Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms and hearing loss (HL) are independently associated with increased risk of incident disability; whether the increased risk is additive is unclear.

Methods

Cox Proportional Hazards models were used to assess joint associations of HL (normal, mild, moderate/severe) and late-life depressive symptoms (defined by a score of ≥8 on the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale) with onset of mobility disability (a lot of difficulty or inability to walk ¼ mile and/or climb 10 steps) and any disability in activities of daily living (ADL), among 2,196 participants of the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study, a cohort of well-functioning older adults aged 70–79 years. Models were adjusted for age, race, sex, education, diabetes, hypertension, and body mass index.

Results

Relative to participants with normal hearing and without depressive symptoms, participants without depressive symptoms who had mild or moderate/severe HL had increased risk of incident mobility and ADL disability (hazard ratio [HR] for mobility disability, mild HL:1.34, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.09, 1.64 and HR for mobility disability, moderate/severe HL: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.75 and HR for ADL disability, mild HL: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.63, and HR for ADL disability, moderate/severe HL: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.82). Among participants with depressive symptoms, mild HL (HR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.09, 2.70) was associated with increased risk of incident mobility disability.

Conclusions

Independent of depressive symptoms, risk of incident disability was greater in older adults with HL, regardless of severity. Further research into HL interventions may delay disability onset.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Depressive symptoms, ADL disability, Mobility disability

Disability in older adults is a major public health concern in the United States. About 15.7 million Americans aged 65 years and older have at least one disability (1). Mobility disability, severe difficulty or inability to walk ¼ mile or climb one flight of stairs, is the most common disability reported among older adults (1). Disability in activities of daily living (ADL), which include eating, bathing, getting dressed, toileting, and transferring, is often seen as more debilitating disability than mobility disability. ADL disability becomes more prevalent as age increases, especially after age 85 (2,3).

Risk factors for mobility and ADL disability include hearing loss (HL) and presence of depressive symptoms. HL is common among older adults in that nearly two-thirds of adults aged 70 years and older in the United States are affected by HL(4), and HL is independently associated with depression, poorer physical functioning (5–7), and greater disability (5–7). Depressive symptoms are also prevalent among older adults, with approximately 15% of community-dwelling older adults having clinically significant depressive symptoms (8). Older adults with depression report more physical disability over time than nondepressed older adults possibly due to reduced motivation and help-seeking behavior (9) or through dysregulation in neurological and immunological function (10). Although HL and presence of depressive symptoms are independent risk factors for functional limitation and disability, understanding if experiencing these two common comorbidities jointly impacts risk of disability above and beyond having one or the other can inform prevention and intervention strategies for improving functional outcomes in older adults.

The primary aim of this study was to quantify the combined association of HL and depressive symptoms with incident mobility and ADL disability using data from participants in the Health, Aging and Body Composition (Health ABC) study. We hypothesized that the joint association of HL and depressive symptoms with incident mobility and ADL disability would be greater than HL and depressive symptoms separately.

Methods

Characteristics of the Study Sample

Participants were from the Health ABC Study, a prospective cohort study designed to evaluate age-related changes in physical function and body composition in older black and white adults. Enrollment procedures are described elsewhere (11,12). Briefly, 3,075 nonmobility-limited and nondisabled older black and white adults were recruited from field centers in Pittsburgh, PA and Memphis, TN between 1997 and 1998. All participants signed a written informed consent, and this study was approved by the institutional review boards of the study sites.

In Year 5 (2001–2002), audiometric testing was administered to 2,206 participants (13). Audiometric testing at Year 5 is a good approximation of hearing status at study initiation, since the progression of HL is slow (14). Of these 2,206 participants, 2,196 participants had complete data from the 10-item Center of Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (mCES-D) at study initiation (Year 1). These participants who also did not have prevalent mobility and/or ADL disability comprise the analytic cohort. Not all participants underwent audiometric testing at Year 5, since participants could have been censored, due to various reasons, including loss to follow up, death, or missed study visit. In this analysis, Year 1 is considered to be baseline.

