Abstract

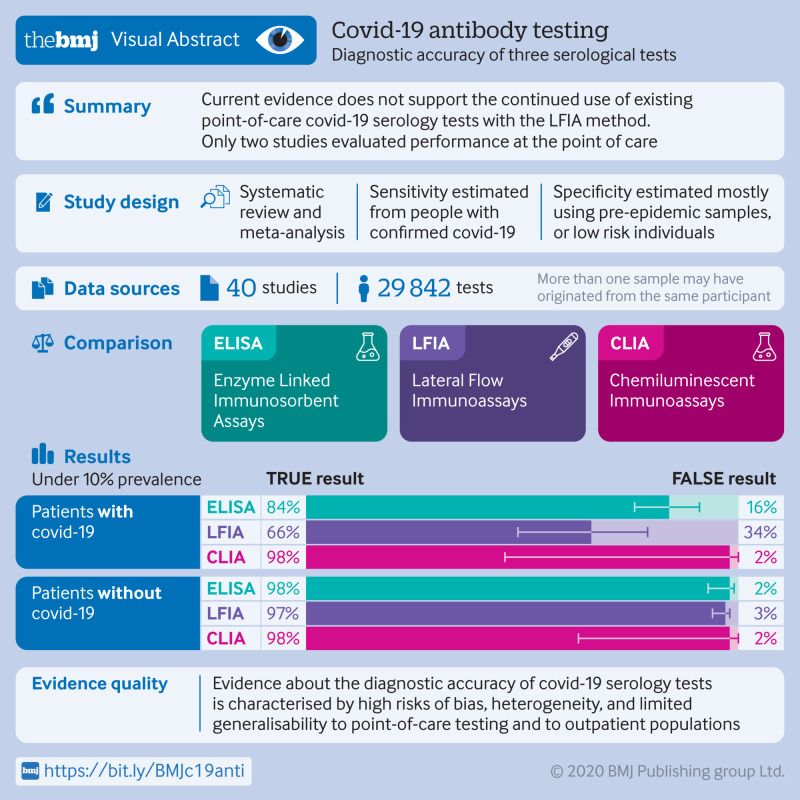

Objective

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for coronavirus disease-2019 (covid-19).

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Medline, bioRxiv, and medRxiv from 1 January to 30 April 2020, using subject headings or subheadings combined with text words for the concepts of covid-19 and serological tests for covid-19.

Eligibility criteria and data analysis

Eligible studies measured sensitivity or specificity, or both of a covid-19 serological test compared with a reference standard of viral culture or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Studies were excluded with fewer than five participants or samples. Risk of bias was assessed using quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies 2 (QUADAS-2). Pooled sensitivity and specificity were estimated using random effects bivariate meta-analyses.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was overall sensitivity and specificity, stratified by method of serological testing (enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), lateral flow immunoassays (LFIAs), or chemiluminescent immunoassays (CLIAs)) and immunoglobulin class (IgG, IgM, or both). Secondary outcomes were stratum specific sensitivity and specificity within subgroups defined by study or participant characteristics, including time since symptom onset.

Results

5016 references were identified and 40 studies included. 49 risk of bias assessments were carried out (one for each population and method evaluated). High risk of patient selection bias was found in 98% (48/49) of assessments and high or unclear risk of bias from performance or interpretation of the serological test in 73% (36/49). Only 10% (4/40) of studies included outpatients. Only two studies evaluated tests at the point of care. For each method of testing, pooled sensitivity and specificity were not associated with the immunoglobulin class measured. The pooled sensitivity of ELISAs measuring IgG or IgM was 84.3% (95% confidence interval 75.6% to 90.9%), of LFIAs was 66.0% (49.3% to 79.3%), and of CLIAs was 97.8% (46.2% to 100%). In all analyses, pooled sensitivity was lower for LFIAs, the potential point-of-care method. Pooled specificities ranged from 96.6% to 99.7%. Of the samples used for estimating specificity, 83% (10 465/12 547) were from populations tested before the epidemic or not suspected of having covid-19. Among LFIAs, pooled sensitivity of commercial kits (65.0%, 49.0% to 78.2%) was lower than that of non-commercial tests (88.2%, 83.6% to 91.3%). Heterogeneity was seen in all analyses. Sensitivity was higher at least three weeks after symptom onset (ranging from 69.9% to 98.9%) compared with within the first week (from 13.4% to 50.3%).

Conclusion

Higher quality clinical studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for covid-19 are urgently needed. Currently, available evidence does not support the continued use of existing point-of-care serological tests.

Study registration

PROSPERO CRD42020179452.

Introduction

Accurate and rapid diagnostic tests will be critical for achieving control of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19), a pandemic illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Diagnostic tests for covid-19 fall into two main categories: molecular tests that detect viral RNA, and serological tests that detect anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulins. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), a molecular test, is widely used as the reference standard for diagnosis of covid-19; however, limitations include potential false negative results,1 2 changes in diagnostic accuracy over the disease course,3 and precarious availability of test materials.4 Serological tests have generated substantial interest as an alternative or complement to RT-PCR in the diagnosis of acute infection, as some might be cheaper and easier to implement at the point of care. A clear advantage of these tests over RT-PCR is that they can identify individuals previously infected by SARS-CoV-2, even if they never underwent testing while acutely ill. As such, serological tests could be deployed as surveillance tools to better understand the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 and potentially inform individual risk of future disease.

Many serological tests for covid-19 have become available in a short period, including some marketed for use as rapid, point-of-care tests. The pace of development has, however, exceeded that of rigorous evaluation, and important uncertainty about test accuracy remains.5 We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our objectives were to evaluate the quality of the available evidence, to compare pooled sensitivities and specificities of different test methods, and to identify study, test, and patient characteristics associated with test accuracy.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Our systematic review and meta-analysis is reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines6 (see supplementary file). We searched Ovid-Medline for studies published in 2020, with no restrictions on language. Subject headings/subheadings (when applicable) combined with text words were used for the concepts of covid-19 (or SARS-CoV-2) and serological tests. The supplementary file provides the complete search strategy, run on 6 April 2020 and repeated on 30 April 2020. To identify pre-peer reviewed (preprints) studies, we searched the entire list of covid-19 preprints from medRxiv and bioRxiv (https://connect.medrxiv.org/relate/content/181) initially on 4 April 2020, and again on 28 April 2020. We also considered articles referred by colleagues or identified in references of included studies.

Eligible studies were randomised trials, cohort or case-control studies, and case series, reporting the sensitivity or specificity, or both of a serological test for covid-19. We excluded review articles, editorials, case reports, modelling or economic studies, articles with sample sizes less than five, and studies that only reported analytical sensitivity (ie, dilutional identification of detection limits).7 Three investigators (MB, GT, FAK) independently screened titles and abstracts, and two (MB, GT) independently screened full text papers. We used a sensitive screening strategy at the title or abstract level wherein selection by a single reviewer was sufficient for a study to undergo full text review. A third reviewer (FAK) resolved disagreements between reviewers at the full text stage. In the systematic review and meta-analyses, we included studies when sensitivity or specificity, or both of at least one covid-19 serological test was measured against a reference standard of viral culture or RT-PCR.

Data analysis

In our primary analysis, we estimated pooled sensitivity and specificity by method of serological test. We expected that accuracy would be associated with the immunoglobulin class being measured, as is the case for other coronaviruses.8 9 10 As such, we stratified the primary results by class of immunoglobulin detected.

One investigator (MB) extracted aggregate study level data using a piloted standardised electronic data entry form. For each study, a second reviewer (ZL or EM) verified all entered data. No duplicate data were identified. We collected information on study characteristics (location, design), study populations (age, sex, clinical severity, sources of populations used for estimating specificity), the timing of specimen collection in relation to onset of symptoms, and methodological details about index and reference tests. We categorised the tests by method: enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), lateral flow immunoassays (LFIAs), or chemiluminescent immunoassays (CLIAs). In several studies, investigators assessed the accuracy of more than one test method (eg, ELISA and LFIA) or more than one particular index test (eg, one study evaluated nine different LFIAs). For each particular index test performed in a study, we extracted the numbers needed to construct 2×2 contingency tables. Each evaluation of a particular index test was considered its own study arm. For example, a study that assessed nine LFIAs and two ELISAs on the same set of patients would contribute 11 study arms.

Two reviewers independently assessed risks of bias and applicability concerns using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies 2 (QUADAS-2) tool, for the domains of patient selection, performance of the index test, performance of the reference test, and flow and timing (for risk of bias only).11 Conflicts were resolved through consensus. We performed a quality assessment for each test method and population. For example, an article that assessed nine LFIAs and two ELISAs on the same set of patients would have two QUADAS-2 assessments (one for the LFIAs and one for the ELISAs).

The main summary measures were pooled sensitivity and pooled specificity, with 95% confidence intervals estimated using bivariate generalised linear mixed models. We specified random effects at the level of the particular study and of the particular test. The study level random effect accounted for correlation of results that could arise from study level factors, such as using the same set of samples to evaluate more than one test in a study. The test level random effect was added to account for differences arising from characteristics of individual tests. When models with two random effects did not converge, we used only the test level random effect.

