Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) during pregnancy is associated with increased respiratory morbidities and risk for chronic lung disease after preterm birth. However, the direct effects of maternal VDD on perinatal lung structure and function and whether maternal VDD increases the susceptibility of lung injury due to hyperoxia are uncertain. In the present study, we sought to determine whether maternal VDD is sufficient to impair lung structure and function and whether VDD increases the impact of hyperoxia on the developing rat lung. Four-week-old rats were fed VDD chow and housed in a room shielded from ultraviolet A/B light to achieve 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations <10 ng/ml at mating and throughout lactation. Lung structure was assessed at 2 weeks for radial alveolar count, mean linear intercept, pulmonary vessel density, and lung function (lung compliance and resistance). The effects of hyperoxia for 2 weeks after birth were assessed after exposure to fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.95. At 2 weeks, VDD offspring had decreased alveolar and vascular growth and abnormal airway reactivity and lung function. Impaired lung structure and function in VDD offspring were similar to those observed in control rats exposed to postnatal hyperoxia alone. Maternal VDD causes sustained abnormalities of distal lung growth, increases in airway hyperreactivity, and abnormal lung mechanics during infancy. These changes in VDD pups were as severe as those measured after exposure to postnatal hyperoxia alone. We speculate that antenatal disruption of vitamin D signaling increases the risk for late-childhood respiratory disease.

Keywords: vitamin D deficiency, maternal vitamin D deficiency, lung development, hyperoxia

Clinical Relevance

Increasing evidence over the past decade has shown that vitamin D deficiency (VDD) during pregnancy is associated with maternal and fetal morbidities. This high rate of pregnancy-related maternal VDD has prompted many questions concerning the physiological and clinical consequences of low serum vitamin D concentrations in both the mother and the fetus, including the long-term impact of VDD on the developing lung. We report that in addition to small airway disease, maternal VDD causes sustained alveolar and vascular abnormalities, as demonstrated by decreased lung structure and function throughout infancy. In addition, the impact of VDD on lung function was as severe as the adverse effects of postnatal hyperoxia alone, which is a more traditional model for studies of bronchopulmonary dysplasia pathogenesis, and the VDD pups were more susceptible to increased lung injury after exposure to hyperoxia after birth.

Increasing evidence over the past decade has shown that vitamin D deficiency (VDD) during pregnancy is associated with maternal and fetal morbidities, such as preeclampsia (1–4), preterm birth (5), small size for gestational age (6), and gestational diabetes (7). A recent U.S. study found that 97% of African American individuals, 81% of Hispanic individuals, and 67% of white individuals have vitamin D concentrations that are deficient (as defined by serum concentrations <20 ng/ml or <50 nmol/L) or insufficient (at concentrations of 20–32 ng/ml or >50 nmol/L and <80 nmol/L) during pregnancy (8). Pregnant and lactating women and their neonates are at especially high risk for VDD. Past studies have reported a high prevalence of cord blood VDD or insufficiency in preterm neonates, with lower vitamin D concentrations being associated with the degree of prematurity (9, 10). This high rate of pregnancy-related maternal VDD has prompted many questions concerning the physiological and clinical consequences of low serum vitamin D concentrations in both the mother and fetus, including the long-term impact of VDD on the developing lung.

Recent studies have suggested that maternal VDD has deleterious effects on fetal lung development, including findings that maternal VDD increases the risk for asthma and wheezing in childhood (11–16). In addition, low concentrations of maternal and cord blood 25(OH)D3, the major form of circulating vitamin D, have been associated with increased risk of respiratory infections in the first 3 months of life (17, 18). Preclinical studies have demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3, the hormonally active form of vitamin D, plays a role in normal lung airway development by stimulating epithelial cell maturation (19, 20), inhibiting airway smooth muscle proliferation (21), and modulating lipofibroblast proliferation and differentiation (22). In addition, VDD infant rats have decreased lung volume (15) and tracheal diameter (23). There is substantial evidence that maternal VDD negatively impacts airway development; however, whether maternal VDD may further impact distal lung structure and function, as observed in premature infants who develop the chronic lung disease of prematurity known as “bronchopulmonary dysplasia” (BPD), is uncertain.

BPD is a multifactorial disease that is characterized by sustained airway disease and abnormalities of distal lung structure, including reduced alveolar and vascular growth that persists after preterm birth (24–26). Perinatal care of neonates has improved significantly over the past two decades. As a consequence, we have seen a dramatic improvement in survival rates of extremely preterm infants; however, the incidence of BPD has increased over the past two decades (27), which likely reflects the impact of increased survival of extremely preterm infants. Recent prospective studies further suggest that antenatal determinants are strongly associated with late respiratory disease after preterm birth independent of postnatal factors that contribute to postnatal lung injury, such as hyperoxia and mechanical ventilation (28, 29). Therefore, identifying antenatal factors that contribute to susceptibility to BPD and poor respiratory outcomes in preterm infants is essential for improving long-term morbidities.

We have recently shown that vitamin D metabolism is upregulated in the normal rodent lung just before birth and that antenatal vitamin D therapy preserves lung growth and prevents pulmonary hypertension in an experimental model of BPD due to antenatal inflammation (30, 31). These findings led us to hypothesize that in addition to its impact on late airway disease, maternal VDD may cause developmental abnormalities of the distal airspace and vessels as well as sustained impairment of lung function and structure. Postnatal exposure to adverse stimuli after birth, such as hyperoxia, contributes to the pathogenesis of BPD (32).

Although oxygen therapy can be a lifesaving and necessary therapy for preterm infants, hyperoxia causes significant damage to the developing lung and leads to decreased alveolar and vascular growth (25, 32, 33). Previous studies have demonstrated that postnatal hyperoxia may amplify the negative impacts of antenatal stresses on neonatal lung growth in rodent models (34–36). Animal models of hyperoxia-mediated lung injury demonstrate pathology similar to that of BPD with alveolar simplification and decreased microvascular development (37, 38). Whether the adverse effects of maternal VDD on infant lung structure and function are comparable to the adverse effects of hyperoxia alone or whether they increase susceptibility to hyperoxia-induced lung injury has not been studied.

Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that abnormalities of proangiogenic signaling pathways, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling, play a critical role in the pathogenesis of abnormal lung vascular and alveolar development (39–41). Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a highly conserved transcription factor that enhances angiogenesis partly through upregulation of VEGF activity. HIF-1α is expressed in most cell types, is tightly regulated by O2 tension, and regulates the expression of hundreds of genes, including those critical for lung development (42). Specifically, pharmacological HIF stabilization has been demonstrated to increase the expression of VEGF, which stimulates angiogenesis (43). In addition, inhibition of HIF signaling has been shown to decrease lung VEGF expression and subsequent vascular growth in newborn rats (44). Hyperoxia-induced impairment of distal lung growth is associated with downregulation of lung VEGF and VEGF receptors (45), and treatment with recombinant VEGF therapy during or after hyperoxia exposure enhances lung growth (45). Importantly, exogenous 1,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to increase whole-lung VEGF and VEGFR2 protein concentrations in vivo (46) and in cultured human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells (47). We have previously found that 1,25(OH)2D3 increased survival, oxygenation, and alveolarization in an experimental model of BPD in part through increased whole-lung VEGF mRNA expression (30). However, whether maternal VDD causes abnormal fetal lung development through decreased HIF/VEGF signaling remains unknown.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to determine 1) if maternal VDD alters airway alveolar and microvascular development in the developing lung, 2) whether the adverse effects of maternal VDD on infant lung function and structure are as severe as those observed in the traditional hyperoxia model of BPD; and 3) if maternal VDD increases susceptibility to hyperoxia-induced postnatal injury. On the basis of past studies, we further hypothesized that maternal VDD may decrease lung structure through disruption of lung HIF/VEGF signaling. To study these questions, we developed a rat model of maternal VDD during pregnancy and lactation, and we examined changes in infant rat lung structure and function in normoxia and after exposure to postnatal hyperoxia in pups from VDD and vitamin D–sufficient dams.

