on home engagement to examine the interference of personal demands and personal resources at work with those at home and how this process affects individuals’ home engagement. Such an extension of this work may allow researchers to test the effects of (the prior day’s) personal resources and personal demands at work on (the next day’s) home engagement through (the next day’s) personal resources and personal demands at home.

In addition to providing empirical evidence to support the role of personal resources in COR theory, we extend the theory by proposing personal demands that, together with reconceptualized personal resources, help to explicitly explain how the resource gain spiral and the resource loss spiral affect individuals’ decisions regarding resource investment (in the form of work engagement) in a cross-domain manner. For example, we demonstrated the resource gain spiral (at work) in ways such as the use of personal resources at home to address personal demands and enrich personal resources at work, which in turn allows individuals to invest available resources in work engagement. We demonstrated the resource loss spiral (at work) in ways such as the phenomenon by which personal demands at home deplete personal resources and worsen personal demands at work, which in turn makes individuals less willing to invest available resources in work engagement. The personal resources and personal demands approach may facilitate future research on related issues that may apply COR theory in a more observable way.

Although our results support many existing studies on family-to-work conflict/enrichment issues (e.g., Caprara et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2015; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007), they contradict some studies that have examined the links between personal resources and personal demands in home and work engagement (e.g., Montgomery et al., 2003). In these studies, home resources and home demands have neither a direct nor an indirect impact on individuals’ work engagement. We claim that one of the reasons for this interesting difference may be due to sample characteristics. The respondents in this study were Chinese service employees. For decades, many studies have documented a strong family culture in China (e.g., Lee and Knobf, 2016; Shek, 2006). Thus, Chinese employees may be more likely to be impacted by influences derived from the home, which makes family-to-work conflict and enrichment more significant and obvious. As our results indicate, both the direct and indirect impacts of personal demands and personal resources at home on employees’ work engagement reached significance, and the direct impacts of these demands and resources were greater than the indirect ones. These findings shed light on the fact that the role of family influence in Chinese employees’ work engagement is particularly crucial. Recent studies have revealed that there is a significant difference between Western and Chinese cultures (e.g., Hu et al., 2016). Therefore, it is recommended that future research employ two sets of samples, one from Western countries and the other from China, to reexamine our hypotheses and to compare the results or to consider cross-cultural variations by applying three-level hierarchical linear modeling (i.e., countries, person-level variables, and daily diary entries).

Finally, individuals may reduce their work engagement as a proactive response to facing decreased personal resources and/or increased personal demands at work. Therefore, whether a reduction in work engagement may further contribute to better psychological and physical health (due to preserved personal resources) in some cases, such as under the negative interference of home with work, is an interesting research question to further investigate as personal resources are essential elements for improving psychological and physical health (e.g., Presti et al., 2018). Although the question is outside the scope of this study, our theoretical claims indeed open relevant avenues for future research.

6.2. Implications for practitioners

The results of this study demonstrate that individuals’ levels of work engagement depend on their management of personal resources and personal demands across domains. Specifically, individuals may deploy personal resources gained from the home domain to amplify available personal resources or reduce personal demands at work. This in turn better positions them to manage available personal resources at work and can motivate them to invest these resources in gain spirals at work, which eventually improves their work engagement (Llorens et al., 2007). Nevertheless, when individuals face personal demands at home, they may deplete personal resources and hence have fewer personal resources at work. They may also experience greater personal demands at work. This may motivate them to enter a defensive mode to preserve remaining personal resources at work and eventually to become less engaged in work.

In general, our result suggest that managers in the service industry, especially in settings such as hospitality businesses where personal contact with customers is central for co-creating value and where emotional labor places additional demands on employees, need to be mindful of the role that cross-domain dynamics regarding personal resources and demands play for employee work engagement. Specifically, this study points out that employees are not just passively reacting to changes in their personal resources due to cross-domain effects, which reflects the environment-centered perspective implicitly applied by most existing studies (e.g., Lu et al., 2011b) in this field. Rather, the results suggest that work engagement may be at least in part the product of employees’ proactively managing personal demands and mobilizing personal resources across domains which highlights an individual-centered perspective. One pragmatic implication of this perspective would be that direct interventions such as highlighting the prosocial impact of service provision for customers or clients (e.g., Freeney and Fellenz, 2013) or providing transformational leadership (Zhu et al., 2009) may not only have a direct effect on work engagement by acting as additional job resources, but may also serve as an invitation or inducement to employees to deploy their personal resources gained from other domains in their job. Such suggestions go beyond available suggestions for managers that, reflecting an environment-centered perspective, focus on the importance of providing employees with work-related resources or minimizing work-related demands in improving employees’ work engagement (e.g., Jung and Yoon, 2018; Kalia and Verma, 2017; Kim and Koo, 2017; Nikolova et al., 2019; Wadhwa and Guthrie, 2018).

