Abstract

Objective:

Although use of telemedicine for the treatment of opioid use disorders (Tele-OUD) is growing, there is limited research on how it is actually being deployed in treatment. We explored how health centers across the U.S. are using tele-OUD in treatment as well as reasons for nonadoption.

Methods:

We used the 2018 SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator database and literature review to create a sample of community mental health centers and federally qualified health centers with telemental health services. From this list of health centers, we ued maximum diversity sampling to identify and recruit health center leaders to participate in semistructured interviews. We used inductive and deductive approaches to develop site summaries.

Results:

Twenty-two health centers from 14 different states participated. Of these, 8 offered tele-OUD. Among centers with tele-OUD, medication management was the most common service provided via video. Typically, health centers offered telemedicine visits after an initial, in-person visit with a waivered (prescribing) provider. Some programs only offered counseling via telemedicine. Leading barriers to treatment that tele-OUD program representatives mentioned included regulations on the prescribing of controlled substances, including buprenorphine, and difficulties in sending lab results to distant (prescribing) providers. Nonadopters reported not offering tele-OUD due to regulations in controlled substance prescribing, complexities and regulatory barriers to offering group visits, and the belief that in-person OUD services were meeting patient need.

Conclusions:

Tele-OUD is being deployed in a variety of ways. Describing current delivery models can inform strategies to promote and implement tele-OUD to combat the opioid epidemic.

Keywords: Telehealth, Telemedicine, Opioid use disorder, Substance use disorder, Telemental health, Tele-SUD, Tele-OUD

1. Introduction

Connecting individuals with opioid use disorders (OUD) to evidence-based treatment, including OUD medications, counseling, and psychotherapy, is a key challenge in combating the opioid epidemic (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2015). Only about 20% of individuals with OUD receive treatment (Saloner & Karthikeyan, 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016) due to barriers such as limits on insurance coverage, lack of waivered providers who can prescribe OUD medications, concerns about privacy, and stigma (Rapp et al., 2006).

Telemedicine, in the form of live videoconferencing with a clinician, is one solution to improve access to care for OUD that numerous government agencies and professional organizations have endorsed (The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, 2017; Association for Behavioral Health and Wellness, 2016; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015; Liebelt et al., 2017; National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2018). Recent policy changes such as the 2018 SUPPORT Act have reduced barriers to delivering telemedicine for substance use disorder services more broadly, allowing Medicare patients with substance use disorders to receive services from any location, including at home, and directs the attorney general to issue final regulations for a special registration that could allow telemedicine providers to prescribe controlled substances such as buprenorphine without an in-person exam.

Although barriers to tele-OUD are eroding and use is growing rapidly (Huskamp et al., 2018), little is known about how it is being deployed in OUD treatment (e.g., for psychotherapy, for management of OUD medications). Most of literature on tele-OUD implementation to date has focused on experiences with tele-OUD within the context of an individual telemedicine program or within one state (Lauckner & Whitten, 2016; Molfenter et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2019; Center for Connected Health Policy, 2018). We aimed to explore how federally qualified health centers (FQHC) and community mental health centers (CMHC) across the U.S. are using tele-OUD services as well as reasons for nonadoption to inform strategies to promote and implement tele-OUD to combat the opioid epidemic.

2. Materials and methods

We assembled a purposive sample of health centers with telemedicine capabilities representing both tele-OUD adopters and nonadopters by 1) reviewing grey and published literature describing health centers with active tele-OUD programs and 2) searching the 2018 SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator database (https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/) for health centers that reported having telemedicine capabilities. We focused on FQHCs and CMHCs because of their focus on underserved populations.

We invited all health centers that we could identify with active tele-OUD programs and used maximum diversity sampling to select additional health centers that reported having active telemedicine programs, but where use of tele-OUD was not known a priori. We sought to obtain variation on tele-OUD adoption, health center type, rural vs. urban location, and U.S. region. We invited health center chief executive officers and behavioral health department leaders to participate in a 60-minute telephone interview. Sixty-two percent of contacted health centers agreed to participate. From February to June 2019, we completed a total of 22 semistructured interviews with representatives from CMHCs (n=11) and FQHCs (n=11).

