Abstract

Aim

To analyse the relationship between Spanish nurses’ intention to migrate and job security.

Background

Nursing emigration from Spain increased dramatically between 2010 and 2013. By 2015, emigration had returned to 2010 levels.

Methods

Single embedded case study. We examined publicly available statistics to test for a relationship between job security and applications by Spanish nurses to have credentials recognized for emigration purposes.

Results

Between 2010 and 2015, job security worsened, with poor access to the profession for new graduates, increased rate of professional dropout, increased nursing jobseekers and falling numbers of permanent contracts.

Conclusions

The number of accreditation applications in Spain in 2010 and 2015 was very similar, but job security worsened on a number of fronts. The distribution of work through part‐time contracts aided retention.

Implications for nursing management

Policymakers and health care administrators can benefit from understanding the relationship between mobility, workforce planning and the availability of full‐time, part‐time and short‐term contract work in order to design nursing retention programmes and ensure the sustainability of the health care system.

Keywords: emigration and immigration, job security, nurses, precarious work, Spain, statistical indicators, workforce

1. INTRODUCTION

The migration of health professionals has a long history (Nelson, 2013). Europe has seen an increase in migration among health professionals, which can be traced to the global financial crisis that began in 2008 and to EU expansion (OECD, 2015). In a recent study, we showed that nursing emigration from Spain is linked to job security (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016, 2018). Between 2009 and 2014, job security worsened due to the decrease in public spending, labour market reforms and the transformation of the health system, which all took place in reaction to the economic crisis (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016).

We follow other scholars in positing that labour markets drive migration through the supply and demand of employment and working conditions in different countries (Massey et al., 1993; O'Reilly, 2015; Wickramasinghe & Wimalaratana, 2016). In general, health professionals who emigrate are motivated by the opportunity for better salaries and quality of life, and their movement is usually from poor countries to rich ones (Salami, Nelson, Hawthorne, Muntaner, & McGillis Hall, 2014; for the Spanish case, see Gea‐Caballero et al., 2019). Other research in this line has found that one factor driving the migration of health professionals is the worldwide scarcity of health professionals (Buchan, 2015).

In this article, we examine the relationship between job security in nursing and the intention of nurses to emigrate from Spain between 2010 and 2015, using monthly employment indicators and the number of nurses applying to have their credentials validated for work in the EU (as a proxy for migration).

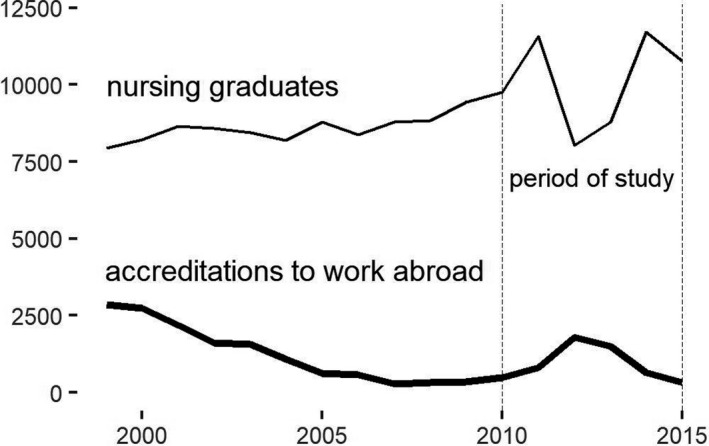

1.1. The financial crisis

Nursing emigration from Spain began in the 1990s (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2018) and increased greatly between 2010 and 2013, after the financial crisis (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016). Later, nursing emigration decreased, dropping by 2015 to levels at or below those of 2010 (Ministry of Education, Culture, & Sport [MECD], 2018). There is no official count of the number of nurses emigrating from Spain. We approximated this number using the number of nursing graduates who applied to have their studies accredited for work in the EU (“accreditation applications”) as shown in Figure 1 (Nursing graduates and applications for accreditation stating that a qualification or award obtained in Spain is regulated under Directive 2005/36/EC for work inside the EU). Although accreditation applications express the intention to emigrate and not actual emigrations, they can give us a sense of emigration trends.

Figure 1.

