Abstract

Rationale: Expansion of chronic ventilation options and shared decision-making have contributed to an increasing population of technology-dependent children. One particularly vulnerable group is children with tracheostomy who depend on technology for basic respiratory functions. Chronic critical care is now provided in the homecare setting with implications for family caregivers.

Objectives: This study explores the experience of family caregivers of children and young adults with a tracheostomy during the transition from hospital to home care. We sought to identify the specific unmet needs of families to direct future interventions.

Methods: We recruited a convenience sample of families from an established home ventilation program to participate in semistructured interviews. Sessions were conducted in person or via teleconference. A grounded-theory qualitative analysis was performed.

Results: Between March 2017 and October 2018, we interviewed 13 individuals representing 12 families of children and/or young adults with tracheostomy. Patients ranged in age from 9 months to 28 years, had a tracheostomy for 8 months to 18 years, and represented a variety of underlying diagnoses. Five key themes emerged: 1) navigating home nursing; 2) care coordination and durable medical equipment (DME) impediments; 3) learning as a process; 4) managing emergencies; and 5) setting expectations.

Conclusions: Our findings support the need for family-centered discharge processes including coordination of care and teaching focused on emergency preparedness.

Keywords: experience, family, tracheostomy, home care, qualitative

There is a growing population of children with chronic complex conditions cared for at home with supportive technologies (1). An increasingly complex and vulnerable subgroup is children and young adults with tracheostomy. The underlying indications for tracheostomy are varied and often multifactorial, including airway obstruction, chronic lung disease, neuromuscular insufficiency, aerodigestive compromise, and need for long-term mechanical ventilation (2).

Successful transition of a technology-dependent child from the hospital to the community involves adapting the home environment to provide for the child’s physical needs, training family caregivers and homecare providers, and accessing additional support resources (3, 4). Provision of routine and, potentially, emergency care for the child with chronic respiratory failure have both emotional and practical implications for home caregivers (5). Parental preparation for this transition typically includes education with a range of didactic teaching, review of print and electronic educational materials, side-by-side demonstration, and teach-back methods. Accepted standards implemented at many institutions include demonstrating competency with specific skills, low-fidelity simulation for cardiopulmonary resuscitation training, and 24-hour-care rehearsals (6, 7). A greater understanding of knowledge and skill gaps, as well as barriers to their implementation in the community, is critical to prevent and mitigate complications.

Surveys of families caring for children with tracheostomy have reported varied perceptions of the quality of care coordination and predischarge training, and their overall preparedness for discharge (8, 9). Qualitative investigations have explored the moral and social experience of families (10–12). Common themes have included coping with the responsibility of becoming a medical provider, adapting the home environment and family life, experiencing social isolation, and striving to maintain quality of life for the child.

This study builds on existing literature with a focus on understanding the learning and transitional process for families of children/youth with a tracheostomy. Determining actionable areas for improvement in training and support of home caregivers would inform hospital-based clinicians, whose a priori ideas may not fully represent the lived experience in the community. Therefore, we undertook this study to identify the specific unmet training needs for families and other home caregivers.

Methods

Study Design

To maximize the range of perspectives by reducing barriers to participation, such as distance from the hospital and/or the daily demands of providing care, we conducted focus groups and interviews either in person or via teleconference (13). The interview mode was chosen by each participant.

Setting and Participants

The population of interest was family caregivers of children and young adults cared for at home with a tracheostomy. Participants were recruited from the C.A.P.E. (Critical Care, Anesthesia, Perioperative Extension, and Home Ventilation) Program (14) at Boston Children’s Hospital, a quaternary freestanding children’s hospital with 404 inpatient beds, performing approximately 60–75 tracheostomies annually. The C.A.P.E. Program follows approximately 300 patients, 121 with a tracheostomy. Eligible participants had a living child at home with a tracheostomy and a working knowledge of English or Spanish. We mailed prospective participants an invitation letter with a postage-paid, preaddressed opt-out card. In this convenience sample, we intentionally sampled for diversity in geographic location, payer status, and underlying condition to reflect a range of experiences. Recruitment continued until we reached thematic saturation (Appendix E1).

Interview Guide Development

We developed an interview guide by a multidisciplinary iterative process (Appendix E2). We revised the proposed questions in two planning discussions with physicians, respiratory therapists (RTs), nurse educators, child life specialists, and behavioral and qualitative researchers. Open-ended questions were included to encourage exploration of issues experienced in the community, training needs for home caregivers, barriers to safe care, and identification of opportunities within the healthcare system to optimize routine care and response to emergencies. The breadth of these questions sought to elicit issues that were meaningful to participants. We did not pilot test the interview guide and no revisions were made after initial use.

