Abstract

Background

Ototoxicity may interact with the effects of aging, leading to a more severe hearing loss than that associated with age alone. The purpose of this study was to explore the associations between ototoxic medication use and the incidence and progression of hearing loss in older adults with a population-based longitudinal study.

Methods

Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study participants (n = 3,753) were examined. Medication use was assessed using a standardized questionnaire by the examiners at each examination every 5 year. The ototoxic medications include loop diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, chemotherapeutic agents, quinine, and acetaminophen in this study. Generalized estimating equations model was used as a proportional hazard discrete time analysis.

Results

Number of ototoxic medications was associated with the risk of developing hearing loss during the 10-year follow-up period (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06, 1.25) after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, and body mass index. Loop diuretics (HR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.05, 1.87) were associated with the 10-year incidence of hearing loss. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (HR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.22, 1.72) and loop diuretics (HR = 1.33 95% CI = 1.08, 1.63) were associated with risk of progressive hearing loss over 10 years.

Conclusion

These ototoxic medications are commonly used in older adults and should be considered as potentially modifiable contributors to the incidence and severity of age-related hearing loss.

Keywords: Medication, Hearing loss, Risk factors

Hearing loss is a common sensory deficit among older adults (1), and age is the most common factor associated with its development (2). An analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that more than two-thirds of adults more than 75 years old have hearing loss (3). However, both age and exposure to life experiences that damage the ear contribute to the development of age-related hearing loss (4). Sex and race may also contribute to the differences in the prevalence of hearing loss found among individuals, and the cumulative effects of extrinsic damage and/or intrinsic diseases may accelerate age-related changes in the auditory system (5,6).

The results of ototoxicity also may interact with the changes that occur with aging, leading to a more severe hearing loss than that associated with age alone (7). Ototoxicity is defined as cellular degeneration in the inner ear caused by a drug’s side effects (8). However, the association between ototoxic drugs and age-related hearing loss has not been consistently found. Although review articles state that ototoxic medications frequently cause hearing loss in older adults (1,9), there is little epidemiological evidence to support this conclusion. Most studies of medication-related hearing loss have been conducted involved children or animal models. The majority of animal studies were conducted to determine the mechanisms underlying ototoxicity in the ear and the results may not be easily transferable to humans (10). In addition, although the short-term ototoxic effects of medications are relatively well documented and generally known to clinicians, the long-term consequences of ototoxic drug use have not been adequately studied.

The purpose of this study was to examine the association between ototoxic medication use and the 10-year cumulative incidence and progression of hearing loss in older adults.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

