Abstract

The emphasis in addictions research has shifted toward a greater interest in identifying the mechanisms involved in patient behavior change. This systematic review investigated nearly 30 years of mediation research on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for alcohol or other drug use disorders (AUD/SUD).

Method.

Study inclusion criteria targeted analyses occurring in the context of a randomized clinical trial where both intervention/intervention ingredient to mediator (a path) and mediator to outcome (b path) paths were reported. Between- and within-condition analyses were eligible, as were studies that formally tested mediation and those that conducted path analysis only.

Results.

The review sample included K = 15 reports of primarily between-condition analyses. Almost half of these reports utilized Project MATCH (k = 2) or COMBINE (k = 4) samples. Among the mediator candidates, support for changes in coping skills was strongest, although the specificity of this process to CBT or CBT-based treatment remains unclear. Similarly, support for self-efficacy as a statistical mediator was found in within-, but not between-condition analyses.

Conclusions.

A coherent body of literature on CBT mechanisms is significantly lacking. Adopting methodological guidelines from the Science of Behavior Change Framework, we provide recommendations for future research in this area of study.

Keywords: Addiction, Coping Skills, Mechanisms of Behavior Change, Relapse Prevention, Science of Behavior Change, Statistical Mediation

Introduction

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most commonly used behavior therapies for alcohol or other drug use disorders (AUD/SUD; National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services [N-SSATS], 2017). CBT has been considered evidence-based for AUD since Chambless and Hollon’s 1998 task-force report on Empirically-Supported Treatment for adult mental health disorders (see also, Miller et al., 1995). Additionally, there have been several qualitative and quantitative reviews demonstrating CBT efficacy across drug types, when compared to no or minimal intervention (Carroll, 1996; Carroll & Onken, 2005; Irvin, Bowers, Dunn, & Wang., 1999; Magill & Ray, 2009; Magill, Ray, Kiluk, Hoadley, Bernstein, Tonigan, & Carroll, 2019). Similar to other addiction therapies, research does not show superior efficacy for CBT in contrast to another evidence-based modality (Magill & Ray, 2009; Magill et al., 2019). As behavior therapies for addiction continue to evolve, become more integrated, and are delivered in increasingly varied formats, questions about essential ingredients and/or mechanisms become more significant (Carroll & Kiluk, 2017). The evidence for causal processes in CBT for AUD/SUD, unfortunately, has not attained the same level of clarity as the evidence for its efficacy.

In the past 20 years, the emphasis in addictions research has shifted toward a greater interest in identifying the mechanisms involved in behavior change. This is a science-based approach for optimizing behavioral treatments that may result in greater treatment efficacy and efficiency (Huebner & Tonigan, 2007; Mechanisms of Behavior Change Satellite Committee, 2018). Moreover, this direction has been formalized by the United States’ National Institutes of Health (NIH) as a trans-diagnostic research initiative to inform a mechanistic, experimental medicine-based approach to behavioral health (i.e., Science of Behavior Change; NIH Common Fund Initiative). The central rationale is described as follows:

“In general, behavior change interventions have not been based on explicit tests of specific target engagement using well-validated assays. Instead, behavior change interventions tend to combine multiple components meant to engage a variety of targets, whether specified or not. Moreover, few intervention studies are designed to test whether the intervention actually engages the (multiple) target(s) it is meant to engage, and whether engagement of the target(s) produces the desired behavior change. As a result, even successful intervention studies do not generally inform behavior change research beyond the (often very specific) context in which they are tested.” (Nielsen et al. 2018; p. 5)

A mechanistic understanding of CBT for AUD/SUD is particularly important given it is a complex package of multiple intervention components, where very little is known about individual component efficacy. Utilization of components may also vary by study, but for the purposes of this review, we provide a broad overview of CBT components as follows: 1) identifying intrapersonal and interpersonal triggers for substance use, 2) skills training to develop behavioral alternatives to substance use, 3) strategies for addressing craving, drug-refusal, affect regulation, and social skills, and 4) increasing nonuse-related activities and other positive reinforcers that may promote behavior change maintenance. Regarding mechanisms of change, increases in self-efficacy and behavioral coping have been the most commonly proposed and tested (Mastroleo & Monti, 2013). More recently, however, cognitive and neural correlates have also been considered (e.g. Chung et al., 2016; DeVito, Dong, Kober, Xu, Carroll, K. M., & Potenza, 2017; Jurado-Barba et al., 2015).

We begin our discussion of the search for CBT mechanisms with a seminal article by Morgenstern and Longabaugh (2000) that examined 10 secondary analyses of randomized clinical trials for evidence of statistical mediators of CBT efficacy. The authors used systematic review to examine a sample of studies meeting strict inclusion criteria. Specifically, an adapted causal steps approach (Baron & Kenny, 1986) specified how “presumptive support” for mediation would be met. The adapted criteria emphasized steps one (i.e., the CBT condition correlates with the outcome), two (i.e., the CBT condition correlates with the mediator), and three (i.e., the mediator correlates with the outcome, covarying CBT condition), and argued that steps one and three (i.e., the CBT effect is reduced when the mediator is covaried) would depend on whether the control condition was a “clearly weaker” treatment. In other words, the authors recognized that these steps would likely be untenable when CBT was contrasted with another evidence-based modality. The authors found no studies meeting their presumptive support criterion out of the 18 putative cognitive (i.e., measures of self-efficacy) or behavioral (i.e., self-reported or role-played measures of coping skills) mediators examined. Failure of support was most often found at the CBT condition to mediator path (i.e., step two or a path), but close to half of the paths from mediator to outcome (i.e., step three or b path) were not tested (i.e., seven of 18). Therefore, it is unknown whether these analyses were not conducted or not reported, and as such, evidence for the mediator to outcome path may be similarly inconclusive. The authors concluded there was little to no evidence to further our understanding of how CBT works, and by translation, its essential mechanisms of change.

More recently, Carroll and Kiluk (2017) conducted a comprehensive review of the state of knowledge on CBT for AUD/SUD, including evidence for mechanisms of change. The authors pointed out that there was very little focused mediation research, and discussed two studies where mediation was demonstrated. In the first example, COMBINE (Anton et al., 2006) participants in a CBT plus motivational interviewing condition (i.e., combined behavioral intervention [CBI]) who received a CBT-based drink refusal module had superior drinking outcomes compared to those who did not; this effect was mediated by increases in self-reported self-efficacy (Witkeiwitz, Donovan, & Hartzler, 2012). In the second example, the effects of a technology-based CBT program (i.e., CBT4CBT) added to usual care, in relation to drug use outcomes was mediated by changes in the quality of participants’ coping behaviors (Kiluk, Nich, Babuscio, & Carroll., 2010). In reviews by Longabaugh, Magill, Morgenstern, & Huebner (2013) and Kiluk (2015; cf. Magill, Kiluk, McCrady, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 2015), at least one of the two noted examples were also highlighted, which underscores there have been few available cases where mediation of CBT for AUD/SUD was tested and supported. This state of the literature is ubiquitous; that is, identification and validation of mechanisms by type of intervention or disease/risk behavior is lacking in most behavioral modalities (Nielson et al., 2018).

