Abstract

Patients with Stage I gastric cancer experience decreased postgastrectomy quality of life (QoL) despite the excellent surgical outcomes. We need to find foundational data required to develop effective nursing care plans designed to improve their QoL. This study examined QoL of patients with Stage I gastric cancer over time following gastrectomy and the effects of QoL subdomains on the patients' overall QoL over time after surgery. Data were collected from 138 patients with Stage I gastric cancer who had undergone gastrectomy within the previous 3 years. Data were classified into 3 groups according to the length of postsurgery time: 12 months or less (Group 1), 13–24 months (Group 2), and 25–36 months (Group 3). A confirmatory factor analysis was performed to examine the effects of QoL subdomains. Quality of life of patients with Stage I gastric cancer improves over time following gastrectomy. Postoperative physical symptoms influenced QoL most in Group 1 patients, whereas physical well-being and emotional well-being were the highest contributors to QoL in Groups 2 and 3, respectively. Nursing interventions must be tailored to meet the particular needs of patients at each period of recovery in order to improve QoL of patients with Stage I gastric cancer after a gastrectomy.

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (Jemal & Torre, 2018) and is one of the most common cancers in Korea (Jung, Won, Kong, & Lee, 2018). Early detection of gastric cancer is increasing, supported by higher rates of health checkups and Korea's National Cancer Screening Project (Song, Lee, & Kang, 2015). As a result, the proportion of patients with Stage I cancer undergoing gastrectomy has grown steadily.

Background

Gastric cancer can be classified in four stages (Stages I–IV) according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor–node–metastasis (AJCC TNM) staging criteria (Edge et al., 2010). According to the classification, when tumor invades under the stomach submucosa without regional lymph nodes metastasis, it is classified as Stage Ia. In cases where the tumor invades under the submucosa of the stomach with one to two regional lymph nodes, or tumor invades the muscularis propria regional lymph nodes as metastasis, it is classified as Stage Ib (Washington, 2010). Both cases are classified as Stage I.

In Stage I gastric cancer, the most common treatment is radical resection involving a gastrectomy and a lymphadenectomy, and follow-up treatment after this surgery is unnecessary (Lee et al., 2014). According to recent findings, patients with Stage I gastric cancer who undergo a radical resection have a 5-year survival rate of 89% or higher (Kim, Seo, Lee, Song, & Park, 2017). However, despite excellent treatment outcomes due to early detection, patients with Stage I gastric cancer can experience various physical symptoms following gastrectomy that negatively impact their quality of life (QoL), including premature fullness, low appetite, decreased food intake, nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, reflux, diarrhea, and weight loss (Karanicolas et al., 2013; Park, Chung, Lee, Kwon, & Yu, 2014).

For patients with cancer, QoL is the subjective well-being that patients with cancer perceive regarding their cancer symptoms. Quality of life is a concept that encompasses subject's physical, emotional, social, and functional subdomains of well-being, and each area has a significant influence on overall QoL of patients with cancer (Conroy, Marchal, & Blazeby, 2006). Physical well-being refers to the patient's physical state and any treatment side effects; emotional well-being refers to a patient's psychological state and emotional stability; social well-being refers to a patient's interpersonal relationship with those surrounding him or her; and functional well-being refers to how well the patient is managing work, home, and leisure activities (Kim et al., 2003). So even though patients with Stage I gastric cancer have good treatment results and no other complementary treatment after a successful gastrectomy, they are influenced by their QoL; in fact, QoL measured in patients with Stage I gastric cancer was lower than that of patients with cancer in Stages I–III or not different from those with Stages II–III (Garland et al., 2010; Lee, 2016).

Improving the QoL for patients with gastric cancer after a gastrectomy is now being considered as an important treatment index, along with survival rate. In particular, improving QoL for Stage I gastric cancer survivors is critically important because these patients are expected to recover faster and return to society sooner than other stage gastric cancer patients (Karanicolas et al., 2013; Song, Kang, Hur, & Shin, 2010). Unfortunately, clinical reality falls short of this. Nursing interventions designed to improve the QoL in patients with Stage I gastric cancer are lacking, because interventions are generally concentrated on patients with more advanced stages of cancer who are receiving secondary treatment after surgery.

