Abstract

We report a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) case with rheumatoid arthritis taking iguratimod. The patient who continued iguratimod therapy without dose reduction was treated with ciclesonide had an uneventful clinical course, but prolonged detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was observed after resolution of symptoms. The effects of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and ciclesonide on clinical course and viral shedding remain unknown and warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Iguratimod, Ciclesonide, Viral shedding

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has spread rapidly across the world, yet investigations of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatologic disease taking disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) with immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive effects remain scarce [1]. Here we report a case of COVID-19 in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis taking iguratimod, who had prolonged viral RNA presence.

2. Case report

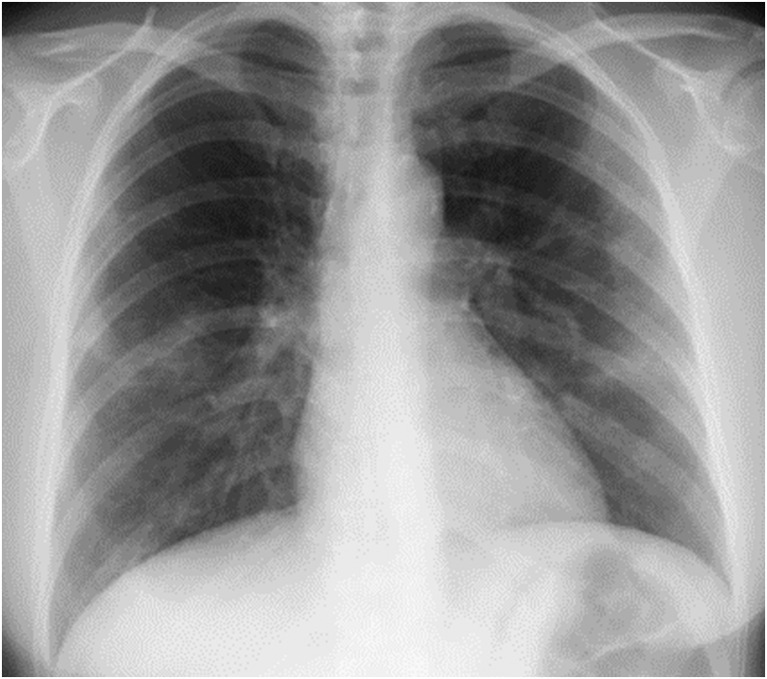

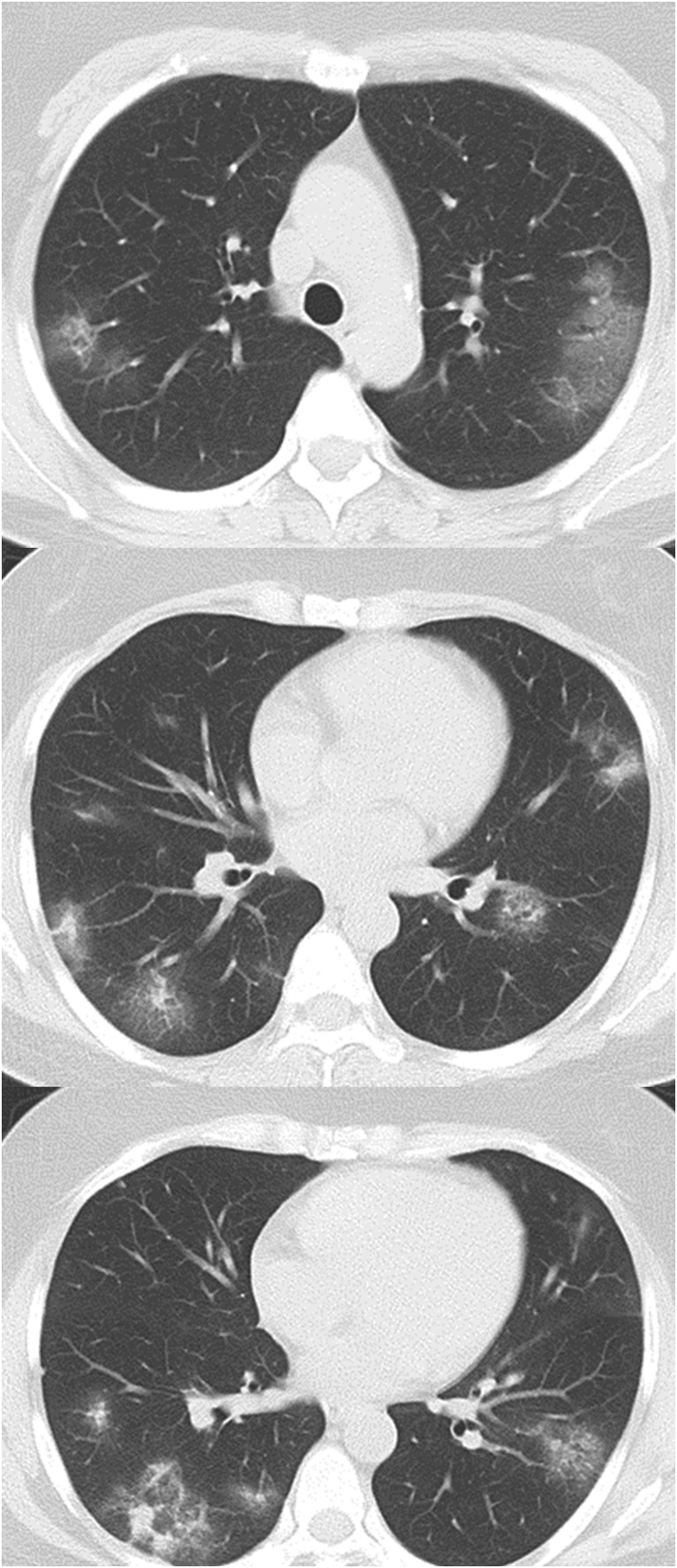

A woman in her 40s with rheumatoid arthritis treated with iguratimod 25 mg twice a day was admitted to Tohoku University Hospital, Sendai, Japan, with a diagnosis of COVID-19 based on real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (real-time RT-PCR) with primers that target the N2 gene of SARS-CoV-2 as described previously [2] from nasopharyngeal swabs and sputum. The patient had developed a fever of up to 38.0 °C, with a cough, sputum production, anosmia and ageusia 5 days before admission, and was looking after herself at home. She was tested for SARS-CoV-2 since her intimate partner was confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 the day before the patient's admission. The patient lived with the partner until 13 days before admission, but subsequently avoided contact after the partner developed a cough. The patient rarely left her house, and so had no close contact with