Abstract

Stenting for severely calcified lesions has a higher risk of stent restenosis or stent failure than stenting for lesions without calcification, and stenting for complex lesions including ostial or bifurcation lesions sometimes causes plaque shift which leads to side branch occlusion. A calcified nodule (CN) is considered one of the culprits for stable angina or acute coronary syndrome. However, the optimal strategy for this lesion is not well clarified. We report a patient who presented stable angina with a CN at the ostial left circumflex artery. In this case, pretreatment with excimer laser coronary atherectomy (ELCA) and scoring balloon dilatation followed by drug-coated balloon (DCB) dilatation successfully prevented plaque shift caused by stenting in the acute phase. In addition, it also maintained the patency in the late phase. Furthermore, we observed the CN lesions at preprocedural, postprocedural, and late phase by optical coherence tomography. ELCA, which has a unique debulking technique, and scoring balloon dilatation followed by DCB dilatation might offer an alternative treatment for ostial CN lesions instead of stenting.

〈Learning objective: The optimal strategy for severely calcified lesions with calcified nodule is controversial because the prevalence of calcified nodule is rare and stent failure is more common in calcified lesions. In particular, regarding a calcified nodule located in ostial left circumflex coronary artery lesion, excimer laser coronary atherectomy and scoring balloon dilatation followed by drug-coated balloon may give an alternative treatment to avoid stenting.〉

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Calcified nodule, Excimer laser coronary atherectomy, Drug-coated balloon

Introduction

In percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures, stenting at complex lesions with severe calcification could result in stent restenosis and stent failure more often than those without. Therefore, coronary interventionists should pay close attention to the use of stents in complex lesions involving a bifurcation and severe calcification [1]. Notably, a calcified nodule (CN), which is a type of calcified plaque, is often responsible for stable angina or acute coronary syndrome. However, the probability of its occurrence is comparably low [2], and the optimal therapy for these lesions is not well clarified [3]. We report a patient who presented with stable angina with a CN at the ostial left circumflex artery (LCX). We successfully performed lesion modification with excimer laser coronary atherectomy (ELCA) and scoring balloon dilatation, followed by PCI with drug-coated balloon (DCB) dilatation and optical frequency domain imaging (OFDI).