We first estimated pooled sensitivity and specificity by test method (ELISA, LFIA, CLIA) and immunoglobulin class detected (IgM or IgG, or both). Separately, we reported results from studies evaluating serological tests that measured IgA or total immunoglobulin levels and without meta-analyses owing to small numbers. To describe heterogeneity, we constructed summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves with 95% prediction regions, estimated using bivariate meta-analysis with a test level random effect only, and forest plots. As our models were bivariate, we did not use the I2 statistic. Studies that did not report both sensitivity and specificity were excluded from bivariate meta-analyses.

To assess prespecified variables as potential determinants of diagnostic accuracy, we compared pooled sensitivity and specificity across several subgroups according to: peer review status; reporting of data at the level of patients or samples; the type of SARS-CoV-2 antigen used; whether testing was by commercial kit or an in-house assay; whether the population used to estimate specificity consisted of samples collected before the emergence of SARS CoV-2, individuals without suspected covid-19 tested during the epidemic, individuals with suspected covid-19, or individuals with other viral infections; and the timing of sample collection in relation to the onset of symptoms (during the first week, during the second week, or after the second week). In these analyses, to maximize sample size we pooled data regardless of immunoglobulin class. To do so, we used the combined IgG and IgM result when available, otherwise we used the separate IgG and IgM results. For tests that had a 2×2 table for IgM and another 2×2 table for IgG, both contributed arms, sharing the same test level and study level random effects. Because data were not available to study the association between the timing of sampling and specificity, this analysis was done with univariate models and included studies that only reported sensitivity.

We used the statistical software R12 package Lme413 for meta-analyses, and package mada to create summary ROC curves.14

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research question or its outcome measures, conduct of the research, or preparation of the manuscript.

Results

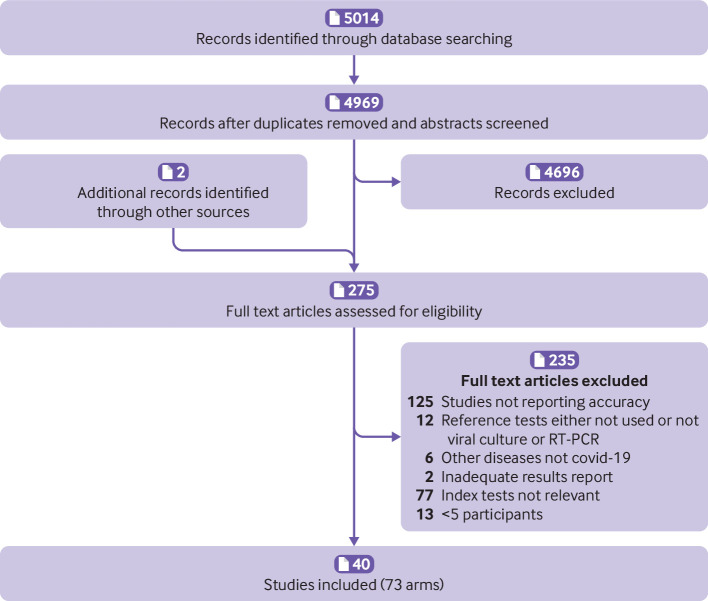

Figure 1 shows the selection of studies. Overall, 5014 records (4969 unique) were identified through database searches and two full text articles from hand searches. In total, 4696 records based on screening of titles or abstracts and 235 after full text review were excluded. Forty studies totalling 73 study arms15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarises the studies by test method; the sum of the number of studies exceeds 40 because some evaluated more than one method. Seventy per cent (28/40) of the studies were from China,16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 38 39 40 41 45 46 47 48 8% (3/40) from Italy,15 36 43 and the remainder from the United States (3/40),42 50 52 Denmark (1/40),51 Spain (1/40),37 Sweden (1/40),53 Japan (1/40),44 the United Kingdom (1/40),49 and Germany (1/40).54 Both sensitivity and specificity were reported in 80% (32/40) of the studies, sensitivity alone in 18% (7/40), and specificity alone in 3% (1/40).33 Among included studies, 50% (20/40) were not peer reviewed. Eighty per cent (32/40) of studies used a case-control design for selecting the study population and 10% (4/40) included outpatient populations. Disease severity was reported in 40% (16/40) and sensitivity stratified by time since symptom onset was reported in 45% (18/40). Several studies used samples rather than individual patients to estimate accuracy. In these studies, one patient could have contributed multiple samples for estimating sensitivity or specificity, or both. Approaches to estimating specificity included using specimens collected before the emergence of covid-19; specimens collected during the epidemic from individuals not suspected of having covid-19, or specimens from individuals with covid-19 symptoms and a negative RT-PCR result for SARS-CoV-2; or specimens from individuals with laboratory confirmed infection with other viruses (respiratory or non-respiratory). Supplementary tables S1 and S2 report the characteristics of each individual study.

Fig 1.

Study selection. RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; covid-19=coronavirus disease 2019

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of included studies, stratified by method of serological testing

| Characteristics | ELISA | LFIA | CLIA | Other* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | No of participants | No of studies | No of participants | No of studies | No of participants | No of studies | No of participants | ||||

| Total | 15 | 2548 | 17† | 1857 | 13 | 3750 | 3 | 140 | |||

| Peer reviewed: | |||||||||||

| Yes | 8 | 1339 | 7 | 859 | 7 | 3090 | 1 | 16 | |||

| No | 7 | 1209 | 11 | 1047 | 6 | 660 | 2 | 123 | |||

| Geographical location: | |||||||||||

| China | 11 | 1572 | 8 | 911 | 12 | 3635 | 1 | 57 | |||

| Denmark | 1 | 112 | 1 | 62 | - | 1 | 16 | ||||

| Italy | - | - | 3 | 301 | 1 | 125 | - | - | |||

| Japan | - | - | 1 | 160 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Spain | - | - | 1 | 100 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Sweden | - | - | 1 | 153 | - | - | - | - | |||

| United Kingdom | 1 | 90 | 1 | 90 | - | - | |||||

| United States | 2 | 774 | 1 | 80 | - | - | 1 | 67 | |||

| Germany | - | - | 1 | 49 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Clinical setting: | |||||||||||

| Inpatient only | 11 | 1307 | 9 | 1508 | 11 | 3119 | 1 | 16 | |||

| Outpatient | - | 49 | 1 | 49 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Inpatient and outpatient | 2 | 170 | 3 | 349 | - | - | |||||

| Not reported | 2 | 1041 | 5 | 778 | 2 | 631 | 2 | 124 | |||

| Study design: | |||||||||||

| Case-control | 15 | 2548 | 12 | 894 | 11 | 3410 | 2 | 83 | |||

| Cohort | 0 | - | 6 | 1012 | 1‡ | 56 | 1 | 57 | |||

| Time from symptom onset to index test§: | |||||||||||

| First week | 6 | 172 | 7 | 190 | 5 | 41 | - | - | |||

| Second week | 7 | 239 | 9 | 195 | 5 | 105 | - | - | |||

| Third week or later | 5 | 159 | 9 | 215 | 5 | 328 | - | - | |||

| Accuracy at level of patient or sample: | |||||||||||

| Patient | 6 | 1495 | 10 | 1407 | 8 | 3080 | 2 | 73 | |||

| Samples†† | 9 | 2115 | 8 | 1252 | 5 | 1599 | 1 | 132 | |||

| Population for estimating specificity‡‡: | |||||||||||

| None | 2 | - | 3 | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | |||

| Stratified | 12 | - | 14 | 8 | - | ||||||

| Samples collected before covid-19 epidemic | 6 | 985 | 5 | 384 | 1 | 330 | 1 | 32 | |||

| Samples collected during covid-19 epidemic in individuals not suspected of having covid-19¶ | 6 | 890 | 3 | 280 | 4 | 2296 | - | - | |||

| Individuals with suspected covid-19 but RT-PCR negative result | - | - | 6 | 378 | 4 | 167 | 1 | 33 | |||

| Individuals with confirmed other viral infection** | 3 | 259 | 1 | 52 | 1 | 167 | - | - | |||

| Mix of above | 1 | 519 | 1 | 32 | 2 | 144 | - | - | |||

ELISA=enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; LFIA=lateral flow immunoassay; CLIA=chemiluminescent immunoassay; RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Includes enzyme immunoassay, fluorescence immunochromatographic assay, liquid phase immunoassay.

Cassaniti et al15 includes two distinct populations, patients who were triaged or admitted to hospital, with different study design (cohort and case-control). This study as two different cohorts, hence sum of number of studies across LFIA rows is 18.

One study was poorly reported, and it was difficult to classify study design.

First week range: 0-7 days (one cohort with 0-10 days is counted in this group); second week: 7-14 days; third week: 15 days or more.

Patients could have contributed more than one sample, and analyses did not account for correlation.

Numbers include samples and patients. Some studies reported more than one type of population to access specificity.

Includes studies where timing was unclear.

Includes some samples originating from before the covid-19 epidemic, and some during the epidemic, as further stratification was not possible.

Table 2 provides information about the serological (index) and reference tests that were used in the included studies. Supplementary table S3 provides details for each study. Most of the studies evaluated commercial serology test kits (see supplementary table S4 for names). Studies varied for measured immunoglobulin class and antigen target. Among 17 studies that evaluated potential point-of-care tests (LFIAs), only two performed testing at the point of care. Direct testing on whole blood specimens—as would be done at the point of care—was performed in 6/17 (35%) studies of LFIAs, and outcomes of such testing were available for 44 patients across all study arms (2% of LFIAs performed). All 39 studies that reported sensitivity used RT-PCR as the reference standard to rule in SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the type and number of specimens varied.