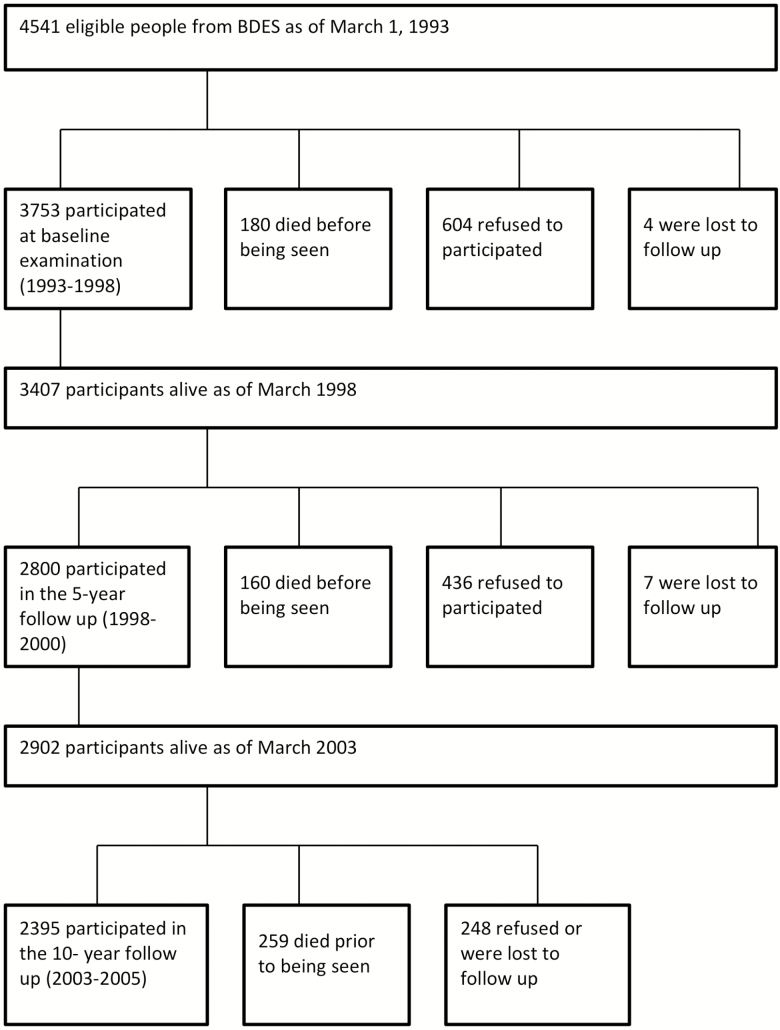

This study was conducted using selected variables extracted from the ongoing longitudinal Beaver Dam Eye Study and the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study (EHLS) data sets. Researchers conducting the Beaver Dam Eye Study identified individuals 43–84 years of age from a private census conducted during 1987 and 1988 in Beaver Dam Wisconsin and invited them to participate in a study of age-related ocular disorders (11). The Beaver Dam Eye Study participants alive as of March 1, 1993 were eligible for baseline examination for the EHLS (12). This cohort was examined in 1993–1995 (n = 3,753), 1998–2000 (n = 2,800), and 2003–2005 (n = 2,395) with a high follow-up rate among living participants (Figure 1) (13,14). Cohort and follow-up characteristics according to differences between participants and nonparticipants have been published previously (13,14).

Figure 1.

At baseline, 1,955 participants in the EHLS had normal hearing and were, therefore, at risk of developing incident hearing loss by the follow-up examinations. Participants who had mild-to-moderate hearing loss at baseline were included for evaluating the progression of hearing loss (n = 1,439).

The study was approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin and signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants at baseline and follow-up examinations. This study received a waiver of review from the Human Research Protection Program Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco because only de-identified data were used.

Measures

Ototoxic medication use

Medication use among the EHLS participants was obtained from the concurrent Beaver Dam Eye Study examination of the same cohort (15). Medication use was assessed using a standardized questionnaire administered by the examiners at each data collection point every 5 years (16). Participants were asked to bring all prescription and over-the-counter medications that they were regularly taking at least once per week. The examiner recorded the medication from the label on the bottle and checked whether the medication bottle was the correct one for the medicine the participant reported taking. The examiner also asked whether there were other medications being taken that were not brought to the interview. If so, the interviewer then phoned the participant at home to have the participant read the name of the medication over the phone. When necessary to verify medication and reason for use, the examiner phoned the participants, their physicians, and/or their pharmacies. In addition, EHLS participants were asked whether they had a history of hospitalization with fever requiring intravenous antibiotics and if they had a history of receiving chemotherapy. If yes to the latter, they were asked about the type of chemotherapy received, duration of chemotherapy, and age at first chemotherapy.

Medications selected for this study and defined as “ototoxic medications” here were those that have been identified as ototoxic in the literature reviewed (1,9). These included loop diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics, chemotherapeutic agents, quinine, and acetaminophen. Concomitant ototoxic medications were considered if a participant was taking more than one ototoxic medication.

Outcome

Incidence of hearing loss and severity of hearing loss were the main dependent variables. Hearing loss was defined as a pure tone average (PTA) at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz greater than 25 dB HL (decibels hearing level) in either ear. The grades of hearing loss and their impact on performance are presented in Table 1. The participants with hearing loss at baseline were considered to be at risk of hearing loss progression. Progression of hearing loss was defined as a PTA at 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz in either ear at any follow-up that was equal to or greater than 10 dB HL above baseline PTA among those who had mild-to-moderate hearing loss (25 dB HL < PTA ≤ 60 dB HL).

