Summary

Immune escape contributes to viral persistence, yet little is known about human polyomaviruses. BK-polyomavirus (BKPyV) asymptomatically infects 90% of humans but causes premature allograft failure in kidney transplant patients. Despite virus-specific T cells and neutralizing antibodies, BKPyV persists in kidneys and evades immune control as evidenced by urinary shedding in immunocompetent individuals. Here, we report that BKPyV disrupts the mitochondrial network and membrane potential when expressing the 66aa-long agnoprotein during late replication. Agnoprotein is necessary and sufficient, using its amino-terminal and central domain for mitochondrial targeting and network disruption, respectively. Agnoprotein impairs nuclear IRF3-translocation, interferon-beta expression, and promotes p62/SQSTM1-mitophagy. Agnoprotein-mutant viruses unable to disrupt mitochondria show reduced replication and increased interferon-beta expression but can be rescued by type-I interferon blockade, TBK1-inhibition, or CoCl2-treatment. Mitochondrial fragmentation and p62/SQSTM1-autophagy occur in allograft biopsies of kidney transplant patients with BKPyV nephropathy. JCPyV and SV40 infection similarly disrupt mitochondrial networks, indicating a conserved mechanism facilitating polyomavirus persistence and post-transplant disease.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Immunology, Virology, Cell Biology

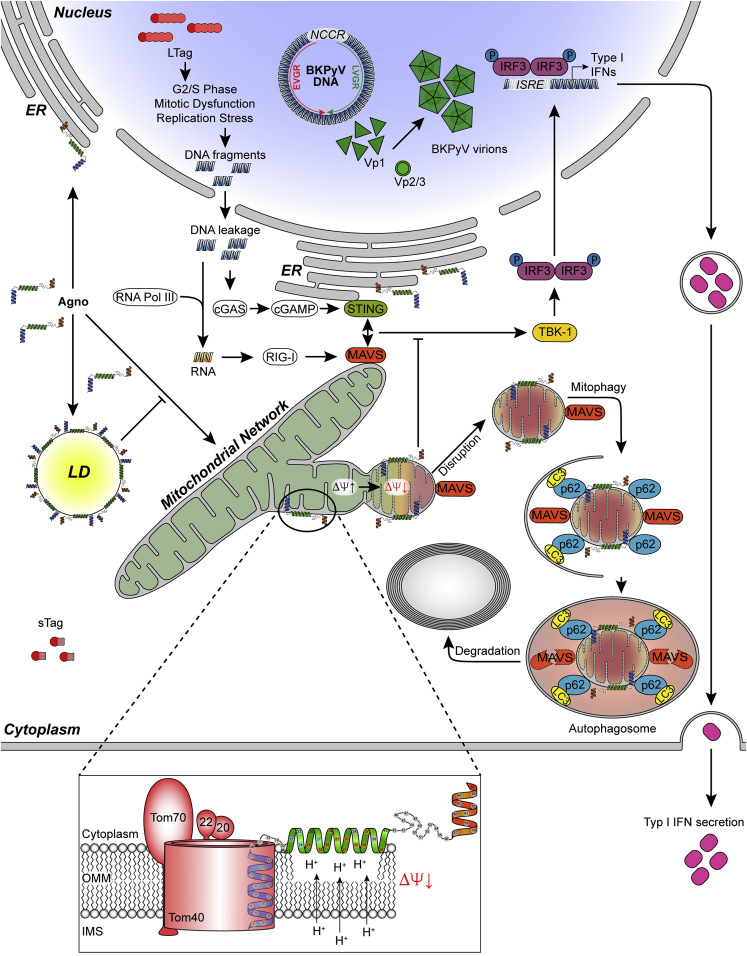

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

BK polyomavirus agnoprotein disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential and network

-

•

Agnoprotein impairs nucleus IRF3 translocation and interferon-β expression

-

•

Agnoprotein facilitates innate immune evasion during the late viral replication phase

-

•

Damaged mitochondria are targeted for p62/SQSTM1 autophagy

Biological Sciences; Immunology; Virology; Cell Biology

Introduction

Viruses infect all forms of life, and although metagenomics are revealing an increasing complexity of viromes (Hirsch, 2019, Simmonds et al., 2017, Virgin, 2014), the underlying principle remains the same: viral genetic information present as DNA or RNA is decoded by host cells, thereby enabling a programmed take-over of cell metabolism to accomplish the essential steps of viral genome replication, packaging, and progeny release to infect new susceptible cells and hosts (Enquist and Racaniello, 2013). With progeny rates ranging from ten to several hundred-thousands per cell, virus replication represents a severe burden compromising host cell function and viability and ultimately organ and host integrity. Host defense mechanisms include antiviral restriction factors (Kluge et al., 2015) as well as innate and adaptive immune responses (McNab et al., 2015) intercepting early and late steps of the viral life cycle. Given the obligatory intracellular location of virus replication, the innate immune response is faced with the challenge of discriminating virus and its regulatory and structural units as “non-self” amid physiological host cell constituents. This task is partly accomplished by identifying pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as repetitive protein, lipid, and sugar structures through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). In the last decade, cytoplasmic sensing of nucleic acids has emerged as a key mechanism of intracellular innate immune sensing (Takeuchi and Akira, 2010). Evolutionarily linked to detecting DNA damage and the failing integrity of nuclei or mitochondria associated with metabolic stress, toxicity, or cancer (Hartlova et al., 2015, Li and Chen, 2018, West and Shadel, 2017), viral RNA and DNA were found to be similarly sensed through PRRs such as RIG-I/MDA-5/MAVS and cGAS/STING (Goubau et al., 2013, Hartlova et al., 2015, McFadden et al., 2017). MAVS and STING have been located on membranous platforms of mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in the cytosol. Besides direct cross-talk (Zevini et al., 2017) and proximity via mitochondria-associated ER-membranes (MEM), both pathways converge in inducing type-1 interferon expression following the activation of the downstream kinases TBK-1 and IKKε and the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of transcription factors such as IRF3, IRF7, and NFkB (Liu et al., 2015, McFadden et al., 2017). Interferons are key mediators of the antiviral state in infected and neighboring cells and help to activate the adaptive antigen-specific immune responses (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2010, Schneider et al., 2014). Different molecular mechanisms of innate immune activation are induced in acute and chronic infections with human RNA or DNA viruses, and a variety of strategies has been described, which may permit transient or persistent viral evasion (Garcia-Sastre, 2017). However, such aspects are incompletely understood for small non-enveloped DNA viruses such as human polyomaviruses.

BK polyomavirus (BKPyV) is one of more than 10 human polyomaviruses and infects >90% of the general population typically during childhood without specific illness (Greenlee and Hirsch, 2017, DeCaprio et al., 2013). Although BKPyV induces potent virus-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells (Binggeli et al., 2007, Chen et al., 2008, Cioni et al., 2016, Leboeuf et al., 2017) and neutralizing antibodies (Kaur et al., 2019, Pastrana et al., 2012, Shah et al., 1980, Solis et al., 2018), the virus latently persists in the kidneys and regularly escapes from immune control as evidenced by asymptomatic urinary virus shedding in immunocompetent healthy individuals (Egli et al., 2009, Imperiale and Jiang, 2016). In immunosuppressed patients, BKPyV replication increases in rate and magnitude, progressing to hemorrhagic cystitis and nephropathy in 5%–25% and 1%–15% of allogeneic bone marrow transplant and kidney transplant recipients, respectively, and even urothelial cancer (Cesaro et al., 2018, Graf and Hirsch, 2020, Hirsch and Randhawa, 2019). Because specific antiviral agents and vaccines are not available, reducing immunosuppression is the current mainstay of therapy in order to regain control over BKPyV replication (Cesaro et al., 2018, Hirsch and Randhawa, 2019). However, this maneuver increases the risk of immunological injury such as allograft rejection or graft-versus-host disease. In our ongoing study to identify functionally and diagnostically relevant targets of BKPyV-specific antibody and T cell responses (Binggeli et al., 2007, Cioni et al., 2016, Leboeuf et al., 2017), we noted that the small BKPyV agnoprotein of 66 amino acids (aa) is abundantly expressed in the cytoplasm during the late viral life cycle in vitro and in vivo but largely ignored by the adaptive immunity (Leuenberger et al., 2007, Rinaldo et al., 1998). BKPyV agnoprotein co-localizes with lipid droplets (LD) (Unterstab et al., 2010) and membranous structures of the ER (Unterstab et al., 2013). We now report that the BKPyV agnoprotein also targets mitochondria and subverts interferon-β induction by disrupting the mitochondrial network and its membrane potential and promotes p62/SQSTM1 mitophagy in cell culture and in kidney allograft biopsies.

Results

BKPyV Agnoprotein Colocalizes with Mitochondria and Induces Mitochondrial Fragmentation

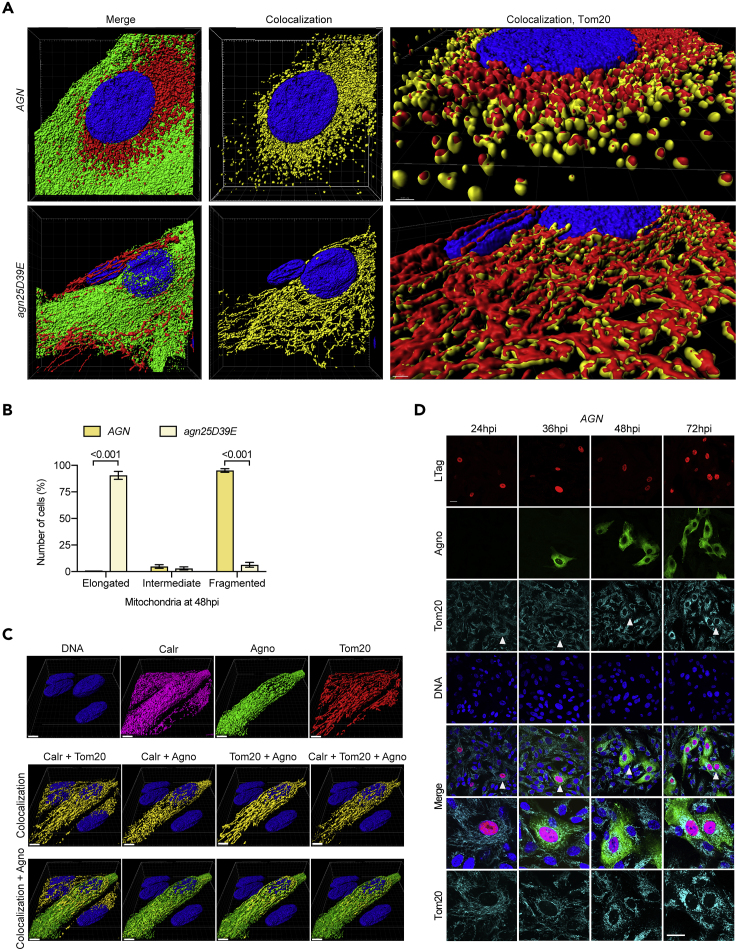

To elucidate the function of BKPyV agnoprotein in the absence of LD, we noted that the N-terminal amino acid (aa) sequence had similarity to mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) found in cytochrome c oxidase cox8 (Figure S1). To investigate the potential mitochondrial localization, we infected primary human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (RPTECs) with the agnoprotein wild-type BKPyV-Dunlop (Dun-AGN), a well-characterized model of renal allograft nephropathy (Bernhoff et al., 2008, Hirsch et al., 2016, Low et al., 2004). The results were compared with the isogenic derivative Dun-agn25D39E, of which the encoded point mutant agnoprotein is known to no longer bind to LD after replacing the hydrophobic A25 and F39 with D and E, respectively, abrogating the amphipathic character of the central agnoprotein domain without affecting the α-helix prediction (Unterstab et al., 2010).

