Abstract

The health of women and children affected by opioid use disorder is a priority for state Medicaid programs. Little is known about longer-term outcomes among Medicaid-enrolled children exposed to opioids in utero. We examined well-child visit use and diagnoses of pediatric complex chronic conditions in the first five years of life among children with opioid exposure, tobacco exposure, or neither exposure in utero. The sample consisted of 82,329 maternal-child dyads in the Pennsylvania Medicaid program in which the children were born in the period 2008–11 and followed up for five years. Children with in utero opioid exposure had a lower predicted probability of recommended well-child visit use at age fifteen months (42.1 percent) compared to those with tobacco exposure (54.1 percent) and those with neither exposure (55.7 percent). Children with in utero opioid exposure had a predicted probability of being diagnosed with a pediatric complex chronic condition similar to that among children with tobacco exposure and those with neither exposure (20.4 percent, 18.7 percent, and 20.2 percent, respectively). Our findings were consistent when we examined a subgroup of opioid-exposed children identified as having neonatal opioid withdrawal symptoms.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) in pregnancy is a chronic disease that is associated with adverse maternal and neonatal health outcomes.1 More than 15 percent of pregnancies affected by OUD end in preterm birth,2 and more than half of children exposed to opioids in utero are identified as having neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a constellation of withdrawal symptoms that can require intensive treatment.3 Exposure to opioids in utero may affect neurological development, thus affecting childhood developmental outcomes.4 Additionally, social factors including poverty and poly-substance exposure may affect outcomes among children exposed to opioids in utero.5,6 Clinical guidelines therefore recommend both medical and social services support for pregnant and parenting women with OUD, including efforts to ensure that children exposed to opioids in utero are connected with well-child care and receive recommended developmental screenings.7 Well-child care is important for the identification and treatment of child health conditions.

There are important gaps in knowledge about the extent to which children with in utero opioid exposure receive well-child care and are identified as having chronic conditions in early childhood. First, prior research focused on children with in utero opioid exposure beyond the neonatal period has been limited almost exclusively to samples drawn from cohort studies or followed up with from clinical trials.8–10 While follow-up studies from clinical trials include precise measurements of opioid exposures and high rates of follow-up, their findings might not be generalizable to the broader population of maternal-child dyads affected by OUD. Specifically, the largest clinical trial tested the effect of methadone versus buprenorphine treatment in pregnancy on child outcomes,11 meaning that its findings are not applicable to women with OUD who do not receive medication treatment. Additionally, the trial excluded women with HIV or concurrent benzodiazepine or alcohol use.11

Second, research that used administrative data to study health care use and outcomes focused on outcomes among children diagnosed with NAS compared to outcomes among children without such a diagnosis. Prior studies have documented higher hospital readmission rates among infants with an NAS diagnosis, compared to those without one12 and increased use of school-based disability services among those diagnosed with NAS in infancy relative to those with no NAS diagnosis.13 However, a sizable proportion of neonates born to women with OUD in pregnancy are not diagnosed with NAS,3 which limits the generaliz-ability of prior research findings to children who were exposed to opioids but not diagnosed with NAS. Research from a Boston cohort examined outcomes among children with in utero opioid exposure. However, opioid exposure was defined as having an NAS diagnosis or maternal self-report of opioid use.14 It is likely that comparing children with and without NAS, without consideration of maternal OUD diagnosis, biases results because of unmeasured confounding.

These gaps in knowledge hinder the development of strategies to improve the health of women and children affected by the opioid epidemic. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to conduct a population-based assessment of well-child visit use and the prevalence of pediatric complex chronic conditions among children from birth through age five years who were born to women with OUD in pregnancy.

Study Data And Methods

DATA AND STUDY POPULATION

We conducted an observational study using administrative health care data on all maternal-child dyads in Pennsylvania Medicaid in the period 2008–16, following Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for the conduct of cohort studies.15 Pennsylvania has the third-highest drug overdose death rate in the US,16 and Medicaid is the primary payer of health care costs associated with OUD during pregnancy.17

Our data included inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, and health care provider data for all enrolled individuals. The study cohort of maternal-child dyads was created by identifying women who had a live birth in the period January 1, 2008–December 31, 2011. Maternal-child dyads were linked based on a family variable, the woman’s date of delivery, and the child’s date of birth, which produced a match rate of 96 percent. Women who had a singleton pregnancy, resided in Pennsylvania throughout the pregnancy, and were enrolled in Medicaid for at least 100 days during pregnancy were included. If women had more than one live birth during the study period, we included only the first birth. Women who were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare (versus only Medicaid) were excluded. Children were included if they were continuously enrolled in Medicaid from birth through age five years, with enrollment gaps of no more than three months in any year. The analytic sample included 82,329 maternal-child dyads.