Table 2.

Characteristics of serological (index) and reference tests in included studies (n=40)

| Characteristics* | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Commercial serological kit as index test: | |

| Yes | 23 (58) |

| No | 16 (40) |

| Unclear | 1 (3) |

| Class of immunoglobulin measured by index test: | |

| IgM | 24 (60) |

| IgG | 25 (63) |

| IgM and IgG | 17 (43) |

| IgA | 3 (8) |

| Total Ig | 4 (10) |

| Antigen target of immunoglobulin measured by index test: | |

| Surface protein | 11 (28) |

| Nucleocapsid protein | 8 (20) |

| Surface and nucleocapsid proteins | 14 (35) |

| Not reported | 11 (28) |

| Type of specimen for RT-PCR reference test†: | |

| Nasopharyngeal | 16 (40) |

| Sputum, saliva, or oral, throat, or pharyngeal | 8 (8) |

| Not reported | 15 (38) |

| No of specimens for RT-PCR reference test†: | |

| 2 | 6 (15) |

| 1 or not reported | 33 (85) |

RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

See supplementary table S3 for additional test characteristics of each study. Supplementary table S4 lists the commercial kits.

Denominator is 39 studies reporting sensitivity.

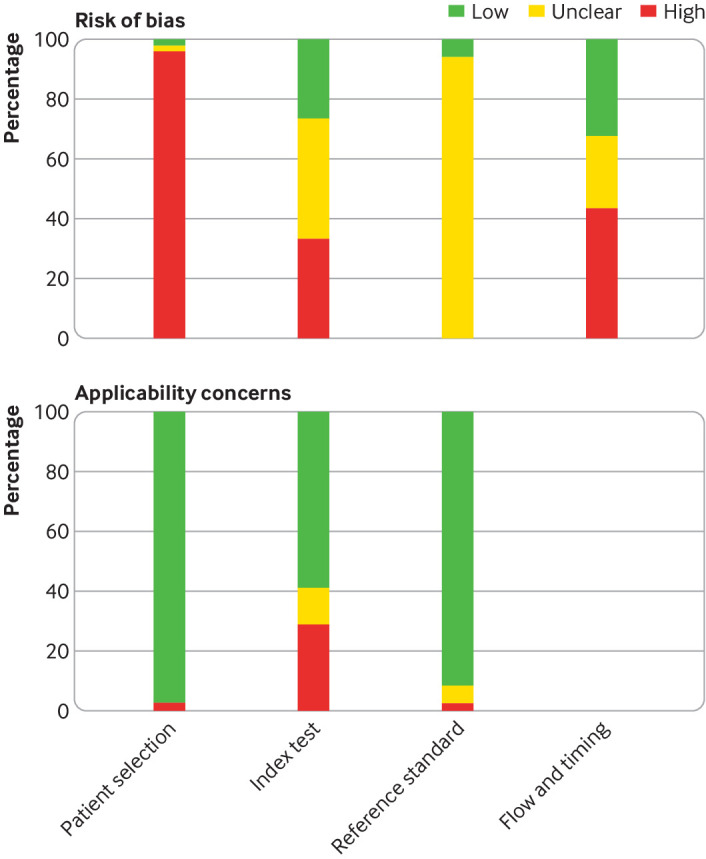

Figure 2 summarises the QUADAS-2 assessment, and supplementary figure S1 displays each of the 49 individual QUADAS-2 evaluations. For the patient selection domain, a high or unclear risk of bias was seen in 98% (48/49) of QUADAS-2 assessments, mostly related to a case-control design and not using consecutive or random sampling. For the index test domain, 73% (36/49) of assessments concluded a high or unclear risk of bias because it was not clear whether the serological test was interpreted blind to the reference standard or whether the cut-off values for classifying results as positive, negative, or indeterminate were prespecified. For LFIAs (18 of the QUADAS-2 assessments), when test results are subjectively interpreted by a human reader (eg, appearance of a line), a description of the number of readers and assessment of reliability were provided in 17% (3/18) of assessments. For the reference standard domain, we judged the risk of bias as unclear in 94% (46/49) of assessments owing to inadequate details about specimens used for RT-PCR or use of specimens other than nasopharyngeal swabs. We also classified the risk as unclear if fewer than two RT-PCRs were used to rule out infection, or if the number was not reported. Risk of bias from flow and timing was high or unclear in 67% (33/49) owing to missing information or results not stratified by the timing of sample collection in relation to symptom onset. Major applicability concerns for the index test were seen in 29% (14/49) of assessments, mostly owing to LFIA being performed in laboratories and not using point-of-care type specimens.

Fig 2.

Summary of quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies 2 (QUADAS-2) assessment

Table 3 enumerates within study and pooled sensitivity stratified by test type and immunoglobulin class. Within each test method (CLIA, ELISA, LFIA), point estimates were similar between the different types of immunoglobulins, and confidence intervals overlapped. Within each class of immunoglobulin, sensitivity was lowest for the LFIA method. Table 4 reports on specificity. Pooled specificities ranged from 96.6% (95% confidence interval 94.3% to 98.2%) for LFIAs measuring IgM and IgG, to 99.7% (99.0% to 100%) for ELISAs measuring IgM. Pooled specificity for CLIA tests that measured IgM and IgG (n=2) could not be estimated because of non-convergence. For all test methods and immunoglobulin classes, visual inspection of summary ROC curves (supplementary figure S2) and of forest plots (supplementary figure S3) showed important heterogeneity.

Table 3.

Individual and pooled sensitivity by serological test method and immunoglobulin class detected*

| Method and studies | IgM | IgG | IgG or IgM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FN | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | TP | FN | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | TP | FN | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | |||

| ELISA (n=13 arms) | |||||||||||

| Liu18 | 174 | 40 | 81.3 (75.6 to 86.0) | 172 | 42 | 80.4 (74.5 to 85.1) | 186 | 28 | 86.9 (81.7 to 90.8) | ||

| Adams49 | 28 | 12 | 70.0 (54.6 to 81.9) | 34 | 6 | 85.0 (70.9 to 92.9) | 34 | 6 | 85.0 (70.9 to 92.9) | ||

| Whitman52: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit | 74 | 56 | 56.9 (48.3 to 65.1) | 96 | 34 | 73.8 (65.7 to 80.6) | 98 | 32 | 75.4 (67.3 to 82.0) | ||

| In-house | - | - | - | - | - | - | 94 | 36 | 72.3 (64.1 to 79.3) | ||

| Liu28 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 127 | 26 | 83.0 (76.3 to 88.1) | ||

| Freeman42 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 95 | 4 | 96.0 (90.0 to 98.4) | ||

| Zhao20 | 143 | 30 | 82.7 (76.3 to 87.6) | 112 | 61 | 64.7 (57.4 to 71.5) | |||||

| Lou30 | 74 | 6 | 92.5 (84.6 to 96.5) | 71 | 9 | 88.8 (80.0 to 94.0) | - | - | - | ||

| Zhong38 | 46 | 1 | 97.9 (88.9 to 99.6) | 46 | 1 | 97.9 (88.9 to 99.6) | - | - | - | ||

| Xiang41 | 51 | 15 | 77.3 (65.8 to 85.7) | 55 | 11 | 83.3 (72.6 to 90.4) | - | - | - | ||

| Perera48 | 37 | 10 | 78.7 (65.8 to 88.0) | 34 | 13 | 72.3 (58.2 to 83.1) | - | - | - | ||

| Guo17 | 62 | 20 | 75.6 (65.3 to 83.6) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Lassauniere51 | - | - | - | 20 | 10 | 66.7 (48.8 to 80.6) | - | - | - | ||

| Pooled | 689 | 190 | 81.1 (71.8 to 88.5) | 640 | 187 | 80.6 (71.9 to 87.9) | 634 | 132 | 84.3 (75.6 to 90.9) | ||

| LFIA (n=36 arms) | |||||||||||

| Li23 | 328 | 69 | 82.6 (78.6 to 86.0) | 280 | 117 | 70.5 (65.9 to 74.8) | 352 | 45 | 88.7 (85.2 to 91.4) | ||

| Garcia37 | 12 | 43 | 21.8 (12.9 to 34.4) | 23 | 32 | 41.8 (29.7 to 55.0) | 26 | 29 | 47.3 (34.7 to 60.2) | ||

| Imai44 | 60 | 79 | 43.2 (35.2 to 51.5) | 20 | 119 | 14.4 (9.5 to 21.2) | 60 | 79 | 43.2 (35.2 to 51.5) | ||

| Whitman52: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit 1 | 79 | 49 | 61.7 (53.1 to 69.7) | 71 | 57 | 55.5 (46.8 to 63.8) | 83 | 45 | 64.8 (56.1 to 72.6) | ||

| Commercial kit 2 | 91 | 37 | 71.1 (62.7 to 78.2) | 80 | 48 | 62.5 (53.0 to 70.4) | 95 | 33 | 74.2 (66.0 to 81.0) | ||

| Commercial kit 3 | 85 | 41 | 67.5 (58.9 to 75.0) | 84 | 42 | 66.7 (58.1 to 74.3) | 85 | 41 | 67.5 (58.9 to 75.0) | ||

| Commercial kit 4 | 94 | 36 | 72.3 (64.1 to 79.3) | 62 | 54 | 53.4 (44.4 to 62.3) | 95 | 35 | 73.1 (64.9 to 80.0) | ||

