Abstract

Rationale: Metabolic syndrome (MetS), the clinical clustering of hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and abdominal obesity, has been associated with a prothrombotic and hypofibrinolytic state, although data linking MetS with venous thromboembolism (VTE) remain limited.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to measure the prevalence of MetS in patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) across a large population and to examine its impact on VTE recurrence.

Methods: This was a retrospective, population-based analysis using deidentified information from a large statewide database, the Indiana Network for Patient Care. All patients with an International Classification of Diseases–defined diagnosis of PE from 2004 to 2017 were included. We measured the frequency with which patients with PE carried a comorbid diagnosis of each MetS component. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed with VTE recurrence as the dependent variable to test the independent effect of MetS diagnosis, with a statistical model using a directed acyclic graph to account for potential confounders and mediators. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to compare rates of VTE recurrence over time based on the presence or absence of MetS and its individual components.

Results: A total of 72,936 patients were included in this analysis. The most common MetS component was hypertension with a prevalence of 59%, followed by hyperlipidemia (41%), diabetes mellitus (24%), and obesity (22%). Of these patients, 69% had at least one comorbid component of MetS. The overall incidence of VTE recurrence was 17%, increasing stepwise with each additional MetS component and ranging from 6% in patients with zero components to 37% in those with all four. Logistic regression analysis yielded an adjusted odds ratio of 3.03 (95% CI, 2.90–3.16) for the effect of composite diagnosis requiring at least three of the four components of MetS diagnosis on VTE recurrence.

Conclusions: The presence of comorbid MetS in patients with PE is associated with significantly higher rates of VTE recurrence, supporting the importance of recognizing these risk factors and initiating appropriate therapies to reduce recurrence risk.

Keywords: pulmonary embolism, metabolic syndrome, venous thromboembolism recurrence, obesity, hyperlipidemia

Metabolic syndrome (MetS), the clinical clustering of hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and abdominal obesity, continues to be a public health concern of rising importance as its prevalence becomes increasingly widespread (1–4). Current estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey suggest that more than one-third of all U.S. adults now meet criteria for a diagnosis of MetS, increasing from 25% between 1988 and 1994 to 34% between 2007 and 2012 (5). MetS has been shown to confer numerous adverse health consequences, with prior studies demonstrating a significant increased risk of the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (6–9). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 87 studies found MetS to be associated with a twofold increase in cardiovascular outcomes and a 1.5-fold increase in all-cause mortality (10). Although the underlying mechanism of MetS is not clearly understood, it is hypothesized that increased adipose tissue may result in adipocyte dysregulation, tissue hypertrophy, and eventual hypoxia, with an amplified production of proinflammatory adipocytokines. This may lead to increased insulin resistance and a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state (11–13).

Important to the study of venous thromboembolism (VTE), MetS has been previously shown to be associated with a prothrombotic and hypofibrinolytic state. Our prior work demonstrated prolonged tissue plasminogen activator–catalyzed clot lysis times in plasma samples obtained from patients with MetS compared with control subjects (14). However, overall data linking MetS with VTE remain limited to retrospective analyses of small databases (15–21). Pulmonary embolism (PE) is the third most common cardiovascular disease and carries with it a significant risk of adverse health outcomes (22). Acute PE can be lethal, with an estimated 10% short-term mortality rate for normotensive PE with right ventricular strain, termed intermediate-risk PE (23). Furthermore, among the nonfatal consequences of PE is the risk of recurrence, with one study citing an 11% recurrence rate one year after diagnosis as well as a cumulative incidence of recurrence of 53% after the maximum follow-up period of 10 years (24).

Recurrent VTE increases the risk of mortality, prolongs the duration of anticoagulation therapy, and decreases patient quality of life (25). Given the potential deleterious effects of recurrent VTE, several clinical prediction tools have been developed to assist in the identification of these at-risk patients. Of the components of MetS, only obesity has been consistently recognized in prediction tools as a risk factor for recurrence (26, 27). An improved understanding of the role that MetS plays in VTE and its recurrence could better inform clinicians on the most appropriate management of these patients, including the potential benefit of the initiation of adjuvant therapies aimed at the reduction of MetS components, if they indeed are demonstrated to increase risk of recurrence. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of MetS across a large statewide population of patients with PE and to examine its role in subsequent VTE recurrence.

