Summary

Sugar-containing foods offered at cooler temperatures tend to be less appealing to many animals. However, the mechanism through which the gustatory system senses thermal input and integrates temperature and chemical signals to produce a given behavioral output is poorly understood. To study this fundamental problem, we used the fly, Drosophila melanogaster. We found that the palatability of sucrose is strongly reduced by modest cooling. Using Ca2+-imaging and electrophysiological recordings, we demonstrate that bitter gustatory receptor neurons (GRNs) and mechanosensory neurons (MSNs) are activated by slight cooling, while sugar neurons are insensitive to the same mild stimulus. We found that a rhodopsin, Rh6, is expressed and required in bitter GRNs for cool-induced suppression of sugar appeal. Our findings reveal that the palatability of sugary food is reduced by slightly cool temperatures through different sets of thermally-activated neurons, one of which depends on a rhodopsin (Rh6) for cool sensation.

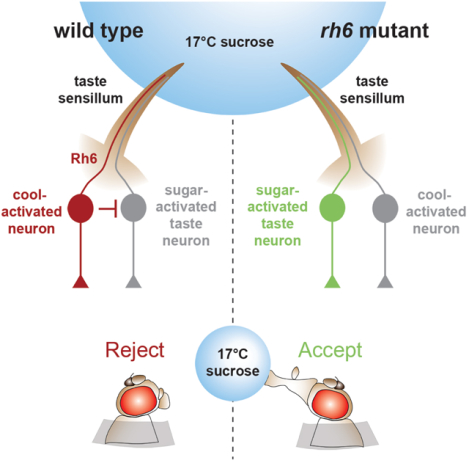

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

Li et al. show that flies tend to reject sweet foods if they are cool. However, sugar taste neurons are not directly suppressed by coolness. Rather, bitter taste neurons and mechanosensory neurons are cool-activated, which reduces feeding. A rhodopsin is required in one class of bitter taste neurons for this behavior, which is light independent.

Introduction

Sweet taste is critical for many animals, as it promotes survival by providing information about whether a prospective food is nutrient rich. Many animals ranging from flies to humans are endowed with receptors tuned to sugars in their taste receptor cells [1]. Activation of the sugar-responsive taste receptor cells promotes the urge to feed, which is accentuated following periods of starvation.

The attraction to sugars is impacted by other food qualities such as texture. The hardness and viscosity of food can have a profound impact on the attractiveness of a sweet dietary option. For example, the soft texture of cotton candy is far more appetizing than the hard sucrose granules from which it is derived, even though the chemical composition of the two forms of sucrose is identical. Over the last few years, discoveries using the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, have revealed mechanosensory neurons and several mechanosensory channels that contribute to the detection of hardness and viscosity [2–4].

In humans, the perception of multiple flavors is also influenced by the temperature of the food [5–9]. Salty and sourness can be increased by cool temperatures, while the subjective evaluation of the sweetness elicited by a variety of sugars, including sucrose, is suppressed by cool temperatures [5–8, 10]. The effects of temperature on sweetness is consistent with experience, as certain desserts such as fruit pies are less delectable when they are consumed directly after removing them from the refrigerator [7]. The sweetness of ice cream is also greater once it melts, although this perception may not be obvious since ice cream melts quickly between the tongue and palate. However, it is unclear if small differences in the food temperature influence palatability in animals such as the fruit fly.

We found that akin to many mammals, flies display a reduced propensity to consume sugar-containing foods that are cooled only a few degrees from room temperature. Surprisingly, this reduced attraction to sugars at slightly cool temperatures was not due to direct suppression of sugar-activated GRNs. Rather, we found that slight cooling caused activation of bitter GRNs and mechanosensory neurons in the fly’s taste organ, the labellum. Elimination of the activities of these neurons prevents the cool-induced suppression of sucrose appeal. We found that a rhodopsin, Rh6, was expressed in bitter GRNs and was required for eliciting cool-mediated reduction in sucrose feeding. Thus, we define a mechanism whereby mildly cool temperatures suppress the attraction to sucrose through an indirect mechanism involving activation of neurons in the taste organ that do not respond to sugar.

Results

Cool food temperature reduces the urge to feed on sugar

To determine whether cool food temperatures alters the urge to feed, we offered flies sugars at 23°C and at slightly lower temperatures (~17—21°C). To ensure that only the food and not their bodies were cooled, we presented sugars to the flies at the end of a narrow temperature-controlled probe (Figures S1A and S1B). The temperature immediately adjacent to the probe is maintained at ≥21.5°C, even at a probe temperature of 17°C (17 ±0.2°C; Figure S1C). To further minimize an effect on body temperature during the assay, we contacted one of the fly’s taste organs very briefly (~0.2—0.4 sec; Figure S1F). These include the main taste organ, the labellum, located at the end of the proboscis, or the leg tarsi. The labella and tarsi are decorated with taste sensilla, which house the dendrites of gustatory receptor neurons (GRNs), such as those that respond to sugars and bitter compounds [1]. To conduct the analysis, we starved control flies (w1118 males) for two hours, and touched the labella or tarsi with a sugar three times with one-minute intervals, and assessed their motivation to feed by recording whether or not they extend their proboscis.

To determine whether the acceptance of sugars was impacted by temperature, we interrogated several sugars at a concentration of 0.5 M. We found that the appeal of all sugars tested was diminished by mild, cool temperatures, although the response to sorbitol was very low even at 23°C (Figure S1G). We focused the remainder of this study on sucrose, which elicited robust responses. When the sucrose solution was at either 23° or 21°C, the flies displayed a proboscis extension response (PER) that approached 100% (Figures 1A, 1B, and 1D, Video S1). During the subsequent offerings, the PER percentage remained high, although it was slightly lower when the sucrose was presented to the labellum (Figures 1E and 1F). When the sucrose was cooled to 17° or 19°C, the PER was significantly reduced (Figures 1C and 1D, Video S2). A 2°C reduction in temperature (21° to 19°C) was also significant (Figures 1D—1F). These differences were more pronounced during the 2nd and 3rd offerings (Figures 1E and 1F). 20°C sucrose caused lower PERs relative to 23°C, but only during the last two offerings (Figures 1E and 1F). Cool temperatures also decreased the attraction to a lower concentration of sucrose (0.1 M; Figure S1H). These data demonstrate that mildly cool temperatures attenuate the palatability of sugar.

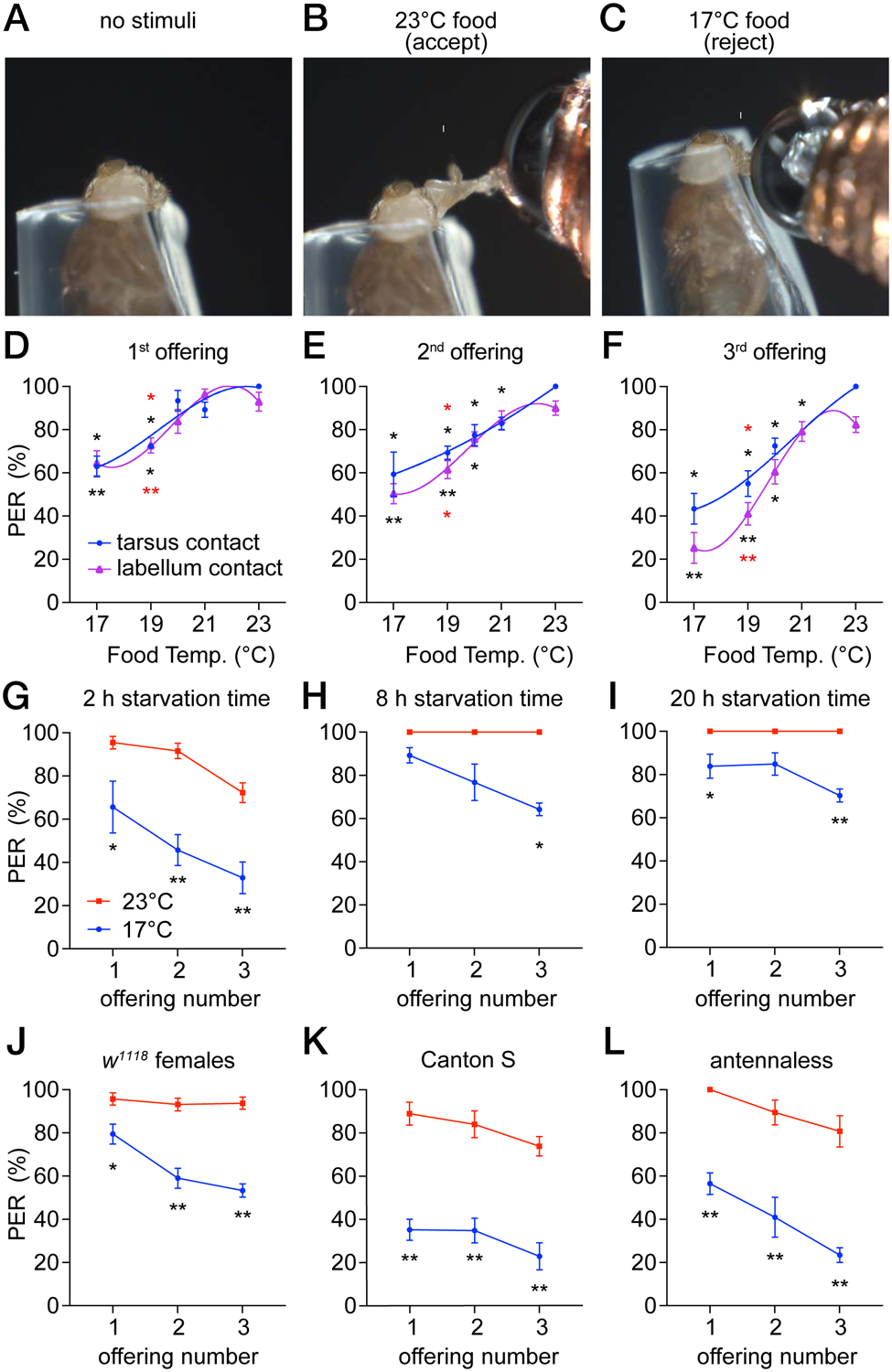

Figure 1. Reduced attraction to cool food.

PER assays using control (w1118) males. The animals were starved for 2 hours unless indicated otherwise. All PER analyses in this study were performed by stimulating the labellum, except for the indicated experiments in D—F that were performed by stimulating tarsi.

(A—C) A fly immobilized in a pipet tip was stimulated on the labellum with a drop of 0.5 M sucrose at the indicated temperature, using a temperature-controlled probe. Figure S1.

(A) Prior to presentation of a food stimulus.

(B) Fly extending its proboscis (arrow) upon stimulation with 23°C sucrose. Video S1.

(C) Fly rejecting sucrose at 17°C. Video S2.

(D—F) PER assays using 0.5 M sucrose at 17° to 23°C. Flies were offered food three consecutive times either on the tarsi (blue) or the labellum (purple). The interval between offerings was 1 minute. A third order polynomial (cubic) equation was used to interpolate the fit curve. Asterisks indicate significant differences between flies stimulated at 23°C (black) or 21°C (red). The labella and tarsi responses were analyzed separately. n=5 trials.

(D) 1st offering.

(E) 2nd offering.

(F) 3rd offering.

(G—I) PER assays to test for impacts of starvation time on cool-induced suppression of attraction to 0.5 M sucrose. Food was offered at either 17°C (blue) or 23°C (red). n=4–5 trials.

(G) 2 hours starvation.

(H) 8 hours starvation.

(I) 20 hours starvation.

(J—L) PER assays testing the effects of sex, the control strain or the antenna on cool-induced suppression of attraction to 0.5 M sucrose. Food was offered at either 17°C (blue) or 23°C (red). We made pairwise comparisons between the 17° and 23° 1st, 2nd, 3rd offerings. Asterisks indicate significant differences between each pair of data.

(J) Females. n=5 trials.

(K) Canton S. n=5 trials.

(L) Antennaless flies. n=6 trials.

Each dot and error bar represents means ±SEM. Each trial includes ≥8 flies. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

To assess whether hunger status affects the impact of temperature on sucrose appeal, we starved the flies for various periods prior to performing the PER assays. We found that when we increased the starvation period from 2 hours to 8 or 20 hours, the flies still displayed a higher PER for 23° over 17°C (Figures 1G—1I). However, the effect of temperature was diminished (Figures 1H and 1I), indicating that longer starvation reduces but does not eliminate the impact of temperature on sucrose attraction.