Table 1.

WHO Grades of Hearing Loss

| Grade of loss | Audiometric value (average of 500, 1,000, 2,000, 4,000 Hz) | Loss description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (Normal) | 25 dB HL or less | No or very slight hearing problems. Able to hear whispers |

| 1 (Slight loss) | 26–40 dB HL | Able to hear and repeat words spoken in normal voice at 1 m |

| 2 (Moderated loss) | 41–60 dB HL | Able to hear and repeat words using raised voice at 1 m |

| 3 (Severe loss) | 61–80 dB HL | Able to hear some words when shouted into better ear |

| 4 (Profound loss including deafness) | 81 dB HL or greater | Unable to hear and understand even a shouted voice |

Source: World Health Organization (WHO) Report of the Informal Working Group on Prevention of Deafness and Hearing Impairment Program Planning

To evaluate hearing, pure-tone air-conduction and bone-conduction audiometry were used in the three EHLS cycles. Pure-tone air-conduction thresholds were measured by clinical audiometers for each ear at 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, 4,000, 6,000, and 8,000 Hz in sound-treated booths according to the guideline (17). Masking was used when necessary.

At the baseline examination, Virtual 320 clinical audiometers (Virtual Corporation, Seattle, WA) equipped with TDH-50P earphones and insert earphones (Cabot Safety Corp., Indianapolis, IN) were used. At the follow-up examinations, GSI 61™ clinical audiometers (Grason-Stadler, Inc., Madison, WI) equipped with TDH-50P earphones and insert earphones were used. Participants unable to travel to the clinic site were tested using a Beltone 112 portable audiometer (Beltone Electronic Corp., Chicago, IL). All audiometers were calibrated every 6 months during the study periods according to American National Standards Institute standards (18,19). Ambient noise levels were obtained at each visit and were routinely monitored at the examination site to ensure the testing conditions complied with American National Standards Institute standards (20,21).

Covariates

Covariates include family history of hearing loss, noise exposure, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), smoking status history, and body mass index (BMI), all of which have been identified as risk factors for hearing loss in the literature reviewed (22). Trained interviewers administrated a questionnaire at the baseline and follow-up examinations for medical history related to hearing loss, noise exposure, family history of hearing loss, lifestyle factors, and general medical history. Medical history related hearing loss included self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, and CVD (stroke, heart attack, or angina). Diabetes was defined as a hemoglobin A1c level greater than or equal to 6.5% at the time of the examination, or self-reported physician diagnosis. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg, or a self-reported physician diagnosis of hypertension and current use of antihypertensive medication. Noise exposure was assessed by a history of hunting or target shooting, occupational noise exposure, and current (within the past year) noisy job. Smoking status was categorized as a nonsmoker, past smoker, or current smoker. Height and weight were measured and BMI (kg/m2) was calculated. General medical history included a self-reported history of cancer and a history of kidney disease.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-squared tests were used for associations with categorical variables and t tests were used with continuous variables for univariate analyses.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) model with the complementary log–log (cloglog) link function was used as a proportional hazard discrete time model because of the small number of follow-up intervals in this study (23). That is, the cloglog model treats data grouped by time interval and thus is a form of interval-censored survival model. Generalized estimating equation is an extension of generalized linear models to cover repeated measures and, therefore, can handle time-varying variables. In addition, time-varying covariates were incorporated to update the ototoxic medication exposure during all three examinations. Generalized estimating equation is a population-averaged approach, thus the focus is not on individuals’ odds ratios but on the average odds ratios of the two groups. Exp (b) for cloglog models is a discrete time hazard ratio estimate in one group for a binary predictor (23). For these reasons, this model was used to evaluate the association of ototoxic medication use and the incidence and progression of hearing loss.

