Abstract

Elder mistreatment is complex, with cases typically requiring integrated responses from social services, medicine, civil law, and criminal justice. Only limited research exists describing elder mistreatment prosecution and its impact. Researchers have not yet examined administrative prosecutorial data to explore mistreatment response, and no standardized analytic approach exists. We developed a rigorous, systematic methodologic approach to identify elder mistreatment cases in prosecutorial data from cases of crimes against victims aged ≥60. To do so, we operationalized elements of the accepted definition of elder mistreatment, including expectation of trust and vulnerability. We also designed an approach to categorize elder mistreatment cases, using the types of charges filed, into: financial exploitation, physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal/emotional/psychological abuse, and neglect. This standardized methodological approach to identify and categorize elder mistreatment cases in prosecution data is an important preliminary step in analyzing this potentially untapped source of useful information about mistreatment response.

Keywords: criminal justice elder abuse, elder mistreatment, methodology, prosecution

Elder mistreatment is a common phenomenon that affects 5 to 10% of community-dwelling older adults (Acierno et al., 2010; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015) and more than 20% of nursing home residents (Rosen, Pillemer, & Lachs, 2008) annually. Cases are often complex and require integrated responses from social services, medical, civil law, and criminal justice systems. In multidisciplinary efforts to address elder abuse, each system offers different resources to reduce re-victimization. The criminal justice system, which is often involved in the most severe cases and usually after other intervention approaches have failed, is intended to protect victims and the community by punishing criminal conduct and preventing it from recurring (Stiegel, 2017). Additionally, involvement of the criminal justice system may serve as a deterrent and communicate that elder abuse will not be tolerated by society (Wallace & Crabb, 2017). The scope and impact of these criminal justice interventions is poorly understood, though, and would benefit from additional research.

The Criminalization of Elder Mistreatment

For nearly two decades after elder mistreatment was initially described as a phenomenon in the early 1970s (Burston, 1975; Stannard, 1973), it was regarded primarily as a social and occasionally as a medical issue, rather than a crime (Payne, 2002). In fact, response to mistreatment was designed assuming that victims would be best served by involving the criminal justice system as little as possible (Wolf, 2008). Criminal justice professionals rarely received referrals and did not recognize the extent of the problem or view the issue as critical (Heisler & Stiegel, 2004; Heisler, 2000; Plotkin, 1988). Further, they lacked training and experience in handling cases (Heisler & Stiegel, 2004; Heisler, 2000; Plotkin, 1988).

In the early 1990s, legislators and policymakers began to believe that, particularly in serious cases, the criminal justice system could play an important role in intervening to stop abuse, protecting victims, and holding perpetrators accountable (Heisler & Stiegel, 2004; Heisler, 1991; Heisler, 2000; Payne & Gainey, 2006). New elder abuse-specific statutes were enacted, penalty/sentencing enhancements were introduced, and mandatory reporting laws were passed (Heisler & Stiegel, 2004; Heisler, 2000; Payne & Gainey, 2006). Along with this criminalization came expectations that the criminal justice system would intensify efforts to intervene and prevent elder mistreatment (Payne, Berg, & Toussaint, 2001; Wolf, 1996). Since then, educational programs have been developed for law enforcement and prosecutors (Morgan & Scott, 2003; Uekert et al., 2012). Promising practices have been identified (Heisler, 2000; Miller & Johnson, 2003), as well as goals for improvement (Heisler & Stiegel, 2004). Some police departments (Payne & Gainey, 2006; Payne et al., 2001) and prosecutorial offices (Heisler & Stiegel, 2004) have developed units to focus on elder abuse. In addition, some communities across the US have assembled multi-disciplinary teams with varied names (Breckman, Callahan, & Solomon, 2015; Navarro, Gassoumis, & Wilber, 2013) to collaboratively address challenging cases and have recognized the importance of participation of police and prosecutors on those teams. Researchers have found that the existence of such multi-disciplinary teams may have an impact on rates of prosecution of elder abuse cases (Navarro et al., 2013).

Limited Research on Criminal Justice Interventions

Despite this increasing focus, limited research exists describing prosecutorial involvement and its impact on cases of elder mistreatment, and analytic approaches have varied widely. Most commonly, small amounts of information about prosecution has been gleaned from adult protective services data (Jackson & Hafemeister, 2013b; Navarro et al., 2013), Medicaid Fraud Reports (Payne, 2010, 2013; Payne, Blowers, & Jarvis, 2012; Payne & Gainey, 2006), or from court filings (Daly, Xu, & Jogerst, 2017). Data gleaned from these sources are limited, however.

Additionally, crime against older adults has been explored using the US federal government’s criminal data collection systems: Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Uniform Crime Reports and National Incident-Based Reporting System (Krienert, Walsh, & Turner, 2009), as well as Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey. These federal data sources, however, do not include the specificity to distinguish elder abuse from other crimes against older adults and do not include all types of criminal elder mistreatment. (Liao & Mosqueda, 2006; Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015; Stiegel, 2017).

To our knowledge, researchers have not yet closely examined data gathered and maintained by prosecutorial offices pertaining to their handling of elder abuse cases. This administrative data source contains rich information about the criminal justice process, including outcomes for perpetrators and victims, which are of potential interest to policy makers, funders, and professionals in a broad range of systems. To successfully conduct criminal justice research on elder mistreatment, it is critical to have a strategy to identify and categorize cases of elder mistreatment among all crimes against older adult victims. For a future analysis of criminal justice intervention in King County, Washington, we developed a rigorous, systematic methodologic approach to identify and categorize cases of elder mistreatment. We describe this approach in detail here.

