Abstract

Background

Coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) is a potential cause of infarction. During the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), home isolation and activity reduction can lead to hypercoagulability. Here, we report a case of sudden acute myocardial infarction caused by large CAA during the home isolation.

Case presentation

During the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),a 16-year-old man with no cardiac history was admitted to CCU of Tang du hospital because of severe chest pain for 8 h. The patient reached the hospital its own, his electrocardiogram showed typical features of anterior wall infarction, echocardiography was performed and revealed local anterior wall dysfunction, but left ventricle ejection fraction was normal, initial high-sensitivity troponin level was 7.51 ng/mL (<1.0 ng/mL). The patient received loading dose of aspirin and clopidogrel bisulfate and a total occlusion of the LAD was observed in the emergency coronary angiography (CAG). After repeated aspiration of the thrombus, TIMI blood flow reached level 3. Coronary artery aneurysm was visualized in the last angiography. No stent was implanted. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was performed and the diagnosis of coronary artery aneurysm was further confirmed. The patient was discharged with a better health condition.

Conclusions

Coronary artery aneurysm is a potential reason of infarction, CAG and IVUS are valuable tools in diagnosis in such cases, during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), home isolation and activity reduction can lead to hypercoagulability, and activities at home should be increased in the high-risk patients.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Coronary artery aneurysm, IVUS

Background

Coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) is a potential reason of infarction. During the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), home isolation and activity reduction can lead to hypercoagulability. Here, we report a case of large CAA complicated with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in a 16-year-old man during the home isolation.