| Commercial kit 5 | 33 | 82 | 28.7 (21.2 to 37.5) | 72 | 44 | 62.1 (53.0 to 70.4) | 66 | 50 | 56.9 (47.8 to 65.5) | ||

| Commercial kit 6 | 89 | 40 | 69.0 (60.6 to 76.3) | 69 | 60 | 53.5 (44.9 to 61.9) | 91 | 38 | 70.5 (62.2 to 77.7) | ||

| Commercial kit 7 | 62 | 67 | 48.1 (39.6 to 56.6) | 73 | 56 | 56.6 (48.0 to 64.8) | 74 | 55 | 56.9 (47.8 to 65.5) | ||

| Commercial kit 8 | 79 | 51 | 60.8 (52.2 to 68.7) | 73 | 57 | 56.5 (47.6 to 64.4) | 80 | 50 | 61.5 (53.0 to 69.0) | ||

| Commercial kit 9 | 79 | 42 | 65.3 (56.5 to 73.2) | 77 | 44 | 63.6 (54.8 to 71.7) | 79 | 42 | 65.3 (56.5 to 73.2) | ||

| Commercial kit 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 87 | 39 | 69.0 (60.5 to 76.5) | ||

| Liu29 | 34 | 56 | 37.8 (28.5 to 48.1) | 75 | 15 | 83.3 (74.3 to 89.6) | 77 | 13 | 85.6 (76.8 to 91.4) | ||

| Cassaniti15: | |||||||||||

| Hospital admission group | 25 | 5 | 83.3 (66.4 to 92.7) | 24 | 6 | 80.0 (62.7 to90.5) | 25 | 5 | 83.3 (66.4 to 92.7) | ||

| Triage group | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | 31 | 18.4 (9.2 to 33.4) | ||

| Lou30 | 71 | 9 | 88.8 (80.0 to 94.0) | 69 | 11 | 86.2 (77.0 to 92.1) | |||||

| Hoffman53 | 20 | 9 | 69.0 (50.8 to 82.7) | 27 | 2 | 93.1 (78.0 to 98.1) | |||||

| Chen35 | - | 7 | 0 | 100 (64.6 to 100) | |||||||

| Zhang32 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 106 | 16 | 86.9 (79.8 to 91.4) | ||

| Paradiso43 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21 | 49 | 30.7 (20.5 to 41.5) | ||

| Adams49: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 18 | 15 | 54.5 (38.0 to 70.2) | ||

| Commercial kit 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 23 | 15 | 60.5 (44.7 to 74.4) | ||

| Commercial kit 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21 | 12 | 63.6 (46.6 to 77.8) | ||

| Commercial kit 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25 | 12 | 67.6 (51.5 to 80.4) | ||

| Commercial kit 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 19 | 12 | 61.3 (43.8 to 76.3) | ||

| Commercial kit 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | 11 | 64.5 (46.9 to 78.9) | ||

| Commercial kit 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 23 | 10 | 69.7 (52.7 to 82.6) | ||

| Commercial kit 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 18 | 14 | 56.2 (39.3 to 71.8) | ||

| Commercial kit 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22 | 18 | 55.0 (39.8 to 69.3) | ||

| Lassauniere51: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 27 | 3 | 90.0 (74.4 to 96.5) | ||

| Commercial kit 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 27 | 3 | 90.0 (74.4 to 96.5) | ||

| Commercial kit 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 28 | 2 | 93.3 (78.7 to 98.2) | ||

| Commercial kit 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25 | 5 | 83.3 (66.4 to 92.7) | ||

| Commercial kit 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 1 | 80.0 (37.6 to 96.4) | ||

| Commercial kit 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0 | 100 (20.7 to 100) | ||

| Dohla54 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 14 | 36.4 (19.7 to 57.0) | ||

| Pooled | 1241 | 715 | 61.8 (50.8 to 71.8) | 1186 | 764 | 64.9 (53.8 to 75.4) | 1818 | 842 | 66.0 (49.3 to 79.3) | ||

| CLIA (n=10 arms) | |||||||||||

| Lin27 | 65 | 14 | 82.3 (72.4 to 89.1) | 65 | 14 | 82.3 (72.4 to 89.1) | 72 | 7 | 91.1 (82.8 to 95.6) | ||

| Ma47 | 209 | 7 | 96.8 (93.5 to 98.4) | 209 | 7 | 96.8 (93.5 to 98.4) | 215 | 1 | 99.5 (97.4 to 100) | ||

| Cai24 | 158 | 118 | 57.2 (51.3 to 62.9) | 197 | 79 | 71.4 (65.8 to 76.4) | - | - | - | ||

| Infantino36 | 44 | 17 | 72.1 (59.8 to 81.8) | 46 | 15 | 75.4 (63.3 to 84.5) | - | - | - | ||

| Zhong38 | 46 | 1 | 97.9 (88.9 to 99.6) | 45 | 2 | 95.7 (85.8 to 98.8) | - | - | - | ||

| Jin39 | 13 | 14 | 48.1 (30.7 to 66.0) | 24 | 3 | 88.9 (71.9 to 96.1) | - | - | - | ||

| Xie40 | 15 | 1 | 93.8 (71.7 to 98.9) | 16 | 0 | 100 (80.6 to 100) | - | - | - | ||

| Yangchun45 | 144 | 61 | 70.2 (63.7 to 76.1) | 197 | 8 | 96.1 (92.5 to 97.9) | - | - | - | ||

| Qian46 | 432 | 71 | 85.9 (82.6 to 88.7) | 486 | 17 | 96.6 (93.5 to 98.4) | - | - | - | ||

| Lou30 | 69 | 11 | 86.2 (77.0 to 92.1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pooled | 1195 | 315 | 84.3 (70.7 to 93.0) | 1285 | 145 | 93.5 (84.9 to 98.1) | 287 | 8 | 97.8 (46.2 to 100) | ||

Ig=immunoglobulin; TP=true positive; FN=false negative; TN=true negative; FP=false positive; ELISA=enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; LFIA=lateral flow immunoassay; CLIA=chemiluminescent immunoassay.

Pooled estimates were calculated using bivariate random effects meta-analysis; as such, they depart from what would be estimated by simple division of numerator by denominator. Supplementary table S4 lists the names of commercial assays.

Table 4.

Individual and pooled specificity by serological test method and immunoglobulin class detected*

| Method and studies | IgM | IgG | IgG or IgM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TN | FP | Specificity (95% CI) | TN | FP | Specificity (95% CI) | TN | FP | Specificity (95% CI) | |||

| ELISA (n=13 arms) | |||||||||||

| Liu18 | 100 | 0 | 100 (96.3 to 100) | 100 | 0 | 100 (96.3 to 100) | 100 | 0 | 100 (96.3 to 100) | ||

| Adams49 | 50 | 0 | 100 (93.0 to 100) | 50 | 0 | 100 (92.9 to 100) | 50 | 0 | 100 (92.8 to 100) | ||

| Whitman52: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit | 155 | 5 | 96.9 (92.9 to 100) | 142 | 18 | 88.8 (82.9 to 92.8) | 140 | 20 | 87.5 (81.5 to 91.8) | ||

| In-house | - | - | - | - | - | - | 152 | 8 | 95.0 (90.4 to 97.4) | ||

| Liu28 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 116 | 4 | 96.6 (90.1 to 98.4) | ||

| Freeman42 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 515 | 4 | 99.2 (98.0 to 99.7) | ||

| Zhao20 | 210 | 3 | 98.6 (95.9 to 100) | 195 | 2 | 99.0 (96.4 to 99.7) | - | - | - | ||

| Lou30 | 300 | 0 | 100 (98.7 to 100) | 100 | 0 | 100 (96.3 to 100) | - | - | - | ||

| Zhong38 | 299 | 1 | 99.7 (98.1 to 100) | 299 | 1 | 99.7 (98.1 to 100) | - | - | - | ||

| Xiang41 | 60 | 0 | 100 (94.0 to 100) | 57 | 3 | 95.0 (86.3 to 98.3) | - | - | - | ||

| Perera48 | 207 | 0 | 100 (98.7 to 100) | 204 | 3 | 98.6 (95.8 to 100% | - | - | - | ||

| Guo17 | 285 | 0 | 100 (99.0 to 100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Lassauniere51 | - | - | - | 79 | 3 | 96.3 (89.8 to 98.7) | - | - | - | ||

| Pooled | 1666 | 9 | 99.7 (99.0 to 100) | 1226 | 30 | 98.9 (96.7 to 99.8) | 1073 | 36 | 97.6 (93.2 to 99.4) | ||

| LFIA (n=36 arms) | |||||||||||

| Li23 | 117 | 11 | 91.4 (85.3 to 95.1) | 177 | 11 | 94.1 (89.8 to 96.7) | 116 | 12 | 90.6 (84.3 to 94.6) | ||

| Garcia37 | 45 | 0 | 100 (92.1 to 100) | 45 | 0 | 100 (92.1 to 100) | 45 | 0 | 100 (92.1 to 100) | ||

| Imai44 | 47 | 1 | 97.9 (89.1 to 100) | 48 | 0 | 100 (92.6 to 100) | 47 | 1 | 97.9 (89.1 to100) | ||