Ototoxic medication exposure was dichotomized into users and nonusers. For each participant, person-time was allocated based on the response to the ototoxic medication use questions at the beginning of each follow-up period. Participants were censored at the examination when hearing loss was diagnosed for the incidence analysis, or at the examination when hearing was assessed as equal to or greater than 10 dB HL above baseline for the progression analysis. The number of ototoxic medications used was a continuous variable for concomitant ototoxic medications.

Selected risk factors (family history of hearing loss, smoking, diabetes, CVD, hypertension, BMI, and noise exposure) included those associated with hearing loss in published research. To reduce the risk of confounding by indication, age- and sex-adjusted models were first run for each potential individual risk factor separately. Those that were significantly associated with the incidence or progression of hearing loss were entered into multivariate models. The associations between covariates and hearing loss were examined for possible interactions with age and sex.

Statistical significance is defined as p value of less than .05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Participants’ mean age was 65.1 (SD: 10.4) years and more than half were women at baseline. Approximately 46% of participants already had hearing loss at the baseline examination. Participants’ characteristics according to hearing loss are shown in Table 2. The most common ototoxic medication taken by older adults was NSAIDs (58.3%), followed by acetaminophen (36.5%). Among ototoxic medication users, half were taking more than one class of ototoxic medication at baseline. Older age, male sex, current noisy job, history of noise exposure, smoking, CVD, diabetes, hypertension, diuretics, and a number of ototoxic medications were associated with hearing loss.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants according to Hearing Loss

| All | Hearing loss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3,614 | No (n = 1,955) | Yes (n = 1,631)a | p Value | |

| Age, year (mean ± standard deviation) | 65.1 ± 10.4 | 60.56 ± 8.5 | 70.5 ± 9.9 | <.001 |

| Age group, year (%) | <.001 | |||

| 48–59 | 35.0 | 51.4 | 15.7 | |

| 60–69 | 29.7 | 30.9 | 28.3 | |

| 70–79 | 25.1 | 15.7 | 36.1 | |

| 80+ | 10.2 | 2.0 | 19.9 | |

| Sex (male; %) | 43.3 | 33.1 | 55.2 | <.001 |

| Current noisy job (%) | 8.3 | 10.1 | 6.3 | <.001 |

| History of noise exposure (%) | 55.1 | 50.4 | 61.3 | <.001 |

| Family history of hearing loss (%) | 38.8 | 40.2 | 37.2 | .08 |

| Smoking status (%) | .001 | |||

| Never | 45.9 | 48.2 | 43.1 | |

| Past | 39.4 | 36.3 | 42.7 | |

| Current | 14.7 | 15.2 | 14.2 | |

| Cardiovascular diseases (%) | 14.2 | 8.2 | 21.7 | <.001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 10.4 | 8.1 | 13.2 | <.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 50.2 | 45.6 | 56.0 | <.001 |

| Any ototoxic medication use (%) | 84 | 83.7 | 84.7 | .10 |

| NSAIDs | 58.3 | 59.4 | 57.0 | .157 |

| Acetaminophen | 36.5 | 37.3 | 35.6 | .227 |

| Antibiotics (IV) | 19.3 | 17.8 | 21.3 | .010 |

| Loop diuretic | 6.1 | 3.2 | 9.5 | <.001 |

| Antibiotics (oral) | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.1 | .730 |

| Chemo | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.1 | .489 |

| Quinine | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.6 | .012 |

| Concomitant ototoxic medications (%) | 50.0 | 44.4 | 52.0 | <.001 |

| Body mass index (mean ± standard deviation) | 29.6 ± 5.5 | 29.6 ± 5.6 | 29.5 ± 5.4 | .44 |

| Hearing loss (%) | 45.5 | — | — | |

Note: IV = intravenous; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PTA = pure tone average.

aIncluded severe hearing loss (PTA > 60 dB HL).

