Abstract

Aim

To examine the available evidence on the effects of care and support provided by volunteers on the health outcomes of older adults in acute care services.

Background

Acute hospital inpatient populations are becoming older, and this presents the potential for poorer health outcomes. Factors such as chronic health conditions, polypharmacy and cognitive and functional decline are associated with increased risk of health care‐related harm, such as falls, delirium and poor nutrition. To minimise the risk of health care‐related harm, volunteer programmes to support patient care have been established in many hospitals worldwide.

Design

A systematic scoping review.

Methods

The review followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) (File S1). Nine databases were searched (CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ScienceDirect and JBI) using the following key terms: ‘hospital’, ‘volunteer’, ‘sitter’, ‘acute care’, ‘older adults’, ‘confusion’, ‘dementia’ and ‘frail’. The search was limited to papers written in English and published from 2002–2017. Inclusion criteria were studies involving the use of hospital volunteers in the care or support of older adult patients aged ≥ 65 years, or ≥ 50 years for Indigenous peoples, with chronic health conditions, cognitive impairment and/or physical decline or frailty, within the acute inpatient settings.

Results

Of the 199 articles identified, 17 articles that met the inclusion criteria were critically appraised for quality, and 12 articles were included in the final review.

Conclusions

There is evidence that the provision of volunteer care and support with eating and drinking, mobilising and therapeutic activities can impact positively upon patient health outcomes related to nutrition, falls and delirium. Further robust research is needed to determine the impact of volunteers in acute care and the specific care activities that can contribute to the best outcomes for older adults.

Relevance to clinical practice

Volunteers can play a valuable role in supporting care delivery by nurses and other health professionals in acute care services, and their contribution can improve health outcomes for older adults in this setting.

Keywords: clinical outcomes, confusion, frailty, hospital, nursing, older adults, Volunteers

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Volunteers play a valuable role in supporting care delivery in acute care services, and their contribution can improve health outcomes for older adults in this setting.

The review findings enhance understanding of the impact of volunteers on health outcomes and could potentially inform decisions relating to the design of volunteer programmes, volunteering roles and evaluations of volunteer care and support for older adults in acute care.

1. INTRODUCTION

Internationally, older adults constitute the majority of hospital patients, and even though health of older adults is varied, many have chronic health conditions, polypharmacy and cognitive and/or functional decline (George, Long, & Vincent, 2013). These factors are associated with increased risk of health care‐related harm (Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health, & Welfare, 2017; Slawomirski, Auraaen, & Klazinga, 2017). It is also suggested that older adults experience disproportionate harm in hospital due to a lack of attention to older adult health status within nonspecialised clinical settings (Fitzsimmons, Goodrich, Bennett, & Buck, 2014). Confronted with unfamiliar surroundings and routines, admission to an acute hospital for older adults can also cause feelings of vulnerability, anxiety and confusion, which may result in deterioration in physical and mental well‐being (Bateman, Anderson, Bird, & Hungerford, 2016; Hall, Brooke, Pendlebury, & Jackson, 2017).

The length of time patients spend in hospital is said to be directly proportional to their age (AIHW, 2017). A prolonged length of stay for older adults is associated with an increased risk of falls, incontinence, dehydration, poor nutrition, immobility, functional deterioration and depression (George et al., 2013; Hall et al., 2017). Indeed, keeping older adults emotionally and physically safe in hospital has become a global healthcare challenge (George et al., 2013). Strategies to maintain health and well‐being and to minimise health care‐related harm of hospitalised older adults are being implemented worldwide (Baczynska, Lim, Sayer, & Roberts, 2016). The use of volunteers in acute care has been reported to be a proactive strategy to support older adults, particularly as volunteer programmes may not require fiscal resources (Naylor, Mundle, Weaks, & Buck, 2013). Many hospitals have established a nonpaid volunteer workforce who plays a critical role in providing support services that hospitals would otherwise not be able to deliver (Baczynska et al., 2016). A survey by Galea, Naylor, Buck, and Weaks (2013) estimates approximately 78,000 volunteers are working in acute hospitals in England, contributing more than 13 million work hours per year. Babudu, Trevithick, and Spath (2016) completed an evaluation of the impact of volunteering and attributed the increasing contribution of hospital volunteers to improving the experiences of vulnerable older adults in hospital.

While many volunteers undertake traditional befriending and hospital visiting roles, engaging patients in one‐to‐one social interactions and conversations (Charalambous, 2014), the roles undertaken by volunteers are diversifying, as volunteering opportunities are increasingly designed around key organisational priorities (Fitzsimmons et al., 2014). These include the need for better care for patients with dementia, improved hydration and nutrition for elderly patients, and the prevention of falls in hospitals (Fitzsimmons et al., 2014).

While volunteers have predominantly been involved in providing indirect care, increasingly, there are examples indicating volunteers can be trained to deliver direct care (Roberts et al., 2014). Volunteers have been successfully trained to provide targeted feeding assistance to improve nutrition for older patients (Manning et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2017; Walton et al., 2008), for dysphagic patients (Wright, Cotter, & Hickson, 2008) and for patients with dementia (Wong, Burford, Wyles, Mundy, & Sainsbury, 2008). Other studies have reported on the effectiveness of using volunteers trained to prevent falls in hospital, to observe patients at high risk of falling and to engage patients through conversation and social interaction, and alert staff when changes in patient behaviour may increase their risk of falls (Donoghue, Graham, Mitten‐Lewis, Murphy, & Gibbs, 2005; Giles et al., 2006). Volunteer‐mediated interventions to prevent delirium have also been reported (Caplan & Harper, 2007). The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), which uses multicomponent physical, nutritional and cognitive strategies, is another example of including volunteers as a key intervention strategy. The HELP, now implemented successfully around the world, has been shown to improve the quality of care and health outcomes for hospitalised older adults. Positive outcomes include: maintaining cognitive and physical functioning of high‐risk patients during hospitalisation, maximising independence at discharge, assisting with the transition from hospital to home and preventing unplanned hospital readmissions (Hshieh, Yang, Gartaganis, Yue, & Inouye, 2018; Steunenberg, van der Mast, Strijbos, Inouye, & Schuurmans, 2016).

There is wide‐scale growth, in both the quantity and diversity of volunteers’ roles, within the acute hospital setting, all aimed at improving care and safety while enhancing the overall patient experience. However, there is limited synthesised evidence of the impact of volunteering on intended and unintended patient outcomes. One previous review has reported on the effect of volunteers on a discrete patient group, those with dementia (Hall et al., 2017). However, to date there has been no previous attempts to synthesise the evidence relating to older adult patients more broadly. We therefore undertook a systematic scoping review to explore the effect of volunteers on the health outcomes of older adults in acute care.