Study purpose

This review seeks to identify and synthesize the existing literature on mediators of CBT for AUD/SUD. Because we sought to minimize bias due to reporting status, we considered only studies that formally tested mediation or that tested both the a and b paths of a hypothesized causal chain, whereby CBT effect on substance use outcomes was transmitted via one or more intervening variables. While a larger review of the full spectrum of secondary analyses of CBT efficacy trials (i.e., all a or b path studies) would certainly be of interest, it is beyond the scope of this review that targets mediation research in particular. The current review considers between-condition mediation tests (i.e., CBT in contrast to some form of experimental control as the a path predictor) as the optimal mode of analysis because randomization at the a path of the causal process model can be assured (MacKinnon, 2008). However, within-condition analyses were also of interest. Here, within-condition mediation analyses typically examine a specified intervention ingredient (e.g., a component or strategy) in relation to a subsequent mediator of study outcome. While specificity (i.e., uniqueness to CBT) of the intervention process model cannot be inferred in this case, these models do inform our understanding of how CBT works as well as provide a basis for future hypothesis generation. Finally, as a means of moving this field forward, we advocate for adoption of terminological and methodological guidelines from the Science of Behavior Change Framework (SOBC; see e.g., Nielson et al., 2018) in our discussion.

Method

Study inclusion criteria

CBT for AUD/SUD is defined as a time-limited, multi-session intervention that targets cognitive, affective, and environmental triggers for substance use and provides training in coping skills to help an individual achieve and maintain abstinence or harm reduction. To be eligible for review, studies had to have examined CBT or CBT-based (e.g., integrative CBT, combined with another psychosocial therapy or pharmacotherapy) treatment efficacy in the context of a randomized clinical trial with adult alcohol or other drug using participants. Studies also had to present secondary analyses of how the experimental condition engaged one or more patient-level targets (e.g., self-efficacy, coping skills, craving) to achieve intervention effects on use-related outcomes. Here, studies testing mediation or reporting both a and b path analyses were eligible. Moreover, between (i.e., randomized assignment to CBT versus another condition was the a path predictor) or within (i.e., a specified CBT ingredient within the randomized CBT condition was the a path predictor) condition analyses were of interest, although these studies are reported separately. Finally, studies had to be English language, published in peer-reviewed journals between 1990 and 2019.

Literature search

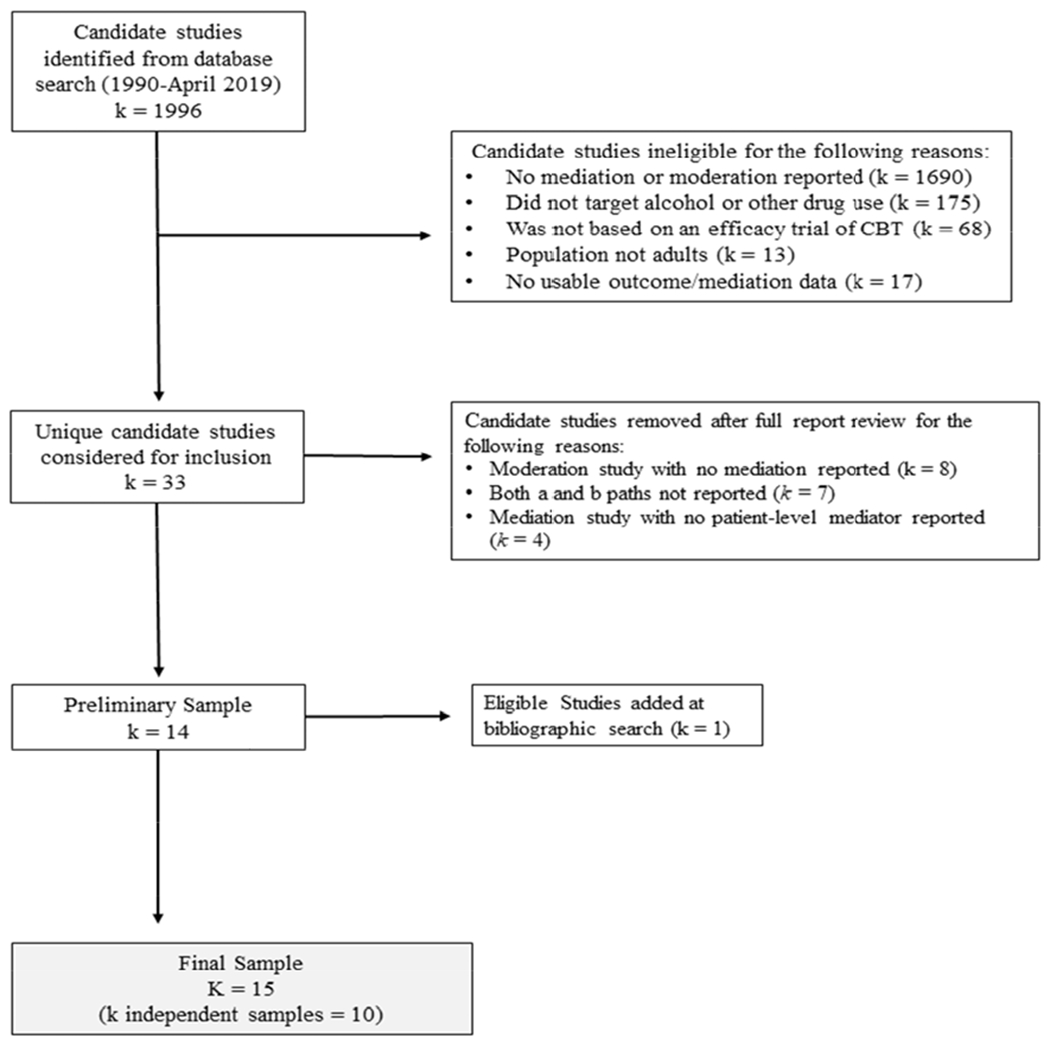

The literature search was conducted as one aspect of a meta-analytic project on CBT treatment for AUD/SUD (R21#AA026006). For the present report, a separate title, abstract, and keyword search string was constructed: (cognitive-behavioral therapy OR cognitive-behavioural therapy OR CBT OR relapse prevention OR coping skills training OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR behavioral therapy) AND (alcohol OR cocaine OR methamphetamine OR stimulant OR opiate OR heroin OR marijuana OR cannabis OR illicit drug OR substances OR dual disorder OR polysubstance OR dual diagnosis) AND (mediation OR secondary analysis OR path analysis OR meta-analysis) AND (1990/01/01[Date - Publication]: 2019/04/21 [Date - Publication]), and entered into PubMed. Abstract review was conducted by a trained rater and final inclusion and exclusion was confirmed by the first author. Finally, a bibliographic search of eligible studies and literature reviews was completed (Carroll & Kiluk, 2017; Carroll & Onken, 2005; Lonagabaugh et al., 2013; Magill et al., 2015; Mastroleo & Monti, 2013; Morgenstern & Longabaugh, 2000). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of study inclusion, meeting QUORUM guidelines (Moher, Cook, Eastwood, Olkin, Rennie, & Stroup, 1999). The final sample of studies was K = 15 reports on k = 10 independent samples.