anyone except the partner. On admission, her temperature was 36.9 °C. Blood pressure was 109/96 mmHg, pulse was 95 bpm, respiratory rate was 24 breaths/min and SpO2 was 96% in room air. Initial clinical examination revealed a weight of 76 kg, height of 161 cm, and a body mass index of 29 kg/m2. She was fully conscious and had no pallor or yellow staining of the palpebral conjunctiva. Her heart sounds were normal, with no murmur detected. Upon auscultation, fine crackles could be heard during inspiration in both dorsal lower lung fields. Blood chemistry analyses revealed the following: white blood cell count, 3600/μL; neutrophil count, 2820/μL; lymphocyte count, 600/μL; red blood cell count, 386 × 106/μL; hemoglobin, 11.6 g/dL; hematocrit, 34.0%; platelet count, 126,000/μL; total bilirubin, 0.4 mg/dL; glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, 19 IU/L; glutamic pyruvic transaminase, 9 IU/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 202 IU/L; γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, 21 IU/L; blood urea nitrogen, 7 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.60 mg/dL; creatine phosphokinase, 59 IU/L; prothrombin time, 97.0%; activated partial thromboplastin time, 38.1 s; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 59 mm/h; C-reactive protein (CRP), 11.19 mg/dL; procalcitonin, 0.03 ng/mL; ferritin, 50.2 ng/mL; soluble IL-2 receptor, 663 IU/mL. Chest X-ray showed decreased transparency outside the both middle lung fields (Fig. 1 ). Computed tomography of the chest showed different sizes of patchy ground-glass opacities and infiltrative shadows in peripheral regions of each lobe of both lungs, with elevated intensity of both findings observed in some areas (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

The chest X-ray on admission. Decreased transparency outside the both middle lung fields were shown.

Fig. 2.

The chest Computed tomography on admission. Patchy ground-glass opacities and infiltrative shadows in each lobe of both lungs, with elevated intensity of both findings observed in some areas were observed.