Methods

Overall Study Design

This was a retrospective population-based analysis using deidentified information from patients with a diagnosis of PE included in a large statewide database, the Indiana Network for Patient Care (INPC). This database includes information from over 100 healthcare entities, including hospitals, health networks, and insurance companies, and represents one of the largest health information exchanges nationwide, estimated to include data on more than 18 million patients and 10 billion clinical observations in total. Data collection was performed in collaboration with the Regenstrief Data Core, which, in addition to the INPC database, also extracted data from the Eskenazi Health and Indiana University Health data warehouses. Inclusion in this study required the diagnosis of PE based on sequel-based retrospective query of these databases for the appropriate International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (with specific ICD indexing as follows: ICD-9 [415.x] or ICD-10 [I26.x]), over the predetermined study period of 2004 to 2017.

Data collected on patients found to have an ICD-defined diagnosis of PE included demographic data (e.g., age, sex, race), as well as the presence or absence of several comorbid conditions of interest. The presence or absence of each of the individual components of MetS was again determined based on ICD coding associated with a diagnosis of the following conditions: hypertension (401–404.x, I10-I13.x), hyperlipidemia (272.x, E78.x, E88.1), diabetes mellitus (250.x0, 250.x2, E11.x), or obesity (278.x, E66.x). The presence of additional comorbidities, including atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), anxiety, depression, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and cancer (esophageal, breast, lung, liver, testicular, pancreatic, prostate, ovarian, and melanoma) was also defined. We recorded the number of return visits to the emergency department from the index date to two years after PE diagnosis, as well as the presence or absence of an ICD diagnosis of recurrent VTE. The complete data dictionary displaying the specific ICD codes used to define each variable can be found in the online supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (version 9.4, https://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html). We measured the individual prevalence of each of the components of MetS in patients with PE. We also calculated the summative frequency with which patients carried a diagnosis of zero, one, two, three, and four of these MetS components. To better measure the impact of MetS while considering the influence of other clinical factors that could affect risk of VTE recurrence post hoc, we developed a statistical model using a directed acyclic graph (DAG), shown in Figure 1 (28–30). Because the components of MetS are interdependent, we included the presence or absence of a composite diagnosis requiring at least three of the four components of MetS (+MetS) rather than including each individual MetS component, to reduce model overfit. In the DAG model, we included age, sex, smoking history, atrial fibrillation, COPD, CHF, CKD, anxiety, depression, stroke, MI, and cancer. Of these variables, we determined CHF, CKD, stroke, MI, and atrial fibrillation to be mediators in the pathway from MetS to VTE recurrence because mediation testing suggested each of these variables to be a partial driver of this relationship (31–36). These mediators were removed from the final regression equation. Age, sex, smoking history, and cancer were identified as likely confounders in the relationship between MetS and VTE recurrence, given their previously established role in VTE recurrence, and were, therefore, included in the logistic regression equation (37–39). We deemed COPD, anxiety, and depression to be neither potential mediators nor confounders in this relationship and excluded them from our final model. Using this final DAG model, we conducted multiple logistic regression analysis with VTE recurrence as the dependent variable and the following independent variables: +MetS, age, sex, smoking history, and cancer. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for VTE recurrence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all included variables. Logistic regression for multiple comparisons was then used to further compare the odds of recurrence between groups stratified by the number of MetS criteria (zero to four) and was adjusted with the Bonferroni correction. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to plot VTE recurrence over time, based on the presence or absence of each individual component of MetS, and results were compared with the log-rank test. Kaplan-Meier analysis was also conducted to compare rates of recurrence in patients classified as having the composite +MetS diagnosis versus those without MetS.