Figure One: Flow of study inclusion/exclusion.

Bibliographic search included the following reviews: Carroll & Kiluk (2017); Carroll & Onken (2005); Lonagabaugh et al. (2013); Magill et al. (2015); Mastroleo & Monti (2013); Morgenstern & Longabaugh (2000).

Study variables of interest

A range of variables were extracted from primary studies to provide aggregate data on sample characteristics. Sample-level descriptors were: mean age of participants, percent female participants, percent white participants, primary drug target (i.e., alcohol, polydrug, other), substance use severity (i.e., dependence sample, at risk or heavy use sample), CBT condition type (i.e., CBT, CBT-based [i.e., combined with another psychosocial therapy or pharmacotherapy, technology-based CBT), contrast condition type (i.e., minimal [e.g., waitlist], non-specific therapy [e.g., treatment as usual], specific therapy [e.g., Motivational Interviewing, Twelve-Step Facilitation]), treatment length (i.e., number of planned sessions), mediator variables tested (i.e., self-efficacy, coping skills, craving/affect regulation/stress, other), study context (i.e., community sample, specialty substance use or mental health clinic, other setting), publication country (i.e., United States, other country), and mediation study quality score (see below). Study-level descriptors (see Table 1) were: sample N, CBT condition, contrast condition, and a and b paths tested/results. Data extraction guidelines were detailed in a study codebook available, upon request, from the first author. Data were extracted using consensus methods between the first and fourth authors (independent agreement rate, prior to consensus meetings, was 94%).

Table One:

Study-Level Characteristics, including ab path model

| Author Name (date) | N | CBT condition | Contrast condition | a path1 | b path2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between-condition studies | |||||

| Brown et al. (2002) | 131 | Structured Relapse Prevention | Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) | CBT + confidence - temptation ns 12-step adoption |

confidence - ASI, days used temptation + ASI, days used |

| Glasner-Edwards et al. (2007) | 148 | Integrated, Dual Disorder-Specific Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (ICBT) | Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF) | ICBT ns self-efficacy ns affect regulation ns social support - 12 step affiliation |

self-efficacy + days abstinent 12 step affiliation + days abstinent |

| Johnson et al. (2006) | 1863 | Cognitive Behavioral Veteran’s Administration Program (CB program) | 12 Step Veteran’s Administration Program (12 step program) | CB program + self-efficacy ns CB-specific coping skills ns general coping skills - 12 step coping skill |

mediators ns abstinence, ns reduced problems |

| Kiluk et al. (2010) | 52 | Technology delivered CBT (CBT4CBT) plus treatment as usual (TAU) | treatment as usual (TAU) | CBT4CBT ns quantity of coping response + quality of best coping response + quality of overall coping response |

quality of best coping response + days abstinent quality of overall coping response + days abstinent |

| Kiluk et al. (2017) | 71 | Technology delivered CBT (CBT4CBT) plus treatment as usual (TAU) | treatment as usual (TAU) | CBT4CBT ns quality of best coping response ns quality of overall coping response |

quality of overall coping response + days abstinent |

| Litt et al. (2003) | 128 | Coping Skills Therapy (CBT) | Interactional Group Therapy (IGT) | CBT ns total coping score | total coping score + abstinent days, - heavy drinking days, + total abstinence, + time to lapse |

| Litt et al. (2018) | 166 | Packaged Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (PCBT) | case management (CM) | CBT ns social network measures ns self-efficacy ns coping skills ns emotional distress |

coping skills + treatment responder status |

| **Maisto et al. (2015) | 952 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET)/Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF) | CBT X alliance + self-efficacy | self-efficacy - drinking days, - drinks per drinking day, - drinking consequences |

| **Roos et al. (2017) | 323 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) | CBT + coping skills | coping skills - drinking days ns heavy drinking days |

| **Roos et al. (2017) | 338 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF) | CBT + coping skills | coping skills - drinking days - heavy drinking days |

| Sandahl et al. (2004) | 49 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Psychodynamic Group (PG) | CBT - perceived control ns self-efficacy |

perceived control ns abstinent days self-efficacy + abstinent days |

| *Subbaraman et al. (2013) | 431 | Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) | Placebo with no CBI | CBI - craving | craving + abstinent days |

| *Subbaraman et al. (2013) | 418 | Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) with naltrexone | Placebo with no CBI | CBI - craving | craving + abstinent days |

| Sugarman et al. (2010) | 48 | Technology delivered CBT (CBT4CBT) plus treatment as usual (TAU) | treatment as usual (TAU) | CBT4CBT ns total coping score | total coping score - frequency of drug use |

| *Witkiewitz et al. (2018) | 1124 | Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) plus medication management (MM) | All MM only conditions | CBI + broad coping repertoire | broad coping repertoire - heavy drinking days, - drinking consequences |

| Within-condition studies | |||||

| *Hartzler et al. (2011) | 157 | Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) | bond + self-efficacy | self-efficacy - drinking frequency, - drinking consequences, - global symptom severity |

|

| *Hartzler et al. (2011) | 607 | Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) plus medication management (MM) | bond ns self-efficacy | self-efficacy - drinking frequency, - drinking consequences, - global symptom severity |

|

| *Witkiewitz et al. (2012) | 776 | Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) | drink refusal module + self-efficacy | self-efficacy - drinking frequency | |

