Abstract

As involvement of consumers/survivors in planning, delivery, and evaluation of services has increased, expectations of authentic and effective engagement, versus tokenism, have also risen. Different factors contribute to, or detract from, authentic engagement. Writing from mental health consumer/survivor and nursing positioning, respectively, we aim to redress the common problem of including only a narrow range of views and voices. This paper introduces a conceptual model that supports leaders in research, clinical, service, and policy roles to understand the necessity of engaging with a broader spectrum of consumer/survivor views and voices. The model draws on published consumer/survivor materials, making explicit diverse experiences of treatment and care and identifying the subsequent rich consumer/survivor advocacy agendas. We propose that strong co‐production is made possible by recognizing and welcoming consumer/survivor activist, facilitator, transformer, and humanizer contributions. The conceptual model forms the basis for a proposed qualitative validation project.

Keywords: consumer advocacy, co‐production, health policy, mental health services, patient participation, service users

Introduction

In the decades following deinstitutionalization of mental health services, there has been an increasing focus on including consumers/survivors in the planning, delivery, and evaluation of services (Evans et al. 2012). As involvement of consumers/survivors has increased, views about authentic and effective engagement have evolved. For example, in recent years, models of co‐design and co‐production (Gillard et al. 2010; Roper et al. 2018) have surfaced, and people are employed in increasing numbers and at higher levels of influence into what are typically called ‘consumer roles’. However, many barriers to effective consumer/survivor engagement exist and there is a disconnection between policy aspirations and practice on the ground (Happell et al. 2018; Pilgrim 2018).

Policies and research suggest there have been improvements in the practice of consumer/survivor engagement in services and government (Read & Maslin‐Prothero 2011; Wallcraft et al. 2011). However, many engagement processes remain tokenistic and ineffective (Craig 2008; Gee et al. 2016; Read & Maslin‐Prothero 2011). A variety of factors contributes to, or detracts from, authentic consumer/survivor engagement (Boaz et al. 2016). One of these factors, and the focus here, is a failure to intentionally engage with a more complete spectrum of consumer/survivor views and voices. In keeping with the spirit of co‐production, the authors have described this problem, writing from a consumer/survivor perspective and a nursing perspective, respectively. Both the current problems and the proposed model promoting improved engagement are considered for their relevance to nurses and consumers/survivors.

Consumer/survivor perspective

Indigo Daya has been an active consumer/survivor worker for fourteen years, working in senior roles across the mental health sector and government.

I have participated in many projects that recruit only a single consumer/survivor participant (yet recruit many clinicians). In these contexts, I wince when hearing a policymaker or clinician ask, ‘What do consumers think about…’? I wince because there is no way to answer that question without excluding the deeply held views of many people. When employed in a consumer role, is it my responsibility to share my own views, the ‘most common’ views, the views that are least often heard, or try to speak to all the different views I have heard? Another concerning practice is that of engaging only people who have positive things to say about services: ‘…some of us are picked because we are ‘tame’ and will ‘go along’ with whatever is said and done’ (Meagher 2011).

There can never be a single ‘representative’ consumer or survivor who can speak authentically to all our needs. Consumers/survivors, like any cross‐section of a population, are a heterogeneous group. In some policy circumstances, it is understood that our experiences vary in terms of demographics, identity, and culture, for example engaging with youth. However, independent of differences in demographics, identity, and culture, consumers/survivors also have differing experiences of mental health treatment and care. These experiences inform our views about what makes for a safe and helpful service. In practice, this means that engaging with just one consumer/survivor, or limiting engagement only with groups of people whose views are similar, can never result in an authentic, respectful, or effective engagement process.

There is a need to deepen our thinking about how best to accomplish authentic and effective engagement, beyond current practices, to involve more people, but most importantly, to think about which views and experiences are engaged with, in what contexts, and why.

Nursing perspective

A/Prof Bridget Hamilton is Director of the Centre for Psychiatric Nursing. She leads a programme of health services research undertaken with a team of Nursing and Consumer/Survivor Academics.

As a practicing nurse and academic, I invest in listening to people who have expertise that I myself lack; that is, the understanding developed through an experience of being a mental health consumer or survivor. Among my clinician colleagues, I often see a disconnection between the desire to include consumer/survivor views and the difficulty in then accepting what people have to say. Our engagement can be highly conditional on whether we clinicians, managers, researchers, and policymakers can bear to hear consumers/survivors on a given topic. As Indigo noted, one common solution to this impasse is to filter which person or persons to consult. Another solution is to filter out questions that may draw a challenging response. These conditional approaches perpetuate engagement that is ineffective or tokenistic. I see this played out in committees, in project work, and in reviews of written submissions.

An obvious point of difficulty for we clinicians is hearing about the impact of our decisions to invoke provisions in mental health law, to treat people without their consent. Yet, I find that even in such conflict‐ridden circumstances, consumers and survivors contribute varied and nuanced views and thinking that are invaluable to practice change. There is a tremendous opportunity to broaden out our field of engagement.

As both these first‐person accounts indicate, consumer engagement in our respective work domains sometimes reflects tokenism. Tokenism, defined as ‘The practice of making only a perfunctory or symbolic effort to do a particular thing, especially by recruiting a small number of people from under‐represented groups in order to give the appearance of [sexual or racial] equality within a workforce’ (Stevenson, 2011), contrasts with the goal we are pursuing through this work, to support engagement of diverse consumer/survivor voices.

