Abstract

Background and objectives

Since December 2019, the rapid epidemic spread of COVID-19 in China has aroused the attention of the government and the public. The purpose of this study is to investigate the attitude and knowledge among medical students and non-medical students toward SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

A web-based survey was disseminated to the students from medical colleges and comprehensive universities via the survey website (www.wjx.cn) and via WeChat. Participation in the study was voluntary with the instruction to click on the website or scan the QR code to complete the anonymous electronic questionnaire from February 5 to 7, 2020.

Results

The questionnaire was completed by 588 students from 20 colleges and universities in China. Of the respondents, 66.0% were medical students and 34.0% were non-medical students. 99.6 % of the students held an optimistic attitude toward the COVID-19 epidemic situation. The majority of participants had a good level of knowledge of common symptoms, transmission, and prevention of the disease. In a comparison between non-medical students with medical students, the medical students had a deeper understanding of COVID-19. In this study, we also found that female students had a better understanding of transmission and prevention than male students did.

Conclusions

The majority of students who participated in the questionnaire had a positive attitude and a good perception about COVID-19.

Keywords: 2019 novel coronavirus, Attitude and knowledge, Medical and non-Medical students

Introduction

In December 2019, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was first reported in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [1]. It was caused by the seventh member of enveloped RNA coronavirus, which is currently named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [[2], [3], [4]]. Coronaviruses (CoV) are a large family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the common cold to severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) [5,6]. Common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, and breathing difficulties. Most patients have mild symptoms and good prognosis, although severe cases present with pneumonia, severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and even death [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Epidemiological and clinical data provided evidence that human-to-human transmission could occur within a family and at the hospital [[11], [12], [13], [14]], and SARS-CoV-2 has a stronger infectious capability than SARS-CoV, but a lower mortality than SARS-CoV [14,15].

As of February 28, 2020, the epidemic had subsequently spread through the whole country, particularly Wuhan and other areas in Hubei Province, which had the vast majority of cases. The Chinese government has been taking stringent and effective measures to prevent and control COVID-19. Additionally, the mainstream media including TV, newspapers, posters, internet-based resources and social networks widely publicized the scientific knowledge on COVID-19 and reported the epidemic situation in a timely manner to increase public awareness.

To date, a few publications have investigated the practice, cognition, and attitude of residents of varying ages in the outbreak [16]. It is needful for school administrators to understand the students’ response in the face of public health emergency. The goal of this study is to investigate the attitude, knowledge, and cognition toward SARS-CoV-2 infection among medical students and non-medical students, and thus to provide a reference for schools to take more effective measures to protect the physical and mental health of students throughout the epidemic period.

Methods

Study design

The questionnaire was designed by respiratory physicians, medical teachers, and scientists. The survey featured multiple choice questions that were intended to measure the attitude toward the outbreak and the knowledge of clinical symptoms, the modes of transmission, and the methods of prevention of the disease. It was noted in the questionnaire that some general information about COVID-19, which was not confirmed currently, might be answered based on the participators’ cognition. It consisted of mainly five sections: (1) Attitude; (2) Knowledge of clinical symptom; (3) Knowledge of transmission; (4) Knowledge of prevention; and (5) Cognition of general information of COVID-19. We needed to measure the knowledge of clinical symptoms, transmission, prevention, and cognition of students regarding COVID-19, in which the options Yes or No against each set of questions were evaluated. To verify the attitude of students, options were presented: very optimistic, cautiously optimistic and pessimistic.

Data collection

This study was an anonymous and web-based survey. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Medical University. Written informed consent was not required because the questionnaire survey of the students was anonymous and had less than minimal risk.

A pretest of the questionnaire was carried out by ten male and ten female students from different institutes of Guangzhou Medical University for their feedback to identify the questionnaire’s reasonableness. The finalized online questionnaire was uploaded to wenjuanxing (http://www.wjx.cn), one of the most popular online survey platforms in China, and a QR code was generated [17,18]. The survey was then disseminated to the students from medical colleges and comprehensive universities via the survey website itself and via a popular Chinese social media channel (WeChat) by the authors on February 5th. It was completely voluntary for the participants of the study to click on the website or scan the QR code to complete the electronic questionnaire. It was also suggested that the participants send the QR code to their students’ online communication group. The data were collected through the platform from February 5th to 7th. If the questionnaire had complete answers and a response time over 90 s, it was regarded as valid.

Data analysis

Data entry and analysis were performed using SPSS v.26 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY). The chi-square test was used to describe the statistical differences between the two groups and between the genders. P values < 0.05 indicated that a difference was statistically significant.