Notes. K = 15, with 10 independent samples. It a study considered multiple between- or within-condition models, each contrast contributed a row. Studies contributing multiple rows are: Hartzler et al. (2011); Roos et al. (2017); Subbarraman et al. (2013). CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; ASI = Addiction Severity Index; ns = non-significant; + = increase; - = decrease. * COMBINE Study (Anton et al., 2006). ** Project MATCH Research Group (1997). Study-level notes. Brown et al. (2002) 1 Condition differences at post-treatment only. 2 Remaining use outcomes ns (three measures). Glasner-Edwards et al. (2007) 2 Affect regulation and social support ns. Johnson et al. (2006) 1 Self-efficacy effect only for CB program participants who did not attend continuing care. 2 Of 21 CB, 12 step, and general coping measures, all program by variable effects on outcome were ns for CB programs. Mediation not tested for CB programs. Kiluk et al. (2010) 2 Urine screen outcomes ns. Mediation demonstrated for CBT4CBT efficacy on 8 week days abstinence via quality of coping response. Kiluk et al. (2017) 1 When participants with low coping at baseline were examined, a time by condition effect for CBT4CBT on quality of coping response was observed. 2 no mediation effects were detected. Litt et al. (2003) 1Given coping did not differ by condition, the authors examined self-efficacy and motivation as patient factors associated with changes in coping and subsequent abstinent days; the model was supported. Litt et al. (2018) 1 A total of 10 measures were examined. 2The study found a significant mediation effect for coping skills in the responder v non-responder analyses, but not the late relapse v non-responder analyses. Maisto et al. (2015) 2 Mediation effect for CBT by alliance interaction, as a predictor of self-efficacy and subsequent drinking outcome ns (3 measures). Roos et al. (2017) 1 CBT effect on coping skills present for outpatient participants with high dependence severity. 2 Moderated mediation effects supported. Sandahl et al. (2004) 1 A total of 7 self-efficacy and self-control sub-scales tested. 2 Testing control and social pressure sub-scales. Subbaraman et al. (2013) 2 Mediation effect significant for cravings measured at week 12, but not week 4 for CBI. Mediation effect significant at weeks 4 and 12 for CBI with naltrexone. Sugarman et al. (2010) 1 Sample overlapping with Kiluk et al. (2010). 2 Correlation of total coping change and drug use frequency more negative in CBT4CBT condition. Witkiewitz et al. (2018) 1 CBI predicted reduced odds of being in the narrow compared to broad coping repertoire class. 2 Mediation demonstrated for membership in the high versus low and occasional versus low heavy drinking and consequence classes. Hartzler et al. (2011) 1 The study examined therapeutic bond sub-scale. 2 Mediation demonstrated within the CBI only condition. Witkiewitz et al. (2012) 2 Mediation demonstrated for end of treatment and 12-month outcomes.

Measurement of mediation study quality

Examining mechanisms of intervention effects can be considered an iterative endeavor beginning with theoretical formulation, followed by path analysis, mediation analysis, and satisfying incremental causal criteria (e.g., Kazdin & Nock, 2003). As such, the present review incorporated an assessment of mediation study quality to inform knowledge on progress as well as methodological standards in this body of literature. A review of available quality rating forms yielded a small selection, with key sources in the area of pain etiology and treatment. An experimental mediation rating form (Mansell, Kamper, & Kent, 2013) adapted for systematic review of observational mediation research (Lee, Hubscher, Moseley, Kamper, Traeger, Mansell, & McAuley, 2015) was the basis for the current measure that additionally extends to the inclusion of regression path models.

The current measure was tailored for optimal relevance to the study of mechanisms of intervention effects. In this regard, three items were added. First, an item assessed study status as a mediation or path model, with the former considered the more stringent test of the candidate mechanism. Second, we considered design elements that would further conclusions of causality and specificity for the candidate mechanism in relation to the intervention of interest (i.e., a between-rather than within-condition a path predictor). Finally, in between-condition studies, the control condition was assessed for status as a “clearly weaker” treatment (Morgenstern & Longabaugh, 2000). In other words an ideal, between-condition a path model would include a control condition that should have no effect on the mediator target. The result was a 10 item measure with response options of “yes”, “no” and “not applicable”. See Table 2 and Supplement A for details. Following standard methods for bias assessment in clinical trials (e.g., Higgins & Green, 2011), there is no total score, average score, or quality benchmarks for the measure. Summary data at the study-or sample-level is provided in the form of percent yes-status items. The current quality rating form can be used to summarize the nature of a body of mediation or path model studies that are specifically focused on understanding mechanisms of intervention effects.

Table Two:

Study Quality Rating for path/mediation analyses of intervention process in the context of clinical trials

| Study author (date) | Theoretical framework | Mediation test | Established analytic method | Power analysis | Psychometrics reported and acceptable | Temporal a path | Temporal b path | Between- condition a path | Clearly weaker control | Covariate adjusted b path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al. (2002) | yes | no | no | no | no | yes | no | yes | no | no |

| Glasner-Edwards et al. (2007) | yes | no | no | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Hartzler et al. (2011) | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | no | na | yes |

| Johnson et al. (2006) | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Kiluk et al. (2010) | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Kiluk et al. (2017) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Litt et al. (2003) | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Litt et al. (2018) | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Maisto et al. (2015) | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Roos et al. (2017) | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Sandahl et al. (2004) | yes | no | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Subbaraman et al. (2013) | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Sugarman et al. (2010) | yes | no | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Witkiewitz et al. (2012) | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | no | na | yes |

| Witkiewitz et al. (2018) | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Notes. K = 15. na = not applicable. For details on items see Supplement A.

Results

Systematic review of study findings

The body of literature on mechanisms of CBT for AUD/SUD was heterogeneous to the extent that a systematic review, rather than meta-analysis, was undertaken. Specifically, among the sample of 15 reports, study design, mediators, methods of measurement and statistical analyses were highly variable and would therefore not provide a meaningful average. Instead, we first summarize the literature at the sample-level. Next, study-level characteristics and path/mediation model results are reported in Table 1. Results are organized by between- and within-condition studies, as well as by type of mediator target. Finally, study quality is summarized in Table 2 and narratively, to inform future research in this area.

Sample-level descriptors

Of the 15 eligible reports, k = 4 were secondary analyses of the COMBINE study (Anton et al., 2006) and k = 2 were secondary analyses of Project MATCH (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997). As such, there were k = 10 independent samples (Kiluk et al., 2010 and Sugarman, Nich, & Carroll, 2010 provided two reports on one sample) and a total N of 4177 individuals were treated (range = 48 to 1863). These samples had a mean age of 43.6 years old (SD = 3.3), were 31.2% female (SD = 18.2) and 73.3% white (SD = 20.2). Half of studies targeted alcohol use (50%) followed by polydrug use (40%). These were primarily participants with an AUD or SUD (80%) treated in a specialty addictions and/or mental health treatment setting (90%). The average number of planned sessions was 15 with a range of 5 to 36. The efficacy trials were most often conducted in the United States (80%). Finally, among the full sample of models examined, close to half tested some form of integrative CBT and contrasted the experimental condition with another active treatment. The mediators tested in these models were primarily self-efficacy, coping skills, craving/affect regulation/stress, or other (e.g., social mechanisms, 12 step-based mechanisms).