Methods

To develop our approach to identify elder mistreatment cases in prosecutorial data among crimes against older adult victims, we examined carefully the elements of the accepted definition of elder mistreatment and operationalized them for criminal justice data. We also designed an approach to categorize elder mistreatment cases, using the types of charges filed. Given that, currently, some criminal justice data is stored in electronic databases while other data in paper files, we attempted to develop a strategy that may be used regardless of the data format.

Defining elder mistreatment

The field of elder mistreatment research and practice has struggled for decades (Connolly, Brandl, & Breckman, 2014; Goergen & Beaulieu, 2013; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; Mysyuk, Westendorp, & Lindenberg, 2013; National Research Council, 2003) to agree on a definition of the phenomenon which encompasses a multitude of mistreatment behaviors and differentiates between elder mistreatment and other crimes or behaviors against older adults. No universally-accepted definition currently exists, but most include concepts of older age, relationship between the victim and abuser, and the vulnerability of the victim.

Age Threshold

Different threshold ages have been used to define older adulthood legally, socially, and medically. The most commonly used threshold in elder mistreatment is age ≥60. The Elder Justice Act (National Health Policy Forum, 2010) defines elder mistreatment using this age, and it is the age cutoff used for elder abuse laws in many jurisdictions. This is also the minimum age for eligibility for services under the Older Americans Act (National Health Policy Forum, 2012), and most state Adult Protective Services agencies, including Washington, define older adults as aged ≥60 (Government Accountability Office, 2011; Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015).

Expectation of Trust

Most definitions of elder mistreatment include the concept, also used by a 2002 National Academy of Sciences panel, that elder mistreatment involves a trusting relationship between an older person and another individual in which the trust has been violated in some way (National Research Council, 2003). Framing elder mistreatment as within a relationship which has “an expectation of trust” is intended to exclude criminal acts by strangers with no connection to the victim. Though family and caregivers are included, others may also be in a relationship with an older adult with an expectation of trust based on their professional role, even if they do not know the older adult personally (Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015), This includes: physicians and nurses, nursing home staff, attorneys, and financial services professionals (Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015). There is ongoing debate about whether those who enlist the trust of an older person to exploit them are in a relationship “with an expectation of trust.”

Vulnerability

Vulnerability of the older adult victim is also typically a component of the definition of elder mistreatment. Though US states use different criteria to establish vulnerability, in many states, Adult Protective Services’ only has authority to investigate cases where an older adult is vulnerable (Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015; Stiegel & Klem, 2007). This vulnerability may be determined by, for example, the existence of mental or physical impairments, receiving services from a community care agency, having a guardian or conservator, or living in a nursing home (Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015; Stiegel & Klem, 2007).

Current Definition

The definition that we believe best captures current understanding of the phenomenon and on which we based our analytic approach is that developed for the 2014 Elder Justice Roadmap, a report prepared by a large, multi-disciplinary team of stakeholders inside and outside the US government (National Center for Elder Abuse). This report defines elder mistreatment as: physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, as well as neglect, abandonment, and financial exploitation of an older person by another person or entity that occurs in any setting (e.g. home, community, or facility) either in a relationship where there is an expectation of trust and/or when an older person is targeted based on age or disability. Notably, this definition identifies that the victim must be an “older person” but, given variation of ages used in laws, does not specify an age. Concepts of a trust relationship between the victim and abuser (“in a relationship where there is an expectation of trust”) and vulnerability (“targeted based on age or disability”) are included. Notably, in this definition, either a trust relationship or vulnerability (but not both) is necessary to label a case as elder mistreatment.

Operationalizing the definition of elder mistreatment for criminal justice data

To operationalize this definition for criminal justice data, we incorporated the concepts of “relationship where there is an expectation of trust” and vulnerability “targeting based on age or disability” to develop an approach to identify cases of elder mistreatment from among all cases of crimes against victims aged ≥60. We recognized that a broad range of data elements within criminal justice data exist any of which, if present, would be sufficient to label a case as elder mistreatment, even in isolation. Our approach involves searches within criminal justice data (in either electronic databases or paper files) for the presence of each of these data elements. These elements include both aspects of the crimes charged and the nature of the relationship between the victim and the defendant. We believed that using all of these was important to ensure that all elder mistreatment cases are identified. Prosecutorial decisions about which charges to file may be related to issues beyond the nature of the crime, such as what may be proven in court. Additionally, in administrative criminal justice data, information about the victim and defendant is commonly missing because it is not available or not recorded.

