Abstract

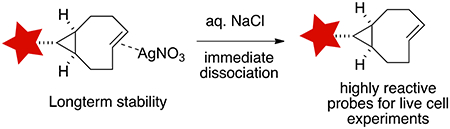

Conformationally strained trans-cyclooctenes (TCOs) engage in bioorthogonal reactions with tetrazines with second order rate constants that can exceed 106 M−1s−1. The goal of this study was to provide insight into the stability of TCO reagents and to develop methods for stabilizing TCO reagents for long-term storage. The radical inhibitor Trolox suppresses TCO isomerization under high thiol concentrations and TCO shelf-life can be greatly extended by protecting them as stable Ag(I) metal complexes. 1H NMR studies show that Ag-complexation is thermodynamically favorable but the kinetics of dissociation are very rapid, and TCO•AgNO3 complexes are immediately dissociated upon addition of NaCl which is present in high concentration in cell media. The AgNO3 complex of a highly reactive s-TCO-TAMRA conjugate was shown to label a protein-tetrazine conjugate in live cells with faster kinetics and similar labeling yield relative to a ‘traditional’ TCO-TAMRA conjugate.

Keywords: bioorthogonal chemistry, trans-cyclooctene, stability, radical inhibitor, silver complexation, cellular labeling

Graphical Abstract:

Introduction

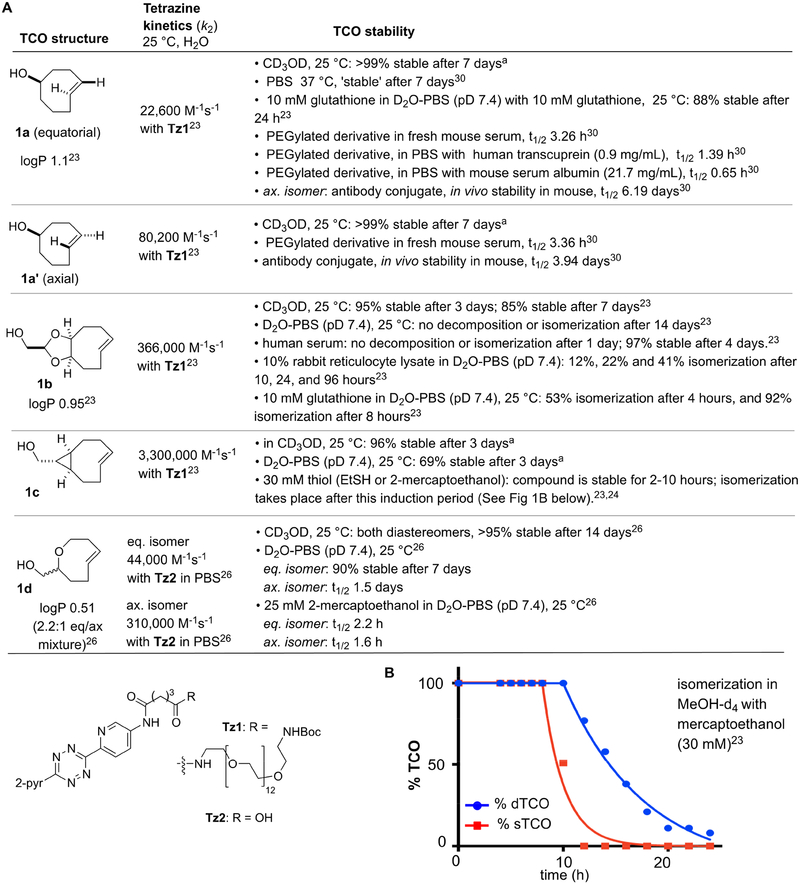

For nearly two decades, bioorthogonal chemistry has been employed for a broad range of applications spanning biomedicine and biotechnology. Tetrazine ligation— the cycloaddition of alkenes/alkynes and s-tetrazines—is a uniquely fast bioorthogonal reaction first developed in 2008 using trans-cyclooctene (TCO)1 and norbornene dienophiles.2 Tetrazine ligation since has become a broadly used tool for chemical biology, chemoproteomics, radiochemistry, and materials science.3–12 A complementary set of dienophiles for tetrazine ligation has been developed that includes cyclopropenes, cyclobutenes, cyclooctynes and simple α-olefins.13–22 However, trans-cyclooctene still maintains the advantage of exceptional reaction kinetics in this process, with reaction rates that exceed 104 M−1s−1 with parent TCO compounds.1,23 The conformationally strained trans cyclooctenes d-TCO (1b) and s-TCO (1c) display even faster reactivity, and participate in extremely rapid bioorthogonal reactions with tetrazines with rates exceeding 106 M−1s−1.23,24 Recently, trans-oxocenes were introduced as dienophiles with improved aqueous solubility that maintain high reactivity due to the short C-O bond in the backbone.25,26

To choose the best chemical tool for a biological interrogation, it is important to understand the relative rates of the bioorthogonal reaction as well as the rates of competing side reactions. For some bioorthogonal reagents, side reactions are biomolecular and can result in non-selective background labeling. By contrast, the primary mechanism for the deactivation of TCO reagents is isomerization to the cis-isomer. For cellular applications, isomerization decreases labeling efficiency but has the merit of not resulting in non-selective off-target labeling.1,23,24,26 Scheme 1 summarizes data from the literature, as well as newly collected data on the kinetic, stability and solubility characteristics of a series of trans-cyclooctene analogs. In the tetrazine ligation with Tz1 or the closely related Tz2, d-TCO (1b), s-TCO (1c) and oxoTCO (1d) possess kinetic advantages over the parent TCO compound 1a, but are also more prone to isomerization upon extended exposure to aqueous thiol concentrations that mimic the cellular environment.23,24,26 Due to their propensity to isomerize, the more reactive TCOs 1b-1d have greatest utility as probes for live cell applications, where only brief incubation in the cell is required due to the fast kinetics of the reaction. The use of TCOs as chemical reporters, which requires long-term stability in the cell, generally requires use of more resilient parent TCOs such as 1a. An additional, practical consideration for strained TCO derivatives of 1b-d is that they can be prone to deactivation upon long-term storage. While crystalline derivatives can be stored as solids over long periods (>1 year) in the refrigerator, non-solids must be stored as dilute solutions in the freezer and generally should be used within several weeks of preparation.

Scheme 1.

(A) Kinetic and stability properties of trans-cyclooctene derivatives under varied conditions. (B) Isomerization kinetics of s-TCO and d-TCO in MeOH containing mercaptoethanol.

a Data collected in this study.

