Abstract

Rationale: Medical interventions that prolong life without achieving an effect that the patient can appreciate as a benefit are often considered futile or inappropriate by healthcare providers. In recent years, a multicenter guideline has been released with recommendations on how to resolve conflicts between families and clinicians in these situations and to increase public engagement. Although laypeople are acknowledged as important stakeholders, their perceptions and understanding of the terms “potentially inappropriate” or “futile” treatment have received little formal evaluation.

Objectives: To evaluate the community perspective about the meaning of futile treatment.

Methods: Six focus groups (two groups each of ages <65, 65–75, and >75 yr) were convened to explore what constitutes futile treatment and who should decide in situations of conflict between doctors and families. Focus group discussions were analyzed using grounded theory.

Results: There were 39 participants aged 18 or older with at least one previous hospitalization (personal or by immediate relative). When asked to describe futile or inappropriate treatment, community members found the concept difficult to understand and the terminology inadequate, though when presented with a case describing inappropriate treatment, most participants recognized it as the provision of inappropriate treatment. Several themes emerged regarding participant difficulty with the concept, including inadequate physician–patient communication, lack of public emphasis on end-of-life issues, skepticism that medical treatment can be completely inappropriate, and doubts and fears that medical futility could undermine patient and/or family autonomy. Participants also firmly believed that in situations of conflict families should be the ultimate decision-makers.

Conclusions: Public engagement in policy development and discourse around medical futility will first require intense education to familiarize the lay public about use of inappropriate treatment at the end of life.

Keywords: intensive care unit, potentially inappropriate treatment, end-of-life care, community

The concept of medical futility is controversial and widely debated among healthcare professionals (1–3), legal consultants (4, 5), and bioethicists (6–8). Key stakeholders, patients, and families have played little role in this debate. Consideration of the patient/family perspective is increasingly important because health care has shifted from a disease-centered model to a patient-centered model whereby patients and families are empowered to actively engage and participate in the decisions that affect their care (9).

In 2015, the American Thoracic Society, American Association for Critical Care Nurses, American College of Chest Physicians, European Society for Intensive Care Medicine, and Society of Critical Care Medicine released a multisociety statement recommending that the term “potentially inappropriate” be used instead of “futile” and for institutions to resolve differences between clinician recommendations and patient/family wishes using a detailed conflict resolution process (10). Furthermore, the statement recommends partnering with the public to develop policies and legislation because “the boundaries of acceptable medical practice require value judgments that go beyond the expertise of clinicians,” and because key stakeholders, patients, and their families will be the ones to experience the effects of such policies (10, 11).

Although laypeople are acknowledged as important stakeholders, their perceptions and understandings of the terms “potentially inappropriate” or “futile” treatments have received little formal evaluation. Previous studies have either broadly explored patients’ opinions about life-sustaining treatments at the end of life (EOL) (12, 13) or focused on asking patients about the utility of particular interventions in specific health states (i.e., resuscitation in advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) (14, 15). Before engaging the public in this area of policy development, it is important to ascertain the public’s understanding of potentially inappropriate treatment. This study’s goal was to use focus group interviews with community-dwelling adults to gain insight into the public’s understanding about the concept and implications of potentially inappropriate/futile treatment.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board (#17–001698), and all focus group participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Participants were recruited via email distributed to an academic medical center’s volunteer and patient–family advisory council electronic mailing list. The email asked for interest in participating in a focus group to share opinions on being a patient or family member of a patient; a consent form was attached that stated we were seeking perspectives of non–healthcare providers on the topic of inappropriate treatment, also known as futile care. A flyer was also placed in the volunteer office. Inclusion criteria were age 18 or older, English-speaking, and personal history of hospitalization or an immediate relative with previous hospitalization). Interested participants contacted the principal investigator (T.H.N.), who confirmed eligibility. Participants received a $25 gift card and parking validation.