Number of graduates and number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad in Spain

The crisis led the Spanish government to apply austerity measures (Caravaca, González‐Romero, & López, 2017), which negatively affected the well‐being of the population and the quality of care (Cervero‐Liceras, McKee, & Legido‐Quigley, 2015) as well as the working conditions of health professionals (Granero‐Lazaro, Blanch‐Ribas, Roldán‐Merino, Torralbas‐Ortega, & Escayola‐Maranges, 2017). In 2013, for the first time in Spain's history, the number of active nurses dropped, falling by 5,200 nurses from the preceding year. Unemployment and temporary contracts increased, especially during the summer months, threatening job security (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016).

1.2. Nursing unemployment among spanish‐trained nurses

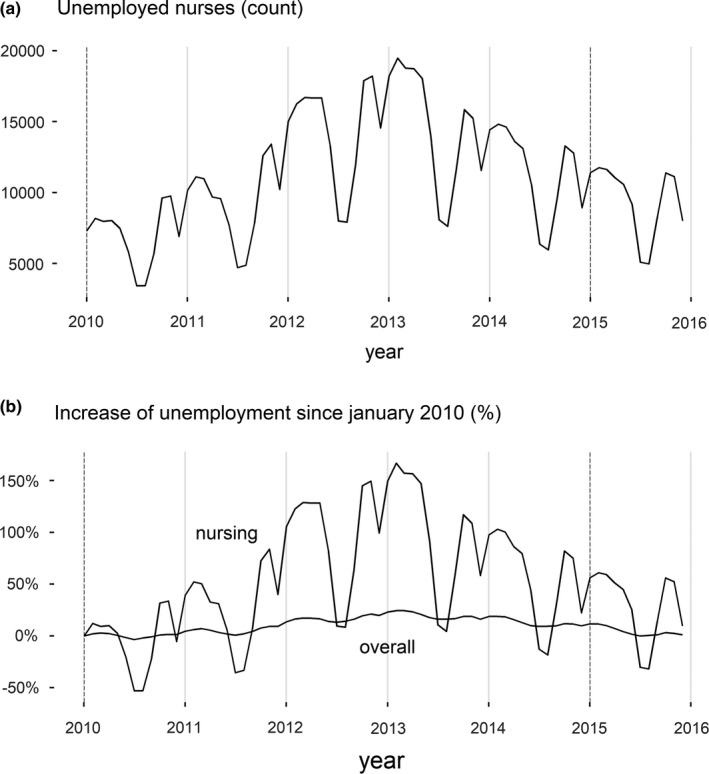

We analysed data from Spain's Public Service for State Employment (SEPE) of the Ministry of Employment and Social Security (MESS) between 2010 and 2015 (MESS, 2018). These data allow us to observe that nursing unemployment followed the same pattern as overall unemployment in Spain (Figure 2). Figure 2a shows the number of unemployed nurses (when they register with the SEPE, jobseekers list up to six occupations in order of preference. Unemployed nurses are defined as unemployed jobseekers who list nursing as their first choice). Figure 2b compares the variation in the percentage of unemployed nurses with the variation in the percentage of unemployed people for all occupations in Spain between January 2010 and December 2015, taking the values from January 2010 as a starting point. This figure allows us to see that both nursing unemployment and overall unemployment were seasonal and followed the same phase pattern. However, seasonal variation was much more pronounced in nursing, showing a much higher increase in the percentage of unemployed nurses than in overall unemployment.

Figure 2.

Nursing unemployment compared to overall unemployment in Spain

1.3. The lack of nursing job security

Job security, which is threatened by both unemployment and casual employment, is linked to the emigration of Spanish nurses (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016; Gea‐Caballero et al., 2019). One element that undermines job security is “precarious work,” defined as work that is uncertain, unstable and insecure from the workers’ point of view (Kalleberg, 2009). Precarious work is associated with low‐quality employment (Burchell, Sehnbruch, Piasna, & Agloni, 2014) and described with terms such as flexible, informal, atypical, temporary, part‐time and casual (Benach et al., 2014). In addition, precarious work has social consequences affecting health inequalities (Benach et al., 2015), and precarious workers are in danger of being excluded from the labour market (Fernández, 2014).

In Spain, threats to job security have decreased nurses’ quality of life (Baranda, 2017; Granero‐Lazaro et al., 2017; 2017, & Martinez, 2017), which in turn causes them to feel uncertain about the future (Abades et al., 2017) and provokes job dissatisfaction (Girbau, Galimany, & Garrido, 2012). This dissatisfaction stems from the hostile work environment that can emerge from burnout (Muñoz et al., 2017) and from colleagues’ decision to drop out of the profession (Girbau et al., 2012).