Hearing Loss

Pure-tone air conduction thresholds were obtained in each ear from 0.25 to 8 kHz with headphone (TDH 39; Telephonics Corporation) using an audiometer (MA40; Maico Diagnostics) calibrated to American National Standards Institute standards (S3.6-1996). A pure-tone average (PTA) was calculated using audiometric thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in the better-hearing ear in accordance with World Health Organization guidelines. Cutpoints for HL) were defined as normal: ≤25 dB HL; mild: 26–40 dB HL; moderate: 41–70 dB HL; severe: >70 dB HL. We combined moderate and severe HL, because few had severe HL (n = 17).

Baseline Depressive Symptoms

Baseline depressive symptoms were defined by the 10-item mCES-D at study initiation (15). The mCES-D is a short self-reported measure of depressive symptoms experienced during the previous week (16). Questions cover topics of mood (five items), irritability (one item), calories (energy) (two items), concentration (one item), and sleep (one item). Items are coded on a scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time), for a maximum of 30 points. Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms. We defined baseline depressive symptoms as baseline mCES-D ≥8 (16).

Incident Mobility and ADL Disability

We examined time to (i) incident mobility disability and (ii) any incident ADL disability. Incident mobility disability was defined as two consecutive reports of having a lot of difficulty or inability to walk ¼ mile and/or climb 10 steps (17). Difficulty walking ¼ mile and climbing 10 steps were ascertained semiannually in the study from 1997 to 2011. Incident ADL disability was defined as the first report of any difficulty performing ADL (ie, bathing or showering, dressing, and transferring from bed to chair). Difficulty performing ADL was ascertained annually from 1998 to 2002, and semiannually from 2002 to 2011. Final determination of disability status was made, based on interviews with participants, hospital records, and/or proxy interviews (17).

Adjustment Covariates

Covariates included in the analysis were age, sex, race (black vs white), postsecondary education (attained vs not), history of diabetes and hypertension, body mass index (BMI), and self-reported hearing aid use at baseline. Age and BMI were mean-centered. History of diabetes was ascertained by self-reported diagnosis of diabetes, use of diabetes drugs, or fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL at baseline. History of hypertension was ascertained by having systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg, or by self-report of diagnosis of hypertension with or without antihypertensive medication use. BMI was defined as objectively measured weight in kilograms divided by height meters squared.

Statistical Analysis

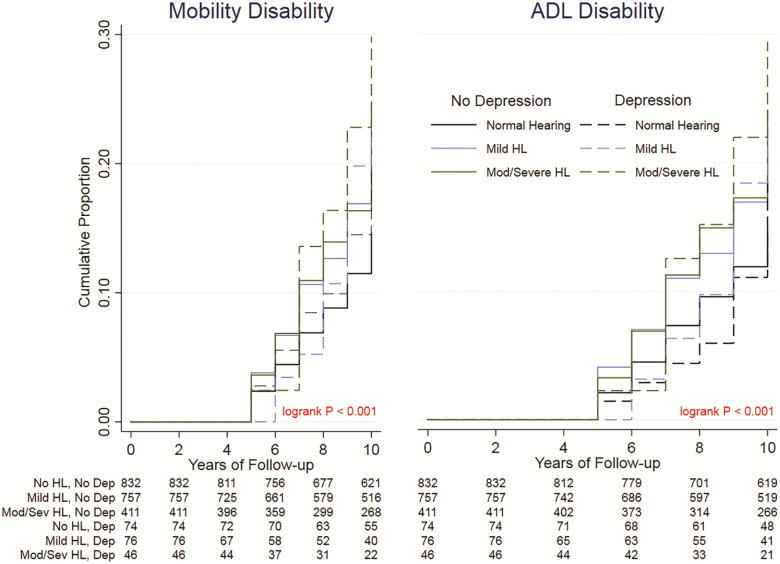

We evaluated differences in baseline covariates among those with mild, moderate/severe, and no HL, using analysis of variance for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We compared the differences in baseline covariates between those included versus excluded from the study. We also examined the cross-sectional relationship between hearing and depressive symptoms 4 years after baseline to determine if there were any associations between the two variables, by using multivariable log-linear regression models. Kaplan–Meier survival curves (18) were used to show unadjusted differences in the proportions of disability by depressive symptoms within each hearing group.