Case presentation

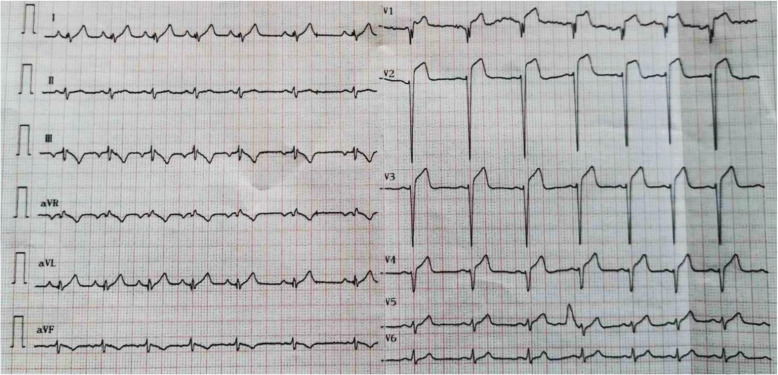

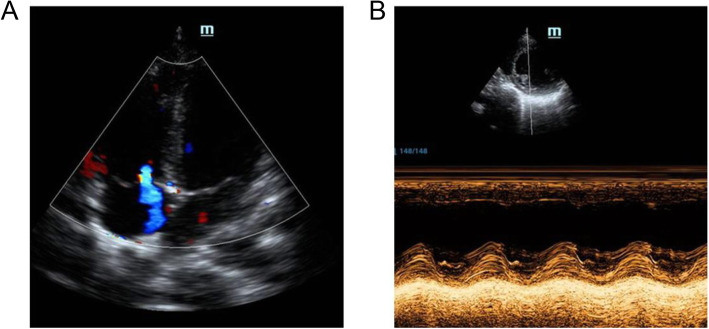

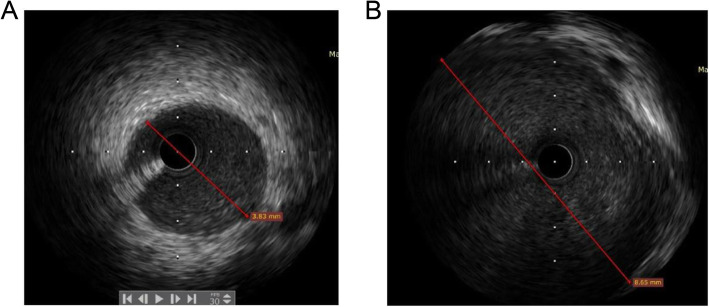

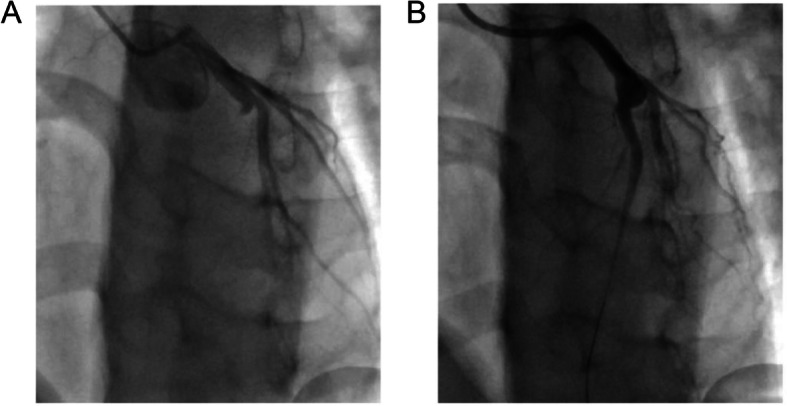

During the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a 16-year-old man with no cardiac history was admitted to CCU of Tang du hospital because of severe chest pain for 8 h. the patient reached the hospital its own. His cardiovascular examination revealed an initial blood pressure of 110/65 mmHg, heart rate of 95b.p.m.,body mass index (BMI)15.5 kg/m2, his electrocardiogram showed typical features of anterior wall infarction (Fig. 1) with a raised initial high-sensitivity troponin level which was 7.51 ng/mL (<1.0 ng/mL). On auscultation, his chest was clear and heart sounds were normal. In echocardiography, we found local anterior wall dysfunction, but left ventricle ejection fraction was normal (Fig. 2a, b). He had neither a history of hypertension, diabetes, smoking nor a family history of coronary heart disease. He had neither cold nor fever recently., and he denied the possibility of a past exposure to COVID-19. No medication was taken before admission. The patient received loading dose of aspirin and clopidogrel bisulfate, angiography that was performed immediately after transfer to the hospital, a total occlusion of the LAD from the proximal segment (Fig. 3a) was observed in the emergency coronary angiography (CAG). Right coronary artery and left circumflex artery were normal. A guidewire was successfully advanced across the occlusive lesion and a large fresh red thrombus was removed by aspiration catheter. After repeated aspiration of the thrombus and intra-coronary injection of tirofiban and urokinase, TIMI blood flow reached to level 3. Coronary artery aneurysm was visualized in the last angiography (Fig. 3b). Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was performed and further confirmed the diagnosis of coronary artery aneurysm (Fig. 4). No stent was implanted. ECG after the event showed resolution of MI pattern and evolution of infarction has been observed. After the emergency, results of laboratory assessments included normal levels of electrolytes, blood lipid and glucose, the C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 2.27 mg/L (0-3 mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 20 mm/h (0–15 mm/h), NT-proBNP was 670 pg/ml, nucleic acid testing was negative, both inflammatory marker and rheumatoid factors were normal, ANA and other autoimmune markers were negative ruling out active connective tissue disease. The chest CT scan was normal. His test result for COVID-19 was negative. A computed tomography angiography (CTA) scan 5 days after admission showed that coronary artery aneurysm in the LAD (Fig. 5). the widest segment was about 8.6 mm. The patient was discharged home 7 d later on dual anti-platelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg).

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiogram showing sinus tachycardia with ST-segment elevation on V1–5

Fig. 2.

a In transthoracic echocardiography, local anterior wall dysfunction has been observed. b M-mode echocardiography showed left ventricle ejection fraction was good

Fig. 3.

a Left coronary angiogram revealed a total occlusion of the LAD from the proximal segment; b Left coronary angiogram revealed a very large round aneurysm (arrowheads) originating from the proximal segment of the LAD

Fig. 4.

a IVUS showing normal LAD, the vessel diameter was 3.8 mm. b IVUS showing Coronary artery aneurysm, the widest segment was about 8.6 mm

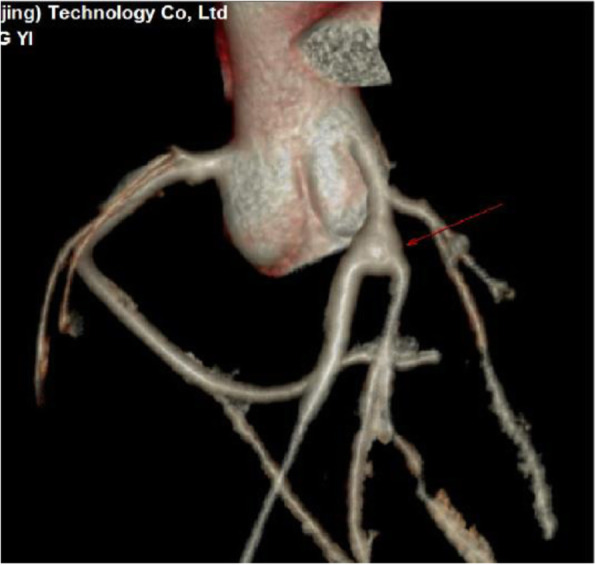

Fig. 5.

CTA showing a very large round aneurysm originating from the proximal segment of the LAD (red arrow indicating the aneurysm)

Discussion and conclusions

Coronary artery aneurysm is a potential reason of infarction. In older adults, Coronary artery aneurysm is associated with coronary atherosclerosis in more than 50% of cases. Other causes include Kawasaki’s disease (KD), Behcet’s Syndrome; Polyarteritis nodosa, Takayasu’s disease, Connective Tissue Disorders like Marfan syndrome, HIV, fungal, syphilitic Infections; use of illicit drugs like a mphetamine, cocaine [1] In our case, the patient is a 16-year-old man, in CAG, a total occlusion of the LAD was observed, but Right coronary artery and left circumflex artery were normal, and no atherosclerotic plaque was observed in IVUS. So the cause of infarction is not associated with atherosclerotic stenotic lesions. The patient and his parents denied the history of exposure to COVID-19, and his test result for COVID-19 was normal. They denied the history of Kawasaki’s disease, ANA and other autoimmune markers were negative ruling out active connective tissue disease, but maybe he had Kawasaki disease history when he was a child, but he and his parents did not know it.