Given our finding that the lack of job security is linked to nursing emigration from Spain (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016), in this study we broke down job security into a series of indicators: (a) the number of unemployed nurses without previous employment, (b) the proportion of registered jobseekers in nursing who list nursing as their first choice (as opposed to other fields) and (c) the quality of contracts measured in length (permanent or temporary) and time commitment (full‐time or part‐time). We chose these indicators because they allow us to focus on the largest group of nursing emigrants in Spain: young people with no professional experience (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016). We tracked these indicators over time in relationship to the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad (as a proxy for the number of migrant nurses).

We analysed the period between 2010 and 2015, which witnessed a marked increase and decrease in the number of Spanish nurses applying for accreditation. Between 2010 and 2012, the number of accreditation applications quadrupled. Then, between 2012 and 2015, the number fell to one fifth of the 2015 figure (Figure 1).

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

This is a single embedded case study (Yin, 2018). We developed four hypotheses with the goal of determining the relationship between job security and accreditation applications. We then tested our hypotheses using publicly available statistics on nursing employment. There are no direct statistics on the emigration of nurses from Spain. Therefore, we measured the emigration indirectly, using the number of applications for accreditation to work as a nurse in the EU, as an indicator of the intention to migrate.

We hypothesized that between 2010 and 2015:

The variation in the number and percentage of unemployed nurses without previous employment is related to the variation in the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad.

The variation in the percentage of nursing graduates that sought employment in nursing is related to the variation in the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad.

The variation in the quality of contracts, measured by their length and time commitment, is related to the variation in the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad.

Keeping in mind that the number of accreditation applications in 2010 and 2015 is very similar, the indicators of job security will also be similar for these two years.

2.2. Participants

The study population was Spanish‐trained nurses as represented in publicly available statistics. We used the terms “non‐specialized nurses” and “specialized nurses except for midwives” from the SEPE. The MECD term “unemployed nurses” refers to those without work and registered as seeking employment. We used the term “nursing graduate,” as defined by the MECD, to describe those who have obtained a recognized qualification in nursing in a given year.

Due to political changes in 2018, the ministries have changed their names. Currently, they are Ministry of Labour, Migrations and Social Security and Ministry of Education and Professional Training.

2.3. Data collection

We obtained the data from the SEPE's monthly reports between 2010 and 2015 and from the MECD.

2.4. Ethical considerations

Because we used publicly available statistics, no consent process was necessary.

2.5. Data analysis

We plotted the temporal series of the statistical indicators published by the SEPE and the MESS. We evaluated each of the hypotheses by comparing patterns in accreditation applications with patterns in the four indicators. We used the data visualization package ggplot2 of the R statistical computing environment (R Core Team, 2018).

2.6. Validity, reliability and rigour

We triangulated data from several sources. To test hypotheses 1, 2 and 3, we used data from the SEPE (Figures 3 and 5). To test hypothesis 4, we additionally used data from the statistical yearbook Las Cifras de la Educación en España by the MECD. All authors participated in the interpretation of the data. We followed Yin (2018) to ensure the rigour and credibility of the data and to analyse the statistical data.

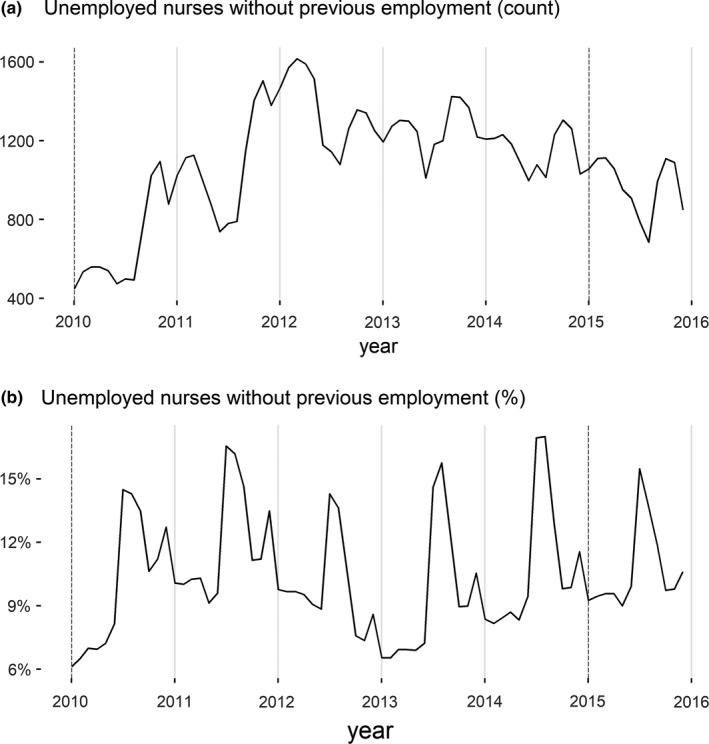

Figure 3.