2. AIM

To examine the available evidence on the effects of care and support provided by volunteers on the health outcomes of older adults in acute care services.

3. METHODS

3.1. Search methods

This scoping review was conducted systematically using the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) (see File S1) (Tricca et al., 2018). The search was performed using a combination of search terms, including ‘hospital’ AND ‘acute’ AND ‘volunteer’ OR ‘sitter’ OR ‘companion’ OR ‘aid’ OR ‘assistant’ AND ‘older adults’ OR ‘elderly’ OR ‘senior’ AND ‘confusion’ OR ‘dementia’ OR ‘delirium’ OR ‘frail’, and all appropriate synonyms thereof, across nine databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ScienceDirect and JBI, as outlined in Appendix S1. The search was limited to papers written in English and published only within the last 15 years (January 2002 and December 2017) for clinical relevancy. We included studies reporting on all intervention types and observational designs, with the exception of quality improvement studies, in order to scope the range of volunteering activities undertaken with older adults in acute care. The search was deliberately boarded, as we wanted to gauge the breadth of interventions and observations conducted, and the variety of outcomes studied. Exclusion criteria were as follows: paid sitters or assistants, sitting done by nurses or assistants in nursing (AINS), and theoretical, discussion or review papers. Additionally, studies were excluded if we could not disaggregate the contribution of volunteering activities from that of health professionals or other activities, in improving patient outcomes.

3.2. Search outcome

Studies were selected using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement process of identification, screening and assessment of eligibility (Liberati, 2009). Duplicates were identified and excluded. The reference lists of all included studies were reviewed to identify any relevant papers not captured through electronic searches. A manual search was also conducted on the reference lists of seven relevant, published systematic reviews (Baczynska et al., 2016; Edwards, Carrier, & Hopkinson, 2017; Ellis, Mant, Langhorne, Dennis, & Winner, 2010; Green, Martin, Roberts, & Sayer, 2011; Horey, Street, O’Connor, Peters, & Lee, 2015; Jenkinson et al., 2013; Tassone et al., 2015). The titles and abstracts of citations were reviewed independently and blindly by three reviewers (AC, RS and RG), and a consensus process was then used to determine whether papers were retrieved in full before being appraised independently by two reviewers (AC and RS) for eligibility.

3.3. Quality appraisal

Articles that met the inclusion criteria were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardised critical appraisal checklists: ‘Checklist for Quasi‐Experimental Studies’ and ‘Checklist for Cohort Studies’ (Lockwood et al., 2017). Two reviewers reviewed each study independently. Where consensus was not reached, the third reviewer conducted quality appraisal independently, and the review team discussed discrepancies until a resolution was reached.

3.4. Data extraction

Study characteristics were tabulated, and study outcomes were extracted, assessed and categorised, using the JBI tools for data extraction. One author performed the data extraction, and two authors verified the data extraction. Studies were synthesised, sorted accordingly into three key themes and summarised narratively.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Search results

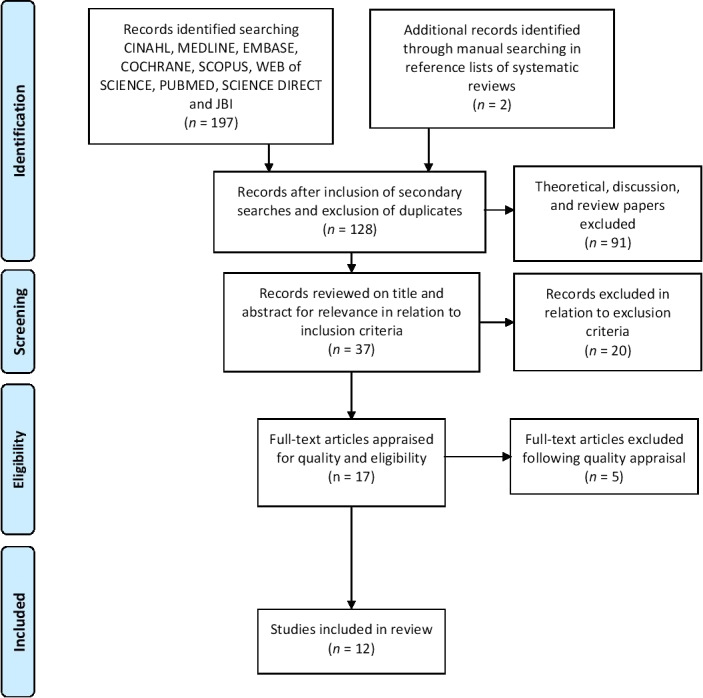

A total of 197 citations were identified from the electronic searches and a further two from manual searches of seven systematic reviews. The exclusion of duplicates and the addition of secondary searches of reference lists resulted in the identification of 128 citations. A review of titles and abstracts identified 37 articles that met the review's inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 17 articles were reviewed for quality and eligibility. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search

4.2. Quality of studies

The critical appraisal scores for each of the 17 appraised studies are outlined in Table 1. Two studies were classified as cohort studies (Donoghue et al., 2005; Giles et al., 2006). The remaining studies were classified as quasi‐experimental. Five studies were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: not being specific to volunteers (Mudge, Maussen, Duncan, & Denaro, 2013), no reported outcomes (Strijbos, Steunenberg, van der Mast, Inouye, & Schuurmans, 2013) or conducted as an audit or quality improvement project (Brown & Jones, 2009; Rubin, Neal, Fenlon, Hassan, & Inouye, 2011; Rubin et al., 2006). Twelve studies were included in the systematic scoping review.

Table 1.

Assessment of methodological quality

| Citation | JBI Tool | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bateman et al. (2016) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Brown and Jones (2009) | Quasi | N | N | N | N | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Exclude | ||

| Caplan and Harper (2007) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Donoghue et al. (2005) | Cohort | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Include |

| Giles et al. (2006) | Cohort | N | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Include |

| Gorski et al., 2017 | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Huang et al. (2015) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Include | ||

| Manning et al. (2012) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Mudge et al. (2013) | Quasi | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Exclude | ||

| Roberts et al. (2017) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Robinson et al. (2002) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | Include | ||

| Rubin et al. (2006) | Quasi | Y | N | N | N | N | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Exclude | ||

| Rubin et al. (2011) | Quasi | Y | N/A | N/A | N | N | N/A | Y | U | Y | Exclude | ||

| Strijbos et al., 2013 | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | Exclude | ||

| Walton et al. (2008) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Wong et al. (2008) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Include | ||

| Wright et al. (2008) | Quasi | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Include |

Abbreviations: Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear; N/A, not applicable.