Focus Groups

Focus groups were stratified by age (two groups each of participants age <65, 65–75, and >75 yr) because age has been shown to be a predictor of decision-making (16–18). Each session convened for approximately 90 minutes in a conference room in an academic health center, and were digitally recorded, transcribed, and anonymized before analysis. At the end of each session, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

Two physician-investigators experienced in facilitating focus groups (T.H.N. and D.M.T. or T.H.N. and N.S.W.) led discussions using a semistructured interview protocol (Table 1). T.H.N. is a critical care physician-researcher, D.M.T. is a family physician with expertise in provider–patient communication, and N.S.W. is an internist and ethics expert whose research has focused on EOL care. Questions focused on soliciting participant understanding about the concept of futile care, including what it means, who should decide if treatment is futile/inappropriate, and what happens if disagreements occur. For ease of communication, we primarily used the term “medical futility” (older, more common, and easily understood term) (6, 8) instead of “potentially inappropriate treatment” (newer, officially recommended term) (3, 9) during the focus group discussions, and participants were asked to voice perspectives on both terms. The facilitators subsequently provided a clinical scenario describing a patient receiving futile treatment for discussion. The scenario is presented as follows: “Let’s think about a 90-year-old patient with end-stage cancer in an intensive care unit (ICU). This woman has cancer everywhere. She’s attached to a machine that breathes for her, and she’s on a dialysis machine that does the job for her kidneys. She’s not able to eat or talk, and does not recognize or interact with the people around her. The doctor says the patient will likely die within one week, no matter what treatment she gets.” This scenario was used to explore participants’ views regarding futile care and how disagreements between family preferences and physician recommendations should be resolved.

Table 1.

Focus group questions

| 1. First, let’s go around the room: introduce yourself and state whether you have heard about the term “futile care.” |

| 2. Keeping in mind that the topic of this discussion goes by multiple terms, tell us what comes to mind when you think of “futile or non-beneficial or inappropriate treatment” in the hospital? |

| 3. What do you believe it means to receive treatment or care that is no longer meaningful? |

| 4. Tell me about an experience you’ve had, or one that you heard or read about, in which someone received futile/inappropriate care. |

| 5. Facilitator gives example of futile treatment. Do you think this case represents medical futility/inappropriate treatment? Why or why not? |

| 6. Who gets to decide whether a treatment is futile/inappropriate? |

| 7. If patients/family members and doctors disagree about giving certain treatments to a hospitalized patient, how should they handle these disagreements? |

| 8. What things (if any) make it ok to not do everything possible to keep a patient alive? |

Qualitative Analysis

Researchers used grounded theory (19) to iteratively analyze transcripts and inductively generate thematic categories regarding participants’ understanding and views of medical futility and treatment decision-making. To enhance the trustworthiness of data analysis, T.H.N. and C.L.P. (a nurse researcher) independently performed inductive line-by-line coding (20) to develop initial thematic categories that were grounded in participants’ descriptions, and met to discuss themes and adjudicate discrepancies. Codes representing generated themes were refined, split, and merged, and a codebook was developed. Two other investigators, D.M.T. and N.S.W., examined the codes and coding categories to ensure analytic validity. T.H.N. then performed focused coding using the codebook and maintained detailed notes about analytic decisions. During analysis, no notable differences surfaced among the different focus groups, and focus group transcripts were therefore analyzed in aggregate. The qualitative software program ATLAS.TI 8 (Scientific Software Development) was used for analyses.

Results

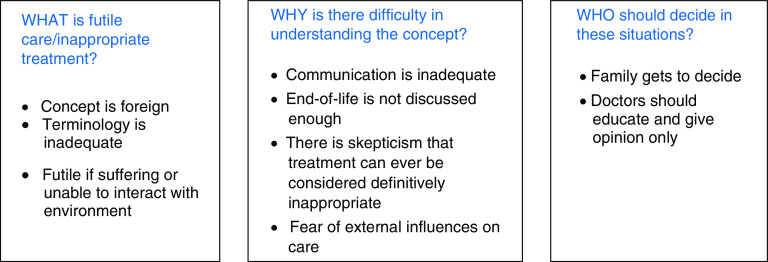

Thirty-nine community members participated in six focus groups (5–8 participants per group). The average age was 68 ± 9.7 years (range 47–86 yr) and 30 (77%) were female, 31 (79%) were white, and 35 (90%) had at least completed college (Table 2). Qualitative analysis revealed themes that answered the following questions: what is the meaning of futile treatment, why does the lay public have difficulty understanding the concept, and who should decide about the care that is provided in these situations? (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Participants, N | 39 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 68 (9.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 30 (77) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 31 (80) |