These patterns suggest that we need to increase our efforts to improve QoL in patients with Stage I gastric cancer through adequate interventions. To achieve this goal, research is needed to identify QoL characteristics following gastrectomy, as well as factors affecting QoL among Stage I gastric cancer survivors. However, these studies are limited, and most studies focus on the QoL and influencing factor analyses in all patients with gastric cancer, regardless of the disease stage (Lee & Son, 2016; Shan, Shan, Morris, Golani, & Saxena, 2015). To provide appropriate nursing care to patients with Stage I gastric cancer following gastrectomy, accurate identification of QoL characteristics at each stage of recovery is critical.

Study Objectives

This study compares the QoL of patients with Stage I gastric cancer over time following a gastrectomy and analyzes the specific effects of the individual well-being subdomains on these patients' overall QoL. Through these efforts, we sought to provide the foundational data required to develop effective nursing care plans designed to improve QoL of patients with Stage I gastric cancer after a gastrectomy.

The specific study objectives are as follows: (1) examine subjects' general characteristics and disease-related characteristics, (2) examine intergroup differences in QoL and QoL subdomains over time since surgery, and (3) examine the effects of QoL subdomains on the patients' overall QoL over time since surgery.

Methods

Study Design and Subjects

We used a descriptive research study design. The study subjects were individuals having undergone a gastrectomy following a Stage I (either Ia or Ib, AJCC TNM, 7th edition) gastric cancer diagnosis at Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center located in the Daegu, South Korea. Patients were receiving regular outpatient care at the hospital. Selection criteria were as follows: (1) individuals who received a gastrectomy less than 3 years prior to the study, whose cancer did not recur or metastasize, and who did not have other types of cancers; (2) individuals who were not receiving other cancer treatments after the gastrectomy, including chemotherapy; and (3) individuals with no history of psychiatric illnesses affecting QoL.

We took into account previous findings indicating that QoL tends to improve significantly with time and that the influence of gastrectomy on QoL is almost lost at 3 years following surgery (Lee, 2016; Song et al., 2010). Therefore, only patients with Stage I gastric cancer who had undergone gastrectomy within the previous 3 years were selected for participation. It is known that the various physical postgastrectomy symptoms experienced by patients are greatly improved after 1 year, and so subjects were classified into three groups: Group 1, who were postgastrectomy for 12 months or less, Group 2, who had undergone surgery between 13 and 24 months prior, and Group 3, who were 25–36 months postgastrectomy. Because “N” should be 20 times greater than the estimated parameter value (Bae, 2011)—in this case the five subdomains of the Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy—Gastric (FACT-Ga) v. 4 (FACIT.org, 2010)—100 subjects were needed. Ultimately, 150 subjects were recruited to account for attrition possibilities. Twelve of the subjects were excluded because of unfinished questionnaires, and hence 138 subjects were selected for the final analysis.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center (IRB No. 2014-12-022) before commencing research. All subjects were informed of the study's purpose, as well as their rights to anonymity, confidentiality, and to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Individuals wishing to participate provided written consent.

Study Tools

General Characteristics and Disease-Related Characteristics

Subjects' general characteristics were surveyed including age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, economic level, and number of comorbidities. Surveyed disease-related characteristics included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, gastrectomy type, surgical approach, and weight loss rate after surgery (%).

Quality of Life

The FACT-Ga scale was used to measure subjects' QoL by incorporating characteristics of patients with gastric cancer into FACT-general QoL measurement scale (FACIT.org, 2010). The FACT-Ga comprises 46 items designed to assess patients with gastric cancer across the four well-being subdomains and gastric cancer symptoms over the previous 7 days. Each item is self-assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4 points); (FACIT.org, 2010; Karanicolas et al., 2013). The sum of each domain's score represents total FACT-Ga scores, which is lowered as the perceived severity of symptoms increases and sense of well-being decreases (FACIT.org, 2010). The scales' reliability at the time of development and during the study were Cronbach's α = 0.90 (Kim et al., 2003) and α = 0.917, respectively.

Data Collection

Data were collected between January and February 2015. Subjects were encouraged to complete the questionnaire on their own as much as possible. For older subjects and those with reading and comprehension difficulties, a researcher provided assistance. The questionnaires took 10 minutes to complete; they were collected on the spot and later anonymized. Other necessary data were collected via an analysis of electronic medical records. The researcher evaluated subjects' performance stratus with the ECOG and measured subjects' body weight using a scale at the outpatient clinic, while subjects completed the FACT-Ga questionnaire.