Aim

Consumer engagement is an increasingly common practice in mental health settings, including consultation, participation, co‐design, and co‐production; however, little attention has been paid to the decision about which consumers to invite into these engagement practices and why.

This paper aims to improve practices of consumer/survivor engagement in mental health systems. In particular, we aim to influence more inclusive engagement processes that move away from tokenistic engagement and towards intentional engagement with greater numbers of diverse consumer/survivor views and voices.

A conceptual model is proposed which seeks to inform richer understandings about diverse and challenging consumer/survivor views. The model describes differing experiences, language preferences, and views about advocacy priorities that are held by consumers and survivors. The model is novel in seeking to understand an area about which there is a dearth of existing literature, that is, the relationships between people’s experience of treatment and care, and the views they hold.

In the future, we aim to explore the model’s fit to empirical data, in the form of published first‐person narratives.

Background

The international consumer/survivor movement has been grounded in the civil and human rights agendas of liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s due to the implications of mental health laws, particularly compulsory treatment. Judi Chamberlin, a seminal activist in the international psychiatric survivor movement, said in 2007:

We have a moral imperative to fight for justice….The day that they took my own freedom away was the day that I dedicated myself to this cause, I said ‘this is wrong, this is wrong, this should not happen to anyone’.(National Coalition of Mental Health Consumer/Survivor Organisations 2015)

Politically, Chamberlin and other activists saw that their fight for human rights, freedom, and justice was aligned with the struggles of other marginalized groups. Today, we see similar patterns as the consumer/survivor movement identifies its quest for self‐determination with a broader social agenda:

Like other marginalised and oppressed groups in society, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, women, LGBTIQ people, and people with disability, mental health consumers are increasingly saying that: We can speak for ourselves, and psychiatrists, nurses, organisations, and even family members, do not always know, or ask for, what we really want and need.(VMIAC 2019b)

Diverse consumer/survivor experiences, views, and voices

Unsurprisingly, people hold differing positions in relation to experiences of distress/mental ‘illness’ and of mental health services, and in how they speak about these. As well, the way people speak may be influenced by different contexts they are in, and may not be fixed, but fluid. A discursive framework has been proposed to understand the different ways people speak about their experiences of psychiatry, distress, and service use: patient, consumer, and survivor (Speed 2006). In this framework, the ‘patient discourse’ is typified by the person’s acceptance of diagnosis, the ‘survivor discourse’ resists or rejects diagnosis and the ‘consumer discourse’ neither fully accepts nor fully rejects diagnosis, being in a position of negotiation. It is important to note that these are discursive categories, rather than ways that people self‐identify.

There are many examples of diverse consumer/survivor voices and views. Antipsychiatry positions are voiced by survivors (Burstow 2017) and by critical voices inside the psychiatric profession (Moncrieff & Middleton 2015). Alternatives to biomedical mental health treatments are growing, with the Hearing Voices Movement (Corstens et al. 2014), peer support, and consumer/survivor‐run services (Grey & O’Hagan 2016; Rose et al. 2016). The Internet and social media have enabled consumers/survivors to connect with each other in creative and impactful ways, as seen in the Icarus Project (DuBrul 2014), organizations like VMIAC (VMIAC 2019) and the National Empowerment Center (National Empowerment Center 2019), and a proliferation of blogs and social media forums run by consumers and survivors. Mad Studies has joined the curriculum at UK and Canadian universities as an emergent academic discipline led by consumers/survivors (Faulkner 2017).

However, consumer/survivor voices can and do contradict each other. For instance, many consumers promote recovery‐oriented approaches, such as the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) developed by consumer Mary Ellen Copeland (Pratt et al. 2013). At the same time, the survivor‐run Recovery in the Bin collective (RITB 2019) is stridently critical of co‐opting recovery orientation.

Another prominent voice is that of people expressing positive experiences of psychiatric services. These voices are less commonly raised via organized activism, perhaps because there is less motivation for collective action among people who are satisfied with a system, but they are often heard as human‐interest elements of media reports on mental illness (The Project 2018, May 28) and are aligned with Speed’s ‘patient discourse’. This paper contends that none of these voices are more or less true or valuable than others, and they should all be welcomed.

While there are many examples of diverse consumer/survivor views in public narratives, mental health systems do not always make space to hear these voices. Whole swathes of views are de‐legitimized in mental health, for example, that people can recover from psychosis without neuroleptic medication, or that inpatient admissions may sometimes be more harmful than helpful. Yet in practice, mental health clinicians and researchers know well that the efficacy of treatments varies greatly (Lally & MacCabe 2015; Leucht et al. 2017), as does the experience of unwanted treatment effects (Read & Williams 2019; Solmi et al. 2017). Further, it is well known that mental and emotional experiences, and experiences of care, can vary significantly. It is no surprise then that different experiences will lead to different views, and some of these will be critical.