At 48-h post-infection (hpi) with wild-type Dun-AGN and mutant Dun-agn25D39E viruses, immunofluorescent staining identified infected cells in the late viral replication phase by detecting both the early viral protein large T-antigen (LTag) and the late viral protein Vp1 capsid in the nucleus and agnoprotein in the cytoplasm (Figure S2). Using the mitochondrial outer membrane protein Tom20 as a marker, its specific colocalization with both the AGN wild-type and agn25D39E mutant protein was found, demonstrating agnoprotein colocalization to mitochondria (Figure 1A). However, the mitochondria of Dun-AGN-replicating RPTECs had lost the network-like pattern typical of uninfected cells and appeared in short, fragmented units (Figure 1A, Video S1). In contrast, Dun-agn25D39E-replicating RPTECs exhibited a regular mitochondrial network similar to neighboring uninfected cells (Figure 1A; Video S2). Quantification of the mitochondrial morphology indicated a large excess of short mitochondrial fragments in Dun-AGN-infected cells, whereas mostly elongated mitochondria in a network-like pattern were seen in the Dun-agn25D39E-infected cells (Figure 1B). Given these striking differences in mitochondrial phenotype, we examined whether or not the mutant agn25D39E-agnoprotein was still able to target the ER as reported for the wild-type agnoprotein (Unterstab et al., 2013). Confocal microscopy revealed that the agn25D39E protein colocalized with the ER marker calreticulin (Figure 1C). However, whereas the mitochondrial colocalization of the agn25D39E protein appeared in network strings, the ER colocalization with calreticulin was patchy and reminiscent of the contact sites with the mitochondria-associated membranes (MEMs) (Figure 1C). The patchy ER-colocalization pattern was independently confirmed using protein disulphide isomerase (PDI), another ER marker protein (Figure S2C). The results indicated that targeting of ER and mitochondria remained intact and implicated the amphipathic character of the central α-helix of the wild-type agnoprotein in the disruption of the mitochondrial network.

Figure 1.

Agnoprotein Colocalizes with Mitochondria and Induces Mitochondrial Fragmentation in the Late Replication Phase of BKPyV Infection

(A) Z-stacks of RPTECs infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN (top row) or with Dun-agn25D39E (bottom row, large replicating cell next to small non-replicating cell) at 48 hpi, stained for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue). Colocalizing voxels are shown in yellow.

(B) Quantification of mitochondrial morphology in six fields of two independent experiments using Fiji software (mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA).

(C) Z-stacks of BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E-infected cells at 48 hpi, stained for mitochondrial marker Tom20 (red), calreticulin as marker for the ER(magenta), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue). Colocalizing voxels are shown in yellow (scale bar, 5 μm).

(D) Confocal images of RPTECs infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN at indicated times post-infection. Cells were stained for LTag (red), agnoprotein (green), mitochondrial marker Tom20 (cyan), and DNA (blue). White arrows indicate cells magnified (scale bar, 20 μm).

Cells were infected with the indicated viral strains and fixed at 48 hpi as described in Transparent Methods. Z-stacks of BKPyV Dun-AGN, stained for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue). Colocalizing voxels are shown in yellow.

Z-stacks of BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E infected cells, stained for mitochondrial marker Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue). Colocalizing voxels are shown in yellow.

To correlate the severely altered mitochondrial morphology with the viral life cycle, we examined a time course of Dun-AGN infection demonstrating that expression of the early viral LTag at 24 hpi had no effect on the mitochondrial network (Figure 1D). After 36 hpi, expression of the late viral gene region had started and agnoprotein appeared in the cytoplasm, but mitochondrial fragmentation and perinuclear condensation became apparent only from 48 hpi onwards. At 72 hpi, Dun-AGN-replicating cells could be readily identified solely by the dramatically fragmented mitochondrial network using Tom20 staining (Figure 1D). Thus, wild-type and agn25D39E agnoprotein were able to localize to both mitochondria and the ER, which in case of the wild-type Dun-AGN led to mitochondrial fragmentation, whereas this was not observed for the Dun-agn25D39E mutant.

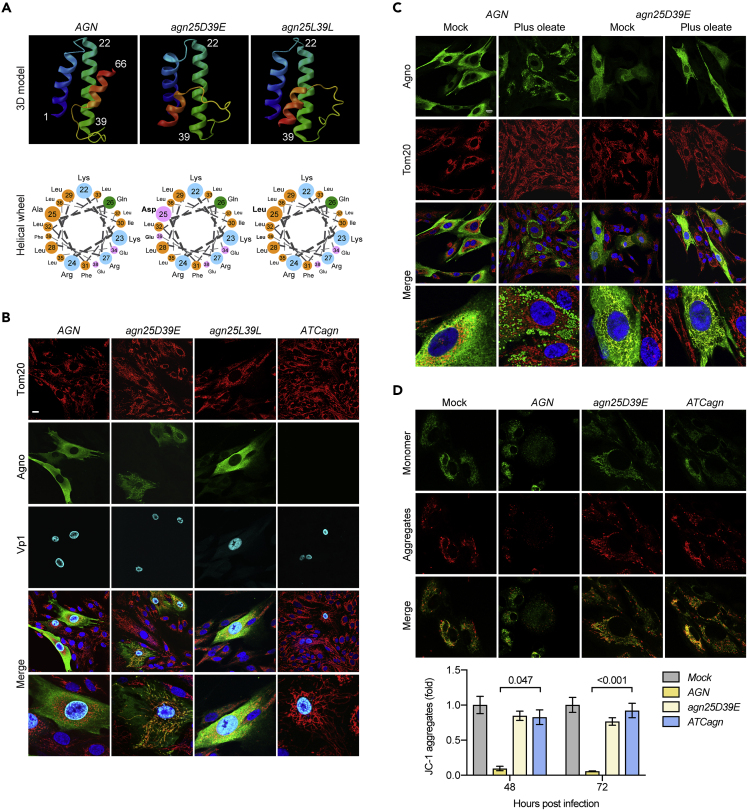

To further characterize the role of agnoprotein and its amphipathic helix in BKPyV replication, two additional isogenic derivatives were generated: Dun-agn25L39L encoding a mutant agnoprotein retaining the amphipathic character of the central α-helix, and Dun-ATCagn, in which the ATG start codon had been changed to ATC to create a “null”-agnoprotein virus. Ribbon models predicted that the overall secondary structures of agn25D39E and agn25L39L were similar to the AGN-encoded wild-type protein in having a short N-terminal and a central helix, whereas the C-terminal structure was not predictable except for a short terminal α-helical tail (Figure 2A). All BKPyV variants were found to proceed to expression of the late viral gene region, as evidenced by nuclear Vp1 staining (Figure 2B). Similar to Dun-AGN wild-type infection, the Dun-agn25L39L-infected RPTECs exhibited a cytoplasmic agnoprotein distribution and mitochondrial fragmentation (Figure 2B). In contrast, Dun-ATCagn-infected RPTECs retained intact mitochondrial networks similar to Dun-agn25D39E but lacked agnoprotein expression as expected (Figure 2B). Because LD-binding had been shown to require the amphipathic character of the central α-helix (Figure 2A) now implicated in mediating mitochondrial fragmentation (Unterstab et al., 2010), the effect of LD-formation on the mitochondrial network was investigated. To this end, RPTECs were infected with Dun-AGN or with Dun-agn25D39E, and 300 μM oleate was added at 24 hpi after early viral gene region expression. Confocal microscopy of Dun-AGN at 48 hpi revealed that agnoprotein was sequestered around LD as described previously, but mitochondrial fragmentation of Dun-AGN infected cells was prevented (Figure 2C). In contrast, Dun-agn25D39E-infected RPTECs retained the mitochondrial colocalization of the mutant agnoprotein without sequestering to LD (Figure 2C, magnification panel bottom right), which in the absence of LD staining are known to appear as punched-out holes (Unterstab et al., 2010). These results linked the amphipathic helix of agnoprotein to LD binding and to mitochondrial fragmentation in a competitive manner.

Figure 2.

The Amphipathic Character of the Central Agnoprotein Helix Is Required for Mitochondrial Fragmentation

(A) Three-dimensional ribbon model of each agnoprotein derivate as predicted with the Quark online algorithm (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) and predicted amphipathic helical wheel of the agnoprotein amino acids 22–39 (http://cti.itc.virginia.edu/∼cmg/Demo/wheel/wheelApp.html).

(B) Confocal images of RPTEC-infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN and isogenic derivatives Dun-agn25D39E, Dun-agn25L39L, and Dun-ATCagn, respectively. Cells were fixed at 48 hpi and stained for mitochondrial marker Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), Vp1 (cyan), and DNA (blue) (scale bar, 20 μm).

(C) Confocal images of RPTECs infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN and BKPyV-Dun-agn25D39E, respectively, at 48 hpi. Cells were mock-treated or treated with 300 μM oleate at 24 hpi (plus oleate). Cells were stained for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue) (scale bar, 20 μm).

(D) Live cell imaging using JC-1 dye (5 μM) of mock-infected or infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN and isogenic derivatives Dun-agn25D39E, Dun-agn25L39L, and Dun-ATCagn, respectively at 48 hpi. Quantification of mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm) by measuring red fluorescent signal (JC-1 aggregates) with the Safire II plate reader of three independent experiments (mean ± SD, Kruskal-Wallis test).

To investigate the functional consequences of agnoprotein expression, we examined the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) using the (Ψm)-dependent accumulation of JC-1 dye, whereby mitochondrial depolarization is indicated by a decrease in the red/green fluorescence intensity. At 48 hpi, Dun-AGN-infected cells exhibited fragmented mitochondria (green channel) and a significant decrease in MMP (red channel), whereas MMP changed little in Dun-agn25D39E- or Dun-ATCagn-infected RPTECs or in mock-treated cells (Figure 2D). Similarly, automated measurements of overall JC-1 red and green signals in cell culture revealed significant MMP decreases of about 40% in Dun-AGN-infected RPTECs at 48 hpi compared with controls. Together, the results indicated that infection with BKPyV expressing an agnoprotein with a central amphipathic helix was necessary for MMP breakdown and network fragmentation in the late viral replication phase.