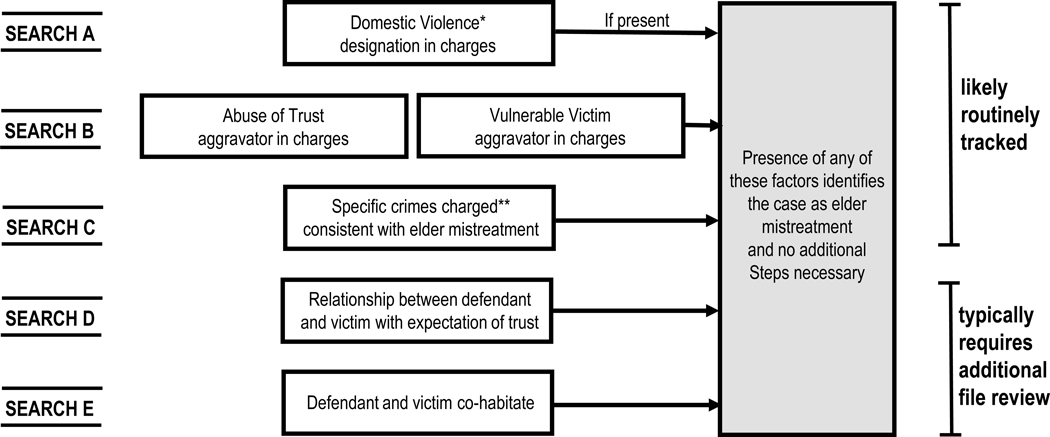

Our approach, which involves multiple searches within administrative criminal justice data for elements identifying a case as elder mistreatment, is summarized in Figure 1. We envisioned the search for the presence of each of these data elements in either electronic databases or paper files as a “step” in the process of identifying cases of elder mistreatment within criminal justice data. We intended for each search in the process of identifying cases of elder mistreatment to be independent of the others. As a result, these searches could be conducted in any order with the same total number of cases identified. Despite the fact that these independent searches for the presence of each of the relevant data elements could be conducted in any order, we believed that presenting them as a “stepwise” approach (Searches A-E) was intuitive and would allow researchers to compare the number of cases added in each search “step” in different jurisdictions or over time. Naturally, even though the total number of cases ultimately identified would be the same, if these searches were conducted in a different order, the number of additional cases identified in each search “step” would be different.

Figure 1:

Approach to identify cases of elder mistreatment from among cases of crimes against victims aged ≥60 within criminal justice data

*The definition of “domestic violence” in Washington includes any family member. This approach would be impacted in other states where the definition of domestic violence is limited to spouse / intimate partner.

**The complete text of all statutes included within our methodologic approach is available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/

In Search A, we searched for all cases that were filed with a domestic violence designation and labeled them as elder mistreatment. In Washington state law, this designation may be applied to: “All crimes against persons and property crimes involving family or household members…including spouses, former spouses, persons who have a child in common, adults related by blood or marriage, persons who have or have had a dating relationship, persons who have a biological or legal parent-child relationship, including stepparents and grandparents.” In each subsequent search “step,” we examined cases not previously categorized as elder mistreatment and added cases to this population.

In Search B, we searched for cases with an “abuse of trust” or “vulnerable victim” aggravator. In Washington, the “abuse of trust” aggravator may be added if the “defendant used his or her position of trust, confidence, or fiduciary responsibility to facilitate the commission of the current offense” (Washington State Legislature). The vulnerable victim aggravator may be added if the “defendant knew or should have known that the victim of the current offense was particularly vulnerable or incapable of resistance” (Washington State Legislature). Both of these concepts reflect the Elder Justice Roadmap definition of elder mistreatment.

In Search C, we searched remaining cases for charges that represented elder mistreatment regardless of the relationship between the defendant and the victim or other factors. Charges that were included are listed in Table 1. The complete text of all statutes included within our methodology and the manuscript are available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/ This website, maintained by the Washington State Legislature, shows the Revised Code of Washington (RCW), all of the permanent laws in force within the state. To prepare this list, the authors, including one (PBU) with more than 20 years of prosecutorial experience in King County, systematically examined all Washington state criminal statutes.

Table 1:

Criminal charges in Washington State consistent with elder mistreatment regardless of other available information

| Charge Statute | Charge Description* |

|---|---|

| RCW 9A.42.020 | Criminal mistreatment in the 1st degree |

| RCW 9A.42.030 | Criminal mistreatment in the 2nd degree |

| RCW 9A.42.035(1)(b) | Criminal mistreatment in the 3rd degree |

| RCW 9A.44.050(1)(f) | Rape in the second degree: When the victim is a frail elder or vulnerable adult and the perpetrator is a person who is not married to the victim but (i) Has a significant relationship with the victim; or (ii) Was providing transportation, within the course of his or her employment, to the victim at the time of the offense |

The complete text of all statutes is available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw

We recognized that only examining aspects of charges filed was not sufficient to identify all cases of elder mistreatment. Many crimes may be considered elder mistreatment if committed by a trusted person but not if committed by a stranger. Decisions on which charges to file may be based on what may be proven in court. Additionally, under certain circumstances, if multiple crimes are committed, a prosecutor may charge only the most serious offense. Therefore, Searches D and E were both intended to further operationalize the “relationship with an expectation of trust” element of the elder mistreatment definition.

In Search D, we examined the relationship between the defendant and the victim, to the extent it had been identified during the abstraction process. We divided types of relationships into those that we believed definitely represented elder mistreatment and those that did not necessarily. These specific relationships were combined into larger groups. The list of relationships in each of these categories is shown in Table 2. This list was developed over numerous meetings using a consensus process by the authors, many of whom have extensive legal, medical, and social expertise in elder mistreatment research and response.