Figure 1.

Directed acyclic graph demonstrating the effect of metabolic syndrome on VTE recurrence. The orange nodes above represent confounders in the logistic regression equation, the light blue nodes below represent mediators, and the blue nodes represent factors that were neither confounders nor mediators and were excluded. VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Results

This study included a total of 72,936 patients with a diagnosis of PE with a median follow-up period of 5.5 years, representing 408,920 total person-years. Pertinent demographic and comorbidity data are included in Table 1. The mean age was 58 years and 55% were female. Hypertension was the most common comorbid component of MetS in patients with PE, with a prevalence of 59%. This was followed by hyperlipidemia (41%), diabetes mellitus (24%), and obesity (22%). COPD was the most prevalent non-MetS comorbidity, present in 33% of patients. Patients had an overall incidence of VTE recurrence of 17% and mortality of 17%. There was an average of 2.1 return visits to the emergency department per patient in the two years following PE diagnosis.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes stratified by number of metabolic syndrome criteria

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients, n | 22,609 | 16,006 | 16,984 | 12,875 | 4,462 | 72,936 |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 54 (20) | 59 (19) | 62 (16) | 60 (15) | 57 (13) | 58 (18) |

| Sex, female, % | 54 | 56 | 54 | 57 | 58 | 55 |

| White, % | 63 | 68 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 69 |

| Black, % | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 |

| Hypertension, % | 0 | 64 | 92 | 98 | 100 | 59 |

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 0 | 15 | 68 | 90 | 100 | 41 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 0 | 12 | 21 | 57 | 100 | 24 |

| Obesity, % | 0 | 9 | 19 | 55 | 100 | 22 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 6 | 19 | 28 | 33 | 34 | 20 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, % | 12 | 32 | 42 | 51 | 55 | 33 |

| Congestive heart failure, % | 7 | 26 | 37 | 47 | 51 | 28 |

| Chronic kidney disease, % | 3 | 15 | 26 | 36 | 36 | 19 |

| Anxiety, % | 2 | 4 | 55 | 9 | 11 | 5 |

| Depression, % | 8 | 21 | 31 | 42 | 48 | 25 |

| Stroke, % | 2 | 8 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 10 |

| Myocardial infarction, % | 2 | 6 | 12 | 16 | 17 | 9 |

| Cancer, % | 13 | 17 | 18 | 17 | 14 | 15 |

| Smoking history, % | 14 | 26 | 35 | 43 | 51 | 29 |

| Venous thromboembolism recurrence, % | 6 | 13 | 20 | 29 | 37 | 17 |

| Mortality, % | 13 | 20 | 19 | 17 | 13 | 17 |

| Mean return emergency department visits, n (SD) | 1.2 (4.9) | 1.9 (7.1) | 2.5 (10.3) | 3.1 (11.9) | 3.5 (11.6) | 2.1 (9.1) |

Definition of abbreviation: SD = standard deviation.

Table 1 also stratifies patients based on the number of ICD-coded MetS criteria (zero to four) they were found to have. Sixty-nine percent of patients with PE carried a comorbid diagnosis of at least one component of MetS. Stratification into groups based on the number of MetS criteria yielded the following results: 31% with zero components, 22% with one component, 23% with two components, 18% with three components, and 6% with all four components. Patients with all four components of MetS were significantly older than patients without any of these diagnoses (57 yr vs. 54 yr; P < 0.0001) and had larger proportions of additional comorbidities. VTE recurrence increased in a stepwise fashion with each additional component of MetS. Patients without any MetS diagnoses had, on average, a 6% incidence of VTE recurrence over time compared with 13% recurrence in patients with one MetS component, 20% with two components, 29% with three components, and 37% with all four components. Presence of MetS components was associated with increased healthcare use, with an average of 1.2 return emergency department visits in the two years following PE diagnosis in patients with zero MetS components, followed by 1.9 visits in those with one component, 2.5 visits with two components, 3.1 visits with three components, and 3.5 visits in those with all four components.