Incidence of Hearing Loss

The 10-year cumulative prevalence of incidence and progression of hearing loss in this population was previously published (14). Age (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.01 for 5 years of age 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.88, 2.16) and male sex (HR = 2.00 95% CI = 1.58, 2.54) were associated with increased risk of developing hearing loss during the 10-year follow-up. Among other covariates, smoking and BMI were significant predictors for increased risk of developing hearing loss in the age-sex-adjusted model. After adjusting for age, sex, smoking, and BMI, each additional increase in the total number of ototoxic medications (HR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.25) and taking loop diuretics (HR = 1.40 95% CI = 1.05, 1.87) were associated with an increase in the incidence of hearing loss (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hazard Ratio of Incident Hearing Loss according to Ototoxic Mediation Use

| Risk factors | Age-sex adjusted Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariate adjusteda Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of ototoxic medicationsb | 1.17 (1.08, 1.27)** | 1.15 (1.06, 1.25)* |

| NSAIDs | 1.16 (0.96, 1.41) | 1.14 (0.95, 1.38) |

| Acetaminophen | 1.06 (0.86, 1.31) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.29) |

| Loop diuretic | 1.37 (1.02, 1.84)* | 1.40 (1.05, 1.87)* |

| Antibiotics (IV) | 1.14 (0.88, 1.48) | 1.09 (0.85, 1.41) |

| Antibiotics (oral) | 1.03 (0.69, 1.54) | 1.05 (0.71, 1.56) |

| Chemo | 1.29 (0.72, 2.32) | 1.28 (0.75, 2.21) |

| Quinine | 2.08 (0.72, 5.98) | 2.04 (0.77, 5.38) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; IV = intravenous; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

aAdjusted for age, sex, smoking, and body mass index.

bEach additional increase.

*p < .05, **p < .001.

Of 1,955 participants with normal hearing, 473 (24.2%) participants died or were lost to follow-up at the last follow-up. However, there was no difference in the incidence of hearing loss when data were analyzed with all those lost to follow-up coded as having developed hearing loss versus when data were analyzed with all those lost to follow-up coded as maintaining normal hearing.

Progression of Hearing Loss

Intravenous antibiotics and quinine were not associated with the progression of hearing loss before adjusting for any other covariates. They were not included for further adjusted analysis of individual effects but were included in the analysis for a total number of ototoxic medications. Age and male sex were associated with the risk of progressive hearing loss over a 10-year period. Among other covariates, hypertension and diabetes were significant predictors for progressive hearing loss in the age-sex-adjusted model. Adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, and diabetes, each additional increase in the total number of ototoxic medications (HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.18), and taking either NSAIDs (HR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.22, 1.72) or loop diuretics (HR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.08, 1.63) was associated with risk of progression of mild-to-moderate hearing loss (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hazard Ratio of Progression of Hearing Loss according to Ototoxic Medication Use

| Risk factors | Age-sex adjusted Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariate adjusteda Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of ototoxic medicationsb | 1.08 (1.00, 1.16)* | 1.09 (1.01, 1.18)* |

| NSAIDs | 1.41 (1.22, 1.70)** | 1.45 (1.22, 1.72)** |

| Acetaminophen | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) | 1.01 (0.86, 1.19) |

| Loop diuretic | 1.34 (1.10, 1.63)* | 1.33 (1.08, 1.63)* |

| Antibiotics (oral) | 1.28 (0.96, 1.71) | 1.24 (0.92, 1.69) |

| Chemo | 1.28 (0.69, 1.53) | 1.03 (0.68, 1.55) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

aAdjusted for age, sex, diabetes, and hypertension.

bEach additional increase (continuous variable).

*p < .05, **p < .001.

Discussion

This study found that older adults who took loop diuretics have a higher incidence of hearing loss and that those who took NSAIDs or loop diuretics have a worse progression of hearing loss over 10 years compared with those who do not. The use of multiple ototoxic medications was also found to affect the incidence and severity of hearing loss among community-dwelling older adults. These findings have important implications because both loop diuretics and NSAIDs are commonly used medications among older adults.

