Abstract

Background: Operating room professionals are exposed to high levels of stress and burnout. Besides affecting the individual, it can compromise patient safety and quality of care as well. Meditation practice is getting recognized for its ability to improve wellness among various populations, including healthcare providers.

Methods: Baseline stress levels of perioperative healthcare providers were measured via an online survey using a Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire. An in-person meditation workshop was demonstrated during surgical grand rounds and an international anesthesia conference using a 15-minute guided Isha Kriya meditation. The participants were then surveyed for mood changes before and after meditation using a Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire.

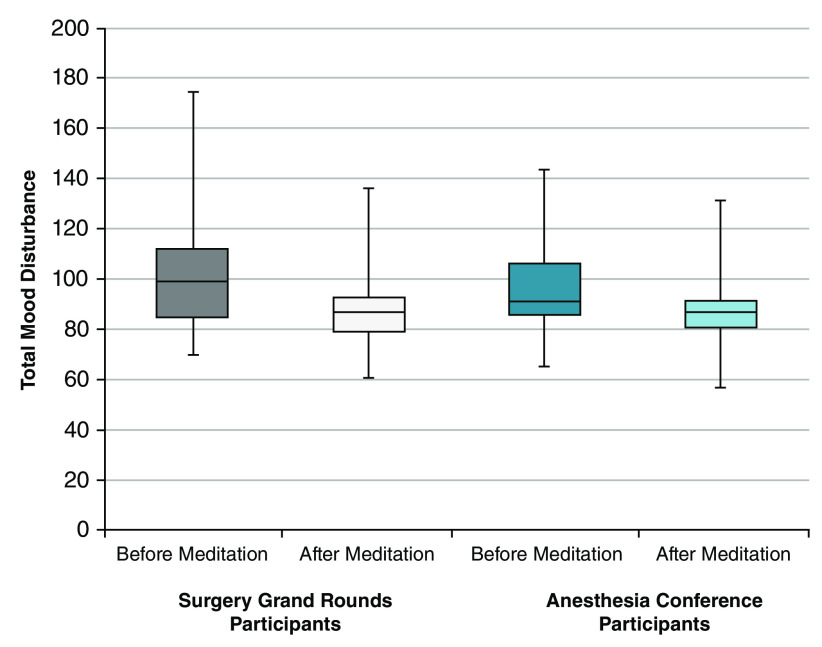

Results: Surgeons and anesthesiologists were found to have higher median (interquartile range) Perceived Stress Scores as compared to nurses respectively (17 [12, 20] and 17 [12, 21] vs 14 [9, 19]; P = 0.01). Total mood disturbances were found to be significantly reduced after meditation in both the surgical grand rounds (pre-meditation median [IQR] 99 [85, 112] vs 87 [80, 93] post-meditation; P < 0.0001) and anesthesia conference cohorts (pre-meditation 92 [86, 106] vs 87 [81, 92] post-meditation; P < 0.0001).

Conclusions: Isha Kriya, a guided meditation, is easy to learn and takes less than 15 minutes to complete. This meditation technique improves mood changes and negative emotions among operating room professionals and could be used as a potential tool for improving wellness.

Keywords: meditation, stress, burnout, healthcare providers, anesthesia, surgery, operating room professionals

Introduction

Wellness is not just merely an absence of a disease, it encompasses physical, mental and social well-being 1. Stress associated with work, when left unaddressed, results in burnout. Around 30–60% of healthcare providers suffer from burnout and 400 physicians die by suicide every year 2. Work environment (work overload, insufficient reward), demographic variables (early career, lack of life partner or children), and personality traits (low confidence, overachieving, impatience, perfectionist) can contribute to stress and burnout 2.

Operating rooms are highly stressful environments involving complex, respectful, and essential interactions. Surgeons, anesthesiologists and nurses can develop health problems, social issues and substance use due to stress and burnout 3, 4. Employee disengagement is estimated to cost around 450 billion USD per year, and illness-related absences are common in burned out employees 5. Despite the critical need, no effective treatment options and well-described organizational approach exists for wellness among healthcare providers 6.

World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the need for workplace health interventions aiming to improve the wellness of employees 1. However, there is a lack of high-quality trials with simple and potentially effective interventions. Isha Kriya (IK) is a 15-minute, simple guided meditation tool employing thought, breathing, and awareness 5. We hypothesized that operating room professionals experience significant stress, and IK meditation would decrease their mood disturbances. In this pilot study, we sought to measure the a) stress levels among surgeons, nurses and anesthesiologists, and b) mood changes following a one-time IK meditation session.