A refined statistical model using a DAG (see Figure 1) identified CHF, CKD, stroke, MI, and atrial fibrillation as potential mediators in the pathway of MetS to VTE recurrence, thereby removing these adjustment factors from the original regression model. The final DAG model exploring the role of composite +MetS diagnosis on the dependent variable of VTE recurrence included the following confounders: age, sex, smoking history, and cancer history. Results from this multivariate logistic regression analysis are displayed in Table 2. This model yielded an adjusted OR of 3.03 (95% CI, 2.90–3.16) for the effect of +MetS on VTE recurrence. The adjusted ORs for the confounder variables included in this regression equation were as follows: age (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.99–1.00), male sex (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.89–0.97), smoking history (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.42–1.55), and cancer (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.08–1.20).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis with associated adjusted odds ratios for venous thromboembolism recurrence using the directed acyclic graph model

| Variable | Venous Thromboembolism Recurrence |

|

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimates (P Value) | Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Age | −0.0060 (<0.0001) | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) |

| Sex, male | −0.0725 (0.0005) | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.97) |

| Smoking history | 0.3928 (<0.0001) | 1.48 (1.42 to 1.55) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 1.1071 (<0.0001) | 3.03 (2.90 to 3.16) |

| Cancer | 0.1289 (<0.0001) | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.20) |

Logistic regression analysis comparing differences of least square means between each group stratified by number of MetS criteria (zero to four), with Bonferroni adjustment from multiple comparisons, found significantly increased odds of VTE recurrence with each additional MetS component (P < 0.0001). The associated ORs for VTE recurrence based on MetS grouping were as follows: one versus zero MetS components (OR, 2.33; 95% CI, 2.17–2.51), two versus one MetS components (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.56–1.76), three versus two MetS components (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.58–1.76), and four versus three MetS components (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.35–1.56). Furthermore, comparing those patients with all four components versus those with zero components yielded an OR of 9.28 (95% CI, 8.55–10.07) for VTE recurrence.