Interviews followed a semistructured protocol, and we recorded and transcribed them. The interview protocol included open-ended questions on the characteristics of telemental health and tele-OUD programs, use of tele-OUD in conjunction with in-person care, barriers to tele-OUD services, and reasons for nonuse of tele-OUD (among nonadopters). We also included probes to further explore emerging themes. Harvard University’s institutional review board approved this study. Interview transcripts were uploaded into Dedoose (Dedoose, 2019), a cloud-based qualitative analysis program. We employed an inductive and deductive approach (which identified codes mapped to key research questions covered within the interview protocol as well as novel topics that emerged) to develop a templated site summary for each health center. The lead author developed the first site summary and conducted a coding training for two additional team members involved in coding. Following training, each team member was assigned an additional 5–10 site summaries to develop with the template. A second team member then reviewed each summary to ensure consistent application of codes. The coding team held regular meetings to address questions on the application of codes.

3. Results

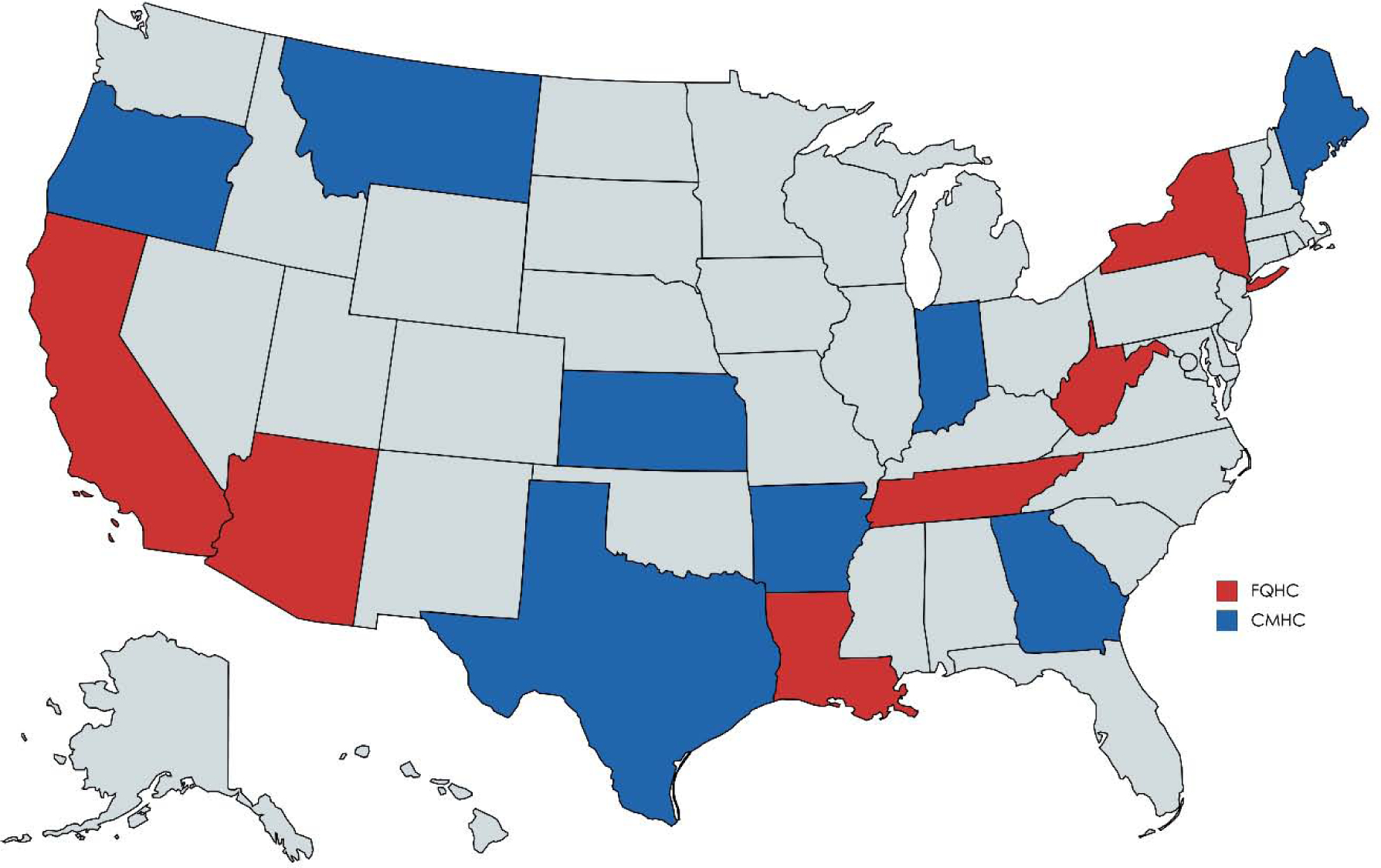

A total of 22 health centers with active telemedicine programs (11 FQHCs, 11 CMHCs) from 14 different states participated (Figure 1). Thirteen health centers were in rural areas only, eight had locations in both rural and urban areas, and one was only in urban areas (Table 1). Eight health centers had active tele-OUD programs, and 14 were nonadopters.

Figure 1: States represented among participating health centers.

Table 1:

Characteristics of participating health centers.

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Region | ||

| Northeast | 3 | 14 |

| West | 9 | 42 |

| South | 8 | 36 |

| Midwest | 2 | 10 |

| Number of Clinic Sites | ||

| 2–5 | 7 | 32 |

| 7–10 | 10 | 45 |

| 11+ | 5 | 23 |

| Location of Clinic Sites | ||

| Rural only | 13 | 59 |

| Urban only | 1 | 5 |

| Mix of rural and urban | 8 | 36 |

| % of patients with Medicaid | ||

| <50% | 8 | 36 |

| 51–69% | 10 | 45 |

| 70+% | 4 | 18 |

31. Services offered within tele-OUD programs

Among health centers with tele-OUD, the most common service provided via video was medication management for OUD (n=6) (Table 2). Centers prescribed OUD medications via telemedicine in isolation (n=3) or in combination with other tele-OUD services like counseling and psychotherapy (n=3). To comply with the Ryan Haight Act, several health centers required patients to meet with waivered (prescribing) providers in-person for the first visit. Subsequent visits could then occur via telemedicine. During these follow-up visits, patients often presented to medical assistants or nurses who staffed rural or smaller clinic locations. These in-person staff took vitals, coordinated lab testing, and sent results to the remotely located waivered prescribers. Patients were then seen via video by the waivered prescribers, often weekly.