Methods

Ethical considerations and reporting

This prospective interventional pilot study was conducted after Institutional Review Board approval (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, US. Protocols 2017P000657, 2018P000200, 2018P000585) with an electronic consent. Written informed consent was waived by our IRB. This manuscript adheres to the applicable Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for pilot and feasibility trials 7, 8.

Stress assessment

An online survey with Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire (available as extended data 9) was used to assess the stress levels among the operating room professionals at a single academic teaching hospital. This 10-item questionnaire measures an individual’s feeling about a stress factor over the past 30 days 10, 11. Anesthesiologists were surveyed in February 2018, and other operating room professionals including nurses and surgeons were surveyed in August 2018. The survey was conducted anonymously and willing participants could complete using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap 8.10.6; Vanderbilt University) with three weekly automatic reminders for incomplete surveys.

Meditation and evaluation

Following this survey, a 15-minute guided IK meditation (guide available as extended data 12) was demonstrated during a) surgical grand rounds at our institution (September 2018) and b) the Annual Meeting of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) wellness workshop (October 2018). The Profile of Mood States (POMS) [Revised Version 15.2] 13 questionnaire (available as extended data 14) was used to assess the mood changes before and after meditation. POMS is a psychological rating scale assessing transient and distinct mood states. In both the settings, willing participants could complete the survey anonymously either on paper or by using a link directly in REDCap.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were presented as median (interquartile range) or frequencies and proportions. Normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between cohorts were assessed using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney or chi-square test, as appropriate. With small cell sizes, Fisher’s Exact test was used. No sample size calculations were done in this pilot trial. All willing members in the specific settings were included in the study.

Our primary outcome, the mood changes with meditation, was assessed using separate Wilcoxon signed rank sum tests. Bonferroni correction was used to keep the familywise error rate at 0.05. P values were considered statistically significant when < 0.025 (0.05 / 2 tests). Analysis of secondary outcomes including positive and negative subscales with their respective components were deemed exploratory and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

PSS Survey

Table 1 displays the demographic information from the PSS survey. Of the total 910 participants, 362 (39.8%) completed the survey, including 101 (27.9%) anesthesiologists, 61 surgeons (16.9%) and 151 (41.7%) nurses. Respondents were primarily female (65.8%), white (73.1%), non-Hispanic/Latino (87.6%) and 30–44 years old (38%). One-third (32.8%) of respondents had more than 15 years of work experience. Nurses reported more years of work experience than the other respondents (47.7% vs 23% and 22.2%; P < 0.0001). Raw data from this survey are available on Figshare 15.

Table 1. Demographics of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Survey Respondents.

| Demographics | Surgeons

N = 61 |

Anesthesiologists

N = 101 |

Nurses

N = 151 |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.22 | |||

| 18–29 | 11 (18.33) | 15 (15.15) | 21 (13.91) | |

| 30–44 | 27 (45.00) | 47 (47.47) | 48 (31.79) | |

| 45–54 | 9 (15.00) | 21 (21.21) | 33 (21.85) | |

| 55–64 | 9 (15.00) | 12 (12.12) | 38 (25.17) | |

| 65 & older | 3 (5.00) | 3 (3.03) | 9 (5.96) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 1 (1.67) | 1 (1.01) | 2 (1.32) | |

| Female Gender | 23 (37.70) | 46 (46.94) | 136 (90.07) | <0.0001 |

| Race | 0.004 | |||

| White | 41 (68.33) | 66 (67.35) | 130 (86.09) | |

| Black or African American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.66) | |

| Asian | 12 (20.00) | 15 (15.31) | 7 (4.64) | |

| Multi-Racial | 2 (2.04) | 2 (2.04) | 2 (1.32) | |

| Other | 7 (7.14) | 7 (7.14) | 2 (1.32) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 8 (8.16) | 8 (8.16) | 9 (5.96) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.03 | |||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 53 (91.38) | 79 (83.16) | 134 (91.16) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (5.17) | 4 (4.21) | 0 (0) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 (3.45) | 12 (12.63) | 13 (8.84) | |