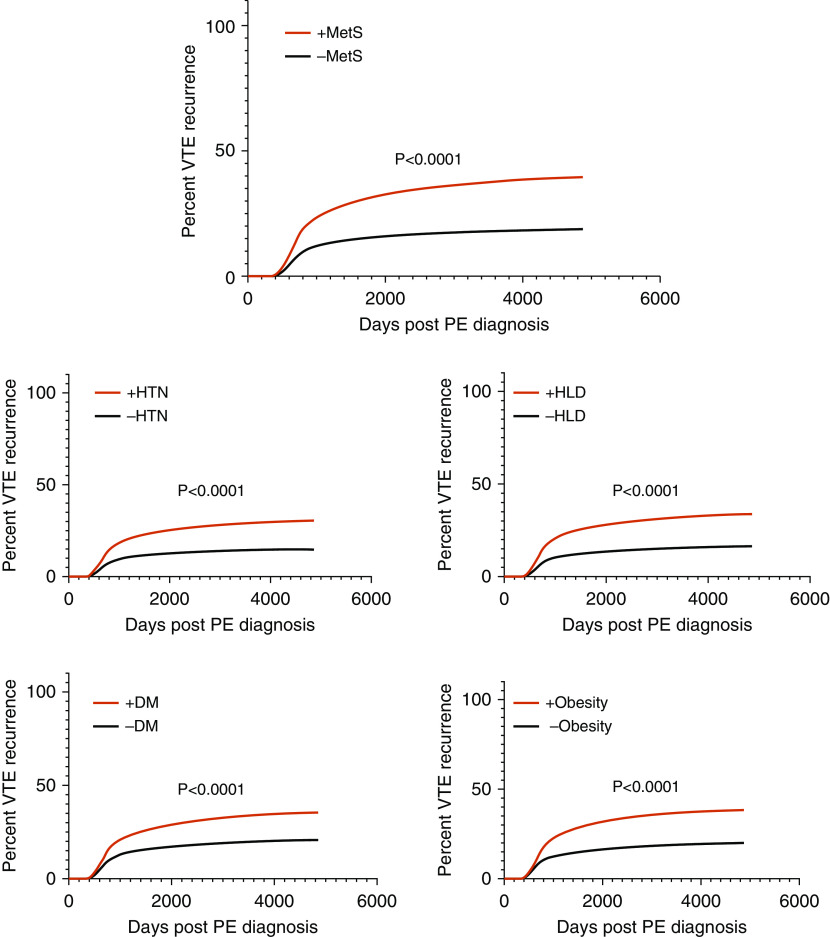

The mean time to VTE recurrence across all patients was +2.6 years after initial index PE date, whereas the mean time to diagnosis of each of the MetS components occurred earlier than that of recurrence. Hypertension diagnosis occurred +0.3 years after index event on average, followed by hyperlipidemia at +0.6 years, obesity at +0.9 years, and diabetes mellitus at +1.0 years. Hazard curve analysis demonstrated significantly (P < 0.0001) increased rates of VTE recurrence across time in patients with each individual component of MetS compared with patients without each of those components. The associated hazard ratios (HRs) were as follows: HR, 2.16 (95% CI, 2.08–2.24) for hypertension; HR, 2.24 (95% CI, 2.16–2.32) for hyperlipidemia; HR, 1.94 (95% CI, 1.87–2.03) for diabetes mellitus; and HR, 2.08 (95% CI, 2.00–2.17) for obesity. Survival analysis was also conducted to compare rates of VTE in patients classified as having MetS (composite +MetS group, requiring at least three of the four MetS components) versus those without MetS. This analysis yielded a significant difference (P < 0.0001) between curves, with an HR of 2.28 (95% CI, 2.19–2.38) for VTE recurrence in the +MetS group. Figure 2 displays the individual Kaplan-Meier curves for VTE recurrence over time based on the presence or absence of each component of MetS, as well as for the composite +MetS group.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for VTE recurrence based on having zero or at least three of the four components of metabolic syndrome, and the individual components. DM = diabetes mellitus; HLD = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; −MetS = zero components of metabolic syndrome; +MetS = at least three of the four components of metabolic syndrome; PE = pulmonary embolism; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

We believe this study to be novel in its overall scope because it examines the role of MetS on VTE recurrence across a large cohort of patients with PE. Whereas prior studies have been limited to retrospective analyses of small databases, our sample included over 72,000 patients with PE, followed for a median time period of approximately 5.5 years, allowing for small CIs. We found the components of MetS to be commonly diagnosed comorbid conditions in patients with PE, with 69% of patients carrying a diagnosis of at least one of these disease processes. Given the methodologic framework of this study, the true prevalence of these MetS conditions in patients with PE may be even higher than we reported because diagnosis was reliant on ICD coding. We found the presence of a composite +MetS profile in patients diagnosed with PE to be associated with significantly greater odds of future VTE recurrence. In developing our DAG model, we postulated a potentially important mediating or confounding effect of several demographic variables and comorbid conditions available in our statewide database, including age, sex, smoking history, atrial fibrillation, COPD, CHF, CKD, anxiety, depression, stroke, MI, and cancer. Of these variables, we determined all but COPD, anxiety, and depression likely influence the outcome variable of VTE recurrence (31–39). These remaining variables were then assessed as either potential mediators or confounders in the relationship between MetS and VTE recurrence. Age, sex, and smoking history were designated as confounders because they influence both MetS and recurrence but do not reside in the causal pathway between these variables. We initially considered CHF, CKD, stroke, MI, atrial fibrillation, and cancer to be potential mediators, at least partially explaining the relationship between MetS and recurrence, and tested the effect of the proposed mediation of each of these factors, as previously described (28–30). The results of this testing supported the mediating role of all proposed variables except for cancer, which was then included in our final model as a confounder due to its established role in VTE recurrence.