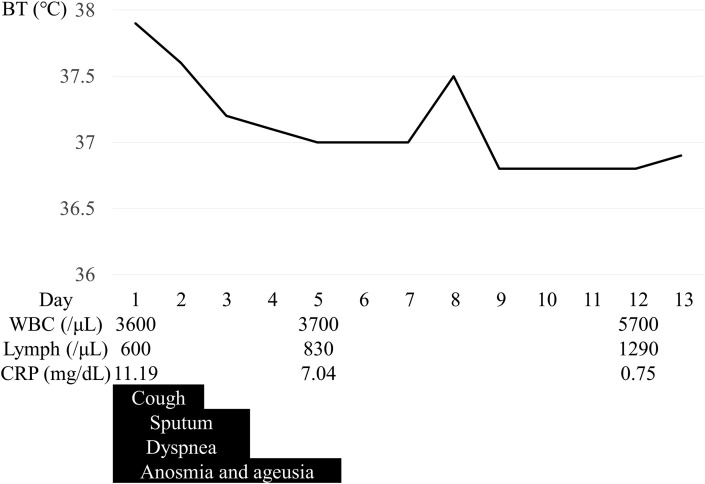

The patient was started on inhaled ciclesonide 400 μg twice a day upon admission. Oral iguratimod was continued at 25 mg twice a day. Fever of 37.5 °C or higher was observed until the second day of hospitalization, then temperature remained at around 37.0 °C degrees after the third day (Fig. 3 ). The cough almost disappeared on the second day of hospitalization, and the sputum on the third day. The patient occasionally complained of dyspnea on exertion and at rest after admission, but this disappeared after the third day of hospitalization. Taste and smell disturbances persisted until the fifth day of hospitalization, but disappeared thereafter. No significant deterioration of arthritis was seen during the course.

Fig. 3.

Clinical course of the present case. Fever of 37.5 °C or higher was observed until the second day of hospitalization, then temperature remained at around 37.0 °C degrees after the third day. Lymphocyte count and CRP had improved from 600/μL and 11.19 mg/dL on admission to 1290/μL and 0.75 mg/dL on the 12th day after admission respectively. The cough, sputum, dyspnea, and anosmia and ageusia disappeared on the second, thired, thired and fifth day of hospitalization, respectively.

A chest X-ray taken on the 12th day after admission showed that the shadows in both lower lung fields had disappeared. Blood tests on this day showed that lymphocyte count and CRP had improved to 1290/μL and 0.75 mg/dL, respectively.

Since the patient's symptoms improved and the possibility of relapse was considered low, the patient was transferred to a nearby hospital on the 13th day after initial admission. Ciclesonide was administered for a total of 14 days. Although the symptoms did not return after transfer, PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 from nasopharyngeal swabs remained positive until 10 days after transfer (27 days after onset). The patient was discharged when PCR tests were confirmed to be negative 13 and 14 days after transfer (30 and 31 days after onset).

3. Discussion

We encountered a case of COVID-19 in a patient who was taking iguratimod orally for rheumatoid arthritis. Previous reports have indicated that factors including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic respiratory diseases, and old age increase the severity of COVID-19, but data on rheumatoid arthritis and connective tissue diseases are scarce, and the risks are not clear [1]. The COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance has launched a patient registry currently collecting data to accumulate clinical knowledge on this group of patients [3].

Iguratimod is a conventional synthetic DMARD and is classified as an immunomodulator. No increased risks of morbidity or severity have been reported to date for diseases related to COVID-19, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), in patients taking the immunomodulatory DMARDs such as hydroxychloroquine and sulfa, gold preparations, and immunosuppressive DMARDs such as methotrexate, cyclosporin and azathioprine [[4], [5], [6]]. However, the Japanese College of Rheumatology recommends carefully considering reducing or even suspending treatment with DMARDs in cases of COVID-19 because, mechanistically, such drugs may aggravate the infection [7].

Overproduction of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-2, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α has been implicated in the deterioration of patients with COVID-19 [8,9]. In our case, though mild, we also observed an increase of soluble IL-2 receptor. Iguratimod suppresses the production of IL-6 and TNF-α [10]. Therefore, in this case, we were concerned that reducing iguratimod would cause the patient to deteriorate, so the same dose was continued, with a good clinical outcome. Administration of DMARDs, including iguratimod, to patients with COVID-19 needs further investigation.

Ciclesonide is an inhaled corticosteroid for the management of bronchial asthma, but it also possesses antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro [11]. In addition, there are limited evidences from case reports suggesting that ciclesonide inhibit proliferation of the virus and prevent progression to severe pneumonia when administered in the early or middle stages of infection [12]. In the present case, the patient took inhaled ciclesonide and her symptoms improved, although we cannot exclude the possibility that this would have been the natural course of the disease in this patient. In cases when it is difficult to synchronize drug spraying and inspiration as ciclesonide is administered using a pressurized metered-dose inhaler, the rate of drug arrival into the lungs may be reduced and may result in inadequate therapeutic efficacy [13]; however, in this case, the patient was able to inhale ciclesonide with guidance from nurses and without the use of an inhalation-assistive device.