We applied Cox Proportional Hazards models (19) with Breslow ties to estimate the cause-specific hazards and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of mild and/or moderate/severe HL, with and without depressive symptoms, with both disability outcomes. The proportional hazards assumptions for the Cox models were confirmed formally by Shoenfeld’s tests and graphically by comparing Nelson–Aalen plots. The time scale was years since baseline, which was the first year of study.

We chose to model the outcomes of mobility and ADL disability separately. Mobility disability represents earlier stages of the disablement process, whereas ADL disability represents later stages of the disablement process (20). There were 849 participants with both mobility disability and ADL disability. Everyone with the ADL disability outcome had mobility disability, and most of those with mobility disability eventually developed ADL disability. The analyses differed in that the onset of ADL disability occurred later than mobility disability.

For our primary analysis, we evaluated joint effects of HL (moderate/severe and mild HL vs normal hearing) and depressive symptoms as well as the heterogeneity of effects between HL and depressive symptoms on multiplicative scale. When we examined joint effects, we used the following categories: (i) normal hearing and no depressive symptoms (reference group), (ii) mild HL and no depressive symptoms, (iii) moderate/severe HL and no depressive symptoms, (iv) normal hearing and depressive symptoms, (v) mild HL and depressive symptoms, and (vi) moderate/severe HL and depressive symptoms. In a secondary, complementary analysis, we included interaction terms between HL and depressive symptoms as well as PTA per 10 dB HL and depressive symptoms to test whether HL modified the associations of depressive symptoms with time to incident mobility and ADL disability. Stata 15.0(21) was used for the analyses.

Sensitivity Analyses

We repeated the analyses evaluating the joint effects of HL and depressive symptoms at Year 5 on incident major disability and any incident disability to see if inferences changed.

Results

Study Participants

Table 1 shows the results for the overall sample from the Health ABC Study, stratified by hearing status measured at Year 5 four years from baseline. Those with normal hearing were younger and more likely to be women, and black, than those with mild or moderate/severe HL (Table 1). Also, those with normal hearing were less likely to use hearing aids and more likely to have the lowest PTA than those with mild or moderate/severe HL (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the crude Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing the risk of incident mobility and ADL disability, respectively, among the hearing groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample From Health ABC Study (N = 2,196)

| Sample characteristics | Normal hearing | Mild hearing loss | Moderate/severe hearing loss | p Value for the difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 906 | N = 833 | N = 457 | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 73.3 (2.7) | 74.2 (2.8) | 74.9 (2.9) | <.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 558 (61.6) | 423 (50.8) | 163 (35.7) | <.001 |

| African American, n (%) | 420 (46.4) | 279 (33.5) | 118 (25.8) | <.001 |

| Postsecondary education, n (%) | 417 (46.0) | 381 (45.7) | 190 (41.6) | .249 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.4 (4.9) | 27.4 (4.8) | 27.1 (4.1) | .414 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 142 (15.7) | 144 (17.3) | 92 (20.1) | .208 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 575 (63.5) | 511 (61.3) | 279 (61.1) | .541 |

| mCES-D≥8, n (%) | 74 (8.2) | 76 (9.1) | 46 (10.1) | .494 |

| Antidepressant use, n (%) | 13 (1.4) | 19 (2.3) | 20 (4.4) | .005 |

| Hearing aid use, n (%) | 6 (0.7) | 43 (5.2) | 149 (32.4) | <.001 |

| PTA, mean (SD) | 18.2 (5.0) | 32.5 (4.3) | 50.4 (9.1) | <.001 |

Note: Diabetes is missing one observation. Hypertension is missing seven observations. Education is missing four observations. Antidepressant use is missing four observations.

BMI = Body mass index; mCES-D = 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale; PTA = Pure-tone average.