Data Analysis

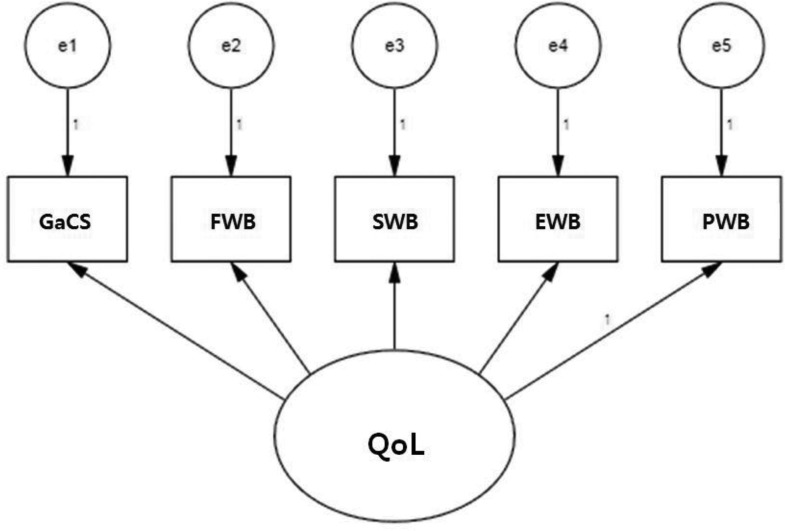

Subjects' general characteristics, disease-related characteristics, and QoL were analyzed for frequency, percentage, average, and standard deviation. Differences in QoL based on subject characteristics and length of time since surgery were analyzed with an independent t test, analysis of variance, and a Scheffe test. In addition, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed to examine the effects of QoL subdomains. The FACT-Ga model was used in the confirmatory factor analysis on the basis of a structural equation model (Figure 1). The model's fit index was calculated, and standardized estimates were examined, having been calculated via a model analysis. Physical well-being was used as the standard to which all other variables were compared, and estimates were compared and analyzed for their influence on QoL while using the standardized path coefficient. The fit was assessed using χ2, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI). Data were analyzed with SPSS WIN 21.0 and Amos 18.0.

FIGURE 1.

Structure equation model of FACT-Ga. EWB = emotional well-being; FWB = functional well-being; GaCS = gastric cancer subscale; PWB = physical well-being; QoL = quality of life; SWB = social well-being.

Results

Group Characteristics and Homogeneity Verification

The study subjects comprised 73 men (52.9%) and 65 women (47.1%), with an average age of 58.21 ± 7.11 years. The general characteristics of all subjects are shown in Table 1. Groups 1–3 were composed of 46 (33.3%), 43 (31.2%), and 49 (35.5%) subjects, respectively. The three groups were homogenous over time following surgery.

TABLE 1. Homogeneity Test of General Characteristics Between Groups.

| Variables | Category | Total n = 138 | Group 1a n = 46 | Group 2 n = 43 | Group 3 n = 49 | χ2/F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.21 ± 7.11 | 58.54 ± 8.50 | 59.81 ± 7.78 | 56.51 ± 4.29 | 2.60 | .078 | |

| Gender | Men | 73 (52.9) | 23 (50.0) | 22 (51.2) | 28 (57.1) | 0.56 | .755 |

| Women | 65 (47.1) | 23 (50.0) | 21 (48.8) | 21 (42.9) | |||

| Spouse | Yes | 109 (79.0) | 34 (73.9) | 34 (79.1) | 41 (83.7) | 1.36 | .506 |

| No | 29 (21.0) | 12 (26.1) | 9 (20.9) | 8 (16.3) | |||

| Education | Middle school or lower | 57 (41.3) | 18 (39.1) | 19 (44.2) | 20 (40.8) | 1.72 | .787 |

| High school | 56 (40.6) | 17 (37.0) | 18 (41.9) | 21 (42.9) | |||

| Higher than college | 25 (18.1) | 11 (23.9) | 6 (14.0) | 8 (16.3) | |||

| Employment | Unemployed | 64 (46.4) | 20 (43.5) | 17 (39.5) | 27 (55.1) | 2.47 | .292 |

| Employed | 74 (53.6) | 26 (56.5) | 26 (60.5) | 22 (44.9) | |||

| Economic status | High | 46 (33.3) | 15 (32.6) | 10 (23.3) | 21 (42.9) | 5.70 | .223 |