The model: overview

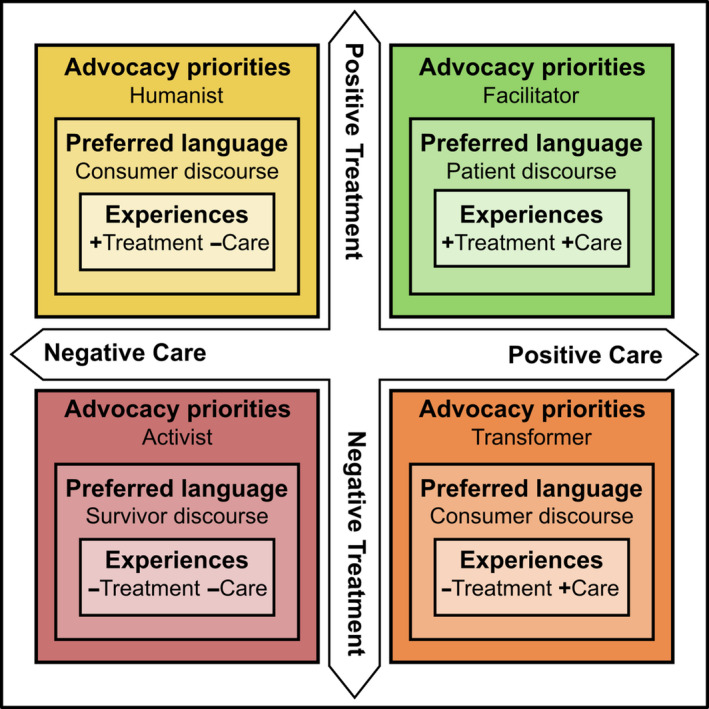

The conceptual model proposed in this paper describes four categories of diverse consumer/survivor experiences, voices, and views which may not otherwise be evident to people working in mental health policy, research, and practice.

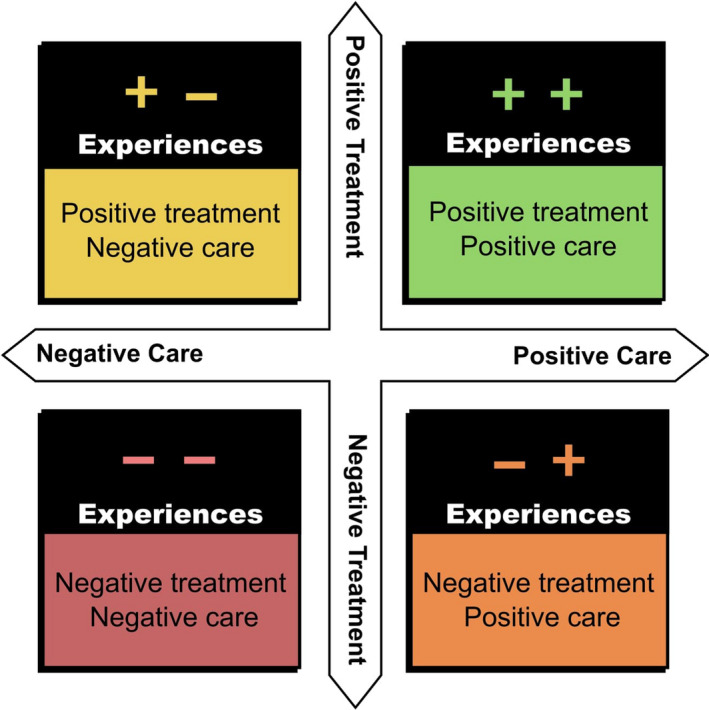

Underpinning the model is the hypothesis that views are influenced by experiences, and further that consumer/survivor experiences of treatment are distinct from experiences of care. This hypothesis is illustrated in the model by separate axes for treatment and care experiences; these axes intersect to form a matrix with four quadrants. The model is progressively expanded in the following sections to describe and illustrate, for each of the four quadrants: diverse experiences (Figs 2 and 5), language preferences (Fig. 6), and advocacy priorities (Fig. 7). Figure 1 illustrates an integrated version of the model.

Figure 2.

Diverse experiences in the model.

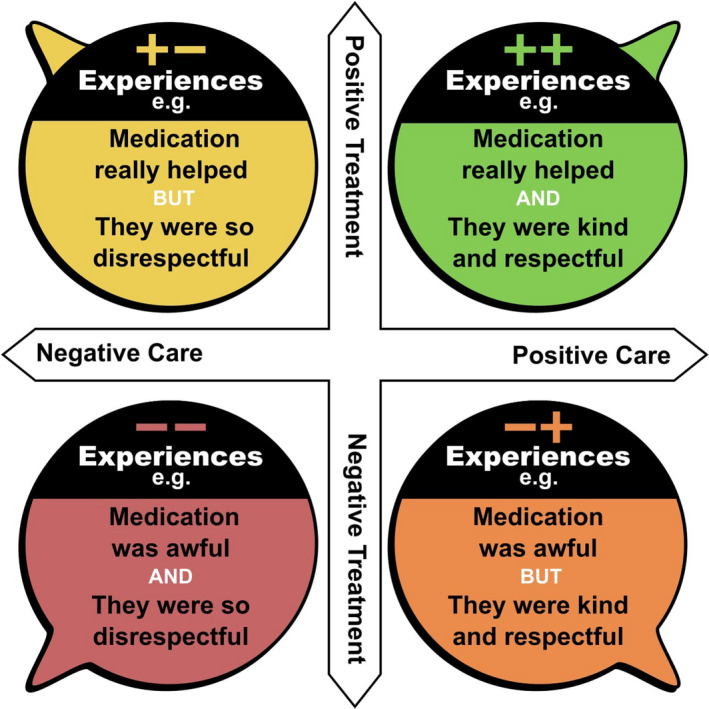

Figure 5.