Table 2:

Relationships between defendant and victim consider to definitely represent elder mistreatment vs. not necessarily elder mistreatment for use in case identification within criminal justice data

| Definitely Elder Mistreatment | Not Necessarily Elder Mistreatment |

|---|---|

| Spouse/partner | Neighbor |

| Ex-spouse/partner | Acquaintance |

| Dating relationship | Employee |

| Child-in-common | Co-worker |

| Sibling | Landlord |

| Child (including step-child/foster-child/partner’s child) | Tenant |

| Grandchild | Caretaker |

| Other Family (eg. in-law, nephew) | Contracted worker (plumber, driver, cleaning lady) |

| Friend | Patient |

| Child’s acquaintance/friend/partner | Student |

| Grandchild’s acquaintance/friend/partner | Nursing home co-resident |

| Caregiver | Stranger |

| In-home health care provider | |

| Attorney-in-fact (power of attorney) | |

| Staff of group home/adult family home | |

| Doctor/nurse/other medical professional | |

| Financial advisor/investor/banker |

We did not attempt to develop an exhaustive list of all possible relationships but rather only divided and grouped those we encountered in the King County data under study. Despite this, given the number of cases, the list is extensive and likely reasonably comprehensive. We recognize that the formal description of the relationship between the defendant and victim may not reflect the closeness of or trust in their actual relationship, a limitation of using it to determine whether a crime is elder mistreatment. For example, an older adult may have a very close relationship with a gardener who has worked on their property for decades and may have a grandchild whom they have never met. Accurately determining the closeness of the relationship in each case, however, is unrealistic as it would require extensive case file review and would be very challenging to protocolize. Also, adequate information to assess the nature of a relationship is not always gathered in the course of a case, and thus not present in many case files. Therefore, we believe that categorizing the relationships as we have, though imperfect, is an appropriate and reproducible approach for criminal justice data.

In Search E, we examined in remaining cases whether the defendant and the victim lived together in the same household at the time of the offense. We made the assumption that an expectation of trust exists between co-habitants regardless of the other details of their relationship.

Notably, when developing this approach, we tried to consider what data would typically already be routinely tracked in criminal justice data systems versus what would typically require additional file review. As noted in Figure 1, Searches A-C involve aspects of the charges filed so are likely routinely tracked. Steps D&E, which involve the relationship between the defendant and the victim and cohabitation, would typically require additional file review, as most jurisdictions do not routinely track such information.

Categorizing Types of Elder Mistreatment in Criminal Justice Data

We also developed a taxonomy of elder mistreatment for criminal justice data by sub-categorizing cases into types of elder mistreatment, allowing for additional examination and improved understanding of the different phenomena within elder mistreatment. Previous taxonomies have been described which categorize mistreatment by type of relationship, acts of commission vs. omission, and intentional vs. unintentional acts (Hudson, 1991). Payne (2002) proposed an alternate categorization for criminology, dividing cases into physical contact offenses, property offenses, and omission offenses. Policastro (2015) and colleagues suggested division into elder abuse by caregiver, domestic/family violence, and white-collar crime. Each of these may improve understanding of aspects of elder mistreatment.

Most elder mistreatment definitions and literature, however, divide the phenomenon into mutually-exclusive categories by type of harmful behavior: financial exploitation, physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal/emotional/psychological abuse, and neglect (Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; National Center for Elder Abuse; National Research Council, 2003; Rosen, Stern, Elman, & Mulcare, 2018). While some commentators include abandonment as a separate category, most consider this to be simply a severe type of neglect (Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015).

We developed a methodological approach to categorize cases that had already been designated as elder mistreatment into one or more of these 5 types of harmful behavior using the types of charges filed. We also developed sub-categories for financial exploitation and verbal/emotional/psychological abuse to reflect important differences between the types of mistreatment included in these categories. As above, decisions about the design of this categorization and sub-categorization scheme were made by the authors, including an experienced King County prosecutor (PBU). Within this scheme, a case may be included in multiple categories (and multiple sub-categories within a category) if it consists of multiple types of mistreatment.

Financial Exploitation

Financial exploitation is most commonly defined as illegal or improper use of an older adult’s money, property, or assets (Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; National Center for Elder Abuse; Rosen et al., 2018). It is among the most common types of elder mistreatment and includes a variety of criminal behaviors that differ substantially from each other. Previous commentators have highlighted how difficult it has been to develop a universally-accepted definition of financial exploitation and have debated about whether fraud or property crimes should be included (Jackson, 2015). We believed that it was appropriate to include all of those types of crime as elder mistreatment, given that either vulnerability of the victim or a trust relationship with the perpetrator was already established.

Dividing these cases, which vary widely, further into sub-categories is critical to improving understanding of different surrounding circumstances and contexts in which these financial crimes occur. Payne (2002) has suggested dividing property offenses into two categories: exploitation by primary contacts, such as family, friends and caregivers, and fraud by secondary contacts, such as more remote acquaintances. Conrad (2011) and colleagues have developed a conceptual model/taxonomy of financial exploitation to inform identification and intervention strategies, which included division into: theft and scams, financial victimization (abuse of trust with trickery, lies), financial entitlement (spending an older adult’s money on oneself), and coercion (taking advantage, pressuring). This taxonomy was not ideal for a prosecutorial data set. Many cases had elements of several of these categories, and the detailed information about intent was not typically available in the prosecution data. Instead, primarily based on the offenses described in the laws of Washington state, we classified financial exploitation into the following four categories: (1) financial crimes (including identity theft and security fraud), (2) robbery/burglary, (3) crimes commonly related to theft of assets, and (4) crimes related to theft of property. Notably, we distinguished robbery/burglary, which involves either the use of violence or entering a premises without permission from other crimes involving theft of property. These categories and sub-categories, as well as charges used to place cases in these categories, are shown in Table 3.