4.3. Study characteristics

The primary outcomes for the 12 studies focused on three main areas: delirium, falls and nutrition. The characteristics of the 12 studies included in the review are outlined in Table 2. The studies ranged in publication date from November 2002 (Robinson et al., 2002)–May 2017 (Roberts et al., 2017). Ten of the studies used quasi‐experimental designs, of which four conducted matched (controlled) before and after studies and six conducted one group (uncontrolled) before and after study designs. The remaining two studies were prospective descriptive cohorts. Seven studies were conducted in Australia, two in the UK, one in Europe, one in New Zealand and one in the USA. The reported settings for the studies varied from rural to metropolitan hospitals, with the majority of the studies conducted in metropolitan areas. The type of wards described included rehabilitation, geriatric, medical and general wards. Duration of data collection varied and was often reported as an observation period. The observation periods ranged from four days–eighteen months.

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| Author, year and location | Study design and setting | Number of participants, age and condition | Type of volunteer care intervention, duration of data collection and number of type of volunteers | Comparison/control and duration of data collection | Outcomes measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium | |||||

| Bateman et al. (2016) Australia |

Quasi‐experimental; one group before and after Acute rural hospital |

Total 64 patients (Int‐G = last 15 patients enrolled; Cont‐G = first 15 patients enrolled) Aged ≥ 65 years (or ≥ 50 years for Aboriginal persons) Dementia/delirium diagnosis, known risk factors for delirium or SMMSE < 25/30 |

Person‐centred volunteer care weekdays 08.00–12.30 and 15.00 to 19.00 (data recorded over 8 months) Int: General conversation, feeding/hydration, vision/hearing assistance, reassurance and encouraging ambulation Number of volunteers = 18 Type—many previously in caring profession |

Beginning of project (data recorded over 8 months) |

Use of analgesics on discharge Use of antipsychotics/psychotropic medications Length of stay, days Falls, n Delirium, n |

| Caplan and Harper (2007) Australia |

Quasi‐experimental; one group before and after Suburban tertiary hospital, one ward, acute and rehab geriatric unit |

37 patients (Int‐G n = 16; Cont‐G n = 21) Aged ≥ 70 years Frailty—at least one risk factor for dev. delirium Int‐G mean age = 85.6 ± 7.4 Cont‐G mean age = 83.8 ± 4.7 |

REVIVE volunteer delirium prevention programme weekdays 14.00 to 19.00 (data recorded over 5 months) Int: Daily orientation, therapeutic activities, feeding/hydration assistance and vision/hearing protocols Number of volunteers = No information provided Type—no information provided |

Standard care (data recorded over 5 months) |

Delirium incidence/severity (MDAS)/duration Cognitive function (MMSE) Falls, n Residential aged care placement, n Unplanned readmission, n Frailty/physical function (Barthel Index) Length of stay, days |

| Gorski et al. (2017) Europe |

Quasi‐experimental; one group before and after Tertiary Hospital Acute Care Medical Ward |

130 patients (Int‐G n = 65; Con‐G n = 65) Aged ≥ 75 years Int‐G mean age = 84.9 ± 5.3 Cont‐G mean age = 84.4 ± 5.6 Admitted for acute condition from Emergency Department |

Initial 5 days of hospitalisation (begin within 48 hr of admission)—trained volunteer‐based assistance (data recorded after intervention) Int: Education and assistance in disorientation, psychological distress, immobility, dehydration, malnutrition, sensory deprivation and sleep problems Number of volunteers = 18 Type—HP Students |

Standard Care (data retrospectively matched before intervention) |

Length of stay, days Antipsychotic drugs during hospitalisation Falls, n In‐hospital death, n Delirium, n |

| Falls | |||||

| Donoghue et al. (2005) Australia |

Prospective descriptive study; Hospital Acute Aged Care Unit, one ward |

One ward, Patients high falls risks, allocated to 4‐bed CO room next to nurse station—pilot 2nd 4‐bed CO room added next to nurse station—extended study |

Volunteer Companion Observers (C.O’s) weekdays 08:00 to 20:00 (data recorded after intervention) Pilot study 6 months; Number of volunteers = 26 Extended study 18 months; Number of volunteers = 128 C.O’s Int: Observe patients for increase agitation/risky behaviour and notify nurse if patient attempted to move General conversation, activities and practical assistance C.O. walked ward to look for at‐risk patients Type—no information provided |

Standard care (data recorded before intervention) |

Falls/1,000 bed days—observation room Falls/1,000 bed days—aged care ward Multiple falls |

| Giles et al. (2006) Australia |

Prospective descriptive study; Two public hospitals, two wards—geriatric wards |

Two wards Patients high falls risks, allocated to 4‐bed CO room |

Volunteer Companion Observer (C.O) weekdays 09:00 to 17:00 (data recorded 5 months after intervention) Int: Observe patients for risk of falling and notify nurse if patients may fall and change in patients behaviour General conversation, activities and practical assistance Number of volunteers = 45 Type—no information provided |

Standard care (data recorded 5 months before intervention) | Falls/1,000 bed days—wards |

| Nutrition | |||||

| Huang et al. (2015) Australia |

Quasi‐experimental; matched before and after 60‐bed suburban hospital, 2 aged care wards |

8 patients Aged 83 ± 4.5 years Identified ‘at‐risk’ or malnourished by hospital dietician and requiring full assistance with meals and/or requiring encouragement and some assistance at meals. |

Volunteer assists with lunchtime on weekdays (data recorded for 3 main meals, morning tea and afternoon snacks on two weekdays) Int: Assisting included tray position, cutting food, opening packages, handling cutlery and encouragement Number of volunteers = 5 Type—no information provided |

Standard care (data recorded for 3 main meals, morning tea and afternoon snacks on two weekend days) |

Avg. macronutrient and energy intake (Observation) Intake as a % of daily requirement (Schofield equation) |

| Manning et al. (2012) Australia (follow on study by Walton et al., 2008) |

Quasi‐experimental; matched before and after Public suburban hospital, 2 aged care wards |

23 patients Aged > 65 years old referred to programme Age = 83.2 ± 8.9 years |

Volunteer assists with lunchtime feeding on weekdays (data recorded at lunchtime on two weekdays) Int: Assisting included meal tray set‐up, encouragement and general conversation Number of volunteers = No information provided Type—no information provided |

Standard care (data recorded at lunchtime on two weekend days) |

Avg. protein and energy intake (observations and weighed plate) Intake as a % of daily requirement (Schofield equation) |

| Roberts et al. (2017) UK |

Quasi‐experimental; one group before and after Tertiary Hospital Female Acute Medical Ward, two wards |

407 patients; 2 wards (observational year n = 221; intervention year n = 186; 104 Int‐G, 82 Con‐G) Aged ≥ 70 years Female Age = 87.5 ± 5.4 years |