The preceding experiments were performed using males (w1118 strain). Control female flies (w1118) also showed reduced attraction to cooled sucrose (Figure 1J). This behavior was not specific to the w1118 control strain as Canton S males showed significantly reduced attraction to cool sucrose that was at least as pronounced as w1118 flies (Figure 1K). An appendage extending from the antennae, the arista, contains cool sensing neurons [11]. We surgically removed the antenna and found that the responses to cool food mimicked the responses in intact flies indicating that the thermosensory neurons in the antenna are not involved in thermal taste behavior (Figure 1L).

Lower temperatures can increase fluid viscosity, although the small 2°C temperature drop (21°C versus 19°C) that diminished sucrose appeal was unlikely to be due to a significant change in viscosity. Nevertheless, we measured the viscosities of 0.5 M sucrose at 23° and 17°C and found that they were very similar (Figure S1I; 1.8 versus 1.9 cps). When we added 1% PEG to 0.5 M sucrose, which increased the viscosity from 1.8 to 1.9 centipoise (cps) at 23°C, there was no reduction in the PER (Figure S1J). In addition, evaporation of the drop at the end of the PER probe, which would concentrate the sucrose, does not appear to be an issue. ~30 seconds elapse between addition of the drop of sucrose to the probe, and application of the probe to the proboscis or tarsi. However, even after 2 minutes, there was little change in the drop size (Fig. S1D and S1E).

Distaste for cool food depends on bitter GRNs and mechanosensory neurons

To address whether the activities of sugar GRNs are directly suppressed by cool temperatures we performed in vivo Ca2+ imaging experiments. We assayed the responses of sugar GRNs to modest cooling by expressing the genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor GCaMP6f (UAS-GCaMP6f) [12] under the control of the Gr64f-Gal4, which is expressed in sugar GRNs [13]. To provide a baseline control, we co-expressed the red fluorescent protein, tdTomato (UAS-tdTomato), in the same GRNs (Figures S2A and S2B). We simultaneously imaged most of the sugar GRNs in one layer of the labellum while manipulating the temperature of the sample preparation. We found that decreasing the temperature from ~23° to ~20° or 18°C did not elevate Ca2+ levels in the sugar GRNs, as assessed by monitoring the change in fluorescence relative to the initial fluorescence (ΔF/F0; Figures 2A, 2B and 2I; Video S3).

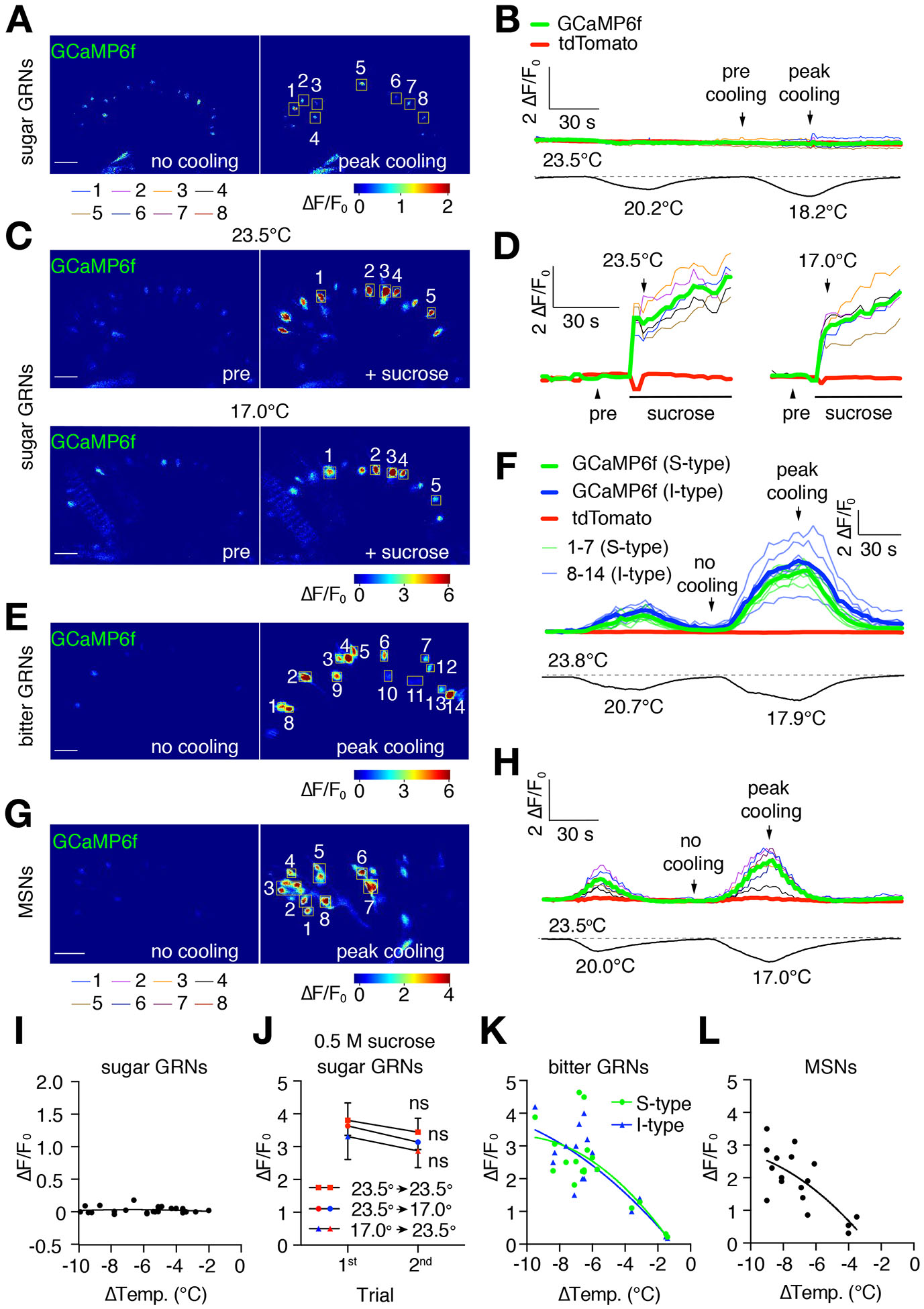

Figure 2. Cooling increases Ca2+ responses in bitter GRNs and MSNs.

Changes in GCaMP6f fluorescence (ΔF/F0) in different classes of neurons in the labellum in response to cooling. UAS-GCaMP6f/+ was expressed under the control of the indicated Gal4 drivers. UAS-tdTomato/+ was co-expressed in the same neurons to serve as a baseline control (see Figure S2 for tdTomato signals). Scale bars in A, C, E, and G represent 20 μm. The regions of interest (ROI) were cells that remained in focus during the entire imaging sequence. See Figures S7D and S7E for setup.

(A, B) GCaMP6f fluorescence (ΔF/F0) in sugar GRNs during cooling. UAS-GCaMP6f/+ and UAS-tdTomato/+ were expressed using the Gr64f-Gal4. Video S3.

(A) GCaMP6f fluorescence (ΔF/F0) prior to cooling and during peak cooling (23.5° and 18.2°C, respectively; left and right panels, respectively). Boxed GRNs are ROI. The cooling regime is shown in (B). A ΔF/F0 color scale is shown.

(B) Traces showing GCaMP6f responses (ΔF/F0) of sugar GRNs to cool temperature stimuli, indicated by the lower temperature trace. Colored thin traces represent each of the 8 sugar GRNs (ROI) indicated in (A). Bold red and green traces denote the average tdTomato and GCaMP6f fluorescence of all cells within the ROI.

(C, D) Cool temperature (e.g. 17°C) does not suppress sucrose-induced GCaMP6f responses in sweet GRNs in the labellum. UAS-GCaMP6f/+ was expressed under control of the Gr64f-Gal4. 0.5 M sucrose was used to stimulate the same labellum at 25°C and 17.0°C. Between the two sucrose applications, the sugar was washed out and the temperature was adjusted. The interval between sucrose applications was 5—10 min. Video S4 for presentation of sucrose at 23° and 17°C. Video S5 for response of sweet GRNs stimulated with sucrose during a cool temperature ramp.

(C) GCaMP6f fluorescence (ΔF/F0) in sugar GRNs 5 sec before (pre) and 5 sec after adding sucrose (+ sucrose) to the same labellum at 23.5°C (top two panels) and at 17.0°C (bottom two panels). The boxed sugar GRNs are ROI. A ΔF/F0 color scale is shown. Some shifting in the orientation of the labellum occurred during the washout of the 23.5°C sucrose. The GRNs (1–5) responding to 17.0°C are the same as those responding to 23.5°C.

(D) Traces showing the GCaMP6f responses (ΔF/F0) to sugar at either 23.5° or 17.0°C. The colored thin traces represent each single sugar GRN (ROI) indicated in (C). The bold red and green bold traces indicate the average tdTomato and GCaMP6f fluorescence.

(E—H) GCaMP6f responses (ΔF/F0) of bitter GRNs and MSNs to cooling. UAS-GCaMP6f/+ and UAS-tdTomato/+ were expressed in bitter neurons and MSNs under control of the: (E, F) Gr66a-Gal4/+, and (G, H) R41E11-Gal4/+. Video S6.

(E) GCaMP6f fluorescence exhibited by bitter GRNs in the absence of cooling (left panel, no cooling, 23.8°C) and during peak cooling (right panel, 17.9°C). The boxed regions in the right panel are the ROI. Cells 1—7 are S-type bitter GRNs, and cells 8—14 are I-type bitter GRNs. The cooling regime is shown in (F). A ΔF/F0 color scale is shown.

(F) Traces showing GCaMP6f responses of bitter GRNs in the presence and absence of cooling. The lower trace displays the temperature changes during the recordings. The colored thin traces represent each single GRN (ROI) indicated in (E). The bold green and blue traces indicate the average GCaMP6f fluorescence in S and I type bitter GRNs respectively, while the bold red trace indicates the average tdTomato fluorescence.

(G) GCaMP6f fluorescence exhibited by MSNs in the absence of cooling (no cooling, 23.5°C; left panel) and during peak cooling (17.0°C; right panel). The boxed regions in the right panel indicate ROI. The cooling regime is shown in (H). A ΔF/F0 color scale is shown. Video S7.

(H) Traces showing GCaMP6f responses of MSNs in the presence and absence of cooling. The lower trace displays the temperature changes during the recordings. The colored thin traces represent each MSN (ROI) indicated in (G). The bold red and green bold traces indicate the average tdTomato and GCaMP6f fluorescence.

(I) Scatter plot of GCaMP6f fluorescence displayed by sugar GRNs to cooling in the absence of sucrose. Each dot represents the average maximum ΔF/F0 from all the GCaMP6f-positive cells in the field following cooling (−2° to −10°C) from the initial temperature of 23°—24°C. Each dot represents the average maximum ΔF/F0 from during one trial at a given temperature. Each sample was subjected to no more than 3 trials. n=14 animals.

(J) GCaMP6f responses (ΔF/F0) of sugar GRNs upon exposure to two consecutive ~40 sec stimulations with 0.5 M sucrose at the indicated temperatures. There were no statistically significant differences between any two consecutive stimuli. Error bars represent means ±SEMs. n=5 animals, nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. ns, not significant. See Figure S3 for dtTomato controls.

(K) Scatter plot of GCaMP6f responses of S- and I-type bitter GRNs to cooling. Each dot represents the average maximum ΔF/F0 from all of the GCaMP6f-positive cells in the field following cooling (−2° to −10°C) from the initial temperature of 23°—24°C. Each dot represents the average maximum ΔF/F0 during one trial at a given temperature. Each sample was subjected to a maximum of 3 rounds of cooling. n=7 animals.

(L) Scatter plot of GCaMP6f responses of mechanosensory neurons to cooling. Each dot represents the average maximum ΔF/F0 from all of the GCaMP6f-positive cells in the field following cooling (−2° to −10°C) from the initial temperature of 23°—24°C. Each dot represents the average maximum ΔF/F0 during one trial at a given temperature. Each sample was subjected to a maximum of 3 rounds of cooling. n=14 animals.

To test whether the activities of sugar GRNs are inhibited by cool temperatures, we stimulated the neurons with 0.5 M sucrose and measured GCaMP6f fluorescence changes. Because we could wash out the sucrose and re-stimulate a labellum, we were able to compare the sucrose-induced GCaMP6f signals of the same GRNs at 23.5° and 17°C. We found that the GCaMP6f changes (ΔF/F0) were similar when we presented sucrose to the labella at 23.5° or 17°C sugar (Figures 2C, 2D, 2J, Video S4). Moreover, we obtained the same results if we reversed the order and first stimulated the labella at 17° and then 23.5°C (Figure 2J). To determine whether the sugar-induced Ca2+ rise was suppressed by transient cooling during prolonged exposure to sucrose, we stimulated the labellum with sucrose at 23.5°C and then continuously monitored GCaMP6f fluorescence while cooling the tissue to 17°C. We compared the results with GRNs held at 23.5°C and found that cooling during stimulation had no significant impact on GCaMP6f activity (Figure S3, Video S5). These data demonstrate that mild cooling does not directly affect the sugar-induced Ca2+ rise.