Table 3:

Criminal charges in Washington State consistent with types of financial exploitation among elder mistreatment cases Category/Sub-Category

| Category/Sub-Category | Definition/Description | Washington State Charges Included | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge statute | Charge Description* | ||

| Financial crimes | |||

| Identity Theft | Using someone’s personal information to commit a crime | RCW 9.35.020 (1), (2) | Identity theft in the first degree |

| RCW 9.35.020 (3) | Identity theft in the second degree | ||

| Securities fraud | Fraud related to the offer, sale or purchase of securities | RCW 21.20.010, RCW 21.20.400 | Unlawful offers, sales, purchases |

| Robbery/Burglary | |||

| Robbery | Taking property from another through the use or threatened use of force | RCW 9A.56.200 | Robbery in the 1st degree |

| RCW 9A.56.210 | Robbery in the 2nd degree | ||

| Burglary | Entering a building without permission with the intent to commit a crime therein | RCW 9A.52.020 | Burglary in the 1st degree |

| RCW 9A.52.025 | Residential Burglary | ||

| RCW 9A.52.030 | Burglary in the 2nd degree | ||

| Crimes Commonly Related to Theft of Assets | RCW 9A.56.030 | Theft in the 1st degree | |

| RCW 9A.56.040 | Theft in the 2nd degree | ||

| RCW 9A.56.050 | Theft in the 3rd degree | ||

| RCW 9A.56.060 | Unlawful issuance of checks or drafts | ||

| RCW 9A.60.020 | Forgery | ||

| RCW 9A.60.030 | Obtaining a signature by deception or duress | ||

| RCW 9A.56.320 | Financial fraud | ||

| Crimes Related to Theft of Property | RCW 9A.56.065 | Theft of a motor vehicle | |

| RCW 9A.56.068 | Possession of a stolen vehicle | ||

| RCW 9A.56.070 | Taking a motor vehicle without permission in the 1st degree | ||

| RCW 9A.56.075 | Taking a motor vehicle without permission in the 2nd degree | ||

| RCW 9A.56.140 | Possessing stolen property | ||

| RCW 9A.56.150 | Possessing stolen property in the 1st degree | ||

| RCW 9A.56.160 | Possessing stolen property in the 2nd degree | ||

| RCW 9A.56.170 | Possessing stolen property in the 3rd degree | ||

| RCW 9A.56.300 | Theft of a firearm | ||

| RCW 9A.56.310 | Possessing a stolen firearm | ||

| RCW 9A.82.050 | Trafficking in stolen property in the 1st degree | ||

| RCW 9A.82.055 | Trafficking in stolen property in the 2nd degree | ||

The complete text of all statutes is available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse is the intentional use of physical force that may result in bodily injury, physical pain, or impairment (Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; National Center for Elder Abuse; Rosen et al., 2018). Though less common, it is a type of mistreatment that more often leads to criminal charges. Charges we used to identify physical abuse are shown in Table 4. Notably, murder or manslaughter may be charged due to physical abuse, neglect, or both. Given that, we reviewed files from each case with either of these charges in greater detail to understand the surrounding circumstances and sub-categorize them appropriately.

Table 4:

Criminal charges in Washington state consistent with physical abuse among elder mistreatment cases*

| Charge statute | Charge Description** |

|---|---|

| RCW 9A.36.011(1) | Assault in the 1st degree |

| RCW 9A.36.021(1) | Assault in the 2nd degree |

| RCW 9A.36.031(1) | Assault in the 3rd degree |

| RCW 9A.36.041 | Assault in the 4th degree |

| RCW 9A.36.045 | Drive-by shooting |

| RCW 9A.36.050 | Reckless endangerment |

| RCW 9A.40.020(1)(b) | Kidnapping in the 1st degree |

| RCW 9A.40.040 | Unlawful imprisonment |

| RCW 46.61.520(1)(a) | Vehicular homicide |

| RCW 46.61.522(1) | Vehicular assault |

Murder or manslaughter (9A.32.030, 9A.32.060) may be charged due to physical abuse, neglect, or both. Given that, we reviewed files from each case with either of these charges in greater detail to understand the surrounding circumstances and sub-categorize them appropriately.

The complete text of all statutes is available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse includes any type of sexual contact with an elderly person that is non-consensual or sexual contact with an elderly person incapable of giving consent to the contact (Connolly et al., 2012; Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; National Center for Elder Abuse; Rosen et al., 2018). Charges used to identify this are shown Table 5.

Table 5:

Criminal charges in Washington State consistent with sexual abuse among elder mistreatment cases

| Charge statute | Charge Description* |

|---|---|

| RCW 9A.44.040 | Rape in the 1st degree |

| RCW 9A.44.050 | Rape in the 2nd degree |

| RCW 9A.44.060 | Rape in 3rd degree |

| RCW 9A.44.100 | Indecent liberties |

| RCW 9A.44.115 | Voyeurism |

The complete text of all statutes is available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw

Verbal/Emotional/Psychological Abuse

Verbal/emotional/psychological (the terms are often used interchangeably) abuse includes intentional infliction of anguish, pain, or distress through verbal or nonverbal acts (Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; National Center for Elder Abuse; Rosen et al., 2018). Though likely among the most common types of elder mistreatment, this type of mistreatment infrequently leads to criminal charges in our experience. Notably, we included vandalism in this category rather than in financial exploitation with other property crimes because perpetrators do not financially benefit from property destruction as he/she may through theft, and the crime is more commonly intended to have an emotional or psychological impact on the victim.

