Abstract

Approximately 370–500 million Indigenous people live worldwide. While Indigenous peoples make up only 5% of the world’s population, they account for 15% of the extreme poor and have life expectancy that is 20 years shorter than that of non-Indigenous people. Access to healthcare has been identified as an important social determinant of health and key driver of health outcomes. Indigenous populations often face barriers to accessing healthcare including living in remote areas, lacking financial resources, and having cultural differences. Telehealth, the utililzation of any synchronous modality, including phone, video, or teleconferencing technology used to support the provision of long-distance health care and health education, is a feasible and cost-effective treatment delivery mechanism that has successfully addressed access barriers faced by vulnerable populations globally, however, few studies have included indigenous populations and the application of this technology to improve physical and mental health outcomes. This systematic review aims to identify trials that were conducted among Indigenous adults, and to summarize the components of interventions that have been found to effectively improve the health of Indigenous peoples. The PRISMA guidelines for reporting of systematic reviews were followed in preparing this manuscript. Studies were identified by searching PubMed, Scopus, and PsychInfo databases for clinical trial articles on Indigenous peoples and mental and physical health, published between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2018. Eligibility criteria for determining studies to include in the analysis were as follows: (I) ≥18 years of age; (II) indigenous peoples; (III) any technology-based intervention; (IV) studies included at least one of the following mental health (depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide) and physical health (mortality, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C, cholesterol, quality of life) outcomes; (V) clinical trials. A total of 2,662 articles were identified and six were included in the final review based on pre-specified eligibility criteria. Three were conducted in the United States, one study was conducted in Canada, and two were conducted in New Zealand. Study sample sizes ranged from 20 to 762, intervention delivery times ranged from three to 20 months and utilized telephone, internet and SMS messaging as the type of technology. There is a paucity of evidence on the use of telehealth programs to increase access to chronic disease programs in Indigenous populations. This review highlights the importance of culturally tailoring programs despite the modality in which they are delivered, and recommends telephone-based delivery facilitated by a trained health professional. Telehealth has great promise for meeting the health needs of highly marginalized Indigenous populations around the world, however, at this point more research is needed to understand how best to structure and deliver these programs for maximum effect.

Keywords: Telehealth, telemedicine, indigenous, mental health, physical health

Introduction

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct societies and communities that practice unique traditions, and retain social, cultural, economic, and political characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live (1-4). Due to the diversity of Indigenous peoples, the United Nations has not adopted an official definition of the term Indigenous, but has developed a set of descriptive characteristics of this group: (I) Indigenous peoples should self-identify as Indigenous and be accepted as a member of the community, (II) have historical continuity with pre-colonial societies, (III) have a strong link to territories and surrounding natural resources, (IV) have distinct social, economic or political systems, (V) have distinct languages and culture that differ from the dominant society, and (VI) be a non-dominant group of society (1-4). Approximately 370–500 million Indigenous people live worldwide, across more than 90 countries (3), and representing more than 5,000 cultures (4). While Indigenous peoples make up only 5% of the world’s population, they account for 15% of the extreme poor (3) and are more likely to suffer from malnutrition and have inadequate economic resources (4). The life expectancy of Indigenous peoples is 20 years shorter than that of non-Indigenous people worldwide (3-5). The high burden of mortality has been associated with Indigenous populations lacking adequate healthcare, health information, and being more susceptible to communicable diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) (4).

Across the world, lower income communities have needed to shift from a focus on primarily communicable to a combination of communicable and noncommunicable diseases (6). While much of reported data indicate lower prevalence of chronic disease among Indigenous peoples compared to non-Indigenous communities, more recent studies have found Indigenous groups to be at higher risks of chronic diseases such as diabetes and prediabetes (7). For example, fifty percent of Indigenous adults over the age of 35 have type 2 diabetes around the world (5) and more than half of Indigenous Australians over the age of 55 report suffering from heart or circulatory diseases (8). Indigenous peoples are not only plagued by physical health ailments such as malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS, but are also severely impacted by mental health conditions (9). Indigenous groups have been found to be at high risk of and have increased mortality due to mental illnesses such as depression and serious psychological distress (SPD) (10) because of unemployment, social marginalization (11,12), and loss of cultural lands and identity compared to non-Indigenous peoples (9,13).

Access to healthcare has previously been identified as an important social determinant of health and a key driver of health outcomes (14). Five widely recognized dimensions of access to healthcare include (I) approachability, (II) acceptability, (III) availability and accommodation, (IV) affordability, and (V) appropriateness (15-17). Approachability is the concept of individuals with health needs are able to identify that services exist, can be reached, and will have an impact on their health (15,16). Acceptability refers to the cultural and social factors that determine the likelihood of individuals accepting the service (15-17). Availability and accommodation refer to the idea of health services being accessible physically, and in a timely manner (15,16). Affordability is one’s economic and ability to spend resources and time utilizing services (15-17). Lastly, appropriateness refers to the needed services, clients’ needs, timeliness, and the amount of time and care addressing the individual’s problem (15,16). Indigenous populations are often faced with multiple barriers impacting dimensions of the access continuum. Barriers including living in remote areas, poverty and lack of financial resources, cultural differences from majority populations, and lack of trust in the healthcare system all contribute to the inadequate access and utilization of health care services.

Telehealth is a feasible and cost-effective treatment delivery mechanism that has successfully addressed access barriers to healthcare services faced by diverse underserved and vulnerable populations around the world (18-20). The domain most often focused on is telehealth’s ability to increase access through reduction of the need to travel, and increasing availability of specialists in areas with limited services (21-24). Additionally, research has shown that health promoting interventions delivered via telehealth modalities can be culturally tailored to fit the needs of diverse communities and ethnic/racial minorities (25).

Although the telehealth literature is robust, few studies have included or focused on Indigenous populations specifically and the application of this technology to improve physical and mental health outcomes (26). Given the cultural considerations of Indigenous communities, increasing access to care via telehealth simply through increased availability, without consideration of other domains such as acceptability and appropriateness, highlight a need to investigate the evidence base for telehealth in Indigenous populations. To our knowledge, no review exists summarizing telehealth interventions conducted among Indigenous people to improve mental health (mortality, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide) and physical health outcomes (hypertension, hemoglobin A1C, high cholesterol, quality of life). This systematic review aims to identify trials that were conducted among Indigenous adults, and to summarize the components of interventions that have been found to effectively improve the health of Indigenous peoples around the world. This summary and new knowledge will be used to develop and tailor more robust programs to improve the health of this vulnerable population.