To determine whether another peripheral neuron in the labellum mediates the suppression of sugar appeal by cool temperatures we inhibited synaptic transmission in different classes of neurons. These include neurons associated with taste sensilla: bitter GRNs, mechanosensory neurons (MSN) and water GRNs. In addition, we inhibited the single multidendritic neuron (md-L) in each bilaterally symmetric labellum that extends dendrites to the base of most taste sensilla [2]. This md-L neuron functions in food texture sensation [2].

To inhibit synaptic transmission, we used the GAL4/UAS system to express the tetanus toxin light chain (UAS-TNT-E) [14] under the control of a set of cell-type specific Gal4 drivers, and performed PER assays. The UAS-TNT-E was effective in blocking synaptic transmission as it nearly eliminated the sugar response when we expressed it under the control of the sugar-GRN driver (Gr64f-Gal4; Figure 3A). As described above, in control flies without any transgene, the cool-suppression at 17°C was more pronounced during the third offering, than during the first and second offerings (Figures 1D—1F and S1G). In the absence of a Gal4 driver, the UAS-TNT-E transgene did not alter the cool-induced suppression of the sucrose-induced PER at 17°C relative to 23°C (Figures 3B, S4A and S4G). When we drove UAS-TNT-E expression in water GRNs using the ppk28-Gal4, there was no reduction in the suppression imposed by cool food (Figures 3C, S4B and S4H). Inhibition of the md-L neuron using the tmc-Gal4 increased the PER to the 0.5 M sucrose at both 23° and 17°C; however, there was still a significant reduction in the PER at 17°C (Figures 3D,S4C and S4I). Nevertheless, because inactivation of md-L neurons causes nearly 100% of the flies to feed on sucrose at 23°C, there is a ceiling effect. Therefore, we conducted additional experiments in which we used 0.1 M sucrose for the 3rd offering instead of 0.5 M sucrose. When we presented md-L inactivated flies with a 3rd offering of 0.1 M sucrose, they showed a similar level of cool suppression of the sugar response (Figure S3M) as did control flies presented with a 3rd offering of 0.5 M sucrose (e.g. Figure 3B).

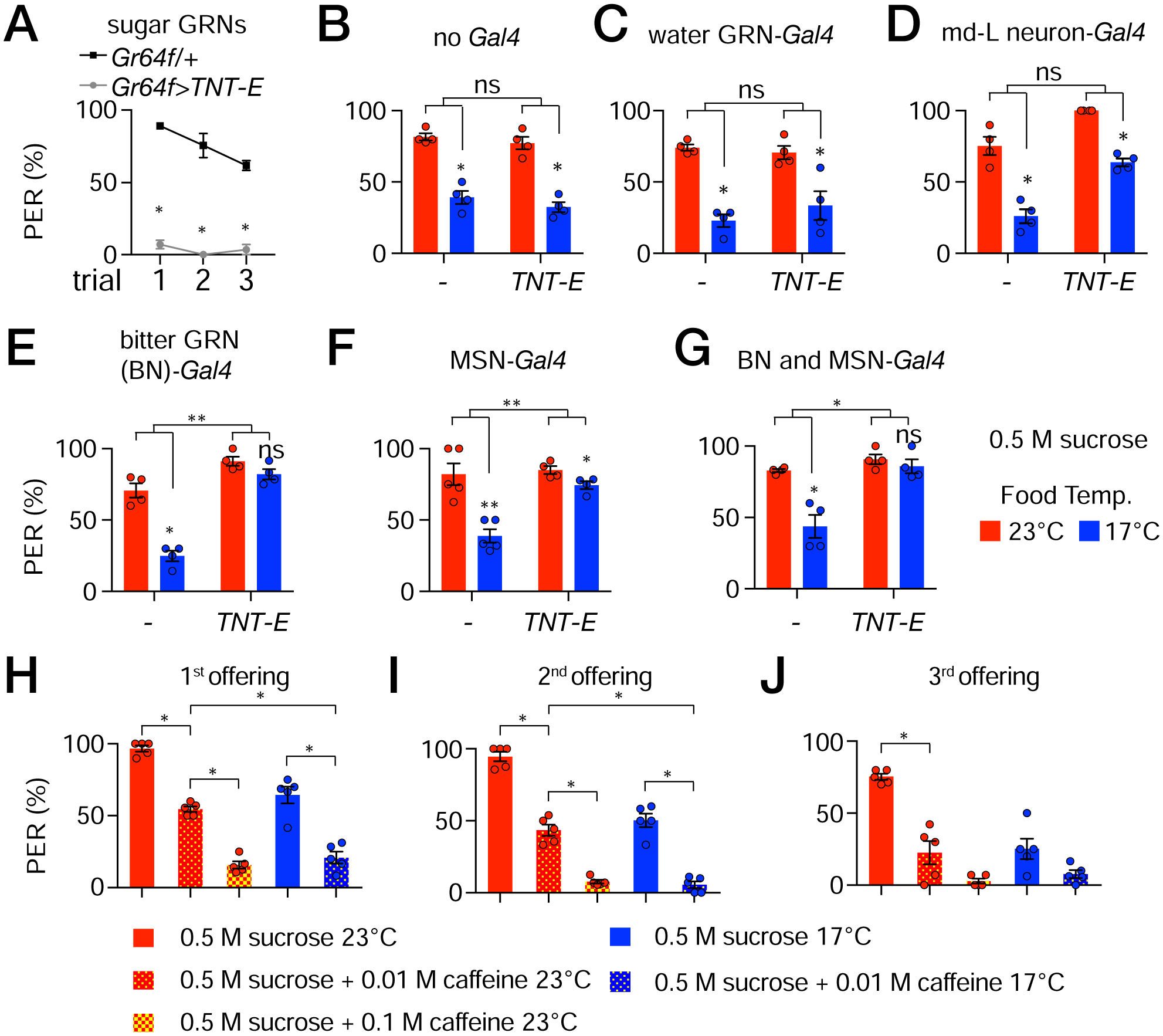

Figure 3. Distaste for cooler food depends on bitter GRNs and MSNs.

PER assays to assess the impact of inhibiting different classes of neurons on the suppression of sugar appeal by cool temperatures. Neurons were inhibited with the tetanus toxin light chain (TNT-E) by expressing UAS-TNT-E under control of the indicated Gal4 lines.

(A) Control to show effectiveness of TNT-E. Expression of UAS-TNT-E in sugar GRNs (Gr64f-Gal4), but not the Gr64f-Gal4 alone, inhibits the response to 0.5 M sucrose. The flies were stimulated with sucrose three times. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. *P<0.05, n=4 trials

(B—G) PER assays in response to 0.5 M sucrose offered at either 23°C (red bars) or 17°C (blue bars) after inhibiting different classes of neurons with UAS-TNT-E. Shown are the results of the 3rd offering (see Figure S4A—S4L for the results of the 1st and 2nd offerings). Nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to analyze statistically significant differences between sucrose offered food at 23° versus 17°C. We used two-way ANOVA to determine whether the temperature-dependent differences (23° versus 17°C) between groups (e.g. UAS-TNT-E alone versus UAS-TNT-E plus the Gal4) were significant. These latter comparisons are indicated by the top brackets in each panel. ns, not significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Error bars represent means ±SEMs.

(B) No Gal4.

(C) Water GRNs (ppk28-Gal4).

(D) md-L neurons (TMC-Gal4).

(E) Bitter GRNs (Gr66a-Gal4).

(F) MSNs (R41E11-Gal4).

(G) Bitter GRNs and MSNs (Gr66a-Gal4 and R41E11-Gal4).

(H—J) PER assay using w1118 flies offered 0.5 M sucrose containing 10 mM or 100 mM caffeine three times. (H) 1st offering. (I) 2nd offering. (J) 3rd offering. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. *P≤0.05. n=5 trials. Each trial includes ≥8 flies.

Unexpectedly, we found that inhibition of synaptic transmission of either bitter GRNs (Gr66a-Gal4) or mechanosensory neurons (R41E11-Gal4) greatly reduced the suppressive effect of 17°C on sugar attraction (Figures 3E, 3F, S4D, S4E, S4J and S4K). In the case of inhibiting MSNs, although the remaining level of cool suppression was very low, it was statistically significant (Figure 3F). When we inhibited synaptic transmission in both bitter GRNs and MSNs, the impact of 17°C on sugar appeal was virtually eliminated (Figures 3G, S4F and S4L). These results indicate that bitter GRNs and MSNs are both required for the cool-induced attenuation of the sugar response.

Given that feeding suppression by cool temperatures is mediated in part by bitter GRNs, we addressed whether lacing 0.5 M sucrose with a bitter compound, such as caffeine, would increase the animals aversion to cool temperatures. In the absence of a bitter compound, 64 ±5% of the animals display a PER when presented with 0.5 M sucrose at 17°C for the first time (Figures 3H—3J). The PER declined to 50 ±4% and 25 ±6% during the 2nd and 3rd offerings (Figures 3H—3J). Addition of 10 mM caffeine to 0.5 M sucrose at 23°C results in a similar PER as sucrose alone at 17°C (Figures 3H—3J; % PER, 1st offering 54 ±2, 2nd offering 43 ±4, 3rd offering 20 ±9). When we included 100 mM caffeine in the 23°C sucrose, the PER was reduced to 16 ±3% at the 1st offering, and nearly eliminated in response to the subsequent offerings (Figures 3H—3J). Upon decreasing the food temperature to 17°C, the 10 mM caffeine was sufficient to elicit similarly low PER levels as 100 mM caffeine plus sucrose at 23°C (Figure 3H). These results indicate that there is an additive effect of bitter on cool-induced aversion, consistent with both stimuli activating bitter GRNs.

Cooling of bitter and mechanosensory neurons increases Ca2+ levels

To provide an initial test as to whether bitter GRNs and MSNs respond to cool temperatures, we assayed for cooling-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+. We expressed UAS-GCaMP6f under the control of the Gr66a-Gal4 and the R41E11-Gal4, which are expressed in bitter GRNs and MSNs, respectively. We found that all bitter GRNs and MSNs labeled by these reporters responded robustly to decreases in temperature (Figures 2E—2H, 2K, 2L, Videos S6 and S7). These include the 20—21 bitter GRNs in S- and I-type sensilla in each bilaterally symmetrical side of the labellum, as well as the MSNs that innervate taste sensilla and taste pegs. The greater the decrease in temperature, the larger the GCaMP6f signals (Figures 2K and 2L). However, cooling did not impact on tdTomato fluorescence (Figures S2C and S2D).