We also believed that dividing these cases into sub-categories may be useful. Conrad (2011) and colleagues previously developed a conceptual model/map separating psychological abuse into: isolation/deprivation, threats and intimidation, insensitivity and disrespect, and shaming and blaming. We divided verbal/emotional/psychological abuse into categories more consistent with behaviors, threats/intimidation/harassment, and vandalism. Charges we used to identify verbal/emotional/psychological abuse and these subcategories are shown in Table 6.

Table 6:

Criminal charges in Washington State consistent with types of verbal/emotional/psychological abuse among elder mistreatment cases

| Category/Sub-Category | Definition/Description | Washington State Charges Included | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge statute | Charge Description* | ||

| Threats/Intimidation/Harassment | Threatening, intimidating, or harassing another person | RCW 9.61.160 | Threats to bomb or injure property—Penalty |

| RCW 9.61.260 | Cyberstalking: electronic communication with the intent to harass, intimidate, torment, embarrass, etc. | ||

| RCW 9A.36.150 | Interfering with the reporting of domestic violence | ||

| RCW 9A.72.110 | Intimidating a witness | ||

| RCW 9.61.230(1),(2) | Telephone harassment | ||

| RCW 9A.36.080(1)(c) | Malicious harassment; Threatens a specific person or group of persons and places that person, or members of the specific group of persons, in reasonable fear of harm to person or property. The fear must be a fear that a reasonable person would have under all the circumstances | ||

| RCW 9A.46.020(1) | Harassment (threat to injure person or property) | ||

| Vandalism | Causing physical damage to another’s property | RCW 9A.36.080(1)(b) | Malicious harassment; Causes physical damage to or destruction of the property of the victim or another person |

| RCW 9A.48.070(1)(a) | Malicious mischief; Causes physical damage to the property of another in an amount exceeding five thousand dollars | ||

| RCW 9A.48.070(1)(b) | Malicious mischief in first degree – caused impairment of public service | ||

| RCW 9A.48.080(1)(a) | Malicious mischief in the 2nd degree; Causes physical damage to the property of another in an amount exceeding seven hundred fifty dollars | ||

| RCW 9A.48.090 | Malicious mischief in the 3rd degree | ||

The complete text of all statutes is available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw

Neglect

Neglect is defined as intentional or unintentional refusal or failure to fulfill any part of a person’s obligations or duties to provide care to an older adult, which may result in harm (Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; National Center for Elder Abuse; Rosen et al., 2018). Though common, neglect is infrequently criminally charged due in part to challenges in prosecuting these cases (Uekert et al., 2012). Charges we used to identify neglect are shown in Table 7. Notably, we considered abandonment to be a form of neglect and have included the appropriate charge to capture it.

Table 7:

Criminal charges in Washington State consistent with neglect among elder mistreatment cases*

| Charge statute | Charge Description** |

|---|---|

| RCW 9A.42.020 | Criminal mistreatment in the 1st degree |

| RCW 9A.42.030 | Criminal mistreatment in the 2nd degree |

| RCW 9A.42.035 | Criminal mistreatment in the 3rd degree |

| RCW 9A.42.037 | Criminal mistreatment in the 4th degree |

Murder or manslaughter (9A.32.030, 9A.32.060) may be charged due to physical abuse, neglect, or both. Given that, we reviewed files from each case with either of these charges in greater detail to understand the surrounding circumstances and sub-categorize them appropriately.

The complete text of all statutes is available at: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw

Additional Subgroup Analyses

Important insights about the impact of the prosecution of elder mistreatment may also be gathered through comparative analysis of cases categorized into other subgroups. Cases may be categorized using any characteristics of the case, victim, perpetrator, and criminal justice process. These additional analyses allow us to incorporate elements of previously published taxonomies into our analysis. Potentially relevant examples of subgroups that we intend to examine as part of our analysis include: cases where the perpetrator had a fiduciary relationship to the victim, cases that were adjudicated in mental health or drug treatment court, cases where the victim refused to participate in prosecution, cases where the victim was unable to participate in the prosecution, and cases where the victim died before case adjudication.

Results

Using the strategy outlined above and shown in Figure 1, we examined 1,195 cases with a victim aged ≥ 60 filed in Superior Court in King County, Washington from 2008 – 2011. We found 265 elder mistreatment cases based on charges including the domestic violence designation (Search A). We found 6 additional cases based on the abuse of trust aggravator, 25 additional cases based on a vulnerable victim aggravator charged (Search B), and 7 additional cases based on crime(s) charged (Step C). We found 95 additional cases based on victim-defendant relationship (Search D) and 9 additional cases based on co-habitation (Search E).

In total, 407 cases (34% of all cases with victims aged ≥60) were labeled elder mistreatment using this approach. As noted above, these searches need not be conducted in the order we presented. If conducted in a different order, the number of additional cases identified by each search would be different but the total number of cases would be the same.