OPIOID EXPOSURE

We defined in utero opioid exposure as being born to a woman identified at any time in pregnancy or at delivery as having an OUD diagnosis, including women who did and did not receive medication treatment for OUD. We observed few cases (less than 0.2 percent of the entire cohort) of pregnant women having buprenorphine or methadone use without a diagnosis of OUD. Because our definition was based on diagnoses in administrative health care data, we examined maternal-child dyad characteristics to assess face validity. We found few maternal OUD treatment and NAS cases among dyads who were not in the opioid-exposed group, which supported our approach. Additionally, demographic characteristics of the opioid-exposed group were similar to those observed in studies of pregnant women with OUD in other state Medicaid populations.18,19

COMPARISON GROUPS

We created two different comparison groups relative to the opioid-exposed group: tobacco exposed but not opioid exposed, and neither tobacco nor opioid exposed.20 We created a tobacco-exposed comparison group because in utero tobacco exposure is a well-known cause of adverse child health outcomes and is associated with psychosocial risk factors that are similar to those faced by women with substance use but that are not measured in administrative data.21 Furthermore, the majority of women with OUD also smoke tobacco.22 In utero tobacco exposure was defined as being born to a woman diagnosed with tobacco use in pregnancy but not diagnosed with OUD. Our second comparison group consisted of children who had neither observed tobacco nor opioid exposure in utero.

Because some pregnant women have OUD but are not diagnosed as such, we conducted a separate subgroup analysis. We examined outcomes among children with an NAS diagnosis, regard-less of maternal exposure status, relative to those among children with in utero opioid exposure but without an NAS diagnosis. Following prior research, we defined NAS diagnosis based on diagnostic codes, and we excluded cases where withdrawal symptoms were likely due to inhospital treatment of critically ill neonates.23

OUTCOMES

Health care use outcomes included well-child visit use during the first five years. Well-child visit use measures were constructed according to clinical guidelines for the recommended number of visits according to quality metrics endorsed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance.24 First, we constructed a measure of the number of well-child visits in the first fifteen months of life, to assess the probability that children had six or more visits in that time. Second, we constructed a binary measure of whether children had annual well-child visits at ages three, four, and five years. Finally, we used the pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system to determine children’s probability of being diagnosed with any such condition by the end of the five years of follow-up. The classification system provides a measure of the burden and prevalence of chronic conditions in a population, given different background risk factors. The pediatric complex chronic conditions algorithm is a validated measurement system for assessing population-level trends in childhood morbidity.25 A pediatric complex chronic condition is defined as a medical condition that “can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care.”26 Pediatric complex chronic condition categories include neurologic and neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal and urologic, gastrointestinal, hematologic or immunologic, metabolic, other congenital or genetic defect, malignancy, premature and neonatal, technology dependence, and transplantation. (See online appendix exhibit A1 for a further description of the study variables.)27

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All children whose births are covered by Medicaid are eligible for Medicaid for the first year of life,28 although many children were lost to follow-up between ages one and five years because of disenrollment from Medicaid. Children are more likely to stay enrolled in Medicaid if they have low household incomes or poor health status, or if their parents are also enrolled in Medicaid.29–31 In our study population we observed differential loss to follow-up by race, length of maternal Medicaid enrollment, and health status (see appendix exhibit A2).27 To reduce the bias in our estimates due to this differential loss to follow-up, we constructed inverse-probability-of-censoring weights.32 A weight was constructed for each child based on the ratio of the probability that they were not lost to follow-up at age five years and the probability that they were not lost to follow-up conditional on observed characteristics associated with loss to follow-up. (See appendix exhibit A4 for the distribution of the weights and appendix exhibit A3 for weighted and unweighted descriptive statistics.)27 Our weighted statistical analyses reflect outcomes that would have been observed had loss to follow-up been random with respect to observed characteristics, thus reducing potential bias from loss to follow-up.