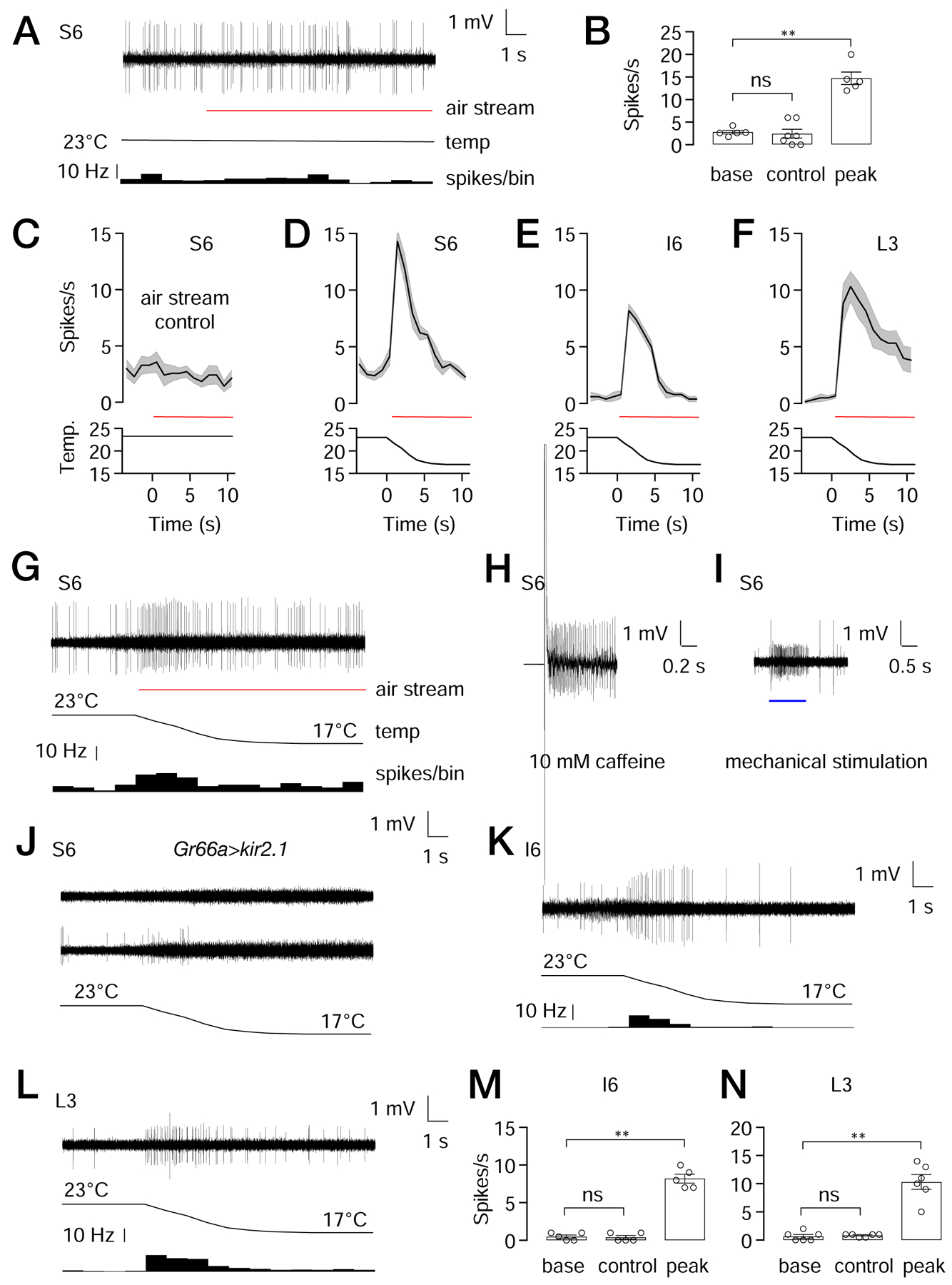

Cooling-induced activation of bitter and mechanosensory neurons

The Ca2+ imaging experiments with GCaMP6f suggests that bitter GRNs and MSNs are stimulated by cool temperatures. However, a change in Ca2+ levels is only a proxy for neuronal activation. An additional limitation of the Ca2+-imaging experiments is that the entire head is submerged in the temperature-controlled bath. Consequently, the entire neurons are exposed to the cooling, rather than just the dendrites. Therefore, to determine directly if cooling activates bitter GRNs and MSNs in the labellum, we modified the tip recording assay to test whether a decline in temperature from 23° to 17°C causes an increased in firing of action potentials. To conduct these experiments, we performed electrophysiological recordings on S, I and L type sensilla using a modified tip recording protocol. We placed a recording pipet containing electrolyte only (30 mM tricholine citrate) over different sensilla, and applied a temperature-controlled air stream to the labellum during the recordings. Prior to initiation of an air stream, there is spontaneous spiking (2.8 ±0.4 Hz; Figure 4B, base). When we applied an air stream to S6 sensilla at a constant temperature (23°C) the firing frequencies were unchanged (2.4 ±0.9 Hz; Figures 4A—4C). Thus, the air stream alone does not alter neuronal activation, indicating that if there was any change in humidity due to the air stream, or slight evaporation of the buffer in the recording pipet, it had no influence on neuronal firing.

Figure 4. Cool-induced action potentials produced in S-, I- and L-type sensilla.

Tip recordings to assay action potentials from the indicated sensilla in response to the indicated stimuli.

(A) S6 sensilla from control flies exposed to an air flow at a constant temperature of 23°C. The trace of action potentials is shown at the top. The red line indicates the application of the air stream. The black line indicates the temperature at the sample. The histogram at the bottom indicates the frequency of action potentials in 1 sec bins.

(B) Statistical summary of bitter spikes recorded from S6 sensilla. The “base” shows the action potentials/sec during the 4 sec prior to application of the constant 23°C air stream (see A). “Control” is the action potentials/sec during the first 2 s after initiation of the constant 23°C air stream (see A). “Peak” is peak action potential frequency obtained with S6 sensilla after initiation of the 23—17°C ramp (see D). n = 5—7 animals per group. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. ns, not significant. ** P<0.01. Bars represent means ±SEM.

(C—F) Average spikes/sec (1 sec bins) produced by the indicated sensilla in response to: (C) constant 23°C air stream, or (D—F) a 23—27°C cooling ramp. The red lines indicate the application of the air streams. The black lines indicate the temperature of the sample. n=5—7 animals.

(G) Trace showing firing of S6 sensilla from control flies in response to cooling.

(H) Trace from control S6 sensilla stimulated with 10 mM caffeine.

(I) Trace from a control S6 sensilla showing mechanical spikes induced by a 20 μm step deflected by the recording electrode (blue line).

(J) Traces showing responses to cooling from S6 sensilla from animals expressing UAS-kir2.1 under control of the Gr66a-Gal4. 9 out of 15 S6 sensilla show no response to cooling (top trace), while the remaining 6 exhibit a low level of mechanical spikes during the cooling from 23°C to 17°C (bottom trace). None of the traces showed the large spikes indicative of bitter GRNs, as observed in (G), indicating that cooling activates bitter GRNs in S6 sensilla.

(K) Trace from control I6 sensilla in response to cooling.

(L) Trace from control L3 sensilla in respond to cooling.

(M, N) Statistical summaries of spikes recorded from (M) I6 sensilla, and (N) L3 sensilla. The “base” shows the action potentials/sec during the 4 sec prior to application of the constant 23°C air stream (see K, L). “Control” displays the action potentials/sec during the first 2 s after initiation of the constant 23°C air stream. “Peak” are the peak action potential frequencies obtained after initiation of the 23—17°C ramp. (K) n=5 animals per group. (L) or n=6 animals per group. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. ns, not significant. ** P<0.01. The error bars represent means ±SEMs. See Figure S5.

We found that when we exposed the labellum to a cool air stream (23° to 17°C), the S6 sensilla exhibited an increase in action potentials during the cooling phase (Figures 4B, 4D and 4G). The peak firing rate (PFR) was 14.7 ±1.2, which then declined (Figures 4B, 4D and 4G; 50% firing frequency decline, FFD50= 3.7 ±0.8 sec). The spikes that were induced by cooling appeared to be generated by bitter GRNs, as the amplitude of the spikes were similar to those produced in S6 sensilla by a bitter compound (caffeine), and were larger than mechanically-stimulated spikes (Figures 4G—4I). When we inactivated bitter GRNs by overexpressing Kir2.1 (UAS-kir2.1) under the control the Gr66a-Gal4, most S6 sensilla showed no increase in action potentials (Figure 4J, top trace), while some produced spikes (Figure 4J) that were the same amplitude as the spikes produced by MSNs (Figure 4I). However, of significance, the large spikes characteristic of bitter GRNs were eliminated, further indicating that the cooling-induced action potentials were generated in S6 sensilla by bitter GRNs.

I6 sensilla also responded to cooling and in response to the 23° to 17°C temperature ramp (Figures 4E, 4K and 4M; PFR= 8.2 ±1.2). The frequency of the cooling-induced action potentials declined rapidly (Figures 4E and 4K; FFD50= 5.2 ±0.5 sec). As with S6 sensilla, the action potentials stimulated by the cooling appeared to be derived from bitter GRNs since they were similar in amplitude to the action potentials produced by denatonium, but were larger than mechanically-induced action potentials (Figures 4K, S5A and S5B).

L3 sensilla also exhibited cooling-induced action potentials (Figures 4L and 4N; PFR=10.3 ±2.9; FFD50= 9.6 ±1.6 sec). In contrast to S6 and I6, the neurons responding to cooling appeared to be MSNs, since the amplitude of the spikes were similar to those produced by mechanical stimulation, but were smaller than sucrose-induced action potentials (Figures S5C and S5D).

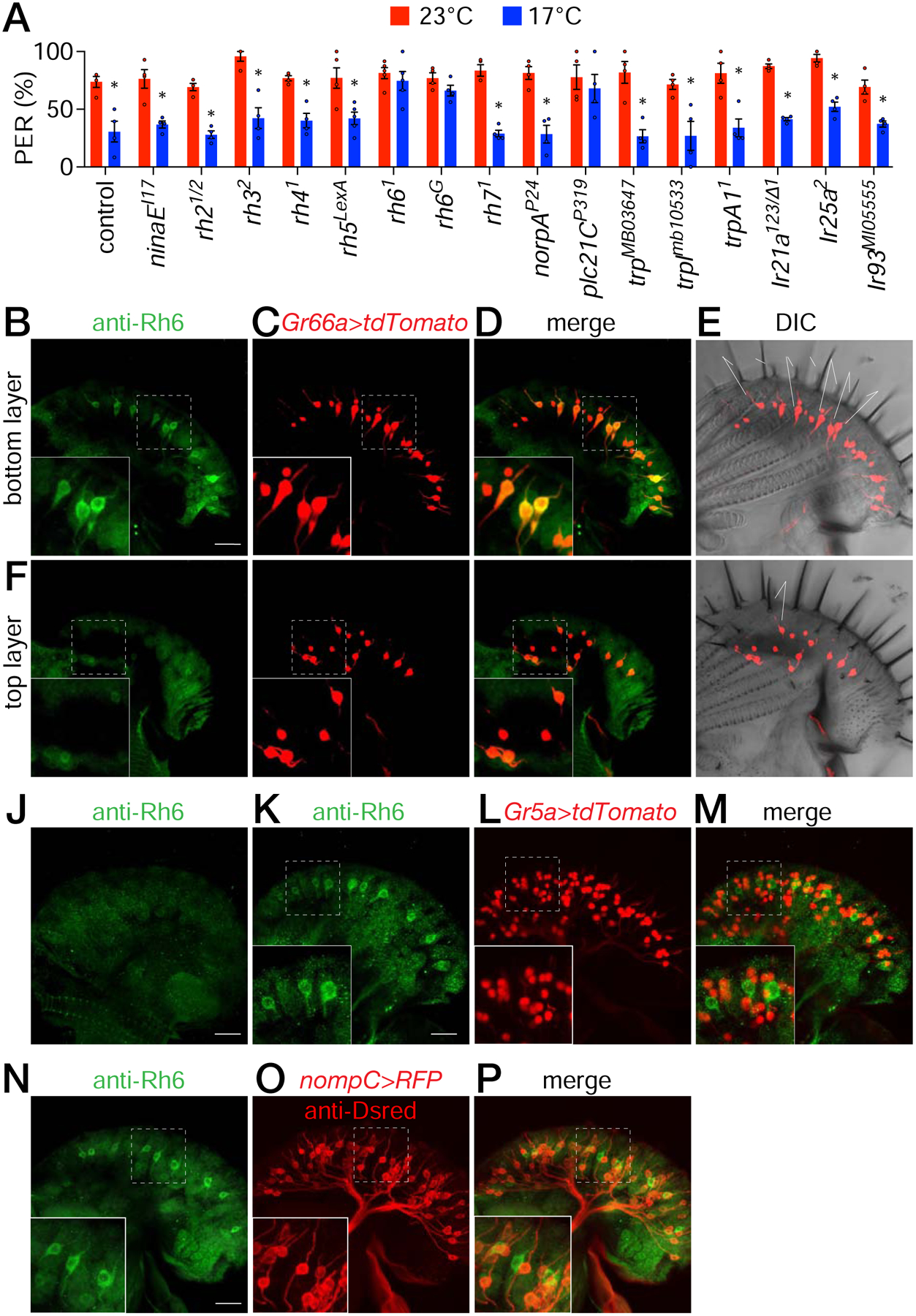

Requirement for Rh6 for aversion to cool sucrose

To identify a receptor that reduces the suppression of sucrose appeal when the food is cool, we considered rhodopsins. The Drosophila genome encodes seven opsins [15], and three (Rh1, Rh5 and Rh6) function in larvae in the discrimination of temperatures in the 18°—24°C range [16, 17], making them candidates for sensing temperature in the fly tongue. Therefore, we screened mutations disrupting each rhodopsin gene by performing PER assays using 0.5 M sucrose presented at either 23° or 17°C. Mutations affecting six of these rhodopsins did not reduce cool-induced sucrose attraction (Figures 5A, S6A and S6B). In contrast, the rh61 mutation virtually eliminated the lower attraction to 17° versus 23°C sucrose (Figure 5A, S6A and S6B). We repeated the PER assays with a second rh6 allele (rh6G) and found that these mutant flies exhibited a phenotype indistinguishable from rh61 (Figure 5A, S6A and S6B). Both rh6 mutants were also unable to discriminate a lower concentration of sucrose (0.1 M) at the two temperatures (Figures S6C—S6E).