Case report

The patient, a 71-year-old-man, presented to our hospital in December 2014 with exertional angina. The patient characteristics are displayed in Supplemental Figure 1A and 1B. A coronary computer tomography angiogram showed heavy calcification in entire coronary vessels, and invasive coronary angiography (CAG) was performed in January 2015 (Fig. 1). CAG showed significant stenosis in the ostial LCX and distal right coronary artery (RCA). The lesion in the distal RCA was successfully treated with stenting first. After the PCI procedure, the occurrence of chest pain decreased, but exertional angina continued during long-distance walking. Subsequently, PCI for the ostial LCX was scheduled. CAG revealed heavily calcified coronary vessels and significant stenosis at the ostial LCX. Floating substances at the intracoronary lumens were thought to be CN (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Movie 1). To avoid left main coronary artery and LCX cross-over stenting, we considered a stent-less strategy. The left coronary artery was engaged by a 6Fr VL3.5 guide catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, US) from a right radial artery approach (Fig. 2B). A 0.014-in. guidewire (Sion Blue; Asahi Intec., Nagoya, Japan) is simply delivered across the target lesion, and another 0.014-in. guidewire (Runthrough NS; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced to the distal left anterior descending artery (LAD) to protect the LAD. An OFDI catheter (Fastview; Terumo) could not pass the lesion. After balloon pre-dilatation of a 1.75 mm × 15 mm PTCA catheter (CanPass; Japan Lifeline Co., Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 2C), OFDI examination was performed and its findings supported CN at ostial LCX. The minimum lumen area (MLA) was 0.95 mm2 (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Table 1, and Supplemental Movie 2). After the balloon dilatation, we performed ELCA to debulk the calcified plaque, including the CN (Fig. 2D and E). ELCA was performed with a Spectranetics CVX-300 System (Spectranetics, Colorado Springs, CO, USA), which is a XeCl excimer laser system. At first, a 0.9 mm concentric catheter of ELCA was advanced slowly at a speed of 0.2–0.5 mm/s across the lesion with a standard saline technique applied [4]. We started with a fluence of 60 mJ/mm and frequency of 40 Hz. Subsequently, a 1.4 mm concentric catheter of ELCA was used with the same fluence and frequency. After the ELCA, a 2.5 mm × 13 mm scoring balloon catheter (Lacrosse NSE alpha; Goodman Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan) was advanced for balloon dilatation (Fig. 2F), followed by a 2.5 mm × 15 mm paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter (Sequent Please; B Braun, Melsungen, Germany) at 7 atm for a minute (Fig. 2G). Just 5 min after PCI with DCB dilatation, the final CAG and OFDI findings showed a good lumen expansion without any acute restenosis, with thrombolysis in myocarcardial infarction grade 3 coronary flow (Fig. 2H and Supplemental Movie 3). Follow-up CAG was performed 3 months after the PCI, and it revealed no progression at this lesion (Fig. 2I). Furthermore, although distal RCA had catheter-revascularizations 3 years after the PCI for RCA with stenting, even CAG performed at this timing displayed that the treated ostial LCX lesion with a CN had no progression (Fig. 2J and Supplemental Fig. 2). In addition, we performed the follow-up optical coherence tomography (ILUMIEN, Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA) examination 3 months after the PCI for LCX. These findings displayed late lumen gain (MLA: 4.5 mm2) at the ostial LCX (Fig. 3, Supplemental Table 1, and Supplemental Movie 4).

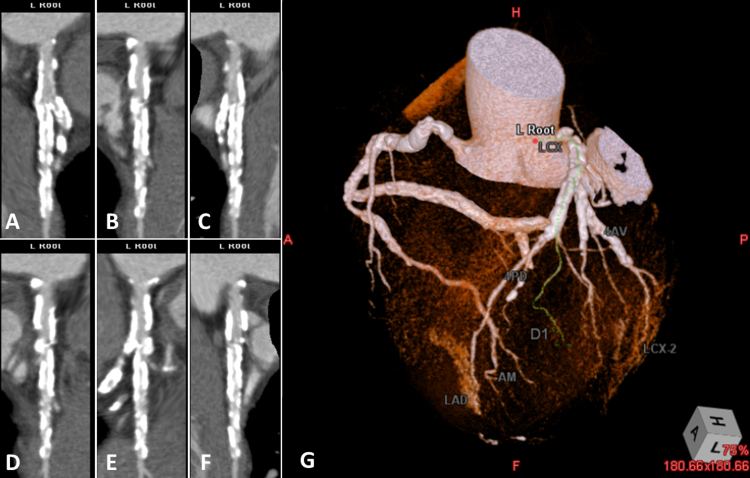

Fig. 1.

Coronary computed tomography angiogram displayed severe calcification in all coronary vessels. (A–F) Multi-planar reconstruction of LCX. (G) Volume rendering of coronary vessels.

LCX, left circumflex artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; D, diagonal branch; AM, acute marginal branch; AV, atrioventricular node branch; PD, posterior descending branch.

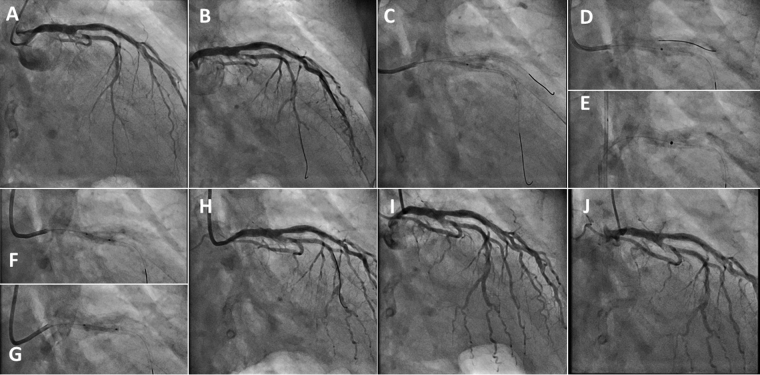

Fig. 2.