Volunteer feeding assistance during lunchtime on weekdays (data recorded 24‐hr period; 7 days of observational year (over 9 months); 6 days of intervention year (over 8 months) Int: encouragement, opening packages, cutting and feeding patients Number of volunteers = 29 Type—no information provided |

Standard care (data recorded 24‐hr period; 7 days of observational year (over 9 months); 6 days of intervention year (over 8 months) | Avg. protein and energy intake (observations and weighed plate) |

| Robinson et al. (2002) USA |

Quasi‐experimental; one group before and after Large hospital, medical unit |

68 patients (Int‐G n = 34; Cont‐G n = 34) Aged > 65 requiring assistance with feeding Intervention group mean age = 77.8 years Control group mean age = 78.2 years |

Patients feed by Memorial Meal Mates volunteers (number of meals observed not specified) Number of volunteers = 19 Type—college students (79%) |

Standard care (data retrospectively matched before intervention) | Estimation of % of entire tray (food and fluids) (observation) |

| Walton et al. (2008) Australia |

Quasi‐experimental; matched before and after Public suburban hospital, 1 aged care ward |

9 patients Age = 89 ± 4.6 years |

Volunteer feeding assistance during lunchtime weekdays (data recorded at lunchtime on two weekdays) Int: Assisting including meal tray set‐up, encouragement and general conversation Number of volunteers = 25 Type—no information provided |

Standard care (data recorded at lunchtime on two weekend days) |

Avg. protein and energy intake (observations and weighed plate) Intake as a % of daily requirement (Schofield equation) |

| Wong et al. (2008) New Zealand |

Quasi‐experimental; matched before and after Short stay assessment, treatment and rehabilitation unit for older people with cognitive impairment |

7 patients (Intervention) Age = 77.0 ± 6.5 years Dementia |

Phase 3—maximising food and fluid intake by feeding assistance at lunchtime (12 weeks) (number of meals observed not specified) Int: assist semi‐dependent eaters at mealtimes Number of volunteers = No information provided Type—no information provided |

Phase 1—observation Phase 2—encouraging dietary grazing Phase 4—improving dining atmosphere (each phase was 12 weeks) |

Body mass index Anthropometry Avg. energy intake (observation and plate wastage) |

| Wright et al. (2008) UK |

Quasi‐experimental; one group before and after Hospital, several wards |

46 patients (Int‐G n = 16; Cont‐G n = 30) Aged ˃65 years diagnosed with dysphagia Int‐G prescribed a textured‐modified diet and thickened fluids Int‐G Age = 79.1 ± 11.2 years Cont‐G—prescribed texture‐modified diets and ˃60 years Cont‐G Age = 81.8 ± 8.7 years |

Targeting feeding assistance from 8:00–16:00 (data recorded over a 24‐hr period, avg. of 3 days) Int: Assisting included cutting, meal tray set‐up, opening packages, encouragement and general conversation Number of volunteers = 3 Type—HP Student (100%) |

Standard care (data retrospectively recorded before intervention—in a separate study) |

Avg. protein and energy intake (Observation) Intake as a % of daily requirement (Schofield equation) |

4.4. Participant characteristics

The mean age for ‘older adult’ participants ranged from 77–89 years. Some studies did not report exact ages for participants. In an Australian study, Bateman et al. (2016) specified participants were aged greater than 65 years or greater than 50 years for Australian Aboriginal participants. Life expectancy for Indigenous peoples is lower than that of non‐Indigenous peoples; the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population born from 2010–2012 was estimated to be 10.6 years lower than that of the non‐Indigenous population for males (69.1 years compared with 79.7) and 9.5 years lower for females (73.7 years compared with 83.1) (AIHW, 2018). Indigenous Australians also have a higher incidence of dementia at a younger age (Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2019; Flicker & Holdsworth, 2014). Donoghue et al. (2005) and Giles et al. (2006) specified their studies were conducted in aged care wards. There was a variety of participant inclusion criteria across the studies, including participants needing assistance with feeding (Manning et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2002; Walton et al., 2008), risk of a diagnosis of dementia or delirium (Bateman et al., 2016; Caplan & Harper, 2007; Wong et al., 2008), risk of falls (Donoghue et al., 2005; Giles et al., 2006), risk of malnutrition (Huang, Dutkowski, Fuller, & Walton, 2015), dysphagia (Wright et al., 2008) and admission for acute conditions (Gorski et al., 2017).

4.5. Intervention characteristics

The type of volunteer support interventions or exposures varied between the studies. In two studies, the volunteers’ roles focused on well‐being, including conversations, feeding and hydration assistance, and general encouragement for patients (Bateman et al., 2016; Caplan & Harper, 2007). The volunteers’ roles in another study comprised provision of patient education in nutrition and physical activity, and implementation of strategies to alleviate patient disorientation and distress (Gorski et al., 2017). In two studies, the role of the volunteers was to observe patients for risk of falls and provide companionship (Donoghue et al., 2005; Giles et al., 2006). For seven of the twelve studies, the role of the volunteers was to provide feeding assistance, including meal tray set‐up, encouragement and general conversation (Huang et al., 2015; Manning et al., 2012; Walton et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2008).

The number of volunteers involved in each of the interventions or exposures ranged from 3–128, with three studies providing no information on the number of volunteers (Caplan & Harper, 2007; Manning et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2008). Eight studies provided no information on the type of volunteers used, while the remaining four studies’ volunteers included previous health professionals (Bateman et al., 2016), student health professionals (Gorski et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2008) and college students (Robinson et al., 2002). The majority of studies reported volunteers were present during weekdays only. No studies reported volunteers being present on weekends.

4.6. Outcomes

Across the 12 studies, 29 clinical patient outcome measures were collected, which could be grouped under the following subheadings: delirium outcomes, fall outcomes, nutritional outcomes, medication outcomes and other outcomes. Table 3 outlines the results of patients’ clinical outcomes reported within the studies.

Table 3.