Examples of diverse experiences in the model.

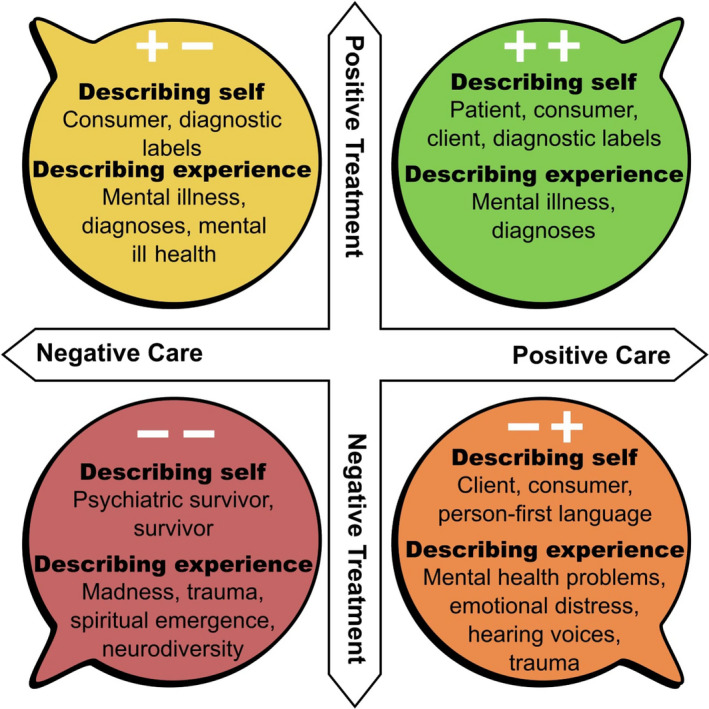

Figure 6.

Examples of diverse preferred language in the model.

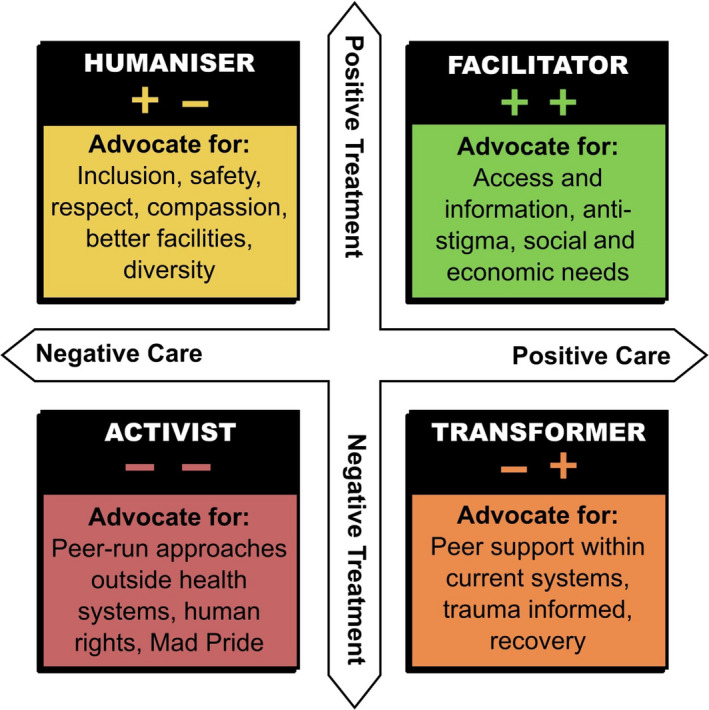

Figure 7.

Examples of advocacy priorities in the model.

Figure 1.

Integrated model: Experiences, preferred language, and advocacy priorities.

The model is informed by Speed’s categories of patient, survivor, and consumer discourses (2006), but it adds new dimensions. First, the model differentiates between experiences of treatment and care, generating four categories rather than Speed’s three categories. Second, the model examines how people’s experiences of mental health services connect with language preferences and priorities for change.

The four categories of diverse consumer/survivor views are not intended to define identities, or groups of actual people: the model depicts diverse views rather than people. In practice, experiences, preferred language, and advocacy priorities will rarely line up as neatly as this model suggests, and diversity of language use and advocacy priorities may cross over between groups. Individuals may have mixed experiences, change their views over time, or express different views depending on the setting. However, the model proposes that these broad groupings represent four relevant and common sets of views. Each of these four views can provide critically important insights for practitioners, researchers, quality managers, and policy advisers.

The model: different experiences

The model shown in Figure 2 illustrates two important axes of consumer/survivor experiences in mental health services – treatment and care – and plots different experiences on each axis.

It is our observation that consumers/survivors often distinguish between these two types of experience. ‘Care’ here encompasses the overarching elements of contact and interaction with people and environments, as part of a person’s encounter with a mental health service. For the purposes of this paper, ‘treatment’ is understood to be diagnosis‐related treatment within those services, most commonly pharmacological treatment. Treatment also encompasses ECT and other formalized treatments.