Results and Discussion

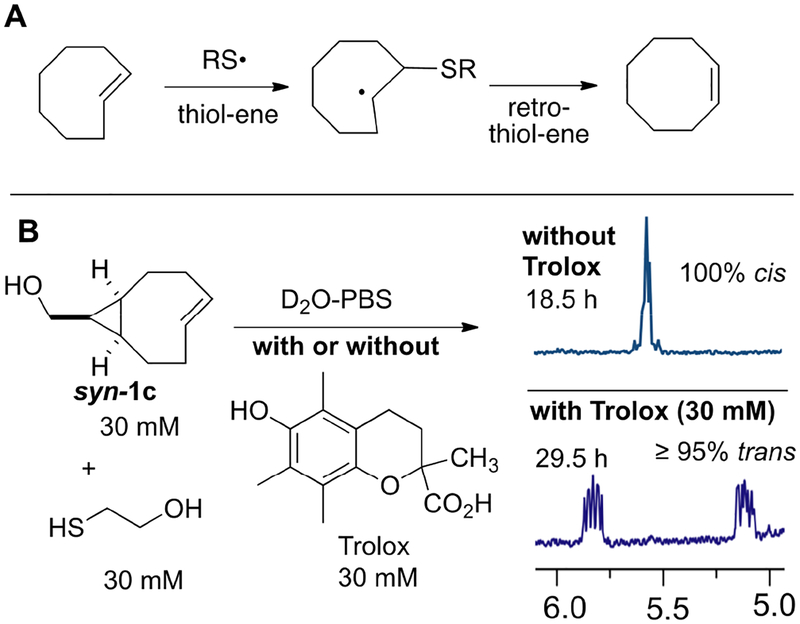

We have described previously that the isomerization of trans-cyclooctenes is promoted by high concentrations of thiols.1,23,24,26 Thiol-promoted isomerization is observed across all of the TCOs 1a-d, and in some cases is characterized by a long induction time before isomerization commences.23 For example, we previously noted that solutions of d-TCO 1b and s-TCO 1c were stable in CD3OD containing 30 mM mercaptoethanol for 12 and 8 hours, respectively, but subsequently underwent rapid isomerization (Scheme 1B).23 It was hypothesized that the isomerization of d-TCO and s-TCO may be a radical catalyzed reaction, and at high thiol concentrations the reaction may be promoted by a thiol-ene/retro thiol-ene pathway (Scheme 2A).27 A radical mechanism would be consistent with the unusual kinetic profile and induction period. During the induction period, the dissolved oxygen concentration is likely depleted through disulfide formation, and below a critical oxygen concentration the isomerization pathway would be favored. Radical intermediates have also been proposed to play an important role to the isomerization of trans-cycloheptenes through an ‘interrupted dimerization’ mechanism that follows second order kinetic behavior,28,29 and may also explain the higher propensity of trans-cyclooctenes to isomerize or degrade as neat materials. Robillard and coworkers have demonstrated that Cu-containing proteins can promote TCO isomerization.30 Cu-containing proteins are well known to engage in one-electron redox chemistry,31 again suggesting the possible involvement of radical pathway for the isomerization of TCO.

Scheme 2.

(A) Plausible mechanism for the thiol-promoted isomerization of trans-cyclooctenes. (B) Isomerization of syn-1c is promoted by mercaptoethanol and inhibited by Trolox, a water soluble vitamin E analog.

The goal of this study was to provide additional evidence for radical intermediates in TCO isomerization and to develop methods for stabilizing TCO reagents for long-term storage. Initially, we sought to test if radical inhibitors could be used to suppress trans-cycloooctene isomerization under high thiol concentrations where isomerization is normally rapid. In a control experiment, a 30 mM solution of the syn-diastereomer of s-TCO (syn-1c) and 30 mM mercaptoethanol were mixed in D2O-PBS (pD 7.4) and isomerization was monitored by 1H NMR after 1, 2, 4.5 and 18.5 hours, at which points 18%, 34%, 55% and 100% of the cis-isomer was detected, respectively. This isomerization was completely suppressed in a similar study where the radical inhibitor Trolox32 – a water-soluble analog of vitamin E – was included in the mixture. Thus, treatment of syn-1c with 30 mM mercaptoethanol and 30 mM Trolox in D2O-PBS led to <5% isomerization (NMR detection limit) after 29.5 h (Scheme 2B and Fig S4). Similar observations were observed in isomerization studies of syn-1c in methanolic solutions containing BHT, a radical inhibitor that has been used to stabilize TCO.33 Thus, complete isomerization was observed after 63 hours for a solution of 30 mM syn-1c in methanol containing 30 mM mercaptoethanol, whereas no isomerization was observed for a solution of 30 mM syn-1c and 30 mM mercaptoethanol containing 30 mM BHT (Fig S6). In the presence of low concentrations of a radical inhibitor, an induction period was observed prior to olefin isomerization. Thus, for 30 mM syn-1c in D2O-PBS in the presence of 30 mM mercaptoethanol and 1 mM Trolox, <5% isomerization was observed after 6.5 hours, but 52% isomerization was observed after 21 hours (Fig S5). Taken together, these observations that thiols promote isomerization, that high concentrations of Trolox inhibit isomerization in the presence of thiol, and that an induction period is seen at low concentrations of Trolox all provide support for a radical based pathway for TCO-isomerization in the presence of thiols. Given the high intracellular concentrations of thiols and the role of thiols in cellular redox regulation,34 it is also plausible that intracellular mechanisms for the deactivation of trans-cyclooctenes involve radical pathways.

Previously, we described that the shelf-life of conformationally strained trans-cycloalkene derivatives could be enhanced by protecting them as Ag(I) metal complexes, and that the free trans-cycloalkenes could be liberated by treatment with aq. NaCl or in cell media.35 Metal complexation was shown to be essential for the handling of sila-trans-cycloheptene complexes,29,36 which upon metal decomplexation participate in the fastest bioorthogonal reactions studied to date. Additionally, trans-cycloalkene AgNO3 complexes possess high water solubility relative to the free alkenes, which can provide advantages for biological experiments. A goal of the present study was to establish the generality of Ag(I) complexation for the stabilization across a series of trans-cyclooctene derivatives. It is shown that Ag(I) metal complexation by trans-cyclooctenes is thermodynamically favorable but kinetically reversible, and that Ag(I) exchange between TCO ligands is rapid on the NMR timescale at low temperature. NMR studies also show that the kinetics of NaCl-mediated decomplexation are very rapid. Finally, it is shown that a s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 complex rapidly labels a protein-tetrazine conjugate in live cells with yields that are similar to a TAMRA-TCO conjugate but with rates that are significantly faster.

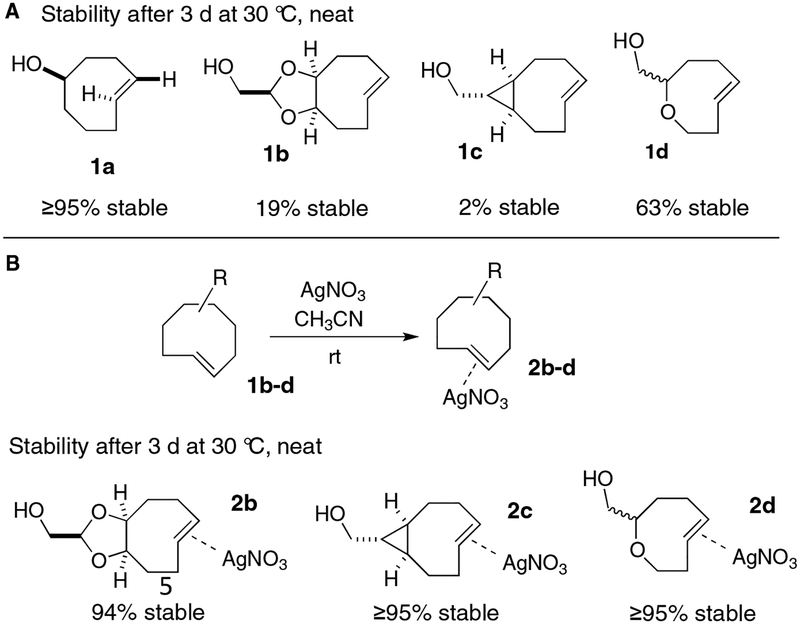

Shown in Scheme 3 is the comparison of the stabilities for a series of Ag-free TCO complexes and their AgNO3 complexes after storage in an open flask for 3 days at 30 °C. By 1H NMR analysis, the equatorial diastereomer 1a is stable under these conditions, whereas the more reactive trans-cycloalkenes d-TCO 1b, s-TCO 1c and oxoTCO 1d lead to 81%, 98% and 37% degradation. We note that these TCOs are much more stable in solution (Scheme 1), especially when stored in the freezer. For neat materials, undefined degradation products are formed, whereas olefin isomerization is observed in solution.