Between-condition studies

Self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy is defined as a belief in one’s ability enact a behavior or series of behaviors that will achieve a specific outcome. In the addictions, self-efficacy has been measured as a self-report indicator, with positive (e.g., confidence) or negative (e.g., temptation) valence, and includes related constructs such as perceived self-control or locus of control. Of the six studies examining self-efficacy as a between-condition mediator of CBT-based intervention effects, two path models were supported (Brown, Seranigan, Tremblay, & Annis, 2002; Maisto et al., 2015). Of these, Maisto and colleagues (2015) tested, but did not demonstrate statistical mediation. Further, in this study of Project MATCH participants, the a path model from CBT to self-efficacy, in contrast to twelve-step facilitation (TSF) and motivational enhancement therapy (MET), held only at high levels of total working alliance (Horvath & Greenberg, 1986). Brown and colleagues (2002) tested and supported a path model for CBT compared to TSF among aftercare participants. The model showed differential increases in confidence and decreases in temptation were related to subsequent reduced addiction severity, but not use frequency and time to lapse measures. Of the remaining four studies, three showed failure at the a path of the mediation model. Specifically, CBT or CBT-based interventions did not produce differential gains in self-efficacy in contrast to TSF among depressed participants with an SUD (Glasner-Edwards, Tate, McQuaid, Cummins, Granholm, & Brown, 2007), and in contrast to case management (Litt, Kadden, & Tennen, 2018) and psychodynamic group therapy (Sandahl, Gerge, & Herlitz, 2004) among AUD participants. With respect to the b path, self-efficacy related to the majority of substance use outcomes reported. In the one study where self-efficacy did not predict follow-up outcome, CBT-based Veteran’s Administration (VA) programs showed higher posttreatment self-reported self-efficacy than those based on a 12 step approach (Johnson, Finney, & Moos, 2006). In summary, the six studies reviewed provided little to no conclusive support for increased self-efficacy as one unique mediator through which CBT and CBT-based interventions are effective with AUD/SUD.

Coping skills.

Coping skills incorporate a broad class of self-regulatory cognitions or behaviors that are thought to result in reduction of negative outcomes, such as substance use or other risk behaviors. In the studies reviewed, coping skills were most often measured by self-report of the quantity of skills enacted, including general coping measures and those that were considered CBT-specific (i.e., coping behaviors thought to be targeted by the intervention). A smaller portion of studies examined coping via quality measures, and utilized third party observation of behavioral coping tasks. A total of eight studies examined coping skills as a mechanism of CBT or CBT-based intervention efficacy. Among these studies, five showed path model support and, of the five, four additionally supported statistical mediation. First, Kiluk and colleagues (2010; 2017) examined coping among AUD/SUD participants who received a technology-delivered CBT addition to usual care (CBT4CBT). In the 2010 study of SUD participants, observer-rated quality of coping, but not quantity, mediated early follow-up abstinence. The subsequent study (Kiluk et al., 2017) supported a moderated path model (i.e., the path model held for those with low coping skills at baseline), but not mediation. Next, Roos, Maisto, and Witkiewitz (2017) showed that among Project MATCH outpatients with high dependence severity, CBT differentially predicted follow-up coping skills in contrast to both TSF and MET, and a moderated mediation model was demonstrated. In a latent class mediation model tested with COMBINE Study participants, membership in a class characterized by broad coping capacity (i.e., a higher range of skills utilized) was associated with receipt of the combined behavioral intervention (CBI) as well as membership in the low versus high or occasional follow-up heavy drinking classes. The study supported mediation across these associations (Witkiewitz, Roos, Tofighi, & Van Horn, 2018). Finally, changes in coping skills mediated follow-up, treatment-responder status among AUD participants assigned to CBT in contrast to case management (Litt et al., 2018). In the three remaining studies, CBT or CBT-based interventions failed to show a differential a path relationship to coping skills in contrast to 12 step VA programs (Johnson et al., 2006), interactional group therapy (Litt, Kadden, Cooney, & Kabela, 2003), and treatment as usual (Sugarman, Nich, & Carroll, 2010). Therefore, half of studies supported coping enhancement as a mediator through which CBT and CBT-based interventions are effective with AUD/SUD. There may be preliminary support for this mechanism, but uniqueness, or specificity to CBT process has not been conclusively demonstrated.

Craving, affect regulation, or stress.

While central to well-established models of addiction etiology, only a handful of studies examined drug craving, general stress, or affect or stress regulatory processes. One craving study tested and demonstrated mediation for CBI participants in the COMBINE sample (Subbaraman, Lendle, van der Laan, Katsukas, & Ahern, 2013). Specifically, the CBI only and the CBI plus naltrexone conditions differentially reduced craving in comparison to the medication management conditions, and these reductions acted as statistical mediators of abstinence outcomes at 12-month follow-up. In other studies, CBT or CBT-based interventions failed to differentially impact affect regulation among depressed participants with SUD (Glasner-Edwards et al., 2007) and to dampen emotional distress among AUD participants in contrast to case management (Litt et al., 2018). Unfortunately, craving, stress, and affect regulation have been understudied in the CBT literature, and craving in particular may be a promising target to consider in future studies.

Other mediator variables.

The remaining between-condition studies considered 12-step and social network-related variables. When studies directly compared CBT or CBT-based programs to 12-step programs, a path results showed non-significant differences (Brown et al., 2002) or less 12-step adoption/affiliation (Glasner-Edwards et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2006). Moreover, CBT-based interventions have not been found to differentially relate to social support or network changes in contrast to TSF (Glasner-Edwards et al., 2007) and case management (Litt et al., 2018). Therefore, while social network changes would certainly be of interest to a CBT-based model of change, we find no evidence that these mechanisms are CBT-specific.

Within-condition studies

Self-efficacy.

The final group of models all entailed tests of statistical mediation, within-condition, among COMBINE Study participants. First, Hartzler, Witkiewitz, Villarroel, & Donovan (2011) showed that therapeutic bond, a sub-scale of the working alliance inventory (Horvath & Greenberg, 1986) was associated with enhanced self-efficacy and subsequent improvements in follow-up drinking frequency, consequences, and global symptom severity. This path and mediation model was supported in the CBI-only condition and not within the CBI conditions that included medication and medication management. Second, Witkiewitz, Donovan, and Hartzler (2012) demonstrated mediation for CBI participants who received a drink refusal module, whereby self-efficacy was higher, and this related to reduced drinking frequency at 12-month follow-up. Therefore, when within-versus between-condition models are conducted, support for self-efficacy as a mediator of CBI effect has been demonstrated. This suggests that while self-efficacy might not be uniquely implicated in CBT or CBT-based interventions, it is a process relevant within CBI.