Number and percentage of unemployed nurses without previous employment with respect to the total number of unemployed nurses

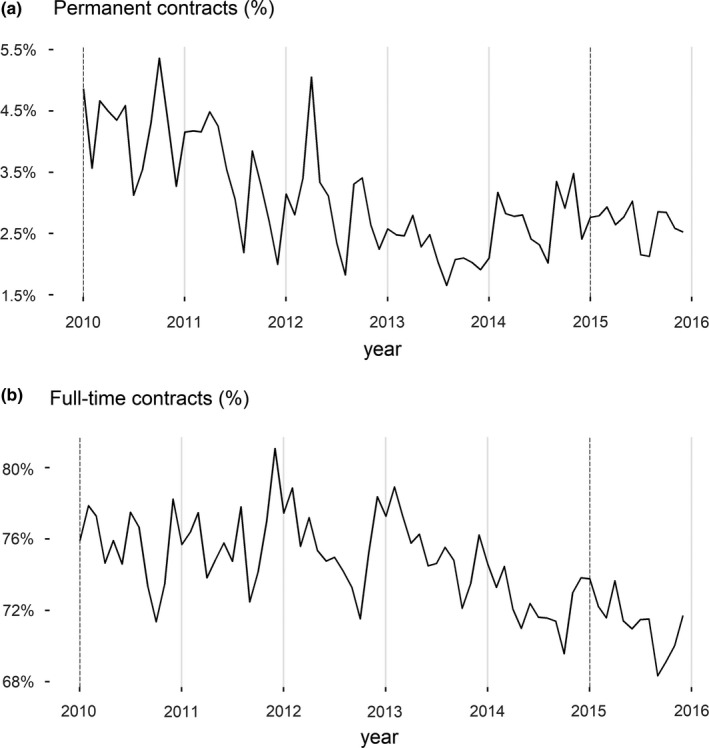

Figure 5.

Percentage of permanent and full‐time contracts with respect to the total number of contracts

3. RESULTS

3.1. Hypothesis 1

Between 2010 and 2015, the variation in the number and percentage of unemployed nurses without previous nursing employment is related to the variation in the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad.

Figure 3a shows the change over time in the number of unemployed nurses without previous employment, while Figure 3b shows the percentage of persons as a percentage of overall nursing unemployed.

Figure 3a shows two different periods. The first (January 2010–August 2012) is characterized by a sudden increase in the number of unemployed people and marked seasonality. The second (September 2012–December 2015) shows a slight decrease in the number of nursing unemployed without previous employment and lower seasonality. Figure 3b also shows two periods. The first (January 2010–January 2013) shows that the percentage of nursing unemployed without previous employment with respect to the total number of nursing unemployed rose, but later it fell to levels similar to those at the beginning of the period. The second phase (January 2013–December 2015) is characterized by a notable peak in the percentage of unemployed nurses without previous employment in July and August each year, with respect to total unemployed nurses. These figures likely represent the new nursing graduates that the profession failed to incorporate. During this phase, we also see that each year, the minimum percentage of unemployed nurses increased with respect to the previous year.

Comparing these two graphs, they reveal two other relevant points. First, despite the fact that the number of unemployed nurses without previous employment decreased starting in August 2012, the percentage with respect to the total of unemployed nurses increased. This pattern implies that increased hiring benefited nurses with previous work experience more than nurses with no previous work experience. In other words, starting in January 2013, the number of unemployed, job‐seeking nurses who prioritized finding work in nursing and who had no previous nursing employment decreased, but less than the number of unemployed, job‐seeking nurses with previous experience. Second, looking at Figure 3a we see that the number of unemployed nurses without previous employment decreased every July, August and December. This pattern suggests that nurses were being hired off the unemployment rolls to cover summer and Christmas vacations. However, if we look at Figure 3b, we can see that during these months, the percentage of unemployed nurses without previous nursing employment increased with respect to the total population of unemployed nurses. This pattern seems to indicate that employers hired nurses with previous experience (drawn from the stock of unemployed and precariously employed nurses) to cover for nurses on vacation.