Figure 5. Role for Rh6 for suppression of sucrose appeal, and expression of Rh6 in a subset of bitter GRNs.

(A) PER assays to screen for contributions of candidate signaling proteins to cool suppression of sugar attraction. Flies were presented with 0.5 M sucrose at either 23° or 17°C. Shown are the 3rd PER offerings. See Figures S6A and S6B for the results of the 1st and 2nd offerings. n=5 trials. Each trial includes ≥8 flies. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. *P≤0.05. Error bars represent means ±SEMs. See Figure S7A—S7D.

(B—I) Staining control labella with anti-Rh6, which labels bitter GRNs. UAS-tdTomato was expressed in bitter GRNs under the control of the Gr66a-Gal4.

(B—E) Z stacks focusing on S-type sensilla close to the inner surface of the labellum.

(B) Anti-Rh6 staining (green). Scale bar represents 20 μm.

(C) tdTomato fluorescence (red).

(D) Merge of B and C.

(E) tdTomato fluorescence superimposed on DIC image of the labellum. S-type sensilla are labelled. S6 is slightly longer than other S-type sensilla. The S-type nomenclature used is as described [56].

(F—I) Z stacks focusing on I-type sensilla close to the outer surface of the labellum.

(F) Anti-Rh6 (green).

(G) tdTomato fluorescence (red).

(H) Merge of F and G.

(I) tdTomato fluorescence superimposed on DIC image of the labellum. I-type sensilla are labelled.

(J) Staining rh6G mutant labellum with anti-Rh6.

(K—M) Staining a rh6+ labellum expressing UAS-tdTomato under the control of the Gr5a-Gal4, which labels sugar GRNs. Anti-Rh6 staining and tdTomato fluorescence are shown.

(K) Anti-Rh6 (green).

(L) tdTomato fluorescence (red).

(M) Merge of K and L.

(N—P) Co-staining a control labellum with anti-Rh6 and anti-DsRed, which labels MSNs (LexAop-rCD2::RFP/+ expressed under the control of the nompC-LexA/+).

(N) Anti-Rh6 (green).

(O) Anti-DsRed (red).

(P) Merge of N and O.

The main phototransduction cascade in fly photoreceptor cells couples rhodopsin activity to the phospholipase C (PLC) that is encoded by the norpA gene [18, 19]. However, norpAP24 mutant flies exhibited normal cool suppression of sucrose attraction (Figures 5A, S6A and S6B). In addition, to the primary signaling pathway that employs NORPA, an alternative phototransduction cascade in photoreceptor cells depends on a different PLC (PLC21C) for synchronization of the circadian clock [20]. We found that plc21CP319 flies showed a strong deficit in cool suppression of sugar appeal (Figures 5A, S6A and S6B). We also tested trp, trpl, and trpA1 mutant flies, as well as mutations disrupting three genes that function in cool sensing in adults and larvae (Ir21a, Ir25a and Ir93a) [21–23]. Similar to the control flies, each of these six latter mutants displayed significantly lower PERs at 17° versus 23°C sucrose (Figures 5A, S6A and S6B).

Rhodopsins have two components: a protein subunit called the opsin, and retinal. In the Drosophila visual system, retinal has two functions. It serves as the light sensitive subunit and as a molecular chaperone, which is required for rhodopsin to exit the endoplasmic reticulum [24]. To determine whether the retinal is necessary for cool suppression of sucrose attraction, we took advantage of the ninaD1 mutation, which eliminates a scavenger receptor required for uptake of carotenoids that serve as precursors for the retinal [25, 26]. We raised the ninaD1 flies on a carotenoid-free diet (CFD) for five generations to further deplete retinoids. This approach was effective, as the ninaD1 CFD flies were unresponsive to light, as determined by performing electroretinogram recordings (Figure S6F). The ninaD1 CFD flies did not show cool induced suppression of the sugar response (Figure S6G), consistent with a role for an opsin in sensing cool temperatures in labellum of flies.

To test whether light impacts on cool suppression of sucrose taste, we tested control flies under normal lights and under dim red darkroom safety lights, which is the functional equivalent to darkness, since dim red lights do not activate any fly rhodopsin, and flies show no positive phototaxis towards dim red light (Figure S6H). We found that the animals exhibited indistinguishable cool suppression under normal and dim red lights (Figure S6I), indicating that the requirement for Rh6 for cool taste sensing is light independent.

Rh6 functions in bitter GRNs

To determine whether Rh6 is expressed in the labellum we performed immunostaining. Anti-Rh6 labeled a subset of neurons in each labellum, but not in the rh6G mutant (Figures 5B and 5J). To identify the cell type expressing Rh6, we performed double-labeling experiments. We found that the anti-Rh6 positive neurons all co-labeled with bitter GRNs housed in S-type sensilla (Figures 5B—5E; Gr66a-Gal4 and UAS-tdTomato), but not I-type sensilla (Figures 5F—5I). Anti-Rh6 staining did not overlap with markers specific for sugar GRNs (Figures 5K—5M; Gr5a-Gal4 and UAS-tdTomato) or MSNs (Figures 5N—5P; nompC-lexA and lexAop-RFP). These data indicate that Rh6 is expressed in bitter GRNs.

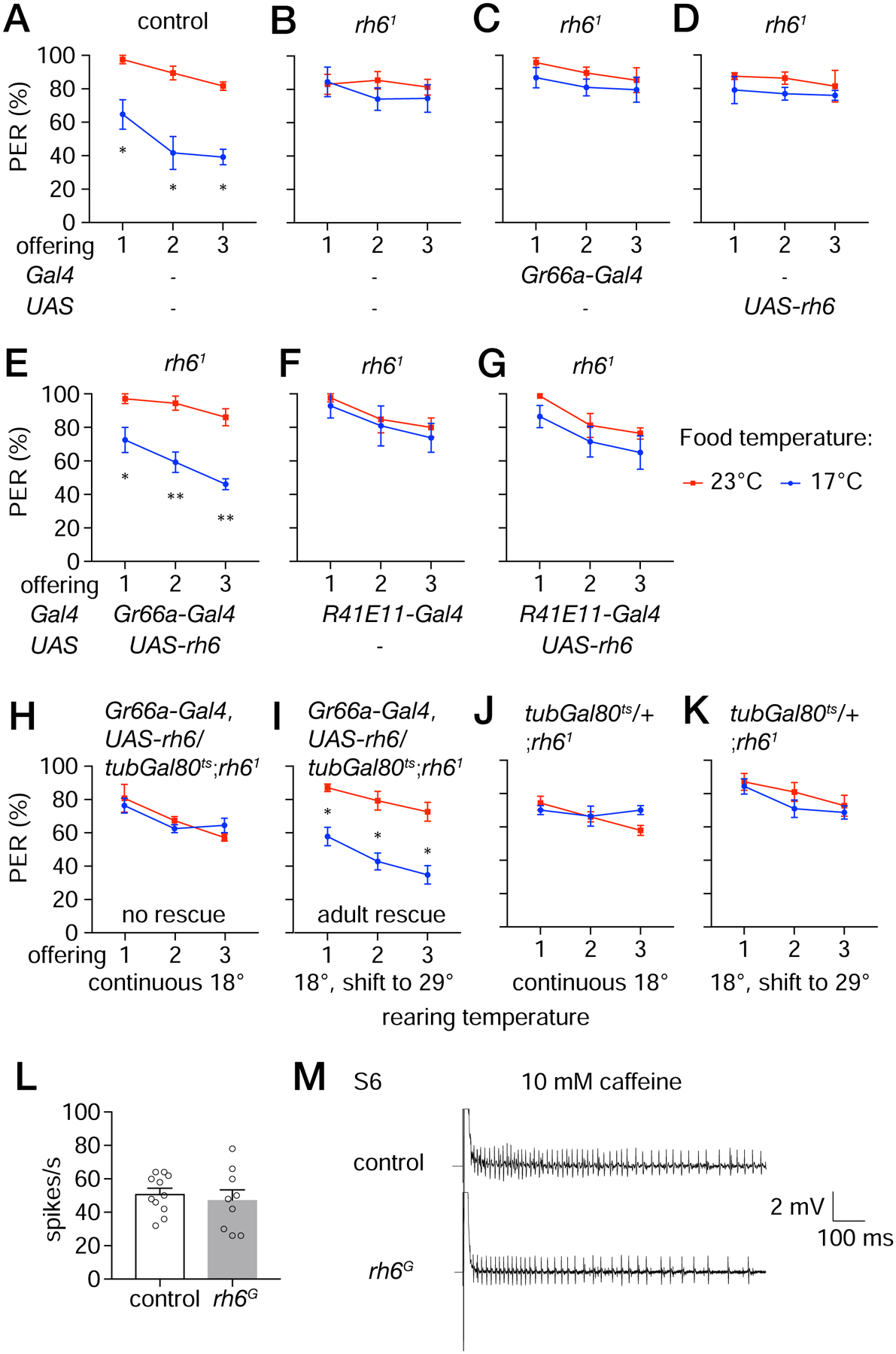

To test whether Rh6 functions in bitter GRNs, we expressed rh6 (UAS-rh6) in bitter neurons (Gr66a-Gal4) in rh61 mutant flies and performed PER assays. When we introduced only the Gr66a-Gal4 or UAS-rh6 in rh61, we did not rescue the rh61 mutant phenotype as the animals did not discriminate between 17° and 23°C sucrose (Figures 6C and 6D). However, when we co-expressed these two transgenes, we restored the decreased attraction to cool sucrose similar to the control flies (Figures 6A and 6E). In contrast, introduction of UAS-rh6 in MSNs (R41E11-Gal4) did not rescue the rh61 mutant phenotype (Figures 6F and 6G). These data indicate that Rh6 functions in bitter GRNs to facilitate cool thermosensation in the labellum.

Figure 6. rh6 functions in bitter GRNs for cool food avoidance.

(A—G) Testing for rescue of the rh61 phenotype by expressing rh6 in different classes of neurons in the labellum. PERs were monitored in control flies or rh61 flies expressing UAS-rh6 using the indicated Gal4 lines. The flies were presented three offerings of 0.5 M sucrose at either 23°C (red lines) or 17°C (blue lines). n=4 trials. Each trial includes ≥8 flies. Error bars represent means ±SEMs.

(A) Control flies.

(B) rh61 mutant flies.

(C) Bitter GRN Gal4 only (Gr66a-Gal4) in rh61 flies.

(D) UAS-rh6 only in rh61 flies.

(E) Expression of UAS-rh6 in bitter GRNs in rh61 flies under control of the Gr66a-Gal4.

(F) MSN Gal4 only (R41E11-Gal4) in rh61 flies.

(G) Expression of UAS-rh6 in MSNs in rh61 flies under control of the R41E11-Gal4.

(H—K) PER assays to determine whether rh6 is required in bitter GRNs only in the adult. Gal80ts is temperature sensitive suppressor of Gal4, and is active at 18°C but not 29°C. Flies were offered 0.5 M sucrose three times either at 23° or 17°C. Flies of the indicated genotypes were reared and maintained at 18°C throughout development and adulthood (H, J), or shifted to 29°C for 3 days following eclosion (I, K). n=4 trials. Each trial includes ≥8 flies. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. *P≤0.05. Error bars represent means ±SEMs.

(H, I) Gr66a-Gal4,UAS-rh6/tubGal80ts;rh61.

(J, K) tubGal80ts/+;rh61.

(L) Frequencies of action potentials (based on tip recordings) elicited by S6 sensilla in response to 10 mM caffeine. The spikes were counted between 50—550 ms after application of the recording electrode containing the caffeine. n=6 animals.

Non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Error bars represent means ±SEMs.

(M) Tip recordings traces using S6 sensilla in response to 10 mM caffeine. Time and mV scale bars are provided.

To address whether the defect exhibited by rh6 mutant flies reflects a role for Rh6 in mature GRNs or during GRN development, we limited the temporal expression of the rh6 rescue transgene to adult flies. To do so we took advantage of the Gal80ts, which is a temperature-sensitive inhibitor of Gal4 [27]. The Gal80ts is active at 18°C (and inhibits Gal4), but is inactive at 29°C, thereby permitting activity of Gal4 at this higher temperature. When we combined the Gal80ts with the Gr66a-Gal4 and UAS-rh6 in a rh61 background, and kept the flies at 18°C, the Gal4 was inactive, and the phenotype was indistinguishable from rh61 mutant flies (Figures 6B and 6H). However, when we shifted the temperature to 29°C following eclosion of adult flies, and performed the PER assays 3 days later, we restored the cool-induced suppression of sugar attraction (Figure 6I). In the absence of the transgenes that rescue the rh61 phenotype, the temperature shift to 29°C had no effect. The flies exhibited the same defect in cool-suppression of sugar taste as displayed by flies kept continuously at 18°C (Figures 6J and 6K). These data indicate that Rh6 is required in mature bitter GRNs for cool avoidance rather than for development of bitter GRNs. In further support of the conclusion that loss of rh6 did not cause a general defect in the bitter GRNs, we performed tip recordings and found that rh6G mutant flies produced a similar frequency of caffeine-induced action potentials as control animals (Figures 6L and 6M).