Data Collection and Management

To reduce bias, sessions were facilitated by an RT (M.H.H.) and physician (L.G.A.-D.) researcher with no longitudinal clinical relationship to participants. Field notes were taken during each session. Audio and video recordings of in-person meetings were stored on a secure server accessible only to the research team. Remote interviews were conducted using the Zoom platform, a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant service using end-to-end 256-bit advanced encryption standard (AES) encryption (Zoom Video Communications, Inc., 4.1.23501.0416 ed.). Video and audio recordings were transcribed by our study coordinator (M. Morrissey) and then reviewed and edited by an investigator (L.G.A.-D.) for accuracy before analysis.

Analysis

We used a grounded-theory approach to develop broader themes from our data (15). Transcripts were analyzed to group-related concepts, and a coding dictionary (Appendix E3) was generated based on the key content of the interviews using the Dedoose web application (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, version D. 8.2.14). Working independently, a physician investigator (L.G.A.-D.) and a qualitative research professional (S. Christensen) coded the interviews. Code applications were periodically clarified through review of coding discrepancies, and additional codes were generated as new common themes emerged. Recruitment was concluded when saturation of key themes was reached. A third physician reviewer (R.J.G.) participated in final coding, arbitrated discrepancies, and added additional codes, which were reviewed by primary coders.

This research was approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written, signed informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Results

Of the 33 families contacted, 15 expressed interest, 1 was not interested, and 17 did not respond; 12 families (represented by 13 individuals) were able to complete the sessions, whereas 3 interested families were unable to schedule an interview before the study’s conclusion. All participants were primarily English speaking. Families represented children with a variety of diagnoses, aged 9 months to 28 years, with a tracheostomy present for 8 months to 18 years (Table 1). Five children/youths were receiving continuous mechanical ventilation, three were receiving part-time mechanical ventilation, two were not receiving mechanical ventilation, and two had undergone tracheostomy decannulation. Participants included 10 mothers, 1 father, and 1 young adult with a tracheostomy. Each participating family was interviewed in a single session.

Table 1.

Study participants

| Patient Age | Sex (M/F) | Support | Time with Tracheostomy (Time from Discharge) | Indication for Tracheostomy (Diagnostic Category) | Family Member | ID | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 yr | M | Ventilator intermittent | 18 yr (17 yr) | Cerebral palsy (mixed neurologic and CLD) | Mother | 1 | In-person focus group |

| 5 yr | F | Tracheostomy only decannulated | 2 yr (4 yr) | Neuroblastoma (acquired upper airway obstruction) | Mother | 2 | In-person focus group |

| 7 yr | F | Ventilator | 4 yr (4 yr) | Brain tumor (neurologic) | Mother | 3 | In-person interview |

| 13 yr | F | Ventilator | 13 yr (12 yr) | Cerebral palsy (mixed neurologic and CLD) | Father | 4 | In-person interview |

| 28 yr | M | Ventilator | 3 yr (3 yr) | Muscular dystrophy (myopathic) | Mother/Patient | 5/6 | Video focus group |

| 5 yr | M | Ventilator overnight | 4 yr (4 yr) | CHD (acquired upper airway obstruction) | Mother | 7 | Video interview |

| 5 yr | M | Ventilator | 5 yr (5 yr) | Myopathy (myopathic) | Mother | 8 | Video interview |

| 9 mo | M | Tracheostomy only | 8 mo (4 mo) | Chronic lung disease (CLD) | Mother | 9 | Video interview |

| 2 yr | M | Ventilator intermittent | 1 yr (1 yr) | Acute flaccid myelitis (neurologic) | Mother | 10 | Video interview |

| 3 yr | M | Tracheostomy only | 3 yr (3 yr) | CHD (Mixed acquired upper airway obstruction, CLD) | Mother | 11 | Video interview |

| 6 yr | M | Ventilator decannulated | 3 yr (5 yr) | CPAM (mixed acquired upper airway obstruction, CLD) | Mother | 12 | Video interview |

| 1 yr | F | Tracheostomy ventilator | 1 yr (7 mo) | Chromosomal abnormality (neurologic) | Mother | 13 | Video interview |

Definition of abbreviations: CHD = congenital heart disease; CLD = chronic lung disease; CPAM = congenital pulmonary airway malformation; F = female; M = male.

We conducted two focus groups of two individuals and nine individual interviews. Sessions lasted 28–74 minutes. A total of 117 pages of single-spaced transcripts was generated (6–14 pages/interview). Few novel domains were generated after coding the ninth session. Field notes revealed comparable impression about the emotional tone and candor of the interviews and focus groups. Five common themes emerged as experiential phenomena for parents of children with tracheostomy. Each theme is presented below with unedited supporting quotations from participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Themes and representative quotations

| Theme | Quotation (Ref.) |

|---|---|

| 1. Navigating home nursing | |

| It was a blessing and a curse…I remember his primary nurses continuously saying I know you can do it, but you can’t do it every single day and every single night. You need to have some sort of break. (12) | |

| It’s hard finding nurses. And then the nurses would come and be like “oh yeah I know what I am doing,” and then you find out like no, she doesn’t have a clue. And the companies want you to teach them. And I’ll teach them and they end up leaving so it’s really stressful. (4) | |