The data also showed the novel finding that not only does the presence of each individual component of MetS confer an increased risk of recurrence, the unadjusted frequencies in Table 1 suggest that this risk appears to be summative, increasing the relative probability of VTE recurrence by an additional 50% with each additional MetS criterion. This finding has treatment implications. The stepwise increase in risk implies the opposite: the stepwise removal of each MetS risk factor could cause a 50% reduction in long-term risk of VTE recurrence after PE. Hazard curve plots illustrate the large increase in long-term risk of VTE recurrence caused by the presence of each individual MetS criteria as well as the composite +MetS diagnosis. Moreover, the number of emergency department visits tripled, from 1.2 visits for patients with zero MetS criteria to 3.5 visits with four MetS criteria. This parallel increase in the number of recurrent emergency department visits with each MetS component suggests an increased burden of disease. And, although this work provides no biological mechanism for understanding the risk of VTE recurrence, it does lay the clinical and epidemiological rationale for interventions designed to directly address MetS in patients with new PE diagnosis.

For example, in patients with newly diagnosed VTE, and in addition to appropriate anticoagulation therapy, the implementation of home-based walking programs or cardiac rehabilitation referrals could help reduce the likelihood of future recurrence in at-risk patients. The benefits of exercise are likely mediated across multiple pathways, including increased fibrinolytic capacity due to enhanced endogenous tissue plasminogen activator activity, the reduction of plasma fibrinogen, moderated platelet activity, and decreased circulating inflammatory cytokines (40–43). Furthermore, the initiation of dietary education or targeted pharmacologic agents such as antihypertensive agents, statins, and antihyperglycemic medications may also be of benefit in the emergency department setting (44–46).

This study has several limitations. The patient sample was by INPC policy, therefore precluding true chart review or verification of the accuracy of data extracted. The presence or absence of all components of MetS, as well as VTE and the various other comorbidities of interest, was based solely on ICD-9 or ICD-10 coding, leading to the risk of ascertainment bias. Prior studies have reported ICD codes to demonstrate only a moderate ability to identify VTE, with a positive predictive value of 49% (47). This becomes more challenging when attempting to identify recurrent events, and it is possible that a portion of the recurrences in our dataset could actually represent already existing VTE. It is also possible that these diagnoses may be undercoded or miscoded, and may represent a larger proportion of the study population than what is reported here. Specifically, we noted discrepancies between available patient weight data and a formally coded ICD diagnosis of obesity. For example, only 67% of patients with a weight over 125 kg were coded as obese. It is also possible that patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for these conditions may not have this reflected in their medical record due to health care underutilization before or following time of PE diagnosis. Furthermore, missing data may also occur if patients were seen out of network or out of state, with encounters, therefore, not being captured by the databases included in this analysis. Another important limitation relates to the concept of informed censoring. It is likely that many of the patients currently on treatment for the components of MetS are also the ones who already have these diagnoses coded in the electronic health record, thereby modifying the risk of VTE and leading to potentially biased results. Acknowledging that our database was limited in scope of access to outpatient prescription data, we attempted to compare rates of statin use in patients with and without MetS because statins are the only MetS-related treatment that have been shown to have a substantial effect on VTE recurrence (44–46). We found 24% of patients with MetS to have a documented statin prescription versus 11% of patients without MetS. However, our dataset precludes a true comparison of the impact of treated versus untreated MetS risk factors on VTE recurrence. The lack of hard data, including fasting lipid panels, hemoglobin A1Cs, body mass indices, and blood pressure readings, further limits the overall interpretation of the results. We were also unable to assess the severity of PE and its treatment course, as well as whether this was affected by the presence of the MetS components.

Conclusions

Findings of this large, retrospective study with long-term follow-up suggest the presence of MetS in patients diagnosed with PE to independently increase the risk of VTE recurrence. These results imply a role for increased awareness of MetS risk factors in patients with newly diagnosed PE and the implementation of targeted, adjuvant therapies aimed at reducing recurrence risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Regenstrief Institute Inc. for participation in this project.