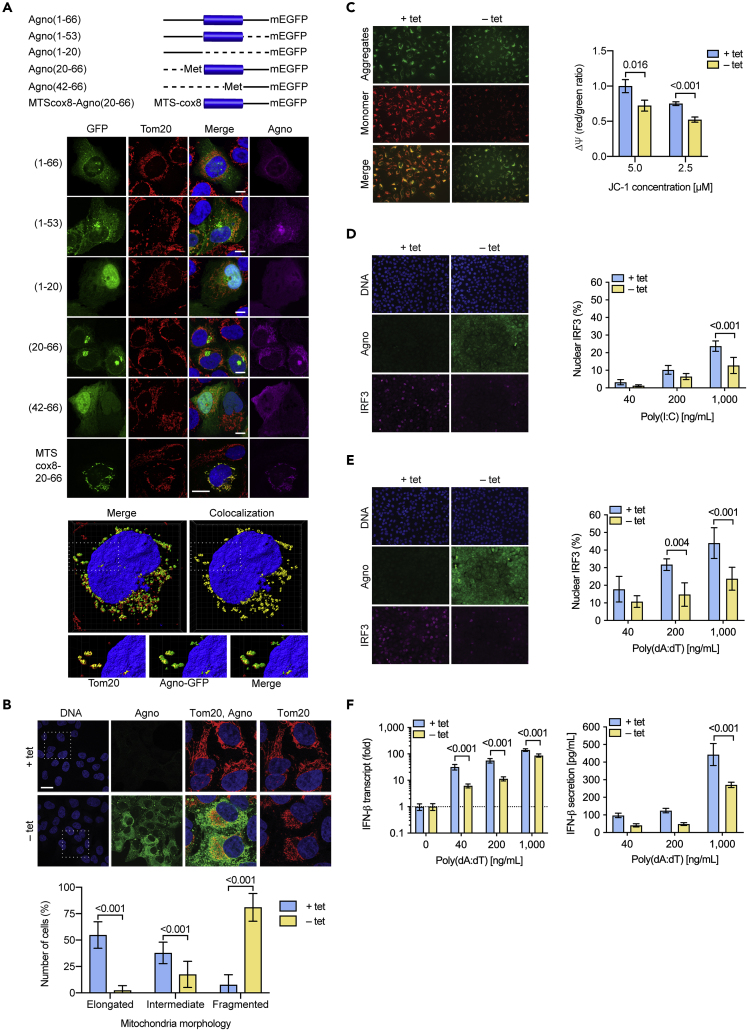

Agnoprotein Is Sufficient for Mitochondrial Fragmentation and Breakdown of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Impairs Innate Immune Signaling

To investigate whether or not agnoprotein expression alone is sufficient for mitochondrial fragmentation, expression vectors containing the full-length gene of wild-type agnoprotein or agnoprotein subdomains fused to monomeric enhanced green fluorescent protein (mEGFP) (Unterstab et al., 2010) were transfected into UTA6 cells (Figure 3A). At 24 h post-transfection (hpt) of the agno(1-66)mEGFP construct, GFP and agnoprotein overlapped in their colocalization to fragmented mitochondria (Figure 3A, top row). Similarly, mitochondrial colocalization and fragmentation was seen for agno(1-53)mEGFP lacking the C-terminal 13 aa of agnoprotein, but not for any of the other truncated agnoprotein constructs shown. Because the truncated agno(20-66)mEGFP had been previously demonstrated to be able to still colocalize with LD (Unterstab et al., 2010), we hypothesized that the N-terminal domain was necessary for mitochondrial targeting in order to mediate the breakdown of the mitochondrial network. Therefore, the N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence of cytochrome c oxidase (MTScox8) was fused to agno(20-66)mEGFP yielding MTScox8-agno(20-66)mEGFP (Figure S1). The results showed that agno(20-66) was sufficient to induce mitochondrial fragmentation if mitochondrial targeting was provided by the MTScox8 sequence (Figure 3A, bottom row and extra panels; Video S3). This was not observed for MTScox8-mEGFP targeting mitochondria but lacking agnoprotein sequences (Figure S3A). To investigate LD binding after addition of oleate, MTScox8-mEGFP and MTScox8-Agno(20-66)mEGFP were transfected and stained for LD using 4,4′-Difluoro-4-bora-(3a,4a)-diaza-s-indacene (bodipy) and Tom70 and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Figures S3B and S3C). The results showed that MTScox8-agno(20-66)mEGFP were co-localizing to LD while MTScox8-mEGFP was not. The data indicated that the amphipathic helix present in the aa20–aa66 of truncated MTScox8-agno(20-66)mEGFP fusion protein was available for interaction with LD, presumably on the surface of mitochondria.

Figure 3.

Agnoprotein Is Sufficient to Mediate Structural and Functional Alterations of Mitochondrial Network

(A) Schematic presentation of agnoprotein-mEGFP fusion constructs transfected into UTA6 cells. Retained aa indicated in parenthesis and presented as solid line, deleted parts presented as dotted line. The central amphipathic helix (aa 22–39) is shown as blue bar. Confocal images of transfected UTA6 cells, transiently expressing the indicated agnoprotein-mEGFP fusion constructs were taken at 24 hpt. Immunofluorescent staining for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (magenta), GFP (green), and DNA (blue) (scale bar, 20 μm).

For MTScox8-agno(20-66), Z-stacks were obtained and colocalizing voxels are shown in yellow.

(B) UTA6-2C9 cells stably transfected with tetracycline (tet)-off inducible BKPyV agnoprotein were cultured for 24 h in the presence (+tet) or absence (−tet) of tetracycline to suppress or induce BKPyV agnoprotein expression, respectively. Confocal images of cells stained for DNA (blue), agnoprotein (green), and Tom20 (red). White rectangle indicating enlarged section. Graph representing corresponding mitochondrial morphology, quantification of six fields using Fiji software of two independent experiments (mean ± SD; two-way ANOVA).

(C) Ψm was assessed by JC-1 dye and imaging of live cells using the signal ratio of aggregate (red)/monomeric (green) normalized to UTA6-2C9 cells not expressing agnoprotein (+tet) versus cells expressing agnoprotein (−tet) using Mithras2 (mean ± SD, unpaired parametric t test).

(D) Nuclear IRF3 translocation following poly(I:C) transfection was compared in UTA6-2C9 cells cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline to suppress or induce BKPyV agnoprotein expression, respectively. Increasing amounts of rhodamine-labeled poly(I:C) was delivered to the cells via lipofection, cells were fixed at 4 hpt, stained for IRF3 (magenta), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue) (left images, 1,000 ng/mL poly(I:C), right panel quantification of nuclear IRF3 of six fields using Fiji software (mean ± SD, Mann-Whitney)).

(E) Nuclear IRF3 translocation following poly(dA:dT) transfection was compared in UTA6-2C9 cells as described in D (left images, 1,000 ng/mL poly(dA:dT), right panel quantification of nuclear IRF3 (mean ± SD, Mann-Whitney)).

(F) Quantification of IFN-β mRNA and IFN-β secretion into cell culture supernatants following poly(dA:dT) stimulation of UTA6-2C9 cells, three experiments (mean ± SD, Mann-Whitney t test).

UTA6 cells transfected with MTScox8-agno(20-66) at 24 hpt. Immunofluorescent staining for Tom20 (red) and agnoprotein-mEGFP (green); DNA (blue). Colocalizing voxels are shown in yellow.

As an independent approach, we examined UTA6-2C9 cells harboring a wild-type full-length agnoprotein under the control of an inducible tetracycline (tet)-off promoter (Cioni et al., 2013). At 24 h in the absence of tet (-tet), agnoprotein was expressed in the cytoplasm and colocalized with fragmented mitochondria, whereas in the presence of tet concentrations suppressing agnoprotein expression (+tet), an intact mitochondrial network was seen (Figure 3B). Importantly, inducing agnoprotein was associated with MMP disruption when examining aggregate (red) and monomeric (green) signals or when using automated JC-1 dye measurements of the cell cultures (Figure 3C).

Because mitochondria play a key role in innate immunity (Koshiba et al., 2011), UTA6-2C9 cells were cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of agnoprotein expression and transfected with either poly(I:C)RNA or poly(dA:dT)DNA, both of which are potent inducers of the type-1 interferon expression via cytoplasmic phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of the interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). At 4 hpt, the effect of agnoprotein expression on the nuclear localization of the IRF3 was examined. The results demonstrated that in the presence of agnoprotein, nuclear IRF3 translocation was significantly reduced after transfecting poly(I:C) (Figure 3D) or poly(dA:dT) (Figure 3E). To functionally relate the agnoprotein-dependent differences in nuclear IRF3 translocation, interferon (IFN)-β expression was quantified after transfection of increasing amounts of poly(dA:dT). The results indicated that agnoprotein expression resulted in a significant reduction of IFN-β transcripts and secreted protein levels (Figure 3F). Together, the data indicated that the expression of BKPyV agnoprotein was necessary and sufficient to induce mitochondrial fragmentation, breakdown of MMP, and impairment of the innate immune sensing of cytosolic DNA and RNA.

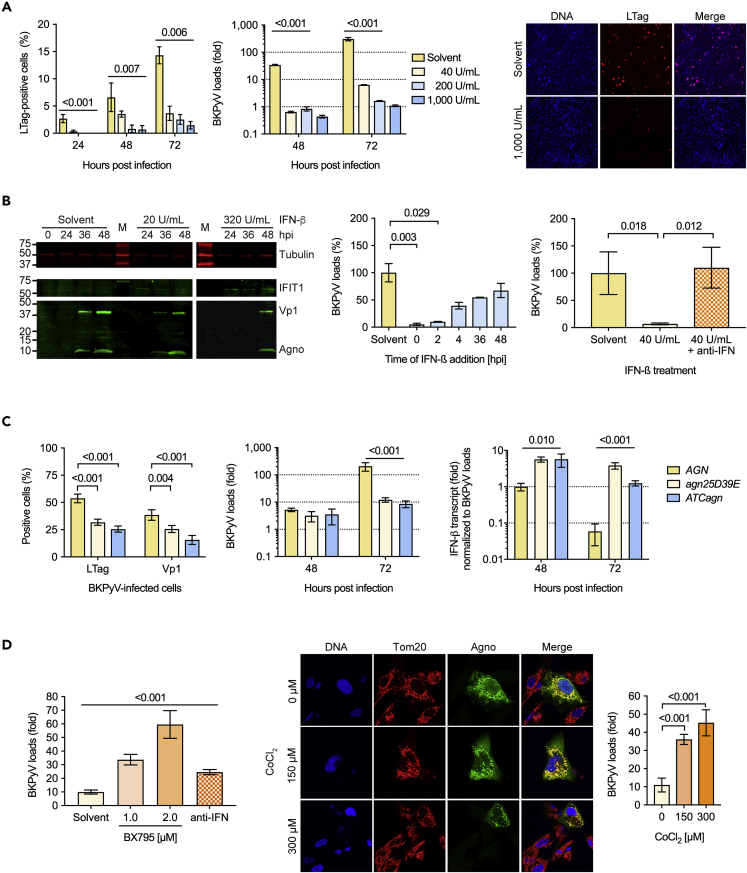

BKPyV Replication Is Inhibited by IFN-β

To determine whether or not BKPyV replication is sensitive to IFN-β, RPTECs were pre-treated, which resulted in an IFN-β dose-dependent reduction of LTag-positive cells and supernatant BKPyV loads at 72 hpi (Figure 4A). SDS/PAGE immunoblot analysis demonstrated an increase of IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats (IFIT) and a reduction of the viral capsid protein Vp1 and agnoprotein (Figure 4B). A time course of IFN-β addition revealed maximal inhibitory effects before or at 2 hpi, but addition at 36 hpi still reduced the supernatant BKPyV loads by 50% (Figure 4B). The reduction in supernatant BKPyV loads could be restored by type-I interferon blockade consisting of a cocktail of blocking antibodies against IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-alpha/beta receptor (Figure 4B). Thus, BKPyV replication in primary human RPTECs was inhibited by IFN-β but could be prevented by anti-IFN-blockade. To examine the role of agnoprotein in BKPyV replication, RPTECs were infected with equivalent infectious doses of Dun-AGN or the mutant derivatives Dun-agn25D39E and Dun-ATCagn. Although the mutant variants replicated, both had lower supernatant BKPyV loads at 72 hpi and a reduced number of LTag- and Vp1-positive cells compared with wild-type virus (Figure 4C). Comparing the IFN-β transcripts at the 48 hpi showed declining levels in the wild-type virus at 72 hpi but significantly higher levels at both time points after Dun-agn25D39E and Dun-ATCagn infection (Figure 4C). Similarly, significantly lower IFN-β transcripts normalized to LTAg transcripts were detected after transfecting RPTECs with the wild-type compared with either of the mutant genomes at 48 hpt and 72 hpt (Figure S4A).

Figure 4.