Table 2:

Telemental health program services and staffing models.

| Org Type | State | Telemedicine Providers | Services Provided via Telemedicine | Tele-OUD Model Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMHC | Oregon | Psychiatrists and Nurse Practitioners |

|

Patients can present in clinic or receive telemedicine services at home through a mobile phone app. Group OUD services occur in-person at clinic only. |

| CMHC | Indiana | Psychiatrist and Nurse Practitioners |

|

Patients present in clinic and for urinalysis/drug screen and for tele- OUD visit. |

| FQHC | Arizona | Nurse Practitioner |

|

Patients present in clinic for tele-OUD visit. Counseling is generally provided in-person at a partner behavioral health organization. |

| FQHC | New York |

|

|

Patients presents in clinic for tele-OUD visit. First visit for prescribing done face-to-face with waivered provider but all follow-up visits are conducted with that provider via telemedicine. Local clinic staff manage urinalysis/drug screens. |

| FQHC | Tennessee | Licensed Clinical Social Worker |

|

Patients present in clinic for tele-OUD visits. Prescribing occurs in-person at the health center. |

| FQHC | West Virginia | Licensed Clinical Social Worker |

|

Patients present in clinic for tele-OUD visits. Prescribing occurs in-person with waivered family physicians at the health center. |

| FQHC | California |

|

|

Patients present in clinic for tele-OUD visits. First visit for prescribing done face-to-face with waivered provider but all follow-up visits are conducted with that provider via telemedicine. Local clinic staff manage urinalysis/drug screens. Psychotherapy can be delivered in-person or via telemedicine depending on patient preference |

| FQHC | California |

|

|

Patients present in clinic for tele-OUD visits. Local clinic staff manage urinalysis/drug screens. Psychoeducation and counseling done in-person at health center |

Two health centers offered only tele-counseling, with prescribing occurring in-person. For example, one health center contracted with a licensed clinical social worker for assessments and counseling via telemedicine for patients with OUD. At this health center, a subset of these patients were prescribed OUD medications in person. They had weekly, in-person visits with waivered family practice physicians, and met with a case manager multiple times per month.

