Abstract

Conducting palliative care research can be personally and professionally challenging. Although limitations in funding and training opportunities are well described, a less recognized barrier to successful palliative care research is creating a sustainable and resilient team. In this special report, we describe the experience and lessons learned in a single palliative care research laboratory. In the first few years of the program, 75% of staff quit, citing burnout and the emotional tolls of their work. To address our sustainability, we translated resilience theory to practice. First, we identified and operationalized shared mission and values. Next, we conducted a resilience resource needs assessment for both individual team members and the larger team as a whole and created a workshop-based curriculum to address unmet personal and professional support needs. Finally, we changed our leadership approach to foster psychological safety and shared mission. Since then, no team member has left, and the program has thrived. As the demand for rigorous palliative care research grows, we hope this report will provide perspective and ideas to other established and emerging palliative care research programs.

Key Words: Resilience, burnout, palliative care, research team, staff, professional

Key Message

Conducting palliative care research can be emotionally challenging work for members of the research team. Investing in both team and individual resilience resources may promote job satisfaction and facilitate program sustainability.

Introduction

The demand for palliative care science is emerging rapidly. In the past decade, the number of peer-reviewed palliative care publications has expanded exponentially, several dedicated and successful palliative care research organizations have been established, interest in funding palliative care research and training has grown, and national organizations have established academic meetings focused specifically on palliative care science.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Despite its importance, conducting palliative care research is challenging. Limitations in both funding and research training opportunities are well described.6, 7, 8, 9 A less-recognized barrier to palliative care research, however, is that of creating a sustainable research team. Just as a palliative care clinical team is inherently multidisciplinary, so too is the palliative care research team. In both settings, recognition of the shared and unique contributions of team members is necessary for success.10 And, just as palliative care clinical practice may be inherently challenging because of the emotional exhaustion and burnout experienced by clinicians,11 so too is the conduct of palliative care research. In both settings, attention to staff resilience is necessary.

Our palliative care and resilience research laboratory was founded in 2014. In its first two years, three of four staff quit, citing the emotional toll of conducting palliative care research. Nearly all members of the team experienced some degree of emotional distress, anxiety, or burnout. In the ensuing years, we developed internal procedures to build team resilience and sustainability. The objective of this special report is to share our lessons learned and strategies for improvement. Our hope is that this report provides perspective and ideas to other established and emerging palliative care research programs.

Key Concepts

Working with patients with serious illness and their families can be emotionally challenging

Palliative care research is inherently broad and includes basic (bench) sciences, clinical and translational research, and population-based epidemiologic studies. Our program focuses on clinical (patient-centered) research and more specifically on interventions designed to build resilience, alleviate suffering, and improve quality of life. Conducting our studies involves direct contact with patients and families in the form of project coordination, survey-based data collection, patient-based and family based interviews, and intervention delivery. Hence, our team includes diverse research staff (clinical research coordinators [CRCs] and interventionists), methodologists (biostatisticians and qualitative research analysts), and both early and senior career faculty (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Hypothetical Members of a Palliative Care Research Team

| Title | Select Roles & Responsibilities | Examples of Stressors and Burnout Risks |

|---|---|---|

| CRC |

|

|

| Interventionist |

|

|

| Biostatistician |

|

|

| Qualitative analyst |

|

|

| Early career investigators |

|

|

| Program manager |

|

|

| Program director |

|

|

CRC = clinical research coordinator.

When we launched the laboratory, all team members understood that our research participants would be patients who were seriously ill and family members who might be distressed and/or bereaved. Where team members struggled, however, was with the emotional tolls of witnessing and vicariously living with serious illness (Table 1). Specifically, patient and family experiences reminded team members of their own previously suffered losses and traumas. CRCs, interventionists, and qualitative analysts who spent time working directly with patients and families shared that their built relationships were meaningful for both themselves and the research participants. They felt unprepared to navigate processes of grief and bereavement when patients became more seriously ill or died. They mourned the loss of relationships when studies ended. Both qualitative analysts and biostatisticians who were otherwise removed from direct patient contact still reported the jarring emotional impact of observing illness and death secondhand.12

Many of our CRCs and interventionists came into their positions with limited work experience; few had prior life experience with seriously ill patients. They reported a sense of imposition when interacting with ill or distressed patients and families (Table 1). They shared that not knowing if or when patients would die provoked severe anxiety. In contrast, some of our interventionists and qualitative analysts had more extensive training and life experience. For them, the challenges revolved around navigating tensions between adhering an intervention or interview script vs. responding skillfully to patient or family emotions in real time. They shared that maintaining role identity and creating professional boundaries were struggles.