Scheme 3.

Stability comparisons for non-crystalline trans-cyclooctene derivatives when stored neat at 30 °C.

The preparation of trans-cyclooctene silver nitrate complex derivatives is straightforward and involves simply combining the TCO with AgNO3 in acetonitrile or methanol for 15 min, followed by concentration under reduced pressure. When neat s-TCO•AgNO3 (2c) was stored in an open flask at 30 °C for 3 days, the sample maintained ≥95% purity as determined by 1H NMR with an internal standard. We also studied the stability of complex 2c in methanol-d4 and DMSO-d6. After 3 days at 30 °C, the samples were still ≥95% pure. With d-TCO•AgNO3 (2b), there was 94% fidelity for a neat sample that was stored in the open for 3 days at 30 °C, while in methanol and DMSO, d-TCO•AgNO3 had 95% and 94% fidelity after 3 days at 30 °C respectively. oxoTCO•AgNO3 (2d) showed ≥95% stability when stored neat at 30 °C for 3 days. In the freezer, the TCO•AgNO3 complexes can be stored neat or in solution for >1 month without degradation.

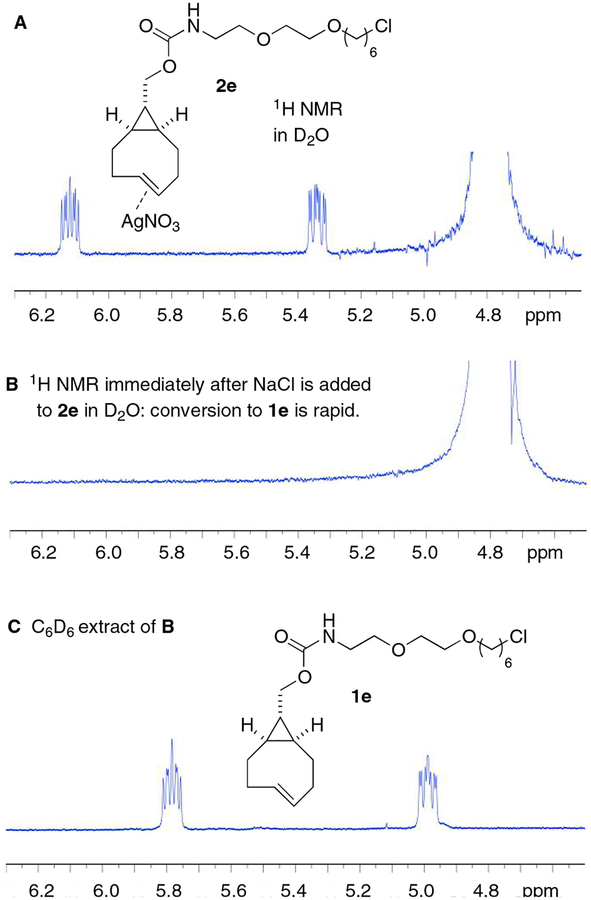

We next conducted an NMR experiment that demonstrates that dissociation of a trans-cyclooctene silver complex by NaCl is very rapid (Scheme 4). Here, compound 2e (5 mg) was dissolved in D2O (0.9 mL), followed by the addition of NaCl in D2O (0.1 mL, 100 mM). Within 3 minutes, the 1H NMR was remeasured, and no signal was observed. Upon extraction with C6D6, silver free 1e was recovered and observed by 1H NMR (Scheme 4). The experiment indicated that silver decomplexation of 2e was complete by the time an 1H NMR spectrum could be recorded.

Scheme 4.

NaCl decomplexation experiment

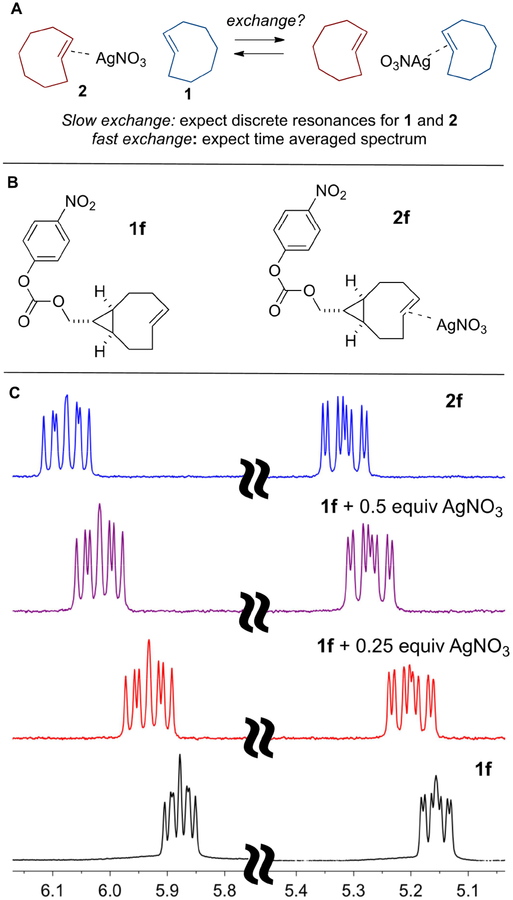

1H NMR spectroscopy was also used to study the kinetics and reversibility of Ag(I) coordination by TCO ligands. Previous x-ray crystallography studies of trans-cycloalkene silver complexes show that the alkene coordinates to the metal with 1:1 stoichiometry.29,37 We queried whether the exchange of a TCO ligand 1 with a TCO•AgNO3 complex 2 would be slow enough to observe by 1H NMR spectroscopy. If exchange is slow on the NMR timescale, discrete resonances would be expected for metal complex 2 and free alkene 1, whereas rapid exchange would lead to a time averaged spectrum of 1 and 2 (Scheme 5A). Combining TCO 1f with 1 equivalent AgNO3 to give metal complex 2f was accompanied by downfield shifts for the alkene resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum. Adding additional (0.5 equivalent) AgNO3 did not lead to further change in the NMR spectrum, consistent with 1:1 metal:alkene stoichiometry for the solution complex. As shown in Scheme 5, when fewer than 1.0 equivalent of AgNO3 was added to alkene 1f, time averaged NMR spectra were observed with a downfield shift proportional to the amount of AgNO3 that was added. Thus, for the alkene peak at 5.87 ppm, the addition of 0.25 and 0.5 equivalent of AgNO3 caused downfield shifts of ~0.06 and 0.12 ppm, respectively. The 1H NMR of 1f with 0.5 equivalent of AgNO3was also studied by VT-NMR down to −60 °C, and coalescence was not observed, indicating that exchange remains rapid on the NMR timescale at this temperature. Thus, while Ag-complexation is thermodynamically favorable for trans-cyclooctene, the complexes are labile in aqueous NaCl and the kinetics of dissociation are very rapid. Similar experiments were also carried out with the AgNO3 complex of 1a (Fig S8–9). For a 2:1 mixture of 1a: AgNO3, ligand exchange is rapid on the 1H NMR timescale at room temperature, but the NMR spectrum is broadened at −60 °C suggesting a faster rate of exchange for this less strained TCO.

Scheme 5.

(A) Schematic depiction of metal exchange between TCO ligands and study by 1H NMR spectroscopy. (B) Structures of TCO 1f and TCO•AgNO3 2f used for ligand exchange study. (C–F) 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) spectra of alkene regions of (F) 1f, (C) 2f, and mixtures obtained by mixing 1f with (E) 0.25 equiv AgNO3 or (D) 0.5 equiv AgNO3.