BKPyV Replication in Primary Human RPTECs Is Sensitive to Type-1 Interferon

(A) RPTECs were treated overnight with the indicated concentrations of IFN-β or solvent. LTag positive cells (left panel; triplicates, mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA) and supernatant BKPyV loads (middle panel; triplicates, mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA) were quantified at the indicated times, and a representative LTag staining of RPTECs at 72 hpi is shown (right panel).

(B) RPTECs were pre-treated with the indicated concentrations of IFN-β and expression of IFIT1 (ISG56), and BKPyV late viral proteins Vp1 and agnoprotein were analyzed at the indicated times post-infection by immunoblot analysis (left panel). RPTECs were treated before or at the indicated times post-infection with 200 U/mL IFN-β, and supernatant BKPyV loads were measured at 72 hpi (middle panel; triplicates, mean ± SD, Kruskal-Wallis test). BKPyV-infected RPTECs were treated with IFN-β in the presence or absence of anti-IFN consisting of antibodies blocking IFN-α, IFN-β, and interferon α/β receptor (right panel), and supernatant BKPyV loads were measured at 72 hpi (right panel; duplicates, mean ± SD, unpaired parametric t test).

(C) RPTECs were infected with the indicated BKPyV variants (MOI = 1 by nuclear LTag staining of RPTCs) and the number of infected cells were quantified by immunofluorescence at 72 hpi (left panel; triplicates, mean ± SD, unpaired parametric t test), and supernatant BKPyV loads were measure at the indicated time post-infection (middle panel; triplicates, mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA). Quantification of IFN-β mRNA in RPTECs infected with the indicated strains was performed at 48 hpi and 72 hpi and normalized to the BKPyV loads (right panel; triplicates, mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA).

(D) RPTECs were infected with BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E, the TBK-1 inhibitor BX795, antibodies blocking IFN-α, IFN-β, and interferon α/β receptor or solvent were added at 36 hpi, and supernatant BKPyV loads were measured at 72 hpi (left panel; triplicates of two independent experiments, mean ± SD, unpaired parametric t test). RPTECs were infected with BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E and treated with the indicated concentrations of CoCl2 or solvent at 24 hpi, and at 72 hpi, confocal microscopy was performed for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green) and DNA (blue), and supernatant BKPyV loads quantified (right panel; triplicates, mean ± SD, unpaired parametric t test).

To investigate whether or not the reduced replication of Dun-agn25D39E could be rescued, the TBK-1-inhibitor (Bx795) to prevent IRF3 phosphorylation or the type-1 interferon-blocking cocktail was added at 36 hpi. The results demonstrated that TBK-1 inhibition or type-1 interferon blockade were able to partially rescue BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E replication (Figure 4C). Under these conditions, there was no effect of TBK-1 inhibition on BKPyV Dun-AGN replication (Figure S4B). Because CoCl2-treatment has been described to induce functional hypoxia by disrupting the MMP (Jung and Kim, 2004), RPTECs were infected with Dun-agn25D39E and treated with 150 μM or 300 μM CoCl2 at 24 hpi. Partial mitochondrial fragmentation of BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E-infected cells was seen together with increased supernatant viral loads at 72 hpi (Figure 4D). Together, the results indicated that the failure of the agn25D39E mutant protein to disrupt the MMP and the mitochondrial network was associated with reduced replication, which could be partially rescued by interfering with innate immune activation, type-1 interferon expression and MMP-dependent mitochondrial signaling relays.

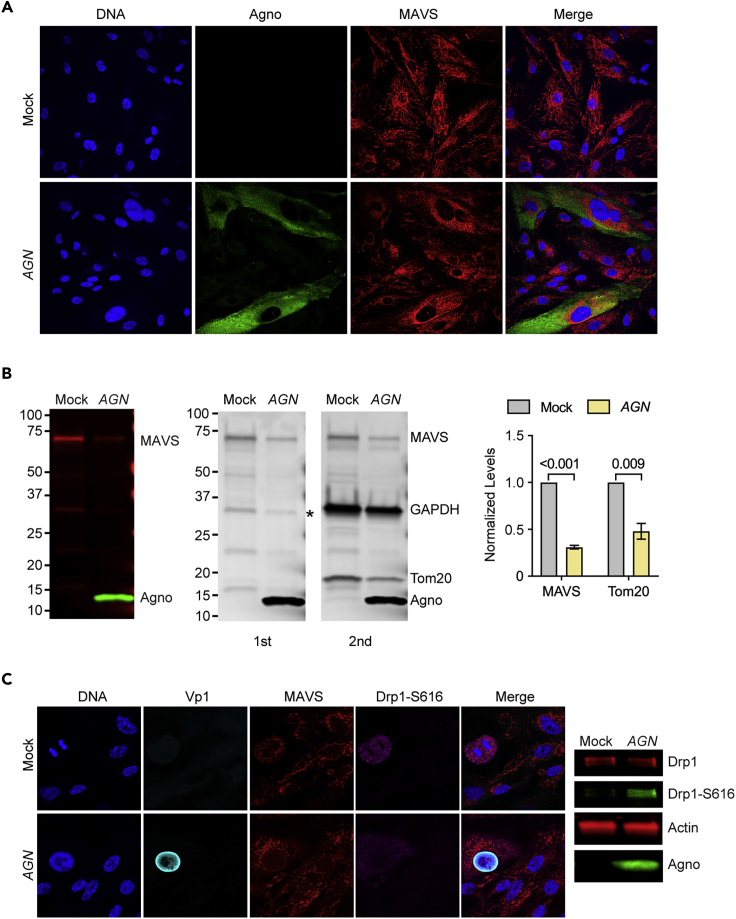

Because MAVS is an important sensor of cytosolic nucleic acids and located on mitochondria, we examined its distribution in Dun-AGN- and mock-infected RPTECs by confocal microscopy. As shown, MAVS colocalized with both intact and agnoprotein-fragmented mitochondria in RPTECs (Figure 5A). Similarly, MAVS also colocalized with fragmented mitochondria in UTA6-2C9 cells following tet-off-induced agnoprotein expression (data not shown). To compare the levels of MAVS in Dun-AGN-infected and mock-treated RPTECs, cell extracts were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting, showing reduced MAVS levels following BKPyV Dun-AGN infection (Figure 5B). Sequential immunoblotting for GAPDH as loading control and for Tom20 revealed a 60%–70% decrease in intensity of the major MAVS band and Tom20 in Dun-AGN-infected RPTECs compared with non-infected control cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

MAVS Colocalizes to Fragmented Mitochondria and Is Decreased in BKPyV-Infected RPTECs

(A) RPTECs were infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN or mock-treated and were either fixed after 72 h for confocal microscopy staining for DNA (blue), agnoprotein (green), and MAVS (red) (top left panel) or were harvested lysing 2.0 × 104 cells per 10 μL Laemmli Sample Buffer and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting for MAVS and agnoprotein (top panels).

(B) The immunoblot (lower panel) stained for MAVS and agnoprotein (first) was subsequently stained for GAPDH and Tom20 (second). MAVS and Tom20 levels were normalized to GAPDH levels as indicated (right panel). GAPDH signal was overlapping with MAVS-specific band (indicated by asterisk) and was subtracted prior normalization.

(C) RPTECs were mock-treated (top panels, left) or infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN bottom panels) and were fixed after 72 h for confocal microscopy for DNA (blue), Vp1 (cyan), MAVS (red), and phosphorylated Drp1-S616 (magenta) (bottom panels, left). Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting using antibodies to total Drp1, phosphorylated Drp1-S616, agnoprotein, and actin (panels, right).

Fragmentation of the mitochondrial network with intact MMP occurs physiologically prior to mitosis and mitochondria partitioning into daughter cells and involves phosphorylation of the dynamin-related protein (Drp)1 at S616 by the cell division kinase CDK1/cyclin B (Figure 5C, mock). In BKPyV Dun-AGN-infected RPTECs, increased Drp1-S616 phosphorylation was detected in Vp1-positive cells but unrelated to mitosis (Figure 5C, AGN). By SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting, Drp1-S616 phosphorylation was increased in Dun-AGN-infected cells compared with mock (Figure 5C, right panel), although overall Drp1 levels were similar (Figure S5A). Comparing isogenic mutant viruses by confocal microscopy revealed that Drp1-S616 phosphorylation was increased in Dun-agn25D39E- and Dun-ATCagn-replicating RPTECs, in which the mitochondrial network remained intact (Figure S5B). The results indicated that increased Drp1-S616 phosphorylation was related to BKPyV infection occurring independent of cell division or expression or functionality of agnoprotein. However, agnoprotein-mediated fragmentation of the mitochondrial network was associated with lowered protein levels of MAVS and Tom20.

