Abstract

The bimetallic metal complex Titanocref exhibits relevant anticancer activity, but it is unknown if it is stable to reach target tissues intact. To gain insight, a pharmacologically relevant dose was added to human blood plasma and the mixture was incubated at 37°C. The obtained mixture was analyzed 5 and 60 min later by size-exclusion chromatography hyphenated to an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (SEC-ICP-AES). We simultaneously detected several titanium (Ti), gold (Au) and sulfur (S)-peaks, which corresponded to a Ti degradation product that eluted partially, and a Au degradation product that eluted entirely bound to plasma proteins (both time points). Although ~70% of the intact Titanocref was retained on the column after 60 min, our results allowed us to establish --for the first time --its likely degradation pathway in human plasma at near physiological conditions. These results suggest that ~70% of Titanocref remain in plasma after 60 min, which supports results from a recent in vivo study in which mice were treated with Titanocref and revealed Ti:Au molar ratios in tumors and organs close to 1:1. Thus, our stability studies suggest that the intact drug is able to reach target tissue. Overall, our results exemplify that SEC-ICP-AES enables the execution of intermediate in vitro studies with human plasma in the context of advancing bimetallic metal-based drugs to more costly clinical studies.

1. Introduction

Although the anticancer drug cisplatin is used to treat patients worldwide [1], this prototypical metal-based drug offers a limited spectrum of activity, its use is associated with the development of drug resistance and severe side-effects [2]. While many research efforts currently aim to improve the delivery of Pt-based drugs, there is still an urgent need to identify novel metal-based drugs that offer better selectivity and less off-target effects [3–7]. In addition to a recent resurgence of Pt-based drugs, non-conventional Pt-entities are also increasingly investigated as prospective cancer chemotherapeutics [8–10]. While the combination of two individual metal-based drugs (i.e. combination therapy) can be more effective than either drug alone [5], compounds which contain two metal centers (i.e. heterometallic metal complexes) are emerging as another attractive possibility to overcome drug resistance [11]. The bimetallic metal complex Titanocref (Fig. 1)[12–15] offers to hit cancer cells with two ‘war heads’, provided that the intact drug is taken up by cancer cells and disintegrates in the reducing environment of the cytosol into two cytotoxic metal-entities (i.e. ‘war heads’). Indeed, detailed in vivo efficacy trials were performed with Titanocref in Caki-1 xenografts in Nod.CB17-p rdkdc SCId/J mice [12, 13] and more recently optimized to include PK analysis and histopathology studies [15]. After a detailed pharmacokinetic efficacy trial revealed an optimal dosage of 5 mg/kg body wt every 72 h, the treatment of mice with Titanocref displayed an impressive tumor size reduction (51% after 21 days) and detailed histopathological studies showed a remarkable lack of systemic toxicity [15]. In addition, the Ti:Au molar ratio was 1.1:1 in the tumor, 1.1:1 in the kidneys and 1.3:1 in the liver 72 h after the efficacy trial had ended.

Figure 1.

Structure of Titanocref and proposed degradation pathway in human plasma to products I-V.

While Titanocref is soluble in DMSO:PBS (1:99) and inhibits renal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo, its half-life of 8 h in neat DMSO-d8 [12] demonstrates its vulnerability to degradation in this solvent. To gain insight into its stability at near physiological conditions in human plasma, a pharmacologically relevant dose of Titanocref was added to human plasma (152 μM) and the latter was analyzed after 5 and 60 min by SEC-ICP-AES [1].

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and solutions

Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) powder was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and DMSO (99.9%) from Fisher Chemicals (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). PBS–buffer was used as the mobile phase (pH 7.4). Titanocref and Cref (Fig. 1) were synthesized as previously reported and their purity assessed by 1H-NMR [12, 14]. A stock solution of Titanocref was prepared by dissolving 11.1 mg in 1.25 mL DMSO (~10 mM). A stock solution of Cref was prepared by dissolving 4.1 mg of this metallic complex in 610 μL of DMSO (~10 mM).