Methods

VDD Model

The institutional animal care and use committee at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus approved all procedures and protocols detailed in this article. We obtained 4-week-old female rats from Charles River Laboratories, and the rats were maintained in room air at Denver altitude (1,600 m; barometric pressure, 630 mm Hg; inspired oxygen tension, 122 mm Hg). Rats were housed in ultraviolet (UV) light–free surroundings using UV A/B–blocking films on all light fixtures, and they were exposed to a 12 hours per day/12 hours per night cycle. UV A/B levels were verified to be <1 W/m2 with a Sper Scientific UV A/B light meter. Rats were randomized to be fed ad libitum with semipurified diets containing adequate vitamin D (1,000 IU/kg diet) or no added vitamin D (0 IU/kg diet; VDD) (D09050905I AIN-93G modified diet with 0.5% calcium, 0.4% phosphorus, and no added vitamin D3; Research Diets Inc.) (48). When the rats were 8 weeks of age, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD) concentrations were determined from blood obtained via the tail vein. If 25-OHD concentrations were <10 ng/ml, the female rats were mated with vitamin D–replete males. Pups from control and VDD dams were allowed to spontaneously deliver at term. Offspring of both sexes were studied at 2 weeks of age for somatic growth, lung function, and lung structure as detailed below.

Serum 25(OH)D and Calcium

Serum samples from experimental animals were kept frozen at −80°C until analysis. 25(OH)D concentrations were measured using an ELISA kit (KAP1971 25OH Total ELISA kit; DIAsource ImmunoAssays).

Hyperoxia Exposure

At birth, pups were randomly assigned to the postnatal hyperoxia group. Newborn pups and their foster mothers were placed into hyperoxia chambers. Chamber oxygen concentration was maintained at fraction of inspired oxygen 0.95 (O2 tension, 466 mm Hg at Denver’s altitude with barometric pressure 630 mm Hg, which is equivalent to a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.75–80 at sea level) for 14 postnatal days. The hyperoxia exposure for the animals was continuous with only brief interruptions for routine animal care (<10 min/d). The oxygen concentration was continuously controlled using a PROOXoxygen controller (Reming Bioinstruments). Because of poor tolerance of adult rats to severe hyperoxia, dams were rotated during 95% oxygen exposure.

Experimental Groups

Study groups included control rats with postnatal exposure to room air (CTL-RA), vitamin D–deficient rats with postnatal exposure to room air (VDD-RA), control rats with postnatal hyperoxia exposure (CTL-HX), and vitamin D–deficient pups with exposure to postnatal hyperoxia (VDD-HX). At least 8–14 animals were included for each protocol per group.

Lung Morphometrics

Animals were killed via intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) at the end of the study (Day 14). Rat lungs were prepared and fixed in situ using PBS. To flush the blood out of the pulmonary circulation, we infused PBS into the main pulmonary artery via a right ventricular cannula. To achieve lung inflation before histology, a tracheostomy was performed, and lungs were inflated and maintained under constant pressure of 20 cm H2O with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour. Previous studies conducted in our laboratory demonstrated that this pressure of 20 cm H2O provides consistent and uniform lung inflation. In addition, we have found that lungs fixed in situ have lower chest wall contributions to lower compliance than lungs that are completely removed from the thorax. A tracheal tie was used to maintain fixation pressure, and then we immersed the lungs in paraformaldehyde solution for another 24 hours after inflation preparation. We embedded the left lower segment of the lung in paraffin and cut sections with a microtome at 5-μm thickness before staining them with hematoxylin and eosin. At the time of morphometric analysis, the investigator was blinded to the study groups.

Lung Morphometric Analysis

We assessed lung alveolarization by performing radial alveolar counts (RACs) according the methods described by Emery and Mithal (49). Briefly, we identified respiratory bronchioles as bronchioles lined by epithelium in at least one part of the vessel wall. In the center of the respiratory bronchiole, a perpendicular line was drawn extending to the edge of the acinus (as defined by a connective tissue septum or the pleura), and the number of septa intersected by this line was counted. For each animal, at least 10 counts were performed from different segments of the lung. According to previously described standard methods, we measured mean linear intercept (MLI) as the intraalveolar distance (49, 50).

Pulmonary Vessel Density and Vascular Wall Thickness

Slides with 5-μm paraffin sections were stained with von Willebrand factor, a marker for endothelial cells, to assess vascular density and vascular wall thickness. We determined pulmonary vessel density (PVD) by counting von Willebrand factor–stained vessels with external diameter <50 μm per high-power field (HPF). HPFs containing large airways or vessels with diameters >50 μm were avoided. We examined ≥10 HPFs per specimen. To asses vascular wall thickness, lung section slides were stained with mouse monoclonal ACTA2 antibody (1:1,000, clone1A4; Sigma-Aldrich). We calculated medial wall thickness for ACTA2-stained vessels <50 μm in diameter located adjacent to airways. The width of the medial wall was measured in five perpendicular locations, and an average of the five measurements was calculated. We measured the external diameter in two locations; these measurements were averaged and divided by 2 to determine the average radius. The medial wall thickness was expressed as the average width of the medial wall divided by the average radius.

Lung Mechanics

Lung function was determined in 14-day-old pups by using the flexiVent system (SCIREQ) according to standard methods stated by the manufacturer. Fourteen-day-old rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with 80 mg/kg ketamine (20 mg/ml KETASET; Zoetis Inc.) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (20 mg/ml AnaSed Injection; Akorn Animal Health). The rats were attached to the mechanical ventilation system via an 18-gauge tracheal cannula. Two-thirds of the anesthetic dose was administered before tracheostomy and cannulation, and the remainder was administered when rats were placed on mechanical ventilation. Pancuronium bromide (1 mg/ml at a dose of 10 mg/kg) was administered to prevent spontaneous breathing that would interfere with measurement of lung mechanics. Baseline mechanical ventilation consisted of a tidal volume of 10 ml/kg at a frequency of 150 breaths per minute with an inspiratory/expiratory ratio of 67% at a positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O. A measurement sequence was repeated three to six times and consisted of a recruitment maneuver whereby the airway pressure was ramped to 30 cm H2O and held for 3 seconds, followed by a 3-second multifrequency forced oscillation measurement (Quick Prime-3; SCIREQ). A 2.5-Hz sine wave (SnapShot-150; SCIREQ) was then applied at positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O and tidal volume of 10 ml/kg, and the resulting pressure–volume data were fit to the single-compartment model to determine respiratory system resistance (Rrs) and respiratory system compliance (Crs). Finally, a 16-second quasistatic pressure–volume loop was recorded with a peak airway pressure of 30 cm H2O. The average Rrs and Crs values when the coefficient of determination was >0.95 are reported; if fewer than three valid measurements were recorded, then the animal was excluded from the mechanics analysis.

Airway Reactivity

Pulmonary system mechanics were measured on sedated, tracheotomized, paralyzed, and ventilated rats at baseline and then immediately after serial 3-minute nebulizations of saline vehicle or methacholine (MCh; 1.25, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 12, and 25 ng/ml), with 3-minute recovery periods allowed after each exposure to MCh, as previously described (14). After each nebulization, two recruitment maneuvers were applied, followed by six repetitions of 7-second baseline ventilation, a Snapshot-150, 5-second baseline ventilation, and a Quick Prime-3. The average Rrs and Crs values when the coefficient of determination was >0.95 are reported.

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription, and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 50 mg of frozen lung tissue from three to five lungs per treatment condition at 14 days of life using the phenol-free RNAqueous Total RNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. A deoxyribonuclease I treatment step using the TURBO DNA-Free Kit (Invitrogen) was also performed in the RNA isolation step to remove any remaining genomic DNA. After the extraction, total RNA was quantified using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cDNA was amplified using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. One microgram of total RNA was mixed with random hexamers, primer, and deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate in a total volume of 10 μl. Samples were incubated at 65°C for 5 minutes. Then, reverse transcriptase (RT) buffer, MgCl2, DTT, RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), and SuperScript III RT were added and incubated at 50°C for 50 minutes. The RT reaction was terminated by heating at 85°C for 5 minutes. One microliter of ribonuclease H (2 U) was then added to the reaction mixture, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes. Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Invitrogen) with TaqMan probes (Invitrogen) for GAPDH, VEGF, KDR (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2), HIF-1⍺, and VDR (vitamin D receptor). Samples for each gene were plated in triplicates on Applied Biosystems MicroAmp Fast Optical 96-well reaction plates (Life Technologies). PCRs were cycled on the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) for 10 minutes at 95°C (1 cycle) and for 10 seconds at 95°C and 1 minute at 60°C for 45 cycles. The comparative cycle threshold (2−ΔΔCt) method was used to calculate the relative expression of each gene of interest in each sample compared with control samples.