| Whitman52: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit 1 | 138 | 21 | 86.8 (80.7 to 91.2) | 151 | 8 | 95.0 (90.4 to 97.4) | 134 | 25 | 84.3 (77.8 to 89.1) | ||

| Commercial kit 2 | 141 | 8 | 94.6 (89.8 to 97.3) | 141 | 8 | 95.0 (90.4 to 96.7) | 136 | 13 | 91.3 (85.6 to 94.8) | ||

| Commercial kit 3 | 144 | 15 | 90.6 (85.0 to 94.2) | 148 | 11 | 93.1 (88.0 to 96.1) | 142 | 17 | 89.3 (83.5 to 93.2) | ||

| Commercial kit 4 | 129 | 31 | 80.6 (73.8 to 86.0) | 152 | 6 | 96.2 (92.0 to 98.2) | 129 | 31 | 80.6 (73.8 to86.0) | ||

| Commercial kit 5 | 130 | 6 | 95.6 (90.7 to 98.0) | 134 | 2 | 98.5 (94.8 to 99.6) | 129 | 7 | 94.9 (89.8 to 97.5) | ||

| Commercial kit 6 | 157 | 3 | 98.1 (94.6 to 99.4) | 158 | 2 | 98.8 (95.6 to 100) | 155 | 5 | 96.9 (92.9 to 98.7) | ||

| Commercial kit 7 | 160 | 0 | 100 (97.7 to 100) | 160 | 0 | 100 (97.7 to 100) | 160 | 0 | 100 (97.7 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 8 | 154 | 5 | 96.9 (92.9 to 98.6) | 155 | 4 | 97.5 (93.7 to 99.0) | 154 | 5 | 96.9 (92.9 to 98.7) | ||

| Commercial kit 9 | 139 | 9 | 93.9 (88.8 to 96.8) | 143 | 5 | 96.7 (95.6 to 99.9) | 139 | 9 | 93.9 (88.8 to 96.8) | ||

| Commercial kit 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 146 | 1 | 99.3 (96.2 to 100) | ||

| Liu29 | 83 | 6 | 93.3 (86.1 to 96.9) | 82 | 7 | 92.1 (84.6 to 96.1) | 81 | 8 | 91.0 (83.3 to 95.4) | ||

| Cassaniti15 | |||||||||||

| Hospital admission group | 30 | 0 | 100 (88.6 to 100) | 30 | 0 | 100 (88.6 to100) | 30 | 0 | 100 (88.6 to 100) | ||

| Triage group | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | 1 | 91.7 (64.6 to 98.5) | ||

| Lou30 | 205 | 4 | 98.1 (95.2 to 99.3) | 208 | 1 | 99.5 (97.3 to 100) | - | - | - | ||

| Hoffman53 | 124 | 0 | 100 (97.0 to 100) | 123 | 1 | 99.2 (95.6 to 100) | |||||

| Chen35 | - | - | 11 | 1 | 91.7 (64.6 to 98.5) | ||||||

| Zhang32 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 41 | 0 | 100 (91.4 to 100) | ||

| Paradiso43 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 107 | 13 | 89.2 (82.3 to 93.6) | ||

| Adams49: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit 1 | 60 | 0 | 100 (94.0 to 100) | ||||||||

| Commercial kit 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 90 | 1 | 98.9 (94.0 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 58 | 2 | 96.7 (89.6 to 99.1) | ||

| Commercial kit 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 59 | 2 | 96.7 (89.6 to99.1) | ||

| Commercial kit 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 58 | 2 | 96.7 (89.6 to 99.1) | ||

| Commercial kit 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 59 | 1 | 98.3 (91.1 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 57 | 3 | 95.0 (86.3 to 98.0) | ||

| Commercial kit 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 60 | 0 | 100 (94.0 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 138 | 4 | 97.2 (93.0 to 98.9) | ||

| Lassauniere51: | |||||||||||

| Commercial kit 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32 | 0 | 100 (89.3 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32 | 0 | 100 (89.3 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32 | 0 | 100 (89.3 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 17 | 0 | 100 (81.6 to 100) | ||

| Commercial kit 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | 3 | 80 (54.8 to 93.0) | ||

| Commercial kit 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | 2 | 86.7 (62.1 to 96.3) | ||

| Dohla54 | - | - | - | - | - | 24 | 3 | 88.9 (71.9 to 96.1) | |||

| Pooled | 1943 | 120 | 96.6 (93.8 to 98.4) | 2055 | 66 | 97.6 (96.2 to 98.8) | 2703 | 171 | 96.6 (94.3 to 98.2) | ||

| CLIA (n=10 arms) | |||||||||||

| Lin27 | 65 | 15 | 81.2 (71.3 to 88.3) | 78 | 2 | 97.5 (91.3 to 99.3) | 64 | 16 | 80.0 (70.0 to 87.3) | ||

| Ma47 | 446 | 37 | 92.3 (89.6 to 94.4) | 482 | 1 | 99.8 (98.8 to 100) | 483 | 0 | 100 (99.2 to 100) | ||

| Cai24 | 167 | 0 | 100 (97.8 to100) | 167 | 0 | 100 (97.8 to 100) | - | - | - | ||

| Infantino36 | 60 | 4 | 93.8 (85.0 to 97.5) | 64 | 0 | 100 (94.3 to 100) | - | - | - | ||

| Zhong38 | 286 | 14 | 95.3 (92.3 to 97.2) | 290 | 10 | 96.7 (94.0 to 98.2) | - | - | - | ||

| Jin39 | 33 | 0 | 100 (89.4 to 100) | 30 | 3 | 90.9 (76.4 to 96.9) | - | - | - | ||

| Xie40 | 6 | 34 | 15.0 (7.1 to 29.1) | 0 | 40 | 0.0 (0.0 to 8.8) | - | - | - | ||

| Yangchun45 | 76 | 3 | 96.2 (89.4 to 98.7) | 73 | 6 | 92.4 (84.4 to 96) | - | - | - | ||

| Qian46 | 1529 | 29 | 98.1 (97.3 to 98.7) | 1528 | 30 | 98.1 (97.3 to 98.6) | - | - | - | ||

| Lou30 | 298 | 2 | 99.3 (97.6 to100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pooled | 2966 | 138 | 96.6 (84.7 to 99.5) | 2712 | 92 | 97.8 (62.9 to 99.9) | 547 | 16 | Not estimable | ||

Ig=immunoglobulin; TP=true positive; FN-false negative; TN=true negative; FP=false positive; ELISA=enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; LFIA=lateral flow immunoassay; CLIA=chemiluminescent immunoassay.

Pooled estimates were calculated using bivariate random effects meta-analysis; as such, they depart from what would be estimated by simple division of numerator by denominator. Supplementary table S4 lists the names of commercial assays.

Supplementary table S5 provides sensitivity and specificity reported in three studies that used serological test methods other than ELISAs, LFIAs, or CLIAs. Sensitivity or specificity, or both were low for all, with the exception of an IgM enzyme immunoassay in one arm of 16 patients. Supplementary table S6 reports sensitivity and specificity of serological tests that measured IgA (one ELISA, one CLIA)47 51 and those measuring total immunoglobulin levels (three ELISAs, one CLIA, one LFIA).20 30 51 All four studies were classified as high risk of bias from patient selection, and unclear risk of bias from performance of the reference standard, and three had high or unclear risk of bias in the domains of index test performance and flow and timing (supplementary figure S1). Sensitivity ranged from 93.1% to 98.6%, and specificity from 93.3% to 100%.

Table 5 reports stratified meta-analyses for evaluating potential sources of heterogeneity in sensitivity and specificity. Peer review was not associated with accuracy. For ELISAs and LFIAs, accuracy estimates at the sample level (ie, in studies when it was possible for patients to contribute more than one sample to the analysis) were similar to estimates using only one sample for each patient. For CLIAs, specificity was higher from studies reported at the sample level. Point estimates for pooled sensitivity and specificity were higher when both surface and nucleocapsid proteins were used, although confidence intervals overlapped. Point estimates of pooled sensitivity were lower for commercial kits versus in-house assays, for all three methods, with the strongest difference seen for LFIAs, where the sensitivity of commercial kits was 65.0% (49.0% to 78.2%) and that of non-commercial tests was 88.2% (83.6% to 91.3%). For all three test methods, pooled specificity was high when measured in populations where covid-19 was not suspected, regardless of whether the sampling had been done before or during the epidemic. For both LFIAs and CLIAs, pooled specificity was lower among individuals with suspected covid-19 compared with other groups; similar data were not available for ELISAs. For LFIAs, specificity was lower when estimated in individuals with other viral infections, but this was not the case for ELISAs or CLIAs.

Table 5.