Results

588 valid questionnaires were collected. Study participants were from 20 colleges and universities (such as Guangzhou Medical University and Guangdong Medical University, South China University of Technology, Sun Yet-Sen University, Shenyang University, Hangzhou Normal University, Jiamusi University). The student majors included Medicine, Engineering, Natural Science, Management, Economics, Law, Education, Philosophy, Agronomy, etc. Among the 588 students, males and females were 190 of 588 (32.3%) and 398 of 588 (67.7%), respectively. Of the participants, 66.0% were medical students and 34.0% were non-medical students. In the medical student group, 118 (30.4%) were male and 270 (69.6%) were female. Similarly, in the non-medical student group, the proportion of females was also in the majority (64%).

The attitude toward COVID-19 of the two groups of students is shown in Table 1 . All the students focused on the latest news of COVID-19. 73.6% of the participants regarded COVID-19 as a very dangerous disease, the percentage of female non-medical students was the highest at 83.6%, whereas the percentage of male non-medical students was the lowest at 66.7%. Encouragingly, 99.6% of the students had an optimistic attitude toward the COVID-19 endemic situation. There was no statistically significant difference in the questions between two groups.

Table 1.

Attitude to COVID-19.

| Medical college students |

Non-medical college students |

χ2 | P value** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males N(%) | Females N(%) | Males N(%) | Females N(%) | |||

| Do you follow the latest news of COVID-19? | ||||||

| Rarely | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 2.050 | 0.152 |

| Sometimes | 15(12.7) | 41(15.2) | 15(20.8) | 23(18.0) | ||

| Always | 103(87.3) | 229(84.8) | 57(79.2) | 105(82.0) | ||

| χ 2 | 0.407 | 0.246 | ||||

| P value* | 0.524 | 0.620 | ||||

| Risk perception | ||||||

| Very dangerous | 83(70.3) | 195(72.2) | 48(66.7) | 107(83.6) | 2.327 | 0.127 |

| Moderately dangerous | 35(29.7) | 75(27.8) | 24(33.3) | 21(16.4) | ||

| Not dangerous | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | ||

| χ 2 | 0.143 | 23.191 | ||||

| P value* | 0.705 | <0.000* | ||||

| Attitude to effective control | ||||||

| Very optimistic | 70(59.3) | 156(57.8) | 50(69.4) | 74(57.8) | 4.935 | 0.085 |

| Cautiously optimistic | 48(40.7) | 114(42.2) | 21(29.2) | 53(41.4) | ||

| Pressimistic | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(1.4) | 1(0.8) | ||

| χ 2 | 0.081 | 3.041 | ||||

| P value* | 0.776 | 0.219 | ||||

Chi-square test for difference between genders.

Chi-square test for difference between medical students and non-medical students.

Table 2 shows that all the students had knowledge about common clinical symptoms of COVID-19 whereas the groups showed a lower level of knowledge of the rare clinical presentations of COVID-19. Among medical students of both genders, there was an overall agreement in responses to all questions, and they were more knowledgeable regarding the questions: low fever, mild fatigue, diarrhea, and symptomless infection as untypical clinical performance of COVID-19 than non-medical students. Among non-medical students, 25.8% of females responded with the correct answer to the question in which symptomless infection as rare clinical performance, in comparison, only 12.5% of males answered correctly.

Table 2.

COVID-19 clinical symptoms description.

| Medical college students |

Non-medical college students |

χ2 | P value** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males N(%) | Females N(%) | Males N(%) | Females N(%) | ||||

| Clinical symptoms | |||||||

| Fever, fatigue, dry cough | Yes | 118(100) | 268(99.3) | 71(98.6) | 128(100) | 0.000 | 1 |

| No | 0(0) | 2(0.7) | 1(1.4) | 0(0) | |||

| Low fever, mild fatigue | Yes | 81(68.6) | 185(68.5) | 40(55.6) | 81(63.3) | 3.808 | 0.051 |

| No | 37(31.4) | 85(31.5) | 32(44.4) | 47(36.7) | |||

| Diarrhea | Yes | 63(53.4) | 185(68.5) | 33(45.8) | 71(55.5) | 7.801 | 0.005** |

| No | 55(46.6) | 85(31.5) | 39(54.2) | 57(44.5) | |||

| Symptomless | Yes | 38(32.2) | 112(41.5) | 9(12.5) | 33(25.8)* | 18.72 | 0.000** |

| No | 80(67.8) | 158(58.5) | 63(87.5) | 95(74.2)* | |||

Chi-square test for difference between genders.

Chi-square test for difference between medical students and college students.

Table 3 shows the knowledge of the mode of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the two groups. Similarly, no statistical significance was observed. The participants had a good level of knowledge of the common modes, such as “by coughing and sneezing” (100%), “by touching the eyes, nose, and mouth” (88.8%), and “by taking public transportation” (64.1%). As for in response to the unconfirmed transmission mode during the investigation, in which “by the fecal-oral route”, “by touching elevator buttons and doorknobs”, and “by handshaking”, 75%, 70.2%, and 45.9% of students answered in the affirmative, respectively. This suggests that students were cautious to the unknown. Similarly to the results of Table 2, there was the same level of knowledge between the genders in medical students.