Mediation study quality review

We found that there is encouraging progress in methodology used in studies when compared to the body of literature examined in Morgenstern and Longabaugh’s (2000) review. Considering each column in Table 2 (left to right, respectively), all studies included some theoretical formulation to justify mediation and/or path model aims. Most often, the etiological work of Bandura (e.g., 1969) was cited. However, authors also considered the conceptual models of the intervention conditions themselves (e.g., Annis, 1986; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985), including those justifying a differential process in contrast to some form of experimental control. The majority of studies (73%) also moved beyond path analysis to formal mediation testing, and of those studies all except one used analytic methods considered the standard of practice (e.g., product of coefficients, non-parametric confidence intervals). The one study that did not use standard methods, used the method that was essentially standard at the time (Johnson et al., 2006; causal steps). However, only two studies (Kiluk et al., 2017; Litt et al., 2018) reported some form of power analysis and even these studies stated only that the analysis was powered to detect a certain level of effect (i.e., no detailed analysis was provided). For psychometric reporting, 73% of studies reported acceptable psychometric data for the measures utilized. The large majority of studies also conducted temporally-lagged path models, and this was the case particularly for the b, mediator to outcome, path (94%). Even with regard to a temporal a path, a pre-to-post change score or baseline adjusted outcome model for the mediator was standard. As noted previously, a between-condition path model was also typical (87%), although not all of these studies contrasted the CBT condition with what could be considered a “clearly weaker” comparator (69%), in the sense that the comparator should have no effect on the purported mechanism of interest. Finally, an acceptable majority of studies (60%) included some form of covariate adjustment in the b path model, as defined by an assessment of possible confounding outcome predictors and their control in a multivariate analysis.

Discussion

In this systematic review, 15 secondary analyses of 10 independent trials were examined for evidence of key mechanisms of CBT or CBT-based intervention effects. The results showed that while the methodology has progressed, the evidence is only somewhat more conclusive than in the seminal review by Morgenstern and Longabaugh (2000). Specifically, we found support for increases in coping skills as a mediator or moderated-mediator in four of eight studies reviewed (Kiluk et al., 2010; Litt et al., 2018; Roos et al., 2017; Witkiewitz et al., 2018). For self-efficacy, mediation was supported within CBI (Hartzler et al., 2011; Witkiewitz et al., 2012), but not in six studies that examined self-efficacy as a mediator uniquely relevant to CBT in contrast to another intervention condition. The remaining putative mechanisms considered were a diverse set of theoretically justified variables with one or two studies dedicated to each and little conclusive support. The exception may be reduced craving, and this mediation effect was found in CBI in contrast to a very minimal control (i.e., placebo with medication management; Subbaraman et al., 2013). In what follows, we will consider some potential reasons for the current state of this literature as well as some implications for future research.

Should we emphasize common or unique mechanisms of change in CBT for AUD/SUD?

In the study quality review, all models were deemed well justified on theoretical grounds and a majority considered a between-condition path model of mediator variable effects. A between-condition path model is arguably more rigorous due to stronger conclusions of causality (i.e., randomization) and specificity (i.e., the process occurs in CBT but not its comparator) at the a path (MacKinnon, 2008). In Morgenstern and Longabaugh’s (2000) review, the criterion of a “clearly weaker” control was introduced as a design element to consider when examining mechanisms of intervention effects in the context of clinical trials. However, the authors considered it important to the c path (i.e., intervention to outcome) in their modified causal steps assessment. While forward thinking at the time, acceptance of non-differential efficacy between ‘bona-fide’ treatments is now common in the psychotherapy and addictions literature (Imel, Wampold, Miller, & Fleming, 2008; Wampold, 2001; Wampold & Imel, 2015). In the present review, this criterion was instead used in relation to the a path. That is, a fair between-condition test requires a comparator that should have no effect on the purported mechanism of interest.

Between-condition studies that were judged well-justified theoretically due to a differential emphasis on a specific mechanism in one intervention’s conceptual model in contrast to another, could still be judged to have an untenable a path (i.e., a “no” status for a clearly weaker control). This apparent contradiction most often occurred in relation to 12-step based treatments where empirical hind-sight has shown these interventions also result in changes in self-efficacy and coping skills (Kelly, Magill, & Stout, 2009). In the present review, CBT participants reported greater self-efficacy or coping than 12-step participants approximately half of the time (i.e., Brown et al., 2002; Roos et al., 2017 [conditional model]). Further, in the Litt and colleagues (2003) study, the authors ultimately collapsed across conditions and supported a mediation model for motivation, self-efficacy, and subsequent coping across both CBT and interactional group therapy. Given what we know about non-differential efficacy between evidence-based interventions as well as what appears to be emerging evidence for common processes of change as well, it may be time to revise our theoretical models to accommodate attention to cross-cutting mechanisms of change.

Should we emphasize conditional or unconditional process models in CBT for AUD/SUD?

While emerging evidence points to non-differential, or cross-cutting mechanisms, as one possible reason for the current findings, we do not suggest that all evidence-based AUD/SUD interventions work exactly the same way. More likely, their processes are more similar than they are different. An additional explanation may be the presence of conditional, rather than unconditional, mechanisms of change. In other words, certain intervention ingredients are important or show mechanistic effects only for certain patient populations. In the present review, a majority of supported path or mediation models were some form of conditional model (i.e., Brown et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2006; Kiluk et al., 2017; Litt et al., 2018; Maisto et al., 2015; Roos et al., 2017). Path or mediator effects held at certain levels of therapeutic alliance (Maisto et al., 2015), patient severity or coping capacity (Kiluk et al., 2017; Roos et al., 2017), and for certain types of outcomes (e.g., Litt et al., 2018) and this speaks both to the complexity of individual change and the difficulty in supporting a broadly generalizable process model of intervention effect. Therefore, given the range of supported conditional models found here, considerations of when mechanisms of CBT may or may not be most beneficial is certainly an area in need of further study.

Toward a Science of Behavior Change: Cross-cutting mechanisms, conditional models, and an experimental medicine-based approach

Thus far we have suggested that cross-cutting mechanisms and conditional mechanisms are two likely reasons for difficulty in supporting path or mediation models of CBT and CBT-based intervention effects. A recommendation is to consider mechanisms that have historically been emphasized in the CBT conceptual model as common mechanisms in a broader model of behavior change. This recommendation is in line with the SOBC framework that is not only trans-theoretical, as suggested here, but also trans-diagnostic across classes of disease and/or risk behaviors. In this review, variability in methodology was substantial, particularly regarding conceptualization and measurement of the mediators of interest. In the SOBC initiative, a central goal is to develop and refine a set of common, valid and reliable ‘assays’ of behavioral targets that are measureable, malleable, and play a role in producing behavior change (Neilson et al., 2018). The framework emphasizes three broad classes of targets, which are self-regulation, stress resilience/reactivity, and interpersonal/social processes. Given the challenges demonstrated in this review in identifying clear mediation using traditional approaches, we recommend conceptual and methodological re-formulation for future mediation studies of CBT.

First, we recommend clear and reliable specification of mediators in line with the SOBC framework. In the case of CBT, this may include moving away from self-reported measures of self-efficacy toward observational measures of behavioral coping (Kiluk, 2015; cf. Magill, Kiluk, McCrady, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 2015) and measures of neurocognitive changes in basic processes associated with addiction (Volkow, Koob, & McLellan, 2016; Kwako et al., 2019). In fact, the neuroscience of behavior therapies is a highly promising area of study (Potenza, Sofuoglu, Carroll, & Rounsaville 2011; Chung et al., 2016) and an intervention that emphasizes learning, cognitive control, and regulation of affect or other stressors might have some unique cognitive benefits over other modalities. Regardless of the mechanistic construct of interest, we underscore the SOBC recommendation that a core set of validated assays/measures be incorporated in future research, which should in turn aid our ability to synthesize future studies as well as to distinguish theory failure from measurement failure.