The definition of coronary artery aneurysm is the internal diameter of coronary arteries dilatate > 1.5 times larger than the adjacent angiographically normal artery [2]. the diagnostic methods include CAG, IVUS and CTA. the CAG is an important diagnostic method for the coronary artery aneurysm. IVUS can not only accurately measure the diameter of aneurysm, but also distinguish between true aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm.

Coronary aneurysm was an obstructive ischemic coronary artery disease with impaired flow volume and may lead to exercise-induced myocardial ischemia [3]. The coronary flow reserve was also markedly reduced in the coronary aneurysms [4]. Computational fluid dynamics simulation has demonstrated that the hemodynamic parameters were different between coronary aneurysms and normal arteries specifically. The time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS) may be decreased and the oscillatory shear index (OSI) may be increased in aneurysms [5]. These changes could induce focal endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammation, which primes arterial regions for subsequent atherosclerosis initiation in response to hypercholesterolemia, and promote the transformation of stable plaque subtypes to unstable subtypes [6, 7]. And this hemodynamic changes in coronary aneurysms may increase blood viscosity and activates coagulation [8].

Coronary artery aneurysm is a potential cause of infarction. The treatments of CAA include medical, interventional and surgical therapy, because of there are no large clinical trials or guidelines in this subject., the treatment varies from doctor to doctor Medical treatments include antiplatelet agents, thrombolytic agents and anticoagulants [9]. In our case, we chose conservative management., dual anti-platelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg). The patient was in good condition during the 1-month follow-up. During the outbreak of COVID-19, home isolation and activity reduction can lead to hypercoagulability, infarction is more likely to happen., so activities at home should be increased in the high-risk patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CCU

Cardiac care unit

- IVUS

Intravascular ultrasound,

- CAG

Coronary angiography

- LAD

Left anterior descending

- ECG

Echocardiography

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- BMI

Body mass index

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- ANA

Antinuclear antibodies

- CTA

Computed tomography angiography

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- TAWSS

Time-averaged wall shear stress

- OSI

Oscillatory shear index

Authors’ contributions

WSM drafted the manuscript. CYL made critical revision of the manuscript. WZ, YL, and WSM performed the percutaneous coronary interventions. ZLJ contributed to data and images collection, YL provided consultation, participated in the design and coordination of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data is contained within the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the clinical details and images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yach D, Stuckler D, Brownell KD. Epidemiologic and economic consequences of the global epidemics of obesity and diabetes. Nat Med. 2006;12:62–66. doi: 10.1038/nm0106-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shridhar P, Smith T, Khalil R, Lasorda D, Chun Y. Exclusion of giant coronary artery aneurysm with covered stent combined with coil embolization of vessel outflow. Med Case Rep. 2016;2(3):1–3. doi: 10.21767/2471-8041.1000033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krüger D, Al Mokhtari NE, Wieckhorst A, Rausche T, Simon-Herrmann G, Simon R. Evidence of pathological coronary flow patterns in patients with isolated coronary artery aneurysms. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19:249–255. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3283030b4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruger D, ElMokhtari NE, Wieckhorst A, Simon-Herrmann G, Simon R. Intravascular ultrasound study and evidence of pathological coronary flow reserve in patients with isolated coronary artery aneurysms. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s00392-009-0100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noelia GG, Mathew M, McCrindle BW, Tran JS, Kahn AM, Burns JC, Marsden AL. Hemodynamic variables in aneurysms are associated with thrombotic risk in children with Kawasaki disease. Int J Cardiol. 2019;22:1515–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwak BR, Back M, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Caligiuri G, Daemen MJ, Davies PF, Hoefer IE, Holvoet P, Jo H, Krams R, Lehoux S, Monaco C, Steffens S, Virmani R, Weber C, Wentzel JJ, Evans PC. Biomechanical factors in atherosclerosis: mechanisms and clinical implications. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3013–3020. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown AJ, Teng Z, Evans PC, Gillard JH, Samady H, Bennett MR. Role of biomechanical forces in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13:210–220. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi T, Kataoka Y, Noguchi T, Shibata T, Nakashima T, Kawakami S, Nakao K, Fujino M, Nagai T, Kanaya T, Tahara Y, Asaumi Y, Tsuda E, Nakai M, Nishimura K, Anzai T, Kusano K, Shimokawa H, Goto Y, Yasuda S. Coronary artery Ectasia predicts future cardiac events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:2350–2355. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Befeler B, Aranda MJ, Embi A, Mullin FL, El-Sherif N, Lazzara R. Coronary artery aneurysms: study of the etiology, clinical course and effect on left ventricular function and prognosis. Am J Med. 1977;62:597–607. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is contained within the manuscript.