Accuracy of covid-19 serology tests stratified by potential sources of heterogeneity*†

| Potential source of heterogeneity | No of arms | TP | FN | Pooled sensitivity (95% CI) | TN | FP | Pooled specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer reviewed: | |||||||

| ELISA: Yes | 10 | 772 | 190 | 83.7 (74.1 to 92.5) | 1916 | 13 | 99.3 (98.7 to 99.7) |

| ELISA: No | 8 | 613 | 129 | 85.3 (75.7 to 91.9) | 1452 | 39 | 98.4 (94.6 to 99.7) |

| LFIA: Yes | 7 | 446 | 106 | 72.4 (37.9 to 93.6) | 439 | 18 | 96.4 (88.3 to 99.3) |

| LFIA: No | 32 | 1566 | 767 | 70.3 (52.1 to 83.7) | 2935 | 160 | 97.3 (94.9 to 98.6) |

| CLIA: Yes | 8 | 249 | 53 | 89.7 (61.3 to 98.7) | 769 | 105 | 86.5 (80.3 to 99.4) |

| CLIA: No | 9 | 1970 | 373 | 90.5 (73.2 to 97.4) | 4385 | 86 | 99.1 (91.8 to 100) |

| Data level: | |||||||

| ELISA: Patient | 8 | 589 | 133 | 88.2 (67.1 to 96.9) | 1723 | 18 | 98.8 (97.0. 99.5) |

| ELISA: Sample | 11 | 796 | 186 | 82.2 (76.4 to 87.1) | 1655 | 34 | 99.8 (97.8 to 100) |

| LFIA: Patient | 15 | 675 | 211 | 70.7 (46.9 to 86.1) | 799 | 43 | 97.2 (92.8 to 99.4) |

| LFIA: Sample | 24 | 1337 | 662 | 75.1 (56.3 to 95.0) | 2575 | 135 | 97.6 (97.6 to 99.4) |

| CLIA: Patient | 11 | 1490 | 185 | 90.7 (80.3 to 96.8) | 3915 | 185 | 88.4 (48.8. 98.4) |

| CLIA: Sample | 6 | 729 | 241 | 89.3 (45.8 to 96.1) | 1239 | 6 | 99.8 (98.4 to 100) |

| Antigen target | |||||||

| ELISA: | |||||||

| Surface protein | 8 | 573 | 166 | 80.8 (68.1 to 89.9) | 1600 | 35 | 98.3 (94.9 99.6) |

| Nucleocapsid protein | 5 | 389 | 108 | 78.3 (72.5 to 83.2) | 670 | 15 | 98.2 (92.1 to 99.8) |

| Surface and nucleocapsid proteins | 5 | 423 | 45 | 92.5 (80.4 to 98.1) | 1098 | 2 | 99.9 (99.8 to 100) |

| LFIA: | |||||||

| Surface protein | 6 | 594 | 191 | 67.4 (35.7 to 89.4) | 439 | 51 | 92.6 (82.6 to 98.7) |

| Nucleocapsid protein | 1 | 26 | 29 | - | 45 | 0 | - |

| Surface and nucleocapsid proteins | 7 | 363 | 119 | 78.9 (64.4 to 91) | 967 | 20 | 98.7 (91.9 to 100) |

| CLIA: | |||||||

| Surface protein | 1 | 355 | 197 | - | 334 | 0 | - |

| Nucleocapsid protein | 1 | 72 | 7 | - | 64 | 16 | - |

| Surface and nucleocapsid proteins | 10 | 1420 | 152 | 91.6 (72.7 to 98.2) | 4601 | 92 | 98.4 (94.8 to 99.7) |

| Commercial kit: | |||||||

| ELISA: Yes | 10 | 937 | 228 | 80.9 (73.9 to 86.5) | 1357 | 35 | 98.7 (94.4 to 99.8) |

| ELISA: No | 18 | 448 | 91 | 87.3 (72.4 to 95.3) | 2011 | 17 | 99.3 (98.1 to 99.8) |

| LFIA: Yes | 36 | 1547 | 812 | 65.0 (49.0 to 78.2) | 3206 | 165 | 97.0 (94.8 to 98.5) |

| LFIA: No | 3 | 465 | 61 | 88.2 (83.6 to 91.3) | 168 | 13 | 94.9 (79.1 to 99.8) |

| CLIA: Yes | 7 | 227 | 61 | 84.2 (61.4 to 96.3) | 491 | 83 | 90.8 (19.8 to 99.7) |

| CLIA: No | 8 | 1651 | 296 | 93.9 (75.6 to 98.9) | 4515 | 99 | 99.2 (87.0 to 100) |

| Population for estimating specificity† | |||||||

| ELISA: | |||||||

| Samples collected before covid-19 epidemic | 7 | 1360 | 30 | 98.7 (93.4 to 99.9) | |||

| Samples collected during covid-19 epidemic in individuals not suspected of having covid-19 | 10 | - | - | 1441 | 9 | 99.5 (97.9 to 100) | |

| Individuals with suspected covid-19 but RT-PCR negative result | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Individuals with confirmed other viral infection | 5 | - | - | 425 | 21 | 96.3 (62.2 to 100) | |

| LFIA: | |||||||

| Samples collected before covid-19 epidemic | 25 | 2071 | 79 | 98.2 (96.1 to 99.7) | |||

| Samples collected during covid-19 epidemic in individuals not suspected of having covid-19 | 7 | - | - | - | 518 | 5 | 99.0 (97.8 to 100) |

| Individuals with suspected covid-19 but RT-PCR negative result | 7 | - | - | - | 424 | 43 | 90.7 (87.5 to 93.2) |

| Individuals with confirmed other viral infection | 12 | 445 | 56 | 90.8 (76.2 to 95.7) | |||

| CLIA | |||||||

| Samples collected before covid-19 epidemic | 1 | - | - | - | 642 | 18 | - |

| Samples collected during covid-19 epidemic in individuals not suspected of having covid-19 | 7 | - | 4167 | 125 | 97.8 (86.7 to100) | ||

| Individuals with suspected covid-19 but RT-PCR negative result | 8 | - | - | 242 | 92 | 77.1 (15.6 to 98.4) | |

| Individuals with confirmed other viral infection | 1 | - | - | - | 334 | 0 | - |

TP=true positive; FN=false negative; TN=true negative; FP=false positive; ELISA=enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; LFIA=lateral flow immunoassay; CLIA=chemiluminescent immunoassay; RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Pooled estimates were calculated using bivariate random effects meta-analysis; as such, they depart from what would be estimated by simple division of numerator by denominator. Supplementary table S4 lists the names of commercial assays.

Pooled estimates were calculated using univariate random effects meta-analysis.

Table 6 shows pooled sensitivity stratified by the timing of sample collection in relation to symptom onset. Regardless of immunoglobulin class or test method, pooled sensitivity was lowest in the first week of symptom onset and highest in the third week or later. Data on specificity stratified by timing were not available.

Table 6.

Sensitivity by serology test method and timing in relation to onset of symptoms*†

| Time post-onset | IgM | IgG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of arms | TP | FN | Pooled sensitivity (95% CI) | No of arms | TP | FN | Pooled sensitivity (95% CI) | ||

| ELISA: | |||||||||

| First week | 4 | 36 | 99 | 26.7 (15.6 to 35.6) | 5 | 39 | 133 | 23.7 (12.7 to 38.1) | |

| Second week | 5 | 169 | 80 | 57.6 (15.9 to 88.2) | 6 | 165 | 91 | 65.3 (46.3 to 79.4) | |

| Third week or later | 5 | 146 | 32 | 78.4 (54.1 to 91.9) | 6 | 165 | 36 | 82.1 (76.4 to 89.0) | |

| LFIA: | |||||||||

| First week | 15 | 105 | 301 | 25.3 (16.3 to 31.1) | 15 | 74 | 329 | 13.4 (4.7 to 29.6) | |

| Second week | 15 | 471 | 265 | 51.8 (30.3 to 69.6) | 15 | 442 | 312 | 50.1 (24.8 to 77.0) | |

| Third week or later | 15 | 304 | 152 | 69.9 (58.4 to 79.9) | 15 | 361 | 95 | 79.7 (71.4 to 86.9) | |

| CLIA: | |||||||||

| First week | 5 | 28 | 19 | 50.3 (10.9 to 81.2) | 5 | 25 | 22 | 53.2 (28.7 to 67.6) | |

| Second week | 4 | 70 | 33 | 74.3 (16.1 to 99.4) | 4 | 82 | 18 | 85.4 (48.1 to 98.1) | |

| Third week or later | 5 | 280 | 44 | 90.6 (51.8 to 99.4) | 5 | 321 | 7 | 98.9 (86.9 to 100) | |

Ig=immunoglobulin; TP=true positive; FN=false negative; ELISA=enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; LFIA=lateral flow immunoassay; CLIA=chemiluminescent immunoassay.

First week range: 0-7 days (one cohort reporting 0-10 days is counted here), second week: 7-14 days, third week: 15 days or more.

Pooled estimates were calculated using univariate random effects meta-analysis, which is why they depart from estimates calculated by simple division of true positives by the sum of true positives and false negatives.

Table 7 provides a summary of our main findings, with examples of hypothetical testing outcomes for 1000 people undergoing serological testing in settings with a prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 ranging from 5%, 10%, and 20%. For example, in a population with a true SARS-CoV-2 prevalence of 10%, for every 1000 people tested with an LFIA: among those who had covid-19, 66 will test positive and 34 will be incorrectly classified as uninfected. Among those without covid-19, 869 will test negative and 31 will be incorrectly classified as having antibodies to SARS-CoV-2.

Table 7.