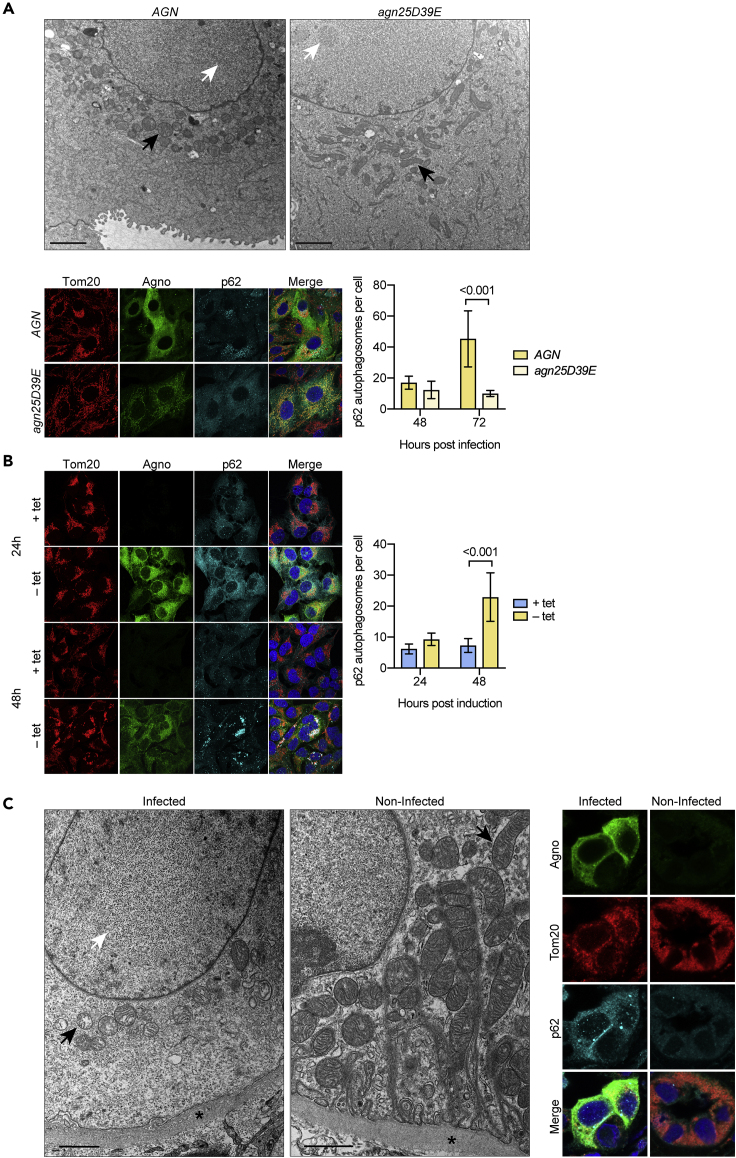

Agnoprotein-Disrupted Mitochondria Are Targeted for p62/SQSTM1 Mitophagy

Given the striking differences in mitochondrial network structure by confocal microscopy, we applied by transmission electron microscopy to examine BKPyV-Dun-AGN- or Dun-agn25D39E-infected RPTECs. At 72 hpi, viral particles in the nucleus served as a marker of the late viral life cycle equivalent to nuclear Vp1 staining in confocal microscopy. In the cytoplasm of Dun-AGN-infected RPTECs, small disrupted mitochondrial vesicles were seen, matching the results obtained by confocal microscopy, as well as several smaller dense multilaminar structures. In contrast, longer filamentous mitochondrial structures were seen in BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E (Figure 6A) in line with tangential cuts of the intact three-dimensional mitochondrial network seen by confocal microscopy (Figure S6). Because damaged mitochondria with MMP breakdown are known to be targeted for autophagy, we investigated p62/SQSTM1 as a marker of mitochondrial autophagosomes (Johansen and Lamark, 2011). At 72 hpi, a significant increase in large confluent p62/SQSTM1-positive signals was observed in Dun-AGN-infected RPTECs compared with the disperse cytoplasmic distribution p62/SQSTM1 in mutant Dun-agn25D39E-infected cells (Figure 6A). Moreover, cytoplasmic aggregates of p62/SQSTM1 colocalizing with Tom20 were prominent in Dun-AGN-infected RPTECs with mitochondrial fragmentation but rare in Dun-agn25D39E-infected cells with intact mitochondrial networks (Figure S6). Similarly, agnoprotein-dependent p62/SQSTM1 aggregates were seen in UTA6-2C9 cells at 24 h post-induction, which condensed at 48 h, indicating that agnoprotein-induced breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential and network was followed by p62/SQSTM1-positive autophagosome formation (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Agnoprotein-Mediated Mitochondrial Fragmentation and p62/SQSTM1-Autophagosomes in Cell Culture and Kidney Transplant Biopsy Tissue

(A) RPTECs were infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN or BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E. At 72 hpi, cells were fixed and processed for TEM (top panels; scale bar, 2 μm) or for confocal microscopy (bottom left panels) staining for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), p62/SQSTM1 (cyan), and DNA (blue). p62/SQSTM1-positive autophagosomes of six fields were quantified using Fiji at 48 hpi and 72 hpi (bottom right panels; mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA).

(B) UTA6-2C9 cells were cultured for 24 h or 48 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline to suppress or induce BKPyV agnoprotein expression, respectively. At the indicated times, confocal microscopy (left panels) was performed after fixing and staining for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), p62/SQSTM1 (cyan), and DNA (blue). p62/SQSTM1-positive autophagosomes were quantified as described in A at 24 h and 48 h (right panels; mean ± SD, two-way ANOVA).

(C) Tissue biopsies from kidney transplant patients with (infected) or without (non-infected) BKPyV-associated nephropathy were studied by transmission electron microscopy (left panels; scale bar, 1 μm) or confocal microscopy (right panels) staining for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), p62/SQSTM1 (cyan), and DNA (blue).

To investigate whether or not similar changes could be observed in BKPyV-associated nephropathy in kidney transplant patients, allograft biopsy samples were analyzed. Indeed, transmission electron microscopy revealed small disrupted mitochondria in the cytoplasm of tubular epithelial cells having viral particles in the nuclei, whereas noninfected tubular epithelial cells showed prominent long mitochondria (Figure 6C). Immunofluorescent staining of kidney allograft biopsies and confocal microscopy for agnoprotein, Tom20, and p62/SQSTM1 revealed fragmented mitochondria and p62/SQSTM1 aggregates in agnoprotein-positive cells in BKPyV-infected parts, which were not seen in non-infected tubular epithelial cells of the same biopsy core (Figure 6C). Together, the data extended the cell culture results to renal allograft nephropathy, showing that BKPyV replication was associated with mitochondrial fragmentation and p62/SQSTM1-positive autophagosome formation in kidney transplant patients.

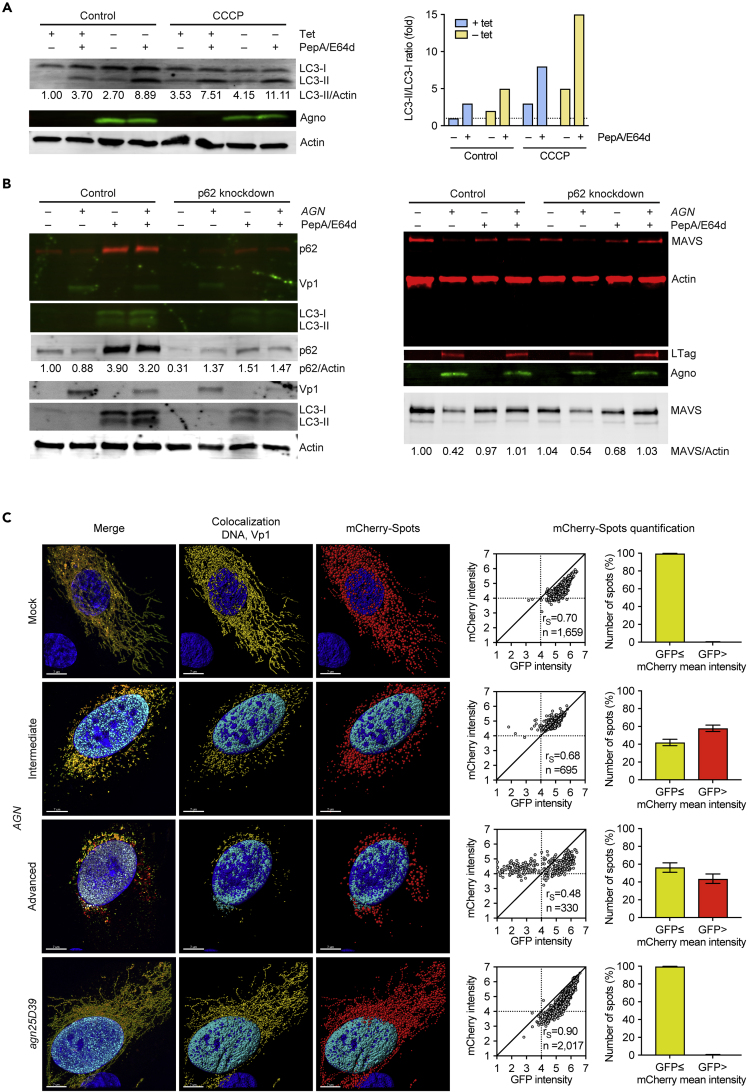

To investigate autophagic flux as a dynamic marker of p62/SQSTM1 mitophagy, the expression levels of LC3-I and its activated lipid-derivative LC3-II were examined in UTA6-2C9 cells by immunoblotting. In untreated cells, mostly LC3-I was detected, but in the presence of the lysosomal protease inhibitor pepstatin-A1/E64d, LC3-I increased and LC3-II became apparent as expected for inhibition of the steady-state autophagic flux (Figure 7A). Following agnoprotein expression, LC3-I and the derivative LC3-II levels were also increased and increased further in the presence of pepstatin-A1/E64d, indicating that agnoprotein expression increased the autophagic flux, which could be partly blocked by lysosomal protease inhibitors (Figure 7A). Treatment with carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) is known to chemically disrupt the MMP and to induce PINK-Parkin-dependent mitophagy (Narendra et al., 2008). Similar to agnoprotein expression, CCCP treatment caused an increase in LC3-I and -II, which further increased in the presence of pepstatin-A1/E64d (Figure 7A). However, agnoprotein expression followed by CCCP treatment did not result in a further increase of LC3-I/II levels but rather increased the relative LC3-II proportion, suggesting that the autophagic flux induced by agnoprotein was further maximized by CCCP treatment. To investigate the role of parkin in this process, UTA6-2C9 cells were transfected with a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-Parkin expression construct and analyzed by confocal microscopy. In YFP-transfected UTA6-2C9 cells not expressing agnoprotein (+tet), little colocalization with fragmented mitochondria was observed. Following the addition of CCCP, extensive cytoplasmic YFP-parkin positive aggregates overlaid Tom20-positive structures in the cytoplasm (Figure S7, +tet, CCCP, magnification). In UTA6-2C9 cells expressing agnoprotein (-tet), the YFP-Parkin signals appeared displaced by agnoprotein from Tom20-colocalizing structures accumulating in the perinuclear cytoplasm (Figure S7, tet-, magnification). Using isosurface rendering to analyze the agnoprotein-induced mitochondrial fragmentation supported the notion that Tom20-positive mitochondrial structures were surrounded by agnoprotein-positive layer, which displaced another layer of YFP-parking (Figure S7, tet-, bottom panels, dashed circle). Together, the data suggested that despite a shared breakdown of the MMP, CCCP- and agnoprotein-induced mitophagy appeared to differ in associating directly and indirectly with Parkin, respectively.

Figure 7.

Agnoprotein Mediates p62/SQSTM1-Dependent Autophagic Flux and Mitophagy

(A) UTA6-2C9 cells were cultured for 48 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline to suppress or induce BKPyV agnoprotein expression, respectively. At 24 h post-induction, pepstatin-A1/E64d (10 μg/mL) and CCCP (10 μM) were added as indicated and cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting as described in Transparent Methods, using RIPA buffer, for LC3-I and II, agnoprotein expression and actin. LC3-II/I ratio were normalized using untreated cells without agnoprotein (+tet) expression as reference.

(B) RPTECs transfected with siRNA-p62 (p62 knockdown) or control were infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN (indicated as AGN). Pepstatin-A1/E64d (10 μg/mL) was added at 48 hpi; when indicated, 2.0 × 104 cells were harvested and lysed per 10 μL Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting as described in Transparent Methods for p62/SQSTM1, BKPyV Vp1, and LC3-I and -II expression (on 0.22 μm PVDF membrane, left panel) or MAVS, actin, BKPyV LTag, and agnoprotein (on 0.45 μm PVDF-FL membrane, right panel).

(C) RPTECs transfected with mCherry-GFP-OMP25TM tandem tag mitophagy reporter were infected with BKPyV Dun-AGN or BKPyV Dun-agn25D39E. At 72 hpi, cells were fixed and stained for Vp1 and DNA. Colocalization of mCherry and GFP (yellow), Vp1 (cyan), and DNA (blue). Z-stacks were acquired and analyzed with IMARIS, and the mCherry signal was transformed into countable spots (according voxel intensity). The GFP and mCherry mean intensity within the spots were quantified (bars represent mean ±95% CI, Wilson/Brown method).

To independently investigate the role of p62/SQSTM1 in autophagic flux following BKPyV infection of RPTECs, LC3 was analyzed in RPTEC with or without siRNA-p62 knockdown. Immunoblotting of the siRNA-p62 knockdown RPTECs revealed a reduction of p62/SQSTM1 levels to approximately 30% of the control RPTECs (Figure 7B, left panel). Upon pepstatin-A1/E64d treatment, p62/SQSTM1 levels as well as the levels of LC3-I and -II increased in the control cells, but not to the same extent in the siRNA-p62 knockdown cells, indicating that the decrease in p62/SQSTM1 levels was associated with lower LC3-II formation and reduced steady-state autophagic flux (Figure 7B, left panel). Following Dun-AGN-infection and pepstatin-A1/E64 treatment, LC3-I and -II levels increased, but the overall levels were lower in the siRNA-p62 knockdown cells, and the LC3-II/-I ratio was decreased as well as the Vp1 levels (Figure 7B, left panel). To investigate the impact of the siRNA-p62 knockdown, whole-cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by SDS/PAGE immunoblotting for MAVS levels in infected and uninfected RPTECs. The results after normalization to actin revealed that MAVS levels were not affected by siRNA-p62 knockdown, but decreased upon BKPyV-AGN-infection, but which could be partly inhibited in the presence of the lysosomal protease inhibitors pepstatin-A1/E64d (Figure 7B, right panel). Together, the data suggested that BKPyV Dun-AGN infection of RPTECs was associated with an increased p62/SQSTM1-dependent autophagic flux, which involved MAVS degradation and which could be reduced by siRNA-p62 knockdown or pepstatin-A1/E64d treatment.