Methods

Search term selection, eligibility criteria, search strategy

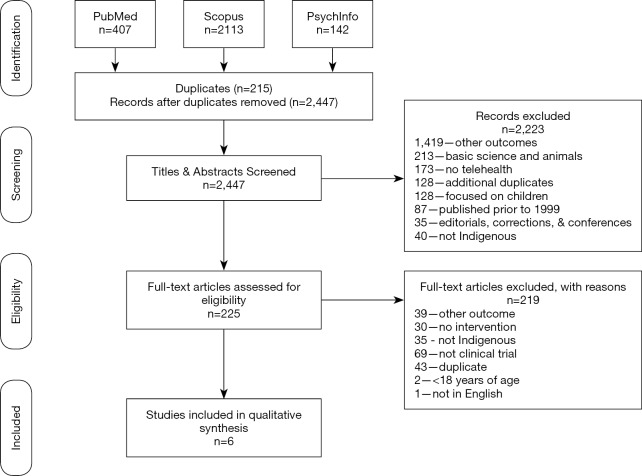

The PRISMA guidelines for reporting of systematic reviews were followed in preparing this manuscript (27). The PRISMA guidelines include a checklist of items that should be included when reporting findings from a systematic review. We have included the recommended diagram in Figure 1 that shows the number of articles identified, excluded, and included in the review (27). The PICOS (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design) approach was used to define study eligibility criteria (27). A reproducible method was used to identify previously published manuscripts on interventions using telehealth to address chronic disease and improve health outcomes among Indigenous peoples around the world. We defined telehealth as any synchronous modality, including phone, video, or teleconferencing technology, but did not include store-and-forward (S&F). We defined chronic disease as both physical and mental chronic and noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and depression. Indigenous people were defined as any self-identified Indigenous group, as specified by the author of the reviewed paper.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for eligible article selection.

Studies were identified by searching PubMed, Scopus, and PsychInfo databases for clinical trial articles on Indigenous peoples and mental and physical health, published between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2018. The search terms were based on search strategies identified in Cochrane reviews and other systematic reviews for Indigenous peoples (28-30), telehealth (31,32), mortality (33), depression (34-36), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (37,38), suicide (35,39,40), blood pressure (41-43), hemoglobin A1C (44,45), cholesterol (46-48), and quality of life (49-51). Some identified search terms were not used given the study goal, for example we did not include acute mental conditions such as psychosis or schizophrenia and instead selected terms for chronic mental and physical health conditions, such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide, mortality, hemoglobin A1C, cholesterol, and hypertension. Search terms can be found in the appendix.

The eligibility criteria for determining studies to include in the analysis were as follows: participants: (I) at least 18 years of age or older, (II) indigenous peoples; interventions: (III) any technology-based intervention (telephone, cell phone, video, mobile application, computer-based); comparisons: (IV) control, (V) usual care, (VI) other interventions; outcomes—the study included at least one of the following outcomes: (VII) mental health (depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide), (VIII) physical health (mortality, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C, cholesterol, quality of life); study design: (IX) clinical trials (randomized control trials, quasi-experimental, cohort (prospective or retrospective). Cross-sectional studies were excluded. Both physical and mental health outcomes were included due to the paucity of literature and clinical trials where Indigenous peoples are included in the study or identified in the sample demographics and results. The search strategy has been outlined in Tables 1-4 of the supplementary materials.

Table 1. Structure of search and search terms for PubMed.

| Search # | Search terms | Number of articles found |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aborig* OR Indig* OR Indigenous OR Inuit OR Maori OR Native American OR American Indian OR Tribe OR Tribal OR [Aotearoa[tw] AND Oceanic ancestry group[mh]] OR American Native continental ancestry group[mh] OR [Torres Strait[tw] AND islander*[tw]] OR Inuit*[tw] OR Eskimo*[tw] OR Native[tw] OR First Nation*[tw] | 270,930 |

| 2 | Telemedicine OR Telemetry OR Telehealth OR Computer Communication Networks OR Online Systems OR Computer-Assisted Diagnosis OR Handheld Computers OR Internet OR Microcomputers OR Telecommunications OR Remote Consultation OR Telenursing OR Videoconferencing OR Teleconferencing OR Teleconsultation OR Telediagnosis OR Telemonitoring OR Teletherapy OR Teleconference OR Online Therapy OR Tele-health OR Telemedicine OR tele-medicine OR telerehab* OR tele-rehab* OR telediagnos* OR tele-diagnos* OR teletreat* OR tele-treat OR teletherap* OR tele-therap* OR telemonitoring OR tele-monitoring OR teleintervention OR - tele-intervention OR teletreatment OR tele-treatment OR telepractice OR tele-practice OR videoconference* OR video-conferenc* OR teleconference* OR tele-conference* OR webbased OR web-based OR internet-based OR [technology AND mediated] OR technology-mediated | 348,898 |

| 3 | Mortality OR Survival OR Mortality | 1,900,059 |

| 4 | Depress* OR dysthymi* OR mood disorder* OR affective disorder* OR affective symptom* OR depressed OR depression OR depression OR depressive disorder OR major depressive disorder OR major depression OR major depressive disorder OR MDD OR Sadness OR Depressive symptoms OR Depressive OR major depression disorder OR emotion* OR mental disorders OR psychiatric disorders | 1,633,020 |

| 5 | PTSD OR posttrauma* OR post-trauma* OR post trauma* OR combat disorder OR stress disorder OR trauma* | 397,482 |

| 6 | Ideation OR suicid* OR suicide OR Suicide OR Suicidality OR suicidal ideation OR Self-harm OR attempted suicide OR parasuicide OR self-injur* OR self-poison* OR suicide* OR posttraumatic stress symptom* OR post-traumatic stress symptom* | 98,767 |

| 7 | Hypertension OR arterial hypertension OR high blood pressure OR elevated blood pressure OR hypertensive patients OR target level OR target blood pressure OR target systolic blood pressure OR target diastolic blood pressure OR Hypertens* OR blood-pressure* OR bp OR sbp OR dbp OR hypertensive* OR hypertension* OR hypertension* OR blood pressure measurement | 878,406 |

| 8 | Glycosylated haemoglobin OR HbA1c OR hemoglobin levels OR glycated haemoglobin OR hemoglobin A1c OR Glycosylated hemoglobin A OR Hemoglobins OR hemoglobin A OR glycat* OR glycosylat* OR hemoglobin* OR haemoglobin* OR hemo-globin* OR haemoglobin* OR hba1c OR hb a1c OR hbaic OR hb aic OR ic OR 1c OR Aic OR a1c OR hemoglobin* OR haemoglobin* OR hemo-globin* OR haemoglobin* OR hb OR hba OR glycohemoglobin OR glycol-hemoglobin OR glycol-haemoglobin OR glycohaemoglobin |