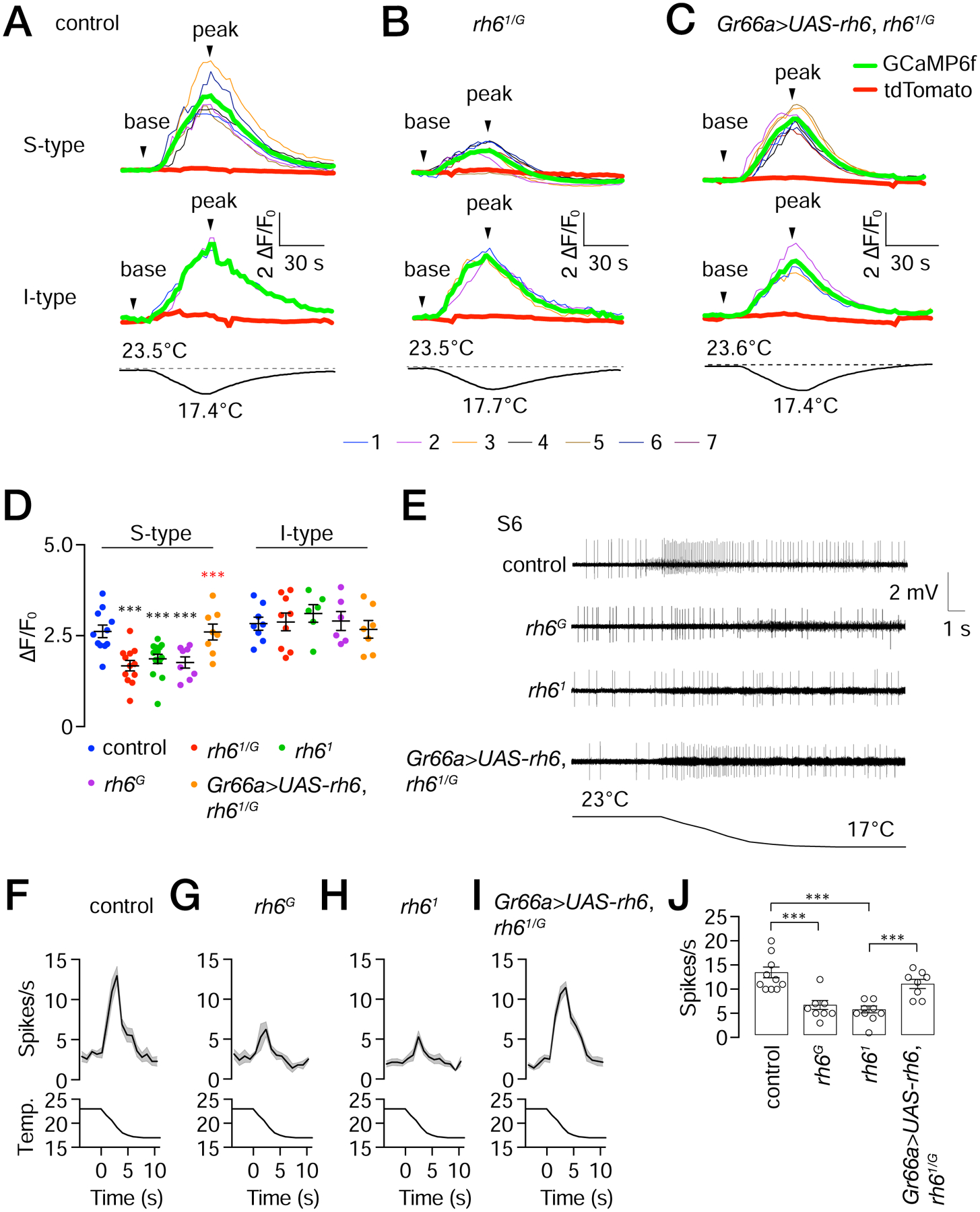

Rh6 is required for activation of bitter GRNs by cooling

To address whether loss of Rh6 impacts on activation of bitter GRNs by cool temperatures, we lowered the temperature of the labellum from 24 ±0.5°C (Δt= −6 ±0.5°C) and assayed cool-evoked Ca2+ dynamics (ΔF/F0) in the rh61/G mutant flies using GCaMP6f. We found that that the bitter GRNs in S-type sensilla showed a reduced Ca2+ rise in response to cooling (Figures 7A and 7B). We restored normal dynamics by expressing a wild-type rh6 transgene (UAS-rh6) in bitter GRNs using the Gr66a-Gal4 (Figure 7C). The cool-responses of bitter GRNs in I-type sensilla, which do not express Rh6, were unaffected by the rh61/G mutation (Figures 7A—7D).

Figure 7. Cool-induced GCaMP6f fluorescence and action potentials in rh6 mutants.

UAS-GCaMP6f and UAS-tdTomato were expressed in control, rh61/G, and in rh61/G mutant flies expressing UAS-rh6 using the Gr66a-Gal4 (Gr66a>UAS-rh6).

(A—C) GCaMP6f responses (ΔF/F0) to transient cooling in S- and I-type sensilla in control, rh61/G, and Gr66a>UAS-rh6 expressed in rh61/G flies as indicated. The upper traces depict GCaMP6f responses (ΔF/F0) to cool temperature stimuli. The thin colored traces represent each ROI. The bold red and green bold traces denote the average tdTomato and GCaMP6f fluorescence within the ROI. The lower traces show the cooling regime from 23.5—23.6° to 17.4—17.7°C.

(D) Maximum GCaMP6f fluorescence changes (ΔF/F0) due to ~6°C cooling exhibited by the control, indicated rh6 mutants and rh6 rescue flies (Gr66a>UAS-rh6) in S- and I-type sensilla. n=9—15 animals. Black asterisks indicate significant differences with the control. Red asterisks indicate significant difference with the rh61/G mutant. Error bars represent means ±SEMs. ***P≤0.001. Mann-Whitney test.

(E) Tip recording traces from S6 sensilla during cooling from the indicated flies. The temperature regime is indicated below. Time and mV scale bars are shown.

(F—I) Action potentials from S6 sensilla exposed to cooling. (F) control flies, n=10 animals. (G) rh6G. (H) rh61. (I) rh61/G, and Gr66a>UAS-rh6. n=8—10 animals/group.

(J) Statistical summary of peak spikes in response to cooling by the indicated flies. Error bars represent means ±SEMs. n = 8—10 animals/group. ***P≤0.001. Unpaired Student’s t-test.

To more directly test whether loss of rh6 impairs cooling-induced activation of the bitter GRNs in S6 sensilla we assayed action potentials. We found that in response to a 23°—17°C temperature ramp, the frequencies of action potentials were significantly reduced in the rh6G and rh61 mutant flies relative to the control (Figures 7E—7H and 7J). The small spikes that occasionally occurred, and which did not initiate coincident with the temperature ramp (e.g. Figure 7E, control), were most likely due to spontaneous activity of MSNs. We reversed the impairment in the transheterozygous rh61/G mutant by expressing the rh6+ transgene in bitter GRNs (Figures 7E, 7I and 7J), demonstrating that cooling-induced activation of bitter GRNs depends on Rh6.

Discussion

Cellular mechanism for cool suppression of sugar appeal

The demonstration that the palatability of sugar is diminished at cool temperatures establishes Drosophila as an animal model for studying the mechanisms through which temperature and the chemical composition of food are integrated. Cool temperatures are known to suppress olfaction in insects [28–31]. However, the effect of food temperature on feeding behavior is profound, as even a 2°C difference (21°C versus 19°C) is sufficient to diminish the urge to consume sugar.

A central question concerns the cellular mechanism through which slight coolness induces an attenuation in feeding behavior. To address this question, we used a genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor (GCaMP6f), and also assayed cooling-induced action potentials. We found that upon cooling, the sugar GRNs did not exhibit significant changes in Ca2+ levels or action potentials. These findings rule out that the negative impact of cool food is due to a strong temperature dependence of the ionotropic sucrose receptor, which may be comprised of at least GR64a and GR64f [13, 32–35], or is caused by effects on any other signaling protein in sugar GRNs. These include several trimeric G-proteins, phospholipase C, the IP3-receptor and an adenyl cyclase [36–41]. Our results that sugar GRNs do not respond directly to changes in temperature were surprising, as they contrast with a study in the mouse indicating that sweet responsive taste receptor cells elicit lower responses to cool temperature directly, due to diminished activity of TRPM5 at lower temperatures [42].

Rather than cool temperatures inhibiting sugar GRNs, bitter GRNs and MSNs are activated by cool temperatures, and are required for repressing sugar appeal. Using the in vivo Ca2+-sensor GCaMP6f, we found that modest cooling increases Ca2+ levels in bitter GRNs and MSNs. In addition, cooling increased firing of action potentials in bitter GRNs in S- and I-type sensilla, and MSNs in L-type sensilla. Thus, it is notable that while suppression of sugar appeal by cool temperatures is evolutionarily conserved in animals as disparate as flies and humans, the cellular mechanisms are very different.

Molecular mechanism for cool suppression of sugar appeal involves a rhodopsin

We found that in flies, the sensitivity of sugar taste to cool temperatures depends in part on a rhodopsin, Rh6 which is expressed and functions in a subset of bitter GRNs. In support of this conclusion, we observed the same phenotype in both rh6 mutant alleles examined, and we restored normal cool-suppression of feeding by introduction of a rh6 transgene in bitter GRNs. This role for Rh6 reflected a requirement for Rh6 in mature GRNs rather than during development since we rescued the rh6 mutant deficit by expressing the wild-type transgene exclusively in adults.

While Rh6 contributes to cool food detection, our data indicate that there are additional receptors that function in cool sensation in the labellum. Mutation of rh6 only reduces but does not eliminate the cool-activated responses in S-type sensilla, and has no impact on bitter GRNs in I-type sensilla or on MSNs. Moreover, mutation of any rhodopsin gene other than rh6 does not impact significantly on suppression of sugar appear by cooling. Thus, cool activation of bitter GRNs in I-type sensilla appears to be through a temperature sensor other than rhodopsin. Employment of a rhodopsin in S-type, which might couple to an amplification cascade that includes PLC21C, may endow these bitter GRNs greater sensitivity to mild cooling than bitter neurons in I-type sensilla. Consistent with this idea, we found that the peak activation to the same cool temperature ramp is higher in S6 than I6 sensilla.

Genetic and dietary elimination of retinal mimicked the rh6 mutant phenotype, further supporting the finding that a rhodopsin contributes to inhibition of the palatability of sucrose at lower temperatures. However, the role for Rh6 was light-independent, since the cool-induced inhibition of sugar appeal was indistinguishable in the light or under very dim red darkroom lights, which are not sensed by any fly rhodopsin. In fly photoreceptor cells, in addition to functioning in light detection, retinal serves as a molecular chaperone, promoting transport of rhodopsins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane [24]. Thus, the requirement for the retinal in bitter GRNs most likely reflects a similar role in facilitating exit of Rh6 from the endoplasmic reticulum.

We suggest that Rh6 may be functioning in S-type bitter GRNs as a direct thermosensor. Similarly, the three opsins that promote larval thermotaxis in the comfortable range may also be thermosensors [16, 17]. However, it has not been feasible to test this model using a heterologous expression system since these Drosophila opsins are retained in the endoplasmic in tissue culture cells. Nevertheless, given the high thermal stability of rhodopsins in photoreceptor cells [43], the cellular environments of the GRNs in the labellum, as well as the opsin-expressing thermosensory neurons in larvae may be tailored to lower the energy barrier that otherwise limits thermal activation of opsins. We are currently, investigating this proposal in an ongoing analysis. Following thermal activation, our data indicate that Rh6 is coupled to a signaling cascade that employs PLC21C, rather than the PLC (NORPA) that functions in the primary phototransduction cascade in fly photoreceptor cells [18, 19]. The identity of the channel that culminates this cascade remains to be identified. However, it does not appear to be TRP, TRPL or TRPA1, since mutant flies missing any of these channels retain cool-induced suppression of sugar feeding.