To further investigate mitophagy following BKPyV infection, the tandem tag mitophagy reporter mCherry-mEGFP-OMP25TM carrying the transmembrane domain (TM of OMP25) for targeting to the mitochondrial outer membrane (Bhujabal et al., 2017) was transfected into RPTECs infected with Dun-AGN or Dun-agn25D39E. Quantifying the red and green signals in z-stacks of Vp1-expressing cells following confocal microscopy revealed that the number of mitochondrial signals with mCherry red signals exceeding GFP green signals were higher in Dun-AGN-infected RPTECs and increased as the number of residual mitochondrial fragments progressively decreased in advanced replication phase as compared with Dun-agn25D39E-infected cells or mock-treated controls (Figure 7C). The data indicated that the mitochondrial tandem tag reporter was associated with the mitochondrial network in RPTECs infected with Dun-AGN or Dun-agn25D39E but was progressively disrupted and targeted to the acidic environment of autophagosomes in the former. Together, the data supported the notion that BKPyV Dun-AGN infection of RPTECs was associated with increased mitophagy, which was not observed to this extent for infection with the mutant Dun-agn25D39E.

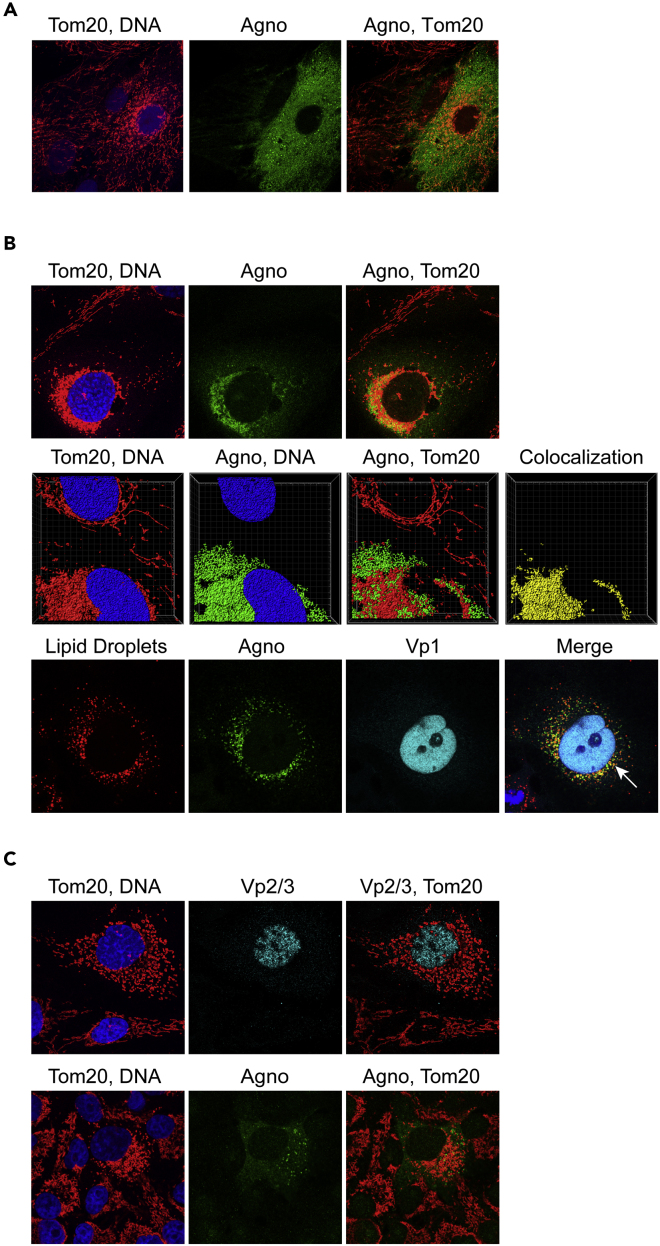

Mitochondrial Colocalization and Fragmentation of Agnoproteins Is Conserved among BKPyV, JCPyV, and SV40

To investigate the impact of agnoprotein expression in another BKPyV strain, infection of RPTECs was studied using a well-characterized, yet slowly replicating BKPyV-WW(1.4) strain carrying an archetype NCCR (Bethge et al., 2015, Gosert et al., 2008). Similar to Dun-AGN, the BKPyV-WW(1.4) strain showed that agnoprotein expression was associated with mitochondrial fragmentation (Figure 8A). Because agnoprotein homologues have been identified in the human polyomavirus JCPyV, we examined SVG-A cells infected with JCPyV-Mad4 strain, for which cytoplasmic agnoprotein expression has been reported previously (Gosert et al., 2010). Colocalization of JCPyV agnoprotein with Tom20 and mitochondrial fragmentation was observed (Figure 8B). Moreover, treatment with oleate and staining with LipidTox revealed colocalization of the JCPyV agnoprotein with LD as has been reported for the BKPyV-encoded agnoprotein (Unterstab et al., 2010).

Figure 8.

Agnoprotein of Archetype BKPyV, JC Polyomavirus, and the Simian SV40 Colocalize to Mitochondria and Disrupt the Mitochondrial Network

(A) RPTECs were infected with BKPyV-WW(1.4) carrying an archetype non-coding control region, and confocal microscopy was performed at 6 dpi after staining for Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue).

(B) SVG-A cells were infected with JCPyV-Mad4, and confocal microscopy was performed at 72 hpi after staining for Tom20 (red), anti-JCPyV agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue) (top panels). Z-stacks of JCPyV-replicating SVG-A cells were acquired, deconvolved, and processed with IMARIS. 3D isosurface renderings of the mitochondrial marker Tom20 (red), agnoprotein (green), and DNA (blue) are shown. Colocalizing voxels are shown in yellow (middle panels). Confocal image of SVG-A cells infected with JCPyV-Mad4, 48 hpi, treated with 300 μM oleate at 24 hpi. Cells were stained for lipid droplets (red), agnoprotein (green), Vp1 (cyan), and DNA (blue). Lipid droplets indicated by white arrow (bottom panels).

(C) CV-1 cells were infected with SV40, and confocal microscopy was performed at 48 hpi after staining for Tom20 (red), Vp2/3 (blue) (top panels), or cross-reacting antisera raised against JCPyV agnoprotein (green) (lower panels).

SV40 infection was studied in CV-1 cells using Vp2/3-expression in the nucleus as a marker of the late viral replication phase (Figure 8C). Because SV40 agnoprotein antibodies were not available, we used the partly cross-reacting antibody raised against the JCPyV agnoprotein together with Tom20 demonstrating fragmentation of the mitochondrial network and colocalization with SV40 agnoprotein (Figure 8C). Together, the data support the view that mitochondrial fragmentation is a conserved feature among different yet related renotropic polyomaviruses found in human and animal species.

Discussion

In the last decade, significant information has been accumulated about how cytoplasmic sensing of viral infections is achieved by the innate immune system (Takeuchi and Akira, 2010, Zevini et al., 2017) and how this crucial first line of defense is subverted to allow for transient or persistent immune escape of acute and chronic viral infections, respectively (Garcia-Sastre, 2017, Goubau et al., 2013). Despite a high infection rate (Virgin et al., 2009) and evidence of immune evasion in the general population (Egli et al., 2009, Kaur et al., 2019), comparatively little is known about relevant mechanisms operating in human polyomaviruses. In this study, we report that the small BKPyV-encoded agnoprotein of 66aa facilitates polyomavirus replication by disrupting the mitochondrial network and its membrane potential during the late phase of the viral replication cycle. Thereby, BKPyV replication is able to evade cytosolic innate immune sensing in this critical stage of viral progeny accumulation, during which DNA damage (Hein et al., 2009) as well as abundant viral DNA genomes and RNA transcripts cumulate in the host cell (Funk et al., 2008, Funk et al., 2006). The precise timing to the critical late viral replication phase (Bernhoff et al., 2008, Low et al., 2004) allows this window of immune evasion to be equally open following de novo cell infection or intracellular reactivation, permitting viral cell-to-cell spread in the renal tubules below the radar of the immune system.

Transfection experiments using the entire agnoprotein or different subdomains fused to the reporter mEGFP as well as the tet-off inducible agnoprotein expression indicate that agnoprotein is necessary and sufficient, using its amino-terminal and central helix for mitochondrial targeting and mitochondrial disruption, respectively. As expected from the key role of mitochondria in relaying innate immune sensing, the agnoprotein-mediated disruption of the MMP was associated with significantly reduced IRF3 translocation into the cell nucleus as well as lowered IFN-β transcript and protein expression following poly(I:C)RNA or poly(dA:dT)DNA stimulation. Importantly, BKPyV viral variants either lacking agnoprotein expression due to a start codon mutation (Dun-ATCagn) or carrying mutations abrogating the amphipathic character of the central helix (Dun-agn25D39E) showed intact mitochondrial networks and little mitophagy but significantly impaired replication compared with the wild-type strain Dun-AGN. The lower replication rate of the mutant Dun-agn25D39E could be partially reversed on three levels of the mitochondrial innate immune relay, namely by CoCl2 treatment affecting the respiratory chain and disrupting the MMP (Jung and Kim, 2004), by BX795 inhibiting the downstream signaling kinase TBK-1, or by type-1 interferon blockade.

Our study also reveals for the first time a critical role of mitophagy in polyomavirus biology. Mitophagy is known to assist in the disposal of irreversibly damaged mitochondria including the irreversible disruption of the MMP as mediated by the wild-type agnoprotein. MAVS remains colocalized to the agnoprotein-mediated mitochondrial fragments targeted for mitophagy leading to significantly lower levels after BKPyV DUN-AGN infection, which could be partially reversed by pepstatin-A1/E64d protease inhibition or by siRNA-knockdown of p62/SQSTM1. Thus, the MMP breakdown and network fragmentation appears to be the immediate key event preventing the activation of the innate immune sensing, to which mitophagy including MAVS or potentially STING degradation follow as common secondary events. The pepstatin-A1/E64d protease inhibition and siRNA knockdown experiments also indicate that agnoprotein increases the p62/SQSTM1-dependent steady-state autophagic flux via LC3-II lipidation in a fashion similar to the one observed following the CCCP-induced mitochondrial membrane potential breakdown (Johansen and Lamark, 2011). Although CCCP-induced mitophagy has been reported to directly involve the PINK-Parkin pathway (Bhujabal et al., 2017), our results indicate that mitophagy by agnoprotein involves shifting Parkin by an agnoprotein layer away from the fragmented mitochondria. Confocal microscopy and comparison of LCI/II levels indicate that mitophagy by agnoprotein can be further increased by CCCP. Together, this suggests that the agnoprotein-mediated mitophagy appears to differ from the direct CCCP-induced Parkin-involving process. Further evidence for increased autophagic flux was obtained using the tandem tag mitophagy reporter mCherry-mEGFP-OMP25TM revealing acidification in mitophagosomes of BKPyV-AGN-infected RPTECs, which was not observed to the same extent in agn25D39E-mutant-infected RPTECs. Notably, pepstatin-A1/E64d protease inhibition and p62-siRNA knockdown were associated with the reduced Vp1-protein levels in BKPyV Dun-AGN-infected primary human RPTECs. This observation suggests that the autophagic flux may be relevant for the effective biosynthesis in the exhaustive late viral replication phase following the functional and structural loss of the mitochondrial power plants (Forbes, 2016). However, the precise adaptor proteins and pathways need further study (Farre and Subramani, 2016).