Weighted descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the study population. We calculated the weighted prevalence and corresponding 95% confidence interval for each pediatric complex chronic condition, overall and by in utero opioid exposure group. We then fit inverse-probability weighted multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the association between in utero opioid exposure and outcomes: well-child visit use and the development of any pediatric complex chronic condition. Based on prior research, we controlled for both maternal-and child-level covariates in all analyses.33 Maternal-level covariates included age at delivery in years (less than 18, 18–34, or 35 or older), mental health disorders, Medicaid eligibility category in pregnancy (disability related versus pregnancy or income related), and Medicaid enrollment (a categorical variable that indicated the number of months enrolled in each year of follow-up). Child-level covariates included sex; race; birthweight in grams (less than 1,500, 1,500–2,499, or 2,500 or more); and rural-area residence, according to rural-urban commuting area codes. We fit population-averaged models with a first-order autoregressive correlation structure and robust standard errors to account for the correlation of error terms within children over multiple observations. Average predicted probabilities of outcomes and associated 95% confidence intervals by exposure group were derived from regression results.34

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

LIMITATIONS

The study had some limitations. First, there may have been some misclassification of in utero opioid exposure, as there are no toxicology testing results available for pregnant women or neonates in Medicaid data and some women with OUD might not be diagnosed. To mitigate the effects of this limitation, we controlled for a range of maternal- and child-level factors that are associated with OUD, and we separately assessed children with an NAS diagnosis in subgroup analyses. Additionally, we note that there is no biochemical “gold standard” validation for neonatal exposure to opioids.4

Second, our study design was descriptive, and we could not make inferences about any causal relationship between in utero opioid exposure and child outcomes. It is possible that an unmeasured confounder, such as low social support, was correlated with both opioid exposure and a reduced likelihood of well-child visit use in the first fifteen months. For those outcomes where we did not find significant differences between children with in utero opioid exposure and other children, an unmeasured confounder would need to be both positively correlated with in utero opioid exposure and negatively correlated with outcomes to change our results.

Third, some study subjects were lost to follow-up. We implemented inverse-probability weighting to minimize bias from loss to follow-up.

Fourth, if health services use was lower among opioid-exposed children, there would have been fewer opportunities to identify pediatric complex chronic conditions. This means that the prevalence of those conditions could be under-reported.

Fifth, because of underreporting of smoking status, some children with in utero tobacco exposure might have been misclassified as having neither opioid nor tobacco exposure. However, our primary comparison groups of interest were those with tobacco exposure but no opioid exposure, versus those with exposure to both.

Finally, these results might not be generalizable to populations not enrolled in Medicaid or to Medicaid populations in other states.

Study Results

Among the weighted 82,443 Medicaid-enrolled children born in Pennsylvania during 2008–11 and followed up for five years, we identified3.2 percent (weighted n = 2,627) with in utero opioid exposure and 19.2 percent (weighted n = 15,790) with in utero exposure to tobacco but not opioids, with the remaining 76.7 percent (weighted n = 64,026 not exposed to either opioids or tobacco in utero (exhibit 1). Relative to the overall population, children with in utero opioid exposure were more likely to be non-Hispanic white (84.8 percent versus 52.2 percent), have a birthweight of less than 2,500 grams (12.7 percent versus 5.7 percent), and have a mother with a mental health condition diagnosis (68.2 percent versus 28.5 percent).

Exhibit 1.

Weighted descriptive characteristics of Pennsylvania Medicaid-enrolled maternal-child dyads at baseline, overall and by in utero opioid and tobacco exposure status

| In utero exposure to: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall | Opioids | Tobacco | Neither |

| Unweighted N | 82,329 | 2,627 | 16,492 | 63,210 |

| Weighted N | 82,443 | 2,627 | 15,790 | 64,026 |

| CHILD CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 48.8% | 49.5% | 49.1% | 48.7% |

| Male | 51.2 | 50.5 | 50.9 | 51.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 52.2 | 84.8 | 67.1 | 47.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 30.9 | 9.4 | 22.6 | 33.8 |

| Hispanic | 12.7 | 4.1 | 8.0 | 14.2 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 4.2 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 4.8 |

