Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are used as anti-inflammatory controller therapy given either alone or in a combination with long-acting bronchodilators for persistent asthma. The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has inevitably focused attention on whether ICS could predispose to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, especially in older, male, obese, smokers with comorbidities including chronic lung diseases who are susceptible to severe COVID-19 infection and worse outcomes. In the later stages of COVID-19 infection, there is an acute inflammatory cytokine cascade including interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. This in turn results in a hyperinflammatory and coagulopathy state with acute respiratory distress syndrome and an attendant high morality rate. A United Kingdom (UK) database of 17 million adult patients reported that the presence of asthma without recent oral corticosteroid use was associated with an 11% increased risk of hospital death with COVID-19, and a 25% increased risk in those with recent oral corticosteroid use. The UK RECOVERY trial in COVID-19 showed that treatment with dexamethasone 6 mg daily in 2014 patients compared to usual care in 4321 patients resulted in a 20% and 35% reduction in deaths among those who required oxygen alone or invasive ventilation respectively. Although ICS exhibit dose-related systemic absorption from the lungs, the degree of attendant systemic glucocorticoid activity in patients with asthma is relatively low compared with that of oral corticosteroids. Whether or not ICS might confer a different risk-benefit profile in COVID-19 is presently unknown. Here, we discuss the positive and negative effects of using ICS in relation to COVID-19 (Fig 1 ).

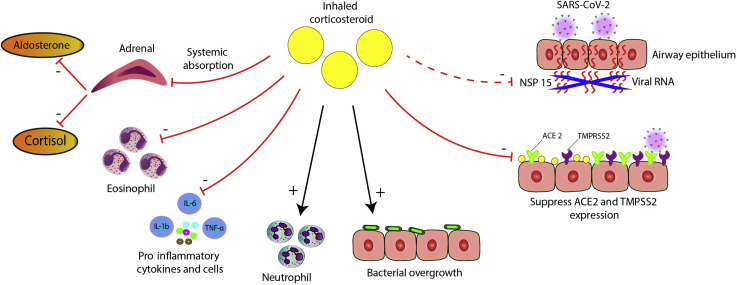

Figure 1.

Depicts putative positive and negative effects of ICS in COVID-19 infection on (A) viral replication of SARS-CoV-2, including specific effects of mometasone furoate and ciclesonide on nonstructural protein 15, (B) reduced expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2, (C) suppression of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, (D) promotion of secondary bacterial infection, (E) effects on neutrophils and eosinophils, and (F) suppression of adrenal secretion of cortisol and aldosterone. ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; IL-6, interleukin 6; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine protease 2.

Concerns around the use of ICS in patients with asthma and COVID-19 arise from the potential immunosuppressive effects in the lungs, especially in the presence of an impaired host defense. Here, the premise is that corticosteroids may promote viral replication, delayed viral clearance, and may also predispose to secondary bacterial infection. A Canadian cohort study of asthma patients found that current exposure to ICS was accompanied by a 45% relative increase in risk of bacterial pneumonia. In contrast, a study of H1N1 influenza A infection among 1520 hospitalized patients in United Kingdom found that those with asthma were 49% less likely to require intensive care support or were less likely to die than those without asthma, which was attributed to ICS use.

This suggests the possibility of a class effect of ICS by providing protection against viral insults in patients with asthma, which might be because of downstream cytokine suppression. In favor of this hypothesis, in vitro suppressive effects were seen with budesonide on the production of cytokines including IL-6 and IL-8, using primary cultures of human nasal and tracheal epithelial cells, whereas another in vitro study found systemic suppression of IL-6 by budesonide.1 , 2 This could be particularly relevant because raised levels of IL-6 are strongly related to worse outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia with evidence of hyperinflammation. In addition, it has been found that in sputum cells from 330 asthma patients, the use of ICS was associated with reduced gene expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and transmembrane serine protease 2, both of which are pivotal membrane bound receptors involved in the host cell entry of SARS-CoV-2.3 Moreover, in patients with type 2 asthma, exposure to exogenous IL-13 in ex vivo primary airway epithelial cells decreases angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and increases transmembrane serine protease 2 expression.4 Whether the altered cell receptor expression translates into reduced viral load with ICS therapy is unknown.

In addition, there are preliminary data suggesting a more specific salutary effect of ICS with COVID-19. In vitro experiments have found that ciclesonide and mometasone but not fluticasone; budesonide or beclomethasone suppress the replication of SARS-CoV-2 to the same degree as lopinavir.5 The inhibitory action of ciclesonide on the replication of SARS-CoV-2 was mediated through nonstructural protein 15. There have been case reports of COVID-19 pneumonia successfully treated with inhaled ciclesonide, but no data from the ongoing randomized controlled trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers, NCT04416399, NCT04381364, NCT04377711) have been available. With respect to COVID-19 pneumonia, inhaled ciclesonide achieves high alveolar deposition and prolonged lung retention owing to the formation of intracellular fatty acid conjugates in addition to producing minimal systemic adverse effects at higher doses.

Studies in health informatics may help to elucidate whether ICS alleviate or worsen COVID-19 outcomes in patients with asthma, particularly by looking at dose-response effects. One UK database study among 817,973 people with asthma observed a nonsignificant 10% increase in COVID related mortality associated with use low or medium dose ICS and a significant 52% increase with high dose ICS, which was plausibly explained by confounding due to disease severity. Randomized controlled trials may also be warranted in patients who do not have asthma to confirm whether secondary prevention with ICS including ciclesonide or mometasone can prevent progression of early COVID-19 infection in susceptible older patients with comorbidities. Meanwhile, for patients with asthma, the current guidance is to continue taking their ICS containing controller therapy because it may confer optimal protection against viral infections including SARS-CoV-2 and may also prevent eosinophilic related exacerbations.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr Lipworth reports receiving grants and personal fees from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, and Teva; reports receiving personal fees from Cipla, Glenmark, Lupin, Vectura, Dr Reddy’s, and Novartis; reports receiving grants, personal fees, and other support from Chiesi; reports receiving personal fees from Circassia and Thorasys, outside of the submitted work; and Dr Lipworth’s son is an employee of AstraZeneca. Dr Chan has no conflicts of interest to report. Dr Kuo reports receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca and Chiesi, relevant to the submitted work, and from Circassia, outside of the submitted work.

Funding: The authors have no funding sources to report.

References

- 1.Yamaya M., Nishimura H., Deng X. Inhibitory effects of glycopyrronium, formoterol, and budesonide on coronavirus HCoV-229E replication and cytokine production by primary cultures of human nasal and tracheal epithelial cells. Respir Investig. 2020;58(3):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suda K., Tsuruta M., Eom J. Acute lung injury induces cardiovascular dysfunction: effects of IL-6 and budesonide/formoterol. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(3):510–516. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0169OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters M.C., Sajuthi S., Deford P. COVID-19 related genes in sputum cells in asthma: relationship to demographic features and corticosteroids [e-pub ahead of print]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202003-0821OC accessed June 27, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kimura H., Francisco D., Conway M. Type 2 inflammation modulates ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in airway epithelial cells [e-pub ahead of print]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.004 accessed June 27, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Matsuyama S., Kawase M., Nao N. The inhaled corticosteroid ciclesonide blocks coronavirus RNA replication by targeting viral NSP15. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.11.987016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]