Western Blot Analysis

Frozen tissue (50 mg) was homogenized in 1 ml of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer using the PowerGen 500 homogenizer (Fisher Scientific). The NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (78835; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for nuclear extraction of proteins to asses HIF-1α protein expression per the manufacturer’s instructions. Total protein concentration was determined using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each sample contained 25 μg of total protein, 4× NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (NP0007; Invitrogen), 10% vol/vol DTT (P2325; Invitrogen), and radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer up to 25 μl. BenchMark Protein Ladder (10 μl, 10747012; Invitrogen), together with 25 μl of each sample, was loaded onto NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (NP0321BOX; Invitrogen) in NuPAGE 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid SDS running buffer (NP0002; Invitrogen) at 200 V for 1 hour. After being run, proteins were transferred onto Amersham Hybond P 0.45 polyvinylidene difluoride blotting membrane (10600023; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using Trans-Blot Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 25 V for 1 hour. Ponceau S stain (P7170; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to confirm adequate transfer of proteins. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in 0.5% BSA (BP1600-100; Fisher Scientific) in Tris-buffered saline with Tween, and primary antibodies for VDR (sc-13133; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), VEGF (NB100-664; Novus Biologicals), KDR (SAB4501643; Sigma-Aldrich), HIF-1α (36169S; Cell Signaling Technology), and α-tubulin (62204; Invitrogen) were added in 0.5% BSA in TBST. After overnight incubation at 4°C, either goat antimouse horseradish peroxidase conjugate (170-6516; Bio-Rad Laboratories) or goat antirabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate (170-6515; Bio-Rad Laboratories) secondary antibodies were added to 0.5% BSA in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were developed with the Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (RPN2232; GE Healthcare Life Sciences), and the ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used to acquire images.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. We performed statistical analysis with the Prism 7.0 software package (GraphPad Software). A two-way ANOVA test that used Bartlett’s test and corrected for unequal variances was employed to compare differences between the experimental groups (control, VDD, hyperoxia, VDD + hyperoxia) for data shown in Figures 1 and 2. A one-way ANOVA and Bartlett’s test was used to compare differences between individual groups for data shown in Figures 3–7. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed adjusted P value <0.05.

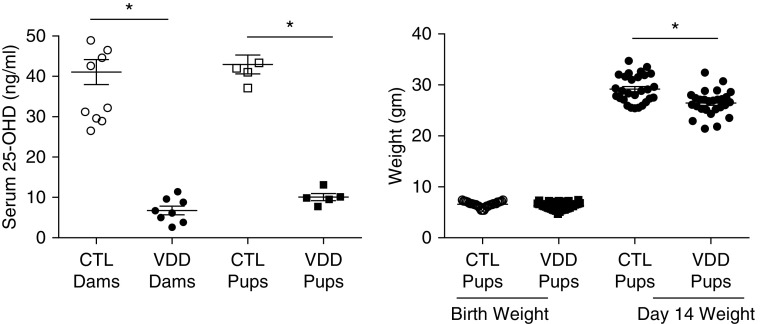

Figure 1.

Vitamin D deficiency model characteristics. Serum 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in the vitamin D deficiency (VDD) dams as compared with control dams (P < 0.01). Offspring from VDD dams had serum 25(OH)D levels significantly lower than control pups at 14 days of life (P < 0.01). Birth weights between VDD offspring and control newborn pups were not different (P = ns). At 14 days of life VDD offspring had lower body weights as compared with control pups (P < 0.01). Values are mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 9–15 animals for each group. *P < 0.0001. Error bars are 100 μm. 25-OHD = 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CTL = control; ns = not significant.

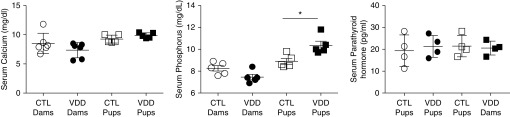

Figure 2.

Serum profile of calcium axis. Serum calcium levels in VDD dams and their offspring were not different as compared with control animals (P = ns). Serum phosphorous levels were not statistically different between VDD and control dams (P = ns). Serum phosphorous levels in VDD offspring were higher as compared with controls (P < 0.05). Serum parathyroid levels were not significantly different between VDD offspring and controls (P = ns). Values are mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 4 samples for each group. Error bars are 100 μm. *P < 0.05.

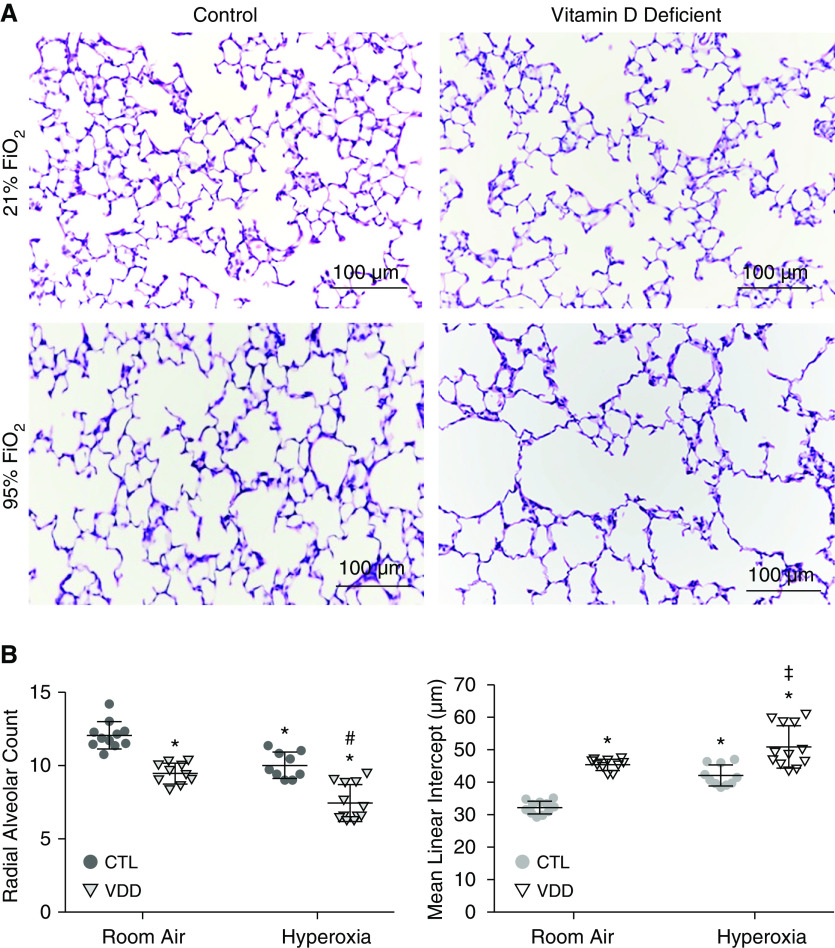

Figure 3.

Effects of maternal VDD and postnatal hyperoxia on distal lung structure at Day 14. (A) Lung histology from CTL-RA and VDD-RA are in the top panels, and CTL-HX and VDD-HX are in the bottom panels. (B) Quantification of the lung structure of vitamin D deficient offspring at Day 14. VDD-RA pups had lower RAC as compared with CTL-RA (P < 0.01). VDD-HX had decreased RAC compared with both VDD-RA and CTL-HX (P < 0.01). MLI was increased in VDD-RA offspring as compared with CTL-RA (P < 0.01), and MLI was increased in VDD-HX compared with CTL-HX and also VDD-RA (P < 0.01). Values are mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 8–12 samples for each group. *P < 0.01 versus CTL-RA, #P < 0.01 versus VDD-RA, and ‡P < 0.01 versus CTL-HX. Scale bars: 100 μm. FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; HX = postnatal hyperoxia exposure; MLI = mean linear intercept; RA = room air; RAC = radial alveolar counts.

Figure 7.