The stressors of early and later career investigators were often different from those of other study staff (Table 1). Here, sources of stress tended to center on career development, including securing funding for research studies and publishing the results. Compounding these challenges were the philosophical processes of early academic careers, including establishing long-term goals and career identities. Often for the first time, early career investigators felt responsible for their own future. Many started their careers in a clinical field being inspired to do research based on what they observed. Now they were learning to balance clinical and research roles, responsibilities to themselves and their team, and the sense that they were in the defining moments of their career.

Finally, senior investigators felt unprepared to navigate the stress of establishing and leading the research program (Table 1). Indeed, few senior investigators have formal training or mentorship in skills, such as human resources, advocacy, team building, strategic planning, or budget management; most arrive in their leadership roles based on academic productivity and seniority.13, 14, 15 In our case, the senior investigators were simultaneously learning to manage and support the team's emotional struggles and career development needs. The added degree of staff turnover created challenges for budgets and productivity. Errors were made, projects were stalled, and team morale was low. Taken together, the program's sustainability was at risk.

Burnout is Common

The necessity of addressing burnout among palliative care clinicians is well established.11 , 16 Briefly, burnout is a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress.17 It is characterized by feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion, mental distancing or negativity related to work, and reduced professional efficacy. The evolution and relative prevalence of each of these experiences vary. In the palliative care community, burnout is predominantly characterized by energy depletion and corresponding emotional exhaustion.11 Individual factors associated with higher burnout include nonwhite race, female sex, and younger age.18, 19, 20 Workplace factors associated with higher burnout exist at the systems level (e.g., productivity-based performance evaluations) and job level (e.g., lack of control over schedule).11 , 18, 19, 20, 21

Burnout is commonly accompanied by related experiences of moral distress and compassion fatigue.18 Moral distress is the experience of psychological distress in response to a situation where a worker feels disempowered to do what they believe to be the morally appropriate action because of real or perceived job constraints.22 Compassion fatigue is not, as the name would imply, an exhaustion of compassion toward others. Rather, it is a type of secondary traumatic stress defined by the emotional strain of working with those who are suffering from the consequences of traumatic events like serious illness.23

Taken together, palliative care researchers are at high risk for burnout, moral distress, and compassion fatigue. Consider the experience of the young CRC who feels an obligation to complete certain tasks or has little control over their schedule. Consider the experience of the interventionist who feels a need to resist their psychology training in responding to a patient's distress, instead focusing on adhering to an intervention script. Consider the biostatistician who distances themselves from the work because it was reminiscent of their own trauma. Consider the qualitative analyst who vicariously experiences and then carries the grief of bereaved parents. Consider the early career investigator who constantly struggles with their uncertain future. Consider the program leader who feels responsible for the whole team.

Importantly, burnout, moral distress, and compassion fatigue are not necessarily persistent. Although they certainly may be resolved with a job change or change in workplace responsibilities, they can also be addressed with targeted coping strategies.24

Resilience Can Be Learned and Promoted

We define resilience as the process of harnessing the resources needed to sustain well-being in the face of stress or adversity.25, 26, 27 This definition is grounded in resilience theory and decades of our and other teams' research. Indeed, during adversities as variable as illness, natural disaster, poverty, and war, people tend to draw from the same three buckets of resilience resources:1 individual resources (e.g., personal characteristics, such as grit, hardiness, humor, optimism, and skills such as stress management, mindfulness, goal setting, and self compassion);2 community resources (e.g., social networks, support from peers, family, or faith communities); and, existential resources (e.g., skills in reappraisal and reframing what matters, the search for meaning and purpose, the ability to reflect and learn lessons after adversity).25