The high reactivity of conformationally strained trans-cycloalkenes make them useful probe compounds for applications where brief incubation in the cellular environment is required.29,35,38 In a previous study, the HaloTag protein-labeling platform was used to compare the rates and yields of various bioorthogonal reactions in live cells.35 Here, we surveyed a range of different HaloTag ligands containing bioorthogonal tags, including 3-methyl-6-phenyl-s-tetrazine. Pulse-chase experiments with a TAMRA-labeled chloroalkane control (TAMRA-Halo) showed that a similar percentage of incorporation was observed after a 30 min incubation for all of the HaloTag ligands in that series (70–79%), allowing for subsequent comparisons that would reflect differences in the labeling efficiency.

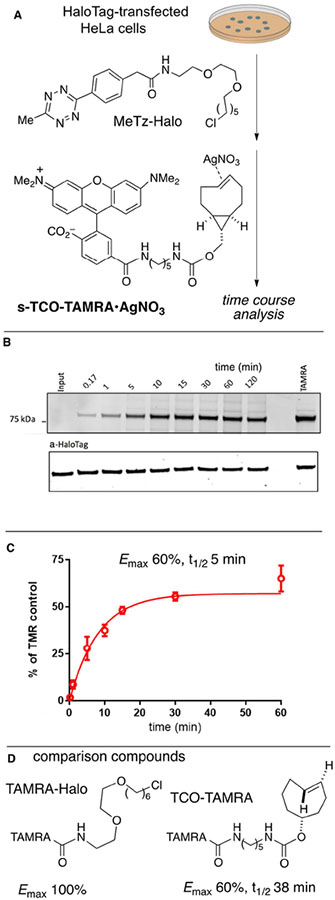

We also utilized silver complexes of s-TCO and d-TCO HaloTag conjugates to tag proteins with subsequent time course labeling by fluorescent tetrazine derivatives.35 Here, labeling efficiency decreases after prolonged cellular incubation, presumably due to TCO inactivation. We expected that reversing the tag and probe and use of a fluorescent s-TCO conjugate would enable more efficient labeling. To this end, an s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 conjugate was prepared by mixing s-TCO-TAMRA with silver nitrate. Metal complexation resulted in a characteristic downfield shift of the alkene peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum, and it was confirmed that mixing s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 with aq. NaCl rapidly resulted in metal decomplexation to regenerate s-TCO-TAMRA (Fig S2). Our previously reported haloalkane dehalogenase “HaloTag”-based platform was used to study the tetrazine ligation in live cells using s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3. In a cellular co-localization experiment, it was first confirmed that the TAMRA signal co-localizes with HaloTag-H2B-GFP fluorescence when live HeLa cells were labeled with 500 nM of s-TCO-TAMRA (Figure S7). To study the kinetics of labeling, HaloTag-transfected HeLa cells were then treated with MeTz-Halo (10 μM), washed and then treated with s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 (2 μM) for different incubation times up to 60 min (Scheme 6). Both the concentration and exposure time of AgNO3 to live cells are much lower than that used in cytotoxicity studies on HeLa cells (IC50 = 50 μM after 72 h).41 The tetrazine attached to HaloTag-H2B-GFP was quenched at the various time points by chasing with excess non-fluorescent TCO and in-gel fluorescence was used to quantify conversion vs. time. The labeling efficiency of s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 was compared to a TAMRA-labeled chloroalkane control (TAMRA-Halo, Promega Corporation) that was directly incorporated into HaloTag-H2B-GFP transfected HeLa cells, and also to two-step labeling with MeTz-Halo and TCO-TAMRA cells (Scheme 6D).

Scheme 6.

(A) Incorporation of MeTz-Halo into HaloTag-transfected HeLa cells, followed by labeling with s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 (2 μM). (B,C) Kinetics of labeling were evaluated by timecourse quenching with a non-fluorescent TCO with subsequent analysis by in-gel fluorescence. (D) The degree of labeling was benchmarked against cells in which TAMRA-Halo was directly incorporated, and cells in which MeTz-Halo incorporation was followed by labeling with TCO-TAMRA.

As shown in Scheme 6B,C, saturation was reached rapidly with a labeling t1/2 of 5 min and with 60% of the fluorescence intensity obtained with TAMRA-Halo.35 The maximum fluorescence of the two-step procedures involving tetrazine ligation was 60% of that obtained when TAMRA-Halo was directly incorporated. The lower labeling yields for the two-step procedures is partly due to a lower incorporation yield with MeTz-Halo relative to TAMRA-Halo35 and may be partly due to inactivation of MeTz in the intracellular environment. As shown in Scheme 6, the 60% relative fluorescence with s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 (3) was similar to that observed when a TAMRA conjugate of 5-hydroxy-trans-cyclooctene (TCO-TAMRA, Scheme 6D) was used,35 but the time to reach saturation was much slower (t1/2 = 38 min) with the 5-hydroxy-trans-cyclooctene conjugate.

Conclusions

In summary, this study shows how the lifetime of conformationally strained trans-cyclooctenes can be extended through the addition of radical inhibitors or through silver (I) metal complexation. The radical inhibitor Trolox is shown to suppress trans-cycloooctene isomerization under high thiol concentrations where isomerization is normally rapid, thereby providing support for a radical-mediated mechanism for TCO-isomerization. Additionally, the shelf-life of conformationally strained trans-cyclooctenes can be greatly extended by protecting them as stable Ag(I) metal complexes. VT-NMR studies show that Ag-complexation is thermodynamically favorable for trans-cyclooctene, but the complexes are labile and the kinetics of dissociation are very rapid. Further NMR studies show that TCO•AgNO3 complexes are immediately dissociated upon addition of NaCl. Thus, the most highly strained trans-cyclooctenes can be stabilized for long term storage through Ag(I) complexation, and then liberated on demand by addition of NaCl which is present in high concentration in cell media. To illustrate the utility of silver complexation in cellular labeling experiments, the silver nitrate complex of a highly reactive s-TCO-TAMRA conjugate was prepared, and was shown to label a protein-tetrazine conjugate in live cells with faster kinetics and similar labeling yield relative to an ‘ordinary’ TCO-TAMRA conjugate.

Experimental

General considerations.

Anhydrous methylene chloride was dried through a column of alumina using a solvent purification system. Anhydrous THF was freshly distilled from Na/benzophenone ketyl. All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Chromatography was performed on normal-phase silica gel from Silicycle (40–63 μm, 230–400 mesh). Reverse phase chromatography was performed on Teledyne Isco (Combiflash® RF). Conversions of photoisomerization reactions were monitored by GC (GC-2010 Plus, Shimadzu). APT and CPD pulse sequences were used for 13C NMR. When the APT pulse sequence was used for 13C NMR, the secondary and quaternary carbons were phased to appear ‘up’ (u), and tertiary and primary carbons appear ‘down’ (dn). Data are represented as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (br = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, dd = doublet of doublets). High resolution mass spectral data were taken with a Waters GCT Premier high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometer, or using a Thermo Q-Exactive Orbitrap instrument. Infrared (IR) spectra of compound 2c was obtained using FTIR spectrophotometers with films cast onto AgCl plate. Infrared (IR) spectra for compound 2c, 2b, 2f were collected from Bruker Tensor 27 and Nexus™ 670 FT-IR. ((1R,8S,9r,E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (s-TCO)24, ((1R,8S,9r,E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methyl (4-nitrophenyl) carbonate (s-TCO-NO2)24, ((2r,3aR,9aS,E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol (d-TCO)23, ((1R,8S,9s,E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methyl (2-(2-((6-chlorohexyl)oxy)ethoxy)ethyl)carbamate•AgNO343, (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol26 (oxoTCO) and 5-((3-aminopropyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-(dimethylamino)-3-(dimethyliminio)-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate39 were prepared following known procedures.