The SOBC framework argues that future clinical research must be specifically designed to test putative mechanisms of behavior change therapies (Neilson et al., 2018), which was a design component virtually absent in the CBT studies reviewed. Historically, tests of mediating processes have not been the primary aims of clinical trials, and therefore, methodological focus on key issues such as appropriate control conditions, adequate statistical power, and theoretically-driven temporal resolution of key constructs has been lacking (Magill & Longabaugh, 2013). Another factor that may obfuscate our ability to determine the extent to which CBT actually impacts the intended mechanistic target (a path) is the complex, multicomponent nature of most CBT protocols. Therefore, future studies should adopt an experimental medicine-based approach, where intervention components are theoretically and conceptually linked to intended mechanistic targets, and that linkage should be tested in the context of the clinical trial (Neilson et al., 2018). In this sense, dismantling studies (Morgenstern, Kuerbis, Amrhein, Hail, Lynch, & McKay, 2012; Morgenstern, Kuerbis, Houser, Levak, Amrhein, Shao, & McKay, 2017), intervention optimization methods (Collins, Murphy, & Strecher, 2007) and utilization of technology-delivered interventions that offer a systematic and controlled level of exposure to CBT ingredients (Carroll et al., 2008) may hold the greatest promise for future research.

Strengths, Limitations, and Conclusions

This review sought empirical support for a clinical process model of CBT intervention effect when tested with adults with AUD/SUD. In an approach intended to reduce bias in reporting, only studies containing both a and b path results were included. This approach has strengths and limitations. With respect to strengths, it is a conservative approach with a narrow, and thus cohesive, emphasis on mediation research in CBT for AUD/SUD. The limitations may be that it is a less comprehensive view than if the full universe of secondary outcomes in CBT clinical trials was reviewed. Another limitation is our box-score approach summarizing findings based on p values instead of providing aggregate estimates of a, b, and ab path effect sizes. In this regard the knowledge found here suffers from the same statistical limitations that may have existed within the primary study sample (e.g., low power to detect mediation effects). Finally, despite efforts to achieve clinical and/or methodological homogeneity in the studies reviewed, this literature was highly variable, including the versions of CBT examined, which may have hindered our capacity to draw clear clinical implications for CBT practice with AUD/SUD.

With these considerations in mind, the most promising candidate mechanism observed was changes to self-regulatory coping skills although we do caution against an overly simplistic model. The current review also suggests there are common mechanisms across the therapies that have been contrasted with CBT and that the most conclusive mediation models have been conditional on some patient or contextual factor. If we are to move toward a more unified, mechanistic understanding of intervention-facilitated behavior change, including change via CBT, important work on theory, measurement/assay development, and targeted experimental tests are clearly needed. The goal has always been to improve the training and quality of addictions care, but in the case of complex interventions such as CBT, some conceptual and methodological re-formulation may first be warranted.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This systematic review investigated nearly 30 years of mediation research on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for alcohol or other drug use disorders (AUD/SUD).

A systematic search yielded 15 studies examining a statistical path model or mediation tests of theory-driven mechanisms of CBT for addictions.

Mediation study quality review showed good methodological progress in this literature, including use of a theoretical rationale, appropriate statistical techniques, and meaningful temporal precedence in the majority of studies reviewed.

The most promising candidate mechanism was changes to self-regulatory coping skills, although the specificity of this process to CBT or CBT-based treatment remains unclear.

The current review also suggests that the most conclusive mediation models have been conditional on some patient or contextual factor (i.e., moderated-mediation).

Adopting guidelines from the Science of Behavior Change Framework, we recommend future work on theoretical refinement, measurement/assay development, and targeted experimental tests of putative CBT mechanisms.

Acknowledgement:

This research is supported by #026006 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, awarded to Molly Magill. Support for consultation and manuscript preparation provided by #021157 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, awarded to J.S. Tonigan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no competing interests to report.

References

* references marked with an asterisk were included in the systematic reivew.

- Annis HM (1986). A relapse prevention model for treatment of alcoholics In Miller WR & Heather N (Eds.), Treating Addictive Behaviors. Applied Clinical Psychology (Vol. 13). Boston, MA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, … & Zweben A (2006). Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: The COMBINE study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 295(17), 2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1969). Principles of Behavior Modification. Oxford, England: Holt, Reinhart, & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brown TG, Seraganian P, Tremblay J, & Annis H (2002). Process and outcome changes with relapse prevention versus 12-step aftercare programs for substance abusers. Addiction, 97(6), 677–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM (1996). Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: A review of controlled clinical trials. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 4(1), 46–54. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.4.1.46 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, Nuro KF, … & Rounsaville BJ (2008). Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: A randomized trial of CBT4CBT. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(7), 881–888. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Kiluk BD (2017). Cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders: Through the stage model and back again. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 847–861. doi: 10.1037/adb0000311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Onken LS (2005). Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(8), 1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless D, & Hollon S (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Noronha A, Carroll KM, Potenza MN, Hutchison K, Calhoun VD, … & Feldstein Ewing SW (2016). Brain mechanisms of change in addictions treatment: Models, methods, and emerging Findings. Current Addiction Reports, 3(3), 332–342. doi: 10.1007/s40429-016-0113-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, & Strecher V (2007). The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(5 Suppl), S112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito EE, Dong G, Kober H, Xu J, Carroll KM, & Potenza MN (2017). Functional neural changes following behavioral therapies and disulfiram for cocaine dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(5), 534–547. doi: 10.1037/adb0000298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Glasner-Edwards S, Tate SR, McQuaid JR, Cummins K, Granholm E, &Brown SA (2007). Mechanisms of action in integrated cognitive-behavioral treatment versus twelve-step facilitation for substance-dependent adults with comorbid major depression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(5), 663–672. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hartzler B, Witkiewitz K, Villarroel N, & Donovan D (2011). Self-efficacy change as a mediator of associations between therapeutic bond and one-year outcomes in treatments for alcohol dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 269–278. doi: 10.1037/a0022869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, & Green S (2011). Handbook For Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. In. Retrieved from http://handbook.cochrane.org