372,097 |

| 9 | Cholesterol* OR epicholesterol* OR azacosterol* OR diazacholesterol* OR hydroxycholesterol* OR 19-iodocholesterol* OR iodocholesterol* OR ketocholesterol* OR oxocholesterol* OR lipid* OR glyceride* OR triglyceride* OR glycolipid* OR ipoprotein* OR ldl OR hdl OR Cholesterol OR Hypercholesterolemia OR Dyslipidemia OR Cholesterol OR Lipids OR Dyslipidemia OR Hypercholesterolemia OR total cholesterol | 838,686 |

| 10 | Quality of life OR QoL OR mental health OR emotional wellbeing OR psychological wellbeing OR emotional well-being OR psychological well-being OR quality of life OR Short-Form Health Survey OR SF-12 OR SF-36 OR SF12 OR SF 12 OR SF36 OR SF 36 OR life quality | 465,490 |

| 11 | #1 AND #2 | 2,011 |

| 12 | #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 | 5,750,607 |

| 13 | #11 AND #12 | 405 |

Regular text—text word used; Italic text—MeSH Terms used.

Table 2. Structure of search and search terms for Scopus.

| Search # | Search terms | Number of articles found |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aborig* OR Indig* OR Indigenous OR Inuit OR Maori OR Native American OR American Indian OR Tribe OR Tribal OR [Aotearoa AND Oceanic ancestry group] OR American Native continental ancestry group OR Torres Strait AND islander* OR Inuit* OR Eskimo* OR Native OR First Nation* | 812,809 |

| 2 | Telemedicine OR Telemetry OR Telehealth OR Computer Communication Networks OR Online Systems OR Computer-Assisted Diagnosis OR Handheld Computers OR Internet OR Microcomputers OR Telecommunications OR Remote Consultation OR Telenursing OR Videoconferencing OR Teleconferencing OR Teleconsultation OR Telediagnosis OR Telemonitoring OR Teletherapy OR Teleconference OR Online Therapy OR Tele-health OR Telemedicine OR tele-medicine OR telerehab* OR tele-rehab* OR telediagnos* OR tele-diagnos* OR teletreat* OR tele-treat* OR teletherap* OR tele-therap* OR telemonitoring OR tele-monitoring OR teleintervention OR tele-intervention OR teletreatment OR tele-treatment OR telepractice OR tele-practice OR videoconference* OR video-conferenc* OR teleconference* OR tele-conference* OR webbased OR web-based OR internet-based OR [technology AND mediated] OR technology-mediated | 1,349,190 |

| 3 | Mortality OR Survival | 2,516,278 |

| 4 | Depress* OR dysthymi* OR mood disorder* OR affective disorder* OR affective symptom* OR depressed OR depression OR depressive disorder OR major depression OR major depressive disorder OR MDD OR Sadness OR Depressive symptoms OR Depressive OR major depression disorder OR emotion* OR mental disorders OR psychiatric disorders | 1,555,425 |

| 5 | PTSD OR posttrauma* OR post-trauma* OR post trauma* OR combat disorder OR stress disorder OR trauma* posttraumatic stress symptom* OR post-traumatic stress symptom* | 684,105 |

| 6 | Ideation OR suicid* OR Suicide OR Suicidality OR suicidal ideation OR Self-harm OR attempted suicide OR parasuicide OR self-injur* OR self-poison* OR suicide* OR | 148,132 |

| 7 | Hypertension OR arterial hypertension OR high blood pressure OR elevated blood pressure OR hypertensive patients OR target level OR target blood pressure OR target systolic blood pressure OR target diastolic blood pressure OR Hypertens* OR blood-pressure* OR bp OR sbp OR dbp OR hypertensive* OR hypertension* OR blood pressure measurement | 1,765,236 |

| 8 | Glycosylated haemoglobin OR HbA1c OR hemoglobin levels OR glycated haemoglobin OR hemoglobin A1c OR Glycosylated hemoglobin A OR Hemoglobins OR hemoglobin A OR glycat* OR glycosylat* OR hemoglobin* OR haemoglobin* OR hemo-globin* OR haemoglobin* OR hba1c OR hb a1c OR hbaic OR hb aic OR ic OR 1c OR Aic OR a1c OR hemoglobin* OR haemoglobin* OR hemo-globin* OR hb OR hba OR glycohemoglobin OR glycol-hemoglobin OR glycol-haemoglobin OR glycohaemoglobin | 603,605 |

| 9 | Cholesterol* OR epicholesterol* OR azacosterol* OR diazacholesterol* OR hydroxycholesterol* OR 19-iodocholesterol* OR iodocholesterol* OR ketocholesterol* OR oxocholesterol* OR lipid* OR glyceride* OR triglyceride* OR glycolipid* OR lipoprotein* OR ldl OR hdl OR Cholesterol OR Lipids OR Dyslipidemia OR Hypercholesterolemia OR total cholesterol | 1,210,679 |

| 10 | Quality of life OR QoL OR mental health OR emotional wellbeing OR psychological wellbeing OR emotional well-being OR psychological well-being OR Short-Form Health Survey OR SF-12 OR SF-36 OR SF12 OR SF 12 OR SF36 OR SF 36 OR life quality | 1,015,821 |

| 11 | #1 AND #2 | 13,746 |

| 12 | #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 | 7,991,586 |

| 13 | #11 AND #12 | 2,113 |

All words were searched as: article title, abstract, keywords.