Table 3.

Questions of knowledge about transmission of COVID-19.

| Medical college students |

Non-medical college students |

χ2 | P value** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males N(%) | Females N(%) | Males N(%) | Females N(%) | ||||

| Way for transmission | |||||||

| By coughing and sneezing | Yes | 118(100) | 270(100) | 72(100) | 128(100) | ||

| No | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | |||

| By handshaking | Yes | 55(46.6) | 120(44.4) | 29(40.3) | 66(51.6) | 0.305 | 0.581 |

| No | 63(53.4) | 150(55.6) | 43(59.7) | 62(48.4) | |||

| By taking public transportation | Yes | 75(63.6) | 181(67.0) | 39(54.2) | 82(64.1) | 1.722 | 0.189 |

| No | 43(36.4) | 89(33.0) | 33(45.8) | 46(35.9) | |||

| By touching elevator buttons and door knobs | Yes | 89(75.4) | 186(68.9) | 42(58.3) | 96(75)* | 0.222 | 0.638 |

| No | 29(24.6) | 84(31.1) | 30(41.7) | 32(25)* | |||

| By the fecal-oral route | Yes | 86(72.9) | 211(78.1) | 49(68.1) | 95(74.2) | 1.455 | 0.228 |

| No | 32(27.1) | 59(21.9) | 23(31.9) | 33(25.8) | |||

| By touching eyes, nose and mouth | Yes | 104(88.1) | 246(91.1) | 60(83.3) | 112(87.5) | 2.343 | 0.126 |

| No | 14(11.9) | 24(8.9) | 12(16.7) | 16(12.5) | |||

Chi-square test for difference between genders.

Chi-square test for difference between medical students and non-medical students.

As shown in Table 4 , students in the two groups had a good knowledge of protection against virus transmission. Over 95% of the students acquired the knowledge of the main preventive measures that are to “wear mask, wash hands frequently, spend less time outside, and avoid contact with patients”. Nevertheless, 85.3% of students were aware of the importance of avoiding or touching the nose, eyes, and mouth with unwashed hands”. More females than males in the two groups gave the correct answer to this question.

Table 4.

Question of knowledge of prevention towards COVID-19.

| Medical college students |

Non-medical college students |

χ2 | P value** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males N(%) | Females N(%) | Males N(%) | Females N(%) | ||||

| Method | |||||||

| Wear a mask | Yes | 118(100) | 270(100) | 71(98.6) | 127(99.2) | 1.502 | 0.220 |

| No | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(1.4) | 1(0.8) | |||

| Wash hands frequently | Yes | 116(98.3) | 270(100) | 69(95.8) | 127(99.2) | 1.597 | 0.206 |

| No | 2(1.7) | 0(0) | 3(4.2) | 1(0.8) | |||

| Spend less time outside | Yes | 113(95.8) | 270(100)* | 69(95.8) | 128(100) | 0.000 | 1 |

| No | 5(4.2) | 0(0)* | 3(4.2) | 0(0) | |||

| Avoid contact with infected people | Yes | 114(96.6) | 265(98.1) | 67(93.1) | 122(95.3) | 4.063 | 0.044** |

| No | 4(3.4) | 5(1.9) | 5(6.9) | 6(4.7) | |||

| Avoid touching nose, eyes, and mouth | Yes | 98(83.1) | 237(87.9) | 57(79.2) | 110(85.9) | 0.853 | 0.356 |

| No | 20(16.9) | 33(12.1) | 15(20.8) | 18(14.1) | |||

Chi-square test for difference between genders.

Chi-square test for difference between medical students and non-medical students.