Clinical patient outcomes

| Outcome | Author | Control | Intervention | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium outcomes | ||||

| Delirium, n | Bateman et al. (2016)a | 7 (46.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | .72 |

| Caplan and Harper (2007)a | 8 (38.1%) | 1 (6.25%) | .032 | |

| Gorski et al. (2017)a | 12 (18.5%) | 9 (13.8%) | .47 | |

| Delirium severity, MDAS | Caplan and Harper (2007)b | 5.1 ± 6.7 | 1.2 ± 4.8 | .045 |

| Delirium duration, days | Caplan & Harper, 2007b | 12.5 ± 14.5 | 5.0 ± NA | .64 |

| Falls outcomes | ||||

| Falls, n | Bateman et al. (2016)a | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

| Caplan and Harper (2007)a | 4 (19.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | .16 | |

| Donoghue et al. (2005)c | Pilot: 10 | 2 | – | |

| Gorski et al. (2017)a | 3 (4.61%) | 3 (4.61%) | 1 | |

| Falls, 1,000 bed days (mean rate) | Donoghue et al. (2005)c |

Pilot: 16.4 Extended: 15.6 |

8.4 8.8 |

– .000 |

| Giles et al. (2006)c | 14.5 | 15.5 | .346 | |

| Falls multiple, % | Donoghue et al. (2005)a | 32% | 15.5% | <.01 |

| Nutrition outcomes | ||||

| Energy (KJ): Lunchtime | Huang et al. (2015)b | 1,404 ± 638 | 1,720 ± 617 | .175 |

| Manning et al. (2012)b | 1,334 ± 954 | 1,730 ± 891 | .005 | |

| Walton et al. (2008)b | 1,261 ± 772 | 1,700 ± 897 | .072 | |

| Protein (g): Lunchtime | Huang et al. (2015)b | 20.1 ± 12.5 | 23.2 ± 12.0 | .468 |

| Manning et al. (2012)b | 17.5 ± 11.4 | 21.8 ± 10.2 | .009 | |

| Walton et al. (2008)b | 15.2 ± 12.3 | 25.3 ± 15.8 | .015 | |

| Fat (g): Lunchtime | Huang et al. (2015)b | 11.0 ± 4.6 | 12.4 ± 4.2 | .418 |

| Carbohydrates (g): Lunchtime | Huang et al. (2015)b | 38.1 ± 16.4 | 49.7 ± 19.1 | .084 |

| Energy (KJ): Daily | Huang et al. (2015)b | 5,237 ± 766 | 5,484 ± 1,298 | .373 |

| Manning et al. (2012)b | 4,078 ± 2,771 | 4,526 ± 2,349 | .113 | |

| Roberts et al. (2017)d | 4,527, IQR 3339–6084 | 4,456, IQR 2828–5966 | .55 | |

| Walton et al. (2008)b | 3,784 ± 1,800 | 4,018 ± 1,244 | .509 | |

| Wong et al. (2008)b | UK | Δ 44.1 | <.001 | |

| Wright et al. (2008)b | 2,701 ± 1,180 | 5,027 ± 1,798 | <.001 | |

| Protein (g): Daily | Huang et al. (2015)b | 64.4 ± 16.2 | 65.2 ± 26.1 | .873 |

| Manning et al. (2012)b | 43.0 ± 27.6 | 51.7 ± 25.7 | .004 | |

| Roberts et al. (2017)d | 39.1, IQR 29.4–54.8 | 40.1, IQR 23.3–53.4 | .55 | |

| Walton et al. (2008)b | 39.8 ± 21.1 | 50.5 ± 20.3 | .015 | |

| Wright et al. (2008)b | 25 ± 14.5 | 53 ± 25 | .01 | |

| Fat (g): Daily | Huang et al. (2015)b | 41.7 ± 9.4 | 43.6 ± 13.5 | .452 |

| Carbohydrates (g): Daily | Huang et al. (2015)b | 152.3 ± 20.4 | 150.0 ± 37.1 | .848 |

| Energy (KJ): Intake as a % of daily requirement | Huang et al. (2015) | 77.8% | 80.1% | .614 |

| Manning et al. (2012) | 58% | 64% | Non‐sig | |

| Walton et al. (2008) | 51.5% | 54.7% | .478 | |

| Wright et al. (2008)b | 41.6%, 15.6% | 80.4%, 29.5% | <.001 | |

| Protein (g): Intake as a % of daily requirement | Huang et al. (2015) | 98.0% | 95.9% | .755 |

| Manning et al. (2012) | 59% | 71% | .003 | |

| Walton et al. (2008) | 56.0% | 71.0% | .020 | |

| Estimation of mean % of entire tray | Robinson et al. (2002) | 32.5% | 58.9% | <.001 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | Wong et al. (2008)b | 24.3 ± 3.5 | 24.67 ± 0.4 | .04 |

| Mid‐arm circumference (cm) | Wong et al. (2008)b | UK | Δ 0.14 ± 0.24 | Non‐sig |

| Medication outcomes | ||||

| Analgesic, n | Bateman et al. (2016)a | 1 (6.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | .03 |

| Antidepressant, n | Bateman et al. (2016)a | 5 (33.3%) | 6 (40.0%) | .71 |

| Antipsychotic, n | Bateman et al. (2016)a | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | .55 |

| Gorski et al. (2017)a | 21 (32.3%) | 11 (16.9%) | .04 | |

| Benzodiazepine, n | Bateman et al. (2016)a | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | .55 |

| Other outcomes | ||||

| Length of stay, days | Bateman et al. (2016)b | 19.27 ± 13.63 | 9.93 ± 5.22 | .02 |

| Caplan and Harper (2007)b | 26.8 ± 17.8 | 22.5 ± 9.6 | .35 | |

| Gorski et al. (2017)b | 17.9 ± 14.4 | 13.4 ± 7.5 | .05 | |

| Deaths | Bateman et al. (2016)a | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 |

| Gorski et al. (2017)a | 7 (10.8%) | 2 (3.1%) | .14 | |

| Change in MMSE | Caplan and Harper (2007)b | −0.65 ± 6.21 | 3.5 ± 2.8 | .019 |

| Change in ADL (Barthel Index) | Caplan and Harper (2007)b | −5.3 ± 6.6 | 2.0 ± 2.9 | .049 |

| Readmissions, n | Caplan and Harper (2007)a | 4 (19.0%) | 5 (31.3%) | .39 |

| Residential aged care placement, n | Caplan and Harper (2007)a | 10 (47.6%) | 4 (25.0%) | .26 |

Abbreviations: N, number; MDAS, memorial delirium assessment scale; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; ADL, activities of daily living; NA, not applicable; g, grams; KJ, kilojoules; UK, unknown; Δ, change.

Number, %.

Mean, Standard deviation.

Mean falls rate/1,000 occupied bed days.

Median, IQR.

One out of three studies demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of delirium diagnoses; this study also demonstrated a reduction in the severity of delirium (Caplan & Harper, 2007).

One study demonstrated reductions in the total number of falls, falls per 1,000 bed days and the number of multiple falls (Donoghue et al., 2005).