Table 3. Structure of search and search terms for PsychInfo.

| Search # | Search terms | Number of articles found |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aborig* OR Indig* OR Indigenous OR Inuit OR Maori OR Native American OR American Indian OR Tribe OR Tribal OR [Aotearoa AND Oceanic ancestry group] OR American Native continental ancestry group OR Torres Strait AND islander* OR Inuit* OR Eskimo* OR Native OR First Nation* | 47,630 |

| 2 | Telemedicine OR Telemetry OR Telehealth OR Computer Communication Networks OR Online Systems OR Computer-Assisted Diagnosis OR Handheld Computers OR Internet OR Microcomputers OR Telecommunications OR Remote Consultation OR Telenursing OR Videoconferencing OR Teleconferencing OR Teleconsultation OR Telediagnosis OR Telemonitoring OR Teletherapy OR Teleconference OR Online Therapy OR Tele-health OR Telemedicine OR – 4,997 tele-medicine OR telerehab* OR tele-rehab* OR telediagnos* OR tele-diagnos* OR teletreat* OR tele-treat OR teletherap* OR tele-therap* OR telemonitoring OR tele-monitoring OR teleintervention OR tele-intervention OR teletreatment OR tele-treatment OR telepractice OR tele-practice OR videoconference* OR video-conferenc* OR teleconference* OR tele-conference* OR webbased OR web-based OR internet-based OR technology AND mediated OR technology-mediated | 72,862 |

| 3 | Mortality OR Survival OR | 73,338 |

| 4 | Depress* OR dysthymi* OR mood disorder* OR affective disorder* OR affective symptom* OR depressed OR depression OR depressive disorder OR major depressive disorder OR major depression OR MDD OR Sadness OR Depressive symptoms OR Depressive OR major depression disorder OR emotion* OR mental disorders OR psychiatric disorders | 756,589 |

| 5 | PTSD OR posttrauma* OR post-trauma* OR post trauma* OR combat disorder OR stress disorder OR trauma* OR posttraumatic stress symptom* OR post-traumatic stress symptom* | 126,773 |

| 6 | Ideation OR suicid* OR Suicide OR Suicidality OR suicidal ideation OR Self-harm OR attempted suicide OR parasuicide OR self-injur* OR self-poison* OR suicide* OR | 72,245 |

| 7 | Hypertension OR arterial hypertension OR high blood pressure OR elevated blood pressure OR hypertensive patients OR target level OR target blood pressure OR target systolic blood pressure OR target diastolic blood pressure OR Hypertens* OR blood-pressure* OR bp OR sbp OR dbp OR hypertensive* OR hypertension* OR blood pressure measurement | 36,392 |

| 8 | Glycosylated haemoglobin OR HbA1c OR hemoglobin levels OR glycated haemoglobin OR hemoglobin A1c OR Glycosylated hemoglobin A OR Hemoglobins OR hemoglobin A OR glycat* OR glycosylat* OR hemoglobin* OR haemoglobin* OR hemo-globin* OR haemoglobin* OR hba1c OR hb a1c OR hbaic OR hb aic OR ic OR 1c OR Aic OR a1c OR hemoglobin* OR haemoglobin* OR hemo-globin* OR hb OR hba OR glycohemoglobin OR glycol-hemoglobin OR glycol-haemoglobin OR glycohaemoglobin | 10,482 |

| 9 | Cholesterol* OR epicholesterol* OR azacosterol* OR diazacholesterol* OR hydroxycholesterol* OR 19-iodocholesterol* OR iodocholesterol* OR ketocholesterol* OR oxocholesterol* OR lipid* OR glyceride* OR triglyceride* OR glycolipid* OR lipoprotein* OR ldl OR hdl OR Cholesterol OR Lipids OR Dyslipidemia OR Hypercholesterolemia OR total cholesterol | 18,769 |

| 10 | Quality of life OR QoL OR mental health OR emotional wellbeing OR psychological wellbeing OR emotional well-being OR psychological well-being OR Short-Form Health Survey OR SF-12 OR SF-36 OR SF12 OR SF 12 OR SF36 OR SF 36 OR life quality | 280,208 |

| 11 | #1 AND #2 | 716 |

| 12 | #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 | 1,111,396 |

| 13 | #11 AND #12 | 142 |

Black text—keyword (with box for map term to subject heading unchecked).

Table 4. Search results uploaded to EndNote.

| Database | Number returned | Number uploaded | Number of duplicates discarded | Number uploaded to EndNote |

Final number in EndNote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | 408 | 407 | 0 | 407 | 407 |

| Scopus | 2,113 | – | 215 | 1,898 | 2,305 |

| PsychInfo | 142 | 142 | 0 | 142 | 2,447 |

Study selection and data collection

Figure 1 outlines the process used to identify eligible articles. Titles and abstracts were reviewed to ensure the study (I) targeted Indigenous peoples, (II) used telehealth as the intervention, and (III) assessed at least one outcome of interest. Articles were eliminated if they did not meet the pre-specified eligibility criteria. Full articles were then read and reviewed by four independent reviewers (AZ Dawson, RJ Walker, JA Campbell, TM Davidson). Each reviewer used the participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) approach to further assess article eligibility. As articles were reviewed, data was collected by each reviewer using a standardized data collection form that included the following headings: author, year, country, Indigenous group, study type, number of participants, age, other inclusion criteria, incentives, intervention description, cultural tailoring, technology used, mode of delivery, length of intervention, follow-up, outcomes, and results. Data collected from each eligible article is shown in Tables 5-8. Quality of the included manuscripts was not assessed due to the limited number of papers meeting eligibility criteria.