| Birthweight | ||||

| 2,500 grams or more | 94.3 | 87.2 | 93.2 | 94.9 |

| 1,500–2,499 grams | 4.6 | 11.1 | 5.6 | 4.1 |

| Less than 1,500 grams | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| Neonatal abstinence syndrome diagnosis | 2.6 | 57.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Rural residencea | 13.4 | 19.8 | 17.0 | 12.3 |

| MATERNAL CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Mean age at delivery, years (SE) | 25.2 (0.02) | 26.8 (0.09) | 25.4 (0.04) | 25.1 (0.02) |

| Mental health conditionb | 28.5% | 68.2% | 58.6% | 19.5% |

| Medication treatment for OUDc | 1.9 | 52.9 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Mean months of Medicaid enrollment in first year after birth (SE) | 10.4 (0.02) | 11.4 (0.05) | 10.7 (0.03) | 10.3 (0.02) |

| Medicaid eligibility category | ||||

| Disability | 6.9% | 12.0% | 8.4% | 6.3% |

| Pregnancy or income | 93.1 | 88.0 | 91.6 | 93.7 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data about 82,329 Medicaid-enrolled children born in the period 2008–11 and followed up for five years.

NOTES In utero opioid exposure is defined as having a maternal diagnosis of opioid use disorder (OUD) at any time in the pregnancy. In utero tobacco exposure is defined as having a maternal diagnosis of tobacco use at any time in the pregnancy but no diagnosis of OUD. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is defined as having a diagnosis of a constellation of withdrawal symptoms. All analyses were weighted for the inverse probability of being lost to follow-up. SE is standard error.

Residence in a rural ZIP code, based on rural-urban commuting area codes.

Defined as having a diagnosis of depression or a major depressive disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder at any time in the pregnancy.

Defined as initiating methadone or buprenorphine for treatment of OUD at any time in the pregnancy.