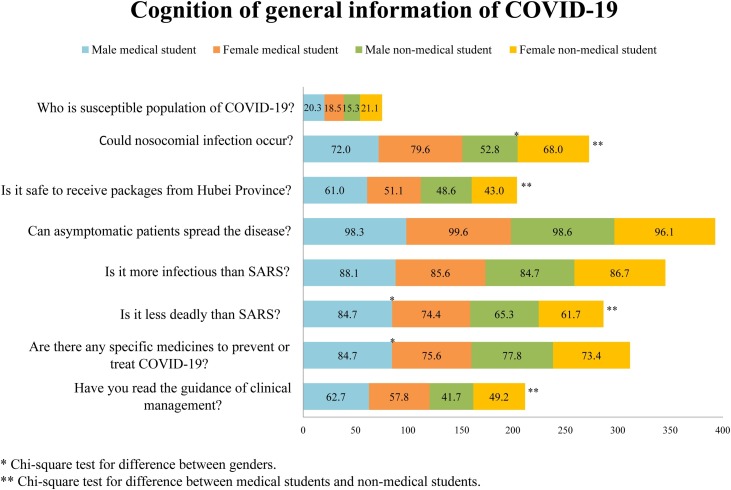

Fig. 1 shows the cognition of general information of COVID-19. The answers to questions of general information regarding COVID-19 were based on cognition. In response to the questions: “Are there any specific medicines to prevent or treat COVID-19?”, “Who is a susceptible population to COVID-19?”, “Can asymptomatic patients spread the disease?”, and “Is it more infectious than SARS?”, there was no statistical significance between the two groups. Most of students thought that young people were not a susceptible population, which led to 81% of the participants’ failure to answer the question. However, more medical students responded with the correct answer to the questions in which “Could nosocomial infection occur?”, “Is it safe to receive packages from Hubei Province?”, and “Is it less deadly than SARS?”. Moreover, more medical students had read the guidance of clinical management to deal with the disease. These findings indicate that they had a deeper knowledge of COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Students' cognition of general information of COVID-19.

Discussion

Since COVID-19 emerged in Wuhan in December 2019, it has rapidly spread around the country and the world. The confirmed cases had reached 78,630 with 2747 fatalities in China by February 28th, 2020 [15], suggesting a SARS-CoV-2 infection with strong transmissibility and universal susceptibility.

On account of the rapid spread and the increase of death associated with COVID-19 in China, it became the focus of public concern in understanding how to carry out precautionary measures both on the individual and community levels. The goal of the current study was to investigate only the attitude and level of comprehension about COVID-19 among medical students and non-medical students. The data showed that almost all of the students who participated in the questionnaire expressed optimism that COVID-19 would be controlled, even though they were fully aware of the high risk of COVID-19.

All of students who participated in the survey were eager to get access to the most up-to-date information available in the media and internet regarding COVID-19, thereby to have a good level of perception about the disease. Although comparison between non-medical students and medical students in response to the most knowledge about COVID-19 revealed no significant difference, there was a difference in response to the questions answered on the basis of the deeper understanding, such as “Is it safe to receive a package from Hubei province?”, and “Could nosocomial infection occur?”. Additionally, over 59% of medical students had read the guidance of clinical management. Such differences can possibly be explained by the fact that medical students might be inclined to update their medical knowledge and cognition of COVID-19 from research articles, academic media, and lectures. Unexpectedly, 46.5% of non-medical students had read the guidance of clinical management, which further indicated that the students with different majors had a positive attitude toward the outbreak and preferred to gather more knowledge regarding COVID-19. We further found that there was a disparity in the level of knowledge about transmission and prevention between the genders, it seems that female students were more cautious in response to the questions they were uncertain about.

Based on the findings of this study, the recommendation could be given to increase awareness of protective hygiene among the students more regularly, particularly for non-medical students, even though both medical and non-medical students participated in the survey were eager to acquire knowledge about COVID-19 during the outbreak. Meanwhile, it is necessary for medical colleges to improve the educational programs of teaching and scientific research that encourage students to apply what they have learned theoretically from textbooks into practice.

Funding

No funding sources.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the students who have participated in this study.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus implication of virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J.J., Dong X., Cao Y.Y., Yuan Y.D., Yang Y.B., Yan Y.Q. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;(February) doi: 10.1111/all.14238. PubMed PMID:32077115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milne-Price S., Miazgowicz K.L., Munster V.J. The emergence of the middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Pathog Dis. 2014;71(2):121–136. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin Y., Wunderink R.G. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology. 2018;23(2):130–137. doi: 10.1111/resp.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu K., Fang Y.Y., Deng Y., Liu W., Wang M.F., Ma J.P. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(9):1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K., Chu H., Yang J. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phan L.T., Nguyen T.V., Luong Q.C., Nguyen T.V., Nguyen H.T., Le H.Q. Importation and human-to-human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):872–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng S.Q., Peng H.J. Characteristics of and public health responses to the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):575. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J., Zhao S., Teng T., Abdalla A.E., Zhu W., Xie L. Systematic comparison of two animal-to-human transmitted human coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Viruses. 2020;12(2):244. doi: 10.3390/v12020244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi Y., Chen L.H., Zhang L., Yang Y.Y., Zhan S.Y., Fu C.X. Public practice, attitude and knowledge of coronavirus disease. J Tropical Medicine. 2020;20(2):145–149. China. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu C., Hu Y., Fu Q., Governor S., Wang L., Li C. Physician mental workload scale in China: development and psychometric evaluation. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu G., Shi Y., Yan Y., Li Y., Han J., Li G. The prevalence of and factors associated with willingness to utilize HTC service among college students in China. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1050. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5953-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]