In this period, the increase in accreditation applications between 2010 and 2012 (Figure 1) coincided with an increase in unemployed nurses without previous nursing employment (Figure 3a). The decrease in accreditation applications between 2013 and 2015 (Figure 1) coincided with a decrease in the number of nurses without previous nursing employment but with an increase in this group as a percentage of the total number of unemployed nurses. Hypothesis 1 is confirmed.

3.2. Hypothesis 2

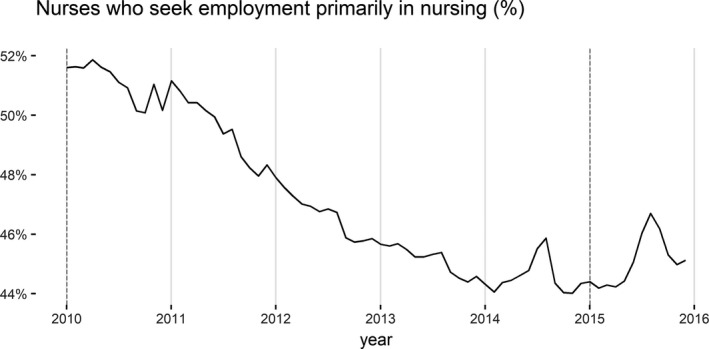

Between 2010 and 2015, the variation in the percentage of nursing graduates that sought employment in nursing is related to the variation in the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad.

The Bachelor of Nursing was launched in some Spanish universities during the 2009–2010 school year and in the rest of Spanish universities during the 2010–2011 school year. This change meant that nursing studies went from a three‐year university certificate programme to a four‐year Bachelor's degree. This shift caused a lag in the entry of new nurses into the labour market, as their training went from three years to four. The first class of nurses graduating with a Bachelor's degree graduated in the summer of 2013 (Galbany‐Estragués & Nelson, 2016).

Figure 4 shows the percentage of unemployed nursing jobseekers who listed nursing as their first choice for employment (as explained above, unemployed nursing jobseekers who list nursing as their first choice are classified as “unemployed nurses”) with respect to the total nursing jobseekers who listed nursing as one of the fields in which they sought work. The figure shows that between January 2010 and February 2014, unemployed nursing jobseekers who listed nursing as their first choice fell from 52% to 44%, which likely indicates that numerous jobseekers dropped out of the nursing profession in favour of other fields. This percentage remained stable in 2014 (if we set aside seasonal variation) and only began to increase starting in January 2015, when nursing employment showed clear signs of improvement. At this point, the percentage of nursing jobseekers who listed nursing as their first choice began to increase.

Figure 4.

Unemployed nursing jobseekers whose first choice is employment in nursing (as a percentage of total unemployed jobseekers who list nursing as a choice)

Between 2010 and 2013, there were no seasonal fluctuations indicating new nursing graduates entering the market; this pattern suggests that they may have dropped out of the profession or migrated. However, after the summer of 2014, when most universities graduated their first classes of nurses, we can once again see marked seasonal variation in unemployment registrations, with spikes in the summer months likely representing new graduates.

Thus, between 2010 and 2014 greater numbers of accreditation applications seem to have coincided with greater levels of professional dropout (Figure 1). Likewise, accreditation applications decreased in 2015 while at the same time more jobseekers listed nursing as their first choice. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

3.3. Hypothesis 3

Between 2010 and 2015, the variation in the quality of contracts, measured by their length and time commitment, is related to the variation in the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad.

Figure 5a shows the percentage of new permanent contracts with respect to the total number of new contracts by month. This percentage dropped from approximately 4.5% in 2010 to 2.0% in 2013, before rising to 2.5% in 2015.

Figure 5b shows the percentage of full‐time contracts and reveals that between January 2010 and January 2013, when nursing unemployment increased, the percentage of full‐time contracts remained more or less stable. However, starting in 2013, during a period when nursing unemployment decreased, the percentage of full‐time contracts fell slightly from 76% in 2013 to 73% in 2015.

Thus, the increase in accreditation applications between 2010 and 2012 (Figure 1) coincided with a reduction in the percentage of permanent contracts, while the percentage of full‐time contracts remained the same. In contrast, the decrease in nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad coincided with a slight increase in the percentage of permanent contracts and a decrease in the percentage of full‐time contracts.