| Asian | 2 (5) |

| Black | 2 (5) |

| Other | 4 (10) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic (vs. non-Hispanic) | 1 (2.6) |

| Religion, n (%) | |

| Christian/Catholic | 20 (51) |

| Jewish | 12 (31) |

| Religious science | 1 (3) |

| None | 6 (15) |

| Is religion important to you?, n (%) | |

| Not at all | 9 (23) |

| Somewhat | 13 (33) |

| Very | 17 (44) |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | |

| Less than high school | 0 |

| High school graduate | 1 (2.5) |

| Some college | 2 (5) |

| College graduate | 14 (36) |

| Postgraduate education | 21 (54) |

| Missing | 1 (2.5) |

| Participant hospitalized before, n (%) | 39 (100) |

| Participant has had family hospitalized, n (%) | 38 (97) |

Definition of abbreviation: SD = standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Themes revealed during qualitative analysis of focus group discussions on futile care.

What Is Futile/Inappropriate Treatment?

Most participants had not heard of the terms futile or inappropriate treatment before and the concept was foreign. With further discussion, several participants agreed that treatment that caused suffering without achieving a meaningful recovery was inappropriate. One participant gave an example of a neonate with severe brain damage who was being kept alive on machines and stated, “I would see it as prolonging suffering.” However, 27 (69%) participants had never heard of the term “futile care.” When asked to provide examples of cases where continued care might be futile, some participants described situations in which clinicians elected to provide highly aggressive, life-saving interventions in hopes of achieving recovery. This sharply contrasts with cases that clinicians typically consider as medically futile. One participant described a situation in which a patient was kept alive with intravenous inotropes in the ICU as he waited for a heart transplant. Another participant described how a patient survived cardiopulmonary resuscitation and received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, stating that some might have considered the situation futile. These participants indicate that using high-intensity interventions in critical situations could be viewed by some as futile. Clinicians, however, may characterize these interventions as high-risk and aggressive but not futile (i.e., they believe that the chances of a good outcome are high enough to justify these aggressive measures).

Several focus group participants conveyed that the existing terminology was inadequate: “I thought it [the term futile care] was more like accusatory…just mean spirited. Didn’t find it helpful, thought it was like name calling.” Many participants believed that the term “potentially inappropriate” brought more confusion, rather than clarity, because for many, “inappropriate” was synonymous with providing the wrong treatment or “malpractice.” One participant commented, “If a diabetic comes in and they think the best course of treatment is to remove her leg because it’s gangrenous… but she gets another [opinion and] they said, ‘no, we only have to remove part of your foot, we don’t have to remove your leg.’ To me, if she had gotten the full leg removed it would have been inappropriate treatment.”

Why Does the Lay Public Have Difficulty Understanding the Concept of Futile/Inappropriate Treatment?

Communication is inadequate

Participants pointed out that lay persons often have difficulty understanding physicians: “[Physicians] say things that might be over your head and we just needed somebody to break it down for us.” One participant thought audio recorders would be helpful so that families can repeatedly listen to important conversations at their own pace. Another participant suggested that a navigator might be helpful: “One would think, there might be some sort of a trained person who would be available to be consulted . . . for the kind of discussion we’re talking about. To help evaluate . . . What does this information mean?” Participants noted that patients and families often do not comprehend what physicians say, such that the nuanced concept of whether a treatment is potentially inappropriate would likely be hard to understand.

EOL is not discussed enough

Participants pointed out that the topic of futile care reminded them that we live in a society where advance care planning is not done frequently and in which “We don’t talk about dying.” As such, EOL preferences are not discussed, which sometimes leads to EOL care that is fraught with conflict and treatments that are not concordant with a patient’s values and preferences. Participants also recognized that EOL discussions often come too late: “That’s why it’s so important to intercede early on, in an ideal system. But we don’t have that.” Participants agreed that stakeholder engagement and open discussions about medical futility were important: “[Take] the issue, futile care, and just hit it from all sides, not one particular one. Just hitting it from every direction you can. Facilitate the forms, facilitate the dialogue, put it into medical school, put it into nurses’ training . . . Just bombard it from all sides.”