Footnotes

Supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) K12 Program in Emergency Care Research (5K12HL133310–03).

Author Contributions: L.K.S. and J.A.K.: responsible for study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Samson SL, Garber AJ. Metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.009. 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassi E, Pervanidou P, Kaltsas G, Chrousos G. Metabolic syndrome: definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 2011;9:48. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltrán-Sánchez H, Harhay MO, Harhay MM, McElligott S. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult U.S. population, 1999-2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Meigs JB. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112:3066–3072. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Morrell CH, Lakatta EG Cardiovascular Health Study. The metabolic syndrome in older individuals: prevalence and prediction of cardiovascular events: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:882–887. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro-Martinez MG, Banderas-Lares DZ, Ramirez-Martinez JC, Escobedo-de la Peña J. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Cir Cir. 2012;80:128–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caballería L, Pera G, Rodríguez L, Auladell MA, Bernad J, Canut S, et al. Metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a Spanish population: influence of the diagnostic criteria used. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1007–1011. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328355b87f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molica F, Morel S, Kwak BR, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Steffens S. Adipokines at the crossroad between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:553–566. doi: 10.1160/TH14-06-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Summer R, Walsh K, Medoff BD. Obesity and pulmonary arterial hypertension: Is adiponectin the molecular link between these conditions? Pulm Circ. 2011;1:440–447. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.93542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Husseny MW, Mamdouh M, Shaban S, Ibrahim Abushouk A, Zaki MM, Ahmed OM, et al. Adipokines: potential therapeutic targets for vascular dysfunction in type II diabetes mellitus and obesity. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:8095926. doi: 10.1155/2017/8095926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stubblefield WB, Alves NJ, Rondina MT, Kline JA. Variable resistance to plasminogen activator initiated fibrinolysis for intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ageno W, Prandoni P, Romualdi E, Ghirarduzzi A, Dentali F, Pesavento R, et al. The metabolic syndrome and the risk of venous thrombosis: a case-control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1914–1918. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang MJ, Choi WI, Bang SM, Lee T, Kim YK, Ageno W, et al. Metabolic syndrome is associated with venous thromboembolism in the Korean population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:311–315. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.184085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vayá A, Martínez-Triguero ML, España F, Todolí JA, Bonet E, Corella D. The metabolic syndrome and its individual components: its association with venous thromboembolism in a Mediterranean population. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011;9:197–201. doi: 10.1089/met.2010.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ay C, Tengler T, Vormittag R, Simanek R, Dorda W, Vukovich T, et al. Venous thromboembolism--a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Haematologica. 2007;92:374–380. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ageno W, Dentali F, Grandi AM. New evidence on the potential role of the metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:736–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borch KH, Braekkan SK, Mathiesen EB, Njølstad I, Wilsgaard T, Størmer J, et al. Abdominal obesity is essential for the risk of venous thromboembolism in the metabolic syndrome: the Tromsø study. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:739–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steffen LM, Cushman M, Peacock JM, Heckbert SR, Jacobs DR, Jr, Rosamond WD, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of venous thromboembolism: Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:746–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldhaber SZ. Venous thromboembolism: epidemiology and magnitude of the problem. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2012;25:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein PD, Matta F, Alrifai A, Rahman A. Trends in case fatality rate in pulmonary embolism according to stability and treatment. Thromb Res. 2012;130:841–846. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prandoni P, Noventa F, Ghirarduzzi A, Pengo V, Bernardi E, Pesavento R, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after discontinuing anticoagulation in patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. A prospective cohort study in 1,626 patients. Haematologica. 2007;92:199–205. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klok FA, van Kralingen KW, van Dijk AP, Heyning FH, Vliegen HW, Kaptein AA, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2010;138:1432–1440. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichinger S, Heinze G, Jandeck LM, Kyrle PA. Risk assessment of recurrence in patients with unprovoked deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: the Vienna prediction model. Circulation. 