Innate immune sensors have been characterized in primary human RPTECs and in kidney biopsies by transcriptional profiling identifying antiviral, proinflammatory, and proapoptotic responses (Heutinck et al., 2012, Ribeiro et al., 2012). Other studies reported that BKPyV infection of RPTECs can occur without inducing innate immune sensors by as yet unknown mechanisms (Abend et al., 2010, An et al., 2019, de Kort et al., 2017). However, these studies failed to reveal inhibition of BKPyV replication by type-1 interferons, which is in contrast to our results for BKPyV shown here and those recently reported for JCPyV (Assetta et al., 2016). We show that wild-type BKPyV is susceptible to IFN-β, an effect that can be blocked by type-I interferon blockade. Conversely, the IFN-β transcript levels were higher in both agn25D39E and ATCagn mutants compared with the wild-type Dun-AGN virus. Indeed, type-I interferon blockade and the TBK-1 inhibition partially reversed the reduced replication of the mutant Dun-agn25D39E virus in line with a higher basal IFN-β transcript expression in the agnomutant compared with wild-type virus, whereas TBK-1 inhibition has no effect on the wild-type BKPyV-Dun replication.

Importantly, confocal and transmission electron microscopy studies of biopsies obtained from kidney transplant patients provide independent evidence of mitochondrial fragmentation and p62/SQSTM1 mitophagy in vivo. These data suggest that the combined effects of immune escape, mitophagy, and viral spread are operating not only in a relevant primary human cell culture model of RPTECs but also in one of the currently most challenging pathologies affecting kidney transplantation (Ramos et al., 2009). Intriguingly, the BKPyV-agnoprotein-induced immune subversion and p62/SQSTM1 mitophagy may explain the earlier reported paradox of abundant detection of agnoprotein in vivo and the low agnoprotein-specific antibody and T cell response (Leuenberger et al., 2007) and provide a new twist to BKPyV-promoting hypoxic mechanisms following renal ischemia/reperfusion injury (Atencio et al., 1993, Fishman, 2002, Hirsch et al., 2006).

Our results also shed new light on previous reports on BKPyV agnoprotein and the closely related JCPyV and SV40 homologues (Gerits and Moens, 2012, Saribas et al., 2019): These include facilitating polyomavirus replication (Ng et al., 1985), increasing viral late-phase production (Carswell et al., 1986) and plaques size (Hou-Jong et al., 1987), acting as viroporin (Suzuki et al., 2010) or egress factor (Panou et al., 2018) from the nucleus, by disrupting the tight surrounding mitochondrial network. We demonstrate that mitochondrial fragmentation occurs not only for BKPyV strains carrying an archetype NCCR but also for the human JCPyV or the monkey SV40, suggesting that this dramatic agnoprotein-mediated function is evolutionary conserved and active across different species, cell types, and hosts. In line with this notion, we were unable to identify relevant point mutations in the critical amphipathic wheel of agnoprotein among more than 300 whole genome sequences available in the GenBank (unpublished data) (Leuzinger et al., 2019). Thus, we conclude that the small agnoprotein of less than 66 aa facilitates BKPyV replication by an effective mechanism also seen in other renotropic human and animal polyomaviruses, which is unmatched in other DNA viruses through its dramatic simplicity (Koshiba et al., 2011).

Indeed, rather complex viral mechanisms have been described targeting the cytosolic sensing platforms at steps up- and downstream of mitochondria and associated ER membranes (Khan et al., 2015). Thus, the matrix protein (M-protein) of parainfluenza-3 has been reported to translocate to mitochondria, where it induces mitophagy via LC3-II in a PINK/Parkin-independent manner (Ding et al., 2017). However, the M-protein is a structural protein and according to the current model acts early following entry into host cells and requires piggy-back import via the mitochondrial elongation factor TUFM (Ding et al., 2017), whereas our study indicates that the non-structural BKPyV agnoprotein targets mitochondria directly during the late replication phase. Unlike BKPyV, HCV and other (+)-ssRNA viruses replicating in the cytoplasm appear to induce mitochondrial fragmentation and mitophagy in a PINK-Parkin-dependent fashion (Gou et al., 2017). Although structurally unrelated to agnoprotein, the 247aa-long cytomegalovirus (CMV) US9 glycoprotein appears to suppress both MAVS and STING pathways, TBK-1 activation, and IFN-β expression by disrupting the mitochondrial membrane potential in the late CMV replication phase (Choi et al., 2018, Mandic et al., 2009). Given the association of agnoprotein with LD, we were intrigued by the similarity to the antiviral host cell protein viperin, which is expressed following RNA and DNA virus infections (Gizzi et al., 2018, Hee and Cresswell, 2017). The antiviral effects of viperin have been attributed to a perplexing variety of functions including interference with lipid metabolism and formation of detergent-resistant lipid rafts at the sites of influenza budding (Wang et al., 2007). Similar to agnoprotein, viperin contains an amphipathic helix required for adsorbing to the cytosolic face of LD and ER membranes (Hinson and Cresswell, 2009a, Hinson and Cresswell, 2009b). However, viperin may facilitate viral replication (Hee and Cresswell, 2017), when re-directed to mitochondria by the CMV-encoded Bax-specific inhibitor viral mitochondria-localized inhibitor of apoptosis (vMIA) carrying a mitochondrial targeting domain (Cam et al., 2010, Seo et al., 2011). Thus, the hijacked viperin-CMV-vMIA complex shares properties accommodated in only 66aa of BKPyV agnoprotein.

Limitations of the Study

We cannot exclude a more direct role of agnoprotein on STING signaling through MMP breakdown or through its ER colocalization. Current concepts suggest that BKPyV as a DNA virus would be expected to preferentially be sensed via cGAS/STING according. However, increasing data indicate a close interaction between DNA- and RNA-sensing pathway coupling MAVS and STING activation on mitochondria and ER to TBK-1 activation downstream including through RNA-polymerase III transcription of cytoplasmic DNA-fragments (Chiu et al., 2009, Zevini et al., 2017). Our results demonstrate that agnoprotein expression alone is sufficient to inhibit innate immune responses to both poly(I:C)-RNA and poly(dA:dT)-DNA.

Even though our study indicates that agnoprotein is both necessary and sufficient for MMP breakdown and mitochondrial fragmentation, it is presently unclear, whether or not this is achieved by the direct interaction with cellular proteins other than the mitochondrial import machinery. Experimental MMP breakdown by CCCP has been shown to also suppress STING signaling, further merging the cytosolic RNA- and DNA-triggered responses (Kwon et al., 2017). Finally, details of the mitophagy process, the role of the involved proteins, and their direct or indirect interaction require further study.

Given the abundance of BKPyV agnoprotein in the cytoplasm and the clearly distinct colocalization patterns to ER in addition to mitochondria, further studies need to be carefully conducted in order to avoid misleading artifacts. For the Bcl-2 family of proteins, a hierarchy of interactome complexes has emerged over the last decade (Bleicken et al., 2017, Edlich et al., 2011). Moreover, for the related JCPyV agnoprotein, a strong tendency to form multimeric aggregates in vitro has been reported (Sami Saribas et al., 2013), which undoubtedly reduces the specificity of otherwise straight-forward pull-down approaches and complicates potential functional attributions. This notion has been recently confirmed by a detailed study of potential proteomic interaction partners for the homologous JCPyV agnoprotein (Saribas et al., 2019). Presently, we favor a minimal model (Figure 9) in which mitochondrial targeting of N-terminal domain of agnoprotein allows for embedding the central amphipathic helix into the outer leaflet of the outer mitochondrial membrane similar to other amphipathic proteins, where it remains available for LD-binding. Indirect support comes from the recruitment of LD to the MTScox8-agno(20-66)mEGFP not observed for MTScox8-mEGFP following transfection and oleate treatment. However, further studies are needed to investigate whether or not this simple plug-and-play suffices to progressively leaking protons and causing the loss of membrane potential, preventing TBK-1 activation, and targeting for p62/SQSTM1 mitophagy (Jarsch et al., 2016, McMahon and Gallop, 2005, Shen et al., 2012).

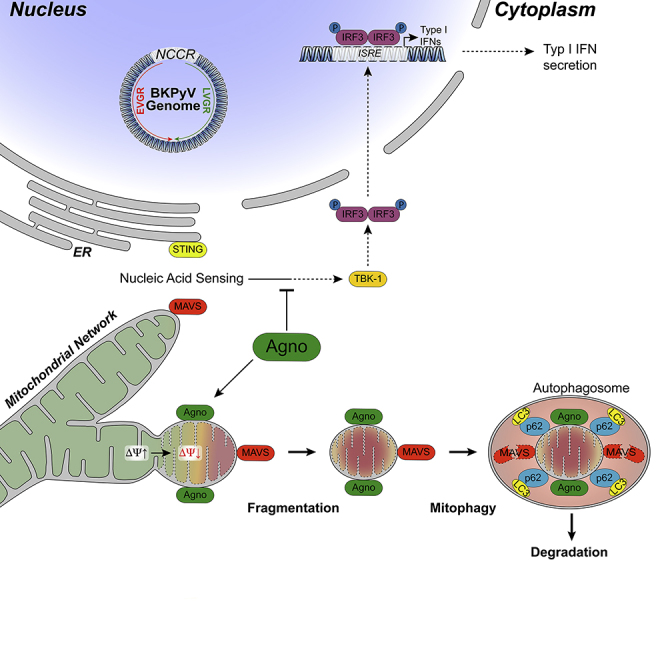

Figure 9.

Working Model of BKPyV Agnoprotein Mediating Innate Immune Evasion by Mitochondrial Membrane Breakdown, Network Fragmentation, and Mitophagy.

In summary, our study provides important novel perspectives into how BKPyV replication is effectively facilitated in the critical late phase of the viral life cycle by the small accessory agnoprotein in at least three complementary ways: (1) inactivating immune sensing and the inhibitory effects of interferon-β expression by breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential; (2) enhancing the supply of biosynthetic building blocks via increased autophagic flux, and (3) facilitating viral release of nuclear virions by fragmenting the nucleus-surrounding mitochondrial network. Finally, our observations suggest that BKPyV agnoprotein is not only important for immune escape and urinary shedding in healthy immunocompetent hosts but may also facilitate the rapid cell-to-cell spread inside the renal tubules, and hence the progression to BKPyV nephropathy in kidney transplant patients. These insights may help to design novel antiviral and immunization strategies and permit identifying novel markers readily distinguishing BKPyV nephropathy from allograft rejection (Hirsch and Randhawa, 2019).

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Hans H. Hirsch, M.D., M.Sc (hans.hirsch@unibas.ch).

Materials Availability

-

•

Recombinant virus derivatives of the BKPyV Dunlop strain generated in this study will be made available on request, but we may require a payment and/or a completed Materials Transfer Agreement if there is potential for commercial application.