Of these 407 elder mistreatment cases, we categorized 181 (44% of all elder mistreatment cases) as financial exploitation. Among financial exploitation, we sub-categorized 19 cases as financial crimes, 47 cases as robbery/burglary, 71 cases as crimes commonly related to the theft of assets, and 65 cases as crimes related to the theft of property. We categorized 137 (34%) of elder mistreatment cases as physical abuse and 6 (1%) as sexual abuse. We categorized 63 (15%) of cases as verbal/emotional/psychological abuse. Of these, we sub-categorized 60 as threats/intimidation/harassment and 6 as vandalism. We categorized 13 (3%) of elder mistreatment cases as neglect.

Limitations

We recognize that this approach relies heavily on what crimes were charged, including charge designations, aggravators, and the charges themselves. As significant differences in statutes and charging practices exist among jurisdictions, this represents a significant limitation in our approach. By describing in detail the categories that were created and the Washington state statutes that were included, we hope these categories will be useful to researchers and policymakers in other jurisdictions in conducting similar comparative analyses.

Discussion and Implications

The criminal justice system represents an important component of a community’s response to elder abuse in many cases, but its current role varies widely between communities. Additionally, the impact of prosecution on older adults and defendants is not well understood, and the optimal criminal justice strategies are unclear. Therefore, further research in this area is critical and has the potential to assist prosecutors, policymakers, community-based professionals, and others.

A natural source of data for this research is the administrative data that most jurisdictions are already collecting for the day-to-day management of cases. This data typically includes detailed information about the victim(s), defendant(s), charges, and resolution of cases of crimes against older adults. Systematically analyzing this already existing dataset offers the opportunity to understand prosecutorial decisions and their impact. Also, this data may potentially be linked to other administrative data sources (including police, Adult Protective Services, health care, and community service agency databases) to better understand the multi-disciplinary response. Linking to other data sets also has the potential to illuminate patterns of events that occur in cases referred for prosecution, potentially revealing red flags that may provide opportunities for intervention. Greater knowledge about such red flags might provide information valuable to prevention efforts.

Conducting research with this data may be challenging, though. States and jurisdictions have diverse laws (Mallik-Kane & Zweig, 2015). Even when studying individual states or jurisdictions, many elder abuse cases are prosecuted using previously existing criminal statutes (assault, rape, theft, etc.) rather than elder mistreatment-specific laws (Heisler & Stiegel, 2004; Stiegel, 2017). As a result, the development of a rigorous, systematic methodological approach to identify cases of elder mistreatment and categorize them is an important preliminary step to allow for analysis of criminal justice data. We have proposed here an approach that operationalizes elements of a currently accepted definition of elder mistreatment. Though based on Washington state law, our methodology may be adapted to other jurisdictions.

Using a standardized methodological approach such as ours will allow for the comparative analysis between different time periods and different jurisdictions. This approach may also be useful to prosecutorial offices to decide what data to collect and the best way to capture it when they design and develop new databases or reports. Additionally, it may be helpful to offices in their efforts to launch specialized units devoted to prosecuting elder mistreatment, as such units become more common.

Employing this methodology may be useful when linking criminal justice databases to other administrative data sources to perform additional analyses on the impact of multi-disciplinary intervention.

Ultimately, we believe that a rigorous standardized analytic approach to criminal justice data will assist prosecutors, researchers, policymakers, and others develop a greater understanding of the current as well as optimal role of prosecution as a response to elder mistreatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding Details: This work was supported by the Elder Justice Foundation and the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Tony Rosen’s participation was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grants R03 AG048109, K76 AG054866; the John A. Hartford Foundation; the American Geriatrics Society; the Emergency Medicine Foundation; and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckman R, Callahan J, & Solomon J (2015). Elder Abuse Multi-Disciplinary Teams: Planning for the Future. [Google Scholar]

- Burston GR (1975). Letter: Granny-battering. British Medical Journal, 3(5983), 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MT, Breckman R, Callahan J, Lachs M, Ramsey-Klawsnik H, & Solomon J (2012). The sexual revolution’s last frontier: how silence about sex undermines health, well-being, and safety in old age. Generations, 36(3), 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MT, Brandl B, & Breckman R (2014). The Elder Justice Roadmap: A stakeholder Initiative to respond an emerging health, justice, financial and social crisis. Retrieved from http://ncea.acl.gov/Library/Gov_Report/docs/EJRP_Roadmap.pdf

- Conrad KJ, Iris M, Ridings JW, Fairman KP, Rosen A, & Wilber KH (2011). Conceptual model and map of financial exploitation of older adults. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 23(4), 304–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JM, Xu Y, & Jogerst GJ (2017). Iowa Dependent Adult Abuse Prosecutions From 2006 Through 2015: Health Care Providers’ Concern. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 8(3), 153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goergen T, & Beaulieu M (2013). Critical concepts in elder abuse research. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(8), 1217–1228. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government Accountability Office. (2011). Elder Justice: Stronger Federal Leadership Could Enhance National Response to Elder Abuse. (GAO-11–208). Washington, DC: GAO [Google Scholar]