Bolded values are p < .05 from either analysis of variance for continuous variables or chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier Plot of the effects of hearing loss and depressive symptoms on incident mobility disability and ADL disability in the Health ABC Study (N = 2,196). ADL = Activities of daily living; Dep = Depressive symptoms; HL = Hearing loss; Mod/Sev = Moderate/severe hearing loss; No HL = Normal hearing.

Cross-sectional Associations between Hearing and Depressive Symptoms

Table 2 shows the association between depressive symptoms and hearing groups from multivariable log-linear regression models. After adjusting for baseline age, race, sex, education, BMI, diabetes, and hypertension, those with mild HL (prevalence ratio [PR] = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.24) or moderate/severe HL (PR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.22, 1.43) had increased likelihood of depressive symptoms than those with normal hearing.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional Association Between Hearing and Depressive Symptomsa 4 y After Baseline in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study (N = 2,196)

| Categories of hearing loss | No. with outcome/no. at risk | Risk ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal hearingb | 189/889 | REF | REF |

| Mild hearing lossc | 186/794 | 1.16 | (1.09, 1.24) |

| Moderate/severe hearing lossd | 110/443 | 1.32 | (1.22, 1.43) |

Note: All models were adjusted by age, sex, race, postsecondary education, body mass index, history of diabetes, and history of hypertension. Division of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Bolded values indicate a p < .05.

aDepressive symptoms was defined as having ≥8 on the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale. bNormal hearing was defined as pure-tone average ≤25 dB HL. cMild hearing loss was defined as pure-tone average between 26–40 dB HL. dModerate/severe hearing loss was defined as pure-tone average >40 dB HL.

Joint Associations of HL and Depressive Symptoms with Incident Mobility Disability

In the absence of depressive symptoms, HL was associated with incident mobility disability: compared with those with normal hearing and without depressive symptoms, the multivariable-adjusted HR for mild HL was 1.34, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.64, and 1.37, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.75 for moderate/severe HL (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated Joint Effects of Hearing Loss (mild and moderate/severe hearing loss vs normal hearing) and Depressive Symptoms on Onset of Incident Mobility and ADL Disability at Baseline in the Health ABC Study (N = 2,196)

| Categories of hearing loss and depressive symptomsa | Risk of incident mobility disability | Risk of incident ADL disability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. with outcome/ no. at risk | HR | 95% CI | No. with outcome/ no. at risk | HR | 95% CI | |

| Normal hearingb, No depressive symptoms | 177/832 | REF | REF | 173/832 | REF | REF |

| Mild hearing lossc, No depressive symptoms | 207/757 | 1.34 | (1.09, 1.64) | 202/757 | 1.32 | (1.08, 1.63) |

| Moderate/severe hearing lossd, No depressive symptoms | 123/411 | 1.37 | (1.08, 1.75) | 124/411 | 1.42 | (1.11, 1.82) |

| Normal hearing, Depressive symptoms | 19/74 | 1.33 | (0.82, 2.16) | 15/74 | 1.19 | (0.70, 2.02) |

| Mild hearing loss, Depressive symptoms | 21/76 | 1.71 | (1.09, 2.70) | 20/76 | 1.58 | (0.99, 2.52) |

| Moderate/severe hearing loss, Depressive symptoms | 12/46 | 1.57 | (0.87, 2.84) | 11/46 | 1.55 | (0.84, 2.87) |

| Pure-Tone Average (per 10 dB HL) and Depressive symptoms | 0.98 | (0.79, 1.23) | 1.01 | (0.79, 1.28) | ||

Note: All models were adjusted by age, sex, race, postsecondary education, body mass index, history of diabetes, and history of hypertension.

ADL = Activities of daily living; CI = Confidence interval; HR = Hazard ratio.

aDepressive symptoms was defined as having ≥8 on the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale. bNormal hearing was defined as pure-tone average ≤25 dB HL. cMild hearing loss was defined as pure-tone average between 26–40 dB HL. dModerate/severe hearing loss was defined as pure-tone average >40 dB HL.