In short, the number of nurses applying for accreditation to work abroad (understood as the intention to migrate) rose when the proportion of temporary contracts rose and fell when the proportion of temporary contracts dropped and the available work was distributed through part‐time contracts. Hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

3.4. Hypothesis 4

Considering that the number of accreditation applications for work abroad in 2010 and 2015 is very similar, the indicators of job security will also be similar for these 2 years.

We have seen that between 2010 and 2012, the number of accreditation applications quadrupled and between 2012 and 2015 they fell to one fifth of the 2012 figure (Figure 1). We have also seen that the overall employment rates in 2010 and 2015 were nearly equal (Figure 2). Using Figures 3 and 5, we now review variations in the job security indicators: Figure 3 shows that the number of unemployed nurses without previous nursing employment remained above the 2010 values, which implies that access to the profession for new graduates had worsened, especially if we keep in mind the mitigating factor of the change in nursing studies from a certificate programme to a Bachelor's of Nursing (creating a year‐long gap in the entry of new graduates into the labour market). Figure 4 shows that between 2010 and 2015 the percentage of nurses listing nursing employment as their first choice fell from 51% to 45% on average. Finally, Figure 5 shows that the percentage of permanent contracts dropped from 4.5% to 2.5% and that the percentage of full‐time contracts dropped from 76% to 73%.

In order to confirm hypothesis 4, we would need to find similar figures for the indicators of job security for 2010 and 2015. However, this is not the case. On average, the overall number of unemployed nurses was 37% higher in 2015 than in 2010 (9,540 vs. 6,969). The number of unemployed nurses without previous employment was 49% higher (975 vs. 655), and the number of nursing jobseekers was 42% higher (35,883 vs. 25,247). Finally, the percentage of temporary contracts was 1.5% higher, while the percentage of part‐time contracts was 4.25% higher. Therefore, hypothesis 4 is disconfirmed.

4. DISCUSSION

We have confirmed hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 and disconfirmed hypothesis 4, showing an important relationship between emigration and job security indicators. Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 demonstrate that the increase in applications for accreditation to work abroad coincided with an increase in unemployment among nurses without previous employment in nursing, in nursing dropout and in a decrease in permanent contracts. In contrast, the decrease in accreditation applications coincided with a decrease in unemployment among nurses without previous employment, an increase in permanent contracts, a greater distribution of work through part‐time contracts and, later, a tendency to prioritize working as a nurse. The disconfirmation of hypothesis 4 suggests that accreditation applications returned to 2010 levels in 2015 because many applicants gave up their first choice of working in nursing and because there were more temporary contracts and a greater distribution of work through part‐time contracts.

The exceptional increase in the number of unemployed nurses is related to the increase in applications for accreditation to work abroad. This trend reversed beginning in 2012, one year before the apex in the number of unemployed people, because in that year there were 31% fewer nursing graduates because of the shift from certificate programme to Bachelor's degree. The drop in the number of unemployed nurses and therefore the number of accreditation applications was also due to the fact that between 2010 and 2014, nursing jobseekers increasingly prioritized finding work in other professions.

This trend began to reverse in 2014 when most universities provided the labour market with their first graduating classes of nurses. Another factor that explains the decrease in the number of unemployed people beginning in 2013 is the increase in the percentage of part‐time and permanent contracts. Granero‐Lazaro et al. (2017) point out that the non‐renewal of contracts is one of the greatest causes of unemployment in nursing. Other research shows that new nursing graduates list unemployment and lack of job security among their motives for emigrating (Gea‐Caballero et al., 2019; Jiménez, Fernández, & Granados, 2014), but these factors encourage some nurses to seek further education in Spain (Abades et al., 2017).

The confirmation of hypothesis 2 suggests that Spain loses nurses through emigration and through professional dropout within Spain, when nurses decide to find work in other fields (Girbau et al., 2012).

Finally, as we see in hypothesis 3, low‐quality contracts appear to have been used to respond to cutbacks resulting from the crisis. These practices were condemned by the European Court of Justice, which pointed out that Spanish legislation conflicts with European Union Rule of Law, because it allows temporary contracts to systematically meet permanent, structural needs (EUR‐Lex, 2016). Galbany‐Estragués and Nelson (2018) reported that an increase in part‐time contracts was used in Spain between 1999 and 2007 as a strategy to retain nurses and prevent emigration.