Possible mechanism through which cool-activation of bitter GRNs and MSNs inhibits sugar GRNs

Our findings that activation of bitter GRNs and MSNs attenuate the attractiveness of sucrose raises the question concerning the underlying circuit mechanisms. It has been shown previously that bitter GRNs activate a GABAergic interneuron [44]. These interneurons then suppress sugar GRNs, which express the GABAB receptor [44]. Thus, cool activation of bitter GRNs by cool temperatures appears to suppress sugar GRNs through this feedback circuit in the primary taste center in the brain—the subesophageal zone. Cool activation of bitter GRNs would also suppress feeding independent of effects on sugar GRNs, since stimulation of bitter GRNs reduces feeding through a label line mechanism. The axons of MSNs are in close proximity to the axons of sweet GRNs in the subesophageal zone. The MSNs produce GABA, which then inhibits sweet GRNs [3]. Consequently, cool activation of MSNs could also lead to suppression of sugar GRNs through a GABAergic mechanism.

Ethological significance of discrimination cooler and warmer foods

An intriguing question concerns the ethological significance of flies preferring slightly warmer over cooler sweet food. Flies are poikilothermic organisms, and because their body temperature equilibrates with the environment, a decrease in environmental temperature from only 25°C to 18°C lowers their activity, and the rate of development two-fold. Therefore, at cooler temperatures the animals do not consume as much food [45]. Indeed, if an organism does not adjust its food consumption in accordance with environmental temperature, there can be a fitness cost [46]. This proposal raises the possibility that other species of Drosophila that reside in environments that are cooler or warmer than Drosophila melanogaster have distinct thermal food preferences. An alternative but not mutually exclusive explanation is that decaying organic matter, which comprises a portion of a fly’s diet, is slightly warmer than the ambient temperature. The capacity to discriminate foods on the basis of temperature may contribute to a fly’s ability to discern between fresh and slightly warmer, decaying food sources.

Coding mechanism for differentiating thermal taste from bitter taste and mechanosensation

The various neurons that are activated by cool temperatures (bitter GRNs in S- and I-type sensilla, and the MSNs in L-type sensilla), respond to other stimuli such as bitter chemicals and food texture. This raises a question concerning the mechanism through which coolness is differentiated from other stimuli. If a fly is in a warm environment, or if the fly inserts its proboscis in warm decaying food, the bitter GRNs and MSNs are not stimulated by coolness. Alternatively, if a fly is in a cool environment, all of the cool-activated bitter GRNs and MSNs would be activated. Thus, if only a subset of these neurons is activated, it is unlikely that the fly is in a cool environment. We found that inactivation of just bitter GRNs, just MSNs, or loss of rh6 from the bitter GRNs in S-type sensilla are all sufficient to eliminate cool-induced suppression of sucrose appeal. We suggest that the requirement for stimulation of all cool-activated neurons in the labellum to respond to coolness might provide a coding mechanism for the animal to differentiate coolness, from other activation modes, such as bitter or mechanical stimulation, that would stimulate just a subset of these neurons.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

The lead contact is Craig Montell.

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact without restriction. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Fly stocks

The control flies were w1118. Gr66a-Gal4 (chromosome 2 insertion, from H. Amrein) [47], Gr66a-Gal4 (chromosome 3 insertion) (Bloomington Stock 57670), Gr64f-Gal4 (Bloomington Stock 57669), UAS-TNT-E [14], R41E1-Gal4 (Bloomington Stock 50131), ppk28-Gal4 [48], TMC-Gal4 [2], UAS-tdTomato (Bloomington Stock 36327, 36328), UAS-rh6 (generated by W. Liu and C. Montell, unpublished) [49],UAS-GCaMP6f (Bloomington Stock 42747), nompC-lexA [50], LexAop-rCD2::RFP (Bloomington Stock 67093), ninaEI17 (Bloomington Stock 5701), rh21 (generated in C. Montell laboratory), rh32 (described below), rh41 [49], rh5LexA (described below), rh61 (Drosophila Genomics and Genetic Resources, Kyoto Stock 109600) rh6G (Bloomington Stock 66672), rh71 [51], Canton S, rh22, (null mutation generated by A. Ganguly and C. Montell, which will be described separately), ninaD1 (Bloomington Stock 42244), trpMB03672 [52], trplMB10533 (Bloomington Stock 29134), trpA11(Bloomington Stock 26504) [53], Ir21a123, Ir21aΔ1 [23], Ir25a2 (Bloomington Stock 41737) [54], Ir93aMI05555 (Bloomington Stock 42090) and tub-Gal80ts (Bloomington Stock 7018). All the mutants were backcrossed into the control background (w1118) for 5 generations.

Fly husbandry

Flies were reared at 25°C on normal cornmeal/molasses food under 12 hr light/12 hr dark cycles. All the flies used for experiments were 3—5 days old and were transferred to fresh vials in a density of 30~50 flies per vial after eclosion.

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of rhodopsin mutant flies

To create the null rh32 mutant, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 to delete −3 to +555, which removes the region coding for the N-terminus and the transmembrane segment 1 (Figures S7A and S7B). The guide RNAs to generate the deletion are: guide RNA1: TTGGCCCGCAGACCGGAGCA, and guide RNA2: GCAGGCAACCACCCATGGAG. The primers for genotyping are: P1, TACTGCAACCCAAAATGGTCA, and P2, TCCACGTTCATCTTCTTGGCC.

To generate the rh5LexA null mutant, we replaced (+51—+236) with the LexA and mini white (w+) genes (Figures S7C and S7D). The deletion removed amino acids 17—67 and the first transmembrane domain. The guide RNAs for creating the rh5LexA allele using CRISPER-Cas9 are: guide RNA1: GCCTATGTGAACGATAGCTT, and guide RNA2: GGATTAATGTGGGGATTAAT. The PCR primers to generate the 5’ and 3’ homology arms are: forward primer for 5’ arm, ATTAATCCCCACATTAATCCAGACGA; reverse primer for 5’ arm, GCAACAAGTCGGGCACACAATAAGAG; forward primer for 3’ arm, GCTGCTTAAGTCATCGACAGTCGAGC, and reverse primer for 3’ arm, AAGCTATCGTTCACATAGGCCTGT. The PCR primers for genotyping are: P1, GGCACCTATCTACTATCACGCCG; P2, ACGTCCGTCTATTGGATTGG; P3, GAACCTGGTACATCAAATACCCTTGG; P4, ATTCGCAACTGGGTCTCAAG; P5, TCCATGTCCCATTGGAAAGAC; and P6, TATTTTCTGGCCGCCTAATG.

Proboscis extension response (PER) assays

We performed the PER assays in the afternoon (ZT6—ZT10) at 23°C. We used males starved for 2 hours for the assays, unless indicated otherwise. The control flies were w1118. The surgery to remove antennae was performed on 2—3 day-old flies, and they were allowed to recover for 2 days prior to performing the PER assays. The cool (17°—21°C) and warm probes were custom build by Christian Landry (ProDev Engineering, Missouri City, TX., Figure S1A) [55].

PER assays were conducted by stimulating the labellum, except for the indicated experiments in Figure 1D—1F, which were performed by stimulating tarsi. The animals were stimulated for ~0.2—0.4 sec on the labellum or tarsi with 0.5 μL liquid placed at the tip of the probe. This rapid application of the liquid is illustrated in the images of consecutive frames extracted from video S2 (Figure S1D). The frame rate is 0.2 sec/frame, and the brief contact spanned two frames. For contacting a fly on their tarsi, the animals were anesthetized on ice for ~5 min and immobilized with their dorsal side down on myristic acid (M3128, Sigma-Aldrich) strips. We allowed the flies to recover in a humidified chamber for 2 hours before testing. The liquid (0.5 μL) was applied to the tarsi without contacting the labellum. For contacting the labellum, unless indicated otherwise, we starved the flies for 2 hours by transferring the animals from fresh food to vials containing a moist Kimwipe. We then removed the flies with negative aspiration, and trapped them in the ends of 200 μL pipette tips by expelling them with positive aspiration. Before performing PER assays, we water saturated the flies by offering them water at the end of probe until they no longer extended their proboscis and consumed water. Over 90% of the flies were hydrated, as indicated by ≤3 sec of water consumption when offered at the end of a probe. If the flies drank water for >3 sec, they were discarded either because they were not water hydrated or because the excessive drinking might indicate physical damaged to the labellum.

We used three values to score the PER assay. A score of 1.0 indicates a fly that extended its proboscis and ingested for ≥1 sec after being presented with the probe. If the fly extended its proboscis and consumed food for <1.0 second, then the score was 0.5. The score was 0 if the fly failed to extend its proboscis. We performed 3 consecutive PER assays (offerings) per fly, interspersed by 1 min intervals. During each offering, the flies were allowed to feed for only 2 seconds. To eliminate unresponsive animals, we offered 1 M sucrose solution 3—5 mins after completing the test. Flies that exhibited no PER were not included in the data set. Each trial, which is considered as an n=1 included ≥ 8 flies. The PER index per trial was calculated as: (sum of the score)/(number of flies tested) × 100%.

Using the Gal80ts for rescue of the rh61 phenotype during the adult stage only

To test whether Rh6 was required for cooling-induced sucrose attraction in the adult, we tested for rescue of the PER impairment in the rh61 mutant by allowing the wild-type rh6 rescue transgene to be functional only in the adult. To do so we used the temperature sensitive Gal4 repressor—the Gal80ts [27], which is active at 18°C and inactive at 29°C. We combined the tub-Gal80ts transgene with the Gr66a-Gal4 and the UAS-rh6 in a rh61 background. The flies were raised at 18°C and shifted to 29°C (or keep at 18°C as a control) for 3 days following eclosion. The flies were starved for 2 hours on a moist Kimwipe at the same temperature before testing. PER assays was performed at an environmental temperature of 23°C.

Phototaxis assays

To determine whether the flies were unresponsive to dim red lights (~644—667 lux, Deep Blue Solarflare Micro LED; 630 nM) we performed phototaxis assays using a Y tube. 100 ±10 flies (3—5 days old) were transferred to a “dark” fly vial (9.5 cm height and 2.3 cm diameter vial wrapped in aluminum foil) for 30 minutes to allow the flies to adapt to darkness. We then replacing the cotton ball at one end the black vial with a Y shaped plastic tube (each cylinder arm has an inner diameter of 0.55 cm). One side of the Y tube arm was wrapped with foil and was connected to another dark vial, and the other side to a transparent vial. We then arranged the apparatus so that it was vertical, gently tapped down the apparatus so that all flies were in the bottom black vial, and allowed the flies to make a choice for 5 minutes. We conducted the experiments so that the transparent side was exposed to either white light (~676—678 lux) or dim red lights. Typically, ~15—30 flies select one of the top two vials. Number of flies in two vials were tabulated. P.I. = (flies in upper light tube) - (flies in dark tube)/total flies in the upper light and dark tubes.

Immunostaining

All immunostaining was performed using whole mount preparations of labella, and the images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope. In brief, dissected labella (each labium is cut off by fine scissors) were fixed for 2 hr in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1x PBS. The samples were washed 3 times in washing buffer (0.3% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS) following by 1 h blocking in washing buffer contain 5% normal goat serum, and then incubated with primary antibodies for 2 days at 4°C in 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% normal goat serum in 1x PBS. After washing 3 times for 1 hour each, the tissues were incubated overnight at 4°C with secondary antibodies diluted in 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% normal goat serum in 1x PBS. After 4 washes (≥1 hr each time), the labella were mounted on glass slides with VECTASHIELD anti-fade mounting media (Vector Labs, catalog. H-1200). Primary antibodies: anti-Rh6 (mouse, 1:10, from Stephen Britt), and anti-dsRed (rabbit,1:200, Takara Bio #632496). Secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-11001), and Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-11036).

GCaMP6f imaging

To assay changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels in GRNs and MSNs we expressed UAS-GCaMP6f under the control of the indicated Gal4 drivers. As a control to normalize the data, we also expressed UAS-tdTomato in the same neurons. To perform the analyses, fly heads were cut with fine scissors, the cutting area was sealed silicone lubricant (Dow Corning, DC 976 High Vacuum Grease) and the labellum was extended and immobilized with silicone lubricant in a chamber made by cutting the short end of a 200 μL pipet tip sealed on a glass slide with nail polish. The labellum was exposed to 1X PBS buffer (Figure S8A). We performed the imaging using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope under a 20x water immersion objective. The chamber was placed directly on a cover slip on top of the cold side of a Peltier plate (07111–5L30–25CJ Thermoelectric/Peltier Module) powered by a Velleman PS1503SBU DC Lab Power Supply (Figure S8B). Using thermal conductive double sided tape, we attached an aluminum block (length: 65 mm, width: 76 mm, height: 4.2 mm; Figure S8B) directly below the Peltier devise as a heat sink. The temperature of the chamber was monitored with a temperature probe (IT-18, type T thermocouple Probes, Physitemp), and the data were recorded (1 sec per data point) using temperature logger software (NI USB-TC01, National Instrument). To apply sucrose stimuli, we dissolved 1.3 M sucrose in PBS, and then added 28 μL of the 1.3 M sucrose to 45 μL buffer in the chamber. It took 3—4 frames (1.97 sec/frame) for the sucrose to mix thoroughly, as reflected by a change in the refraction index during mixing of the solution. This is illustrated by the transient change in focus of the tdTomato during the mixing (Figures 2D, S3B and S3D). To apply sugar stimuli to the same sample at two different temperatures, we washed the chamber several times with distilled H2O to remove the sugar, and allowed the GCaMP6f fluorescence to return to the baseline level. The pinhole on the microscope was set to the maximum opening (26.6 μm) and images were recorded at a rate of one frame every 1.97 sec. The cells that we selected for imaging are those that remained in focus throughout the entire imaging process, using the tdTomato as the reference (Figure S2).