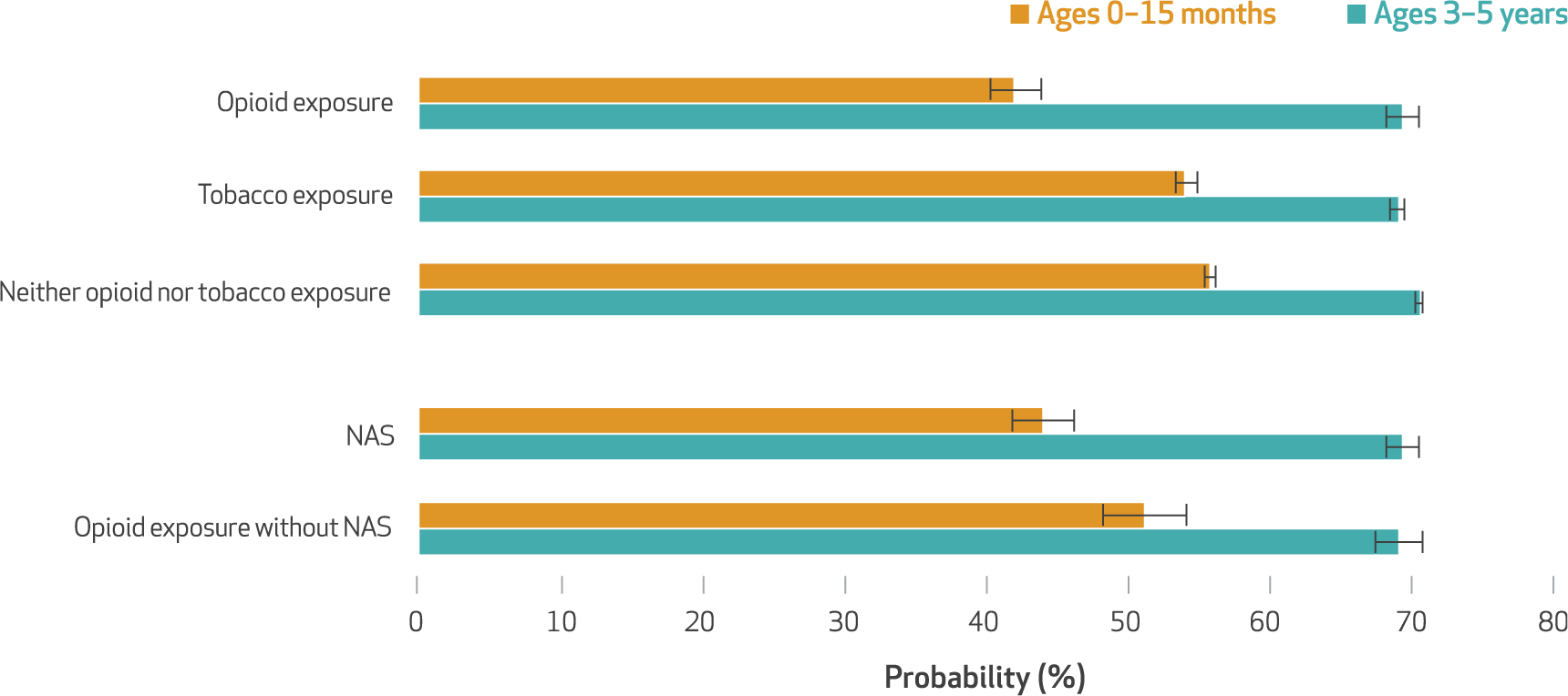

Children with in utero opioid exposure had an average predicted probability of attending the recommended number of well-child visits at ages 0–15 months of 42.1 percent, which was significantly lower than the average predicted probability among children with tobacco but not opioid exposure in utero (54.1 percent) (exhibit 2). Children with neither exposure had a predicted probability of having the recommended number of visits of 55.7 percent. Children diagnosed with NAS had a significantly lower predicted probability (44.1 percent), compared to that for children with in utero opioid exposure but no diagnosis of NAS (51.2 percent). There were no significant differences in annual well-child visit use at ages 3–5 years between children with in utero opioid exposure (69.3 percent) and those with tobacco but not opioid exposure (69.0 percent) or those with neither exposure (70.6 percent). Likewise, there were no significant differences in annual well-child visit use at ages 3–5 years between children with a diagnosis of NAS and those with in utero opioid exposure but no NAS diagnosis (69.3 percent and 69.1 percent, respectively).

Exhibit 2.

Average predicted probability of having recommended well-child visits among children in Pennsylvania Medicaid, by in utero exposure to opioids or tobacco and diagnosis of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS)

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data about 82,329 Medicaid-enrolled children born in the period 2008–11 and followed up for five years.

NOTES In utero opioid exposure and in utero tobacco exposure are defined in the notes to exhibit 1. NAS is defined as having a diagnosis of a constellation of withdrawal symptoms. At least six well-child visits are recommended in the first fifteen months of life, and an annual well-child visit is recommended at ages three, four, and five years. The results are from weighted population-averaged multivariable logistic regression models that controlled for maternal and child health characteristics. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

In an unadjusted analysis we found that19.9 percent of children were diagnosed with any pediatric complex chronic condition by age five years (exhibit 3). When we compared children with in utero opioid exposure to those with in utero tobacco exposure or those with neither exposure, we found a significantly greater prevalence of premature and neonatal complex chronic conditions: 3.9 percent of children with in utero opioid exposure had such a condition, compared to 1.9 percent of those with in utero tobacco exposure and 2.0 percent with neither exposure.

Exhibit 3.

Weighted prevalence of pediatric complex chronic conditions (CCCs) at ages 0–5 years among children in Pennsylvania Medicaid, overall and by in utero opioid and tobacco exposure status

| In utero exposure to: | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Opioids | Tobacco | Neither | |||||

| Pediatric CCC | % | 95% Cl | % | 95% Cl | % | 95% Cl | % | 95% Cl |

| Cardiovascular | 5.6 | 5.4, 5.7 | 6.8 | 5.9, 7.8 | 5.4 | 5.1, 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.4, 5.7 |

| Other congenital or genetic defect | 4.4 | 4.3, 4.6 | 4.5 | 3.7, 5.3 | 4.2 | 3.9, 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.3, 4.6 |

| Hematologic or immunologic | 3.8 | 3.6, 3.9 | 1.9 | 1.4, 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.4, 2.9 | 4.1 | 4.0, 4.3 |

| Metabolic | 3.4 | 3.2, 3.5 | 3.3 | 2.6, 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.7, 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.3, 3.6 |

| Neurologic and neuromuscular | 3.3 | 3.1, 3.4 | 4.2 | 3.5, 5.0 | 3.1 | 2.9, 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.1, 3.4 |