2.2. Instrumentation

The SEC-ICP-AES system was comprised of a 0.5 mL PEEK injection loop, a Superdex™ 200 Increase High Resolution SEC column (30.0 × 1.0 cm I.D., GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA; particle size: 8.6 μm; fractionation range ~600–10 kDa), and a Prodigy high-dispersion, radial-view ICP-AES (Teledyne Leeman Labs, Hudson, NH, USA) to simultaneously detect Au at 242.795 nm, Ti at 334.941 nm and S at 180.731 nm. A flow rate of 0.75 mL/min was used and the column was size-calibrated with a protein mixture as previously reported using carbon specific-detection (193.091 nm) and all other instrumental parameters and data analysis procedures were the same as previously reported [16].

2.3. Blood plasma

Blood was collected (healthy male volunteer) using trace metal grade blood collection tubes (ethics approval REB15–1138-REN5).

2.4. Titanocref and Cref in PBS-buffer

After dissolving a 25 μL aliquot of the Titanocref and Cref stock solution in 40 μL PBS-buffer, 1.8 mL of PBS-buffer were added and the obtained solution was incubated for 5 min at 37°C before it was analyzed by SEC-ICP-AES.

2.4. Titanocref and Cref in human plasma

2.0 mL of human plasma were thawed (45 min) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After dissolving 25 μL of a freshly prepared Titanocref or Cref stock solution in 40 μL PBS buffer, 1.8 mL of human plasma were added and the mixture was incubated at 37°C. Aliquots (750 μL) were withdrawn for analysis after 5 and 60 min, diluted with 250 μL of PBS buffer to reduce the viscosity and injected onto the SEC-ICP-AES system (triplicate analysis at each time point).

3. Results and Discussion

The analysis of Titanocref spiked PBS-buffer revealed that only 16.4% of the injected Ti eluted from the column in form of two major and two minor Ti-peaks, while no Au-peaks were detected (electronic supplementary information ESI-1, Table 1). These results imply that the intact Titanocref strongly binds to the stationary phase, most likely via the formation of hydrogen bonds between its C=O moiety and the OH-groups from the agarose/dextran-based stationary phase as has been previously reported for compounds with similar functional groups [17, 18]. A single major Ti-peak eluted past the inclusion volume, which corresponds to a Ti-containing degradation product (Fig. 1, II) that strongly interacted with the stationary phase. Titanocene compounds are known to hydrolyze quickly to produce species with water and hydroxo ligands and loss of the Cp rings [19, 20]. The fact that no Au-peak was detected (ESI-1), implies that Titanocref and the Au-containing degradation product Au(SC6H4COOH)PPh3 (Fig. 1, III/Cref) strongly bound to the stationary phase, likely due to the strong interaction of its COOH moiety with the OH-groups of the stationary phase. Previously, a Ti-Au degradation product species containing 4mercaptobenzoeic acid (4MBA) and one Cp have been identified in solutions of Titanocref in 1% DMSO:PBS-buffer mixtures after 24 h [12].

Table 1:

Total average mean area for the analysis of Titanocref in PBS buffer with or without column and the analysis of Titanocref in human plasma with column after 5- and 60-min incubation

| Titanium (Ti) | Gold (Au) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug in PBS without column | Drug in PBS with column | Drug in plasma with column | Drug in PBS without column | Drug in PBS with column | Drug in plasma with column | |||

| @ 5 min | @ 60 min | @ 5 min | @ 60 min | |||||

| (c/s) | 1680360 ± 17386 | 275403 (16.4%) | 139886 ± 1517 | 265295 ± 13655 | 248841± 5681 | N/D | 52083 ± 2267 | 72927± 2169 |