The association between hearing loss and analgesic use, such as aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen, has also been the focus of large population-based studies. Curhan and colleagues (24) conducted a study with men aged 40–74 years from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study using self-reported professionally diagnosed hearing loss over 20 years. They excluded participants aged 75 years or older. The same authors investigated the association in women aged 31–48 years in the Nurses’ Health Study II, using self-reported hearing loss over 22 years (25). In both studies, the authors found that the risk of self-reported hearing loss in those who regularly users nonaspirin NSAIDs and acetaminophen analgesics two or more times per week was higher compared with subjects who used these medications less than two times per week, but findings for aspirin were conflicting. Lin and colleagues (26) investigated further for the association between duration of analgesic use and the risk of hearing loss using data from women participants of the Nurses’ Health Study I over 22 years. Longer duration (> 6 years vs. < 1 year) of nonaspirin NSAIDs and acetaminophen use were associated with a higher risk of self-reported hearing loss.

We included aspirin in NSAIDs category and it was not associated with risk of developing hearing loss over 10 years; however, its effect on hearing was controversial in other studies (26–28). Also, our study did not find that acetaminophen was associated with the risk of incidence or progression of hearing loss.

In contrast to the findings from this study, the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study reported that people who were using salicylates, loop diuretics, and quinine at the time of the study did not have higher odds of having hearing loss (29). Similarly, the Framingham Heart Study reported that participants were taking ototoxic medications and found no significant association between ototoxic medication use and hearing loss (30). However, they did not describe in the article in which classes of medication were included as ototoxic medication. Using self-reported hearing loss, Lin and colleagues (31) also found no significant association between loop diuretic use and risk of hearing loss among women with history of hypertension in the Nurses’ Health Study I. However, hypertension itself was considered as a risk factor of hearing loss in that study and others (31,32). We adjusted for hypertension and still had significant association between loop diuretics and progression of hearing loss.

The fact that our study included more older people might be one reason for the differences since aging is a key risk factor for age-related hearing loss. In addition, the assessment of ototoxic medication use in this study involved actually identifying and confirming the medications used and was not just based on self-report. Furthermore, hearing loss was measured by pure tone audiometric tests in our study, compared with self-reported hearing loss in the studies of Curhan and colleagues (24,25) and Lin and colleagues (26,31).

The main manifestations of the pathology of age-related hearing loss in the aging cochlea are the loss of hair cells and spiral ganglion cells, and the degeneration of the lateral wall including stria vascularis (33–35). These different mechanisms may help explain why the use of multiple ototoxic medications added significantly to developing or progressing hearing loss in our study because each class of ototoxic medication may impair auditory function in a unique way. Curhan and colleagues (24) also found similar results with concomitant use of more than one class of aspirin, acetaminophen, or NSAIDs. In addition to hearing loss, the use of multiple medications increases the risk of adverse drug reactions that contribute to morbidity and mortality in older adults (36).

Our study did not find any effects from the use of antibiotics, quinine, and chemo agents on the risk of hearing loss. However, this may be due to the low proportion of people using these medications (5%, 1.1%, and 1.9%, respectively) or the fact that they were used for a very short period of time.

Participants who were taking loop diuretics had 40% higher risk of developing hearing loss and 33% higher risk of progressive hearing loss over a 10 years compared with those who did not it. Even though NSAIDs were not associated with 10-year cumulative incidence of hearing loss, participants who were taking NSAIDs had 45% greater risk of progressive hearing loss than those who did not take it. Therefore, older people who take these ototoxic medications may need to make important decisions with clinicians to stop or change the medications before their hearing is affected or to minimize the progression of hearing loss. For cases in which the medications cannot be stopped or changed, clinicians should monitor hearing at regular intervals.

The strengths of this study are that it is based on a longitudinal population-based cohort study over 10 years with large sample size and high follow-up rates throughout the study period. Data were collected using standardized protocols and methodologies for measuring medication use and hearing thresholds, and multiple measures of socioeconomic status. This study is novel because it uses objective audiometric tests to assess the long-term contribution of ototoxic drug use to age-related hearing loss among a community-based cohort.