Moreover, based on our results, we suggest that managers of service and hospitality employees may motivate their employees to craft work related resources in a non-work domain such as home. This may be done by motivating them to perform leisure/home crafting where they become intrinsically motivated to pursue activities in a non-work domain that associate with goal setting, human connection, and personal growth and development aiming for acquiring resources through the activities to address the unfulfilled aspects at work (Petrou et al., 2017). This strategy is particularly valuable where opportunities for job crafting are low (Petrou et al., 2017) which is often a feature in many service and hospitality job environments. Thus, inducing employees to engage in leisure crafting may be a viable and valuable strategy for managerial interventions in highly structured service work environments. To further the positive impact of such interventions managers can initiate interaction opportunities and invite employees to share their experiences of leisure crafting with each other. Empirical evidence that individuals may seek fulfillment via other’s experience of performing leisure crafting when they share similar motivation or common goals (e.g., Berg et al., 2010) supports this approach.

Finally, actively valuing employees efforts to fully engage with their home domain, for example through supporting employee leisure crafting, can have additional benefits for employee work engagement through supporting effective recovery from work (e.g., Sonnentag et al., 2008) which is facilitated through effective disengagement. Moreover, by fully valuing employee engagement with their home domain it is easier for managers to invoke reciprocity and thus to invite employees to switch mental gears for effective re-engagement with work at the beginning of their workday which has beneficial effects for employee work engagement (Sonnentag and Kühnel, 2016).

In sum, these three approaches can contribute to help motivate employees to increase their personal resources and decrease personal demands at home that may contribute to work engagement through increasing personal resources and minimizing personal demands at work.”

6.3. Research limitations

Some limitations should be reported. First, the participants’ responses may have been affected by the repetitive nature of the diary study design (Bolger et al., 2003). Respondents were asked to complete the same survey for seven days per week over two weeks, which may have led to habituation effects in the responses. The presence of substantial within-person fluctuations in the daily variables through the intraclass correlation analysis suggests that habituation effects, if present, appear to have been very limited and did not influence the results of this research in substantial ways (see Tims et al., 2011).

Second, as in many diary studies, the sample size of this multi-level study appears quite small at the higher level of participants in light of the number of predictor variables, which can lead to bias during analysis. The reason why the number of participants in this and many other diary studies is comparatively small is because respondents must complete daily diary questionnaires across many days, which is time consuming and requires strong commitment. Such a research design normally reduces the participation rate of surveys, which has happened in many existing diary studies (e.g., Bakker and Bal, 2010; Xanthopoulou et al., 2008). However, as the effective sample size for many relevant parameters in multilevel analyses is determined as the product of the number of participants (n = 97) by the number of completed diary entries per participant (in this case 14), the sample size for some of the parameters is considerably larger (n = 1358). In addition, to address potential problems arising from the number of participants, we simplified the analytic measures by applying manifest variables before testing the proposed hypotheses (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1993) that could prevent this study from losing information (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009b). Maas and Hox (2005) suggest a minimum sample for multilevel studies at the highest level of 30 cases, which this study clearly exceeds. The actual higher-level sample size (N = 97) in this study compares favorably with this minimum requirement and is likely to produce robust estimations. Importantly, the power analysis we performed by using the Optimal Design Plus Empirical Evidence program (Spybrook et al., 2011) revealed adequate power for this study (value>.90). Therefore, it is unlikely that our findings are solely or even largely attributable to method bias. Future research should attempt to employ further samples of sufficient size to confirm the results reported here. In addition, because we applied manifest variables for analysis, we did not examine each specific personal demand and personal resource at home and at work. Such an analysis may provide additional insights, especially with regard to the implications for practitioners. We suggest that future research should directly investigate these specific elements with larger samples.

Third, we did not investigate burnout as a potential outcome. Burnout and work engagement have been viewed as distinct but related opposite constructs, and it is suggested that they be measured separately (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Recent studies have revealed that Chinese employees may suffer from burnout issues at work (e.g., Hu et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2018). Although most of the evidence is based on work-related influences, some studies have found that the conflict between work and family may be one of the causes of Chinese employees’ burnout (e.g., Pu et al., 2017). This finding opens two potential research avenues. First, in this study, we claim that individuals may make decisions to reduce or stop investing their available personal resources when they find that resource investment is difficult. This implies that there may be a third variable (moderator) that we did not include that pushes them to continue investing their remaining personal resources. A potential variable worth investigation may be Chinese collectivism, another traditional aspect of culture in China that makes many Chinese employees prefer to work as a team rather than as individuals and that motivates them to care about team welfare more than their own (Brown et al., 2018). In other words, companies with strong Chinese collectivism may potentially motivate individuals who have personal demands at home to continue investing personal resources even if they find that resource investment at work is difficult, which eventually leads to burnout. The second research avenue would be to investigate whether personal resources at home may alleviate burnout by reducing personal demands at work and increasing personal resources at work.