Among participants with comorbid depressive symptoms, those with mild HL had 1.71 times the estimated risk of incident mobility disability, compared with those with normal hearing and without depressive symptoms (95% CI: 1.09, 2.70). We did not observe a significant association between moderate/severe HL with increased risk of incident mobility disability in participants with depressive symptoms (Table 3).

In a secondary analysis, we evaluated whether HL modified the association of depressive symptoms with incident mobility disability. To do this, we added an interaction term between HL and depressive symptoms. The interaction of mild HL (HR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.50, 1.87) and moderate/severe HL (HR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.40, 1.85) with depressive symptoms was significant, suggesting that HL modified the association of depressive symptoms with incident mobility disability. We also did not find any statistical evidence for an interaction between HL when treated as a continuous factor (PTA) and depressive symptoms on incident major disability (HR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.79, 1.23) (Table 3).

Joint Association of HL and Depressive Symptoms with ADL Disability

Mild HL (HR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.63) and moderate/severe HL (HR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.82) without depressive symptoms were associated with increased risk of ADL disability (Table 3). When evaluating whether HL modified the association of depressive symptoms with incident ADL disability, HL, when treated as a continuous factor (PTA), did not modify the association between depressive symptoms and incident ADL disability.

In a secondary analysis, we evaluated whether HL modified the association of depressive symptoms with ADL disability through the use of interaction terms. We found no statistical evidence of an interaction for mild HL (HR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.50, 2.02) or moderate/severe HL (HR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.41, 2.06) with depressive symptoms on incident ADL disability (data not shown). We also did not find evidence of an interaction between continuous PTA and depressive symptoms (HR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.79, 1.28).

Sensitivity Analyses

To account for any time effects from hearing assessments occurring in 4 years after baseline (Year 5), we examined the estimated joint effects of HL and depressive symptoms on mobility and ADL disability from Year 5 onward (Supplementary Table 1). When we examined onset of mobility and ADL disability 4 years from baseline and onward, we found similar results to those in the main analysis when mobility disability was the outcome. When ADL disability was the outcome, we found evidence of joint effect of HL and depressive symptoms on incident ADL disability. Individuals without depressive symptoms and with either mild HL (HR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.70) or moderate/severe HL (HR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.91) had increased risk of mobility disability, as compared with the individuals with normal hearing and without depressive symptoms, the reference group for comparisons. Those with both depressive symptoms and mild HL had 1.78 times the risk of mobility disability than the reference group (95% CI: 1.31, 2.41). As for ADL disability, mild and moderate/severe HL with and without depressive symptoms were associated with increased risk of ADL disability (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that mild and moderate/severe HL were associated with both mobility disability and ADL disability among older adults and that the risk of incident mobility disability is greater for older adults with both HL and depressive symptoms, as compared with the older adults with normal hearing and without depressive symptoms. The estimated joint effects of HL and depressive symptoms on incident mobility was observed only among those with both mild HL and depressive symptoms; the estimated joint effects of mild HL and depressive symptoms on incident ADL disability were marginally significant. These findings suggest that those with both mild HL and late-life depressive symptoms may have increased risk of mobility disability and ADL disability. Late-life depressive symptoms and HL have been shown to be independently associated with incident disability, including previous studies in this cohort (22,23). However, these studies did not examine whether HL, coupled with depressive symptoms, was associated with greater risk of disability onset. HL is associated with depression in older adults (24), which is consistent with the strong cross-sectional relationship we found between depressive symptoms and HL severity. A potential mechanism explaining the association of HL and depressive symptoms with disability onset is through cognitive load. Both HL and depressive symptoms add to cognitive load (25,26), placing a greater strain on attentional resources, which are necessary for physical mobility and functioning. The associations of both mild and moderate/severe HL with incident disability in the absence of depressive symptoms were similar, suggesting that there could be a threshold effect with the audiometric assessment.