There are some important limitations to the study. First, it is not a randomized controlled study designed to assess the association between ototoxic medication use and hearing loss, and there are limitations to what potentially confounding factors can be controlled. It is challenging to investigate the possibility of interaction of ototoxic medications and other medications that participants take. However, it would be ethically problematic to randomize individuals to these various medications used for the treatment of multiple chronic conditions. Second, the population was mostly (99%) non-Hispanic white from Beaver Dam and, thus, the results may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups. Epidemiological data suggest whites have more susceptibility genes for hearing loss than non-whites (37,38). Also, we did not have information on the exact duration (continuity of use), the dose of the ototoxic medications, drug formulations (generic vs non-generic), or the reason for taking the medication, so it was difficult to investigate duration–dose/formulations-related or indication-related ototoxicity. Finally, longitudinal studies using survivor cohorts could have underestimated new cases with hearing loss and/or lost people who died from related diseases such as CVD or diabetes that are common in the older population. Attrition and/or missing data may still be a problem in a longitudinal study using survivor cohorts despite high retention rates and nonsignificant difference with missing codes.

Conclusion

The known ototoxic medications are widely used for treating a variety of conditions, and clinicians may perceive the main effect of the drug to outweigh ototoxic side effects when they choose medications to treat certain conditions (39). However, ototoxic drug-related hearing loss in older adults could be more significant as a cause of hearing loss than in younger groups due to the high use of ototoxic drugs to treat chronic diseases, and an increased vulnerability to ototoxic drugs because of age-related impaired renal function (40). Therefore, NSAIDs and loop diuretics should be considered as potentially modifiable contributors to age-related hearing loss. Also, unnecessary polypharmacy should be minimized to avoid adverse drug reactions with careful monitoring.

Future studies in other large population-based cohorts of older adults are needed to generalize our findings to other ethnic groups. Also, the long-term consequences of duration–dosage-related ototoxicity with ototoxic drug use, especially at lower doses than commonly thought to cause ototoxicity, and the effects of the conditions for which the drug has been prescribed, have not been adequately studied. More research needs to be conducted in this field.

Funding

This work was supported by R37AG011099 (K.J.C.) from the National Institute on Aging and U10EY06594 (R.K., B.E.K.K.) from the National Eye Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgment

This work was also supported by UCSF John A. Hartford Center of Gerontological Nursing Excellence Educational Scholarship and an unrestricted grant to the UW from Research to Prevent Blindness. Partial analyses of the contribution of ototoxic medications to hearing loss were presented at the Gerontological Society of America Conference.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1. Van Eyken E, Van Camp G, Van Laer L. The complexity of age-related hearing impairment: contributing environmental and genetic factors. Audiol Neurootol. 2007;12:345–358. doi: 10.1159/000106478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bielefeld EC, Tanaka C, Chen GD, Henderson D. Age-related hearing loss: is it a preventable condition? Hear Res. 2010;264:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Age-related hearing loss 2016; https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/age-related-hearing-loss. Accessed March, 23, 2018.

- 4. Peterson M. Physical aspects of aging: is there such a thing as ‘normal’? Geriatrics. 1994;49:45–49; quiz 50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pyykko I, Toppila E, Zou J, Kentala E. Individual susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss. Audiol Med. 2007;5:41–53. doi: 10.1080/16513860601175998 [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Noise-induced hearing loss 2014; https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss. Accessed March 23, 2018.