Experience of treatment axis

Consumer/survivor experiences of mental health treatment can be viewed along a continuum, shown in Figure 3. This axis describes the overall experience of the effectiveness of treatment, as determined by the person. In its most simplistic form, this axis describes whether a person experienced treatment as helpful (positive) or harmful (negative).

Figure 3.

Treatment axis.

Positive experience is defined as treatment which has an effect that is valued by the person.

Examples of positive treatment experiences are people who find that a psychiatric diagnosis provided a meaningful and affirming explanation of their experience, or people who find medication or electroconvulsive therapy beneficial, aligning with Speed’s (2006) ‘patient’ discourse.

My reaction, both to my initial depression diagnosis and later bipolar diagnosis, was one of complete relief. It was such a relief to understand why I was feeling the way I was feeling…. (Jacqui n.d..)

ECT was something I decided in partnership with my treating team. I had to trust them because I was desperate for relief and too unwell to be confident in my own treatment decisions. It wasn’t barbaric, or something that I didn’t have a choice about. I feel thankful that when nothing else worked, it got me through. (Karen 2017)

In contrast, experiences of negative treatment might include people who find diagnostic labels disempowering or disrespectful, or who find medication or electroconvulsive therapy makes them feel worse. Applying Speed’s analysis, these experiences may align with ‘rejecting’ or ‘resisting’ mainstream mental health services (survivor discourse).

I entered the hospital as Robert Bjorklund, an individual, but left the hospital 3 weeks later as a ‘schizophrenic’. (Forgione 2019)

I was transformed from a twenty‐eight‐year‐old, happy, optimistic, musical woman to a person who could not think or feel. My capacity to be myself was severely diminished. Electroshock damaged my brain and made it very difficult to be a first‐time mother to my newborn daughter. I do not remember holding her in my arms for the first time. We were separated until June. My heart was broken.(Maddock 2014)

These examples from lived experience narratives illustrate profoundly different views between consumers/survivors about the experience of receiving a diagnosis or undergoing electroconvulsive therapy. Differences can be found in many other consumer/survivor narratives about treatment experiences.

Experience of care axis

In this model, the experience of care axis (see Fig. 4) includes people’s opinions about the service context within which treatment was provided. This includes the physical environment, the attitudes, skills and knowledge of staff, the quality of relationships with staff, experiences relating to human rights and statutory or coercive actions, being free from violence and abuse, and experiences that impact dignity and respect.

Figure 4.

Care axis.

Examples of negative care experiences can range from feeling unsafe to experiencing violence and abuse.

I always felt uncomfortable in these mixed wards, especially when I was locked in. On this admission I was stalked by a male patient. He threatened me several times. I reported him but the staff did nothing to make me feel safe. I’m not even sure if they believed me. (Jeffs 2009, p.186)

I needed help, but instead I was treated like a disobedient child with a broken brain, punished and controlled, including more than two months in a locked unit. I went from being a human being to being a mental patient. I was put in restraints – not because anything I did but they said it was just for transporting me to the hospital. After being restrained I had nightmares that I was being raped, and I still have flashback reactions to anything that reminds me of that experience.(Hall n.d.)

Examples of positive care experiences can include things like feeling heard, respected, and cared for:

My case manager and I built a good, trusting relationship so I talked about experiencing sexual abuse when I was about 6, which I’d never talked about before. It felt like a huge relief to get it off my chest and let someone know how it affected me. (Nathan n.d.)

But there was this one bloke and he was terrific. Somehow he could manage to work out his time with the clients that he had to look after and he would talk to them. He would go out, he would sit with them and he would talk to them and he seemed to do it with each client he had ….and it was so important and that was probably the biggest thing you could get because that is what we are asking for. We need someone to listen.(Roper 2003)

These examples illustrate divergent consumer/survivor experiences along the model’s axis of care, including diverse experiences of relationships with staff, and whether or not people felt heard, respected, and safe.

The first author, in reflecting on the array of care experiences that she has heard from consumers/survivors over many years, developed Table 1 which outlines some indicative factors which appear to impact on experiences of care.

Table 1.

Illustration of factors impacting care experiences

| Experiences of safe, respectful care | Experiences of hurtful, disrespectful care |

|---|---|

|

|

Some simple examples of these differing kinds of treatment and care experiences are used in Figure 5 to populate the model.

The model: views about preferred language

The model suggests that people’s experiences of treatment and care can influence different language preferences for describing personal experiences of distress/mental ‘illness’ and describing oneself in relation to that experience.

Positive treatment experiences: When people experience treatment as helpful, they may be more likely to accept and even embrace the clinical concepts and language used in services (patient discourse)

Describing self: Patient, person with mental illness, own diagnostic labels, for example ‘I have schizophrenia’

Describing mental health experience: Mental illness, mental ill health, bipolar disorder, and hallucinations.

Negative treatment experiences: People from these groups experience treatment as harmful, and so they may be more likely to describe themselves and their experiences in ways that deliberately contrast with clinical terminology, such as:

Describing self: Psychiatric survivor, trauma survivor, and neuro‐diverse

Describing mental health experience: Madness, emotional problems, crisis, trauma, spiritual emergence, and hearing voices (survivor discourse).

In addition to these views and language use, positive or negative experiences of care also influence views and language in relation to self and systems.