| Medium | 71 (51.4) | 22 (47.8) | 25 (58.1) | 24 (49.0) | |||

| Low | 21 (15.2) | 9 (19.6) | 8 (18.6) | 4 (8.2) | |||

| Comorbidities | None | 95 (68.8) | 34 (73.9) | 29 (67.4) | 32 (65.3) | 1.10 | .894 |

| 1–2 | 39 (28.3) | 11 (23.9) | 13 (30.2) | 15 (30.6) | |||

| > 3 | 4 (2.9) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.1) | |||

| ECOG | 0 | 114 (82.6) | 38 (82.6) | 31 (72.1) | 45 (91.8) | 6.99 | .322 |

| 1 | 20 (14.5) | 6 (13.0) | 10 (23.3) | 4 (8.2) | |||

| 2 | 2 (1.4) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 3 | 2 (1.4) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Reconstruction method | Subtotal | 112 (81.2) | 34 (73.9) | 34 (79.1) | 44 (89.8) | 4.09 | .129 |

| Total | 25 (18.8) | 12 (26.1) | 9 (20.9) | 5 (10.2) | |||

| Surgery method | Open | 43 (31.2) | 11 (23.9) | 11 (25.6) | 21 (42.9) | 4.88 | .087 |

| Laparoscopic | 95 (68.8) | 35 (76.1) | 32 (74.4) | 28 (57.1) | |||

| Body weight loss (%) | 12.22 ± 6.90 | 10.93 ± 5.47 | 12.08 ± 6.51 | 13.57 ± 8.22 | 1.77 | .175 |

Note. ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

aGroup 1 = subjects 12 months postgastrectomy or less; Group 2 = subjects 13–24 months postgastrectomy; Group 3 = subjects 25–36 months postgastrectomy. Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

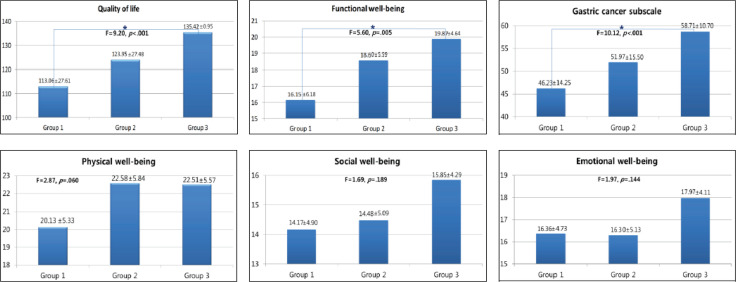

Intergroup Comparisons of QoL and Its Subdomains

The average overall QoL score for all subjects was 124.39 ± 26.88 (Table 2). Group 3 reported significantly higher QoL scores than Group 1 (F = 9.20, p < .001), indicating that QoL tends to increase with length of postsurgery time. Group 3 exhibited significantly higher scores for functional well-being (F = 5.60, p = .005) and the gastric cancer subscale (F = 10.12, p < .001) than Group 1. Scores for physical well-being (F = 2.87, p = .060), social well-being (F = 1.69, p = .189), and emotional well-being (F = 1.97, p = .144) improved as the length of time since surgery increased, though this improvement was not statistically significant (Figure 2).

TABLE 2. Quality of Life and Domain Scores of Study Population.

| Scale/Domain | Score Range | Total |

|---|---|---|

| QoL | 0–184 | 124.39 ± 26.88 |

| GaCS | 0–76 | 52.45 ± 14.40 |

| FWB | 0–28 | 18.23 ± 5.67 |

| SWB | 0–28 | 14.86 ± 4.78 |

| EWB | 0–24 | 16.92 ± 4.69 |

| PWB | 0–28 | 21.73 ± 5.65 |

Note. EWB = emotional well-being; FWB = functional well-being; GaCS = gastric cancer subscale; PWB = physical well-being; QoL = quality of life; SWB = social well-being.

FIGURE 2.

Differences in quality of life and subscales according to groups. Group 1 = subjects 12 months postgastrectomy or less; Group 2 = subjects 12-24 months postgastrectomy; Group 3 = subjects 24-36 months postgastrectomy.

Model Verification

The parameters of the path model to examine the effects of QoL subdomains were estimated, and the modified model's statistical parameters were significant. The path model's fit was estimated as χ2 = 39.22, p < .001, df = 5, GFI = 0.91, NFI = 0.84, CFI = 0.86, which satisfied fit standards.