Table 5. Descriptive characteristics of studies meeting eligibility criteria.

| Author | Year | Country | Indigenous group | Study type | Number of participants | Age | Other inclusion criteria | Incentives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer et al. | 2012 | USA | American Indian | RCT | 762 | >17 years | N/A | N/A |

| Lorig et al. | 2010 | USA | American Indian/Alaska Native | RCT (the AI/AN were enrolled in the study as a subgroup using waitlist control) | 761 were randomized, 732 continued in the study for 6 months, 645 completed the 6-month questionnaire. 528 non-AI/AN completed the 18-month questionnaire. AI/AN recruitment included 110 participants | ≥18 years | Physician verified T2DM and access to the internet | $10 Amazon.com certificate |

| Tobe et al. | 2018 | Canada | First Nations | RCT of two types of messaging | 243 adults living on reservation with uncontrolled hypertension (122 included in the analysis) | ≥18 years | Uncontrolled hypertension and stable on antihypertensives for at least 8 weeks if taking medication, have a cell-phone capable of receiving SMS messages or be willing to learn how to use a basic flip phone for use during the study. Have a current primary care provider | N/A |

| Venter et al. | 2012 | New Zealand | Maori | RCT | 20 | No mention | Patients discharged from the hospital in the previous 12–24 months with a diagnosis of CHF or COPD | N/A |

| Whealin | 2017 | USA | Pacific Island Veterans | Pilot pre-post intervention | 28 Veterans and 28 family members |

no mention | Veterans with PTSD and report of relationship problems | N/A |

| Williams | 2017 | New Zealand | Maori | RCT of two delivery modalities | 68 Maori and 70 New Zealand Europeans with T2DM | No mention | N/A | N/A |

Table 6. Intervention description of studies meeting eligibility criteria.

| Author | Year | Intervention description | Cultural tailoring | Technology used | Mode of delivery | Length of intervention | Follow-up | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer et al. (Fischer et al. 2008 describes intervention) | 2012 | Telephone outreach program delivered by research nurses. Nurses followed lipid management algorithms, checked labs and titrated lipid lowering medications. Nurses were trained to address other aspects of diabetes care: blood pressure control, blood sugar control, nephropathy, eye screening, vaccines, obesity, and cigarette smoking. Nurses were also trained in motivational interviewing | N/A | Telephone | Telephone | 20 months | N/A | LDL <100 mg/dL. Number of hospital admissions. Total hospital charges per patient. Proportion of patients meeting other lipid, glycemic, and blood pressure guidelines | Percent of patients with LDL <100 increased for those in intervention (from 52–58.5%), where the percent decreased for those in usual care (from 55.6% to 46.7%) P<0.01. A higher percent of intervention participants achieved the LDL goal of <100 (69.1% vs. 46.7%, P<0.01) |

| Lorig et al. | 2010 | 6 weekly sessions where participants logged on individually. Program materials were offered in 20–30 new web pages weekly. Each week participants responded to questions such as “what problems do you have because of your diabetes?” and developed an action plan. Questions and action plans were posted to the online Discussion platform where other participants could see the information. Two peer facilitators assisted participants by reminding them to log on, modeling action planning, problem solving, and encouraging the participants. Programs were facilitated by 16 individuals, ½ with diabetes | N/A | Internet | Internet | 6 months | 18 months | HbA1C. Health distress. Activity limitation | At 6 months, the AI/AN subgroup was underpowered (n=73). There was a significant decrease in health distress and activity limitation. Treatment group had a significant increase in physician visits |

| Tobe et al. | 2018 | Changes, management of hypertension; blood pressure measurements taken by CHW and transmitted to provider | Messages tested for cultural safety and understanding | Phones—text messaging | Active or passive messaging | 12 months | Blood pressure | Overall reduction in blood pressure over the study, but no difference in blood pressure change between groups from baseline to 12-months for systolic or diastolic. No difference in proportion that achieved blood pressure control between the two groups | |

| Venter et al. | 2012 | A telehealth terminal was installed in each of the intervention participants’ home, with an online link to a portal that was checked regularly by nurses. The telehealth terminal was composed of a touch-screen computer that allowed to check their body weight, oxygen levels, lung function, blood pressure. Results were transmitted over telephone lines to a central computer and included a web-based patient record. Nurses used the patient record to monitor patients and to decide if patients needed clinical intervention. Both usual care and intervention patients received a nurse-led disease management program that involved regular home visits and care planning | N/A | Touch screen computer that measured body weight, oxygen levels, lung function, and blood pressure | Web-based and face-to-face | 12 months | 12 months | Mortality, quality of life, blood pressure | The telehealth group showed improved quality of life (P<0.02), and a non-statistically significant trend towards decreased mortality |

| Whealin | 2017 | Psychoeducational program integrating Pacific Islander values, beliefs, and healing traditions with empirically based cognitive behavioral intervention | Incorporated values, beliefs, and healing traditions of Pacific Islanders; and incorporated family into intervention delivery | Teleconference | Teleconference | 3 months | N/A | Relationship quality scores, family caregiving burden | Relationship quality scores substantially improved post-intervention as measured by the Dyadic Relationship Scale (95% CI: −10.97, −1.84) |

| Williams et al. | 2017 | Lifestyle intervention. Participants received monthly on-on-one support for 6-months either by face-to-face or telephone. A Maori Green Prescription facilitator trained in nutrition, physical activity and motivational interviewing delivered the program. Physical exercise (walking, swimming, washing clothes, gardening, etc.) and a healthy eating plan was decided on and support materials were provided | Integrated a Maori culturally sensitive approach | Telephone vs. face-to-face | Telephone vs.

face-to-face |

Monthly support for 6 months | 6 months | Anthropometry. Blood lipids. HbA1C | Overall reduction in weight [1.8; (95% CI: 0.6, 2.9 kg)]. Waist circumference [3.7 (2.6, 4.8 cm)]. Total cholesterol [0.6 (0.3, 0.9 mmol/L)]. HBa1C [3.1 (−0.2, 6.7 mmol/mol)]. There were no significant differences by mode of delivery, ethnicity or gender |

Table 7. Study characteristics summary.

| Study author, year | Statistically significant outcome | Cultural tailoring | Incentive | Peer-led | Health professional (nurse, doctor, etc.)—led | Group-based | Web-based | Telephone- based |

SMS | Video | Technology + human delivery | Veteran population | Knowledge building | Skills training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer et al., 2012 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Lorig et al., 2010 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Tobe et al., 2018 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Venter et al., 2012 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Whealin et al., 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Williams et al., 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Table 8. Study duration summary.

| Study author, year | Statistically significant outcome | Length of intervention (months) | Length of follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3 | 3–9 | 9–12 | >12 | <3 | 3–9 | 9–12 | >12 | |||

| Fischer et al., 2012 | x | x | ||||||||

| Lorig et al., 2010 | x | x | ||||||||

| Tobe et al., 2018 | x | |||||||||

| Venter et al., 2012 | x | x | ||||||||

| Whealin et al., 2017 | x | |||||||||

| Williams et al., 2017 | x | x | ||||||||

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 shows the results of the search. Articles were reviewed for eligibility in a systematic fashion. A total of 2,662 articles were identified after searching PubMed, Scopus, and PsychInfo databases. Two hundred fifteen duplicates were identified and removed after uploading search results to EndNote, leaving 2,447 eligible for initial reviews. Two hundred twenty-five [225] remained for full-text review after excluding 2,223 during the title and abstract review. An additional 219 were deemed ineligible for inclusion in the analysis with reasons outlined in Figure 1. Six articles were included in the final review based on pre-specified eligibility criteria.