| It’s good to keep a nurse for years and years and years. It’s very helpful. (6) | |

| Relying on other people for the welfare of your child is a really really hard thing to deal with. Especially when your child is their job but he’s your child. (8) | |

| One of the things I struggle with is that we trust our nurses, otherwise we wouldn’t leave them alone with our child. But the nursing agency, at least from what I understand, they don’t have emergency training...I think my husband and I are feeling right now, there is a lot of blind trust happening with our nurses. (9) | |

| They have to become part of your family, they have to fit with the personality of your daughter or son, they have to fit with the rest of the family. I don’t really care what experience they come with now. Because we have had girls right out of nursing school that come with no experience. I look for the fit, first. (3) | |

| You want to direct them, but you feel bad. I felt very vulnerable, because they are in my home. And we’re sleeping and you know you pray that all the right background check and training has happened but you are never quite sure…I guess if there were some tips to empower parents. You get to be the boss, you get to set limits, because I did feel like a lot of it was out of my control. We were dependent on this…these services. (2) | |

| They were sending them out to homes and not fully ready for what they had to take care of. (7) | |

| 2. Care coordination and DME | |

| They gave us a list of all the nursing agencies and the supply companies. Who do we go with? I remember being like, I don’t know who to pick and being stressed out about that and supplies…It is all that stress on top of caring. (3) | |

| I came home to a home that I almost didn’t know. It was so foreign to me at that point in time. During all that time, we were getting deliveries for supplies, things I didn’t understand...It was just a crazy experience to come home. You have this dream of bringing your baby home for the first time, and it’s an ambulance ride, you are ambushed by the DME, the respiratory therapist. You are walking into a house where you just don’t know where anything is. (11) | |

| I remember it as this whirlwind of like someone was there from the company that did the oxygen and the concentrators…I have this memory of the house being full of people dropping stuff off. And sort of not knowing who any of them were…when the calm happened we asked each other “do you know what that one does?”...you would have stuff that didn’t go anywhere. (2) | |

| And it is so exhausting having to have battles each and every day in trying to keep your child healthy and at home and safe. They just, they didn’t understand. (12) | |

| The supplies, the ventilators, the suction machines, the mist machines, everything was hugely overwhelming. (1) | |

| [T]o have them come and do training in your home on the equipment you will be given would be very helpful. (8) | |

| Yeah, the day that we got home they had dropped off a bunch of medical supplies, but they hadn’t hooked up the ventilator tubes. So we got [our son] home and we were all excited and ready to put him on the vent at night and I was like “I have no idea how to do this. I don’t know what pieces we need.” And the pieces they gave us were the wrong pieces and we didn’t know what to do, which was not a good situation. (10) | |

| Logistically, also trying to figure out whether we set up his room correct and whether there were certain things we would need. What was the best way of making sure the vent was mobile and the suction was mobile too. Like sorting out all of that stuff was stressful at first. (9) | |

| It’s so hard. It is so hard. You have to give yourself an extra hour no matter where you are going. (13) | |

| 3. Learning as a process | |

| [T]he nurses really cared about making sure we felt completely comfortable. We were trained very well…as time has gone on, it’s just become a part of life and trach changes used to send me into cardiac arrest and now we do them every other week and it’s very regular routine now. In the beginning it was pretty tough. (7) | |

| I can tell you, I talk about it now that is just the way of life, but back then…I just remember like having to do trach cares…which was something I dreaded every day. She would desat, she would turn blue…Now she is helping pull her trach out and wants to put it in when we do trach changes. So, yeah we have come a long way. (3) | |

| Coming home, of course emotionally it was really exciting to get him out of the hospital but also terrifying because it was the first time where we were independently caring for him. (9) | |

| The trach, as scary as it is, it saved my son’s life…It was a very hard decision to come to, but it was the best decision we ever made for him. And he like turned the corner so quickly, just with that because he could breathe. (1) | |

| We go everywhere, that’s what I tell people. The vent, obviously it’s not ideal to have it but you know what, I feel 100% better since getting it. I have a little more energy and it’s a lot more portable. (6) | |

| We have taken him to the beach when he was on all these things. It is all possible…Those are all things that I think we didn’t realize were possible until we saw other parents doing it. And until you are kind of encouraged to say, hey you know what, this is what is medically recommended and every child is different. But push the envelope a little bit so your child has some normalcy because he deserves it. (11) | |

| 4. Managing emergencies | |

| You just don’t know what to do. That is the hardest thing about home care. You just don’t know what you are going to run into, you don’t know what’s going to happen next. (1) | |

| I wish that we had been better prepared for an emergency situation. Yes, you can talk to them all day long and you could say to me “What would you do if this happened?” but that’s not really enough. (13) | |

| There are scenarios, when you are completely caught off guard, what happens when you walk into a room and your child is not responsive…it’s just very different when you get hospital training than what you are dealing with it in the home. (11) | |

| I felt probably less confident about it because we didn’t practice in a realistic manner or in an emergency scenario. (9) | |