| Respiratory | 2.2 | 2.1, 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.9, 3.1 | 2.2 | 2.0, 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0, 2.2 |

| Premature and neonatal | 2.1 | 2.0, 2.2 | 3.9 | 3.2, 4.6 | 1.9 | 1.7, 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.9, 2.1 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.4 | 1.3, 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.1, 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.3, 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3, 1.5 |

| Malignancy | 1.4 | 1.3, 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.1, 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.4, 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.4 |

| Renal and urologic | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.5, 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.4 |

| Technology dependence | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.1, 2.0 | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.2, 1.4 |

| Transplantation | —a | —b | —a | —b | —a | —b | —a | —b |

| Any pediatric CCC | 19.9 | 19.6, 20.2 | 21.6 | 20.1, 23.2 | 19.1 | 18.5, 19.7 | 20.0 | 19.7, 20.4 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data about 82,329 Medicaid-enrolled children born in the period 2008–11 and followed up for five years.

NOTES All analyses were weighted for the inverse probability of being lost to follow-up. In utero opioid exposure and in utero tobacco exposure are defined in the notes to exhibit 1. CI is confidence interval.

Data on transplantation are not shown because the sample size was smaller than eleven.

Not applicable.

Children with in utero opioid exposure had a predicted probability of being diagnosed with a pediatric complex chronic condition of 20.4 percent, which was similar to the predicted probability among children with only in utero tobacco exposure (18.7 percent) and that among children with neither exposure (20.2 percent) (exhibit 4). However, the probability of being diagnosed with a pediatric complex chronic condition among children with a diagnosis of NAS was24.2 percent, higher than that among children with in utero opioid exposure but no NAS diagnosis (19.2 percent). Neonatal complex chronic conditions may be correlated with NAS diagnosis. For example, respiratory diseases are considered to be such conditions, and respiratory disturbances are scored on the Finnegan scale—a widely used system to identify cases of NAS.7 Therefore, we replicated our analyses after excluding neonatal complex chronic conditions from the definition of pediatric complex chronic conditions. The results were similar in magnitude and direction to the results of our original analysis. However, the probability of having a pediatric complex chronic condition, excluding neonatal, among children with a diagnosis of NAS was not significantly different from those with opioid exposure and no NAS diagnosis (19.4 percent and 16.1 percent, respectively).

Exhibit 4.

Average predicted probability of developing a pediatric complex chronic condition (CCC) by age 5 years among children in Pennsylvania Medicaid, by in utero exposure to opioids or tobacco and diagnosis of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS)

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data about 82,329 Medicaid-enrolled children born in the period 2008–11 and followed up for five years.

NOTES In utero opioid exposure and in utero tobacco exposure are defined in the notes to exhibit 1. NAS is defined as having a diagnosis of a constellation of withdrawal symptoms. The results are from weighted population-averaged multivariable logistic regression models that controlled for maternal and child health characteristics. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Among children enrolled in Pennsylvania Medicaid, those with in utero opioid exposure had lower probabilities of receiving the recommended number of well-child visits in the first fifteen months of life, relative to those without opioid exposure. However, we found no meaningful differences between children with in utero opioid exposure and other children in well-child visits at ages 3–5 years and few differences in the probability of developing any pediatric complex chronic condition by age five. A subgroup of children who were diagnosed with NAS had well-child visit use rates similar to those among children with any in utero opioid exposure but no NAS diagnosis. The children diagnosed with NAS had a small increase in the probability of being diagnosed with any pediatric complex chronic condition by age five years, compared to those with in utero opioid exposure but no NAS diagnosis. The strengths of this study include our ability to reduce bias from socioeconomic confounding factors by identifying exposure and comparison groups in the same state Medicaid program and our ability to examine maternal OUD exposure separately from an NAS diagnosis.

Well-child visit use is recognized as an important measure of health care quality.35 Clinical guidelines recommend follow-up for children who are exposed to opioids in utero, with a particular emphasis on well-child visits.7 While we did not observe a higher rate of well-child visit use among children with in utero opioid exposure, relative to children without such exposure, it is notable that fewer than half of the opioid-exposed children had had the recommended number of well-child visits at age fifteen months. Ideally, all children would have the recommended well-child visit use, but such utilization is highly variable—ranging from 29 percent to 81 percent in different state Medicaid programs.36 We did not find substantial differences in the probability of being diagnosed with a pediatric complex chronic condition by age five years when we compared children with in utero opioid exposure to other groups.