Study characteristics

Tables 5-8 provide a summary of the characteristics of the six studies that met eligibility criteria. Three studies were conducted in the United States (52-54), one study was conducted in Canada (55), and two studies were conducted in New Zealand (56,57). Included Indigenous groups were: American Indian/Alaska Native (52,53), Maori (56,57), and First Nation (55). Many of the papers on United States Veterans were excluded due to the sole reporting of lessons learned during program development, productivity measures or intervention acceptability; and a lack of reporting on physical or mental health outcomes. Future research should closely examine Indigenous Veteran and non-Veteran populations to understand whether telehealth interventions are equally efficacious or require different tailoring. Most of the studies were randomized control trials (52,53,55-57), and one used a pre-post study design (54). Only one out of the six studies reported providing incentives for the study participants (53). Study sample sizes ranged from 20 to 762. The intervention delivery times ranged from three to 20 months and utilized telephone, internet and SMS messaging as the type of technology. Three studies reported culturally tailoring the intervention (54,55,57). Outcomes of interest included low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (52,54), hemoglobin A1C (53,57), blood pressure (55,56), mortality (56), and quality of life (54,56).

Intervention characteristics and statistically significant findings

Intervention technologies ranged from telephone outreach, internet-based, SMS messaging, and video conferencing. Some interventions included a technology component and human interaction in the form of nurses, community health workers, peer facilitators, or other trained health professionals (52,53,55-57). Four of the studies had statistically significant findings (52,54,56,57).

Discussion

There is a grave paucity of evidence in the telehealth literature and research studies where Indigenous peoples are concerned. This is the first review to summarize telehealth interventions focused on physical and mental health outcomes among Indigenous populations globally. Despite the inclusion of several outcomes of interest including mortality, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide, quality of life, hemoglobin A1C, cholesterol, and hypertension, systematic identification resulted in only six manuscripts. While the intent was to review studies of multiple Indigenous groups located in many countries around the world, studies from the USA, Canada, and New Zealand were the only ones that met eligibility criteria. As a result, the first key finding of this review is a need for well-designed interventions to understand whether telehealth is an efficacious and cost-effective way to increase access in Indigenous populations. In particular, very few mental health programs using telehealth have been developed and tested, even with Indigenous populations found in high-income countries such as the United States or Canada. During our review, we found a number of programs developed in the United States primarily focused on Veteran populations, however, these articles described the development or implementation without testing if they were successful in changing health outcomes. In addition, given the intersectionality of being Veterans in the United States and of an Indigenous heritage, it is unclear if these same programs would be successful in other settings.

Based on the studies that met inclusion criteria, we identified four key components of successful telehealth interventions to address mental and physical health outcomes in Indigenous populations. First, over the last few decades experts have emphasized the importance of evidence-based interventions (EBTs) accounting for a patient’s cultural contexts and values, including the integration of cultural values, application of culturally sensitive treatment methods, and consideration of social and economic context. As such, many experts have advocated for the adaptation of EBTs, defined as the systematic modification of interventions to consider the patient’s culture to better address the specific needs of a cultural group. Several meta-analyses have concluded that culturally-adapted treatments can increase treatment relevance, treatment engagement, and improve outcomes in comparison with un-adapted treatments (58-60). Indeed, culturally-adapted, behavioral and lifestyle interventions are effective at producing statistically significant changes in chronic disease health outcomes (61-63). Interestingly, less than half of the studies included cultural tailoring, and the two that did were published in 2017 (54,57). Future telehealth interventions should consider including cultural adaptation when trying to increase reach, adoption and improve outcomes among Indigenous populations. Moreover, given that only a few studies have focused on the development and evaluation of technology-enhanced, culturally modified interventions, future studies should thoroughly describe the applied systematic adaptation framework as well as the evaluation process in enough detail for others to reproduce.

Second, three of the four studies with statistically significant findings included the use of a telephone-based intervention (52,54,57). Currently, it is estimated that more than 5 billion people globally have mobile devices, with over half owning smartphones (64). In the US, 95% of adults use a cellphone and 77% own a smartphone (65). Racial/ethnic minority adults are just as likely to own a smartphone as White adults (77%) and are more likely to seek health related information online (65). Rates of cellphone and smartphone ownership are 92% and 67% for low-income level families (less than $300,000 per year) and 91% and 65% for rural populations, respectively (65). Interventions delivered via mobile devices might hold the most promise with regard to increasing reach and improving continuity of care among underserved and vulnerable populations (64). Indeed, telephone-based interventions have been found to be efficacious and cost-effective among minority populations across a myriad of chronic conditions (66,67), and a preferred method of telehealth communication among some patients in Australia (68). These findings suggest the importance of including telephone use in interventions developed to address chronic disease in this population. However, a major threat to the sustained use of telephone interventions in community settings is found in the inadequate, or total lack of, service reimbursement from most third party payors (69), which can negatively affect access and utilization. Policy discussions with payers should prioritize the value of these services and opportunities that they create to address access barriers and improve short- and long-term clinical outcomes for those who would not otherwise access services.

Third, intervention duration was identified as a key component of improving outcomes using telehealth programs. Four studies included in this review with statistically significant findings had interventions that lasted a minimum of 3 months, with intervention times lasting up to 20 months (52,54,56,57). Interventions delivered by a trained clinician or prescription facilitator lasted 3–6 months (54,57), whereas nurse-delivered interventions lasted 12–20 months (52,56). Consistent with the literature, behavioral and lifestyle interventions lasting a minimum of 8–12 weeks have been found to be most effective at improving health outcomes among adults with chronic disease (70).