Although the direction of the effects is positive, we found associations of HL with incident mobility disability and ADL disability in the absence of depressive symptoms, but we failed to see a similar relationship among those with depressive symptoms, in the absence of HL. When we tested for the interaction of HL and depressive symptoms directly, we found presence of an interaction between HL and depressive symptoms when mobility disability, not ADL disability, was the outcome. Yet, our sensitivity analyses show significant associations of depressive symptoms in the absence of HL with incident mobility and ADL disability when we evaluated the audiometric assessment with depressive symptoms assessed 4 years after baseline. We found positive associations between depressive symptoms in the absence of HL with incident mobility and ADL disability. The differences in the findings from the main analyses and the sensitivity analysis could be attributed to the differences in the proportion of those who reported depressive symptoms at study initiation versus 4 years after study initiation. There was a greater proportion of participants reporting depressive symptoms 4 years after study initiation than at study initiation. These findings suggest that CES-D scores, our measure for depressive symptoms, vary by year, and severity of these symptoms could persist or increase by time (27).

Similar to the differences between the results from the main analyses and sensitivity analyses when examining associations of depressive symptoms in the absence of HL with incident mobility and ADL disability, we found positive associations of moderate/severe HL and depressive symptoms with incident mobility and ADL disability when we changed the timescale to 4 years after baseline and onward in the sensitivity analyses. Moderate/severe HL and depressive symptoms contributed to an increased risk of incident mobility disability, albeit marginally significant, whereas moderate/severe HL and depressive symptoms contributed to an increased risk of incident ADL disability. With more participants having depressive symptoms 4 years after study initiation, we were more likely to detect positive joint associations of HL and depressive symptoms with incident mobility and ADL disability. Of those who had either mild or moderate/severe HL, there was a greater proportion of participants with depressive symptoms, suggesting that depressive symptoms increase with advancing age (28). Identification of both HL and depressive symptoms among older adults may help reduce the burden of disability within this population, since HL and depressive symptoms each were associated with increased risk of mobility and ADL disability as participants aged.

The main strengths of the study were repeated measures on mobility and ADL disability among older adults for up to 11 years of observation and use of an objective measure of hearing. There were several limitations to our study. First, whereas the mCES-D has high sensitivity and specificity for detecting clinically significant depressive symptoms in older adults (29), it is not a diagnostic assessment. Thus, it is possible that some participants’ depressive symptoms status may have been misclassified. Another limitation is that we used a healthier subset of the Health ABC cohort, thus limiting the generalizability of these findings. Those who were excluded were more likely to be older, African American, and have more cardiovascular risk factors and depressive symptoms as well as less than a postsecondary education than those who were included in the study (Supplementary Table 2). Lastly, HL was treated as a time-fixed predictor, even though it was collected 4 years after baseline. This approach has been used in other studies (30,31), given that HL, a chronic condition, tends to progress at a rate of 1–2 dB/year (14).

In summary, we found that older adults with both mild HL and late-life depressive symptoms were at increased risk of onset of incident mobility and ADL disability, as compared with the older adults with normal hearing and without late-life depressive symptoms. Mild and moderate/severe HL, independent of depressive symptoms, was associated with increased onset of both mobility disability and ADL disability. These findings suggest that screening for the presence of both comorbidities in health intervention programs may allow for better targeting of older adults at the greatest risk for disability. Depression screenings in older adults have been proven to be beneficial with the improvement of depressive symptoms after appropriate treatment and follow-up (32), and screening older adults for depression in primary care settings has been recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (33). As for HL, hearing aids intervention may assist with delaying further worsening disability, but more research is needed (34). Additionally, further research into the mechanistic basis of the observed associations of HL, coupled with depressive symptoms, with mobility and ADL disability onset as well as the intervening effects of long-term hearing aid use on these associations is warranted.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) Contracts N01-AG-6-2101; N01-AG-6-2103; N01-AG-6-2106; NIA grant R01-AG028050, and NINR grant R01-NR012459. This research was funded in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. J.A.D. was supported by NIH/NIA grant K01AG054693.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participants of the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study.