| Recovery in % | 16.4 | 8.3 | 15.5 | N/D | 21.0 | 29.3 | ||

N/D - not detected

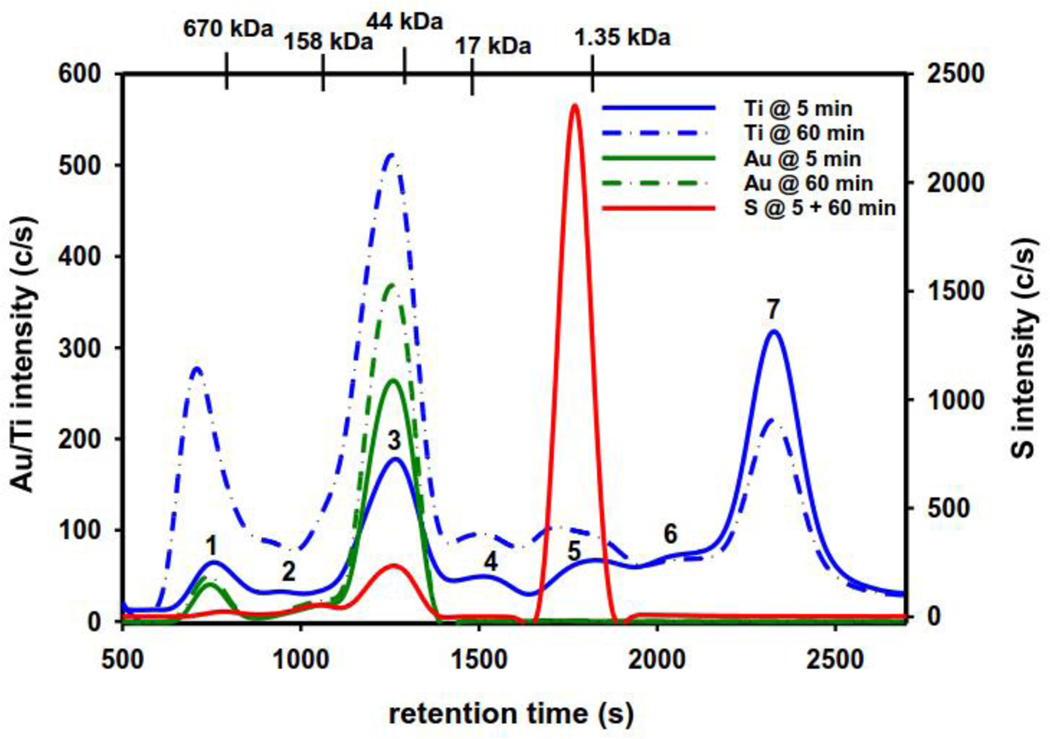

The addition of Titanocref to human plasma and subsequent analysis revealed that 8.3% of the injected Ti and 21.0 % of the injected Au eluted (5 min), while 15.5 % of the injected Ti and 29.3% of the injected Au eluted (60 min; Table 1). The strong binding of the intact bimetallic complex to the stationary phase even in the presence of the plasma matrix substantiates the results in PBS-buffer (ESI-1). In contrast, more Ti and Au-species eluted after Titanocref was incubated with human plasma (Fig. 2) and revealed three major and four minor Ti-peaks (5 and 60 min), as well as two major and one minor Au-peak. These results imply that Titanocref-derived Ti and Au-containing degradation products eluted bound to plasma proteins, while one major and one minor Ti-degradation product eluted past the inclusion volume. At the 5 min time point (Fig. 2), a minor Au-peak (11.7% of total Au, Table 2) and a minor Ti-peak (5.6% of total Ti, Table 2) eluted in the void volume, while the second minor Au-peak (8.0% of total Au) and the second Ti-peak (2.5% of total Ti) eluted shortly after the 670 kDa MW marker. The third, major Au-peak (80.4% of total Au) and the second major Ti-peak (23.6% of total Ti) co-eluted with a S-peak that corresponds to human serum albumin (HSA) since both peaks eluted just before the 44 kDa MW marker. The fact that the intensity of this S-peak was identical for both time points (Fig. 2, red solid line) and unspiked plasma (data not shown) implies that only Ti and Au-containing degradation products that did not contain S eluted bound to HSA. After the elution of three minor Ti-peaks (combined ~15% of total Ti), a major Ti-peak eluted (45.5% of total Ti), which was also observed in the PBS-buffer experiments (ESI-1). The S-specific chromatograms for Titanocref-spiked plasma (5 and 60 min) revealed an intense and sharp S-peak (Fig. 2, red solid line) that eluted in the inclusion volume and corresponds to DMSO (data not shown), which was used to dissolve Titanocref. To confirm if the S-peak that corresponds to DMSO may contain a possible S-containing degradation product of Titanocref underneath (Fig. 1b, V), the analysis of human plasma spiked with a 4mercaptobenzoeic acid (4MBA) standard indeed resulted in a S-peak which had the same retention time as DMSO (Fig. 3, red dotted line). The Ti and Au-specific chromatograms that were obtained at 60 min were qualitatively similar to those at 5 min. While an increased intensity of the plasma protein bound Ti and Au-peaks was expected after 60 min based on the ongoing