Which bucket of resilience resources most helps which person or group is highly variable. Hence, two key aspects of building resilience are identifying one's go-to buckets (where do I already have resilience resources?, or more simply, what do I do that helps me navigate tough times?), and, diversifying one's resilience resource portfolio (which of these buckets is relatively empty, and how can I fill it?) Asking these questions implies not only that the process of resilience must be deliberate but also that resilience can be learned.25

Finally, it is important to note that resilience, like burnout, is fluid.25 The process evolves over time and may vary depending on the type of adversity. Resilience is not the opposite of burnout, rather, it may buffer the impact of burnout or it may be what we leverage to weather experiences like burnout. In our experience, the first phase of the process of resilience is recognizing the stressor and then normalizing and accepting our emotional response to it. We call this phase “getting through.” This is a particularly important phase for navigating challenging feelings like moral distress and compassion fatigue. Experiencing them does not mean we are not resilient. It means we are currently, and perhaps with good reason, having a hard time. A key to successfully getting through is a culture of psychological safety. Leaders who demonstrate vulnerability, compassion, integrity, transparency, and commitment to their people can more successfully support team members in this phase.

We call the second phase of resilience the “harnessing resources” phase. This is when we contemplate how to move forward. Here, actions and thoughts must be deliberate and might include cultivating skills in stress management, emotional awareness, mindfulness, self-compassion, goal setting, and cognitive reframing. This phase takes work, time, and practice. To support their teams, leaders may need to prioritize these skills and create opportunities for team members to develop them.25

The third and final phase of resilience, “looking back and learning,” comes when we are able to reflect on the impact of an experience on our identities, goals, and values. It is when we note the lessons we learned, the perspectives we gained, the things for which we are not grateful, and the ways in which we want to comport ourselves in the future. Here, leaders can facilitate this phase by providing opportunities for shared reflection and identity building.25

We target resilience in our palliative care research program because we believe it is a pathway to achieving palliative care's goals of alleviating suffering and improving quality of life. Once we recognized that our team was struggling, we also recognized that our team's resilience resource buckets demanded attention.

How a Palliative Care Research Program Operationalized Resilience

Identify the Why

Business and executive literature suggest that full and selfless focus on the best interests of individual colleagues and employees is the best way to inspire commitment and ensure success.28 Helping individuals and teams identify their meaning, purpose, passion, and direction facilitates engagement and productivity.

With this in mind, we gathered perspectives and conducted a series of workshops to identify individual and shared needs, goals, and values. As a group, we decided that the mission of our palliative care research program was to develop evidence-based interventions to promote resilience, alleviate suffering, and improve quality of life among children with serious illness and their families. We broadly defined interventions to include formal protocoled packages like our resilience training program, as well as tools to support communication, decision making, psychosocial and spiritual needs, and symptom management among both patients and families and health care personnel. We then explored how each member of the research program could align their own personal mission with that of our shared work.

Next, the full research team identified six team core values to serve as the foundation for our culture (Fig. 1 ). These were intended to reflect individual and shared priorities; they would become operating principles in both routine activities like weekly meetings, as well as in milestone activities like performance evaluations. They included collaboration—deliberately including team members from different roles on all projects to enhance teamwork and sense of support; career development—deliberately sharing career goals within the team and helping each other to thrive; community—deliberately recognizing the diverse contributions and responsibilities of all team members as equally valuable and necessary parts of a whole; compassion—deliberately nurturing the needs of research participants and each other; courage—deliberately taking risks, asking questions, pushing discovery, and speaking truth; refusing to be bystanders to inequity or injustice; and, commitment—deliberately modeling integrity, accountability, reliability, and efficiency.

Fig. 1.

Palliative care and resilience team core values. Team core values were determined by team consensus and designed to meet both individual and collective missions. These were then incorporated into routine tasks (weekly meetings highlight one core value per week) and milestones (annual performance evaluations include assessments of how team members are working by these values).

Finally, we endeavored to model these values in all individual and group interactions. The values of collaboration and community, for example, meant that all team members (including senior and early career faculty, trainees, CRCs, interventionists, and methodologists) presented their work at research program meetings. This communicated the value that every single person's voice and contribution matter. The value of career development meant that a significant portion of all supervisory one-on-one meetings focused on where people wanted to go and how leaders and the team could help them get there. This resulted in CRCs applying to graduate school, staff receiving leadership development training and being promoted to leadership positions, and the creation of new team member lead programs such as writing groups or miniretreats.