(A) Effects of maternal VDD and postnatal hyperoxia on mRNA expression of VEGF, KDR, HIF-1α, and VDR in whole lung homogenates. VEGF: VDD-RA pups had decreased VEGF mRNA as compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). CTL-HX and VDD-HX pups had decreased VEGF mRNA fold change as compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). KDR: Pups from CTL-HX and VDD-HX groups had a decrease in KDR mRNA compared with both CTL-RA and VDD-RA pups (P < 0.05). HIF-1α: VDD-RA pups had a small but nonsignificant decrease in HIF-1α mRNA expression compared with CTL-RA pups (P = ns). CTL-HX and VDD-HX pups had decreased HIF-1α mRNA compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). VDR: Pups from CTL-HX and VDD-HX groups had decreased VDR mRNA expression as compared with CTL-RA and VDD-RA pups (P < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 4 animals for each group. #P < 0.05 versus CTL and *P < 0.05 versus VDD. (B) Effects of maternal VDD and postnatal hyperoxia on protein expression of VEGF, KDR, HIF-1α, and VDR in whole lung homogenates. VEGF: VDD-RA pups did not have a change in VEGF protein expression compared with CTL-RA pups. CTL-HX and VDD-HX pups had a decrease in VEGF protein expression as compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.01 for each). KDR: Pups from CTL-HX and VDD-HX had decreased KDR expression compared to CTL-RA pups (P < 0.001 for each). As compared with VDD-RA pups, both CTL-HX and VDD-HX pups had decreased KDR expression (P < 0.05 for each). HIF-1α: VDD-RA pups had decreased HIF-1α expression as compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). In addition, VDD-HX pups also had decreased HIF-1α protein expression as compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). VDR: As compared with CTL-RA, CTL-HX and VDD-HX pups had decreased VDR expression (P < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 4 animals for each group. #P < 0.01 versus CTL. HIF-1α = hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α; KDR = vascular endothelial growth factor 2; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; VDR = vitamin D receptor.

Results

Effects of Maternal VDD on Litter Size, Birth Weight, Somatic Growth, and Vitamin D Concentration

Offspring from at least three different control and VDD dams were used for different study endpoints. From each dam, 8–15 control and VDD offspring were studied for somatic growth and lung structure and function at 2 weeks of postnatal age. Serum 25-OHD concentrations in the VDD dams before mating were reduced to 6.75 ± 1.06 ng/ml in comparison with concentrations in control dams (41.07 ± 3.11 ng/ml; P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). At 2 weeks of age, offspring from VDD dams had serum 25-OHD concentrations of 8.78 ± 0.74 ng/ml versus 45.76 ± 2.07 ng/ml in control animals (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Maternal VDD did not affect litter size (VDD, 11.1 ± 2.4 pups; control, 12.4 ± 1.7 pups; P = not significant [ns]; data not shown) or the birth weights of offspring from VDD dams (6.3 ± 0.11 g vs. 6.6 ± 0.1 g for control animals; P = ns) (Figure 1). Body weight at 2 weeks of life was decreased in VDD pups (29.18 ± 0.51 g vs. 26.45 ± 0.47 g; P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). To determine the effects of VDD on systemic calcium homeostasis, serum calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid concentrations were measured in control and VDD dams and offspring. Serum calcium concentrations were not different between VDD and control dams (7.0 ± 0.75 mg/dl vs. 9.8 ± 2.0 mg/dl; P = ns) (Figure 2). Serum calcium concentration of offspring from VDD dams was 9.88 ± 0.20 mg/dl versus 9.26 ± 0.30 mg/dl for control offspring (P = ns) (Figure 2). In addition, serum phosphorus concentrations were similar for VDD and control dams (7.46 ± 0.25 mg/dl vs. 8.25 ± 0.45 mg/dl; P = ns) (Figure 2). Serum phosphorous concentrations were 10.36 ± 0.37 mg/dl in VDD offspring versus 8.9 ± 0.26 mg/dl in control offspring at 14 days of life (P = ns) (Figure 2). Serum parathyroid concentrations were 8.23 ± 2.335 pg/ml in control pups versus 13.83 ± 2.261 pg/ml in VDD offspring (P = ns) (Figure 2). These findings demonstrate that VDD did not alter calcium and phosphorous homeostasis in rat pups.

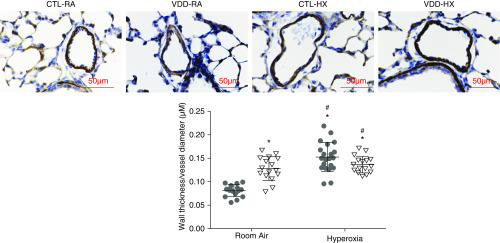

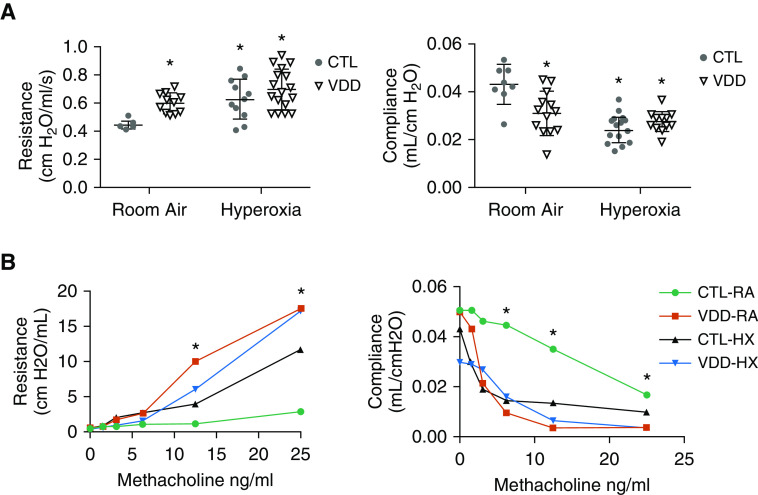

Maternal VDD Impairs Lung Structure and Function

Lung histology of both control (CTL-RA) and VDD (VDD-RA) offspring at 14 days after birth is shown in the top row of Figure 3A. Histology for the VDD-RA offspring demonstrated a simplified distal lung structure compared with CTL-RA offspring. At 14 days, RAC was decreased by 15% in VDD-RA offspring as compared with CTL-RA offspring (12 vs. 9 RAC; P < 0.05) (Figure 3B), and MLI was increased in the VDD-RA group as compared with the CTL-RA group (30 vs. 44 μm; P < 0.05) (Figure 3B). The distal lungs of VDD-RA pups had decreased PVD as compared with CTL-RA pups (17 vs. 12 vessels/HPF; P < 0.01) (Figure 4). Distal vessel wall thickness was increased in VDD-RA versus CTL-RA pups (0.08 vs. 0.12 μm; P < 0.01) (Figure 5). Total lung resistance was significantly higher in VDD-RA than in CTL-RA pups (0.44 vs. 0.60 cm H2O/ml/s; P < 0.05) (Figure 6A), and total lung compliance was lower in the VDD-RA pups than in the CTL-RA pups (0.042 vs. 0.031 ml/cm H2O; P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). Airway reactivity to MCh dosing ≥12.5 ng/ml was increased in VDD-RA pups as compared with CTL-RA pups (2.83 vs. 17.52 cm H2O/ml/s; P < 0.01) (Figure 6B). Total lung compliance in response to MCh challenge demonstrated that the VDD-RA group had significantly increased sensitivity to MCh, as characterized by decreased compliance when compared with the CTL-RA group (0.016 vs. 0.003 ml/cm H2O; P < 0.05) (Figure 6B).

Figure 4.

Distal pulmonary vessel density in lung of VDD offspring and postnatal hyperoxia. As compared with CTL-RA pups, we found decreased pulmonary vessel density (PVD) in VDD-RA pups, CTL-HX pups, and VDD-HX pups (P < 0.001 for each group). In addition, there was decreased PVD in VDD-HX pups as compared with both VDD-RA and CTL-HX pups (P < 0.001 for each). Values are mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA was used for all comparisons. n = 8–15 animals for each group. *P < 0.001 versus CTL, #P < 0.001 versus VDD-RA, and ‡P < 0.001 versus CTL-HX. HPF = High power field. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Vessel wall thickness in VDD offspring. VDD-RA pups had increased vessel wall thickness compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.01). CTL-HX pups had increased vessel wall thickness compared with CTL-RA and VDD-RA pups (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). Values are mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 8-15 animals for each group. *P < 0.01 versus CTL and #P < 05 versus VDD. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Figure 6.