Negative care experiences: People with these experiences are more likely to describe needs in terms of human rights and safety issues, and people may reject the identity of consumer (survivor discourse). The experience may motivate people to explore and describe alternative conceptual frames, environments, or systems.

Positive care experiences: People in these groups are more likely to adopt the terms client or consumer, voice greater trust in the people and systems, and explore enhancement within the frame of current service systems (patient or consumer discourse).

When the two axes of treatment and care interact, granularity of meaning emerges in preferred language use, as shown in Figure 6.

Negative treatment and care experiences tend to involve language that positions people and experiences outside of language used by health systems. These language variations are not simply a matter of personal preference, but can be deeply meaningful, and may be linked to both personal meaning frameworks and to the consumer/survivor movement history. For example, the term neurodiversity, while more commonly used, but still contested, in the autism disability rights movement (Saunders 2018), is used by some psychiatric survivors to signify that the person values their experiences as something positive, in contrast to others who may find mental health experiences distressing.

Words like ‘disorder,’ ‘disease,’ and ‘dysfunction’ just seem so very hollow and crude. I feel like I’m speaking a foreign and clinical language that is useful for navigating my way through the current system but doesn’t translate into my own internal vocabulary, where things are so much more fluid and complex….(DuBrul 2014)

The model helps to identify and value opinions from consumers/survivors whose awareness and motivation might arise from negative treatment and/or care experiences. It places these alongside the more palatable, affirming views others can bring to processes of engagement.

The model: views about advocacy priorities

Finally, the model can help to characterize advocacy issues that tend be prioritized by people with similar experiences and views, as shown in Figure 7. In this version of the model, each category in the model is provided with a descriptive label that attempts to characterize advocacy aims. These descriptive labels include facilitators, humanizers, transformers, and activists.

Activists

This group may include people with negative experiences of treatment and care, who may describe themselves as ‘psychiatric survivors’, and their experiences as madness, neurodiversity, spiritual emergence, hearing voices, or trauma. Activists may be more likely to advocate for radical reform, for the abolition of psychiatric services, for peer‐run services outside of health systems, for social movements like ‘Mad Pride’, and to be highly critical of human rights inequities and harms within psychiatric services.

Health services and health professionals may be most challenged by views from this activist position, though these experiences are just as valid as those from the other groups. This politically vocal group of survivors sometimes has less opportunity to speak, yet to exclude these voices from opportunities to engage with improvement and reform processes may result in missing out on the most innovative contributions.

Facilitators

This grouping features people with positive experiences of treatment and care, who may be at ease with diagnostic labels, and medical descriptions of their own experiences. Facilitators may be more likely to advocate for expansion of services, for better access to existing services, and for information about mental illness and how to get ‘help’.

Facilitators are most readily engaged as insiders to services and frequently invited into consumer engagement opportunities. They are more likely to nuance and support incremental improvement, rather than to challenge existing power balances or practice approaches, or to lead innovation.

Humanizers

With the mixture of positive experience of treatment but a negative experience of care, the interests of this group may lie in a humanitarian lens applied to processes and systems. Advocacy priorities for humanizers may include improving the culture of services, the quality of facilities, and the attitudes of staff. They may also focus on particular diversity needs related to identity, culture, or demographics, such as gender safety, access to language interpreters, or age‐appropriate services.

Transformers

This group has a mixed experience including negative treatment experiences but positive care experiences. Transformers may be more likely to advocate for significant reforms underpinning models and alternative knowledge frameworks and therapies within current health systems. This includes a focus on recovery‐oriented services, trauma‐informed services, championing peer support, or hearing voices approaches within existing services.

Discussion

This model provides a different approach to the conceptualization of authentic engagement. First, by mapping the high variability of consumer/survivor experiences, the model explains why engaging with only a single consumer or survivor as ‘representative’ is tokenistic and futile (Bennetts et al. 2013; Happell & Roper 2006). Second, the model is progressively expanded to suggest that different experiences of treatment and care may shape people’s preferred language about those experiences. Third, the model suggests that these different experiences may influence people’s views about advocacy priorities. Descriptive labels – activists, transformers, humanizers and facilitators – are provided for each group of differing consumer/survivor voices, arising from experiences, language preferences, and advocacy priorities.

Further, the model challenges the idea that a thorough picture of diverse consumer/survivor experiences can be gained by simply seeking the views of people with varying demographics, identity, and/or cultural experiences. This is not to suggest that these characteristics are not relevant: in fact, they may well be important mediators in how people experience treatment and care (Buettgen et al. 2018). However, even these more inclusive approaches run the risk of tokenistic engagement if they oversimplify the complexities of individual experiences.

By focusing on different experiences of treatment and care, the model provides a pragmatic evolution in thinking about who could be engaged and why.

Relevance of the model for practice and policy

At a high policy level, there is too much at stake to allow only selected voices to shape policy and reforms (Wallcraft et al. 2011). The model has value for consultative processes, by describing a diversely representative and rich group of consumer/survivor views with which policy questions and proposed initiatives should be tested. For researchers, policy, and practice leaders seeking to engage or coproduce with consumers/survivors, the model provides guidance for thinking about who to engage with. The model prompts researchers, policy, and practice leaders to:

Broaden understandings of diversity to include different experiences of care and treatment

Apply critical reasoning to the selection of consumers/survivors who are engaged

Consider using positive and negative experiences of treatment and care as defining characteristics for inclusive engagement

Connect with more consumers/survivors

Respectfully respond to the diversity of consumer/survivor language preferences

Develop an awareness of, and counteract potential bias in, themselves and systems, then to seek out consumers/survivors with opinions that are challenging to hear.