| Now I know how you guys feel about when something goes down and all your schooling hits you, stuff’s flying through your head, you’re trying to grasp information, you kind of feel like a doctor at that point. (4) | |

| [M]ore simulated stuff so that parents can see what can happen when a baby is in distress—to show what a plug looks like, to show what it sounds like, what it sounds like for a trach to fall out, maybe situations like that. (7) | |

| Those real-life emergency scenarios. We hadn’t even touched upon…I share that information with any new trach families I come across so they don’t have to experience some more controllable situations. If we can control a situation in a very uncontrollable story line than that is always better. (12) | |

| 5. Setting expectations | |

| It would have been scary, but I would have loved somebody to do that. This isn’t elective, like you have to do it. So I would have rather had someone tell me like “this is how hard it is, it is really hard”. My husband and I talk about it, were like that part was worse, not I shouldn’t say worse than cancer, but it was harder in a lot of ways. (2) | |

| [W]e’ve learned when we talked to other families what you should tell them and what you shouldn’t tell them because everybody experiences things differently and we wouldn’t want to frighten anybody who’s any more frightened than they already are. (5) | |

| I would have loved to talk to somebody before going home. Just to know, you can’t just grab the baby and go someplace. (1) | |

| I think the biggest shock coming home was just all of the other pieces that you have to manage that you just don’t think of. (10) | |

| I had never been told about tracheitis. I now know it is very common, but being readmitted after 4 1/2 mo in NICU, I felt like such a failure…that was disappointing because I just felt like I failed [my son] and was questioning my confidence in taking care of him. (12) | |

| I think that warning me ahead of time. I knew that there would be a lot. But I guess when you’re in the hospital and coming home to all of this, like I don’t think that you could ever really prepare for the amount of supplies you’re bringing somebody home to. (13) | |

| [T]he internet is great, but nothing compares to actually meeting another family face to face and seeing how things are set up…just seeing someone else how they use the vent and trach in home and how they manage things. That I think was the most helpful. (8) | |

| He was talking and eating and everything. I remember seeing that and thinking okay pretty soon I’ll be able to do that. So that was helpful meeting someone…We would just email them and talk about that stuff a couple times. It’s not easy, but there’s nothing to be afraid of. It’s not easy, but eventually you get through it. You can be more, not independent, but not tethered to like a bypass machine. It’s incredibly portable, we go on bike trails, I went up to the top of Mount Washington. (6) | |

| There are so many things that I wish I could tell them so that I could help, at least paint a picture for the future for them. Hey listen, this is my kid, he didn’t have the greatest story but look at where he is now. But at the same time, if anyone dumped the amount of information that I know now, to the person that I was 2 yr ago, I wouldn’t have been able to handle or understand it. (11) | |

| There was an attending…and he told us on one of our multiple readmissions that first year that the first year would be awful, really bad, and the second year would be bad but not as awful. And the third year would start to get a little better and it was the first time any doctor actually said it was going to be bad. It was very blunt and it was exactly what we needed to hear because it was exactly true…It’s nice being on the other side for sure. (7) | |

| I was already scared…It would have been good if I had saw or had more…all the parents like have coffee time, whatever. And it’s good just to talk like this, you know what I mean? You get different ideas…No, it was kind of like I was on an island by myself...It would have kind of prepared me for all of that stuff. I think I lost a couple years off my life from all the stress. (4) |

Definition of abbreviations: DME = durable medical equipment; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Navigating Home Nursing: It Was a Blessing and a Curse

Nearly every family we interviewed had experiences with homecare nurses. Many described a tension between the dawning recognition that they could not be the sole care providers, citing the need for physical assistance and respite, and the challenges of having nurses in their home. Families noted significant challenges obtaining insurance approval for “adequate” home nursing hours and subsequent difficulty finding nurses to fill approved hours. This experience varied by state of residence; families living outside Massachusetts described greater difficulty filling approved nursing hours. The young adult participant reported less difficulty finding and retaining home nursing. Additional challenges included loss of control and privacy, difficulty entrusting care to strangers, and concerns about the training and skills of nurses. Families expressed an initial expectation that nurses would impart additional medical knowledge and skills. However, parents soon found themselves taking on the educator role for their child’s routine and emergency care. Multiple families expressed frustration at the high rate of nurse turnover after investing considerable time training nurses in their child’s care. Retention of home nurses required trust, which was predicated on perceived competence, acknowledgment that the child was the foremost consideration, reliability, and compatibility, or “fit,” with their family.