Seven studies reported outcomes relating to dietary intake, including daily or per meal energy (kilojoules or calories) and protein (grams or energy) from food and beverages (Huang et al., 2015; Manning et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2002; Walton et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2008). Four studies specified the inclusion of prescribed oral nutritional supplements alongside meals and snacks (Manning et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2017; Walton et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2008); however, only one study indicated the number of participants (all patients) receiving supplementation (Roberts et al., 2017). One study specified that seven of the eight participants were prescribed a high‐energy, high‐protein diet, though did not clarify whether this included oral nutritional supplements (Huang et al., 2015). Robinson et al. (2002) and Wong et al. (2008) did not report on the use of oral nutritional supplements. Two out of three studies demonstrated an increase in lunchtime energy intakes (Manning et al., 2012; Walton et al., 2008). The same studies demonstrated an increase in lunchtime protein intakes. Six studies explored total daily energy intakes, with two of the six showing increased intakes (Wong et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2008). Five studies explored total daily protein intakes, with three of the five showing increased intakes (Manning et al., 2012; Walton et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2008). One study demonstrated a positive increase in body mass index (BMI) but no difference in mid‐arm circumference (Wong et al., 2008).

Medication use was explored by two studies (Bateman et al., 2016; Gorski et al., 2017). One found a difference in analgesic use (Bateman et al., 2016) and the other in antipsychotic use (Gorski et al., 2017); however, no differences were seen for antidepressants or benzodiazepines.

Two out of three studies demonstrated a reduction in patient length of stay (Bateman et al., 2016; Gorski et al., 2017). One study demonstrated positive changes in scores for MMSE (Mini‐Mental State Examination) and assessments of activities of daily living (ADL) (Caplan & Harper, 2007). Of the two studies looking at the incidence of death, no differences were seen (Bateman et al., 2016; Gorski et al., 2017). One study looked at both hospital readmission and admission into residential aged care, with no differences observed (Caplan & Harper, 2007).

5. DISCUSSION

This systematic scoping review assessed emerging evidence from 12 studies across five countries that reported on the impact of volunteering on older adult patients in acute settings. Three primary outcomes, nutrition, falls and delirium, are identified.

The included studies were predominantly nonmatched, quasi‐experimental interventions, and these would have been more methodologically rigorous had they included control groups. The two included cohort studies were prospective and therefore more rigorous than retrospective observational study designs. There was inconsistency between various studies in the use of intervention measures, and no studies used standard criteria to evaluate the training for volunteers. Older adult patients were not always clearly defined, and two studies did not report the age range of patients (Donoghue et al., 2005; Giles et al., 2006). One study specified a younger age for Indigenous patients compared with non‐Indigenous patients (Bateman et al., 2016), and although there is evidence that Indigenous Australians have a lower life expectancy (AIHW, 2018) and a higher incidence of dementia at a younger age (Agency for Clinical Innovation, 2019; Flicker & Holdsworth, 2014), the authors provided no such justification for the lower cut‐off, presumably because these statistics are largely implicit within the Australian healthcare system.

Some of the studies investigated the impact of volunteer support at mealtimes on nutritional outcomes by evaluating protein and energy intakes. Of those studies that explored dietary outcomes, all identified various positive effects on patients’ nutritional status, indicating volunteers can play a valuable role in assisting older adults in acute settings with eating and drinking (Huang et al., 2015; Manning et al., 2012; Walton et al., 2008). The involvement of volunteers in supporting older adults in mealtime care within nonacute settings has also been examined. While some evidence supports the use of volunteers in this capacity, the lack of robust methodological quality of these studies suggests further research is required (Green et al., 2011). The studies of this review used volunteers during lunchtime meals only, and volunteer assistance could be valuable to patients at other mealtimes; this is supported by other studies involving volunteers to improve dietary outcomes for older adults (Steele, Rivera, Bernick, & Mortensen, 2007).

Other volunteer programmes reported on the impact of volunteers upon patient falls as a clinical outcome. However, approaches to the role of volunteers in preventing falls varied across studies. While one study demonstrated a reduction in fall incidence, this was deemed a result of combined strategies from both clinicians and volunteers (Donoghue et al., 2005). In this study, volunteers did not assist patients with mobilising; a proven strategy for fall prevention identified within other research (Lee, Gibbs, Fahey, & Whiffen, 2013). Rather, the volunteer role was to observe the patient for agitation and report concerns to nursing staff, while using interim strategies to allay patient anxiety. Similarly, in another study, volunteers were engaged to sit with patients assessed as being at high risk of falling, and no falls were reported during volunteer supervision (Giles et al., 2006). This outcome suggests one‐on‐one patient observation facilitated fall reduction. One study in this review reported a nonsignificant but clinically meaningful trend towards a reduction in falls, despite the lack of a specific mobilisation strategy, and the authors suggested that preventing delirium played a role in fall reduction (Caplan & Harper, 2007). In contrast, two other studies reported that volunteers accompanied patients during mobilisation and encouraged them in walking (Bateman et al., 2016; Gorski et al., 2017). However, in these two studies, there were no significant differences observed in the reduction of falls. Other studies have also examined the specific role of volunteers in mobilising older adults in acute care settings; however, due to a lack of convincing evidence, the findings are inconclusive regarding measurable benefits of volunteer‐assisted mobilisation (Baczynska et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the benefits of mobilisation have previously been shown to contribute to patients’ physical, psychological and social well‐being (Lee et al., 2013).

Two studies examined the impact of using volunteers to carry out multicomponent strategies to prevent delirium in older adults in acute care (Caplan & Harper, 2007; Gorski et al., 2017). The incidence of delirium was found to be lower in the intervention group in the first study. The latter study, however, used four surrogate markers for delirium in lieu of standardised delirium assessment tools: length of stay, need for antipsychotic drugs, falls and in‐hospital deaths, and found antipsychotic medications were administered less frequently in the intervention group (Gorski et al., 2017). While these results indicate a positive association between volunteer assistance and reduced delirium, further studies are required using validated cognitive assessment tools, as employed by Caplan and Harper (2007).

Medication use was also identified as a clinical outcome of volunteer programmes for older adult patients. The multicomponent interventions delivered by volunteers in two studies were determined to contribute to modifications in the use of antipsychotics and analgesics in patients (Bateman et al., 2016; Gorski et al., 2017). The recognition by volunteers of patients with symptoms that may indicate pain could have contributed to the increased analgesic use. Pain management is an integral part of care delivery, and the contribution of volunteers in delivering multicomponent intervention strategies and recognising symptoms related to pain, particularly in older adults in acute care, is an area that warrants further investigation, due to the potential for improved outcomes for patients.

From an organisational perspective, two programmes reported cost‐effectiveness in relation to length of patient stay, the estimated value of volunteers’ time and the associated reduction in staffing costs (Caplan & Harper, 2007; Giles et al., 2006). However, due to the small sample sizes in these studies and the limitations of the study designs, the cost‐effectiveness of volunteering programmes for older adults in acute care could not be determined and, hence, should be a focus for future research.