In subgroup analyses that compared children diagnosed with NAS to those with opioid exposure but not an NAS diagnosis, the findings were consistent with our overall results. In general, children diagnosed with NAS had lower well-child visit use at age fifteen months than those with opioid exposure but no NAS diagnosis, but there were no differences between the groups in well-child visit use at ages 3–5 years. Children with a diagnosis of NAS had a higher probability of being diagnosed with a pediatric complex chronic condition, compared to children with in utero opioid exposure but no NAS diagnosis. This difference appeared to be largely due to the diagnosis of neonatal chronic conditions, as children with an NAS diagnosis and those with opioid exposure but no diagnosis had similar probabilities of being diagnosed with other pediatric complex chronic conditions. Neonatal complex chronic conditions—in particular, respiratory diseases—are likely correlated with the NAS diagnosis. It is plausible that a diagnosis of NAS is a proxy for social risk factors that are associated with increased likelihood of screening at the time of birth, rather than a purely biological risk factor for adverse health status.

Our findings are consistent with those of a study of ninety-six children exposed to methadone or buprenorphine in pregnancy, which found that the children’s growth and cognitive development at age three years were within normal ranges.10 Our findings are also largely consistent with those of a Boston cohort study in which in utero opioid exposure was associated with lack of normal physiological development but was not associated with an increased risk of emotional disturbance or attention deficit hyper-activity disorder.14 In contrast, a study of children in the Tennessee Medicaid program found that an NAS diagnosis was associated with subsequent educational disabilities among children ages 3–8 years.13 Several differences between the Tennessee cohort and ours could explain the different results. First, the Tennessee study focused on special education services and not pediatric complex chronic conditions, and psychosocial risks of exposure to OUD may differ entially affect the need for special education services relative to the development of a chronic condition. Second, the Tennessee study focused on an NAS diagnosis as an exposure, as opposed to our approach of studying all children with in utero opioid exposure. While the Tennessee study used matching techniques to identify a comparison group for children with NAS diagnoses, our subgroup analyses directly compared children with NAS diagnoses to children with in utero opioid exposure but no NAS diagnosis.

Conclusion

In this study of children from birth through age five years who had in utero opioid exposure, we found lower health care use relative to other children, but few meaningful differences in the diagnosis of any pediatric complex chronic condition. Subgroup analyses suggest that children diagnosed with NAS have higher probabilities of being diagnosed with a pediatric complex chronic condition, relative to children with in utero opioid exposure but without an NAS diagnosis—primarily because of neonatal conditions. Although we did not detect a large magnitude of association between in utero opioid exposure and pediatric chronic conditions, the rate of chronic conditions was high among all children in our study. Our results point to the multifaceted nature of exposures—including substance use, poverty, and social circumstances—that shape the health of children in Medicaid. ▪

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was partially supported by an agreement among the University of Pittsburgh, the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Award Nos. K23DA038789 to Elizabeth Krans and R01DA045675 to Marian Jarlenski and Krans). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors are grateful to the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services for use of the Medicaid data and feedback on prior versions of this article. The authors thank Leah Klocke, research coordinator at Magee-Womens Research Institute, for her contributions.

Footnotes

Our results point to the multifaceted nature of exposures that shape the health of children in Medicaid.

Contributor Information

Marian P. Jarlenski, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, in Pennsylvania..

Elizabeth E. Krans, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and at the Magee-Womens Research Institute, in Pittsburgh..

Joo Yeon Kim, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health..

Julie M. Donohue, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health..

A. Everette James, III, Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health..

David Kelley, Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, in Harrisburg..

Bradley D. Stein, RAND Corporation in Pittsburgh..

Debra L. Bogen, Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine..