Skepticism that medical treatment can ever be definitely futile

Multiple participants expressed doubt about whether medical care can be unequivocally futile. Participants stated that these opinions are perspective-dependent: “Futile is in the mind of the beholder” and that “If you have a loved one that is fighting, you might not consider that futile at all.” Furthermore, participants in every focus group wanted to discuss the exception—a case in which the healthcare team considered treatment to be futile and yet ended in miraculous recovery (i.e., a comatose patient waking up despite the physician’s prognostication).

Fear of external influences on care

Some worried that the term inappropriate treatment was used for insurance purposes and were wary of ulterior motives for overriding family decisions. A participant voiced fears that doctors will use the concept of futility to justify limiting care and increasing profit margins: “You always think of those conspiracy theories like ‘doctors are only doing it for the insurance money,’ you know, that’s all they care about.” Given insurance and other economic pressures, participants believed it was difficult for healthcare providers to make decisions that were purely based on patients’ best interests.

Who Should Decide in Situations with Potentially Inappropriate Treatment?

In situations of conflict, families get to decide

Although some participants mentioned conflict resolution processes (i.e., ethics committee, judicial processes), the overarching belief was that families (and patients, if possible) should be the ultimate decision-makers in situations in which there was conflict between a family’s wishes and the clinical team’s recommendations. One participant described medical decision-making as being a fundamental American right: “In the United States, I think it should be up to the patient. Different country, different beliefs, England, Canada, or something, it’s different, but I thank God we’re here and I think it’s up to the family or the patient to do it.” A distinct minority (3 participants across all focus groups) felt that physicians should be the ones who made the decision because they would more likely be impartial; as one participant explained, “I would say, personally, I would want the doctors to make the decision, not my family, because I personally don’t want to suffer.”

Participants also articulated fears that the concept of medical futility would undermine patient/family autonomy. The thought of physicians using the concept of futility to justify withholding treatments was concerning to many. One participant stated that if a hospital can decline a requested treatment, this would cause patients and families to “lose our democratic way. Then the states are picking our human rights.”

Physician role is limited (primarily to inform families)

Participants believed it was important for physicians to be honest and provide guidance but that families should make the ultimate, independent decision. One participant explained, “The doctor should just give out all the information. All the facts, just like you said, and then step back and the families should make the decision. It’s their family. It’s their lives.” Another participant stated, “If we allow a process where others get to make the decision as to whether or not we live or die, it’s going to be driven more and more, and more, and more by the cost”; again emphasizing the concern that decisions are driven by exterior motives and less likely in the patient’s best interest if anyone besides the family gets to decide.

When facilitators presented a clinical scenario that most clinicians would consider to be potentially inappropriate treatment (90-yr-old with widely metastatic cancer), participants uniformly agreed that continued aggressive treatment was inappropriate: “I would let her go, make her comfortable.” The conversation reveals that participants are able to understand how a treatment can be considered inappropriate but also that participants believe that the family is able to opt for such treatments if they choose:

- Facilitator: [Presents scenario of comatose 90-year-old with end-stage cancer on life support]Should she be continued on machines?

- Participant 1:Nope . . . I’d take her off immediately.

- Participant 2:I think humans are entitled to part without the trauma of the medical interventions that are keeping them alive.

- Facilitator:They [the family] want to keep her on the machines.

- Participant 2:I assume that the doctor has to agree to that.

- Facilitator:Is her care futile?

- Participant 2:Absolutely, yes. I would say that unequivocally, yes.

- Participant 3:It’s invasive, and useless.

- Facilitator:The doctors say to the family, “This is inappropriate treatment, we should stop it now.” And the family says, “No. We want to keep on going.” Whose choice is it?

- Participant 2:It’s the family’s.