Coronary angiography. (A) An angiogram at the baseline showed significant stenosis with a CN at the ostial LCX. (B) The systems are shown. Guide catheter: 6Fr VL3.5 guide catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA); LCX: a 0.014-in. guidewire (Sion Blue; Asahi Intec., Nagoya, Japan); LAD: a 0.014-in. guidewire (Runthrough NS; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). (C) The balloon dilatation of a 1.75 mm × 15 mm PTCA catheter (canPass; Japan Lifeline Co., Tokyo, Japan). (D) A 0.9 mm concentric catheter of excimer laser coronary atherectomy. (E) A 1.4 mm concentric catheter of excimer laser coronary atherectomy. (F) The dilatation of a 2.5 mm × 13 mm scoring balloon catheter (Lacrosse NSE alpha; Goodman Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan). (G) The dilatation of 2.5 mm × 15 mm paclitaxel courted balloon catheter (Sequent Please; B Braun, Melsungen, Germany). (H) Final CAG at the PCI. (I) Follow-up CAG performed 3 months after the PCI. Restenosis at LCX was not identified without coronary flow limitation. (J) Follow-up CAG performed 3 years after the PCI. Restenosis at LCX was not identified without coronary flow limitation.

CN, calcified nodule; LCX, left circumflex artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; CAG, coronary angiography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Fig. 3.

Time sequences of optical frequency domain imaging or optical coherence tomography imaging of the culprit lesion. (A) After balloon dilatation of a 1.75 mm × 15 mm PTCA catheter. (B) Final optical frequency domain imaging at the PCI. (C) Follow-up optical coherence tomography imaging performed 3 months after the PCI.

PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

In this case, the culprit lesion had two characteristics. One is that the lesion morphology was a CN with severe calcified plaque. The other is that the target lesion existed in the ostial LCX. A CN is a cause of stable angina or acute coronary syndrome. Lee et al. reported that CNs have a tendency to exist in the ostial or middle RCA with tortuosity, and that one-third of acute coronary syndrome lesions with severe calcified plaque had a CN [2]. In addition, it has been shown that a CN increases the risk of stent failure both in the early and late phases [3]. However, the optimal strategy for a CN lesion remains unclear because the occurrence of a CN is so rare that it has been detected in only 4.2% of all lesions [2]. Therefore, further studies are expected.

As ostial LCX lesions have characteristics of ostium and bifurcation, interventionists should be particularly careful during PCI because ostial LCX lesions carry a risk of LAD stenosis or occlusion during balloon dilatation or stenting [5]. Besides, stenting at lesions including the ostial LCX and left main coronary artery has a risk of side branch occlusion caused by plaque shift giving rise to a large periprocedural myocardial infarction [5]. To circumvent this complication, post-balloon dilatation procedures, such as the balloon-stent kissing technique or the modified balloon-stent kissing technique, are often applied [6]. In addition, because the calcification in this lesion was so severe, stent failure was far more likely to occur. This is why we hesitated to use the strategy of cross-over stenting from the left main coronary artery to the LCX.

Conversely, recent studies, including a systematic review, showed feasible clinical outcomes for a stent-less strategy for de-novo lesions [7]. This strategy takes advantage of DCB only, without stenting. Although there is no evidence that the DCB only strategy is superior to the stenting strategy in all lesions, Kleber et al. said that this is a useful strategy for bifurcation lesions that show only class A or B dissection and recoil not beyond 30% [8]. Moreover, OFDI is useful in assessing coronary dissection occurrence in bifurcation lesions because of what OFDI reveals about lumen circumferences [9]. Consequently, we applied the DCB-only strategy, and this strategy provided not only acute lumen gain but also late lumen gain. OCT findings at 3 months after the PCI supported this interesting phenomenon thought to be thanks to positive remodeling and partially healed CN plaque compared at post-procedure of the PCI.