For consumer/survivor advocates, the model prompts considerations of ethical and inclusive lived experience practice. Lived experience roles are still emergent, with relatively little literature or structures guiding practice standards (Davidson 2015) or ‘articulated, agreed ideas of what lived experience work is and what informs it’ (Byrne et al. 2018), particularly for consumer consultants and consumer advisers. In this context of little guidance, it is not surprising if some consumer/survivor workers speak primarily from their own personal view – potentially without an awareness that other views, voices, and opinions might exist. The model creates opportunities for consumer/survivor workers to:

Understand their own experience, view, and voice relative to others

Learn about other consumer/survivor positions

Welcome and work alongside consumers/survivors with positions from all quadrants of the model

Conceptualize language use which is inclusive of diverse experiences and preferences

Advocate for changes which respect and address the needs of people from all quadrants of the model.

Limitations

The model depicts a simplifed ideal, and of course consumer/survivor experiences and opinions are more complex than depicted. People’s views and voices may be influenced by more factors than the two axes described. Some other influences may include the variety of mental health services used (type of services, accessibility of services), impact of addiction and disability, changes in experience and opinion over time, and experiences of mental health problems (e.g. valued versus distressing, meaningful versus meaningless), alongside the more well‐understood impacts of identity, demographics, and culture. Further research into these and other factors that impact consumer/survivor positions may, over time, provide a more comprehensive model.

Given that treatment and care experiences have been discussed with a focus on the poles of two axes, it is also likely that further groupings may emerge towards the centre of these axes, perhaps arising from ambiguous or mixed experiences.

The authors also note the potential problems with introducing these categories and labels, when categories and labels are a high priority concern for many consumers and survivors. We reaffirm that the categories in the model should not be used to describe identities or groups of actual people, but rather as a guide to seek out and welcome more diverse experiences and views.

Conclusions

The conceptual model promotes a considered and comprehensive approach to authentic engagement of consumers/survivors in mental health, and health systems more generally. Consumers/survivors predictably have diverse experiences in relation to treatment and care. These are organized into a spectrum of differing consumer/survivor views about language use, personal experiences, and positions on advocacy agendas. The model is a resource for those at the leading edge in research, services, and policy environments, to assist in more authentic, equitable, and effective engagement practices.

Acknowledgements

A research project is currently underway by the authors to validate the conceptual model described in this paper, via qualitative analysis of publicly available consumer/survivor narratives. This research is funded by a Community Fellowship Grant from the Melbourne Social Equity Institute at the University of Melbourne, with support from the Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council (VMIAC). The Centre for Psychiatric Nursing, University of Melbourne, is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services.

Authorship statement: All authors listed have made substantial contributions to the conceptualization, writing, and review of this manuscript, and meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical journal Editors. All authors are in agreement with the manuscript.

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the production of this paper.

References

- Bennetts, W. , Pinches, A. , Paluch, T. & Fossey, E. (2013). Real lives, real jobs: Sustaining consumer perspective work in the mental health sector. Advances in Mental Health, 11, 313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Boaz, A. , Biri, D. & McKevitt, C. (2016). Rethinking the relationship between science and society: Has there been a shift in attitudes to Patient and Public Involvement and Public Engagement in Science in the United Kingdom? Health Expectations, 19, 592–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettgen, A. , Hardie, S. , Wicklund, E. , Jean‐François, K. M. & Alimi, S. (2018). Understanding the Intersectional Forms of Discrimination Impacting Persons with Disabilities Ottowa: Canadian Centre on Disability Studies. Available at: http://www.disabilitystudies.ca/projects--intersectional-forms-of-discrimination.html.

- Burstow, B. (2017). Antipsychiatry. Say what?. Mad in America, 15 June. Available at: https://www.madinamerica.com/2017/06/antipsychiatry-say-what/.

- Byrne, L. , Stratford, A. & Davidson, L. (2018). The Global need for lived experience leadership. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41, 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corstens, D. , Longden, E. , McCarthy‐Jones, S. , Waddingham, R. & Thomas, N. (2014). Emerging perspectives from the hearing voices movement: Implications for research and practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 40, S285–S294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, G. (2008). Involving users in developing health services. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 336, 286–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, L. (2015). Peer support: Coming of age of and/or miles to go before we sleep? An introduction. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42, 96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBrul, S. A. (2014). The Icarus project: A counter narrative for psychic diversity. Journal of Medical Humanities, 35, 257–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. , Rose, D. , Flach, C. , et al. (2012). VOICE: Developing a new measure of service users' perceptions of inpatient care, using a participatory methodology. Journal of Mental Health, 21, 57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, A. (2017). Survivor research and Mad Studies: The role and value of experiential knowledge in mental health research. Disability & Society, 32, 500–520. [Google Scholar]

- Forgione, F. A. (2019). Diagnostic dissent: Experiences of perceived misdiagnosis and stigma in persons diagnosed with schizophrenia. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 59, 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, A. , McGarty, C. & Banfield, M. (2016). Barriers to genuine consumer and carer participation from the perspectives of Australian systemic mental health advocates. Journal of Mental Health, 25, 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillard, S. , Turner, K. , Lovell, K. , et al. (2010). 'Staying native': Coproduction in mental health services research. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23, 567–577. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, F. & O’Hagan, M. (2016). The effectiveness of services led or run by consumers in mental health: rapid review of evidence for recovery‐oriented outcomes Sax Institute. Available at: https://nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/resources/the-effectiveness-of-services-led-or-run-by-consumers-in-mental-health-rapid-review-of.