Synthesis of trans-Cyclooctene Silver Nitrate Complex Derivatives

((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (s-TCO•AgNO3) (2c).

To a flask containing ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (16.1 mg, 0.106 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added an acetonitrile (1.91 ml, 10.3 mg/ml) solution of silver nitrate (19.8 mg, 0.116 mmol, 1.10 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford (37.6 mg, quantitative yield) as white semisolid.1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 6.10–6.03 (m, 1H), 5.28 (ddd, J =16.6, 10.6, 3.5Hz, 1H), 3.49–3.41 (m, 2H), 2.55–2.44 (m, 2H), 2.35–2.29 (m, 1H), 2.25–2.20 (m, 2H), 1.98–1.88 (m, 1H), 1.08–0.97 (m, 1H), 0.87–0.77 (m, 1H), 0.67–0.60 (m, 1H), 0.49–0.41(m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 126.2 (dn), 118.8 (dn), 66.9 (u), 38.7 (u), 35.2 (u), 33.0 (u), 29.26 (dn), 29.25 (u), 22.2 (dn), 20.7 (dn); FTIR (ATR) 3436, 3003, 2978, 2914, 2850, 1572, 1448, 1385, 1300, 1111, 1076, 1041, 1014, 985, 928, 891, 843 cm−1; HRMS (CI+) m/z: [M-AgNO +H]+ calcd. for C10H17O+ 153.1274, found 153.1272.

((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (d-TCO•AgNO3) (2b).

To a flask containing ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol (15.6 mg, 0.0847 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added an acetonitrile (1.53 ml, 10.3 mg/ml) solution of silver nitrate (15.8 mg, 0.0931 mmol, 1.10 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford (33.8 mg, quantitative yield) as white semisolid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3CN) δ: 5.71–5.57 (m, 2H), 4.71 (t, J =3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (d, J =9.9 Hz, 2H), 3.48–3.42 (m, 2H), 3.39–3.26 (m, 1H), 2.38–2.35 (m, 1H), 2.33–2.28 (m, 1H), 2.12–2.05 (m, 3H), 1.76–1.56 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD OD) d: FTIR (ATR) 3395, 2934, 2866, 1576, 1396, 1140, 1034, 997, 903, 856, 818 cm−1; HRMS (CI+) m/z: [M-AgNO3+H]+ calcd. for C10H17O3+185.1172, found 185.1179.

(E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (oxoTCO•AgNO3) (2d).

To a flask containing (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol (11.6 mg, 0.0816 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added an acetonitrile (89.7 μL, 1.0 M) solution of silver nitrate (15.2 mg, 0.0897 mmol, 1.10 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 hour. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (28.0 mg, quantitative yield) as colorless semisolid.

Peaks due to major diastereomer:

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 5.87 (ddd, J = 15.8, 11.4, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 5.57 (ddd, J = 15.7, 11.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.14–4.09 (m, 1H), 3.48–3.41 (m, 3H), 3.14–3.08 (m, 1H), 2.72–2.67 (m, 1H), 2.54–2.49 (m, 1H), 2.31–2.13 (m, 2H), 2.02–1.81 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 129.4 (dn), 114.8 (dn), 86.7 (dn), 74.5 (u), 66.3 (u), 39.3 (u), 38.3 (u), 35.1 (u);

Peaks due to minor diastereomer:

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 6.05–5.97 (m, 1H), 5.55–5.51 (m, 1H), 3.91–3.85 (m, 1H), 3.84–3.79 (m, 2H), 3.68–3.62 (m, 1H), 3.47–3.42 (m, 1H), 2.56–2.50 (m, 1H), 2.45–2.44 (m, 2H), 2.31–2.13 (m, 1H), 2.01–1.83 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 126.7 (dn), 117.3 (dn), 81.9 (dn), 68.8 (u), 64.2 (u), 39.5 (u), 36.6 (u), 30.0 (u); FTIR (AgCl film) 3408, 3006, 2942, 2840, 1658, 1607, 1482, 1302, 1210, 1197, 1159, 1096, 1063, 1035, 944, 883 cm−1; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M+H-AgNO3]+ calcd. for C8H15O2 + 143.1067, found 143.1067.

((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methyl (4-nitrophenyl) carbonate•AgNO3 (2f).

To a flask containing ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methyl (4-nitrophenyl) carbonate (31.7 mg, 0.0999 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added an acetonitrile (0.813 ml, 22.96 mg/ml) solution of silver nitrate (18.7 mg, 1.10 mmol, 1.10 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 hour. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford (51.5 mg, quantitative yield) as white semisolid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ: 8.31 (d, J =9.1 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.07 (ddd, J =16.5, 8.9, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (ddd, J =16.5, 10.6, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.23–4.18 (m, 2H), 2.57–2.54 (m, 1H), 2.51–2.47 (m, 1H), 2.36–2.33 (m, 1H), 2.30–2.22 (m, 2H), 2.00–1.93 (m, 1H), 1.12–1.05 (m, 1H), 0.92–0.82 (m, 2H), 0.72–0.64 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150MHz, CD3OD) δ: 157.2 (u), 154.1 (u), 146.8 (u), 126.2 (dn), 125.8 (dn), 123.2 (dn), 118.7 (dn), 74.5 (u), 38.5(u), 35.0 (u), 32.8 (u), 29.1 (u), 25.5 (dn), 22.9 (dn), 21.4 (dn); FTIR (ATR) 2961, 2935, 1754, 1592,1513, 1442, 1344, 1271, 1248, 1206, 1113, 1008, 922, 846, 750 cm−1; HRMS (CI+) m/z: [M-AgNO +H]+ calcd. for C 17H20NO5 +318.1336, found 318.1347.

5-((3-(((((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)propyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-(dimethylamino)-3-(dimethyliminio)-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate (s-TCO-TAMRA).

To a DMSO (0.200 ml, anhydrous) solution of 5-((3-aminopropyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-(dimethylamino)-3-(dimethyliminio)-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate TFA salt (10.0 mg, 0.0166 mmol, 1.00 equiv) and N, N-Diisopropylethylamine (8.68μL, 0.0498 mmol, 3.00 equiv) was added ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methyl (4-nitrophenyl) carbonate (6.34 mg, 0.0199 mmol, 1.20 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 hour. The mixture was directly loaded onto C18 column (Universal ™ Column, Yamazen Corporation, Cat.No. UW112, 14g) using minimal amount of acetonitrile followed by H2O. The purification was performed by Teledyne Isco (Combiflash® RF), mobile phase A: 0.03% NH3▪H2O in water (v/v), mobile phase B: 0.03% NH3▪H2O in acetonitrile (v/v), 100% H2O linear to 50% H2O/50% acetonitrile, hold at 50% H2O/50% acetonitrile for 10 min, with 10 ml/min flow rate. The mixture was then lyophilized to yield 5-((3-(((((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)propyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-(dimethylamino)-3-(dimethyliminio)-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate (s-TCO-TAMRA) (8.7 mg, 78%) as a dark red solid. 1H NMR (400MHz, CD3CN) δ: 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.13 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.49–6.44 (m, 4H), 5.86–5.75 (m, 2H), 5.10 (ddd, J = 16.9, 10.5, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 3.45–3.40 (m, 2H), 3.20–3.15 (m, 2H), 2.96 (s, 12H), 2.31–2.11 (m, 4H), 1.91–1.82 (m, 2H), 1.75–1.69 (m, 2H), 0.92–0.80 (m, 1H), 0.62–0.50 (m, 2H), 0.44–0.36 (m, 2H);13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN) δ: 169.7 (u), 166.6 (u), 158.1 (u), 156.0 (u), 153.7 (u), 153.5 (u), 139.1 (dn), 137.4 (u), 134.8 (dn), 132.0 (dn), 129.6 (dn), 128.8 (u), 125.2 (dn), 124.2 (dn), 109.9 (dn), 107.0 (u), 99.0 (dn), 69.8 (u), 40.4 (dn), 39.3 (u), 38.6 (u), 37.6 (u), 34.4 (u), 33.2 (u), 30.4 (u), 28.3 (u), 25.7 (dn), 22.7 (dn), 21.7 (dn); HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M+H]+ calcd. for C39H45N4O6+ 665.3334, found 665.3330.