- Participant 1:Yeah, it’s the family. It’s got to be the family’s.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that members of the lay public have difficulty understanding or articulating the concept of medical futility. The purpose was to deduce what public engagement would add to the futility dialogue and policy development, which was suggested by a multisocietal consensus statement that proposed national guidelines for cases of potentially inappropriate medical treatment and recommended engagement of the public (10). In these focus groups, community members agreed they should be involved in this discourse but also frequently expressed misconceptions about the concept, a distrust toward the medical field that influenced their perspectives, and a firm belief that families should be the ultimate decision-makers.

The lack of understanding regarding this topic appears to partly stem from the inadequacy of the language that is used to specify this concept. Semantics matter (21) but our current vocabulary does not facilitate a clear understanding of the topic. Furthermore, as some bioethicists have claimed, the recommended change in terminology from futile to potentially inappropriate may have only made it more difficult for community stakeholders to grasp (22). As such, before bringing the public to the table in a dialogue that will shape policy and legislation, the lay public needs to be educated about the issues that come into play in situations regarding potentially inappropriate treatment.

Our qualitative work also revealed that community members can exhibit cognitive dissonance, the condition where two inconsistent beliefs are held simultaneously (23, 24), which will unlikely be addressed by conventional education. When focus group facilitators presented a case of a 90-year-old unconscious, imminently dying patient being kept alive on machines at the request of the family, several participants wholeheartedly agreed that the situation represented inappropriate treatment and that the patient should be transitioned to comfort care. The same participants also were adamant that families should be the sole decision-makers in situations of conflict, and subsequently expressed fears of losing autonomy. Research in cognitive dissonance indicates that when individuals experience the uncomfortable tension of holding two inconsistent beliefs (25), their natural reaction is to try to reduce the dissonance by using self-justification and defensive reasoning, which can in turn further escalate and distort their thinking (23, 26). Similarly, prior research in the ICU revealed that a surrogate’s misinterpretations of a physician’s prognostication are often explained by emotional and optimistic biases rather than a misunderstanding of the data (27). It is important to recognize and attend to these complex cognitive biases because they can prevent objectivity.

In addition, our study reveals that members of the lay public strongly believe in patient autonomy and are often skeptical when the medical field recommends a reduction in treatment intensity. Given society’s inherent inequities, these community members’ perspectives appear to be shaped by fears of being rendered powerless in decision-making and suspicions that medical decisions are motivated by profit margins. Recently, a survey study showed that disclosure of information about a detailed process for the decision to withhold life-sustaining treatments was correlated with an increase in public acceptance of the determination of medical futility (28). As we move forward with engaging the public in changes in policy and legislation, spreading awareness about the use of second opinions and transparency in due-process will need to be prioritized. This will likely require considerable education in deliberative focus groups, which is part of the process by which democratic citizens can make justifiable societal decisions despite fundamental disagreements that are inevitable in diverse populations (29).

The potential for researcher bias is a limitation of this analysis but was minimized in this study by having researchers of different training and backgrounds conduct focus groups and perform independent coding of transcripts, remaining firmly grounded in participants’ descriptions, and detailing analytic decisions, which were reviewed by team members. Other study limitations include recruitment of focus group participants from a convenience sample of one medical center’s volunteers and patient–family advisory council members. The majority of our participants were white and, therefore, did not represent the diversity that currently exists among the American public. Because perspectives and preferences regarding EOL communication and decision-making differ among race and ethnic groups (30), our findings may be limited. Participants were also college educated and thus may be more educated than the majority of Americans. The finding that inadequate understanding and cognitive dissonance currently exist about the concepts of futile/potentially inappropriate treatment among a group of highly educated individuals supports the need for public-friendly language and education.