The values of compassion and courage were modeled when leaders, and then other team members, shared and normalized their struggles, frustrations, emotions, and burnout. Leaders openly discussed fears of failure, explored how to take risks in research and professional settings, and how they were experiencing or trying to interrupt bias and discrimination. The value of commitment was similarly modeled with routine, open, and honest communication about programmatic and institutional-level initiatives, stressors, evolving goals, and challenges. Periodic team meetings were devoted to calendaring and goal setting as a group, with clear dates and project leads to promote accountability.

Identify the What

After establishing our mission and values, we conducted an assessment of the team's resilience resources using the framework of our prior research.26 , 29 Notably, group or organizational resilience resources may be different from individual resources.25 As a group, instead of asking “who helps me when times are tough?” we asked, “how do we help each other?” We followed these questions with an exploration of what we should do to bolster each category of resources.

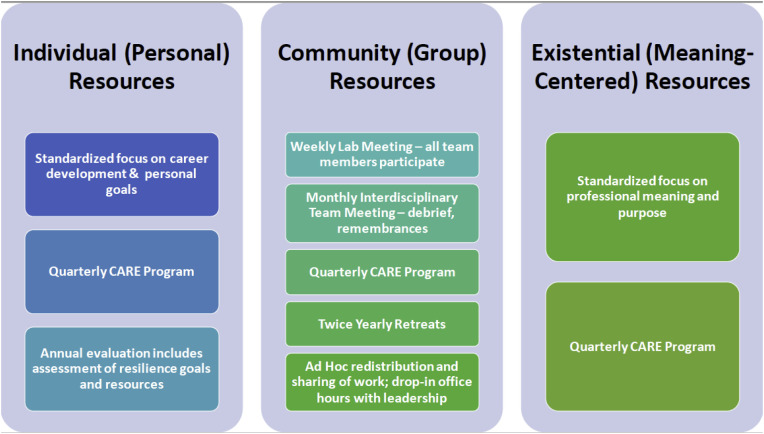

Finally, we created a plan that integrated attention to each of these categories for both individual members of the research program as well as for the whole group (Fig. 2 ). For example, we recognized that individual (personal) resources would strengthen with consistent focus on how to meet each person's career development goals. Developing individual and group skills in stress management and self-care provided a buffer to the invariable stressors palliative care research teams experience. Group support for bereavement and difficult encounters bolstered the team's community (group) resilience resources, and attention to individual and group sense of purpose strengthened existential resources. Creating a norm where all group members felt empowered to speak during meetings facilitated a sense of community and recognition that our diversity of perspective and experience made us stronger.

Fig. 2.

Resilience resources (buckets) and program applications to team resilience. Programmatic plan to build staff and team-based resilience resources based in evidence-based categories of individual, community, and existential resources. Each box represents an implemented practice within the palliative care research team. CARE = Check, Act, Resilience, Engagement.