(A) Effects of maternal VDD on lung function at Day 14. VDD-RA pups had increased resistance as compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). Both CTL-HX and VDD-HX pups had increased resistance compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). VDD-RA pups had decreased compliance compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). Both CTL-HX and VDD-HX pups had decreased compliance compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.05). Values are mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 10–15 animals for each group. *P < 0.05 versus CTL. (B) Effects of maternal VDD on lung function at Day 14. VDD-RA, CTL-HX, and VDD-HX pups had increased resistance in response to MCH challenge compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.01). VDD-RA, CTL-HX, and VDD-HX pups had decreased compliance in response to MCH challenge compared with CTL-RA pups (P < 0.01). Values are mean ± SEM; one-way ANOVA used for all comparisons. n = 10–15 animals for each group. *P < 0.01 versus CTL. MCh = methacholine.

Postnatal Hyperoxia Decreases Distal Lung Structure and Function

Lung histology of both CTL-RA and CTL-HX pups is shown in the left column of Figure 3A. Histology of CTL-HX animals demonstrated simplified distal lung structure as compared with that of CTL-RA animals. The CTL-HX group had decreased RAC (12 vs. 10 RAC; P < 0.05) (Figure 3B) and increased MLI (30 vs. 40 μm; P < 0.05) (Figure 2B) compared with CTL-RA animals. CTL-HX pups had decreased PVD (17 vs. 13 vessels/HPF; P < 0.05) (Figure 4) and increased vessel wall thickness (0.08 vs. 0.12; P < 0.01) (Figure 5) compared with CTL-RA pups. Postnatal hyperoxia exposure significantly increased total lung resistance (0.44 vs. 0.63 cm H2O/ml/s; P < 0.05) (Figure 6A) and decreased compliance (0.042 vs. 0.023 ml/cm H2O; P < 0.05) (Figure 6A) in control rats as compared with those exposed exclusively to room air. Airway reactivity to MCh dosing ≥12.5 ng/ml was increased in CTL-HX pups with an increase in airway resistance in response to MCh as compared with CTL-RA pups (2.83 vs. 11.68 cm H2O/ml/s; P < 0.01) (Figure 6B). Total lung compliance in response to MCh challenge demonstrated that CTL-HX pups had significantly decreased compliance in response to MCh challenge as compared with CTL-RA pups (0.016 vs. 0.0097 ml/cm H2O; P < 0.01) (Figure 6B).

Maternal VDD Increases Susceptibility to Postnatal Hyperoxia

Lung histology of both CTL-RA and VDD-HX pups is shown in Figure 3A. Histology of VDD-HX pups had simplified distal lung structure as compared with that of the VDD-RA group. Distal lungs of VDD-HX pups demonstrated reduced RAC as compared with distal lungs of the CTL-RA, VDD-RA, and CTL-HX groups (7 RAC vs. 12, 9, and 10 RAC, respectively; P < 0.05) (Figure 3B) and increased MLI (50 μm vs. 30, 44, and 40 μm, respectively; P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). The distal lungs of VDD-HX pups were found to have decreased PVD as compared with CTL-RA, VDD-RA, and CTL-HX pups (8 vessels/HPF vs. 17, 12, and 13 vessels/HPF, respectively; P < 0.01 vs. CTL-RA and P < 0.05 vs. VDD-RA and CTL-HX) (Figure 4). The distal vessels of VDD-HX pups had increased vessel wall thickness compared with those CTL-RA and VDD-RA pups (0.13 μm vs. 0.08 and 0.11 μm, respectively; P < 0.01) (Figure 5). Infant VDD-HX rats demonstrated significantly higher total lung resistance (0.70 vs. 0.44 cm H2O/ml/s; P < 0.05) (Figure 6A) and lower lung compliance than the CTL-RA animals (0.02 vs. 0.04 ml/cm H2O; P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). Airway reactivity to MCh dosing ≥12.5 ng/mg was increased in VDD-HX pups compared with CTL-RA pups at 25 ng/ml (17.1 vs. 2.83 cm H2O/ml/s; P < 0.01) (Figure 6B). Total lung compliance in response to MCh challenge demonstrated that VDD-HX pups had decreased compliance compared with CTL-RA pups (0.003 vs. 0.016 ml/cm H2O; P < 0.05) (Figure 6B).

Maternal VDD and Postnatal Hyperoxia Decrease Whole-Lung Content of VEGF, KDR, HIF-1α, and VDR

In offspring of VDD dams, we found that VEGF mRNA expression was decreased in whole lungs from VDD-RA animals at Day 14 as compared with CTL-RA animals (1.1-fold vs. 0.7-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A).We did not find significant decreases in KDR, HIF-1α, or VDR mRNA expression in VDD-RA lungs as compared with CTL-RA lungs. In whole lungs from pups exposed to postnatal hyperoxia, we found decreased VEGF mRNA (1.1-fold vs. 0.6-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A), KDR (1.1-fold vs. 0.75-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A), HIF-1⍺ (1.1-fold vs. 0.69- fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A), and VDR mRNA expression as compared with CTL-RA (1.3-fold vs. 0.55-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A). Lungs of infant VDD-HX rats demonstrated decreased VEGF mRNA expression (0.6-fold vs. 1.1-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A) as compared with CTL-RA rats. We found decreased mRNA expression of KDR (0.75-fold vs. 1.1-fold and 1.0-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A), HIF-1⍺ (0.68-fold vs. 1.1-fold and 1.0-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A), and VDR (0.55-fold vs. 1.3-fold and 1.2-fold change; P < 0.05) (Figure 7A) in whole lungs of VDD-HX rats compared with both CTL-RA and VDD-RA animals.

Offspring of maternal VDD dams did not have a change in VEGF, KDR, or VDR whole-lung protein expression compared with CTL-RA pups (Figure 7B). We did find that VDD-RA pups had decreased HIF-1α whole-lung protein expression as compared with CTL-RA pups (0.08 vs. 0.15 relative densitometry units [RDU]; P < 0.05) (Figure 7B). In the whole lungs of pups exposed to postnatal hyperoxia, we found decreased VEGF (0.56 × 106 vs. 0.84 × 106 RDU; P < 0.01) (Figure 7B), KDR (0.46 × 107 vs. 1.5 × 107 RDU; P < 0.01) (Figure 7B), and VDR protein expression (0.94 × 107 vs. 1.31 × 107 RDU; P < 0.05) (Figure 7B) as compared with CTL-RA animals. Lungs of infant VDD-HX rats had decreased VGEF (0.47 × 106 vs. 0.84 × 106 RDU; P < 0.01) (Figure 7B), KDR (0.57 × 107 vs. 1.5 × 107 RDU; P < 0.001) (Figure 7B), HIF-1α (0.07 vs. 0.15 RDU; P < 0.05) (Figure 7B), and VDR (0.80 × 107 vs. 1.31 × 107 RDU; P < 0.001) (Figure 7B).

Discussion

Recent epidemiological and preclinical studies have shown that maternal VDD during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of childhood asthma and allergy outcomes. However, the impact of maternal VDD on distal lung development and the implications for late respiratory disease in preterm infants remain understudied. In our study, we demonstrated that maternal VDD causes sustained impairment of lung growth, structure, and function during infancy, including abnormal airway function as well as decreased distal lung alveolar and vascular growth. We also observed persistent abnormalities of lung function at 2 weeks of age, as reflected by increased total Rrs and decreased Crs. We further found that adverse effects of maternal VDD on lung structure and function were as severe as the effects of postnatal hyperoxia alone, which is the traditional experimental model of BPD. In addition, VDD increased susceptibility to worse effects on lung growth than those observed with hyperoxia alone. Finally, we further report that maternal VDD causes sustained reduction of lung HIF-1α and VEGF gene and protein expression compared with control lungs.

These findings are especially interesting because of their striking implications for understanding the separate and combined adverse effects of maternal VDD and hyperoxia on lung development, which may be especially important for understanding late respiratory disease in preterm infants with the “new BPD” (25). Although previous studies have focused largely on the nature of postnatal injury, including hyperoxia exposure, for mechanistic insights into BPD, recent epidemiological data support a more modern concept that antenatal factors are likely important determinants of BPD and late respiratory disease outcomes in preterm infants (28, 29, 51). Thus, any further advances in the prevention of BPD are likely to be achieved by establishing mechanistic links between antenatal factors with disease pathogenesis and how these factors affect the respiratory outcomes after preterm birth. In trying to understand modifiable antenatal exposures, maternal VDD is a common and perhaps more correctable contributing factor to late respiratory disease than many other antenatal events, and further clinical studies that specifically address the impact of aggressive vitamin D therapy on infant outcomes after preterm birth in mothers with VDD are needed.