Conflicts of Interest

None reported.

References

- 1. He W, Larsen LJ,. U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Reports. ACS-29, Older Americans with a Disability: 2008–2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heiland EG, Welmer AK, Wang R, et al. Association of mobility limitations with incident disability among older adults: a population-based study. Age Ageing. 2016;45:812–819. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guay M, Dubois MF, Corrada M, Lapointe-Garant MP, Kawas C. Exponential increases in the prevalence of disability in the oldest old: a Canadian national survey. Gerontology. 2014;60:395–401. doi:10.1159/000358059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin FR, Thorpe R, Gordon-Salant S, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:582–590. doi:10.1093/gerona/glr002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Disability in older adults: evidence regarding significance, etiology, and risk. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:92–100. doi:10.1111/j.1532–5415.1997.tb00986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43:661–668. doi:10.1093/geront/43.5.661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen DS, Genther DJ, Betz J, Lin FR. Association between hearing impairment and self-reported difficulty in physical functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:850–856. doi:10.1111/jgs.12800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:M249–M265. doi:10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armenian HK, Pratt LA, Gallo J, Eaton WW. Psychopathology as a predictor of disability: a population-based follow-up study in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:269–275. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruce ML. Depression and disability in late life: directions for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:102–112. doi:10.1097/00019442-200105000-00003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Nevitt MC, et al. ; Health ABC Study Group Measuring higher level physical function in well-functioning older adults: expanding familiar approaches in the Health ABC study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M644–M649. doi:10.1093/gerona/56.10.M644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, et al. Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1343–1352. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.7.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin FR. Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1131–1136. doi:10.1093/gerona/glr115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wiley TL, Chappell R, Carmichael L, Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ. Changes in hearing thresholds over 10 years in older adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2008;19:281–92; quiz 371. doi:10.3766/jaaa.19.4.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carnethon MR, Biggs ML, Barzilay JI, et al. Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:802–807. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.8.802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, et al. Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA. 2006;295:2018–2026. doi:10.1001/jama.295.17.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. doi:10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cox D. Regression models and life-tables [with discussion]. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1972;34:187–202. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612- 4380-9_37 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nagi SZ. A study in the evaluation of disability and rehabilitation potential: concepts, methods, and procedures. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1964;54:1568–1579. doi:10.2105/AJPH.54.9.1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murphy RA, Hagaman AK, Reinders I, et al. ; Health ABC Study Depressive trajectories and risk of disability and mortality in older adults: longitudinal findings from the health, aging, and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:228–235. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen DS, Betz J, Yaffe K, et al. ; Health ABC study Association of hearing impairment with declines in physical functioning and the risk of disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:654–661. doi:10.1093/gerona/glu207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mener DJ, Betz J, Genther DJ, Chen D, Lin FR. Hearing loss and depression in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1627–1629. doi:10.1111/jgs.12429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ, Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:963–974. doi:10.1038/mp.2013.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin FR, Albert M. Hearing loss and dementia - who is listening?Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:671–673. doi:10.1080/13607863.2014.915924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barry LC, Allore HG, Guo Z, Bruce ML, Gill TM. Higher burden of depression among older women: the effect of onset, persistence, and mortality over time. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:172–178. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zarit SH, Femia EE, Gatz M, Johansson B. Prevalence, incidence and correlates of depression in the oldest old: the OCTO study. Aging Ment Health. 1999;3:119–128. doi:10.1080/13607869956271 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deal JA, Betz J, Yaffe K, et al. ; Health ABC Study Group Hearing impairment and incident dementia and cognitive decline in older adults: the health ABC study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:703–709. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deal JA, Sharrett AR, Albert MS, et al. Hearing impairment and cognitive decline: a pilot study conducted within the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:680–690. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. ; IMPACT Investigators. Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi:10.1001/jama.288.22.2836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Siu AL, The U. S. preventive services task force. screening for depression in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:380–387. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boothroyd A. Adult aural rehabilitation: what is it and does it work?Trends Amplif. 2007;11:63–71. doi:10.1177/1084713807301073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.