- Hall, W. (n.d.). Will Hall’s Recovery Story. National Empowerment Center Recovery Stories. Available at: https://power2u.org/will-halls-recovery-story/.

- Happell, B. & Roper, C. (2006). The myth of representation: The case for consumer leadership. Australian e‐Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 5, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Happell, B. , Scholz, B. , Gordon, S. , et al. (2018). 'I don't think we've quite got there yet': The experience of allyship for mental health consumer researchers. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25, 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacqui . (n.d.). Personal Stories. The Black Dog Institute. Available at: https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/personal-stories/jacqui.

- Jeffs, S. (2009). Flying With Paper Wings: Reflections on Living with Madness. Victoria: The Vulgar Press, p.186. [Google Scholar]

- Karen . (2017). Karen's Story. Mental Health Commission of NSW, Stories. Available at: https://nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/resources/stories/karens-story-0.

- Lally, J. & MacCabe, J. H. (2015). Antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: a review. British Medical Bulletin, 114, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht, S. , Leucht, C. , Huhn, M. , et al. (2017). Sixty years of placebo‐controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, bayesian meta‐analysis, and meta‐regression of efficacy predictors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 927–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddock, M. (2014). Electroshock Causes More Harm Than Good. Mad in America, 9 May. Available at: https://www.madinamerica.com/2014/05/electroshock-causes-harm-good/.

- Meagher, J. (2011). Changing perspectives on consumer involvement in mental health. Health Voices ‐ Journal of the Consumers Health Forum of Australia, 8, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moncrieff, J. & Middleton, H. (2015). Schizophrenia: A critical psychiatry perspective. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 26, 264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan . (n.d.). Nathan's Story. Orygen Youth Health. Available at: https://oyh.org.au/client-hub/client-stories/nathans-story. [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition of Mental Health Consumer/Survivor Organisations (2015). Judi Chamberlin: Her life, our movement. Available at: https://www.ncmhr.org/Script-JudiVideo.htm.

- National Empowerment Center (2019). Programs and services. Available at: https://power2u.org/what/.

- Pilgrim, D. (2018). Co‐production and involuntary psychiatric settings. Mental Health Review Journal, 23, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, R. , MacGregor, A. , Reid, S. & Given, L. (2013). Experience of wellness recovery action planning in self‐help and mutual support groups for people with lived experience of mental health difficulties. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read, S. & Maslin‐Prothero, S. (2011). The involvement of users and carers in health and social research: The realities of inclusion and engagement. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 704–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read, J. & Williams, J. (2019). Positive and negative effects of antipsychotic medication: An international online survey of 832 recipients. Current Drug Safety, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RITB (2019). Recovery in the bin: A critical theorist and activist collective. Available at: https://recoveryinthebin.org/.

- Roper, C. (2003). Sight Unseen: Conversations Between Service Receivers: On Mental Health Nursing and the Psychiatric Service System. Melbourne: Centre for Psychiatric Nursing Research and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, C. , Grey, F. & Cadogan, E. (2018). Co‐production ‐ Putting principles into practice in mental health contexts. Available at: https://recoverylibrary.unimelb.edu.au/domains/leadership.

- Rose, D. , MacDonald, D. , Wilson, A. , Crawford, M. , Barnes, M. & Omeni, E. (2016). Service user led organisations in mental health today. Journal of Mental Health, 25, 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, P. (2018). Examining competing discourses of autism advocacy in the public sphere. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Solmi, M. , Murru, A. , Pacchiarotti, I. , et al. (2017). Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first‐ and second‐generation antipsychotics: a state‐of‐the‐art clinical review. Therapeutics & Clinical Risk Management, 13, 757–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed, E. (2006). Patients, consumers and survivors: A case study of mental health service user discourses. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, A. (2011) Oxford dictionary of English. [electronic resource]. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://search-ebscohost-com.ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00006a&AN=melb.b5231678&site=eds-live&scope=site (Accessed: 9 July 2019).

- The Project . (2018). Shock therapy. [Facebook status update]. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/TheProjectTV/videos/10155558199378441/?v=10155558199378441.

- VMIAC , (2019). Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council Campaigns. Available at: https://www.vmiac.org.au/campaigns/.

- VMIAC (2019b). Royal Commission into Mental Health: Terms of Reference Consultation Submission. Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council. Available at: https://www.vmiac.org.au/blog/royal-commission-update-3/.

- Wallcraft, J. , Amering, M. , Freidin, J. , et al. (2011). Partnerships for better mental health worldwide: WPA recommendations on best practices in working with service users and family carers. World Psychiatry, 10, 229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]