| Clinical Role | 0.98 | |||

| Attending | 32 (56.14) | 46 (49.46) | --- | |

| Fellow | 3 (5.26) | 5 (5.38) | --- | |

| Resident | 22 (38.60) | 28 (30.11) | --- | |

| Nurse | 0 (0) | 10 (10.75) | --- | |

| Researcher | 0 (0) | 1 (1.08) | --- | |

| I prefer not to answer | 0 (0) | 3 (3.23) | --- | |

| Years of Service | <0.0001 | |||

| 0–1 | 6 (9.84) | 18 (18.18) | 7 (4.64) | |

| 2–5 | 19 (31.15) | 33 (33.33) | 25 (16.56) | |

| 5–10 | 14 (22.95) | 11 (11.11) | 17 (11.26) | |

| 10–15 | 8 (13.11) | 11 (11.11) | 28 (18.54) | |

| > 15 | 14 (22.95) | 22 (22.22) | 72 (47.68) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 0 (0) | 4 (4.04) | 2 (1.32) | |

| Perceived Stress Score | 17.0 (12.0, 20.0) | 17.0 (11.5, 21.0) | 13.5 (9.0, 19.0) | 0.01 |

Values are presented as number (%) or median (quartile 1, quartile 3).

Surgeons and anesthesiologists had higher median [IQR] perceived stress scores than nurses (17 [12, 20] and 17 [11.5, 21] vs 13.5 [9, 19]; P = 0.01). Table 2 compares the perceived stress scores of based on the clinical role. Surgery residents (17 [15, 19]) and fellows (18.5 [14, 20]) had higher stress scores than attending physicians (17.5 [10, 20]), although this difference was not significant ( P = 0.12). A similar relationship was observed among residents and fellows in anesthesia ( P = 0.71).

Table 2. Perceived Stress Scores Among Surgeons and Anesthesiologists Stratified by Clinical Role.

| Clinical Role | Attending | Resident | Fellow | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeons | 17.5 (10.0, 20.0) | 17.0 (15.0, 19.0) | 18.5 (14.0, 20.0) | 0.12 |

| Anesthesiologists | 16.0 (11.0, 18.0) | 20.0 (14.0, 24.0) | 20.0 (13.0, 24.0) | 0.71 |

*Values are presented as median (quartile 1, quartile 3).

POMS survey

Demographic data for participants who completed the POMS survey were listed in Table 3. A total of 50 surgeons participated in IK meditation during surgical grand rounds and 28 (56%) completed the POMS questionnaire. Raw data from this questionnaire are available on Fighsare 16. Similarly, 52 anesthesiologists attending the ASA conference participated in the meditation workshop and 44 (85%) completed the questionnaire. Respondents from the anesthesia conference were significantly older, more likely to be attending physicians and had more experience as compared to those from surgical grand rounds (all P values < 0.0001). A significantly higher number of anesthesia conference respondents reported meditating ( P = 0.03) or performing aerobic exercise ( P = 0.002) three to four times a week as compared to the surgical respondents at our institution. Only 7% of surgical and 27% of anesthesia conference respondents practiced meditation routinely.

Table 3. Demographic Data of Respondents Who Completed the Profile of Moods Survey (POMS).

| Demographics | Surgical Grand

Rounds N = 28 |

Anesthesia

Conference N = 44 |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | <0.0001 | ||

| 18–40 | 22 (78.57) | 11 (25.00) | |

| 40–60 | 3 (10.71) | 18 (40.91) | |

| ≥ 60 | 2 (7.14) | 15 (34.09) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 1 (3.57) | 0 (0) | |

| Female Gender | 11 (39.29) | 26 (59.09) | 0.10 |

| Role | <0.0001 | ||

| Attending | 4 (14.29) | 34 (77.27) | |

| Fellow | 4 (14.29) | 0 (0) | |

| Resident | 13 (46.43) | 3 (6.82) | |

| Other | 6 (21.43) | 6 (13.64) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 1 (3.57) | 1 (2.27) | |

| Years of Service | <0.0001 | ||

| 0–5 | 22 (78.57) | 8 (18.18) | |

| 5–10 | 0 (0) | 4 (9.09) | |

| 10–20 | 2 (7.14) | 11 (25.00) | |

| ≥ 20 | 1 (3.57) | 21 (47.73) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 3 (10.71) | 0 (0) | |

| Meditated 3–4 Times a Week Before | 2 (7.14) | 12 (27.27) | 0.03 |

| Aerobic Exercises 3–4 Times a Week | 8 (28.57) | 29 (65.91) | 0.002 |

Values are presented as number (%).