Summary of main findings

| Test method | Classification by serology test | Results per 1000 patients tested (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% prevalence | 10% prevalence | 20% prevalence | ||

| Population: SARS-CoV-2 infected | ||||

| ELISA (IgG or IgM): | ||||

| 9 studies, 766 samples. Pooled sensitivity 84.3% (95% CI 75.6% to 90.9%) | Correctly classified as infected | 42 (38 to 45) | 84 (76 to 91) | 169 (151 to 182) |

| Incorrectly classified as uninfected | 8 (5 to 12) | 16 (9 to 24) | 31 (18 to 49) | |

| LFIA (IgG or IgM): | ||||

| 11 studies, 2660 samples. Pooled sensitivity 66.0% (95% CI 49.3% to 79.3%) | Correctly classified as infected | 33 (25 to 40) | 66 (49 to 79) | 132 (99 to 159) |

| Incorrectly classified as uninfected | 17 (10 to 25) | 34 (21 to 51) | 68 (41 to 101) | |

| CLIA (IgG or IgM): | ||||

| 2 studies, 375 samples. Pooled sensitivity 97.8% (95% CI 46.2% to 100%) | Correctly classified as infected | 49 (23 to 50) | 98 (46 to 100) | 196 (92 to 200) |

| Incorrectly classified as uninfected | 1 (0 to 27) | 2 (0 to 54) | 4 (0 to 108) | |

| Population: not infected with SARS-CoV-2 | ||||

| ELISA (IgG or IgM): | ||||

| 6 studies, 1109 samples. Pooled specificity 97.6% (95% CI 93.2% to 99.4%) | Correctly classified as uninfected | 931 (884 to 941) | 882 (837 to 891) | 784 (744 to 792) |

| Incorrectly classified as infected | 19 (9 to 66) | 18 (9 to 63) | 16 (8 to 56) | |

| LFIA (IgG or IgM): | ||||

| 11 studies, 2874 samples. Pooled specificity 96.6% (95% CI 94.3% to 98.2%) | Correctly classified as uninfected | 918 (896 to 933) | 869 (849 to 884) | 773 (754 to 786) |

| Incorrectly classified as infected | 32 (17 to 54) | 31 (16 to 51) | 27 (14 to 46) | |

| CLIA (IgG): | ||||

| 9 studies, 2804 samples. Pooled specificity 97.8% (95% CI 62.9% to 99.9%) | Correctly classified as uninfected | 929 (598 to 949) | 880 (566 to 899) | 782 (503 to 799) |

| Incorrectly classified as infected | 21 (1 to 352) | 20 (1 to 334) | 18 (1 to 297) | |

Quality of evidence and practical implications: Pooled sensitivity and specificity should be interpreted with caution. Accuracy might have been over-estimated in most studies owing to bias arising from patient selection or how index and reference tests were performed, or both. Estimates of sensitivity and specificity were inconsistent between studies (heterogeneity was important). Estimates might have limited applicability to outpatient settings and for testing at the point of care. Point-of-care LFIAs consistently had the lowest sensitivity and specificity. The poorest performance was seen with commercial LFIA kits; these tests should not be used for clinical purposes. Clinical studies designed to overcome the weaknesses are urgently needed.

RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; ELISA=enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; LFIA=lateral flow immunoassay; CLIA=chemiluminescent immunoassay; Ig=immunoglobulin; SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; covid-19=coronavirus disease 2019.

Index test: serology tests to detect immunoglobulins to SARS-CoV-2. Target condition: covid-19, reference standard: RT-PCR, Studies: predominantly case-control design diagnostic test accuracy.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, existing evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for covid-19 was found to be characterised by high risks of bias, heterogeneity, and limited generalisability to point-of-care testing and to outpatient populations. We found sensitivities were consistently lower with the LFIA method compared with ELISA and CLIA methods. For each test method, the type of immunoglobulin being measured—IgM, IgG, or both—was not associated with diagnostic accuracy. Pooled sensitivities were lower with commercial kits and in the first and second week after symptom onset compared with the third week or later. Pooled specificities of each test method were high. However, stratified results suggested specificity was lower in individuals with suspected covid-19, and that other viral infections could lead to false positive results for the LFIA method. These observations indicate important weaknesses in the evidence on covid-19 serological tests, particularly those being marketed as point-of-care tests.

Meaning of the study

The utility of a low cost, rapid, and accurate point-of-care test55 has spurred the development and marketing of several covid-19 LFIA serological tests.56 We found only two studies where LFIA had been performed at the point of care. The low sensitivity of LFIA is of particular concern given that most studies used sample preparation steps that are likely to increase sensitivity compared with the use of whole blood as would be done at the point of care. These observations argue against the use of LFIA serological tests for covid-19 beyond research and evaluation purposes and support interim recommendations issued by the World Health Organization.57

Cautious interpretation of specificity estimates is warranted for several reasons. Importantly, few data were available from people who were tested because of suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection; hence our overall pooled estimates might not be generalisable to people who need testing because of covid-19 symptoms. For CLIAs, the lower specificity among people with suspected covid-19 could be a spurious finding from a false negative RT-PCR result, given that the specificity for CLIAs was high among people with confirmed other viral infections. By contrast, for LFIAs, other viral infections could have contributed to the lower specificity in suspected covid-19.

Our time stratified analyses suggest that current serological tests for covid-19 have limited utility in the diagnosis of acute covid-19. For example, of those tested for covid-19 within one week of symptom onset, on average 44% to 87% will be falsely identified as not having infection. And while sensitivity estimates were higher in the third week or later, even at this time point we found important false negative rates. For example, in people with covid-19 who are tested three weeks after symptom onset, ELISA IgG will misclassify 18% as not having been infected and LFIA IgG will misclassify 30%.

Overall, the poor performance of existing serological tests for covid-19 raises questions about the utility of using such methods for medical decision making, particularly given time and effort required to do these tests and the challenging workloads many clinics are facing. Our findings should also give pause to governments that are contemplating the use of serological tests—in particular, point-of-care tests—to issue immunity “certificates” or “passports.” For example, if an LFIA is applied to a population with a true SARS-CoV-2 prevalence of 10%, for every 1000 people tested, 31 who never had covid-19 will be incorrectly told they are immune, and 34 people who had covid-19 will be incorrectly told that they were never infected.

Strengths and limitations of this review

Our review has several strengths. We used sensitive search strategies and included pre-peer reviewed literature, and although our use of studies published as preprints might be criticised, we found that the peer reviewed literature also had biases. Moreover, preprints have taken an unprecedented larger role58 in discussions and policy making around covid-19—hence the importance of subjecting pre-peer reviewed literature to critical appraisal. Another strength of our review was that two independent reviewers systematically assessed potential sources of bias. Finally, a second investigator verified all data extraction.

Our study also has some limitations. Most importantly, we compared pooled estimates between different study populations. As such, the possibility of confounding exists (eg, from differences in timing of sampling between studies), explaining differences in sensitivity or specificity.59 This approach was taken because few studies performed head-to-head comparisons. We did not perform metaregression as many studies would have been excluded owing to limited reporting of covariates. Another limitation is that as we did not search Embase we might have missed some published studies.

Conclusion and future research

Future studies to evaluate serological tests for covid-19 should be designed to overcome the major limitations of the existing evidence base. This can be readily accomplished by adhering to the fundamentals of the design for diagnostic accuracy studies: a well defined use-case (ie, specific purpose for which the test is being used); consecutive sampling of the target population within the target use-case; performance of the index test in a standardised and blinded manner using the same methods that will be applied in the specialty; and ensuring the reference test is accurate, performed on all participants, and interpreted blind to the results of the index test. To reduce the likelihood of misclassification, the reference standard should consist of RT-PCR performed on at least two consecutive specimens, and, when feasible, include viral cultures. To reduce variability in estimates and enhance generalisability, sensitivity and specificity should be stratified by setting (outpatient versus in-patient), severity of illness, and the number of days elapsed since symptom onset.

In summary, we have found major weaknesses in the evidence base for serological tests for covid-19. The evidence does not support the continued use of existing point-of-care serological tests for covid-19. While the scientific community should be lauded for the pace at which novel serological tests have been developed, this review underscores the need for high quality clinical studies to evaluate these tools. With international collaboration, such studies could be rapidly conducted and provide less biased, more precise, and more generalisable information on which to base clinical and public health policy to alleviate the unprecedented global health emergency that is covid-19.

What is already known on this topic

Serological tests to detect antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) could improve diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) and be useful tools for epidemiological surveillance

The number of serological tests has rapidly increased, and many are being marketed for point-of-care use

The evidence base supporting the diagnostic accuracy of these tests, however, has not been formally evaluated

What this study adds

The available evidence on the accuracy of serological tests for covid-19 is characterised by risks of bias and heterogeneity, and as such, estimates of sensitivity and specificity are unreliable and have limited generalisability

Evidence is particularly weak for point-of-care serological tests

Caution is warranted if using serological tests for covid-19 for clinical decision making or epidemiological surveillance

Current evidence does not support the continued use of existing point-of-care tests

Acknowledgments

We thank Geneviève Gore, McGill University Academic Librarian, for assistance in developing the search strategy for Ovid-Medline and the preprint literature, and Coralie Gesic for designing the forest plots. The study protocol is available at www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=179452.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: additional tables and figures

Contributors: MLB and FAK (equally) and AB, DM, and JC conceived the study and study design. MLB drafted the initial search strategy and executed the search. MLB, GT, and FAK screened the studies. MLB, GT, SL, EM, AT, ZL, and SA extracted data extraction and performed the quality assessment. MLB, AB, FAK, and ZL analysed the data. MLB and FAK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FAK is the guarantor. All authors interpreted the data and wrote and critically reviewed the manuscript and all revisions. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was funded (publication costs) by a grant (ECRF-R1-30) from the McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity (MI4). MB is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (award #FRD143350). JRC is supported by Fonds de Recherche Sante Quebec (FRSQ award #258907 and #287869). SL holds a research training award from the FRSQ. AB holds a research salary award from the FRSQ. AT is supported by Conselho Nacional de Ensino, Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Tecnológico (award #303267/2018-6). FAK receives salary support from the McGill University Department of Medicine. MI4 and these agencies had no input into the study design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation, report writing, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: SL reports personal fees from Carebook Technologies, outside the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: Data can be requested from the corresponding author.