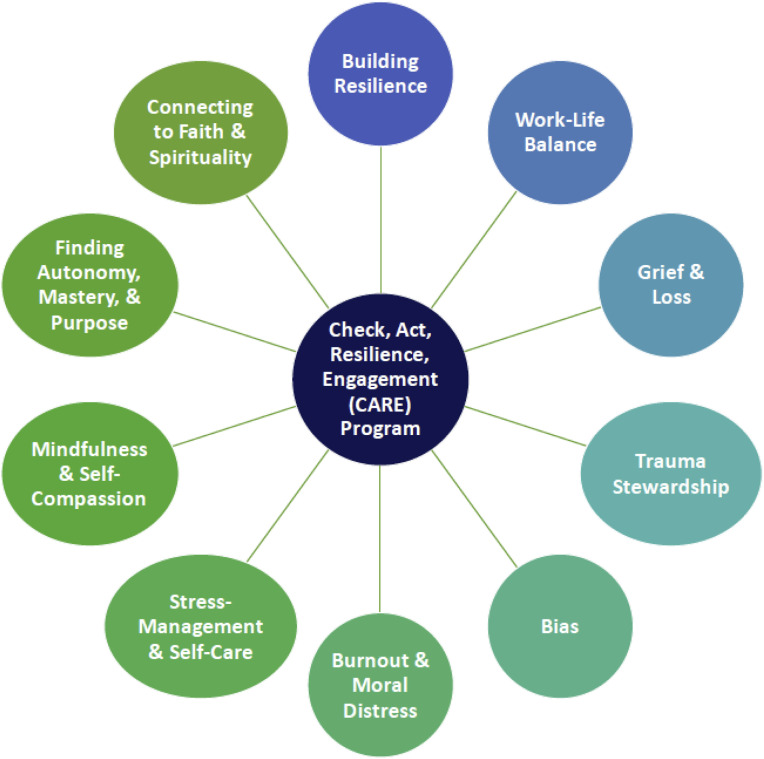

Identify the How

Ultimately, we needed to determine how to creatively foster team resilience and fill our respective resilience resource buckets. Leveraging the multidisciplinary expertise of the team, we designed and implemented a curriculum called Check, Act, Resilience, Engagement (CARE; Fig. 3 ). Briefly, CARE sought to address the needs we most often heard were unmet on the team: dealing with grief and loss, maintaining work-life balance, recognizing and navigating burnout, strategies for stress management and self-care, skills in mindfulness and self-compassion, and integrating religion, spirituality, and the search for meaning and purpose into our daily work. Since then, it has expanded to include new challenges as they arise within the team and our broader community. In the past year, for example, we held workshops focused on trauma stewardship, the experience of bias, racism, and sexual harassment, the stress and uncertainties brought on by coronavirus disease 2019, and how to be antiracist.

Fig. 3.

Check, Act, Resilience, Engagement curriculum modules. Topics developed by team consensus. For each session, staff volunteer to learn and then teach back to team with workshop activities facilitated by program leadership, including trained psychologist, social worker, and faculty experts in each topic.

CARE topics are addressed as brief workshops during research program meetings as often as once quarterly and in more depth at twice-annual retreats. Team members share the responsibility of signing up for a topic they have either experienced, want to learn about, or both. They work independently or with internal or external mentors, based on their preference and style, to present the topic and provide a foundation for open discussion and shared resilience building. Materials from each presentation are archived and available to the team. To date, the program has been feasible and highly valued.

Pay Attention to Evolving Needs and Adapt

Since the implementation of our shared mission, core values, and procedures to build resilience in 2017, our team has had zero turnover because of burnout or distress. We have, however, experienced turnover for other reasons: two of our first CRCs left to attend graduate school with celebration from the rest of the team. Each person has continued to remotely join research program meetings for learning and professional development, citing the culture as critically helpful to their learning. Other staff have successfully shifted their roles to meet career development goals. Additional change has been in growth; several students who started as volunteers applied for entry-level CRC or interventionist jobs on the team, and we have tripled in size. Moreover, the program now supports several early palliative care researchers and clinicians across the country. All members routinely participate in research program and other meetings.

Our leadership team has grown, too, and includes members representing the various professional roles of our team, including CRCs, interventionists, methodologists, and investigators. Where it may seem that the increased activities created to build our team's resilience would increase the leadership workload, our experience has been the opposite. Investing in team well-being paid off; turnover is lower, and engagement, productivity, and sense of commitment are higher. For example, as part of our five-year anniversary, we asked all team members to answer the question: In one word, what do you most appreciate about the Palliative Care and Resilience Research program? Twenty-three members responded and provided answers like community, compassion, courage, and passion (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Palliative Care and Resilience lab member (N = 23) responses to the question: In one word, what do you most appreciate about the palliative care and resilience laboratory? Larger word font reflects more frequent response.