- Horvath AO, & Greenberg LS (1986). The development of the Working Alliance Inventory In Greenberg LS & Pinsoff WM (Eds.), The Psychotherapeutic Process: A Research Handbook (pp. 529–556). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner RB, & Tonigan JS (2007). The search for mechanisms of behavior change in evidence-based behavioral treatments for alcohol use disorders: Overview. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(10 Suppl), 1s–3s. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Wampold BE, Miller SD, & Fleming RR (2008). Distinctions without a difference: Direct comparisons of psychotherapies for alcohol use disorders. Psychology ofAddictive Behaviors, 22(4), 533–543. 10.1037/a0013171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, & Wang MC (1999). Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 563–570. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Johnson JE, Finney JW, & Moos RH (2006). End-of-treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral treatment and 12-step substance use treatment programs: Do they differ and do they predict 1-year outcomes? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31(1), 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Barba R, Rubio Valladolid G, Martinez-Gras I, Alvarez-Alonso MJ, Ponce Alfaro G, Fernandez A, … & Jimenez-Arriero MA (2015). Changes on the modulation of the startle reflex in alcohol-dependent patients after 12 weeks of a cognitive-behavioral intervention. European Addiction Research, 21(4), 195–203. doi: 10.1159/000371723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Nock MK (2003). Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(8), 1116–1129. doi: 10.11n/1469-7610.00195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Magill M, & Stout RL (2009). How do people recover from alcohol dependence? A systematic review of the research on mechanisms of behavior change in Alcoholics Anonymous. Addiction Research & Theory, 17(3), 236–259. doi: 10.1080/16066350902770458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Kiluk BD, DeVito EE, Buck MB, Hunkele K, Nich C, & Carroll KM (2017). Effect of computerized cognitive behavioral therapy on acquisition of coping skills among cocaine-dependent individuals enrolled in methadone maintenance. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 82, 87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kiluk BD, Nich C, Babuscio T, & Carroll KM (2010). Quality versus quantity: Acquisition of coping skills following computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction, 105(12), 2120–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03076.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Schwandt ML, Ramchandani VA, Diazgranados N, Koob GF, Volkow ND, … & Goldman D (2019). Neurofunctional domains derived from deep behavioral phenotyping in alcohol use disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 176(9), 744–753. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18030357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Hubscher M, Moseley GL, Kamper SJ, Traeger AC, Mansell G, & McAuley JH (2015). How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies in people with back and neck pain. Pain, 156(6), 988–997. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Litt MD, Kadden RM, Cooney NL, & Kabela E (2003). Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 118–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Litt MD, Kadden RM, & Tennen H (2018). Treatment response and non-response in CBT and Network Support for alcohol disorders: Targeted mechanisms and common factors. Addiction, 113(8), 1407–1417. doi: 10.1111/add.14224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Magill M, Morgenstern J, & Huebner RB (2013). Mechanisms of behavior change in treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorders In McCrady BS & Epstein EE (Eds.), Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook (2nd ed., pp. 572–596). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Kiluk BD, McCrady BS, Tonigan JS, & Longabaugh R (2015). Active ingredients of treatment and client mechanisms of change in behavioral treatments for alcohol use disorders: Progress 10 years later. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(10), 1852–1862. doi: 10.1111/acer.12848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, & Longabaugh R (2013). Efficacy combined with specified ingredients: A new direction for empirically supported addiction treatment. Addiction, 108(5), 874–881. doi: 10.1111/add.12013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, & Ray L (2009). Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(4), 516–527. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Ray L, Kiluk BD, Hoadley A, Bernstein M, Tonigan JS, & Carroll KM (2019). Cognitive behavioral therapy and relapse prevention for alcohol and other drug use disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Maisto SA, Roos CR, O’Sickey AJ, Kirouac M, Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, & Witkiewitz K (2015). The indirect effect of the therapeutic alliance and alcohol abstinence self-efficacy on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems in Project MATCH. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(3), 504–513. doi: 10.1111/acer.12649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell G, Kamper SJ, & Kent P (2013). Why and how back pain interventions work: What can we do to find out? Best Practice & Research: Clinical Rheumatology, 27(5), 685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA , & Gordon JR (Eds.). (1985). Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Mastroleo NR, & Monti PM (2013). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for addictions In McCrady BS & Epstein EE (Eds.), Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of Behavior Change Satellite Committee. (2018). Novel approaches to the study of mechanisms of behavior change in alcohol use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(2), 159–162. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Brown JM, Simpson TL, Handmaker NS, Bien TH, Luckie LF, … & Tonigan JS (1995). What works? A methodological analysis of the alcohol treatment outcome literature In Hester RK & Miller WR (Eds.), Handbook ofAlcoholism Treatment Approaches: Effective Alternatives (pp. 12–44). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, & Stroup DF (1999). Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials: The QUORUM statement. Lancet, 354, 1896–1900. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Amrhein P, Hail L, Lynch K, & McKay JR (2012). Motivational interviewing: A pilot test of active ingredients and mechanisms of change. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 859–869. doi: 10.1037/a0029674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Houser J, Levak S, Amrhein P, Shao S, & McKay JR (2017). Dismantling motivational interviewing: Effects on initiation of behavior change among problem drinkers seeking treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31, 751–762. doi: 10.1037/adb0000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, & Longabaugh R (2000). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence: A review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiction, 95(10), 1475–1490. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951014753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L, Riddle M, King JW, Aklin WM, Chen W, Clark D, … & Weber W (2018). The NIH Science of Behavior Change Program: Transforming the science through a focus on mechanisms of change. Behavior Research and Therapy, 101, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, Sofuoglu M, Carroll KM, & Rounsaville BJ (2011). Neuroscience of behavioral and pharmacological treatments for addictions. Neuron, 69(4), 695–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. (1997). Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55(1), 7–29. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Roos CR, Maisto SA, & Witkiewitz K (2017). Coping mediates the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol use disorder among out-patient clients in Project MATCH when dependence severity is high. Addiction, 112(9), 1547–1557. doi: 10.1111/add.13841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sandahl C, Gerge A, & Herlitz K (2004). Does treatment focus on self-efficacy result in better coping? Paradoxical findings from psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral group treatment of moderately alcohol-dependent patients. Psychotherapy Research, 14(3), 388–397. doi: 10.1093/ptr/kph032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Subbaraman MS, Lendle S, van der Laan M, Kaskutas LA, & Ahern J (2013). Cravings as a mediator and moderator of drinking outcomes in the COMBINE study. Addiction, 105(10), 1737–1744. doi: 10.1111/add.12238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS). (2018). Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- *Sugarman DE, Nich, & Carroll KM (2010). Coping strategy use following computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 689–695. doi: 10.1037/a0021584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, & McLellan AT (2016). Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363–371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1511480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE (2001). The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Model, Methods and Findings. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE , & Imel ZE (2015). The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evicence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- *Witkiewitz K, Donovan DM, & Hartzler B (2012). Drink refusal training as part of a combined behavioral intervention: Effectiveness and mechanisms of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(3), 440–449. doi: 10.1037/a0026996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Witkiewitz K, Roos CR, Tofighi D, & Van Horn ML (2018). Broad coping repertoire mediates the effect of the combined behavioral intervention on alcohol outcomes in the COMBINE study: An application of latent class mediation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(2), 199–207. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.