Mood changes with IK meditation

Mood changes before and after IK meditation during surgical grand rounds and anesthesia conference were presented in Table 4 and Figure 1. In surgical grand rounds, total mood disturbances (TMD) were significantly reduced after meditation (pre vs post meditation: median [IQR] 99 [85, 112] vs 87 [80, 93]; P < 0.0001). A similar reduction was observed with all negative subscales (19 [7, 32] vs 7 [2, 31]; P < 0.0001), including tension, anger, fatigue, confusion and depression (all statistically significant; P-values < 0.003). No significant change was observed for positive subscales (22 [17, 26] vs 22 [18, 27]; P = 0.94), including esteem-related affect and vigor.

Table 4. Outcomes of Respondents Who Completed the Profile of Moods Survey (POMS) Before and After Isha Kriya Meditation.

| Outcomes | Surgical Grand Rounds N = 28 | Anesthesia Conference N = 44 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before

Meditation |

After

Meditation |

P-value | Before

Meditation |

After

Meditation |

P-value | |

| Total Mood Disturbance | 99 (85, 112) | 87 (80, 93) | <0.0001 * | 92 (86, 106) | 87 (81, 92) | <0.0001 * |

| Individual Subscales | ||||||

| Negative Subscales | 19 (7, 32) | 7 (2, 13) | <0.0001 * | 14 (11, 23) | 4 (1, 9) | <0.0001 * |

| Tension | 5 (2, 8) | 1 (0, 3) | <0.0001 * | 4 (1, 6) | 0 (0, 3) | <0.0001 * |

| Anger | 1 (0, 5) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.003 * | 1.5 (0, 3) | 0 (0, 0) | <0.0001 * |

| Fatigue | 6 (2, 8) | 3 (1, 5) | 0.0001 * | 4 (3, 7) | 4 (1, 9) | <0.0001 * |

| Depression | 2 (0, 5) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.0003 * | 2 (0, 4) | 0 (0, 0) | <0.0001 * |

| Confusion | 4 (2, 6) | 1 (0, 3) | <0.0001 * | 4 (2, 6) | 1 (0, 2) | <0.0001 * |

| Positive Subscales | 22 (17, 26) | 22 (18, 27) | 0.94 | 22 (17, 28) | 20 (15, 24) | 0.15 |

| Esteem Related Affect | 15 (13, 18) | 16 (12, 17) | 0.99 | 15 (12, 17) | 15 (12, 17) | 0.69 |

| Vigor | 6.5 (6, 9) | 7 (5, 9) | 0.98 | 7 (4, 11) | 6 (2, 8) | 0.03 |

Values are presented as median (quartile 1, quartile 3). Note: In order to account for multiple testing of our primary outcome, total mood disturbance, p-values for the primary outcome are significant if the p-value is < 0.025 (= 0.05 / 2). All other secondary outcomes including individual subscales are considered exploratory, therefore p-values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant. Significant values are denoted as * in the table above.

Figure 1. Total mood disturbances before and after Isha Kriya meditation.

Each of the boxplots represents the total mood disturbance before and after a single guided meditation session (Isha Kriya) among all respondents, including those at both the surgical grand rounds and the anesthesia conference.

Consistent with the results from surgical respondents, TMD during anesthesia conference significantly reduced after meditation (92 [86, 106] vs 87 [81, 92]; P < 0.0001). Negative subscales showed a significant reduction after meditation (14 [11, 23] vs 4 [1, 9]; P < 0.0001). Individual subscales such as tension, anger, fatigue, confusion, and depression were also reduced significantly (all P values < 0.0001). No significant changes were seen for positive subscales.

Discussion

This study showed two important findings: a) high levels of stress among operating room professionals and b) one-time 15-minute guided IK meditation significantly reduced TMD, including negative subscales such as tension, anger, fatigue, depression and confusion.

Stress levels among physicians in this study were higher than those levels reported in the general population 10. In a 2011 national survey, physicians had higher levels of stress and burnout than any other working population in the United States 17. Excessive workload, administrative burdens, decreased meaning from work, and difficulty in managing personal life were some of the prominent reasons suggesting a significant workplace contribution for burnout.

The higher stress levels found among surgical residents and fellows in training than attending physicians were consistent with a nationwide survey from France that showed a 40% incidence of severe burnout in surgery residents 18. Those authors insisted on further research and interventions to prevent any devastating effects among residents. In this study, we explored the effectiveness of guided IK meditation and found a significant improvement in mood changes.