The disparities among the studies’ findings may have been influenced by differences in the volunteer interventions themselves, such as the number of volunteers relative to patients within each ward, the volunteer training protocols (or lack thereof), the total available volunteer hours and the duration of the volunteering programme. None of the reviewed studies determined a set of criteria for volunteer allocation concerning patient illness acuity, and this should certainly be considered, since there may be an inherent bias if volunteers are allocated to patients who are less well. The level of illness of patients has also been noted as an essential consideration when involving volunteers in palliative care (Candy, France, Low, & Sampson, 2015). These findings raise important points for consideration when developing volunteer programmes.

6. LIMITATIONS

The review has two limitations. First, the literature search was limited to articles published in English, creating a possible language bias, and second, the search strategy was limited by year of publication, including only the most recent 15 years of literature. Both limitations may have potentially excluded papers with findings related to the study aim.

7. CONCLUSION

In contrast to previous reviews, which have focussed on single outcomes of volunteering, this systematic scoping review synthesised evidence relating to the impact of volunteering across a range of health outcomes. Despite the methodological limitations of some of the included studies, our scoping review indicates there is evidence to suggest volunteering care and support can impact positively on the health outcomes of older adults in acute care, in relation to nutrition, falls and delirium. The review has generated a new perspective on the benefits of using volunteers for older adults in acute care, highlighting the valuable contribution they can make in several areas of care, including ambulation, mealtime assistance and therapeutic activities.

The findings of this scoping review can contribute to future research and clinical practice, and may inform the design and implementation of volunteer programmes for older adults in acute care services. To enhance the quality of evidence in this relevant field of study, we advise future intervention studies include control groups to allow direct comparison between volunteer‐assisted and standard care patients. Furthermore, we recommend future studies include comprehensive volunteer training protocols, well‐defined volunteer roles, single‐component interventions (volunteer assistance as the only exposure), consideration of patient acuity and the use of validated tools to measure cognitive impairment, physical function and nutritional intake.

8. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

The review findings enhance understanding of the impact of volunteers on health outcomes and may potentially inform decisions relating to the role of volunteers in supporting care delivery by nurses and other health professionals; design of volunteer programmes; and patient, staff and volunteer evaluation of volunteer care and support for older adults in acute care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design and concept, data acquisition and data analysis and interpretation; manuscript draft and critical revision for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: RS, KS, RG, AC. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Supporting information

Appendix 1: Database Searches

Saunders R, Seaman K, Graham R, Christiansen A. The effect of volunteers’ care and support on the health outcomes of older adults in acute care: A systematic scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:4236–4249. 10.1111/jocn.15041

REFERENCES

- Agency for Clinical Innovation (2019). Undertake cognitive screening: Screening patients. Retrieved from https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/chops/chops-key-principles/undertake-cognitive-screening/screening-patients [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government, Australia Institute of Health and Welfare (2018). Deaths in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-death/deaths/contents/life-expectancy [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017). Australia’s hospitals 2015–16 at a glance (Health Services Series No. 77. Cat. No. HSE 189). Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/d4e53b39-4718-4c81-ba90-b412236961c5/21032.pdf.aspx?inline=true [Google Scholar]

- Babudu, P. , Trevithick, E. , & Spath, R. (2016). Measuring the impact of helping in hospital: Final evaluation report. Retrieved from https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/helping_in_hospitals_evaluation_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Baczynska, A. M. , Lim, S. E. , Sayer, A. A. , & Roberts, H. C. (2016). The use of volunteers to help older medical patients mobilise in hospital: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(21–22), 3102–3112. 10.1111/jocn.13317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, C. , Anderson, K. , Bird, M. , & Hungerford, C. (2016). Volunteers improving person‐centred dementia and delirium care in a rural Australian hospital. Rural and Remote Health, 16(2), 3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H. , & Jones, L. (2009). The role of dining companions in supporting nursing care. Nursing Standard, 23(41), 40–46. 10.7748/ns2009.06.23.41.40.c7049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candy, B. , France, R. , Low, J. , & Sampson, L. (2015). Does involving volunteers in the provision of palliative care make a difference to patient and family wellbeing? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(3), 756–768. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, G. A. , & Harper, E. L. (2007). Recruitment of volunteers to improve vitality in the elderly: The REVIVE* study. Internal Medicine Journal, 37(2), 95–100. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalambous, L. (2014). The value of volunteers on older people's acute wards. Nursing times, 110(43), 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue, J. , Graham, J. , Mitten‐Lewis, S. , Murphy, M. , & Gibbs, J. (2005). A volunteer companion‐observer intervention reduces falls on an acute aged care ward. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 18(1), 24–31. 10.1108/09526860510576947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, D. , Carrier, J. , & Hopkinson, J. (2017). Assistance at mealtimes in hospital settings and rehabilitation units for patients (>65 years) from the perspective of patients, families and healthcare professionals: A mixed methods systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 69, 100–118. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G. , Mant, J. , Langhorne, P. , Dennis, M. , & Winner, S. (2010). Stroke liaison workers for stroke patients and carers: An individual patient data meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2010(5), 1-101. 10.1002/14651858.cd005066.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons, B. , Goodrich, J. , Bennett, L. , & Buck, D. (2014). Evaluation of King’s College Hospital volunteering service: Final report for KCH ‐ 23rd April 2014. Retrieved from https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/kings_fund_evaluation_of_kch_impact_volunteering.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Flicker, L. , & Holdsworth, K. (2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and dementia: A review of the research ‐ A report for Alzheimer’s Australia. (Paper 41). Retrieved from https://www.dementia.org.au/files/Alzheimers_Australia_Numbered_Publication_41.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Galea, A. , Naylor, C. , Buck, D. , & Weaks, L. (2013). Volunteering in acute trusts in England: Understanding the scale and impact. Retrieved from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/volunteering-in-acute-trusts-in-england-kingsfund-nov13.pdf [Google Scholar]