5-((3-(((((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)propyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-(dimethylamino)-3-(dimethyliminio)-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate•AgNO3 (s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3).

To a flask containing 5-((3-(((((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)propyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-(dimethylamino)-3-(dimethyliminio)-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate (9.20 mg, 0.0138 mmol, 1.00 equiv) in 1.0 ml methanol was added an acetonitrile (15.2 μL, 1.0 M) solution of silver nitrate (2.59 mg, 0.0152 mmol, 1.10 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford 5-((3-(((((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)propyl)carbamoyl)-2-(6-(dimethylamino)-3-(dimethyliminio)-3H-xanthen-9-yl)benzoate•AgNO3 (13.0 mg, quantitative yield) as red solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN) δ: 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.11–8.07 (m, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 6.74 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.5 Hz, 2H), 6.69 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 6.06(s, 1H), 5.91 (dt, J = 15.8, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5.17–5.10 (m, 1H), 3.87 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.44–3.38 (m, 2H), 3.16–3.12 (m, 14H), 2.40–2.32 (m, 2H), 2.21–2.17(m, 1H), 2.12–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.86–1.80 (m, 1H), 1.77–1.71 (m, 2H), 1.02–0.90 (m, 1H), 0.76–0.61 (m, 2H), 0.50–0.44(m, 2H); HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M+H-AgNO3]+ calcd. for C39H45N4O6+ 665.3334, found 665.3331.

Stability Properties of trans-Cyclooctenes

Stability study of rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-Cyclooct-4-enol (1a major diastereomer) in methanol.

rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-Cyclooct-4-enol (22.0 mg) was mixed with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (9.00 mg). The mixture was dissolved in 1.20 ml CD OD and 1HNMR was taken as time = 0. The sample was stored at 25°C. 1HNMR spectrum was taken after 3 days and 7 days. Overall there was >99% fidelity for rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-cyclooct-4-enol (5OH-TCO major diastereomer) after 3 days and >99% fidelity after 7 days.

Stability study of rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol (1a minor diastereomer) in methanol.

rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol (11.0 mg) was mixed with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (5.00 mg). The mixture was dissolved in 0.60 ml CD3OD and 1HNMR was taken as time = 0. The sample was stored at 25°C. 1HNMR spectrum was taken after 3 days and 7 days. Overall there was >99% fidelity for rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-cyclooct-4-enol (5OH-TCO minor diastereomer) after 3 days and >99% fidelity after 7 days.

Stability test of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (s-TCO) in methanol.

((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (6.10 mg) was mixed with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (4.00 mg). The mixture was dissolved in 0.7 ml CD3OD and 1HNMR was taken as time = 0. The sample was stored at 25°C. 1HNMR spectrum was taken after 3 days and 7 days. Overall there was 96% fidelity for ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (s-TCO) after 3 days and 86% fidelity after 7 days.

Stability test of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol(s-TCO) in phosphate buffered D2O (pD = 7.4).

Phosphate D2O buffer (pD 7.4) was prepared by dissolving sodium dihydrogen phosphate hydrate (NaH2PO4·H2O, 19.3 mg) and disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4, 51 mg) in 5 mL D2O to make a 0.1 M solution, and then adjusting to pD 7.4 by adding DCl. The pD values were measured on an ATI PerpHect LogR pH meter (model 310). pH readings were converted to pD by adding 0.4 units.40

To a mixture of s-TCO (6.14 mg, 0.017 mmol) and phosphate buffered D2O (1 mL, pD = 7.4) was added 4-methoxybenzoic acid (5.59 mg, 0.018 mmol) as an internal standard and monitored by 1 HNMR to observe the stability of s-TCO. Overall there was 69% fidelity for ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (s-TCO) after 3 days at 25°C.

Stability comparisons for non-crystalline trans-cyclooctene derivatives when stored neat at 30 °C.

Neat stability test of rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-Cyclooct-4-enol (1a major diastereomer).

rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-Cyclooct-4-enol (34.51 mg) was dissolved in acetone (3 ml). 1 ml of this acetone solution of rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-cyclooct-4-enol was aliquoted and acetone was dried under reduced pressure, after which 6.06 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added and 1HNMR was taken in CDCl3. The amount of rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-cyclooct-4-enol was determined by 1HNMR as 0.0851 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this acetone solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-cyclooct-4-enol was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 4.79 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in CDCl3. The amount of rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-cyclooct-4-enol was determined as 0.0807 mmol. Overall, there was 95% fidelity for rel-(1R, 4E, pR)-cyclooct-4-enol after 3 days.

Neat stability test of rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol (1a minor diastereomer).

rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol (39.8 mg) was dissolved in acetone (3 ml). 1 ml of this acetone solution of rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol was aliquoted and acetone was dried under reduced pressure, after which 4.49 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added and 1HNMR was taken in CDCl3. The amount of rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol was determined by 1HNMR as 0.0942 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this acetone solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 4.63 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in CDCl3. The amount of rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol was determined as 0.0923 mmol. Overall, there was 98% fidelity for rel-(1R, 4E, pS)-Cyclooct-4-enol after 3 days.

Neat stability test of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol (d-TCO).

((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol (15.0 mg) was dissolved in diethyl ether (3 ml). 1 ml of this ether solution of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9ahexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol was dried under reduced pressure and then mixed with 4.30 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in CDCl3. The amount of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9ahexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol in 1 ml diethyl ether was determined by 1H NMR as 0.0376 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this diethyl ether solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 4.20 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in CDCl3. The amount of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol was determined as 0.00705 mmol. Overall, there was 19% fidelity for ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol after 3 days.

Neat stability test of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (s-TCO).

((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (20.0 mg) was dissolved in diethyl ether (3 ml). 1 ml of this ether solution of ((1R,8S,9r,E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol was dried under reduced pressure and then mixed with 5.30 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in C6D6. The amount of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol in 1 ml diethyl ether was determined by 1HNMR as 0.0409 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this diethyl ether solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 5.10 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in C6D6. The amount of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol was determined as 0.000705 mmol. Overall, there was 2% fidelity ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol (s-TCO) after 3 days.

Neat stability test of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol (oxoTCO).

(E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol (11.6 mg) was dissolved in methanol (3 ml). 1 ml of this methanol solution of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol was aliquoted and methanol was dried under reduced pressure, after which 2.90 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added and 1H NMR was taken in CD3CN. The amount of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol in 1 ml methanol was determined by 1H NMR as 0.0187 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this methanol solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 2.80 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1H NMR was taken in CD3CN. The amount of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol was determined as 0.012 mmol. Overall, there was 37% decomposition for (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol after 3 days.