Care Coordination and Durable Medical Equipment Impediments: It Is All that Stress on Top of Caring

All families worked with durable medical equipment (DME) companies for provision of medical supplies and equipment. Many described competing time demands as a stressor at discharge. In particular, families described the challenges of navigating concurrent conflicting demands: to be at the hospital training or participating in their child’s care, and to be at home receiving equipment deliveries and training on new equipment. Families reported being overwhelmed by the number of supplies and lack of guidance on the setup and organization of this equipment. Families described unreliable or incomplete communication between providers regarding their child’s care plan and goals when transitioning from acute care to rehabilitation or home care. Once home, coordinating and advocating for necessary equipment contributed additional stress and detracted from their ability to focus on their child’s direct care. Families reported problems with fractured communication, with little clarity about whom to contact regarding broken equipment, specific medications, and nutritional provisions. Families commonly perceived that DME company representatives did not comprehend the urgency of addressing equipment failures.

Learning as a Process: Look Where We Are Now

Most families reported adequate preparation for their child’s routine care. They described graded exposure to care, with hands-on training by RTs and bedside nurses. Training techniques included: 1) using an inert doll with a tracheostomy to increase familiarity with the tracheostomy and with changing of the tracheostomy tube and securement ties; 2) participating in suctioning and tracheostomy changes on their child; and 3) spending a period of time when they were responsible for all aspects of their child’s care before leaving the hospital. Training duration and location were highly variable depending on the child’s illness trajectory. Teaching occurred in the intensive care unit, on medical and surgical wards (for nonventilated patients), in rehabilitation hospitals, and, at times, in the home by DME company representatives. Parents cited the importance of being pushed outside their comfort zone and remaining engaged in their child’s care during their time in the hospital. Most reported minimal opportunities to use their child’s home equipment before they were discharged, and they appreciated any opportunities for hands-on training that were available at the hospital or rehabilitation facility. During the initial stages of taking on the caregiver role, many families described feelings of fear and isolation, but recalled increased confidence as they acquired experience. As they became more secure in providing direct care and navigating the healthcare system after discharge, families regained a sense of normalcy and increased participation in their communities. Having achieved a level of comfort themselves, several families felt motivated to help new families beginning this transition process.

Managing Emergencies: You Just Don’t Know What to Do

Despite feeling prepared for the routine care of their child, many parents cited a gap between the idealized version of tracheostomy care presented during hospital training and the practical realities of care in the home. They described feeling unprepared for emergencies such as manual bagging and emergency tracheostomy changes. Teaching around emergency care was limited to cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for most participants, although some families described hospital-based providers providing didactic teaching that prompted them to think through the steps of managing an emergency. Unanticipated challenges included learning skills in the hospital on equipment different from the equipment they would use at home, uncertainty about how to prioritize cleanliness versus timeliness in an emergency, how to arrange equipment in the home to facilitate an emergency response, and how to troubleshoot malfunctioning equipment. Parents recounted specific medical emergencies they experienced at home, including problems with the tracheostomy site or tube, suction and/or ventilator failure, intercurrent infection, seizures, and medication errors (Table 3)—all of which may have been easier to manage with more training on these specific issues. Many participants cited the importance of informal education from other families and support systems. Online communities, in particular, played a key role in bridging the gap between the hospital teaching and the realities of homecare. Many felt that exposure to common emergency scenarios with organized instruction and feedback on how to respond would have been helpful. Some reported that greater knowledge of basic anatomy and physiology would have helped them respond to emergencies and allay fears that their interventions could cause injury.

Table 3.

Home care emergencies experienced by participants

| Emergency | Description |

|---|---|

| Tracheostomy | |

| Mucus plug | |

| Positional tracheostomy occlusion | |

| Accidental decannulation | |

| Desaturation with tracheostomy changes | |

| Respiratory distress | |

| Skin breakdown at stoma | |

| Bloody secretions | |

| Equipment problems | |

| Desaturation on ventilator | |

| Ventilator disconnection | |

| Ventilator failure | |

| Ventilator circuit failure | |

| Ventilator battery failure | |

| Suction machine failure | |

| Kinking of oxygen tubing | |

| Humidification failure | |

| Aspiration from ventilator circuit | |

| Infections | |

| Increased secretions | |

| Tracheitis | |

| Pneumonia | |

| Stoma infection | |

| Other | |

| Seizures | |

| Medication errors | |

| Power outage | |

| Running out of oxygen | |

| Forgotten equipment | |

| Dehydration |

Setting Expectations: This is How Hard It Is, It Is Really Hard

Although participants represented a range of diagnoses, clinical trajectories, and illness severities, each reported that the experience of transitioning to home was more difficult than they had anticipated. The unanticipated complexities of home care left families feeling overwhelmed by the demands of care coordination. They experienced fear, self-doubt, and loss of control when entrusting the well-being of their child to medical technology and home nurses. Some families observed that transparency from medical providers about the challenges of caring for a child with a tracheostomy helped normalize their experience. Some acknowledged the importance of presenting a realistic view of the road ahead while taking care to not overwhelm or frighten families. Several participants felt that, because their child needed the tracheostomy, they would have preferred to have had as much information as possible; they felt that increased anticipatory guidance could attenuate self-doubt when common clinical scenarios arise. Those who reported feeling most prepared had the opportunity to meet with the family of another child with a tracheostomy in their community. Forming relationships with other families, in person and online, facilitated the sharing of advice on purchasing and arranging medical equipment, anticipating complications, preparing for emergencies, navigating school and community support systems, and developing workarounds for unreliable communication within and from the healthcare system.