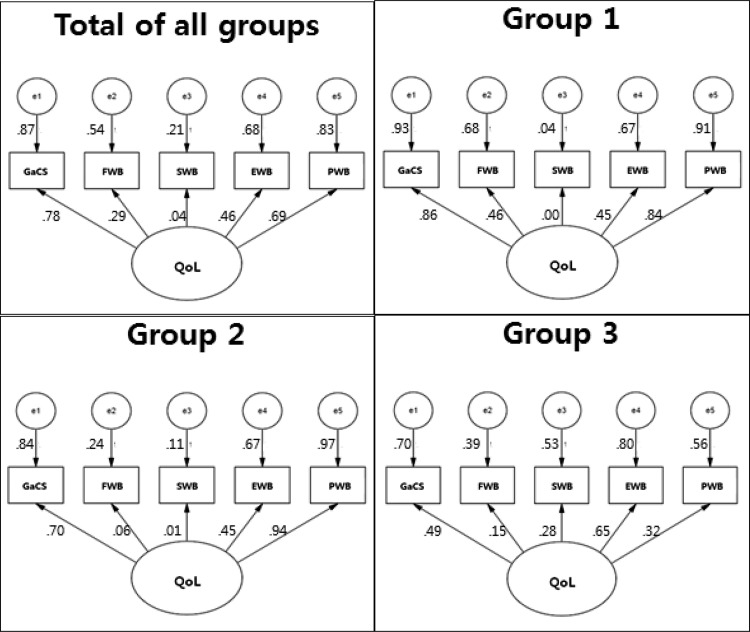

Effects of the QoL Subdomains

The gastric cancer subscale exerted the greatest influence on overall QoL among all subjects (β = .87, p < .001), followed by physical well-being (β = .69, p < .001), emotional well-being (β = .46, p < .001), functional well-being (β = .29, p < .001), and social well-being (β = .04, p < .001). For the individual groups, the gastric cancer subscale also exerted the greatest influence on Group 1 (β = .93, p < .001), whereas Groups 2 and 3 were most affected by physical well-being (β = .97, p < .001) and emotional well-being (β = .80, p < .001), respectively. However, the gastric cancer subscale still has the second largest influence on the QoL in Groups 2 and 3 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Impact of subdomains on quality of life. Group 1 = subjects 12 months postgastrectomy or less; Group 2 = subjects 12-24 months postgastrectomy; Group 3 = subjects 24-36 months postgastrectomy; EWB = emotional wellbeing; FWB = functional well-being; GaCS = gastric cancer subscale; PWB = physical well-being; QoL = quality of life; SWB = social well-being.

Discussion

Patients with Stage I gastric cancer have more than an 89% chance of 5-year survival following a gastrectomy (Kim et al., 2017). Despite this excellent surgical outcome, various physical symptoms accompanying surgery negatively affect QoL (Karanicolas et al., 2013; Park et al., 2014). In fact, some studies report that these patients' QoL after surgery is lower than that of patients with more advanced gastric cancer (Garland et al., 2010). Therefore, we need to increase efforts to improve QoL in patients with Stage I gastric cancer who underwent surgeries through adequate interventions. In this study, patients with Stage I gastric cancer were classified into three groups according to their length of postgastrectomy time. Postgastrectomy QoL was compared among groups, as well as each QoL subdomain's effect on overall QoL over time.

Comparing with a study of QoL of Canadian patients with gastric cancer (Garland et al., 2010), we find that, despite differences in sociocultural background and disease stages in the two study populations, the QoL scores of the Korean subjects were clearly lower than those of their Canadian counterparts across all domains, excluding physical well-being. These results appear to stem from cultural differences between Korean and Canadian societies; because Korean culture emphasizes groups and organizations, others tend to think that health-related issues of patients with cancer may interfere with work and organization performance (Kim, Kim, & Cha, 2001). This leads to social stigma about people with cancer, causing many patients with cancer to leave their jobs and stop participating in other group activities (Kim et al., 2001). This pattern is observed in several patients with Stage I gastric cancer who, due to relatively fast physical recovery after gastrectomy, are highly capable of returning to work. In this vein, a sense of alienation from social and economic participation results in low social and emotional well-being scores among these patients. Furthermore, patients with Stage I gastric cancer may be considered a chronic disease patient. They have to manage and adapt to the physiological and physical changes caused by gastrectomy such as weight loss, dysphagia, reflux, and diarrhea for the rest of their lives (Karanicolas et al., 2013; Park et al., 2014; Wi & Yong, 2012).