Although the number of applications for accreditation to work abroad was similar in 2010 and 2015, the indicators for job security were not (hypothesis 4 disconfirmed). We can therefore deduce that by 2015, the number of accreditation applications had fallen to the 2010 rate at the expense of greater job security. The drop in accreditation applications hides the fact that thousands of new nurses appear to have changed professions in order to remain in Spain or else had already emigrated. These data coincide with the perception of Spanish nurses that working conditions in the profession have worsened since the financial crisis (Cervero‐Liceras et al., 2015; Muñoz et al., 2017).

4.1. Limitations

Job security is difficult to define. We have only taken into account factors reported for both nursing and for all professions by the SEPE.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We have explained how different indicators for job security related to the variations in nurses’ intention to migrate from Spain to elsewhere in the EU (as measured by applications for accreditation to work abroad). The number of accreditation applications in Spain in 2010 and 2015 was very similar, but the drop in intention to migrate by Spanish nurses was not linked to a return to 2010 levels of job security. Between 2010 and 2015, job security worsened on a number of fronts: poor access to the profession for new graduates, increased rate of professional dropout, increased number of nursing jobseekers and falling numbers of permanent contracts. However, the distribution of work through part‐time contracts aided retention. These results can aid administrators and policymakers in Spain and elsewhere as they consider how to retain nurses and discourage nursing brain drain.

6. IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING MANAGEMENT

We have revealed the vulnerability of new Spanish nursing graduates to high unemployment conditions and their apparent loss to the workforce through either migration or other career choices. We have also shown the sensitivity of the nursing labour force to initiatives such as short‐term contracts, which nurses appear to favour over emigration. Our analysis highlights the need for workforce planners to be cognizant of system‐wide factors in their responses to major government policy shifts. The study will be of particular salience for countries at risk of major workforce losses through emigration during times of economic crisis.

AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTIONS

PGE, PMM: Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; PGE, PMM, MPB, SN: Been Involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; PGE, PMM, MPB, SN: Given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; PGE, PMM, MPB, SN: Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Because we used publicly available statistics, no consent process was necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We recognize Susan Frekko for providing feedback on the manuscript and for translating it from Spanish into English.

Galbany‐Estragués P, Millán‐Martínez P, Pastor‐Bravo MDM, Nelson S. Emigration and job security: An analysis of workforce trends for Spanish‐trained nurses (2010–2015). J Nurs Manag. 2019;27:1224–1232. 10.1111/jonm.12803

Paola Galbany‐Estragués and Pere Millán‐Martínez should be considered joint first author

REFERENCES

- Abades, M. , Campillo, B. , Guillaumet, M. , Satesmases, S. , Hernández, E. , & Román, E. M. (2017). Inserción laboral de los titulados de una escuela universitaria de enfermería (2009–2016). Enfermería Docente, 2(109), 11–17. Retrieved from http://www.revistaenfermeriadocente.es/index.php/ENDO/article/view/486 [Google Scholar]