Clinically, preterm infants are most likely to have lower vitamin D concentrations at birth and are at the highest risk for developing late respiratory disease, especially BPD (9, 27, 52). To explore this concept, we compared the impact of maternal VDD alone with postnatal hyperoxia alone and found that the impact of VDD was at least as severe as hyperoxia, a well-established postnatal injury model for BPD. Importantly, offspring from VDD dams raised in room air have abnormal airways, as well as alveolar and vascular development at 2-week postnatal age that is similar in severity to changes in infant lung structure and function measured after 2 weeks of exposure to postnatal hyperoxia. Furthermore, in comparison with control animals, maternal VDD decreased lung VEGF mRNA as observed in rats exposed to postnatal hyperoxia alone. Overall, these findings suggest that 1) maternal VDD causes abnormal lung development across three lung compartments (airways, alveolar, and microvascular), 2) offspring from maternal VDD have a lung phenotype consistent with that of previously established animal models of BPD from hyperoxia, 3) maternal VDD increases the susceptibility of the lung to postnatal hyperoxia-induced injury, 4) abnormal lung development from maternal VDD is associated with abnormal VEGF signaling, and 5) hyperoxia-induced lung injury may be due in part secondary to decreased vitamin D signaling due to downregulation of VDR expression.

Previous animal studies have suggested that vitamin D plays a role in normal lung development (20, 53, 54) and that maternal VDD decreases tracheal diameter (23), causes distal lung simplification (14), and induces airway hyperreactivity (14) in rats at 4–8 weeks postnatal age. These findings are consistent with the association between maternal VDD and childhood asthma observed in epidemiological studies (13). Postnatal treatment of neonatal rats with vitamin D during hyperoxia has been shown to preserve lung structure, decrease extracellular matrix deposition, and inhibit inflammation (55–57). However, to our knowledge, there are no studies examining the effects of maternal VDD predisposing the newborn rat lung to postnatal injury. We have further extended past work in models of lung disease after maternal VDD with the observation that maternal VDD increases lung injury secondary to postnatal hyperoxia. This finding of increased susceptibility of newborn VDD rodent lung to postnatal hyperoxia damage is particularly important and relevant because supplemental oxygen is a known contributor to abnormal lung development in preterm infants who develop BPD (33, 58, 59) and because many preterm and term infants are born with VDD (9, 10, 60, 61). The majority of preterm infants born at <30 weeks of gestation require supplemental oxygen to treat respiratory distress syndrome during their neonatal course, which is known to impair lung growth. Our finding that VDD increases susceptibility to hyperoxia-induced reduction in lung alveolar and vascular growth has important implications regarding increased susceptibility to BPD. In addition, we further identified reduced whole-lung mRNA expression of the proangiogenic factor VEGF in the fetal lung as a potential mechanistic link between maternal VDD and abnormal fetal lung vascular development.

Previous studies of hyperoxia as a model of BPD have demonstrated enlargement of the distal airspace with a simplification of lung structure and decreased PVD (9) as well as airway hyperresponsiveness after inhalation of MCh (62). In the present study, we confirmed the impact of hyperoxia on decreased alveolar and vascular density, and we report that maternal VDD alone can cause similar severity of sustained growth arrest in the distal lung. These findings are particularly interesting because they add to the growing story of the “new BPD” and its association with antenatal risk factors of BPD independent of postnatal injury. On the basis of our present study, we further report that impaired vascular growth seen in maternal VDD may be partly due to dysregulation of VEGF signaling.

Although maternal VDD did not decrease KDR and HIF-1⍺ mRNA expression, lung KDR and HIF-1⍺ mRNA expression were decreased after postnatal hyperoxia in the CTL-HX and VDD-HX groups, suggesting that these effects were due to hyperoxia but not VDD. Maternal VDD was not associated with decreased lung VEGF or KDR protein expression. Maternal VDD decreased HIF-1⍺ protein but not mRNA expression. This discrepancy in HIF-1⍺ mRNA and protein expression may be related to methodological assessments because the protein content was specifically measured by standard approaches using nuclear extracts, whereas mRNA was determined from whole-lung homogenates. Alternatively, maternal VDD may alter lung prolyl hydroxylase expression and activity as a key regulatory mechanism. Future studies to delineate the relationship of VDD and HIF signaling represent an interesting area for investigation.

Previous work in untransformed breast cancer cells suggested that vitamin D regulates HIF-1⍺ expression through transcriptional mechanisms (63). Wang and colleagues identified a putative vitamin D response element in the HIF-1⍺ promoter and demonstrated VDR association with this site (64). Lung VEGF expression, which is a well-established downstream target of HIF-1⍺, was not different with VDD; however, these studies were performed in Day 14 rats. Whether maternal VDD alters HIF/VEGF signaling in the fetal or newborn lung is unknown, and further studies exploring temporal changes in lung gene expression are needed. It is possible that decreased VEGF expression earlier in lung development may contribute to sustained abnormalities of lung structure and function due to maternal VDD (65).

Our finding of postnatal hyperoxia decreasing HIF-1⍺ expression is consistent with current literature suggesting that HIF-1⍺ increases transcription of many genes, including VEGF, in response to decreased oxygen availability (44, 66). In addition, decreased concentrations of HIF-1⍺ have been found in the lungs of preterm baboons (67). Our finding of maternal VDD alone decreasing HIF-1⍺ expression may explain in part why the lungs of maternal VDD offspring have diminished vascular and alveolar development similar to that of lungs of infants with BPD. Because signaling occurs at the cellular level, investigating changes in molecular targets might be more evident using isolated cells, such as pulmonary endothelial cells. Future studies will be conducted to examine maternal VDD effects on HIF-1⍺/VEGF signaling at the cellular level.

Previous work has demonstrated VEGF to be critical in distal lung development and to provide protection against abnormal lug structure in the setting of neonatal lung injury (68–72). Infants with BPD have been shown to have decreased VEGF (69, 73), and pharmacological blockade of VEGF impairs postnatal lung development in infant rats (74). Intratracheal VEGF gene therapy has been shown to enhance survival and alveolarization during hyperoxia-induced lung injury in newborn rats (40). VEGF is essential for blood vessel formation (75, 76). Postnatal hyperoxia has been shown to downregulate VEGF expression in the developing lung (77–79). Although we confirmed this finding in our present study, we also demonstrated that maternal VDD alone decreased VEGF mRNA lung expression, again suggesting that maternal VDD–mediated lung injury serves as postnatal hyperoxia. We have previously demonstrated that vitamin D increases VEGF and KDR mRNA lung expression in pulmonary artery endothelial cells during endotoxin exposure (30). Our present findings may also explain why hyperoxia-induced lung injury is exacerbated in the setting of fetal VDD, and our studies contribute to the growing appreciation of the physiological consequences associated with maternal VDD.

The biological actions of the hormonally active form of vitamin D [1,25(OH)2D3] or calcitriol are mediated through the nuclear VDR (80). VDR is a ligand-dependent transcription factor, and its presence has classically been believed to be limited to kidney, bone, intestine, and parathyroid gland. Our and other laboratories have demonstrated the presence of VDR in whole lungs, pulmonary endothelial and epithelial cells of rodents (31, 81), and multiple other organ systems (81). Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of 1,25(OH)2D3 at decreasing inflammation in whole-animal studies and in cell culture (56, 82–84). We have demonstrated the lung-protective effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 in an endotoxin model of BPD (30). In addition, we have demonstrated that VDR is upregulated in late-gestation fetal rats just before birth and that intraamniotic endotoxin decreased lung VDR expression in newborn rats (31). Other investigators have also demonstrated that the inflammatory mediator TNF-α decreased VDR mRNA and protein in human bronchial smooth muscle cells and prevented the expected calcitriol increase in VDR expression (85). Interestingly, we demonstrated that postnatal hyperoxia decreased VDR mRNA and protein expression in whole lungs. These findings suggest that lung-mediated injury by inflammation and oxidative damage with hyperoxia might be imparted through altered vitamin D signaling, as evidenced by decreased VDR expression in these models.