Nursing interventions for patients with Stage I gastric cancer who have undergone gastrectomy should be viewed as chronic disease patient care focused on symptom management. In particular, designing nursing interventions that incorporate family and social support known to help overcome the social stigma attached to chronic diseases (Atre, Kudale, Morankar, Gosoniu, & Weiss, 2011) is essential in addressing the social and emotional aspects of recovery. Based on our findings and those of Garland et al. (2010), follow-up studies that examine the effects of sociocultural factors on QoL of patients with gastrectomy are necessary, and interventions that foster a positive sociocultural environment and stunt social stigma should be provided such as family and social support.

The scores of overall QoL, functional well-being, and the gastric cancer subscales improved with postsurgery time, consistent with the findings of previous studies (Karanicolas et al., 2013; Park et al., 2014). Because many side effects of gastrectomy improve over time, overall QoL improves. Nursing interventions at this stage must focus on alleviating any remaining physical side effects of the gastrectomy and improving overall physical function.

Of the QoL subdomains, physical, social, and emotional well-being did not differ significantly among groups. However, Groups 2 and 3 reported a greater level of physical well-being than did Group 1. Group 1 patients reported low physical well-being scores because postgastrectomy symptoms were more acutely experienced during the first 12 months. Over time, these symptoms either subside significantly or patients adapt to the changes (Karanicolas et al., 2013; Park et al., 2014), thus feeling better and reporting a higher physical well-being.

Group 3 reported higher social and emotional well-being than Groups 1 and 2, suggesting a longer time frame for regaining emotional and social well-being than regaining functional or physical well-being after a gastrectomy. Particularly, because social stigma can impede gastrectomy patients' postsurgery social and emotional recovery, it is essential to design nursing intervention programs that promote the social and emotional aspects of recovery for Groups 1 and 2.

According to the results of confirmatory factor analysis in this study, it is essential to provide nursing interventions specifically tailored to address the individual factors influencing patients' QoL at each stage of recovery to improve QoL in patients following gastrectomy. So, for gastrectomy patients who are 1 year postsurgery, nursing interventions focusing on alleviating the various physical symptoms experienced postgastrectomy will be beneficial. Patients who are between 1 and 2 years postsurgery need nursing care focused on improving physical well-being through the management of symptoms that affect patients' daily lives such as tiredness, reduced activity, and so forth. Because emotional well-being has the strongest influence on the QoL of patients between 2 and 3 years postsurgery, nursing interventions for these patients must focus on promoting emotional well-being.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. It was conducted at a single institution and there was no correlation of individual differences in the QoL before gastrectomy. Findings are difficult to generalize because QoL is affected by the culture. Nevertheless, QoL after a gastrectomy is one of the key indices of gastric cancer treatment due to the excellent outcome expected from the surgery, which do not necessitate follow-up treatment. In this sense, this study is meaningful as one of the few studies available examining QoL in patients with Stage I gastric cancer following gastrectomy.

Implications for Practice

Nursing interventions must be tailored to meet the particular needs of patients at each stage of recovery in order to improve QoL for patients with Stage I gastric cancer after a gastrectomy. For patients who were 12 months postgastrectomy or less, nursing interventions should focus on alleviating the various physical postsurgery symptoms. Nursing care for patients with gastric cancer who received surgery 13–24 months prior should focus on improving physical well-being, and interventions for patients whose surgery was between 25 and 36 months prior must focus on promoting emotional well-being.

Conclusion

This study analyzed QoL of patients with Stage I gastric cancer over time after a gastrectomy, as well as the effects of individual QoL subdomains on overall QoL. The results indicate that functional well-being and gastric cancer subscale scores increased with time following surgery, as evidenced by significantly higher QoL scores in Group 3 than in Group 1. For all patients, the subdomain of the gastric cancer subscale exerted the strongest influence on patients' overall QoL. For Group 1, the strongest factor was the gastric subscale, whereas it was physical well-being and emotional well-being for Groups 2 and 3, respectively. Therefore, to improve QoL in patients with Stage I gastric cancer following gastrectomy, nursing interventions must be developed that consider the changes in QoL characteristics over time and the effects of individual subdomains on the overall QoL. Finally, future research involving patients with more advanced gastric cancer or patients with different types of cancer would be beneficial.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Atre S., Kudale A., Morankar S., Gosoniu D., Weiss M. G. (2011). Gender and community views of stigma and tuberculosis in rural Maharashtra, India. Global Public Health, 6(1), 56–71. doi:10.1080/17441690903334240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae B. R. (2011). Structural equation modeling with AMOS 19: Principles and practice. Seoul, South Korea: Chungram Books. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy T., Marchal F., Blazeby J. M. (2006). Quality of life in patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer: An overview. Oncology, 70(6), 391–402. doi:10.1159/000099034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge S. B., Byrd D. R., Compton C. C., Fritz A. G., Greene F. L., Trotti A. (2010). AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- FACIT.org. (2010). Questionnaires. Retrieved from http://www.facit.org/FACITOrg/Questionnaires