degradation of Titanocref, the intensity of the Ti-degradation product that eluted past the inclusion volume actually decreased. This behavior is attributed either to the sluggish binding of the putative Ti-breakdown product, which lacks the Cp’s (Fig. 1, II)[12] to transferrin [21], HSA and the plasma protein that binds this Ti-degradation product which eluted in the void volume (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Representative SEC-ICP-AES derived Ti, Au and S-specific chromatograms that were obtained 5 min and 60 min after the incubation of a solution obtained by adding a pharmacologically relevant dose of Titanocref to human plasma (152 μM) at 37°C. Column: Superdex™ 200 Increase HR SEC column (30.0 × 1.0 cm I.D.), Flow rate: 0.75 ml/min, Injection volume: 500 μL. Detector: radial ICP-AES, simultaneous detection of Ti (334.941 nm), Au (242.795 nm) and S (180.731 nm). The retention times of the molecular weight calibration markers are depicted on top.

Table 2:

Average mean area for Ti and Au peaks after the analysis of Titanocref in human plasma with column after 5- and 60-min incubation.

| Titanium (Ti) | Gold (Au) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Retention time (s) |

Peak 1 754 ± 7 |

Peak 2 992 ± 81 |

Peak 3 1263 ± 3 |

Peak 4 15081 ± 4 |

Peak 5 1832 ± 3 |

Peak 6 21321 ± 0 |

Peak 7 23291 ± 1 |

Σ (mean areas) | Peak 1 743 ± 2 |

Peak 2 1084 ± 10 |

Peak 3 1251 ± 6 |

Σ (mean areas) |

| Mean area @ 5 min (c/s) | 7846 ± 1380 | 3521 ± 1412 | 32972 ± 520 | 6849 ± 90 | 14142 ± 189 | 10811 ± 413 | 63745 ± 1609 | 139886 ± 1517 | 6101 ± 287 | 4131 ± 599 | 41851 ± 1611 | 52083 ± 2267 |

| Mean % area | 5.6 | 2.5 | 23.6 | 5.0 | 10.1 | 7.7 | 45.5 | 100 | 11.7 | 8.0 | 80.4 | 100 |

| Mean area @ 60 min (c/s) | 43278 ± 1061 | 10595 ± 1201 | 110195 ± 5475 | 17918 ± 1751 | 29120 ± 1957 | 12467 ± 988 | 41722 ± 5420 | 265295 ± 13655 | 8728 ± 652 | 5270 ± 189 | 58929 ± 2305 | 72927 ± 2169 |

| Mean % area | 16.3 | 4.0 | 41.5 | 6.8 | 11.0 | 4.7 | 15.7 | 100 | 12.0 | 7.2 | 80.8 | 100 |

Figure 3.

Representative SEC-ICP-AES derived S-specific chromatograms that were obtained 5 min after the incubation of a solution obtained by adding a pharmacologically relevant dose of Titanocref to human plasma (152 μM) at 37°C (red solid line) and the addition of 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4MBA dissolved in DI water) to human plasma (red dashed line). Column: Superdex™ 200 Increase HR SEC column (30.0 × 1.0 cm I.D.), Flow rate: 0.75 ml/min, Injection volume: 500 μL. Detector: radial ICP-AES, detection of S (180.731 nm). The retention times of the molecular weight calibration markers are depicted on top.