Mindfulness and meditation techniques were utilized for the wellness of healthcare providers 19. The estimated cost of burnout among physicians in Canada was found as $213 million 20. Harvard business review reports that Johnson & Johnson saved around $250 million on health care costs by implementing in-house wellness programs 21. In this study, after a 15-minute, simple, guided IK meditation, participants reported a reduction in mood disturbances. It is encouraging to compare these results with previous research where healthcare professionals reported widespread benefits after meditation programs 19. However, the participants in those studies were from various parts of healthcare system, where the levels of stress and burnout could be different.

The operating room environment is unique, and conflicts may arise due to a difference in information, opinion, experience and interests. IK meditation could be used as a simple tool to de-identify thoughts and bodily sensations.

Our study has several limitations. Although this study utilized anonymous surveys, participation bias becomes unavoidable. The participation was kept entirely voluntary, and self-selection bias could limit extrapolation of the observed results. Furthermore, our sample size was relatively small, which may have implications in the generalization of these results. To our knowledge, this study was the first to use a simple, one-time, 15-minute guided IK meditation for improving wellness among operating room professionals. We used a validated PSS and POMS questionnaire to observe the perceived stress level as well as mood changes after meditation.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that IK, a 15-minute guided meditation technique, could improve mood changes among operating room professionals. Stress levels observed among physicians emphasize the need for strategies aiming to improve wellness. Moreover, randomized trials and research observing long term effect of meditation practice compliance and positive provider wellbeing that will eventually translate to better patient outcomes.

Data availability

Underlying data

Figshare: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Survey.xlsx. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7808723 15.

Figshare: Profile of Mood States (POMS) survey before and after Isha Kriya meditation.xlsx. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7808729 16.

Extended data

Figshare: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) survey questionnaire. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7808747 9.

Figshare: Instructions and details of IshaKriya meditation session. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7808741 12.

Figshare: Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7808756 14.

Reporting guidelines

Figshare: CONSORT checklist, extension for Pilot and Feasibility Trials for study “The effect of a one-time 15-minute guided meditation (Isha Kriya) on stress and mood disturbances among operating room professionals: a prospective interventional pilot study”. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7808735 8.

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Anon: Healthy workplaces: a WHO global model for action. WHO. [Accessed October 28, 2018]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dzau VJ, Kirch DG, Nasca TJ: WHO | Healthy workplaces: a WHO global model for action. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):312–314. 10.1056/NEJMp1715127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, et al. : Distress and career satisfaction among 14 surgical specialties, comparing academic and private practice settings. Ann Surg. 2011;254(4):558–568. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318230097e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hyman SA, Shotwell MS, Michaels DR, et al. : A Survey Evaluating Burnout, Health Status, Depression, Reported Alcohol and Substance Use, and Social Support of Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(6):2009–2018. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anon: Isha Kriya Yoga - Free Online Guided Meditation Video By Sadhguru. [Accessed November 11, 2018]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romani M, Ashkar K: Burnout among physicians. Libyan J Med. 2014;9: 23556. 10.3402/ljm.v9.23556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. : CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. 10.1136/bmj.i5239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rangasamy V: CONSORT checklist. figshare.Paper.2019. 10.6084/m9.figshare.7808735.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rangasamy V: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) survey questionnaire. figshare. 2019. Paper. 10.6084/m9.figshare.7808747.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taylor JM: Psychometric analysis of the Ten-Item Perceived Stress Scale. Psychol Assess. 2015;27(1):90–101. 10.1037/a0038100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rangasamy V: Instructions and details of IshaKriya meditation session. figshare.Paper.2019. 10.6084/m9.figshare.7808741.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grove JR, Prapavessis H: Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of an abbreviated profile of mood states. Int J Sport Psychol. 1992;23(2):93–109. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rangasamy V: Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire. figshare. 2019. Paper. 10.6084/m9.figshare.7808756.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rangasamy V: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Survey.xlsx. figshare.Dataset.2019. 10.6084/m9.figshare.7808723.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rangasamy V: Profile of Mood States (POMS) survey before and after Isha Kriya meditation.xlsx. figshare.Dataset.2019. 10.6084/m9.figshare.7808729.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. : Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faivre G, Kielwasser H, Bourgeois M, et al. : Burnout syndrome in orthopaedic and trauma surgery residents in France: A nationwide survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104(8):1291–1295. 10.1016/j.otsr.2018.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lynch J, Prihodova L, Dunne PJ, et al. : Mantra meditation programme for emergency department staff: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e020685. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, et al. : An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berry LL, Mirabito AM, Baun WB: What’s the Hard Return on Employee Wellness Programs?[Accessed October 29, 2018]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]