In this case, ELCA and the scoring balloon dilatation were performed to debulk plaques and modify the lesion before DCB. ELCA was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for complex lesions including ostial lesions and moderately calcified lesions. In addition, ELCA is also safely applied in severely calcified lesions, and a previous report showed the feasible results of ELCA to CNs [10]. Moreover, ELCA allows the delivery of two guidewires with resultant protection of the bifurcation vessels during the debulking procedure, and this point implies the advantage in ostial lesion compared with other debulking devices. Thus, this case was consistent with the lesions mentioned above. We also performed the scoring balloon dilatation for lesion modification, which has also been utilized for severe calcified lesions because it can achieve more lumen gain than conventional balloon dilatation. Recently, coronary intravascular lithotripsy system has got an approval for CE mark, and its effectiveness for calcified lesions including CNs would be examined in the latest studies. Although rotational atherectomy or orbital atherectomy may be efficacious in such a CN lesion, these debulking devices have a risk of insufficient touch by wire bias which ELCA enables to resolve using an eccentric-ELCA-catheter instead of a concentric one. In this case, rotational atherectomy was an only alternative method to debulk CN at that time because orbital atherectomy had not been approved in Japan.

In conclusion, severely calcified lesions with a CN in ostial LCX is complex to treat, but we successfully treated it with the lesion modification of ELCA and the scoring balloon dilatation followed by DCB, utilizing OFDI. Its patency continued for more than three years. PCI with DCB, after plaque modification with ELCA and scoring balloon dilatation, might be an alternative treatment for ostial CN lesions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest concerning this case study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccase.2020.04.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Jiangang Z., Shuai L., Tao G., Zesheng X. One-stent versus two-stent techniques for distal unprotected left main coronary artery bifurcation lesions. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:14363–14370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee T., Mintz G.S., Matsumura M., Zhang W., Cao Y., Usui E. Prevalence, predictors and clinical presentation of a calcified nodule as assessed by optical coherence tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori H., Finn A.V., Atkinson J.B., Lutter C., Narula J., Virmani R. Calcified nodule; an early and late cause of in-stent failure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e125–e126. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Topaz O., Lippincott R., Bellendir J., Taylor K., Reiser C. “Optimally spaced” excimer laser coronary catheters: performance analysis. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2001;1:9–14. doi: 10.1089/104454701750066884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeitouni M., Silvain J., Guendeney P., Kerneis M., Yan Y., Overtchouk P. Periprocedural myocardial infarction and injury in elective coronary stenting. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1100–1109. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Z., Li L., Wang M., Zhang S., Shen Z. Innovative provisional stenting approach to treat coronary bifurcation lesions: balloon-stent kissing technique. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25:600–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohiaddin H., Wong T.D.F.K., Burke-Gaffney A., Bogle R.G. Drug-coated balloon-only percutaneous coronary intervention for the treatment of de novo coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Cardiol Ther. 2018;7:127–149. doi: 10.1007/s40119-018-0121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleber F.X., Rittger H., Ludwig J., Schulz A., Mathey D.G., Boxberger M. Drug eluting balloons as stand alone procedure for coronary bifurcational lesions: results of the randomized multicenter PEPCAD-BIF trial. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016;105:613–621. doi: 10.1007/s00392-015-0957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longobardo L., Mattesini A., Valente S., Di Mario C. OCT-guided percutaneous coronary intervention in bifurcation lesions. Interv Cardiol Rev. 2019;14:5–9. doi: 10.15420/icr.2018.17.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashikaga T., Yoshikawa S., Isobe M. The efficacy of excimer laser pretreatment for calcified nodule in acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:197–200. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.