Only one of the tele-OUD programs in the sample served patients in their homes via a mobile phone app. In all other cases, clinics delivered all services to patients presenting to a physical location. For example, a patient might be hosted at an understaffed rural location that is part of a large network of clinics.

3.2. Advantages and barriers to tele-OUD

Tele-OUD program representatives discussed a number of advantages as well as barriers to tele-OUD services. The most common advantage that representatives mentioned was the ability of tele-OUD to increase access and convenience, allowing patients to remain in their local community rather than travel long distances for treatment. One interviewee explained that the added convenience helped to secure patient buy in: “Clients have been pretty engaged about using tele-med. We ‘ve not had any significant amount of volume saying no I’m really not comfortable with that.”

A different interviewee, further, pointed out that tele-OUD services increased the capacity of the overall behavioral health system in her community. “They [a nearby substance abuse treatment center] will do some induction of MAT [medication assisted treatment] with some of their patients, and then they refer them to us for ongoing care, so they can now take on more new MAT patients.” Other interviewees pointed out that by allowing patients to access care in their primary clinic, telemedicine services reduced the stigma associated with seeking treatment. One health center representative mentioned that their providers found it beneficial to offer all OUD services within their own organization (through telemedicine) rather than referring out, which can result in fragmented medical data on patients. Barriers that tele-OUD program representatives mentioned included the Ryan Haight Act, which generally requires an in-person visit prior to the prescribing of controlled substances, and difficulties in getting lab results (e.g., urine toxicology screenings) to distant (prescribing) providers.

The one health center that offered tele-OUD to patients in their homes via a mobile app pointed out some unique issues with this delivery model. First, treatment still required patients to travel some (e.g., urinalysis must be completed in a medical setting). Second, visits from home would not work for all patient populations. The representative from this health center explained, “We’ve had some limitations with some of our alcohol and drug mandated population, where probation officers want the person to be on-site [rather than at home] for accountability.”

3.3. Reasons for nonadoption

Nonadopters cited several reasons for not offering tele-OUD services. The leading reason was regulatory barriers such as the Ryan Haight Act. One interviewee explained that his health center “felt hindered by the face-to-face requirement.” A different interviewee reported, “[Ryan Haight] pretty much shuts down being able to do buprenorphine treatment in rural locations.” Several interviewees commented that they were likely to pursue tele-OUD in the future given recent policy changes that are likely to relax this requirement. A handful of health center representatives mentioned that they chose not to implement tele-OUD services because group visits (common in OUD treatment) were either challenging to deliver via telemedicine or were not reimbursable (e.g., due to state Medicaid policies.) An interviewee explained, “In drug treatment, you do a ton of group work. I don’t know if we will ever figure out a way to have tele-video in group services.” Several other nonadopters explained that they did not offer telemedicine for patients with OUD because they were only prescribing OUD medications in one or two locations and had adequate in-person staff at those sites. One nonadopter explained that her health center had only just begun offering OUD medications and staff wanted to gain experience prior to expanding into telemedicine.

4. Discussion

In interviews with tele-OUD adopters and nonadopters, we explored delivery models as well as benefits and barriers to tele-OUD. We found that although there are examples of health centers offering tele-OUD, many telemental health providers with the necessary infrastructure have yet to expand into tele-OUD.