Conclusion

In the first few years after we launched our palliative care research program, burnout, moral distress, compassion fatigue, and turnover were high. To address our sustainability and create a thriving team, we translated resilience theory to practice by identifying and championing shared mission and values, building group resilience resources, and targeting unmet needs. Since then, we have come together, grown, and flourished. We weathered the first phase of the resilience process (getting through). Now, we are in a constant iterative cycle between the second two phases (harnessing resources and looking back). We have not learned everything we need to know or how to solve every problem; we have an approach that enables us to continue to learn and reflect together. Our conclusion? Conducting palliative care research can be personally and professionally challenging. Targeting person and program resilience helps champion the fact that it is also highly rewarding and meaningful work.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This project was not supported by a particular funding mechanism; however, the authors thank the University of Washington and the Seattle Children's Research Institute for support from the Arnold Smith Endowed Fund for early stage investigators (awarded to Dr. Rosenberg to support the launch of the laboratory). Drs. Rosenberg, Steineck, Lau, and Rosenberg are supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants: R01 CA222486 and R01 CA225629 [Rosenberg]; 5T32HL125195 [Steineck]; 5K12 HL137940 [Lau]; and R01 DK121224 [Yi-Frazier]). The opinions presented here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.NCBI PubMed Search for “Palliative Care”. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=palliative+care Available from.

- 2.National Palliative Care Research Center. http://www.npcrc.org/ Available from.

- 3.Palliative Care Research Center. https://palliativecareresearch.org/ Available from.

- 4.Pediatric Palliative Care Research Network. https://www.dana-farber.org/research/departments-centers-and-labs/departments-and-centers/department-of-psychosocial-oncology-and-palliative-care/research/pediatric-palliative-care-research-network/ Available from.

- 5.American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine State of the Science Meeting. http://aahpm.org/meetings/state-of-the-science-meeting Available from. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kross E.K., Rosenberg A.R., Engelberg R.A., Curtis J.R. Postdoctoral research training in palliative care: lessons learned from a T32 program. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59:750–760.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown E., Morrison R.S., Gelfman L.P. An update: NIH research funding for palliative medicine, 2011-2015. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:182–187. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelfman L.P., Du Q., Morrison R.S. An update: NIH research funding for palliative medicine 2006 to 2010. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:125–129. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfman L.P., Morrison R.S. Research funding for palliative medicine. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:36–43. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renger D., Miche M., Casini A. Professional recognition at work: the protective role of esteem, respect, and care for burnout among employees. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62:202–209. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamal A.H., Bull J.H., Wolf S.P. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59:e6–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickson-Swift V., James E.L., Kippen S., Liamputtong P. Risk to researchers in qualitative research on sensitive topics: issues and strategies. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:133–144. doi: 10.1177/1049732307309007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frich J.C., Brewster A.L., Cherlin E.J., Bradley E.H. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:656–674. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr P.L., Raj A., Kaplan S.E., Terrin N., Breeze J.L., Freund K.M. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the national faculty survey. Acad Med. 2018;93:1694–1699. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sklar D.P. Leadership in academic medicine: purpose, people, and programs. Acad Med. 2018;93:145–148. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamal A.H., Wolf S.P., Troy J. Policy changes key to promoting sustainability and growth of the specialty Palliative Care Workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:910–918. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/ Available from.

- 18.Hlubocky F.J., Taylor L.P., Marron J.M. A call to action: Ethics Committee roundtable recommendations for addressing burnout and moral distress in oncology. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:191–199. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanafelt T.D., Noseworthy J.H. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanafelt T.D., Hasan O., Dyrbye L.N. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanafelt T.D., Dyrbye L.N., West C.P., Sinsky C.A. Potential impact of burnout on the US Physician Workforce. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1667–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzeng E., Curtis J.R. Understanding ethical climate, moral distress, and burnout: a novel tool and a conceptual framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:766–770. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-007905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Figley C.R. Brunner/Mazel; Taylor and Francis; London, England: 1995. Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanafelt T.D., Dyrbye L.N., West C.P. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317:901–902. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg A.R. Cultivating deliberate resilience during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg A.R., Yi-Frazier J.P. Commentary: resilience defined: an alternative perspective. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41:506–509. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Southwick S.M., Bonanno G.A., Masten A.S., Panter-Brick C., Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tjan A.K. What the best mentors do. Harvard Business Review 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/02/what-the-best-mentors-do?referral=03759&cm_vc=rr_item_page.bottom Available from.

- 29.Rosenberg A.R. Seeking professional resilience. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172388. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]