Discussion

This investigation adds to the existing literature describing families’ transition from the hospital to home after their childrens’ tracheostomies. Five key themes emerged from our interviews: navigating home nursing; care coordination and DME impediments; learning as a process; managing emergencies; and setting expectations. We believe our findings may inform the training processes in pediatric healthcare settings where families are trained to care for their child with new technology support needs. Modifications in traditional training techniques would be an important step toward optimizing both medical and psychosocial outcomes.

Families participating in our study described a complex health services landscape encompassing education from multiple hospital units, rehabilitation hospitals, outpatient providers, home nursing, and DME companies. Current practices of graded exposure to technical health care procedures were perceived as effective for learning skills necessary for routine care. However, families described a gap between the idealized hospital training and the real-life situations faced at home. Families increasingly relied on other families through direct connections and social media platforms. The fear and self-doubt that families described on the initial transition home only changed into confidence through experience. This learning process is in keeping with the model of “wayfinding” for family caregivers, in which concentrated support from healthcare professionals occurs early in the process with increasing self-reliance and individual ownership of the care over time (16). Viewing our family caregivers in this way, we may seek to maximize the gain from the early stages of this process and foster connections that may contribute to later stages of learning.

Respiratory emergencies are a key aspect of home care for which families felt underprepared. Families reported that crisis training tended to be didactic, if it occurred at all. If safety and anticipatory care are to evolve for this at-risk population, comprehensive preparation of both family members and home care providers should more closely emulate the state-of-the-art critical event management training that is currently offered to hospital-based providers (17). This use of simultion to optimize the response to high-impact, low-frequency events offers a model for preparing families and community providers. Medical simulation takes advantage of adult learning principles and aligns with principles of patient- and family-centered care by building on existing strengths and encouraging collaboration (18). A number of published reports have demonstrated the feasibility of using high-fidelity simulation to train families of children with chronic illness (19, 20), including those requiring long-term mechanical ventilation. These studies have demonstrated an improvement in caregiver confidence and preparedness, and may have an impact on hospital readmissions (21–24).

Patient- and family-centered medical simulation will require consideration of participant health literacy and the psychosocial stress of caring for a loved one. Curricula could incorporate a common core with dynamic, patient-specific content to respond to individual technical and emotional needs. Simulation curricula may include equipment setup and troubleshooting, routine and emergency airway management, and crisis resource management modules to better equip families to manage the complex needs of their child. As with medical professionals, postsimulation debriefing appears to be an essential component of effective simulation training for family caregivers (24).

One major challenge described by families was home nursing. Existing literature has described gaps in the home care infrastructure, including the lack of adequate home health staffing and qualified pediatric nurses (25, 26). Successful relationships with home nurses appeared to be built on trust, investment in learning the child’s care, and compatibility with the family and their routines. This mirrors what parents have described as their ideal in home nursing—technical competence, caring, ceding control of care to the parents, and fitting in with the family (27, 28). In addition to a shortage of pediatric home nurses, participants expressed concern about nurse competence and training. Pediatric homecare nurses caring for children with mechanical ventilation have shown poor performance in case-based emergency scenarios and report a need and desire for more crisis-management training (29). Homecare agencies, typically, do not have the training infrastructure of hospital systems; therefore, as pediatric centers with expertise in supportive technologies become the default medical home for children with medical complexity, there is an opportunity to leverage hospital resources to educate families and homecare providers to smooth this transition home (30). As simulation technology becomes more portable and accessible, there are opportunities for outreach providing mobile training to homecare agencies, acute and rehabilitation hospitals, and even in the home with native teams of family and nursing caregivers.

Family caregivers in our study described being overwhelmed by demands of home setup, care coordination, medical equipment, and time. They expressed a belief that calibrating expectations about these difficulties could help prepare families and normalize their experience. A published analysis of meetings in which healthcare providers counseled families on indications for tracheostomy found that physicians may emphasize benefits over risks in these discussions (31). Several families in our interviews reported feeling that they did not have a viable alternative to choosing tracheostomy. As such, participants valued greater transparency and anticipatory guidance from providers about the realities of homecare despite concerns that this information may be overwhelming. This finding is consistent with a recently published analysis of parental decision-making about initiating mechanical ventilation (32). After tracheostomy, connections with other families were perceived as helpful in understanding and navigating the challenges of home care. Though challenging with respect to selection bias during the initial tracheostomy decision-making process, institutional efforts to connect families may be particularly useful in discharge preparation. Promising future areas include using web platforms to design spaces for home care with augmented reality and offering a view into the homes of other families to share information about setup, organization, and safety procedures.

As has been described previously (8, 33), families reported loss of information about care plans and goals in transitions from ambulatory, inpatient, and home care settings. Families employed self-devised work-arounds to bridge these gaps in electronic and interpersonal communication. This additional burden may be alleviated by information management systems that facilitate sharing medical information and care plans across care domains.