To quantitatively analyze the data, images were batch processed with imageJ to determine the GCaMP6f fluorescence intensity of ROI, which were normalized with tdTomato to minimize deviations due to tissue movement. For some of the videos with movements in the X or Y directions, we stabilized the motion by tracking the cells using Adobe Effect software. To set the baseline (F0), we used average intensities of the five frames prior to application of the stimuli. Changes in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F0) was used to assess the Ca2+ responses. We wrote a custom MATLAB script to view dual videos of the same labellum to reveal GCaMP6f dynamics and tdTomato fluorescence in parallel. The script also allows us to superimpose the changes in temperature and ΔF/F0, while the videos are running. Because the temperature of the preparation was recorded at different intervals than the fluorescence data, we linearly interpolated the temperature recordings to find appropriate values to display for each frame of the videos.

Tip recordings to assay responses to caffeine

To measure tastant-induced action potentials on labellar hairs, flies were immobilized by inserting a glass capillary filled with Ringer’s solution into the abdomen so that it extended all the way to the head. This electrode was used as the reference electrode. S6 sensilla were stimulated with a recording electrode (World Precision Instruments, 1B150F-3) with 10—20 μm openings (Sutter Instrument, P-97 puller) containing 10 mM caffeine and 1 mM KCl as the electrolyte. The signals were collected and amplified ten-fold using a signal connection interface box (Syntech) and a 100—3000 Hz band-pass filter. We recorded the action potentials at a 10.7 kHz sampling rate, and analyzed the data using Autospike 3.1 software (Syntech).

Assaying cooling- and mechanically-induced action potentials

To measure cooling- and mechanical-induced action potentials in neurons in labellar sensilla, we adapted the tip recording setup for assaying action potentials in response to tastants. We removed fly heads and immobilized them on a small amount of silicone lubricant (Dow Corning, DC 976 High Vacuum Grease) on a microscope slide with the proboscis extended. The heads in this preparation remain responsive to cool temperature ramps for ~20 minutes, based on experiments with GCaMP6f. The reference electrode was a glass capillary filled with Ringer’s solution, which we inserted into electrode cream (SignaCreme) on the fly eye. The recording electrode (10—20 μm tip diameter) contained 30 mM tricholine citrate. The signals were collected and amplified ten-fold using a signal connection interface box (Syntech) and a 100—3000 Hz band-pass filter. We recorded the action potentials at a 10.7 kHz sampling rate, and analyzed the data using Autospike 3.1 software (Syntech).

To apply a 23° to 17°C air stream (10 mL/sec), expirated using a Syntech CS-55 Stimulus Controller), we used an In-line Heater/Cooler (SC-20, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA), which was under control of a temperature controller (CL-100, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA). The air stream was passed through a water-containing flask to reduce dryness due to the air stream. The In-line Heater/Cooler was mounted on a micromanipulator and placed 2 mm from the specimen. The temperature of the preparation was monitored with a temperature probe (IT-23, Type T Thermocouple Probes, Physitemp) placed 1 mm behind the specimen, and the temperature data were recorded (1 data point/sec) using temperature logger software (NI USB-TC01, National Instruments). Mechanical stimulation of sensilla was achieved by directly deflecting the sensilla 20 μm with a tip of a recording pipet, using a motorized micromaniplator (Scientifica PatchStar).

Electroretinogram recordings

Two glass electrodes filled with Ringer’s solution were inserted into small drops of electrode cream (SignaCreme) placed on the surfaces of the compound eye and the thorax. Flies were exposed to 5 sec of orange light (Klinger Educational Products, 580 nm filter). Light-induced signals were amplified using an IE-210 amplifier (Warner Instruments) and the data were acquired with a Powerlab 4/30 device and LabChart 6 software (AD Instruments).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptions, results and sample sizes of each test are provided in the figure legends. All replicates were biological replicates using different flies. Data for all quantitative experiments were collected on at least three different days. For the PER behavioral experiments each “n” represents a single test performed with ≥8 animals. Based on our experience and common practices in this field, we used a sample size of n=4—6 for each genotype or treatment of a given group. For quantification of the Ca2+ imaging, each data point represents the responses of the calculated average (bold green line in each plot) of all the indicated neurons (ROI) in the field exposed to the indicated stimulus. Each “n” represents an analysis of a single, independent fly (n=5—14). Each “n” for the tip recording experiments and ERGs represents an analysis of a single, independent fly (n=5–10). All error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM).

Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software. For parametric tests, we used the unpaired Student’s t-test with the Tukey post-hoc test. For non-parametric tests, we used the Mann-Whitney test with Wilcoxon rank sum test. We used nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests to compare two groups of behavioral data (e.g. 23° vs 17°C of the same genotype). We used the unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test to compare two groups of Ca2+ imaging or electrophysiological data. For comparisons between different groups (Figures 3B—3G; Figures S4A—S4L), we used the two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-hoc test. We set the significance level, α=0.05 and power, 1-β=0.9. Asterisks indicate statistical significance, where * indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p<0.01, and *** indicates p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Video S1. PER assay showing a fly accepting 0.5 M sucrose at 23°C. Related to Figure 1.

Video S2. PER assay of a fly rejecting 0.5 M sucrose solution at 17°C. Related to Figure 1.

Video S3. Sugar GRNs do not respond to cooling. Related to Figure 2. Shown are the dynamic cooling-induced changes in GCaMP6f fluorescence (ΔF/Fo) in sugar GRNs from a Gr64f-Gal4/UAS- GCaMP6f,UAS-tdTomato labellum. A time scale and temperature ramp are shown.

Video S4. GCaMP6f responses in sugar GRNs stimulated with 0.5 M sucrose at either 23° or 17°C. Related to Figure 2. Shown are the GCaMP6f (ΔF/Fo) changes exhibited by sugar GRNs from Gr64f-Gal4/UAS-GCaMP6f,UAS-tdTomato labella in response to sucrose presented at 23° or 17°C. Time scales and temperatures of the sugar are shown.

(A) Sucrose stimulation at 23°C.

(B) Sucrose stimulation at 17°C.

Video S5. GCaMP6f responses of sugar GRNs by 0.5 M sucrose are not suppressed by cooling. Related to Figure 2. Shown are the GCaMP6f (ΔF/Fo) changes exhibited by sugar GRNs from a Gr64f-Gal4/UAS-GCaMP6f,UAS-tdTomato labellum upon activation by sucrose and then subjected to cooling. A time scale and temperature ramp are shown.

Video S6. GCaMP6f responses of bitter GRNs to cooling. Related to Figure 2. Bitter GRNs from a Gr66a-Gal4/UAS- GCaMP6f,UAS-tdTomato labellum were subjected to cooling. Shown are the GCaMP6f (ΔF/Fo) changes. A time scale and temperature ramp are shown.

Video S7. GCaMP6f responses of MSNs by cooling. Related to Figure 2. MSNs from a R41E11-Gal4/UAS- GCaMP6f,UAS-tdTomato labellum were subjected to cooling. Shown are the GCaMP6f (ΔF/Fo) changes. A time scale and temperature ramp are shown.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-Rh6 (mouse) | Stephen Britt | |

| anti-DsRed antibody (rabbit) | Clontech Laboratories, Inc. | Cat # 632496, RRID: AB_10013483 |

| Goat anti-mouse, Alexa488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # A11001, RRID: AB_2534069 |

| Goat anti-rabbit, Alexa568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat # A11036, RRID: AB_10563566 |

| Chemicals | ||

| Sucrose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # S0389 |

| Aristolochic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # A9451 |

| Piperonyl acetate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # W291218 |

| Dry yeast | Genesee Scientific | Cat # 62–103 |

| D-(+)-glucose | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # G8270 |

| Rice powder | United Foodstuff Company | N/A |

| Agar | BD Diagnostics | Cat # 214010 |

| Cholesterol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # C8667 |

| Methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # H5501 |

| Propionic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat # 81910 |

| Myristic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | M3128 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma | Cat # X100 |

| VECTASHIELD anti-fade mounting media | Vector Labs | Cat # H-1200 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Drosophila: w1118 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL5905 |

| Drosophila: Gr66a-Gal4 (chromosome 2 insertion) | [47] | NA |

| Drosophila: Gr66a-Gal4 (chromosome 3 insertion) | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL57670 |

| Drosophila: Gr64f-Gal4 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL57669 |

| Drosophila: UAS-TNT-E | [14] | NA |

| Drosophila: R41E1-Gal4 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL50131 |

| Drosophila: ppk28-Gal4 | [48] | NA |

| Drosophila: TMC-Gal4 | [2] | Cat # BL62176 |

| Drosophila: UAS-tdTomato | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL36327 |

| Drosophila: UAS-tdTomato | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL36328 |

| Drosophila: UAS-rh6 | Laboratory of Craig Montell | NA |

| Drosophila: UAS-GCaMP6f | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL42747 |

| Drosophila: nompC-lexA | [50] | NA |

| Drosophila: LexAop-rCD2::RFP, UAS-mCD8::GFP | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL67093 |

| Drosophila: ninaEI17 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL5701 |

| Drosophila: ninaD1 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL42244 |

| Drosophila: rh21 | Laboratory of Craig Montell | N/A |

| Drosophila: rh32 | This paper | N/A |

| Drosophila: rh41 | [49] | N/A |

| Drosophila: Gr5a-GAL4 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL57592 |

| Drosophila: rh5LexA | This paper | N/A |

| Drosophila: rh61 | Drosophila Genomics and Genetic Resources (Kyoto Stock Center) | Cat # 109600 |

| Drosophila: rh6G | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL66672 |

| Drosophila: rh71 | [51] | N/A |

| Drosophila: rh22 | Laboratory of Craig Montell | N/A |

| Drosophila: trpMB03672 | [52] | N/A |

| Drosophila: trplMB10533 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL29134 |

| Drosophila: trpA11 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL26504 |

| Drosophila: Ir21a123 | [23] | N/A |

| Drosophila: Ir21aΔ1 | [23] | N/A |

| Drosophila: Ir25a2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL41737 |

| Drosophila: Ir93aMI05555 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL42090 |

| Drosophila: tub-Gal80ts | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | Cat # BL 7018 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| rh32 genotyping PCR primer sequences P1: TACTGCAACCCAAAATGGTCA | This paper | N/A |

| rh32 genotyping PCR primer sequences P2: TCCACGTTCATCTTCTTGGCC | This paper | N/A |

| rh5LexA genotyping PCR primer sequences P1: GGCACCTATCTACTATCACGCCG | This paper | N/A |

| rh5LexA genotyping PCR primer sequences P2: ACGTCCGTCTATTGGATTGG | This paper | N/A |

| rh5LexA genotyping PCR primer sequences P3: GAACCTGGTACATCAAATACCCTTGG | This paper | N/A |

| rh5LexA genotyping PCR primer sequences P4: ATTCGCAACTGGGTCTCAAG | This paper | N/A |

| rh5LexA genotyping PCR primer sequences P5: TCCATGTCCCATTGGAAAGAC | This paper | N/A |

| rh5LexA genotyping PCR primer sequences P6: TATTTTCTGGCCGCCTAATG | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pBPLexA::p65Uw | Donor vector | Addgene Plasmid # 26231 |

| pU6-BbsI-chiRNA | gRNA vector | Addgene Plasmid # 45946 |

| Other | ||

| Glass capillaries | World Precision Instruments | Cat # 1B150F-3 |

Highlights.

Flies find sweet foods less appealing if they are cool

Rejection of cool food requires bitter taste neurons and mechanosensory neurons

Bitter taste neurons and mechanosensory neurons in the fly tongue are cool activated

A rhodopsin is required in a subset of bitter taste neurons for rejecting cool food

Acknowledgments

We thank Dhananjay Thakur for help with setting up the temperature-controlled Peltier system (Figure S7F). This work was supported by a grant to CM from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC016278).

Footnotes