NOTES

- 1.Krans EE, Patrick SW. Opioid use disorder in pregnancy: health policy and practice in the midst of an epidemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1): 4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baer RJ, Chambers CD, Ryckman KK, Oltman SP, Rand L, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Risk of preterm and early term birth by maternal drug use. J Perinatol. 2019;39(2):286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudak ML, Tan RC. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2): e540–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behnke M, Smith VC. Prenatal substance abuse: short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e1009–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarlenski M, Barry CL, Gollust S, Graves AJ, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Kozhimannil K. Polysubstance use among US women of reproductive age who use opioids for nonmedical reasons. Am J Public Health. 2017; 107(8):1308–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozhimannil KB, Admon LK. Structural factors shape the effects of the opioid epidemic on pregnant women and infants. JAMA. 2019;321(4): 352–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical guidance for treating pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder and their infants [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2018. [cited 2019 Dec 6]. (HHS Pub.No. [SMA] 18–5054). Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma18-5054.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldacchino A, Arbuckle K, Petrie DJ, McCowan C. Neurobehavioral consequences of chronic intrauterine opioid exposure in infants and preschool children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konijnenberg C, Melinder A. Prenatal exposure to methadone and buprenorphine: a review of the potential effects on cognitive development. Child Neuropsychol. 2011; 17(5):495–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaltenbach K, O’Grady KE, Heil SH, Salisbury AL, Coyle MG, Fischer G, et al. Prenatal exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: early childhood developmental outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones HE, Fischer G, Heil SH, Kaltenbach K, Martin PR, Coyle MG, et al. Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research (MOTHER)—approach, issues, and lessons learned. Addiction. 2012; 107(Suppl 1):28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrick SW, Burke JF, Biel TJ, Auger KA, Goyal NK, Cooper WO. Risk of hospital readmission among infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):513–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fill MA, Miller AM, Wilkinson RH, Warren MD, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, et al. Educational disabilities among children born with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2018; 142(3):e20180562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azuine RE, Ji Y, Chang HY, Kim Y, Ji H, DiBari J, et al. Prenatal risk factors and perinatal and postnatal outcomes associated with maternal opioid exposure in an urban, low-income, multiethnic US population. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6): e196405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose deaths [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [last reviewed 2019 Jun 27; cited 2019 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkelman TNA, Villapiano N, Kozhimannil KB, Davis MM, Patrick SW. Incidence and costs of neonatal abstinence syndrome among infants with Medicaid: 2004–2014. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clemans-Cope L, Lynch V, Howell E, Hill I, Holla N, Morgan J, et al. Pregnant women with opioid use disorder and their infants in three state Medicaid programs in 2013–2016. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019; 195:156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachhuber MA, Mehta PK, Faherty LJ, Saloner B. Medicaid coverage of methadone maintenance and the use of opioid agonist therapy among pregnant women in specialty treat ment. Med Care. 2017;55(12): 985–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Benjamin T, Wachman EM, O’Grady KE. Prenatal opioid exposure, neonatal abstinence syndrome/neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, and later child development research: shortcomings and solutions. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):90–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams KE, Melvin CL, Raskind-Hood CL. Sociodemographic, insurance, and risk profiles of maternal smokers post the 1990s: how can we reach them? Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(7):1121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones HE, Heil SH, Tuten M, Chisolm MS, Foster JM, O’Grady KE, et al. Cigarette smoking in opioid-dependent pregnant women: neonatal and maternal outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(3):271–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000–2009. JAMA. 2012; 307(18):1934–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Child and adolescent well-care visits (W15, W34, AWC) [Internet]. Washington (DC): NCQA;c 2019. [cited 2019 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/child-and-adolescent-well-care-visits/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):E99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 28.Mann C State health official letter on the implementation of the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2009. August 31 [cited 2019 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho-08-31-09b.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkataramani M, Pollack CE, Roberts ET. Spillover effects of adult Medicaid expansions on children’s use of preventive services. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20170953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pati S, Calixte R, Wong A, Huang J, Baba Z, Luan X, et al. Maternal and child patterns of Medicaid retention: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Medicaid enrollment gap length and number of Medicaid enrollment periods among US children. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):e55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Lau B, Napravnik S, Eron JJ Jr. Selection bias due to loss to follow up in cohort studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):91–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, Greene MF. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the March of Dimes Foundation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 130(1):10–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43(3):962–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hakim RB, Bye BV. Effectiveness of compliance with pediatric preventive care guidelines among Medicaid beneficiaries. Pediatrics. 2001; 108(1):90–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Well-child visits in the first 15 months of life [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): 2018. [cited 2019 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/scorecard/well-child-visits-first-15-months-of-life/index.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.