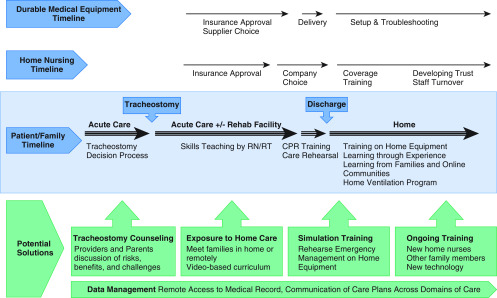

Multiple interdependent elements of discharge planning compete for the time and attention of families during a period when it is critical that they acquire training in key aspects of their child’s care. The discharge process requires the alignment of the child’s medical stability with caregiver readiness, insurance approval of nursing hours and medical equipment, delivery of medical equipment, training on home equipment, subsequent staffing of nursing hours, and preparation of the home environment (Figure 1). These nonmedical factors can delay discharge for children with medical complexity (34). Families view their inpatient time as invaluable to their preparation for care at home (35). Improved integration of these systems would allow families to use this in-hospital time to learn both routine care skills and crisis management approaches with the equipment they will use at home. Broader implementation of the American Thoracic Society guidelines regarding care coordination, caregiver training, and equipment for children with chronic home invasive ventilation could address many of the issues raised here (3). Discharge preparedness should include strategies to ensure that the correct equipment is delivered to the home, properly set up, and arranged in an optimal layout. In addition, if the timeline of home nurse staffing were appropriately aligned with discharge planning, there could be opportunities for nurses and families to partner effectively and learn together about the child’s specific care needs.

Figure 1.

Reconstruction of discharge experience, challenges, and potential solutions. This timeline is constructed from participant interviews representing the transitional experience of families (triple line light blue box) from before tracheostomy to after discharge home. Parallel durable medical equipment (DME) and home nursing timelines are depicted (single lines) that do not optimally align with the family timeline. In particular, delays in approval and filling of nursing hours, as well as the timing of DME delivery just before—or coincident with—discharge contribute to family stress. Green boxes represent opportunities to address barriers to successful transition home, including initial counseling, graded exposure to homecare, approaches to caregiver training, and communication with multiple providers. Improved remote access to the electronic health record (including summary medical history, recent diagnostics, and clear contacts for specific condition and medication questions) for families, home care, and community providers has the potential to decrease information loss and the need for work-arounds. CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; RN = registered nurse; RT = respiratory therapist.

Limitations

This study included a small number of families in a single geographic region and institution. The perspectives represented are primarily those of mothers, and only those who chose and were able to participate. However, each participant represents a rich experience, and our findings are in keeping with those of other qualitative and quantitative work with similar populations. The broad range of diagnoses and time since tracheostomy may be considered both a strength and a limitation; there is a risk of recall bias, but also the opportunity to understand the longitudinal process of transitioning home. Our institution has made coordinated efforts to standardize discharge education (7), and participants were recruited from a program designed to support complex home care. The families included would be expected to have more support in the transition home than those without access to these services. Thus, these findings likely underrepresent the challenges faced by some families at our institution and others.

Conclusions

The five key themes that we identified in our interviews could serve to inform future interventions to train and support families during the discharge process. We propose medical simulation with home equipment as an opportunity to prepare families to operate in the home environment, as well as integrate the skills of families and home care nurses for routine and emergency care. Advocacy efforts should support the infrastructure of home nursing and coordination with DME companies to access equipment earlier for training and setup purposes. Information management systems should share information and care plans across institutions, including home care providers. Connecting families in person and using web-based platforms for information sharing may help with adaptation to the realities of home care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the families who participated in this work, the medical providers and educators who care for the children, and the following individuals who contributed their work to this project: Sinead Christensen, M.P.H.; Kelsey Graber, M.S.; Katherine Jamieson, M.P.H.; Maura Morrissey, B.A.; Lauren Perlman, R.R.T.; and David Williams, Ph.D.

Footnotes

Supported by the Boston Children’s Hospital Accountable Care Organization, Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Innovation Grant, and by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality award T32HS000063.