- Garland S. N., Pelletier G., Lawe A., Biagioni B. J., Easaw J., Eliasziw M., Bathe O. F. (2010). Prospective evaluation of the reliability, validity, and minimally important difference of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-gastric (FACT-Ga) quality-of-life instrument. Cancer, 117(6), 1302–1312. doi:10.1002/cncr.25556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Torre L. A. (2018). The global burden of cancer. In The American Cancer Society (Ed), The American Cancer Society's Principles of Oncology: Prevention to Survivorship (Chapter 4, pp. 33–44). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. W., Won Y. J., Kong H. J., Lee E. S. (2018). Cancer statistics in Korea: Incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2015. Cancer Research and Treatment: Official Journal of Korean Cancer Association, 50(2), 303–316. doi:10.4143/crt.2018.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanicolas P. J., Graham D., Gönen M., Strong V. E., Brennan M. F., Coit D. G. (2013). Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Annals of Surgery, 257(6), 1039–1046. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828c4a19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Yoo H. J., Kim Y. J., Han O. S., Lee K. H., Lee J. H. (2003). Development and validation of Korean functional assessment cancer therapy-general (FACT-G). The Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 22(1), 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Kim H. W., Cha K. H. (2001). Analyses on the construct of psychological well-being of Korean male and female adults. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 15(2), 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. G., Seo H. S., Lee H. H., Song K. Y., Park C. H. (2017). Comparison of the differences in survival rates between the 7th and 8th editions of the AJCC TNM staging system for gastric adenocarcinoma: a single-institution study of 5,507 patients in Korea. Journal of Gastric Cancer, 17(3), 212–219. doi:10.5230/jgc.2017.17.e23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Kim J. H, Jung H. K., Kim J. H., Jeong W. K., Jeon T. J., Kim H. I. (2014). Clinical practice guidelines for gastric cancer in Korea: An evidence-based approach. Journal of Gastric Cancer, 14(2), 87–104. doi:10.5230/jgc.2014.14.2.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. E. (2016). A structure equation model of quality of life in gastric cancer patients underwent gastrectomy: An examination of the mediating effect of adaptation (Doctoral dissertation, Keimyung University, Daegu, Korea: ). [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. E., Son Y. G. (2016). Research trend of quality of life after gastrectomy among gastric cancer patients in Korea. Asian Oncology Nursing, 16(2), 59–66. doi:10.5388/aon.2016.16.2.59 [Google Scholar]

- Park S. J., Chung H. Y., Lee S. S., Kwon O.K., Yu W. S. (2014). Serial comparisons of quality of life after distal subtotal or total gastrectomy: What are the rational approaches for quality of life management? Journal of Gastric Cancer, 14(1), 32–38. doi:10.5230/jgc.2014.14.1.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B., Shan L., Morris D., Golani S., Saxena A. (2015). Systematic review on quality of life outcomes after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology, 6(5), 544–560. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. K., Lee H. W., Kang D. H. (2015). Epidemiology and screening of gastric cancer in Korea. Journal of the Korean Medical Association, 58(3), 183–190. doi:10.5124/jkma.2015.58.3.183 [Google Scholar]

- Song W. J., Kang K. C., Hur Y. S., Shin S. H. (2010). Comparison of short-term and long-term qualities of life after curative open gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. Korean Journal of Clinical Oncology, 6(2), 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Washington K. (2010). 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 17(12), 3077–3079. doi:10.1245/s10434-010-1362-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wi E. S., Yong J. S. (2012). Distress, depression, anxiety, and spiritual needs of patients with stomach cancer. Asian Oncology Nursing, 12(4), 314–322. [Google Scholar]