Finally, health professional involvement (nurses and clinicians) was identified as an important aspect of successful interventions (52,54,56,57). These findings support existing knowledge indicating a need to increase capacity, financial and human resources in Indigenous communities. Health professionals including lay health workers, community health workers, peers, nurses, physicians, and researchers all have a role to play when promoting the health of Indigenous peoples (71,72). The importance of training and employing Indigenous health professionals should not be ignored. Individuals of Indigenous origin may be in a better position to address social and cultural factors impacting health and accessing healthcare services in this population (72-74). Telehealth may be a viable method of increasing access to indigenous providers for indigenous communities residing in areas where indigenous health facilities staffed by indigenous providers are limited.

Though we conducted a systematic review of the literature after searching multiple databases, there are noteworthy limitations of our study. First, articles were limited to those published between 1999 and 2018. It is possible that there are articles that were published prior to 1999 that may add to the comprehensiveness of this review, however, given the vast majority of telehealth work was conducted in the past two decades we believe the search procedures captured all relevant published literature. Second, we limited inclusion to studies published in English. This was an aspect of feasibility in completing the review, however, it is possible that studies were published in other languages. Third, we chose to review only interventions published in the peer reviewed literature. It is possible there are telehealth programs that were developed as part of state or national initiatives, and results presented in reports that cannot be searched through databases. As we were most interested in programs that were empirically tested we believe the peer reviewed literature was an appropriate requirement, however, other tested programs may exist that were not found during our search process.

Conclusions

In conclusion, there is a paucity of evidence on the use of telehealth programs to increase access to chronic disease programs in Indigenous populations. This review highlights the importance of culturally tailoring programs despite the modality in which they are delivered, and based on the findings of this review recommends telephone-based delivery facilitated by a trained health professional. These findings are consistent with the telehealth literature demonstrating that telephone as an intervention modality has been found effective across populations in managing chronic disease (75-77), however additional research is needed to further explore the impact of various modalities for Indigenous populations. Multiple factors should be considered when developing and identifying successful interventions to address the need of Indigenous peoples, including ensuring adequate intensity and utilization of technology and interaction with trained health professionals. Telehealth has great promise for meeting the health needs of highly marginalized Indigenous populations around the world, however, at this point more research is needed to understand how best to structure and deliver these programs for maximum effect.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Effort partially supported by NIH/NIDDK (K24DK093699, R01DK120861, R01DK118038, PI: Egede), NIH/NIMHD (R01MD013826, PI: Egede/Walker), ADA (1-19-JDF-075, PI: Walker).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2019.12.03). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bartlett JG, Madariaga-Vignudo L, O’Neil JD, et al. Identifying Indigenous peoples for health research in a global context: a review of perspectives and challenges. Int J Circumpolar Health 2007;66:287-307. 10.3402/ijch.v66i4.18270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subramanian SV, Smith GD, Subramanyam M. Indigenous health and socioeconomic status in India. PloS Med 2006;3:e421. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Bank. Indigenous peoples. Washington, DC, 2019, Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples

- 4.United Nations Development Program. Ten things to know about Indigenous peoples, 2019, Available online: https://stories.undp.org/10-things-we-all-should-know-about-indigenous-people

- 5.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Indigenous peoples: Health. 2019, Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/mandated-areas1/health.html

- 6.Bollyky TJ, Templin T, Cohen M, et al. Lower-income countries that face the most rapid shift in noncommunicable disease burden are also the least prepared. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:1866-75. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Dawson AZ, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, prediabetes, and obesity in the Indigenous Kuna population of Panamá. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2019;6:743-51. 10.1007/s40615-019-00573-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penm E. Cardiovascular disease and its associated risk factors in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2004-05. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2008;29:1-99. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009;374:65-75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kisely S, Alichniewicz KK, Black EB, et al. The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in Indigenous people of the Americas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2017;84:137-52. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaholokula JK, Antonio MC, Ing CK, et al. The effects of perceived racism on psychological distress mediated by venting and disengagement coping in Native Hawaiians. BMC Psychol 2017;5:2. 10.1186/s40359-017-0171-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham J, PAradies YC. Socio-demographic factrs and psychological distress in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian adults aged 18-64 years: analysis of national survey data. BMC Public Health 2012;12:95. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 2009;374:76-85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Access to health services, 2019, Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Access-to-Health-Services

- 15.Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care 1981;19:127-40. 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centered access to health care: conceptualizing access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:18. 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Universal health coverage and universal access. Geneva, Switzerland, 2013, Available online: https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/8/13-125450/en/