Potential limitations of this present study include the use of only whole lung for determination of the impact of maternal VDD changes in gene and protein expression and for determination of whether postnatal vitamin D therapy for the offspring restores lung structure and function and enhances lung VEGF and HIF signaling. In addition, future work will explore the impact of maternal VDD on lung cell–specific changes in gene and protein expression, as well as postnatal vitamin D therapy of maternal VDD offspring to restore lung structure and function, and it will explore placental structure and function to determine whether placental insufficiency is a major contributing factor to prolonged respiratory disease in this model. This latter mechanism is of special interest; however, we did not find differences in body weight in control and VDD pups at birth.

In conclusion, we report that in addition to small airway disease, maternal VDD causes sustained alveolar and vascular abnormalities, as demonstrated by decreased lung structure and function throughout infancy. In addition, the impact of VDD on lung function was as severe as the adverse effects of postnatal hyperoxia alone, which is a more traditional model for studies of BPD pathogenesis, and VDD pups were more susceptible to increased lung injury after exposure to hyperoxia after birth. Our data further suggest that these sustained lung abnormalities are associated with decreased VEGF and HIF-1 expression. We speculate that recently identified prenatal and early postnatal risk factors for BPD and late childhood respiratory disease may be exacerbated by maternal VDD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Program (E.W.M.), Section of Neonatology Research Funds (E.W.M.), a K-12 Child Health Research Career Development Award (E.W.M.), and U.S. National Institutes of Health grant HL68702 (S.H.A.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: E.W.M., S.R., J.C.F., and S.H.A. Data collection: G.J.S. and T.G. Analysis and data interpretation: E.W.M., B.J.S., J.C.F., and S.H.A.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0295OC on March 5, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Simhan HN, Holick MF, Powers RW, Roberts JM. Maternal vitamin D deficiency increases the risk of preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3517–3522. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haugen M, Brantsaeter AL, Trogstad L, Alexander J, Roth C, Magnus P, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and reduced risk of preeclampsia in nulliparous women. Epidemiology. 2009;20:720–726. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a70f08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson CJ, Alanis MC, Wagner CL, Hollis BW, Johnson DD. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in early-onset severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:366, e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodham PC, Brittain JE, Baker AM, Long DL, Haeri S, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Midgestation maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1/placental growth factor ratio as predictors of severe preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2011;58:1120–1125. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner CL, Baggerly C, McDonnell S, Baggerly KA, French CB, Baggerly L, et al. Post-hoc analysis of vitamin D status and reduced risk of preterm birth in two vitamin D pregnancy cohorts compared with South Carolina March of Dimes 2009–2011 rates. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;155:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson CJ, Wagner CL, Hollis BW, Baatz JE, Johnson DD. Maternal vitamin D and fetal growth in early-onset severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:556, e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burris HH, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Litonjua AA, Huh SY, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:182, e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson DD, Wagner CL, Hulsey TC, McNeil RB, Ebeling M, Hollis BW. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is common during pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:7–12. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burris HH, Van Marter LJ, McElrath TF, Tabatabai P, Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, et al. Vitamin D status among preterm and full-term infants at birth. Pediatr Res. 2014;75:75–80. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monangi N, Slaughter JL, Dawodu A, Smith C, Akinbi HT. Vitamin D status of early preterm infants and the effects of vitamin D intake during hospital stay. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F166–F168. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-303999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litonjua AA. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for childhood allergic disease and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:179–185. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283507927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litonjua AA, Lange NE, Carey VJ, Brown S, Laranjo N, Harshfield BJ, et al. The Vitamin D Antenatal Asthma Reduction Trial (VDAART): rationale, design, and methods of a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy for the primary prevention of asthma and allergies in children. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss ST, Litonjua AA. The in utero effects of maternal vitamin D deficiency: how it results in asthma and other chronic diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1286–1287. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0160ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yurt M, Liu J, Sakurai R, Gong M, Husain SM, Siddiqui MA, et al. Vitamin D supplementation blocks pulmonary structural and functional changes in a rat model of perinatal vitamin D deficiency. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L859–L867. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00032.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zosky GR, Berry LJ, Elliot JG, James AL, Gorman S, Hart PH. Vitamin D deficiency causes deficits in lung function and alters lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1336–1343. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1596OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zosky GR, Hart PH, Whitehouse AJ, Kusel MM, Ang W, Foong RE, et al. Vitamin D deficiency at 16 to 20 weeks’ gestation is associated with impaired lung function and asthma at 6 years of age. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:571–577. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-423OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morales E, Romieu I, Guerra S, Ballester F, Rebagliato M, Vioque J, et al. INMA Project. Maternal vitamin D status in pregnancy and risk of lower respiratory tract infections, wheezing, and asthma in offspring. Epidemiology. 2012;23:64–71. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823a44d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camargo CA, Jr, Ingham T, Wickens K, Thadhani R, Silvers KM, Epton MJ, et al. New Zealand Asthma and Allergy Cohort Study Group. Cord-blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of respiratory infection, wheezing, and asthma. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e180–e187. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadeau K, Montermini L, Mandeville I, Xu M, Weiss ST, Sweezey NB, et al. Modulation of Lgl1 by steroid, retinoic acid, and vitamin D models complex transcriptional regulation during alveolarization. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:375–381. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181d23656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen TM, Guillozo H, Marin L, Tordet C, Koite S, Garabedian M. Evidence for a vitamin D paracrine system regulating maturation of developing rat lung epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L392–L399. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.3.L392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damera G, Fogle HW, Lim P, Goncharova EA, Zhao H, Banerjee A, et al. Vitamin D inhibits growth of human airway smooth muscle cells through growth factor-induced phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein and checkpoint kinase 1. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:1429–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakurai R, Shin E, Fonseca S, Sakurai T, Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, et al. 1α,25(OH)2D3 and its 3-epimer promote rat lung alveolar epithelial-mesenchymal interactions and inhibit lipofibroblast apoptosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L496–L505. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90539.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saadoon A, Ambalavanan N, Zinn K, Ashraf AP, MacEwen M, Nicola T, et al. Effect of prenatal versus postnatal vitamin d deficiency on pulmonary structure and function in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:383–392. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0482OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husain AN, Siddiqui NH, Stocker JT. Pathology of arrested acinar development in postsurfactant bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:710–717. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jobe AJ. The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:641–643. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thébaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:978–985. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1660PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1039–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrow LA, Wagner BD, Ingram DA, Poindexter BB, Schibler K, Cotten CM, et al. Antenatal determinants of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and late respiratory disease in preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:364–374. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201612-2414OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pryhuber GS, Maitre NL, Ballard RA, Cifelli D, Davis SD, Ellenberg JH, et al. Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program Investigators. Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP): study protocol of a prospective multicenter study of respiratory outcomes of preterm infants in the United States. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:37. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandell E, Seedorf G, Gien J, Abman SH. Vitamin D treatment improves survival and infant lung structure after intra-amniotic endotoxin exposure in rats: potential role for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L420–L428. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00344.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandell E, Seedorf GJ, Ryan S, Gien J, Cramer SD, Abman SH. Antenatal endotoxin disrupts lung vitamin D receptor and 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1α-hydroxylase expression in the developing rat. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309:L1018–L1026. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00253.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhandari V. Hyperoxia-derived lung damage in preterm infants. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Long term consequences of oxygen therapy in the neonatal period. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi CW, Kim BI, Hong JS, Kim EK, Kim HS, Choi JH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia in a rat model induced by intra-amniotic inflammation and postnatal hyperoxia: morphometric aspects. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:323–327. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318193f165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Normann E, Lacaze-Masmonteil T, Eaton F, Schwendimann L, Gressens P, Thébaud B. A novel mouse model of ureaplasma-induced perinatal inflammation: effects on lung and brain injury. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:430–436. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819984ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velten M, Heyob KM, Rogers LK, Welty SE. Deficits in lung alveolarization and function after systemic maternal inflammation and neonatal hyperoxia exposure. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2010;108:1347–1356. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01392.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coalson JJ, Winter V, deLemos RA. Decreased alveolarization in baboon survivors with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:640–646. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yee M, Chess PR, McGrath-Morrow SA, Wang Z, Gelein R, Zhou R, et al. Neonatal oxygen adversely affects lung function in adult mice without altering surfactant composition or activity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L641–L649. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00023.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alvira CM. Aberrant pulmonary vascular growth and remodeling in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front Med (Lausanne) 2016;3:21. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2016.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thébaud B, Ladha F, Michelakis ED, Sawicka M, Thurston G, Eaton F, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy increases survival, promotes lung angiogenesis, and prevents alveolar damage in hyperoxia-induced lung injury: evidence that angiogenesis participates in alveolarization. Circulation. 2005;112:2477–2486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng X, Wert SE, Federici R, Peters KG, Whitsett JA. VEGF enhances pulmonary vasculogenesis and disrupts lung morphogenesis in vivo. Dev Dyn. 1998;211:215–227. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199803)211:3<215::AID-AJA3>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimoda LA, Semenza GL. HIF and the lung: role of hypoxia-inducible factors in pulmonary development and disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:152–156. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201009-1393PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asikainen TM, Waleh NS, Schneider BK, Clyman RI, White CW. Enhancement of angiogenic effectors through hypoxia-inducible factor in preterm primate lung in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L588–L595. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00098.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vadivel A, Alphonse RS, Etches N, van Haaften T, Collins JJ, O’Reilly M, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors promote alveolar development and regeneration. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50:96–105. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0250OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhandari V, Elias JA. Cytokines in tolerance to hyperoxia-induced injury in the developing and adult lung. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor SK, Sakurai R, Sakurai T, Rehan VK. Inhaled vitamin d: a novel strategy to enhance neonatal lung maturation. Lung. 2016;194:931–943. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9939-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong W, Gu B, Gu Y, Groome LJ, Sun J, Wang Y. Activation of vitamin D receptor promotes VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression in endothelial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;140:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC., Jr AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooney TP, Thurlbeck WM. The radial alveolar count method of Emery and Mithal: a reappraisal 1—postnatal lung growth. Thorax. 1982;37:572–579. doi: 10.1136/thx.37.8.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Balasubramaniam V, Maxey AM, Morgan DB, Markham NE, Abman SH. Inhaled NO restores lung structure in eNOS-deficient mice recovering from neonatal hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L119–L127. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00395.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keller RL, Feng R, DeMauro SB, Ferkol T, Hardie W, Rogers EE, et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and perinatal characteristics predict 1-year respiratory outcomes in newborns born at extremely low gestational age: a prospective cohort study. J Pediatr. 2017;187:89–97, e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laughon M, Allred EN, Bose C, O’Shea TM, Van Marter LJ, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. ELGAN Study Investigators. Patterns of respiratory disease during the first 2 postnatal weeks in extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1124–1131. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marin L, Dufour ME, Nguyen TM, Tordet C, Garabedian M. Maturational changes induced by 1 α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in type II cells from fetal rat lung explants. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:L45–L52. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.265.1.L45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marin L, Dufour ME, Tordet C, Nguyen M. 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates phospholipid biosynthesis and surfactant release in fetal rat lung explants. Biol Neonate. 1990;57:257–260. doi: 10.1159/000243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao L, Shi Y, Zhao X, Hou A, Xing Y, Fu J, et al. Vitamin D attenuates hyperoxia-induced lung injury through downregulation of Toll-like receptor 4. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39:1403–1408. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Y, Li Q, Liu Y, Shu L, Wang N, Wu Y, et al. Attenuation of hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal rats by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Exp Lung Res. 2015;41:344–352. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2015.1039668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kose M, Bastug O, Sonmez MF, Per S, Ozdemir A, Kaymak E, et al. Protective effect of vitamin D against hyperoxia-induced lung injury in newborn rats. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:69–76. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Delemos RA, Coalson JJ, Gerstmann DR, Kuehl TJ, Null DM., Jr Oxygen toxicity in the premature baboon with hyaline membrane disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:677–682. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.3.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park MS, Rieger-Fackeldey E, Schanbacher BL, Cook AC, Bauer JA, Rogers LK, et al. Altered expressions of fibroblast growth factor receptors and alveolarization in neonatal mice exposed to 85% oxygen. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:652–657. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318159af61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ooms N, van Daal H, Beijers AM, Gerrits GP, Semmekrot BA, van den Ouweland JM. Time-course analysis of 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 shows markedly elevated levels in early life, particularly from vitamin D supplementation in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:647–653. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saraf R, Morton SM, Camargo CA, Jr, Grant CC. Global summary of maternal and newborn vitamin D status: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:647–668. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeda K, Okamoto M, de Langhe S, Dill E, Armstrong M, Reisdorf N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist treatment increases septation and angiogenesis and decreases airway hyperresponsiveness in a model of experimental neonatal chronic lung disease. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009;292:1045–1061. doi: 10.1002/ar.20921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang Y, Zheng W, Teegarden D. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in untransformed and Harvey-ras transfected breast epithelial cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;298:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang TT, Tavera-Mendoza LE, Laperriere D, Libby E, MacLeod NB, Nagai Y, et al. Large-scale in silico and microarray-based identification of direct 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2685–2695. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Reilly M, Thébaud B. Animal models of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: the term rat models. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L948–L958. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00160.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Asikainen TM, Ahmad A, Schneider BK, White CW. Effect of preterm birth on hypoxia-inducible factors and vascular endothelial growth factor in primate lungs. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:538–546. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abman SH. Impaired vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in the pathogenesis of neonatal pulmonary vascular disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;661:323–335. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhatt AJ, Pryhuber GS, Huyck H, Watkins RH, Metlay LA, Maniscalco WM. Disrupted pulmonary vasculature and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor, Flt-1, and TIE-2 in human infants dying with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1971–1980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2101140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brown KR, England KM, Goss KL, Snyder JM, Acarregui MJ. VEGF induces airway epithelial cell proliferation in human fetal lung in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1001–L1010. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.4.L1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kunig AM, Balasubramaniam V, Markham NE, Seedorf G, Gien J, Abman SH. Recombinant human VEGF treatment transiently increases lung edema but enhances lung structure after neonatal hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1068–L1078. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00093.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wallace B, Peisl A, Seedorf G, Nowlin T, Kim C, Bosco J, et al. Anti-sflt-1 therapy preserves lung alveolar and vascular growth in antenatal models of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:776–787. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1371OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lassus P, Turanlahti M, Heikkilä P, Andersson LC, Nupponen I, Sarnesto A, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelial growth factor and Flt-1 in fetuses, in acute and chronic lung disease, and in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1981–1987. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2012036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Le Cras TD, Markham NE, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Abman SH. Treatment of newborn rats with a VEGF receptor inhibitor causes pulmonary hypertension and abnormal lung structure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L555–L562. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00408.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS, et al. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature. 1996;380:439–442. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hosford GE, Olson DM. Effects of hyperoxia on VEGF, its receptors, and HIF-2α in the newborn rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L161–L168. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00285.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lin YJ, Markham NE, Balasubramaniam V, Tang JR, Maxey A, Kinsella JP, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide enhances distal lung growth after exposure to hyperoxia in neonatal rats. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:22–29. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000163378.94837.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maniscalco WM, Watkins RH, D’Angio CT, Ryan RM. Hyperoxic injury decreases alveolar epithelial cell expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in neonatal rabbit lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:557–567. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.5.9160838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pinette KV, Yee YK, Amegadzie BY, Nagpal S. Vitamin D receptor as a drug discovery target. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2003;3:193–204. doi: 10.2174/1389557033488204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang Y, Zhu J, DeLuca HF. Where is the vitamin D receptor? Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Foong RE, Shaw NC, Berry LJ, Hart PH, Gorman S, Zosky GR. Vitamin D deficiency causes airway hyperresponsiveness, increases airway smooth muscle mass, and reduces TGF-β expression in the lungs of female BALB/c mice. Physiol Rep. 2014;2:e00276. doi: 10.1002/phy2.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang H, Chu X, Huang Y, Li G, Wang Y, Li Y, et al. Maternal vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy results in insulin resistance in rat offspring, which is associated with inflammation and Iκbα methylation. Diabetologia. 2014;57:2165–2172. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen L, Eapen MS, Zosky GR. Vitamin D both facilitates and attenuates the cellular response to lipopolysaccharide. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45172. doi: 10.1038/srep45172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Agrawal T, Gupta GK, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D deficiency decreases the expression of VDR and prohibitin in the lungs of mice with allergic airway inflammation. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;93:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.