- 7. Weinstein BE. Age-related hearing loss: how to screen for it, and when to intervene. Geriatrics. 1994;49:40–5; quiz 46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rybak LP, Ramkumar V. Ototoxicity. Kidney Int. 2007;72:931–935. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu XZ, Yan D. Ageing and hearing loss. J Pathol. 2007;211:188–197. doi: 10.1002/path.2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palomar García V, Abdulghani Martínez F, Bodet Agustí E, Andreu Mencía L, Palomar Asenjo V. Drug-induced otoxicity: current status. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:569–572. doi: 10.1080/00016480121545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Linton KL, Klein BE, Klein R. The validity of self-reported and surrogate-reported cataract and age-related macular degeneration in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1438–1446. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BE, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM, Tweed TS. Cigarette smoking and hearing loss: the epidemiology of hearing loss study. JAMA. 1998;279:1715–1719. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cruickshanks KJ, Tweed TS, Wiley TL, et al. The 5-year incidence and progression of hearing loss: the epidemiology of hearing loss study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1041–1046. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.10.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cruickshanks KJ, Nondahl DM, Tweed TS, et al. Education, occupation, noise exposure history and the 10-yr cumulative incidence of hearing impairment in older adults. Hear Res. 2010;264:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, Cruickshanks KJ, Gangnon RE. Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 15-year period: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klein BEK, Klein R.. Beaver Dam Eye Study III: Manual of Operations. Springfield, VA: U.S. Department of Commerce; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Speech-Languag-Hearing Association. Guidelines for manual pure-tone threshold audiometry. ASHA. 1987;20:297–301. doi: 10.1044/policy.GL2005-00014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American National Standard Institute. Specifications for Audiometers (ANSI S3.6-1996). New York, NY: American National Standard Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19. American National Standard Institute. American National Standard Specification for Audiometers (ANSI S3.6-2004). New York, NY: American National Standard Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20. American National Standard Institute. Maximum Permissible Ambient Noise Levels for Audiometric Test Rooms (ANSI S3.1-1991). New York, NY: American National Standard Institute; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21. American National Standard Institute. Maximum Permissible Ambient Noise Levels for Audiometric Test Rooms (ANSI S3.1-1999). New York, NY: American National Standard Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Joo Y, Hong O, Wallhagen M. The risk factor for age-related hearing loss: an intergrative review. Ann Gerontol Geriatric Res. 2016;3(2):1039–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garson GD. Generalized Linear Models/Generalized Estimating Equations. Asheboro, NC: Statistical Associates Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curhan SG, Eavey R, Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC. Analgesic use and the risk of hearing loss in men. Am J Med. 2010;123:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Curhan SG, Shargorodsky J, Eavey R, Curhan GC. Analgesic use and the risk of hearing loss in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:544–554. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin BM, Curhan SG, Wang M, Eavey R, Stankovic KM, Curhan GC. Duration of analgesic use and risk of hearing loss in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:40–47. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen Y, Huang WG, Zha DJ, et al. Aspirin attenuates gentamicin ototoxicity: from the laboratory to the clinic. Hear Res. 2007;226:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jung TT, Rhee CK, Lee CS, Park YS, Choi DC. Ototoxicity of salicylate, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and quinine. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1993;26:791–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Helzner EP, Cauley JA, Pratt SR, et al. Race and sex differences in age-related hearing loss: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2119–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moscicki EK, Elkins EF, Baum HM, McNamara PM. Hearing loss in the elderly: an epidemiologic study of the Framingham Heart Study Cohort. Ear Hear. 1985;6(4):184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin BM, Curhan SG, Wang M, Eavey R, Stankovic KM, Curhan GC. Hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of hearing loss. Am J Med. 2016;129:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gates GA, Cobb JL, D’Agostino RB, Wolf PA. The relation of hearing in the elderly to the presence of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:156–161. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880140038006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin FR, Chien WW, Li L, Clarrett DM, Niparko JK, Francis HW. Cochlear implantation in older adults. Medicine (Baltim). 2012;91:229–241. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31826b145a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dubno JR, Eckert MA, Lee FS, Matthews LJ, Schmiedt RA. Classifying human audiometric phenotypes of age-related hearing loss from animal models. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2013;14:687–701. doi: 10.1007/s10162-013-0396-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pickles JO. An Introduction to the Physiology of Hearing. 3rd ed. Bingley, UK: Emerald; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lavan AH, Gallagher P. Predicting risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2016;7:11–22. doi: 10.1177/2042098615615472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bared A, Ouyang X, Angeli S, et al. Antioxidant enzymes, presbycusis, and ethnic variability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pratt SR, Kuller L, Talbott EO, McHugh-Pemu K, Buhari AM, Xu X. Prevalence of hearing loss in black and white elders: results of the cardiovascular health study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52:973–989. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. ; COPD Clinical Research Network Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Howarth A, Shone GR. Ageing and the auditory system. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:166–171. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.039388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]