- 18.Kvedar J, Coye MJ, Everett W. Connected health: a review of technologies and strategies to improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:194-9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ralston AL, Andrews AR, III, Hope DA. Fulfilling the promise of mental health technology to reduce public health disparities: Review and research agenda. Clin Psychol 2019;26:e12277. [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Torre-Díez I, López-Coronado M, Vaca C, et al. Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness studies of telemedicine, electronic, and mobile health systems in the literature: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health 2015;21:81-5. 10.1089/tmj.2014.0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egede LE, Dismuke CE, Walker RJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of behavioral activation for depression in older adult Veterans. J Clin Psychiatry 2018. doi: . 10.4088/JCP.17m11888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acierno R, Gros DF, Ruggiero KJ, et al. Behavioral activation and therapeutic exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder: a noninferiority trial of treatment delivered in person versus home-based telehealth. Depress Anxiety 2016;33:415-23. 10.1002/da.22476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acierno R, Knapp R, Tuerk P, et al. A non-inferiority trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder: in person versus home-based telehealth. Behav Res Ther 2017;89:57-65. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brazionis L, Jenkins A, Keech A, et al. An evaluation of the telehealth facilitation of diabetes and cardiovascular care in remote Australian Indigenous communities: - protocol for the telehealth eye and associated medical services network [TEAMSnet] project, a pre-post study design. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:13. 10.1186/s12913-016-1967-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson TM, Soltis K, Albia CM, et al. Providers’ perspectives regarding the development of a web-based depression intervention for Latina(o) youth. Psychol Serv 2015;12:37-48. 10.1037/a0037686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraser S, Mackean T, Grant J, et al. Use of telehealth for health care of Indigenous peoples with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Rural Remote Health 2017;17:4205. 10.22605/RRH4205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carson KV, Brinn MP, Peters M, et al. Interventions for smoking cessation in Indigenous populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;1:CD009046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carson KV, Brinn MP, Labiszewski NA, et al. Interventions for tobacco use prevention in Indigenous youth (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD009325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Reilly R, Evans K, Gomersall J, et al. Effectiveness, cost effectiveness, acceptability and implementation barriers/enablers of chronic kidney disease management programs for Indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand and Canada: a systematic review of mixed evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:119. 10.1186/s12913-016-1363-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan K, Lai NM. Telemedicine for the support of parents of high-risk newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;6:CD006818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speyer R, Denman D, Wilkes-Gillan S, et al. Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med 2018;50:225-35. 10.2340/16501977-2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladhani M, Craig JC, Irving M, et al. Obesity and the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017;32:439-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollok J, van Agteren JEM, Carson-Chahhoud KV. Pharmacological interventions for the treatment of depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;12:CD012346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students. JAMA 2016;316:2214-36. 10.1001/jama.2016.17324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Wu X, Lai W, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017173. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amos T, Stein DJ, Ipser JC. Pharmacological interventions for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;7:CD006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sin J, Spain D, Furuta M, et al. Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD011464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2018;175:150-8. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter G, Milner A, McGill K, et al. Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: systematic review and meta-analysis of positive predictive values for risk scales. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:387-95. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.182717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arguedas JA, Perez MI, Wright JM. Treatment blood pressure targets for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD004349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroeder K, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. Interventions for improving adherence to treatment in patients with high blood pressure in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;3:CD004804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens SL, Wood S, Koshiaris C, et al. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;354:i4098. 10.1136/bmj.i4098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cavero-Redondo I, Peleteiro B, Alvarez-Bueno C, et al. Glycated haemoglobin A1c as a risk factor of cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015949. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karimian N, Niculiseanu P, Amar-Zifkin A, et al. Association of elevated pre-operative hemoglobin A1c and post-operative complications in non-diabetic patients: a systematic review. World J Surg 2018;42:61-72. 10.1007/s00268-017-4106-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD004022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Dong Y, Qi X, et al. Cholesterol levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke 2013;44:1833-9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters SAE, Singhateh Y, Mackay D, et al. Total cholesterol as a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2016;248:123-31. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galway K, Black A, Cantwell M, et al. Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and emotional wellbeing for recently diagnosed cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD007064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trevisol DJ, Moreira LB, Kerkhoff A, et al. Health-related quality of life and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Hypertens 2011;29:179-88. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328340d76f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le J, Dorstyn DS, Mpfou E, et al. Health-related quality of life in coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis mapped against the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Qual Life Res 2018;27:2491-503. 10.1007/s11136-018-1885-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fischer HH, Eisert SL, Everhart RM, et al. Nurse-run, telephone-based outreach to improve lipids in people with diabetes. Am J Manag Care 2012;18:77-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lorig K, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, et al. Online diabetes self-management program. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1275-81. 10.2337/dc09-2153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whealin JM, Yoneda AC, Nelson D, et al. A culturally adapted family intervention for rural Pacific Island Veterans with PTSD. Psychol Serv 2017;14:295-306. 10.1037/ser0000186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tobe SW, Yeates K, Campbell NRC, et al. Diagnosing in Indigenous Canadians (DREAM-GLOBAL): a randomized controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of short message service messaging for management of hypertension: man results. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019;21:29-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venter A, Burns R, Hefford M, et al. Results of a telehealth-enabled chronic care management service to support people with long-term conditions at home. J Telemed Telecare 2012;18:172-5. 10.1258/jtt.2012.SFT112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams M, Cairns S, Simmons D, et al. Face-to-face versus telephone delivery of the green prescription for Maori and New Zealand Europeans with type-2 diabetes mellitus: influence on participation and health outcomes. N Z Med J 2017;130:71-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benish SG, Quintana S, Wampold BE. Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: a direct-comparison meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol 2011;58:279-89. 10.1037/a0023626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy 2006;43:531-48. 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith TB, Domenech Rodríguez M, Bernal G. Culture. J Clin Psychol 2011;67:166-75. 10.1002/jclp.20757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barrera M, Jr, Castro FG, Strycker LA, et al. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81:196-205. 10.1037/a0027085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nierkens V, Hartman MA, Nicolaou M, et al. Effectiveness of cultural adaptations of interventions aimed at smoking cessation, diet, and/or physical activity in ethnic minorities. A systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e73373. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kreuter MW, Sugg-Skinner C, Holt CL, et al. Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African American women in urban public health centers. Prev Med 2005;41:53-62. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor K, Silver L. Smartphone ownership is growing rapidly around the world, but not always equally. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/02/05/smartphone-ownership-is-growing-rapidly-around-the-world-but-not-always-equally/

- 65.Pew Research Center. Mobile fact sheet. Available online: https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 66.Williams EM, Hyer JM, Viswanathan R, et al. Peer-to-peer mentoring for African American women with lupus: a feasibility pilot. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70:908-17. 10.1002/acr.23412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Egede LE, Williams JS, Voronca DC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of technology-assisted case management in low income adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2017;19:476-82. 10.1089/dia.2017.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bonner A, Gillespie K, Campbell KL, et al. Evaluating the prevalence and opportunity for technology use in chronic kidney disease patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2018;19:28. 10.1186/s12882-018-0830-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Institute of Medicine. The role of telehealth in an evolving health care environment: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2012. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207146/ [PubMed]

- 70.Looney SM, Raynor HA. Behavioral lifestyle intervention in the treatment of obesity. Health Serv Insights 2013;6:15-31. 10.4137/HSI.S10474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Macaulay AC. Improving aboriginal health. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:334-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mason J. Review of Australian government health workforce programs. Commonwealth of Australia 2013.

- 73.Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, et al. Access to primary health care. Services for Indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:163. 10.1186/s12939-016-0450-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ware VA. Improving the accessibility of health services in urban and regional settings for Indigenous people. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chamany S, Walker EA, Schechter CB, et al. Telephone intervention to improve diabetes control: a randomized trial in the New York City A1c Registry. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:832-41. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Avery G, Cook D, Talens S. The impact of a telephone-based chronic disease management program on medical expenditures. Population health management. 2016;19:156-62. 10.1089/pop.2015.0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thom DH, Ghorob A, Hessler D, et al. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:137-44. 10.1370/afm.1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]