Detection of viral RNA by real-time RT-PCR is used in most of the clinical studies, even though viral RNA presence cannot be strictly interpreted as infectious virus shedding [14,15]. The median duration of viral RNA positivity in nasopharynx of patients with COVID-19 is 17 days from onset (interquartile range, 13–22) [14]. However, in this case, PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 remained positive until 27 days after onset. Factors associated with prolonged detection of SARS-CoV-2 have been reported as male gender, old age, hypertension, steroid use, and severe symptoms [14], but it is unclear how the use of inhaled ciclesonide, iguratimod and other DMARDs affects viral shedding. The combination of DMARDs and steroids, however, is known to increase the risk of severe infection [16]. In our case, the patient's combined use of iguratimod and the steroidal agent ciclesonide might have contributed to prolonged viral presence. Thus, discontinuation of ciclesonide should be considered in COVID-19 patients receiving DMARDs soon after clinical symptoms have improved.

The patient was likely infected by her partner, who was positive for SARS-CoV-2, as she had no other close contacts. Yet she avoided contact with her partner after their onset of symptoms, which suggests she was infected during the incubation period. The potential for latent SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported, albeit minimally [17,18]. Thus, the possibility of infection during the incubation period may contribute to difficulties in controlling COVID-19, and caution is needed.

4. Conclusion

We have reported the case of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who suffered from COVID-19 while taking oral iguratimod. The patient who continued iguratimod therapy without dose reduction was treated with ciclesonide had an uneventful clinical course, but had prolonged viral RNA presence after resolution of symptoms. Further studies are needed to answer the many open questions on the administration of DMARDs during and after COVID-19, the therapeutic effect of ciclesonide on COVID-19, and the effect of DMARDs and ciclesonide on viral shedding.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Authorship statement: HB was the chief investigator and responsible for the data collection and analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Monti S., Balduzzi S., Delvino P., Bellis E., Quadrelli V.S., Montecucco C. Clinical course of COVID-19 in a series of patients with chronic arthritis treated with immunosuppressive targeted therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1036/annrheumdis-2020-217424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirato K., Naganori N., Harutaka K., Takayama I., Saito S., Kato F., et al. Development of genetic diagnostic method for novel coronavirus 2019 (nCoV-2019) in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson P.C., Yazdany J. The COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance: collecting data in a pandemic. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Antiga L. 2020. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients. The facts during the third epidemic. Liver transplantation: official publication of the American association for the study of liver diseases and the international liver transplantation society. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui D.S., Azhar E.I., Kim Y.J., Memish Z.A., Oh M.D., Zumla A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: risk factors and determinants of primary, household, and nosocomial transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:217–227. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacaille D., Guh D.P., Abrahamowicz M., Anis A.H., Esdaile J.M. Use of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1074–1081. doi: 10.1002/art.23913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japan College of Pheumatology Regarding novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) https://www.ryumachi-jp.com/information/medical/covid-19/

- 8.Pedersen S.F., Ho Y.C. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J Clin Invest. 2020 doi: 10.1172/JCI137647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J., Li S., Liu J., Liang B., Wang X., Wang H., et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.16.20023671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aikawa Y., Yamamoto M., Yamamoto T., Morimoto K., Tanaka K. An anti-rheumatic agent T-614 inhibits NF-kappaB activation in LPS- and TNF-alpha-stimulated THP-1 cells without interfering with IkappaBalpha degradation. Inflamm Res. 2002;51:188–194. doi: 10.1007/pl00000291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuyama S., Kawase M., Naganori N., Shirato K., Ujike M., Kamitani W., et al. The inhaled corticosteroid ciclesonide blocks coronavirus RNA replication by targeting viral NSP15. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.11.987016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwabuchi K., Yoshie K., Kurakami Y., Takahashi K., Kato Y., Morishima T. Therapeutic potential of ciclesonide inhalation for COVID-19 pneumonia: report of three cases. J Infect Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe T., Hattori T., Maeda K., Tukamoto S., Tobata H. Research and development of the inspiration timing evaluation system in the pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) Jpn J Med Instrum. 2014;84:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu K., Chen Y., Yuan J., Yi P., Ding C., Wu W., et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding in patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis – Offic Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y., Guo C., Tang L., Hong Z., Zhou J., Dong X., et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto A., Matsui T. Risk of serious infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Jpn J Clin Immunol. 2015;38:109–115. doi: 10.2177/jsci.38.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishiura H., Linton N.M., Akhmetzhanov A.R. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]