The study guarantor (FAK) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The results of the meta-analysis will be disseminated to patients, providers, policy makers through social media, and academic and institutional networks.

References

- 1. Winichakoon P, Chaiwarith R, Liwsrisakun C, et al. Negative nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs do not rule out covid-19. J Clin Microbiol 2020;58:e00297-20. 10.1128/JCM.00297-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Z, Li Y, Wu B, Hou Y, Bao J, Deng X. A patient with covid-19 presenting a false-negative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction result. Korean J Radiol 2020;21:623-4. 10.3348/kjr.2020.0195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. Interpreting Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.8259 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.American Society for Microbiology. ASM expresses concern about coronavirus test reagent shortages. https://asm.org/Articles/Policy/2020/March/ASM-Expresses-Concern-about-Test-Reagent-Shortages. 2020

- 5.Maxmen A. The researchers taking a gamble with antibody tests for coronavirus. Nature 2020. 10.1038/d41586-020-01163-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saah AJ, Hoover DR. “Sensitivity” and “specificity” reconsidered: the meaning of these terms in analytical and diagnostic settings. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:91-4. 10.7326/0003-4819-126-1-199701010-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meyer B, Drosten C, Müller MA. Serological assays for emerging coronaviruses: challenges and pitfalls. Virus Res 2014;194:175-83. 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Woo PC, Lau SK, Wong BH, et al. Differential sensitivities of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus spike polypeptide enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein ELISA for serodiagnosis of SARS coronavirus pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:3054-8. 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3054-3058.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woo PCY, Lau SKP, Wong BHL, et al. Detection of specific antibodies to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus nucleocapsid protein for serodiagnosis of SARS coronavirus pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:2306-9. 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2306-2309.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2 Group . QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:529-36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.R: A language and environment for statistical computing [program]: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019. https://www.r-project.org/

- 13. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 2015;67:48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v067i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy with mada. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mada/vignettes/mada.pdf [program], 2019.

- 15. Cassaniti I, Novazzi F, Giardina F, et al. Members of the San Matteo Pavia COVID-19 Task Force . Performance of VivaDiag COVID-19 IgM/IgG Rapid Test is inadequate for diagnosis of COVID-19 in acute patients referring to emergency room department. J Med Virol 2020;30:30. 10.1002/jmv.25800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao HX, Li YN, Xu ZG, et al. Detection of serum immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G antibodies in 2019 novel coronavirus infected patients from different stages. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1479-80. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guo L, Ren L, Yang S, et al. Profiling early humoral response to diagnose novel coronavirus disease (covid-19). Clin Infect Dis 2020;21:21. 10.1093/cid/ciaa310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu W, Liu L, Kou G, et al. Evaluation of nucleocapsid and spike protein-based ELISAs for detecting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol 2020;30:30. 10.1128/JCM.00461-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9:386-9. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 2020;28:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xiao AT, Gao C, Zhang S. Profile of specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2: The first report. J Infect 2020;81:147-78. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. To KK, Tsang OT, Leung WS, et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:565-74. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li Z, Yi Y, Luo X, et al. Development and clinical application of a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. J Med Virol 2020;27:27. 10.1002/jmv.25727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cai X, Chen J, Hu J, et al. A peptide-based magnetic chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay for serological diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19). MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.02.22.20026617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gao Y, Yuan Y, Li TT, et al. Evaluation the auxiliary diagnosis value of antibodies assays for detection of novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) causing an outbreak of pneumonia (COVID-19). MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.26.20042044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jia X, Zhang P, Tian Y, et al. Clinical significance of IgM and IgG test for diagnosis of highly suspected COVID-19 infection. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.02.28.20029025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin D, Liu L, Zhang M, et al. Evaluations of serological test in the diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infections during the COVID-19 outbreak. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.27.20045153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu L, Liu W, Wang S, et al. A preliminary study on serological assay for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 238 admitted hospital patients. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.06.20031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu Y, Liu Y, Diao B, et al. Diagnostic Indexes of a Rapid IgG/IgM Combined Antibody Test for SARS-CoV-2. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.26.20044883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lou B, Li T, Zheng S, et al. Serology characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infection since the exposure and post symptoms onset. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.23.20041707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pan Y, Li X, Yang G, et al. Serological immunochromatographic approach in diagnosis with SARS-CoV-2 infected COVID-19 patients. J Infect 2020;81:e28-32. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang P, Gao Q, Wang T, et al. Evaluation of recombinant nucleocapsid and spike proteins for serological diagnosis of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.17.20036954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhao R, Li M, Song H, et al. Serological diagnostic kit of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies using CHO-expressed full-length SARS-CoV-2 S1 proteins. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.26.20042184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Long Qx, Deng Hj, Chen J, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients: the perspective application of serological tests in clinical practice. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.03.18.20038018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen Z, Zhang Z, Zhai X, et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG using lanthanide-doped nanoparticles-based lateral flow immunoassay. Anal Chem 2020;92:7226-31. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Infantino M, Grossi V, Lari B, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of an automated chemiluminescent immunoassay for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies: an Italian experience. J Med Virol 2020;24:24. 10.1002/jmv.25932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garcia FP, Perez Tanoira R, Romanyk Cabrera JP, et al. Rapid diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection by detecting IgG and IgM antibodies with an immunochromatographic device: a prospective single-center study. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.11.20062158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhong L, Chuan J, Gong B, et al. Detection of serum IgM and IgG for COVID-19 diagnosis. Sci China Life Sci 2020;63:777-80. 10.1007/s11427-020-1688-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jin Y, Wang M, Zuo Z, et al. Diagnostic value and dynamic variance of serum antibody in coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:49-52. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xie J, Ding C, Li J, et al. Characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) confirmed using an IgM-IgG antibody test. J Med Virol 2020;24:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xiang F, Wang X, He X, et al. Antibody Detection and Dynamic Characteristics in Patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2020;19:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Freeman B, Lester S, Mills L, et al. Validation of a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein ELISA for use in contact investigations and serosurveillance. bioRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.24.057323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paradiso AV, De Summa S, Loconsole D, et al. Clinical meanings of rapid serological assay in patients tested for SARS-Co2 RT-PCR. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.03.20052183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Imai K, Tabata S, Ikeda M, et al. Clinical evaluation of an immunochromatographic IgM/IgG antibody assay and chest computed tomography for the diagnosis of COVID-19. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.22.20075564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yangchun F. Optimize Clinical Laboratory Diagnosis of COVID-19 from Suspect Cases by Likelihood Ratio of SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibody. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.07.20053660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Qian C, Zhou M, Cheng F, et al. Development and Multicenter Performance Evaluation of The First Fully Automated SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG Immunoassays. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.16.20067231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ma H, Zeng W, He H, et al. COVID-19 diagnosis and study of serum SARS-CoV-2 specific IgA, IgM and IgG by a quantitative and sensitive immunoassay. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.17.20064907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Perera RA, Mok CK, Tsang OT, et al. Serological assays for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), March 2020. Euro Surveill 2020;25:2000421. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.16.2000421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Adams ER, An R, et al. Evaluation of antibody testing for SARS-Cov-2 using ELISA and lateral flow immunoassaysP. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.15.20066407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burbelo PD, Riedo FX, Morishima C, et al. Detection of Nucleocapsid Antibody to SARS-CoV-2 is More Sensitive than Antibody to Spike Protein in COVID-19 Patients. medRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.20.20071423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lassauniere R, Frische A, Harboe ZB, et al. Evaluation of nine commercial SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays. MedRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.09.20056325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Whitman JD, Hiatt J, Mowery CT, et al. Test performance evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 serological assays. medRxiv (Preprint). 10.1101/2020.04.25.20074856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hoffman T, Nissen K, Krambrich J, et al. Evaluation of a COVID-19 IgM and IgG rapid test; an efficient tool for assessment of past exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2020;10:1754538. 10.1080/20008686.2020.1754538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Döhla M, Boesecke C, Schulte B, et al. Rapid point-of-care testing for SARS-CoV-2 in a community screening setting shows low sensitivity. Public Health 2020;182:170-2. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Beeching NJ, Fletcher TE, Beadsworth MBJ. Covid-19: testing times. BMJ 2020;369:m1403. 10.1136/bmj.m1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Petherick A. Developing antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet 2020;395:1101-2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30788-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. World Health Organization . Advice on the use of point-of-care immunodiagnostic tests for COVID-19: scientific brief, 8 April 2020. WHO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Majumder MS, Mandl KD. Early in the epidemic: impact of preprints on global discourse about COVID-19 transmissibility. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e627-30. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30113-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Deeks JJ. Systematic reviews in health care: Systematic reviews of evaluations of diagnostic and screening tests. BMJ 2001;323:157-62. 10.1136/bmj.323.7305.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: additional tables and figures