- Heisler C, & Stiegel L (2004). Enhancing the justice system’s response to elder abuse: Discussions and recommendations of the “Improving Prosecution” working group of The National Policy Summit on Elder Abuse. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 14(4), 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler CJ (2000). Elder abuse and the criminal justice system: New awareness, new responses. Generations-Journal of the American Society on Aging, 24(2), 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler CJ (1991). The Role of the Criminal Justice System in Elder Abuse Cases. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 3(1), 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson MF (1991). Elder mistreatment: A taxonomy with definitions by Delphi. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 3(2), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL (2015). The vexing problem of defining financial exploitation. Journal of Financial Crime, 22(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL, & Hafemeister TL (2013b). How do abused elderly persons and their adult protective services caseworkers view law enforcement involvement and criminal prosecution, and what impact do these views have on case processing? Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 25(3), 254–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krienert JL, Walsh JA, & Turner M (2009). Elderly in America: a descriptive study of elder abuse examining National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) data, 2000–2005. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 21(4), 325–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, & Pillemer KA (2015). Elder Abuse. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(20), 1947–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, & Mosqueda L (2006). Physical abuse of the elderly: the medical director’s response. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 7(4), 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik-Kane K, & Zweig JM (2015). What is elder abuse A taxonomy for collecting criminal justice research and statistical data. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Miller ML, & Johnson JL (2003). Protecting America’s senior citizens: What local prosecutors are doing to fight elder abuse: Bureau of Justice Assistance. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP, & Scott JM (2003). Prosecution of elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation: Criminal liability, due process, and hearsay: Bureau of Justice Assistance. [Google Scholar]

- Mysyuk Y, Westendorp RG, & Lindenberg J (2013). Added value of elder abuse definitions: a review. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(1), 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Policy Forum. (2010). The Elder Justice Act:Addressing Elder Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Policy Forum. (2012). The Basics: Older Americans Act of 1965: Programs and Funding. Retrieved from http://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_OlderAmericansAct_02-23-12.pdf

- National Research Council. (2003). Elder mistreatment: Abuse, neglect and exploitation in an aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro AE, Gassoumis ZD, & Wilber KH (2013). Holding abusers accountable: an elder abuse forensic center increases criminal prosecution of financial exploitation. Gerontologist, 53(2), 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne B (2013). Elder physical abuse and failure to report cases: Similarities and differences in case type and the justice system’s response. Crime & Delinquency, 59(5), 697–717. [Google Scholar]

- Payne B (2010). Understanding Elder Sexual Abuse and the Criminal Justice System’s Response: Comparisons to Elder Physical Abuse. Justice Quarterly, 27(2), 206–224. [Google Scholar]

- Payne B (2002). An integrated understanding of elder abuse and neglect. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(6), 535–547. [Google Scholar]

- Payne B, Blowers A, & Jarvis D (2012). The neglect of elder neglect as a white-collar crime: Distinguishing patient neglect from physical abuse and the criminal justice system’s response. Justice Quarterly, 29(3), 448–468. [Google Scholar]

- Payne B, & Gainey R (2006). The criminal justice response to elder abuse in nursing homes: A routine activities perspective. Western Criminology Review, 7(3). [Google Scholar]

- Payne B, Berg BL, & Toussaint J (2001). The police response to the criminalization of elder abuse: An exploratory study. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 24(4), 605–626. [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin MR (1988). A time for dignity: Police and domestic abuse of the elderly. [Google Scholar]

- Policastro C, Gainey R, & Payne BK (2015). Conceptualizing crimes against older persons: Elder abuse, domestic violence, white-collar offending, or just regular ‘old’crime. Journal of Crime and Justice, 38(1), 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Lachs MS, Bharucha AJ, Stevens SM, Teresi JA, Nebres F, & Pillemer K (2008). Resident-to-resident aggression in long-term care facilities: Insights from focus groups of nursing home residents and staff. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 56(8), 1398–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Pillemer K., Lachs M. (2008). Resident-to-resident aggression in long-term care facilities: An understudied problem. Aggressive Violent Behavior, 13(2), 77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Stern ME, Elman A, & Mulcare MR (2018). Identifying and Initiating Intervention for Elder Abuse and Neglect in the Emergency Department. Clinics of Geriatric Medicine, 34(3), 435–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stannard CI (1973). Old folks and dirty work: The social conditions for patient abuse in a nursing home. Social Problems, 20(3), 329–342. [Google Scholar]

- Stiegel L (2017). Elder Abuse Victims’ Access to Justice: Roles of the Civil, Criminal, and Judicial Systems in Preventing, Detecting, and Remedying Elder Abuse In Dong X (Ed.), Elder Abuse: Research, Practice, and Policy (pp. 343–362): Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Stiegel L, & Klem E (2007). Information about Laws Related to Abuse. Washington, DC: Retrieved from http://www.abanet.org [Google Scholar]

- Uekert B, Keilitz S, Saunders D, Heisler C, Ulrey P, & Baldwin E (2012). Prosecuting elder abuse cases: Basic tools and strategies: National Center for State Courts; Williamsburg, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RB, & Crabb VL (2017). Toward definitions of elder mistreatment In Dong X (Ed.), Elder Abuse: Research, Practice, and Policy (pp. 3–20): Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Legislature. Revised Code of Washington. Retrieved from: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/ [Google Scholar]

- Wolf RS (2008). Victimization of the elderly: elder abuse and neglect. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 2(03), 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf R (1996). Understanding elder abuse and neglect. Aging, 367, 4–9. [Google Scholar]