Conclusions

Public engagement in policy development and discourse around medical futility will require intense education to familiarize the lay public of the issues at hand, as well as an awareness of the accompanying cognitive biases that will likely follow. More work is needed on how to introduce the concept of potentially inappropriate treatment and orient families to the concept before shared decision-making in these situations is requested.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author Contributions: T.H.N. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, and for drafting of the manuscript. T.H.N., D.M.T., and N.S.W. were responsible for the study concept, design, and data collection. T.H.N., D.M.T., C.L.P., and N.S.W. were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data, and for critical revision of manuscript.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Palda VA, Bowman KW, McLean RF, Chapman MG. “Futile” care: do we provide it? Why? A semistructured, Canada-wide survey of intensive care unit doctors and nurses. J Crit Care. 2005;20:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrell BR. Understanding the moral distress of nurses witnessing medically futile care. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:922–930. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.922-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kon AA, Shepard EK, Sederstrom NO, Swoboda SM, Marshall MF, Birriel B, et al. Defining futile and potentially inappropriate interventions: a policy statement from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1769–1774. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope TM. Legal briefing: futile or non-beneficial treatment. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22:277–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren DG. The legislative role in defining medical futility. N C Med J. 1995;56:453–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneiderman LJ, Faber-Langendoen K, Jecker NS. Beyond futility to an ethic of care. Am J Med. 1994;96:110–114. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson DJ, Savulescu J. Knowing when to stop: futility in the ICU. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:160–165. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328343c5af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneiderman LJ. Defining medical futility and improving medical care. J Bioeth Inq. 2011;8:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s11673-011-9293-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinpell R, Zimmerman J, Vermoch KL, Harmon LA, Vondracek H, Hamilton R, et al. Promoting family engagement in the ICU: experience from a national collaborative of 63 ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1692–1698. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, Lo B, Truog RD, Rushton CH, et al. ; American Thoracic Society ad hoc Committee on Futile and Potentially Inappropriate Treatment; American Thoracic Society; American Association for Critical Care Nurses; American College of Chest Physicians; European Society for Intensive Care Medicine; Society of Critical Care. An official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM policy statement: responding to requests for potentially inappropriate treatments in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1318–1330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0924ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veatch RM. Generalization of expertise. Stud Hastings Cent. 1973;1:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez KL, Young AJ. Perceptions of patients on the utility or futility of end-of-life treatment. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:444–449. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez KL, Young AJ. Patients’ and healthcare providers’ understandings of life-sustaining treatment: are perceptions of goals shared or divergent? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris WM, Nielsen EL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Treatment preferences for resuscitation and critical care among homeless persons. Chest. 2005;127:2180–2187. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, Collier AC. The attitudes of patients with advanced AIDS toward use of the medical futility rationale in decisions to forego mechanical ventilation. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1597–1601. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covinsky KE, Fuller JD, Yaffe K, Johnston CB, Hamel MB, Lynn J, et al. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Communication and decision-making in seriously ill patients: findings of the SUPPORT project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S187–S193. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin FC, Laux JP. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nogami N, Nakai K, Horimoto Y, Mizushima A, Saito M. Factors affecting decisions regarding terminal care locations of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. doi: 10.1177/1049909119901154. [online ahead of print] 23 Jan 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miles M, Huberman M, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kon AA. Futile and potentially inappropriate interventions: semantics matter. Perspect Biol Med. 2018;60:383–389. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2018.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneiderman LJ, Jecker NS, Jonsen AR. The abuse of futility. Perspect Biol Med. 2018;60:295–313. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2018.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein J, McColl G. Cognitive dissonance: how self-protective distortions can undermine clinical judgement. Med Educ. 2019;53:1178–1186. doi: 10.1111/medu.13938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croyle RT, Cooper J. Dissonance arousal: physiological evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;45:782–791. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.45.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruppen LD, Margolin J, Wisdom K, Grum CM. Outcome bias and cognitive dissonance in evaluating treatment decisions. Acad Med. 1994;69(Suppl):S57–S59. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199410000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zier LS, Sottile PD, Hong SY, Weissfield LA, White DB. Surrogate decision makers’ interpretation of prognostic information: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:360–366. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailoor K, Valley TS, Kukora S, Zahuranec DB. Explaining the process of determining futility increases lay public acceptance. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:738–743. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201811-790OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gutmann A, Thompson D. Why deliberative democracy? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shrank WH, Kutner JS, Richardson T, Mularski RA, Fischer S, Kagawa-Singer M. Focus group findings about the influence of culture on communication preferences in end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:703–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.