- Baranda, L. (2017). Estudi sobre la salut, estils de vida i condicions de treball de les infermeres i infermers de Catalunya. Informe de resultats. Fundació Galatea i Consell de Col.legis d’Infermeres i Infermers de Catalunya. Retrieved from http://www.consellinfermeres.cat/wp-content/uploads/Salut-estils-de-vida-i-condicions-de-treball-de-les-Infermeres-i-Infermers-de-Catalunya.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J. , Julià, M. , Tarafa, G. , Mir, J. , Molinero, E. , & Vives, A. (2015). La precariedad laboral medida de forma multidimensional: Distribución social y asociación con la salud en Cataluña. Gaceta Sanitaria, 29(5), 375–378. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J. , Vives, A. , Amable, M. , Vanroelen, C. , Tarafa, G. , & Muntaner, C. (2014). Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 229–253. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan, J. (2015). ‘Solving’ nursing shortage. Do we need a new agenda? Journal of Nursing Management, 23, 543–545. 10.1111/jonm.12315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchell, B. , Sehnbruch, K. , Piasna, A. , & Agloni, N. (2014). The quality of employment and decent work: Definitions, Methodologies, and ongoing debates. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(2), 459–477. 10.1093/cje/bet067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caravaca, I. , González‐Romero, G. , & López, P. (2017). Crisis y empleo en las ciudades españolas. EURE (Santiago), 43(128), 31–54. https://idus.us.es/xmlui/handle/11441/53136. 10.4067/S0250-71612017000100002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero‐Liceras, F. , McKee, M. , & Legido‐Quigley, H. (2015). The effects of the financial crisis and austerity measures on the Spanish health care system: A qualitative analysis of health professionals’ perceptions in the region of Valencia. Health Policy, 119(1), 100–106. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Union Law (EUR‐Lex) (2016). Sentencia del tribunal de justicia (Sala Décima) de 14 de septiembre de 2016. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62015CJ0016 [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M. (2014). Dimensiones de la precariedad laboral: Un mapa de las características del empleo sectorial en la Argentina. Cuadernos de Economía, 33(62), 231–257. Retrieved from https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?xml:id=282130698010. 10.15446/cuad.econ.v33n62.43675 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galbany‐Estragués, P. , & Nelson, S. (2016). Migration of Spanish nurses 2009–2014. Underemployment and surplus production of Spanish nurses and mobility among Spanish registered nurses: A case study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 63, 112–123. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbany‐Estragués, P. , & Nelson, S. (2018). Factors in the drop in the migration of Spanish‐trained nurses: 1999–2007. Journal of Nursing Management, 26, 477–484. 10.1111/jonm.12573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gea‐Caballero, V. , Castro Sánchez, E. , Díaz‐Herrera, M. A. , Sarabia Cobo, C. , Juárez‐Vela, R. , & Zabaleta‐Del Olmo, E. (2019). Motivations, beliefs, and expectations of spanish nurses planning migration for economic reasons: A Cross‐Sectional Web Based Survey. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 51(2), 178–186. 10.1111/jnu.12455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girbau, R. , Galimany, J. , & Garrido, E. (2012). Desgaste profesional, estrés y abandono de la profesión en enfermería. Nursing, 30(1), 58–61. 10.1016/S0212-5382(12)70016-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granero‐Lazaro, A. , Blanch‐Ribas, J. M. , Roldán‐Merino, J. F. , Torralbas‐Ortega, J. , & Escayola‐Maranges, A. M. (2017). Crisis in the health sector: Impact on nurses? Working Conditions. Enfermería Clínica, 27(3), 163–171. 10.1016/j.enfcle.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, A. , Fernández, C. , & Granados, M. (2014). Cuando la vocación debe llevarse más allá de las fronteras españolas. Rev Paraninfo Digital, 20. Retrieved from http://www.index-f.com/para/n20/pdf/170.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74, 1–22. 10.1177/000312240907400101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. S. , Arango, J. , Hugo, G. , Kouaouci, A. , Pellegrino, A. , & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. 10.2307/2938462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport (2018). Statistical education indicators. The Figures of Education in Spain. Retrieved from http://www.mecd.gob.es/redirigeme/?ruta=/servicios-al-ciudadano-mecd/estadisticas/educacion/indicadores-publicaciones-sintesis/cifras-educacion-espana.html [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Employment and Social Security (2018). Public Service for State Employment. Monthly Labour Market Information by Occupation. Retrieved from https://www.sepe.es/indiceBuscaOcupaciones/indiceBuscaOcupaciones.do?idioma=es [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, J. , Martínez, N. A. , Lázaro, M. , Carranza, A. , & Martinez, M. (2017). Análisis de impacto de la crisis económica sobre el síndrome de Burnout y resiliencia en el personal de enfermería. Enfermería Global, 16(2), 315–335. 10.6018/eglobal.16.2.239681. Retrieved from http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/eg/v16n46/1695-6141-eg-16-46-00315.pdf [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S. (2013). Global trends, local impact: The new era of skilled workers migration. Nursing Leadership, 26, 84–88. 10.12927/cjnl.2013.23254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, K. (2015). Migration theories: A critical overview In Triandafyllidou A. (Ed.), Routledge handbook of immigration and refugee studies (pp. 25–33). Oxford, UK: Abingdon; Retrieved from https://www.routledge.com/products/9781138794313 [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2015). Changing patterns in the international migration of doctors and nurses to OECD countries In OECD (Ed.), International migration outlook (pp. 105–182). Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 10.1787/migr_outlook-2015-6-en. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/international-migration-outlook-2015/changing-patterns-in-the-international-migration-of-doctors-and-nurses-to-oecd-countries_migr_outlook-2015-6-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Salami, B. , Nelson, S. , Hawthorne, L. , Muntaner, C. , & McGillis Hall, L. (2014). Motivations of nurses who migrate to Canada as domestic workers. International Nursing Review, 61, 479–486. 10.1111/inr.12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe, A. A. I. N. , & Wimalaratana, W. (2016). International migration and migration theories. Social Affairs, 1(5), 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. (2018). Case study research: Design and method (6th ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]