Neat stability test of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (s-TCO•AgNO3).

((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (57.7 mg) was dissolved in CH3CN (3 ml). 1 ml of this CH3CN solution of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 was mixed with 4.26 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene, concentrated by rotatory evaporation and 1H NMR was taken in CD3CN (as time 0). The amount of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 in 1 ml CH3CN was determined by 1H NMR (CD3CN) as 0.0561 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this CH3CN solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 6.20 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1H NMR was taken in CD3CN. The amount of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 was determined as 0.0543 mmol. Overall, there was 97% fidelity for a neat sample of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 after 3 days.

Neat stability test of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol •AgNO3 (d-TCO•AgNO3).

((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol •AgNO3 (33.8 mg) was dissolved in CH3CN (3 ml). 1 ml of this CH3CN solution of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol •AgNO3 was dried and mixed with 4.40 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene, then 1HNMR was taken in CD3CN. The amount of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9ahexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol •AgNO3 in 1 ml CH3CN was determined by 1HNMR as 0.0283 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this CH3CN solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol •AgNO3 was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 3.60 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in CD3CN. The amount of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 was determined as 0.0267 mmol. Overall, there was 94% fidelity for ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 after 3 days.

Neat stability test of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (oxoTCO•AgNO3).

(E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (28 mg) was dissolved in methanol (3 ml). 1 ml of this methanol solution of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 was aliquoted and methanol was dried under reduced pressure, after which 2.50 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added and 1HNMR was taken in CD3CN. The amount of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 in 1 ml methanol was determined by 1HNMR as 0.0211 mmol. At the meantime, another 1ml of this methanol solution was dried under reduced pressure. This neat sample of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, this sample was mixed with 2.40 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and 1HNMR was taken in CD3CN. The amount of (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 was determined as 0.0204 mmol. Overall, there was 97% fidelity for (E)-(3,4,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-oxocin-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 after 3 days.

Stability studies for trans-cyclooctene silver complexes = in solution.

Stability test of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (s-TCO•AgNO3) in methanol.

((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (4.00 mg) was mixed with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (4.00 mg). The mixture was dissolved in 0.8 ml CD3OD and 1HNMR was taken as time = 0. The sample was then heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days before another 1HNMR spectrum was taken (as time = 3 days). Overall there was 98% fidelity for ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (s-TCO•AgNO3) after 3 days.

Stability test of ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (s-TCO•AgNO3) in DMSO.

((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (4.00 mg) was mixed with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (4.00 mg). The mixture was dissolved in 0.8 ml DMSO-d6 and 1HNMR was taken as time=0 spectrum. The sample was then heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days before another 1HNMR spectrum was taken. Overall there was 96% fidelity for ((1R,8S,9r, E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl)methanol•AgNO3 (s-TCO•AgNO3) after 3 days.

Stability test of ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol •AgNO3(d-TCO•AgNO3) in methanol and DMSO.

To ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol (15.6 mg, 0.847 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added an acetonitrile (0.67 ml, 23.0 mg/ml) solution of silver nitrate (15.8 mg, 0.0931mmol, 1.10 equiv). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The silver complex was dissolved in acetonitrile (3 ml). 1.0 ml of the acetonitrile solution was taken and concentrated under reduced pressure, mixed with 3.90 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and dissolved in 0.8 ml CD3OD. 1HNMR spectrum was taken as time=0. The sample was heated at 30°C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, another 1HNMR spectrum was taken. Overall, there was 95% fidelity for ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 after 3 days.

Another 1.0 ml of the acetonitrile solution was taken and concentrated under reduced pressure, mixed with 5.20 mg 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene and dissolved in 0.8 ml DMSO-d6. 1HNMR spectrum was taken as time=0. The sample was heated at 30 °C in an oil bath over 3 days. After that, another 1HNMR spectrum was taken. Overall, there was 94% fidelity for ((2r,3aR,9aS, E)-3a,4,5,8,9,9a-hexahydrocycloocta[d][1,3]dioxol-2-yl)methanol•AgNO3 after 3 days.

Decomplexation experiment.

In an NMR experiment, Ag-s-TCO-Halo (2e) (5 mg) was dissolved in D2O (0.9 mL), and then added to this solution with aq. NaCl (0.1 mL, 100 mM). The final concentration of the Ag-s-TCO-Halo (2e) was 8.7 mM, and of NaCl was 10 mM. Within 3 minutes, the 1H NMR was remeasured, and no signal was observed. The result is consistent with complete decomplexation of silver, as s-TCO-Halo (1e) is insoluble in D2O. Upon extraction with C6D6, silver free s-TCO-Halo (1e) was recovered and observed by1H NMR.

Preparation of samples for ligand exchange studies by 1H NMR.

To a solution of 1f (3.0 mg, 0.0094 mmol) in 0.8 mL MeOH was added 0.37 mL of a 37.8 mM methanolic stock solution of AgNO3 (2.4 mg, 0.014 mmol). The mixture was allowed to stir for 15 min, and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The mixture was then dissolved in CD3OD and 1H NMR spectrum of a solution where the ratio of 1f: silver nitrate was 1.00:1.50. Similar procudures were used to produce 1H NMR spectra where the ratios of 1f: silver nitrate was 1.00:1.00, 1.00: 0.50 and 1.00: 0.25

HeLa cells preparation.

HeLa cells were cultured in complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI FBS), 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-alanyl-L-glutamine dipeptide (glutaMAX), and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin to near confluency in five T175 flasks. Media was aspirated cells washed three times with 5 mL DPBS and treated with 5 mL 0.25% trypsin-EDTA at 37 °C and 5% CO2, until cells are dislodged from flask bottom. Trypsin was quenched with 5 mL of complete DMEM and triturated to remove clumps. Cells were centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 3 minutes, supernatant removed, and the cell pellet resuspended in 10 mL complete DMEM. Cells were counted with a Countess device, adjusted to 6×105 cells/mL with complete DMEM, and 2 mL added per well of 6-well plates (for in-gel experiment) or 6 cm MatTek dishes for imaging experiments. Cells were allowed to adhere overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

HeLa cells transfection.

Media was aspirated and cells were washed three times with 1 mL DPBS and 1 mL antibiotic-free complete DMEM was added to each well or MatTek dish. Opti-MEM/lipofectamine 2000 solution was prepared by mixing together 62.5 μL Opti-MEM and 1.5 μL lipofectamine 2000 per well to be transfected and the mixture incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. Opti-MEM and Halo-H2B-GFP plasmid DNA were prepared by mixing 62.5 μL Opti-MEM and 0.5 μg DNA per well to be transfected and the mixture was incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. The lipofectamine 2000 and DNA mixtures were then combined and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. 125 μL of the lipofectamine 2000/DNA mixture was added to each well and after briefly rotating the plates to ensure proper mixing in the wells, the cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 3 hours. Media was then aspirated from each well and replaced with 2 mL complete DMEM and the cells incubated overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

HaloTag conjugation.

Media was aspirated from transfected cells, which were then washed three times with 1 mL DPBS and 1 mL complete DMEM containing 2 μM MeTz-Halo was added to each well. For a negative control, 1 mL complete DMEM containing DMSO control was added to three wells. For a positive control, 1 mL complete DMEM containing 1 μM TAMRA-Halo was added to three wells. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 30 minutes, media aspirated, and cells washed three times with 1 mL DPBS.

In-gel fluorescence analysis of time course tetrazine ligation.