Furthermore, there is no single way that tele-OUD is being deployed; rather, health centers are using telemedicine for a variety of services and may offer a single service (e.g., medication management only) or multiple services (e.g., assessment, medication management, individual therapy, group therapy) via telemedicine. Both adopters and nonadopters identified issues with the Ryan Haight Act, suggesting that the 2018 SUPPORT Act appropriately targeted a major barrier to the growth of tele-OUD. While many stakeholders are hopeful that allowing organizations to register with the Drug Enforcement Administration to bypass the in-person visit requirement will open up opportunities in tele-OUD, the legislation itself is ambiguous and to date, no final regulations detailing the procedure for obtaining a special registration have been issued (Acosta & Lacktman, 2018; National Law Review, 2018). To effectively address the barrier that the Ryan Haight Act erected, the process to obtain a special registration will likely have to be straightforward and low cost. Furthermore, Ryan Haight was not the only barrier to the delivery of tele-OUD that we identified. To encourage health centers to utilization tele-OUD, centers will need to improve workflow as well as develop logistical and regulatory solutions for the provision of group visits.

A key limitation of this research is that we sampled only CMHCs and FQHCs. As such, the implementation models and themes that we identified may not apply or may be experienced differently in other behavioral health organizations (e.g., psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment facilities). Although describing delivery models currently in use can inform practical strategies as well as new policies to promote the growth of tele-OUD, future work should evaluate the long-term impact of the SUPPORT Act as it is actually implemented and should explore how other behavioral health organizations in the U.S. use tele-OUD.

Highlights.

Among health centers with tele-OUD, the most common service provided was medication management.

Leading barriers for adopters included regulations on the prescribing of controlled substances including buprenorphine and difficulties in sending lab results to distant providers.

Non-adopters reported not offering tele-OUD due to regulations in controlled substance prescribing, complexities and regulatory barriers to offering group visits, and the belief that in-person OUD services were meeting patient need.

Describing current tele-OUD delivery models can inform strategies to promote and implement tele-OUD to combat the opioid epidemic.

Funding Statement:

This project was supported by NIDA (R01 DA048533) Word Count: 1500

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Acosta J, & Lacktman N. (2018). President Signs New Law Allowing Telemedicine Prescribing of Controlled Substances: DEA Special Registration to Go Live. https://www.foley.com/en/insights/publications/2018/10/president-signs-new-law-allowing-telemedicine-pres. Accessed September 15, 2019.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. (2015). The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Association for Behavioral Health and Wellness. (2016). Advocacy: Telehealth. http://www.abhw.org/issues/. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Center for Connected Health Policy. (2018). Opportunities and Challenges to Utilizing Telehealth Technologies in the Provision of Medication Assisted Therapies in the Medi-Cal Program.

- Huskamp HA, Busch A, Substance Use Disorder Treatment? Souza J, et al. (2018). How Is Telemedicine Being Used In Opioid And Other Health Aff (Millwood), 37(12), 1940–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauckner C, & Whitten P. (2016). The State and Sustainability of Telepsychiatry Programs. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 43(2), 305–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebelt ERS, Nathan I, & Bruland P (2017). Telehealth as Means to Diagnose and Treat Opioid Abuse. HIMSS. https://www.himss.org/news/telehealth-means-diagnose-and-treat-opioid-abuse. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Lin LA, Casteel D, Shigekawa E, Weyrich MS, Roby DH, & McMenamin SB. (2019). Telemedicine-delivered treatment interventions for substance use disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 101, 38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter T, Boyle M, Holloway D, & Zwick J (2015). Trends in telemedicine use in addiction treatment. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 10, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2018). NAMI Policy Brief: Mental Illness and the Opioid Crisis. https://www.sheriffs.org/sites/default/files/NAMI%20Mental%20Illness%20and%20the%20Opioid%20Crisis.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- National Law Review. (2018). SUPPORT Act Expands Telehealth Treatment for Substance Use Disorders. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/support-act-expands-telehealth-treatment-substance-use-disorders.

- The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. (2017). https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Final_Report_Draft_11-1-2017.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rapp RC, Xu J, Carr CA, Lane DT, Wang J, & Carlson R (2006). Treatment barriers identified by substance abusers assessed at a centralized intake unit. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(3), 227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, & Karthikeyan S (2015). Changes in Substance Abuse Treatment Use Among Individuals With Opioid Use Disorders in the United States, 2004–2013. JAMA, 314(14), 1515–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). CCBHCs Using Telehealth or Telemedicine. https://www.samhsa.gov/section-223/care-coordination/telehealthtelemedicine. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2018. [PubMed]