2010;121:1630–1636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.925214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tosetto A, Iorio A, Marcucci M, Baglin T, Cushman M, Eichinger S, et al. Predicting disease recurrence in patients with previous unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a proposed prediction score (DASH) J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1019–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lederer DJ, Bell SC, Branson RD, Chalmers JD, Marshall R, Maslove DM, et al. Control of confounding and reporting of results in causal inference studies. Guidance for authors from editors of respiratory, sleep, and critical care journals. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:22–28. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-564PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suttorp MM, Siegerink B, Jager KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW. Graphical presentation of confounding in directed acyclic graphs. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1418–1423. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enga KF, Rye-Holmboe I, Hald EM, Løchen ML, Mathiesen EB, Njølstad I, et al. Atrial fibrillation and future risk of venous thromboembolism:the Tromsø study. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:10–16. doi: 10.1111/jth.12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rinde LB, Småbrekke B, Mathiesen EB, Løchen ML, Njølstad I, Hald EM, et al. Ischemic stroke and risk of venous thromboembolism in the general population: the Tromsø study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(11):e004311. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cimminiello C, Filippi A, Mazzaglia G, Pecchioli S, Arpaia G, Cricelli C. Venous thromboembolism in medical patients treated in the setting of primary care: a nationwide case-control study in Italy. Thromb Res. 2010;126:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dean SM, Abraham W. Venous thromboembolic disease in congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16:164–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wattanakit K, Cushman M, Stehman-Breen C, Heckbert SR, Folsom AR. Chronic kidney disease increases risk for venous thromboembolism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:135–140. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rinde LB, Lind C, Småbrekke B, Njølstad I, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, et al. Impact of incident myocardial infarction on the risk of venous thromboembolism: the Tromsø Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:1183–1191. doi: 10.1111/jth.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson FA, Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23, Suppl 1):I9–I16. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078469.07362.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barco S, Klok FA, Mahé I, Marchena PJ, Ballaz A, Rubio CM, et al. RIETE Investigators. Impact of sex, age, and risk factors for venous thromboembolism on the initial presentation of first isolated symptomatic acute deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2019;173:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McRae S, Tran H, Schulman S, Ginsberg J, Kearon C. Effect of patient’s sex on risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:371–378. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eliasson M, Asplund K, Evrin PE. Regular leisure time physical activity predicts high activity of tissue plasminogen activator: The Northern Sweden MONICA Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:1182–1188. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.6.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.el-Sayed MS. Effects of exercise on blood coagulation, fibrinolysis and platelet aggregation. Sports Med. 1996;22:282–298. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199622050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stratton JR, Chandler WL, Schwartz RS, Cerqueira MD, Levy WC, Kahn SE, et al. Effects of physical conditioning on fibrinolytic variables and fibrinogen in young and old healthy adults. Circulation. 1991;83:1692–1697. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.5.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lakoski SG, Savage PD, Berkman AM, Penalosa L, Crocker A, Ades PA, et al. The safety and efficacy of early-initiation exercise training after acute venous thromboembolism: a randomized clinical trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1238–1244. doi: 10.1111/jth.12989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez AL, Wojcik BM, Wrobleski SK, Myers DD, Jr, Wakefield TW, Diaz JA. Statins, inflammation and deep vein thrombosis: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;33:371–382. doi: 10.1007/s11239-012-0687-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams NB, Lutsey PL, Folsom AR, Herrington DH, Sibley CT, Zakai NA, et al. Statin therapy and levels of hemostatic factors in a healthy population: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1078–1084. doi: 10.1111/jth.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt M, Cannegieter SC, Johannesdottir SA, Dekkers OM, Horváth-Puhó E, Sørensen HT. Statin use and venous thromboembolism recurrence: a combined nationwide cohort and nested case-control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1207–1215. doi: 10.1111/jth.12604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Ani F, Shariff S, Siqueira L, Seyam A, Lazo-Langner A. Identifying venous thromboembolism and major bleeding in emergency room discharges using administrative data. Thromb Res. 2015;136:1195–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.