The analysis of Cref spiked human plasma revealed essentially four Au-peaks and three S-peaks, which essentially remained unchanged in intensity between 5 and 60 min (ESI-2). While the first three Au-peaks eluted at similar retention times as the Titanocref-spiked human plasma, the additional Au-peak that was observed for Cref corresponds to intact Cref, which co-eluted with S in the inclusion volume (Fig. 2). Thus, the three Au-peaks that were observed when Titanocref was added to human plasma likely stem from the binding of the Cref degradation product Au(PPh3P)+ to HSA (Fig. 1, IV) and other plasma proteins by exchange of thiol groups. These results support the proposed degradation of Titanocref to Cref, which then degrades to IV and V (Fig. 1).

Based on these chromatographic results, we propose that Titanocref partially degrades to a bimetallic species (Fig. 1, I), which then degrades to products II-V (Fig. 1), with Cref (Fig 1, III) as an intermediate (ESI-2). While the proposed Ti-containing breakdown product II [19, 20] partially bound to transferrin [21] and/or HSA, the unbound fraction eluted past the inclusion volume (Fig. 2). The proposed Au(PPh3)+ degradation product predominantly bound to HSA at both time points (ESI-2) and the corresponding Au-peak intensity in human plasma increased at the 60 min time point (Fig. 2). Conversely, the proposed 4MBA degradation product could not be directly observed owing to its co-elution with DMSO (Fig. 3). Thus, ~70% of Titanocref remained intact in human plasma over the investigated time period (as indicated by its binding to the column) and the proposed formation of Au(HSA)(PPh3) may render Au(PPh3)+ pharmacologically active based on its structural similarity to [Au(PEt3)]+ [22–24].

4. Conclusion

Studies directed at investigating the stability of Titanocref in human plasma revealed that ~30% disintegrated to Ti and Au degradation products (the S-containing degradation product could not be observed) and that ~70% of the parent bimetallic complex remained intact after 60 min. Together with recent in vivo results which demonstrated that both Ti and Au are found in molar ratios of close to 1:1 in tumor and organs after the administration of mice with Titanocref [12–15], our results suggest that the intact bimetallic drug is able to reach the intended target tissue. Thus, our results demonstrate that advanced hyphenated analytical techniques [25] can be employed to gain important insight into the stability of bimetallic metal complexes that have potential as cancer chemotherapeutics [12–15, 26–28]. The inherent capability of this conceptually straightforward approach to rapidly screen the stability of potential bimetallic drug candidates in human plasma may help to accelerate the most promising ones to subsequent clinical studies [11, 29].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Titanocref is a bimetallic complex that exerts relevant anticancer activity

Little is known about its stability in human plasma at physiological conditions

A hyphenated analytical technique was used to probe its stability in human plasma

The detection of breakdown products allowed to establish its degradation pathway

Our results corroborate those from in vivo studies in a mouse model

Acknowledgements

SSK received a scholarship from Alberta Innovates Technology Futures (AITF). We thank Dr. Natalia Curado and Dr. Virginia del Solar for the preparation of Titanocref and Cref. The US National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) and gratefully acknowledged for grants 1SC1CA182844 and 2SC1GM127278–05A1 (M.C.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Author statement