DPBS was aspirated from each well and replaced with 1 mL complete DMEM containing 2 uM s-TCO-TAMRA•AgNO3 and cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for time periods varying from 10 seconds to 2 hours. At the end of indicated time, reactions were quenched by addition of TCO-NH2 (1 mL, 100 uM). Media was aspirated from wells, TCO-NH2 (1 mL, 100 uM) added to each well, and cells were scraped and transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000xg for 3 minutes and supernatant aspirated.

Protein gel electrophoresis, in-gel fluorescence, and western blotting.

Cell pellets were lysed in 50 μL 1% SDS in DPBS with several pulses of a probe sonicator and quantitated with a Pierce BCA assay. 30 μg aliquots of each sample were adjusted to a total volume of 39 μL with 1% SDS and 15 μL 4× LDS and 6 μL NuPAGE 10× sample reducing agent were added. Samples were then heated at 72 °C for 10 minutes. 18 μL of each sample was then loaded per lane of 12 well NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gel ran in NuPAGE MES running buffer at 140 V for 60 minutes. Gels were then removed from cassettes, transferred to distilled water, and immediately scanned on Typhoon FLA9500 variable mode imager with a long-pass LPG filter. Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using iBlot2 gel transfer system and membranes incubated in 10 mL Pierce Protein-Free (PBS) blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Blocking buffer was removed and additional 5 mL blocking buffer containing 1:1,000 rabbit anti-HaloTag polyclonal antibody was added and blot incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The membrane was washed with 15 mL TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 10 minutes on rotating platform three times. 10 mL TBST containing 1:10,000 goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW secondary antibody was added and allowed to incubate for 1 hour at room temperature. The membrane was washed with 15 mL TBST for 10 minutes on rotating platform five times. The membrane was scanned on Licor Odyssey CLx system. ImageQuant TL 1D v8.1 software was used to determine intensity of in-gel fluorescence bands and normalized to total HaloTag protein as a % of positive control.

Confocal microscopy.

DPBS was aspirated from well and replaced with 1 mL of complete DMEM containing 500 nM s-TCO-TAMRA and cells incubated for 60 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2. TCO-NH2 (1 mL, 100 uM) was then added to each well, and cells washed twice with TCO-NH2 (1 mL, 100 uM). Cells were incubated in 1 mL of fresh phenol red-free complete DMEM for an hour, and media changed after 30 minutes with fresh phenol red-free complete DMEM before imaging on Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted microscope with a Yokogawa CSU-X1M 5000 dual camera spinning disk system and acquired with a Photometrics Evolve 512 Delta camera using Zen Blue 2012 software. Cells were visualized using a 40×/1.3 numerical aperture (NA) objective and illuminated with the 488 and 561 laser lines. Green and red emission was collected sequentially (BP 525/50 and BP 617/73 respectively).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01EB014354, R01DC014461, and NSF DMR-1506613 and a grant from Pfizer. Spectra were obtained with instrumentation supported by NIH grants P20GM104316, P30GM110758, S10RR026962, S10OD016267 and NSF grants CHE-0840401, CHE-1229234, and CHE-1048367. We thank Dr. Shuyu Xu and He Zhang for IR(ATR) characterization and Prof. Dr John Koh for insightful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).Blackman ML; Royzen M; Fox JM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Devaraj NK; Weissleder R; Hilderbrand SA Bioconjug. Chem 2008, 19, 2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Row RD; Prescher JA Acc. Chem. Res 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wu H; Devaraj NK Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kang K; Park J; Kim E Proteome Sci. 2016, 15, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cycloadditions in Bioorthogonal Chemistry; Vrabel M; Carell T, Eds.; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Wu H; Devaraj NK Top. Curr. Chem 2016, 374, 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rossin R; Robillard MS Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2014, 21, 161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lang K; Chin JW ACS Chem. Biol 2014, 9, 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Knall AC; Slugovc C Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 5131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Selvaraj R; Fox JM Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2013, 17, 753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Oliveira BL; Guo Z; Bernardes GJL Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 4895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Patterson DM; Nazarova LA; Xie B; Kamber DN; Prescher JA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 18638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kamber DN; Nazarova LA; Liang Y; Lopez SA; Patterson DM; Shih H-W; Houk KN; Prescher JA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 13680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yang J; Šečkutė J; Cole CM; Devaraj NK Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 7476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Eising S; Lelivelt F; Bonger KM Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2016, 55, 12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Eising S; van der Linden NGA; Kleinpenning F; Bonger KM Bioconjug. Chem 2018, 29, 982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lang K; Davis L; Wallace S; Mahesh M; Cox DJ; Blackman ML; Fox JM; Chin JW J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 10317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Niederwieser A; Späte A-K; Nguyen LD; Jüngst C; Reutter W; Wittmann V Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lee Y-J; Kurra Y; Yang Y; Torres-Kolbus J; Deiters A; Liu WR Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Oliveira BL; Guo Z; Boutureira O; Guerreiro A; Jiménez-Osés G; Bernardes GJL Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 14683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Liu K; Enns B; Evans B; Wang N; Shang X; Sittiwong W; Dussault PH; Guo J Chem. Commun 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Darko A; Wallace S; Dmitrenko O; Machovina MM; Mehl RA; Chin JW; Fox JM Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Taylor MT; Blackman ML; Dmitrenko O; Fox JM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 9646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kozma E; Nikić I; Varga BR; Aramburu IV; Kang JH; Fackler OT; Lemke EA; Kele P ChemBioChem 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Lambert WD; Scinto SL; Dmitrenko O; Boyd SJ; Magboo R; Mehl RA; Chin JW; Fox JM; Wallace S Org. Biomol. Chem 2017, 15, 6640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Winterbourn CC; Metodiewa D Free Radic. Biol. Med 1999, 27, 322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Squillacote ME; DeFellipis J; Shu QJ Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 15983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Fox J; Fang Y; Zhang H; Huang Z; Scinto S; Yang J; am Ende CW; Dmitrenko O; Johnson DS Chem. Sci 2018, 7, 1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Rossin R; Van Den Bosch SM; Ten Hoeve W; Carvelli M; Versteegen RM; Lub J; Robillard MS Bioconjug. Chem 2013, 24, 1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Crisponi G; Nurchi VM; Fanni D; Gerosa C; Nemolato S; Faa G Coord. Chem. Rev 2010, 876–889. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Giulivi C; Cadenas E Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1993, 303, 152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Cope AC; Bach RD Org. Synth. Coll Vol. 5 1973, 315. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Deneke SM Curr. Top. Cell. Regul 2001, 36, 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Murrey HE; Judkins JC; am Ende CW; Ballard TE; Fang Y; Riccardi K; Di L; Guilmette ER; Schwartz JW; Fox JM; Johnson DS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).(a) For additional studies on trans-cycloheptenes:Santucci J; Sanzone JR; Woerpel KA Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 2016, 2933. [Google Scholar]; (b) Greene MA; Prévost M; Tolopilo J; Woerpel KA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 12482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Santucci J; Sanzone JR; Woerpel KA Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 2016, 2933. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sanzone JR; Woerpel KA Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Rencken I; Boeyens JCA; Orchard SW J. Cryst. Spec. Res 1988, 18, 293. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Blizzard RJ; Backus DR; Brown W; Bazewicz CG; Li Y; Mehl RA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Egloff C; Jacques SA; Nothisen M; Weltin D; Calligaro C; Mosser M; Remy J-S; Wagner A Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Glasoe PK; Long FA J. Phys. Chem 1960, 188. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Medvetz DA; Hindi KM; Panzner MJ; Ditto AJ; Yun YH; Youngs WJ Met. Based. Drugs 2008. doi: 10.1155/2008/384010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.