Author Contributions: L.G.A.-D. and R.J.G.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and final approval of the manuscript. M.H.H.: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and writing and final approval of the manuscript. B.O’C., S.K.P., C.J.R., and P.H.W.: conception and design, and writing and final approval of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Downes JJ. The future of pediatric critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(Suppl):S307–S310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199309001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry JG, Graham DA, Graham RJ, Zhou J, Putney HL, O’Brien JE, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes and hospital resource use of children after tracheotomy. Pediatrics. 2009;124:563–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, Carroll JL, Sharma GD, Brozek JL, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e16–e35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0276ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell RB, Hussey HM, Setzen G, Jacobs IN, Nussenbaum B, Dawson C, et al. Clinical consensus statement: tracheostomy care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:6–20. doi: 10.1177/0194599812460376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartnick CJ, Bissell C, Parsons SK. The impact of pediatric tracheotomy on parental caregiver burden and health status. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1065–1069. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.10.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartnick C, Diercks G, De Guzman V, Hartnick E, Van Cleave J, Callans K. A quality study of family-centered care coordination to improve care for children undergoing tracheostomy and the quality of life for their caregivers. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;99:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells S, Shermont H, Hockman G, Hamilton S, Abecassis L, Blanchette S, et al. Standardized tracheostomy education across the enterprise. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;43:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormick ME, Ward E, Roberson DW, Shah RK, Stachler RJ, Brenner MJ. Life after tracheostomy: patient and family perspectives on teaching, transitions, and multidisciplinary teams. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:914–920. doi: 10.1177/0194599815599525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pritchett CV, Foster Rietz M, Ray A, Brenner MJ, Brown D. Inpatient nursing and parental comfort in managing pediatric tracheostomy care and emergencies. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:132–137. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnevale FA, Alexander E, Davis M, Rennick J, Troini R. Daily living with distress and enrichment: the moral experience of families with ventilator-assisted children at home. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e48–e60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callans KM, Bleiler C, Flanagan J, Carroll DL. The transitional experience of family caring for their child with a tracheostomy. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenner M, Larkin PJ, Hilliard C, Cawley D, Howlin F, Connolly M. Parents’ perspectives of the transition to home when a child has complex technological health care needs. Int J Integr Care. 2015;15:e035. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nehls K, Smith BD, Schneider HA.Video-conferencing interviews in qualitative research Hai-Jew S.editor. Enhancing qualitative and mixed methods research with technology. Hershey, PA: Business Science Reference, an imprint of IGI Global; 2015140–157. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham RJ, McManus ML, Rodday AM, Weidner RA, Parsons SK. Pediatric specialty care model for management of chronic respiratory failure: cost and savings implications and misalignment with payment models. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19:412–420. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald J, McKinlay E, Keeling S, Levack W. The ‘wayfinding’ experience of family carers who learn to manage technical health procedures at home: a grounded theory study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31:850–858. doi: 10.1111/scs.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roussin CJ, Weinstock P. SimZones: an organizational innovation for simulation programs and centers. Acad Med. 2017;92:1114–1120. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:626–632. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Lee M, Johnson K. Development and pilot testing of a parent education intervention for type 1 diabetes: parent education through simulation-diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38:50–57. doi: 10.1177/0145721711432457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigalet E, Cheng A, Donnon T, Koot D, Chatfield J, Robinson T, et al. A simulation-based intervention teaching seizure management to caregivers: a randomized controlled pilot study. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:373–378. doi: 10.1093/pch/19.7.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tofil NMRC, Rutledge C, Zinkan JL, Youngblood AQ, Stone J, Peterson DT, et al. Ventilator caregiver education through the use of high-fidelity pediatric simulators: a pilot study. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013;52:1038–1043. doi: 10.1177/0009922813505901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold J, Diaz MC. Simulation training for primary caregivers in the neonatal intensive care unit. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40:466–472. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raines DA. Simulation as part of discharge teaching for parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2017;42:95–100. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thrasher J, Baker J, Ventre KM, Martin SE, Dawson J, Cox R, et al. Hospital to home: a quality improvement initiative to implement high-fidelity simulation training for caregivers of children requiring long-term mechanical ventilation. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hefner JL, Tsai WC. Ventilator-dependent children and the health services system: unmet needs and coordination of care. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:482–489. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201302-036OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobotka SA, Gaur DS, Goodman DM, Agrawal RK, Berry JG, Graham RJ. Pediatric patients with home mechanical ventilation: the health services landscape. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54:40–46. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendes MA. Parents’ descriptions of ideal home nursing care for their technology-dependent children. Pediatr Nurs. 2013;39:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nageswaran S, Golden SL. Factors associated with stability of health nursing services for children with medical complexity. Home Healthc Now. 2017;35:434–444. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kun SS, Beas VN, Keens TG, Ward SS, Gold JI. Examining pediatric emergency home ventilation practices in home health nurses: opportunities for improved care. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50:691–697. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster CC, Agrawal RK, Davis MM. Home health care for children with medical complexity: workforce gaps, policy, and future directions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:987–993. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hebert LM, Watson AC, Madrigal V, October TW. Discussing benefits and risks of tracheostomy: what physicians actually say. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:e592–e597. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards JD, Panitch HB, Nelson JE, Miller RL, Morris MC. Decisions for long-term ventilation for children: perspectives of family members. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:72–80. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201903-271OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, Putney H, Helm D, O’Brien J, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobotka SA, Hird-McCorry LP, Goodman DM. Identification of fail points for discharging pediatric patients with new tracheostomy and ventilator. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6:552–557. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham RJ, Pemstein DM, Curley MA. Experiencing the pediatric intensive care unit: perspective from parents of children with severe antecedent disabilities. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2064–2070. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a00578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.