MC provided Titanocref and Cref and helped with the interpretation of the results. JG and SSK conceptualized the study and wrote the manuscript. SSK executed all measurements.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Sooriyaarachchi M, Narendran A, Gailer J, Metallomics, vol. 3, 2011, pp. 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cheff DM, Hall MD, J. Med. Chem., vol. 60, 2017, pp. 4517–4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sooriyaarachchi M, George GN, Pickering IJ, Narendran A, Gailer J, Metallomics, vol. 8, 2016, pp. 1170–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Eljack ND, Ma H-YM, Drucker J, Shen C, Hambley TW, New EJ, Friedrich T, Clarke RJ, Metallomics, vol. 6, 2014, pp. 2126–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sooriyaarachchi M, Wedding JL, Harris HH, Gailer J, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem., vol. 19, 2014, pp. 1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Browning RJ, Reardon PJT, Parhizkar M, ACS Nano, vol. 11, 2017, pp. 8560–8578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].V. Casini A. A and Meier-Menches SM Metal-based Anticancer Agents, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Englinger B, Pirker C, Heffeter P, Terenzi A, Kowol CR, Keppler BK, Berger W, Chem. Rev., vol. 119, 2019, pp. 1519–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Monro S, Colon H, Yin H, Roque J, Konda P, Gujar S, Thummel RP, Lilge L, Cameron CG, McFarland SA, Chem. Rev., vol. 119, 2019, pp. 797–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].A.S. Sigel H; Freisinger E and Sigel RKO Metallo-drugs development and Action of Anticancer Agents, Vol. 18 Zurich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Curado N, Contel M, in: Casini A, Vessieres A, Meier-Menches SM (Eds.), Metal Based Anticancer Agents, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fernandez-Gallardo J, Elie BT, Sadhukha T, Prabha S, Sanau M, Rotenberg SA, Ramos JW, Contel M, Chem. Sci., vol. 6, 2015, pp. 5269–5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Elie BT, Fernandez-Gallardo J, Curado N, Cornejo MA, Ramos JW, Contel M, Eur. J. Med. Chem., vol. 161, 2019, pp. 310–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Contel M, Fernandez-Gallardo J, Elie BT, Ramos JW, US Patent 9,315,531 (April/19/2016).

- [15].Elie BT, Hubbard K, Layek B, Yang WS, Prabha S, Ramos JW, Contel M, ACS Pharmacology Transl. Sci., vol. submitted, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gibson MA, Sarpong-Kumankomah S, Nehzati S, George GN, Gailer J, Metallomics, vol. 9, 2017, pp. 1060–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lommerse JPM, Price SL, Taylor R, J. Comput. Chem., vol. 18, 1997, pp. 757–774. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Withers SG, Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 44, 2001, pp. 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chen X, Zhou L, J. Mol. Struct. Theochem., vol. 940, 2010, pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang H, Lin H, Long Y, Ni B, He T, Zhang SB, Zhu H, Wang X, Nanoscale, vol. 9, 2017, pp. 20742081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Buettner KM, Valentine AM, Chem. Rev., vol. 112, 2011, pp. 1863–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dean TC, Yang M, Liu M, Grayson JM, Day CS, Lee JH, Furdui CM, Bierbach U, ACS Med. Chem. Lett. , vol. 8, 2017, pp. 572–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Marzo T, Massai L, Pratesi A, Stefanini M, Cirri D, Magherini F, Becatti M, Landini I, Nobili S, Mini E, Crociani O, Arcangeli A, Pillozzi S, Gambeir T, Messori L, ACS Med. Chem. Lett., vol. 10, 2019, pp. 656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Marzo T, Cirri D, Gabbiani C, Gamberi T, Magherini F, Pratesi A, Guerri A, Biver T, Binacchi F, Stefanini M, Arcangeli A, Messori L, ACS Med. Chem. Lett., vol. 8, 2017, pp. 997–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sooriyaarachchi M, Morris TT, Gailer J, Drug Discov Today: Technol, vol. 16, 2015, pp. e24–e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fernandez-Gallardo J, Elie BT, Sanau M, Contel M, Chem. Commun., vol. 52, 2016, pp. 3155–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Elie BT, Hubbard K, Pechenyy Y, Layek B, Prabha S, Contel M, Cancer Med., vol. 8, 2019, pp. 43044314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Elie BT, Pechenyy Y, Uddin F, Contel M, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem., vol. 23, 2018, pp. 399–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mjos KD, Orvig C, Chem. Rev., vol. 114, 2014, pp. 4540–4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.