- George, J. , Long, S. , & Vincent, C. (2013). How can we keep patients with dementia safe in our acute hospitals? A review of challenges and solutions. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 106(9), 355–361. 10.1177/0141076813476497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles, L. C. , Bolch, D. , Rouvray, R. , McErlean, B. , Whitehead, C. H. , Phillips, P. A. , & Crotty, M. (2006). Can volunteer companions prevent falls among inpatients? A feasibility study using a pre‐post comparative design. BMC Geriatrics, 6(11), 1-7. 10.1186/1471-2318-6-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, S. , Piotrowicz, K. , Rewiuk, K. , Halicka, M. , Kalwak, W. , Rybak, P. , & Grodzicki, T. (2017). Nonpharmacological interventions targeted at delirium risk factors, delivered by trained volunteers (medical and psychology students), reduced need for antipsychotic medications and the length of hospital stay in aged patients admitted to an acute internal medicine ward: Pilot study. BioMed Research International, 2017, 1–8. 10.1155/2017/1297164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, S. M. , Martin, H. J. , Roberts, H. C. , & Sayer, A. A. (2011). A systematic review of the use of volunteers to improve mealtime care of adult patients or residents in institutional settings. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(13–14), 1810–1823. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C. L. , Brooke, J. , Pendlebury, S. T. , & Jackson, D. (2017). What is the impact of volunteers providing care and support for people with dementia in acute hospitals? A systematic review. Dementia, 18(4), 1410–1426. 10.1177/1471301217713325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horey, D. , Street, A. F. , O’Connor, M. , Peters, L. , & Lee, S. F. (2015). Training and supportive programs for palliative care volunteers in community settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(7), 1-31. 10.1002/14651858.CD009500.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hshieh, T. T. , Yang, T. , Gartaganis, S. L. , Yue, J. , & Inouye, S. K. (2018). Hospital Elder Life Program: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of effectiveness. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(10), 1015–1033. 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. S. , Dutkowski, K. , Fuller, A. , & Walton, K. (2015). Evaluation of a pilot volunteer feeding assistance program: Influences on the dietary intakes of elderly hospitalised patients and lessons learnt. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 19(2), 206–210. 10.1007/s12603-014-0529-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, C. E. , Dickens, A. P. , Jones, K. , Thompson‐Coon, J. O. , Taylor, R. S. , Rogers, M. , … Richards, S. H. (2013). Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 773 10.1186/1471-2458-13-773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. A. , Gibbs, N. E. , Fahey, L. , & Whiffen, T. L. (2013). Making hospitals safer for older adults: Updating quality metrics by understanding hospital‐acquired delirium and its link to falls. The Permanente Journal, 17(4), 32–36. 10.7812/tpp/13-065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), W‐65–W‐94. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C. , Porrit, K. , Munn, Z. , Rittenmeyer, L. , Salmond, S. , Bjerrum, M. , Stannard, D. (2017). Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence In Aromataris E., & Munn Z. (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. Adelaide, South Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, F. , Harris, K. , Duncan, R. , Walton, K. , Bracks, J. , Larby, L. , … Batterham, M. (2012). Additional feeding assistance improves the energy and protein intakes of hospitalised elderly patients. A Health Services Evaluation. Appetite, 59(2), 471–477. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudge, A. M. , Maussen, C. , Duncan, J. , & Denaro, C. P. (2013). Improving quality of delirium care in a general medical service with established interdisciplinary care: A controlled trial. Internal Medicine Journal, 43(3), 270–277. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, C. , Mundle, C. , Weaks, L. , & Buck, D. (2013). Volunteering in health and care: Securing a sustainable future. London: The King’s Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, H. C. , De Wet, S. , Porter, K. , Rood, G. , Diaper, N. , Robison, J. , … Robinson, S. (2014). The feasibility and acceptability of training volunteer mealtime assistants to help older acute hospital inpatients: The Southampton Mealtime Assistance Study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(21–22), 3240–3249. 10.1111/jocn.12573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, H. C. , Pilgrim, A. L. , Jameson, K. A. , Cooper, C. , Sayer, A. A. , & Robinson, S. (2017). The impact of trained volunteer mealtime assistants on the dietary intake of older female in‐patients: The Southampton Mealtime Assistance Study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 21(3), 320–328. 10.1007/s12603-016-0791-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S. , Clump, D. , Weitzel, T. , Henderson, L. , Lee, K. , Schwartz, C. , … Metz, L. (2002). The Memorial Meal Mates: A program to improve nutrition in hospitalized older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 23(6), 332–335. 10.1067/mgn.2002.130279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, F. H. , Neal, K. , Fenlon, K. , Hassan, S. , & Inouye, S. K. (2011). Sustainability and scalability of the Hospital Elder Life Program at a community hospital. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(2), 359–365. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03243.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, F. H. , Williams, J. T. , Lescisin, D. A. , Mook, W. J. , Hassan, S. , & Inouye, S. K. (2006). Replicating the Hospital Elder Life Program in a community hospital and demonstrating effectiveness using quality improvement methodology. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(6), 969–974. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawomirski, L. , Auraaen, A. , & Klazinga, N. (2017). The economics of patient safety: Strengthening a value‐based approach to reducing patient harm at national level. OECD Health Working Papers (No. 96). Paris: OECD Publishing; 10.1787/5a9858cd-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C. M. , Rivera, T. , Bernick, L. , & Mortensen, L. (2007). Insights regarding mealtime assistance for individuals in long‐term care. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 23(4), 319–329. 10.1097/01.tgr.0000299160.67740.44 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steunenberg, B. , van der Mast, R. , Strijbos, M. J. , Inouye, S. K. , & Schuurmans, M. J. (2016). How trained volunteers can improve the quality of hospital care for older patients. A qualitative evaluation within the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP). Geriatric Nursing, 37(6), 458–463. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strijbos, M. J. , Steunenberg, B. , van der Mast, R. C. , Inouye, S. K. , & Schuurmans, M. J. (2013). Design and methods of the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), a multicomponent targeted intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients: Efficacy and cost‐effectiveness in Dutch healthcare. BMC Geriatrics, 13, 78 10.1186/1471-2318-13-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone, E. C. , Tovey, J. A. , Paciepnik, J. E. , Keeton, I. M. , Khoo, A. Y. , Van Veenendaal, N. G. , & Porter, J. (2015). Should we implement mealtime assistance in the hospital setting? A systematic literature review with meta‐analyses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(19–20), 2710–2721. 10.1111/jocn.12913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie, E. , Zarin, W. , O'Brien, K. K. , Colquhoun, H. , Levac, D. , … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/m18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton, K. , Williams, P. , Bracks, J. , Zhang, Q. , Pond, L. , Smoothy, R. , … Vari, L. (2008). A volunteer feeding assistance program can improve dietary intakes of elderly patients: A pilot study. Appetite, 51(2), 244–248. 10.1016/j.appet.2008.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A. , Burford, S. , Wyles, C. L. , Mundy, H. , & Sainsbury, R. (2008). Evaluation of strategies to improve nutrition in people with dementia in an assessment unit. The Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging, 12(5), 309–312. 10.1007/bf02982660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L. , Cotter, D. , & Hickson, M. (2008). The effectiveness of targeted feeding assistance to improve the nutritional intake of elderly dysphagic patients in hospital. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 21(6), 555–562. 10.1111/j.1365-277x.2008.00915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Database Searches