Finally, the specific operationalizations of key study variables such as personal resources and personal demands arising in the home environment are a potential limitation, as the range of potentially relevant personal resources is very broad (see Hobfoll et al., 2018; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Thus, the findings provide an initial test of the hypothesized relationships. Further investigations that consider a broader range of resources and demands arising in the home domain will help test and confirm the initial results reported here and will provide deeper insights into the relationships between the home and work domains investigated in this study.

7. Conclusion

The present study discussed whether changes in work engagement may be based on individuals’ decisions to manage their personal resources. We investigated whether personal resources and personal demands at home affect work engagement through personal resources and personal demands at work. Empirical findings based on a group of Chinese employees from a range of various service settings support the theoretical claims of this study. Researchers may adopt several research avenues for further investigation of the dynamic of work engagement. Future research may also adopt our model as a blueprint to investigate potentially similar impacts of other non-work domains. Practitioners may use our findings as important support and guidance for managerial and organizational interventions that can change the way the home/work interface is managed and that can transform contemporary workplaces into healthier and more productive places for employees.

References

- Ali F., Amin M., Cobanoglu C. An integrated model of service experience, emotions, satisfaction, and price acceptance: an empirical analysis in the Chinese hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manage. 2016;25(4):449–475. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B. Job crafting among health care professionals: the role of work engagement. J. Nurs. Manage. 2018;26:321–331. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Bal M.P. Weekly work engagement and performance: a study among starting teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010;83(1):189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. The crossover of work engagement between working couples: a closer look at the role of empathy. J. Manage. Psychol. 2009;24(3):220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Schaufeli W.B. The crossover of burnout and work engagement among working couples. Hum. Relat. 2005;58:661–689. [Google Scholar]

- Berg J.M., Grant A.M., Johnson V. When callings are calling: crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organ. Sci. 2010;21(5):973–994. [Google Scholar]

- Bernerth J.B., Aguinis H. A critical review and best‐practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers. Psychol. 2016;69(1):229–283. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N., Davis A., Rafaeli E. Diary methods: capturing life as it is lived. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart K., Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Hetland J. The measurement of state work engagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2012;28:305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart K., Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Derks D. Who takes the lead? A multi-source diary study on leadership, work engagement, and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2016;37(3):309–325. [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart K., Bakker A.B., Derks D., van Vuuren T.C.V. Engagement during demanding workdays: a diary study on energy gained from off-job activities. Int. J. Stress Manage. 2019;27(1):45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In: Triandis H.C., Berry J.W., editors. vol. 2. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 1980. pp. 389–444. (Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology). [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.D., Hallam P.R., Qin T. Propensity to trust and trust development among Chinese university students. World Stud. Educ. 2018;18(2):25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara G.V., Steca P., Gerbino M., Pacielloi M., Vecchio G.M. Looking for adolescents’ well-being: self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of positive thinking and happiness. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2006;15:30–43. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L.L., Isaacowitz D.M., Charles S.T. Taking time seriously: a theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999;54(3):165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Does work engagement mediate the influence of job resourcefulness on job crafting? An examination of frontline hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2019;31(4):1684–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Chen C. Job resourcefulness, work engagement and prosocial service behaviors in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2017;29(10):2668–2687. [Google Scholar]

- Clark S.C. Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance. Hum. Relat. 2000;53(6):747–770. [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio C., Borgogni L., Alessandri G., Schaufeli W.B. Does self-efficacy matter for burnout and sickness absenteeism? The mediating role of demands and resources at the individual and team levels. Work Stress. 2013;27:22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Conway E., Fu N., Monks K., Alfes K., Bailey C. Demands or resources? The relationship between HR practices, employee engagement, and emotional exhaustion within a hybrid model of employment relations. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2016;55(5):901–917. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford E.R., LePine J.A., Rich B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: a theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010;95(5):834–848. doi: 10.1037/a0019364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Bakker A.B., Voydanoff P. Does home life interfere with or facilitate job performance? Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2010;19(2):128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Sanz-Vergel A.I., Petrou P., van den Heuvel M. How work–self conflict/facilitation influences exhaustion and task performance: a three-wave study on the role of personal resources. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016;21(4):391–402. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D., Derks D., Bakker A.B. Daily spillover from family to work: a test of the work–home resources model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018;23(2):237. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J.R., Rothbard N.P. Mechanisms linking work and family: clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2000;25:178–199. [Google Scholar]