-

•

All other unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pascal Lorentz of the confocal imaging core facility of the Department Biomedicine, University of Basel and Mohamed Chami at the electron microscopy core facility of the Biocenter, University of Basel for advice and support with the imaging studies. We are grateful to Professor Terje Johansen, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway for helpful discussions and for providing the tandem tag mitophagy reporter construct mCherry-mEGFP-OMP25TM. We are indebted to Ms Erika Hofmann for the timely updates of the reference library. This study was funded by an appointment grant of the University of Basel to H.H.H.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.M. and H.H.H.; Methodology: J.M., F.H.W., F.E.G., G.U., M.W., C.H.R., and C.B.D.; Validation: J.M., F.H.W., G.U., F.E.G., M.W., C.H.R., C.B.D., and H.H.H.; Investigation: J.M., F.H.W., F.E.G., G.U., C.H.R., C.B.D., and H.H.H.; Data Curation: J.M., F.H.W., and H.H.H.; Writing—Original Draft: J.M. and H.H.H.; Writing—Review & Editing: J.M., F.H.W., F.E.G., G.U., C.H.R., C.B.D., H.H., and H.H.H.; Visualization: J.M., F.H.W., and H.H.H.; Resources: J.M., F.H.W., G.U., C.H.R., and C.B.D.; Data Curation: J.M., F.H.W., and H.H.H.; Supervision: H.H.H.; Project Administration: H.H.H.; Funding Acquisition: H.H.H.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101257.

Supplemental Information

References

- Abend J.R., Low J.A., Imperiale M.J. Global effects of BKV infection on gene expression in human primary kidney epithelial cells. Virology. 2010;397:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An P., Saenz Robles M.T., Duray A.M., Cantalupo P.G., Pipas J.M. Human polyomavirus BKV infection of endothelial cells results in interferon pathway induction and persistence. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007505. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assetta B., De Cecco M., O'Hara B., Atwood W.J. JC polyomavirus infection of primary human renal epithelial cells is controlled by a type I IFN-induced response. mBio. 2016;7:e00903–e00916. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00903-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atencio I.A., Shadan F.F., Zhou X.J., Vaziri N.D., Villarreal L.P. Adult mouse kidneys become permissive to acute polyomavirus infection and reactivate persistent infections in response to cellular damage and regeneration. J. Virol. 1993;67:1424–1432. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1424-1432.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhoff E., Gutteberg T.J., Sandvik K., Hirsch H.H., Rinaldo C.H. Cidofovir inhibits polyomavirus BK replication in human renal tubular cells downstream of viral early gene expression. Am. J. Transplant. 2008;8:1413–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethge T., Hachemi H.A., Manzetti J., Gosert R., Schaffner W., Hirsch H.H. Sp1 sites in the noncoding control region of BK polyomavirus are key regulators of bidirectional viral early and late gene expression. J. Virol. 2015;89:3396–3411. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03625-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhujabal Z., Birgisdottir A.B., Sjottem E., Brenne H.B., Overvatn A., Habisov S., Kirkin V., Lamark T., Johansen T. FKBP8 recruits LC3A to mediate Parkin-independent mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:947–961. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binggeli S., Egli A., Schaub S., Binet I., Mayr M., Steiger J., Hirsch H.H. Polyomavirus BK-specific cellular immune response to VP1 and large T-antigen in kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2007;7:1131–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleicken S., Hantusch A., Das K.K., Frickey T., Garcia-Saez A.J. Quantitative interactome of a membrane Bcl-2 network identifies a hierarchy of complexes for apoptosis regulation. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:73. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cam M., Handke W., Picard-Maureau M., Brune W. Cytomegaloviruses inhibit Bak- and Bax-mediated apoptosis with two separate viral proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:655–665. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carswell S., Resnick J., Alwine J.C. Construction and characterization of CV-1P cell lines which constitutively express the simian virus 40 agnoprotein: alteration of plaquing phenotype of viral agnogene mutants. J. Virol. 1986;60:415–422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.415-422.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesaro S., Dalianis T., Hanssen Rinaldo C., Koskenvuo M., Pegoraro A., Einsele H., Cordonnier C., Hirsch H.H., Group E.-. ECIL guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of BK polyomavirus-associated haemorrhagic cystitis in haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:12–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Trofe J., Gordon J., Autissier P., Woodle E.S., Koralnik I.J. BKV and JCV large T antigen-specific CD8(+) T cell response in HLA A∗0201(+) kidney transplant recipients with polyomavirus nephropathy and patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J. Clin. Virol. 2008;42:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y.H., Macmillan J.B., Chen Z.J. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell. 2009;138:576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.J., Park A., Kang S., Lee E., Lee T.A., Ra E.A., Lee J., Lee S., Park B. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded US9 targets MAVS and STING signaling to evade type I interferon immune responses. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:125. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02624-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioni M., Leboeuf C., Comoli P., Ginevri F., Hirsch H.H. Characterization of immunodominant BK polyomavirus 9mer epitope T cell responses. Am. J. Transplant. 2016;16:1193–1206. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioni M., Mittelholzer C., Wernli M., Hirsch H.H. Comparing effects of BK virus agnoprotein and herpes simplex-1 ICP47 on MHC-I and MHC-II expression. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013;2013:626823. doi: 10.1155/2013/626823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCaprio J.A., Imperiale M.I., Major E.O. Polyomaviruses. In: David M., Knipe P.H., editors. Fields Virology. 6th Edition. Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Vol. 2: 2013. pp. 1633–1661. Chapter 53. [Google Scholar]

- de Kort H., Heutinck K.M., Ruben J.M., Ede V.S.A., Wolthers K.C., Hamann J., Ten Berge I.J.M. Primary human renal-derived tubular epithelial cells fail to recognize and suppress BK virus infection. Transplantation. 2017;101:1820–1829. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B., Zhang L., Li Z., Zhong Y., Tang Q., Qin Y., Chen M. The matrix protein of human parainfluenza virus type 3 induces mitophagy that suppresses interferon responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:538–547.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlich F., Banerjee S., Suzuki M., Cleland M.M., Arnoult D., Wang C., Neutzner A., Tjandra N., Youle R.J. Bcl-x(L) retrotranslocates Bax from the mitochondria into the cytosol. Cell. 2011;145:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli A., Infanti L., Dumoulin A., Buser A., Samaridis J., Stebler C., Gosert R., Hirsch H.H. Prevalence of polyomavirus BK and JC infection and replication in 400 healthy blood donors. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;199:837–846. doi: 10.1086/597126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre J.C., Subramani S. Mechanistic insights into selective autophagy pathways: lessons from yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:537–552. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman J.A. BK virus nephropathy--polyomavirus adding insult to injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:527–530. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes J.M. Mitochondria-power players in kidney function? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;27:441–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk G.A., Gosert R., Comoli P., Ginevri F., Hirsch H.H. Polyomavirus BK replication dynamics in vivo and in silico to predict cytopathology and viral clearance in kidney transplants. Am. J. Transplant. 2008;8:2368–2377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk G.A., Steiger J., Hirsch H.H. Rapid dynamics of polyomavirus type BK in renal transplant recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;193:80–87. doi: 10.1086/498530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Sastre A. Ten strategies of interferon evasion by viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerits N., Moens U. Agnoprotein of mammalian polyomaviruses. Virology. 2012;432:316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizzi A.S., Grove T.L., Arnold J.J., Jose J., Jangra R.K., Garforth S.J., Du Q., Cahill S.M., Dulyaninova N.G., Love J.D. A naturally occurring antiviral ribonucleotide encoded by the human genome. Nature. 2018;558:610–614. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosert R., Kardas P., Major E.O., Hirsch H.H. Rearranged JC virus noncoding control regions found in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy patient samples increase virus early gene expression and replication rate. J. Virol. 2010;84:10448–10456. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00614-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosert R., Rinaldo C.H., Funk G.A., Egli A., Ramos E., Drachenberg C.B., Hirsch H.H. Polyomavirus BK with rearranged noncoding control region emerge in vivo in renal transplant patients and increase viral replication and cytopathology. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:841–852. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou H., Zhao M., Xu H., Yuan J., He W., Zhu M., Ding H., Yi L., Chen J. CSFV induced mitochondrial fission and mitophagy to inhibit apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39382–39400. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubau D., Deddouche S., Reis e Sousa C. Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity. 2013;38:855–869. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf F.E., Hirsch H.H. BK polyomavirus after solid organ and hematopoietic cell transplantation: one virus – three diseases. In: Morris M.I., Kotton C.N., Wolfe C., editors. Emerging Transplant Infections. Springer Nature; 2020. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee J.E., Hirsch H.H. Polyomaviruses. In: Richman D., Whitley R., Hayden F., editors. Clinical Virology. Fourth Edition. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2017. pp. 599–623.asmscience.org Chapter 28. [Google Scholar]

- Hartlova A., Erttmann S.F., Raffi F.A., Schmalz A.M., Resch U., Anugula S., Lienenklaus S., Nilsson L.M., Kroger A., Nilsson J.A. DNA damage primes the type I interferon system via the cytosolic DNA sensor STING to promote anti-microbial innate immunity. Immunity. 2015;42:332–343. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hee J.S., Cresswell P. Viperin interaction with mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) limits viperin-mediated inhibition of the interferon response in macrophages. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein J., Boichuk S., Wu J., Cheng Y., Freire R., Jat P.S., Roberts T.M., Gjoerup O.V. Simian virus 40 large T antigen disrupts genome integrity and activates a DNA damage response via Bub1 binding. J. Virol. 2009;83:117–127. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01515-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heutinck K.M., Rowshani A.T., Kassies J., Claessen N., van Donselaar-van der Pant K.A., Bemelman F.J., Eldering E., van Lier R.A., Florquin S., Ten Berge I.J. Viral double-stranded RNA sensors induce antiviral, pro-inflammatory, and pro-apoptotic responses in human renal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2012;82:664–675. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson E.R., Cresswell P. The antiviral protein, viperin, localizes to lipid droplets via its N-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:20452–20457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911679106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson E.R., Cresswell P. The N-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix of viperin mediates localization to the cytosolic face of the endoplasmic reticulum and inhibits protein secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4705–4712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807261200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch H.H. Spatio-temporal virus surveillance for severe acute respiratory infections in resource-limited settings: how deep need we go? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019;68:1126–1128. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch H.H., Drachenberg C.B., Steiger J., Ramos E. Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy in renal transplantation: critical issues of screening and management. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;577:160–173. doi: 10.1007/0-387-32957-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch H.H., Randhawa P.S. BK polyomavirus in solid organ transplantation-Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019;33:e13528. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch H.H., Yakhontova K., Lu M., Manzetti J. BK polyomavirus replication in renal tubular epithelial cells is inhibited by sirolimus, but activated by tacrolimus through a pathway involving FKBP-12. Am. J. Transplant. 2016;16:821–832. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou-Jong M.H., Larsen S.H., Roman A. Role of the agnoprotein in regulation of simian virus 40 replication and maturation pathways. J. Virol. 1987;61:937–939. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.3.937-939.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperiale M.J., Jiang M. Polyomavirus persistence. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016;3:517–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A., Medzhitov R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science. 2010;327:291–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1183021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarsch I.K., Daste F., Gallop J.L. Membrane curvature in cell biology: an integration of molecular mechanisms. J. Cell Biol. 2016;214:375–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201604003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen T., Lamark T. Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy. 2011;7:279–296. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J.Y., Kim W.J. Involvement of mitochondrial- and Fas-mediated dual mechanism in CoCl2-induced apoptosis of rat PC12 cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;371:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur A., Wilhelm M., Wilk S., Hirsch H.H. BK polyomavirus-specific antibody and T-cell responses in kidney transplantation: update. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2019;32:575–583. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M., Syed G.H., Kim S.J., Siddiqui A. Mitochondrial dynamics and viral infections: a close nexus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1853:2822–2833. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge S.F., Sauter D., Kirchhoff F. SnapShot: antiviral restriction factors. Cell. 2015;163:774–774.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba T., Yasukawa K., Yanagi Y., Kawabata S. Mitochondrial membrane potential is required for MAVS-mediated antiviral signaling. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:ra7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]