Abstract

In his 20 years in power, Vladimir Putin has employed a savvy use of social policy to bolster his popularity, but it is a set of policies not well designed to address Russia's chronic under-provision of healthcare, education, and other social services—particularly in rural areas. The COVID-19 global pandemic will only exacerbate Russia's social policy challenges and could pose a threat to Putin's political survival.

This year is a challenging time for Vladimir Putin and the Russian government. A decade of stagnating living conditions, falling oil prices, on-going military conflicts in Syria and Ukraine, and the COVID-19 global pandemic pose unique challenges for Putin, who has been in power for more than 20 years. A popular referendum on proposed constitutional amendments, originally scheduled for April 22, has already been postponed as Russia, like many countries, focuses on addressing the global coronavirus pandemic.1

Putin and his current government's ability to weather these crises will determine whether he can remain in power and direct Russia's government. A significant part of the answer lies with how the Russian government handles social policy. Putin may or may not survive the current crises (he has survived many crises to date, suggesting he may do so again), but it is certain that Russia's struggling healthcare system and the urban-rural divide will mean that the COVID-19 pandemic will cause tremendous suffering.

Putin's social policies in the 2000s have followed a combination of market-oriented policies with strategically targeted benefits, a set of policies dubbed “Putinomics.”2 Much of the social policy decision-making has been elite-driven and characterized by competing bureaucratic proposals with limited public input.3 Benefits have been assured for certain groups, like pensioners at strategic times (right before elections), but there is a lack of long-term planning and accountability in delivering better services, particularly in rural areas.4

While, in principle, this persistent underperformance of basic government promises in healthcare, education, and other areas could threaten Putin's popularity, no serious political alternative exists for whom to vote or support. Perhaps, this situation could change with the current global pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic is seriously exacerbating long-standing deficiencies and challenges that the Russian government faces. The dual socioeconomic and fiscal challenges pose threats for the Putin administration, but there is little room for opposition to organize effectively and nor is there an alternate narrative that could lead to a political transition.5

The question, then, is when Russian citizens might be frustrated enough with failures in public policy provision for a real political transition to happen. It is a difficult question to answer. A lot rests on Russians’ expectations of what actually will be provided. As unsatisfying as it is to admit, we are not likely to know whether a social crisis will lead Putin to lose political power until it happens. In the meantime, however, social policy provision throughout the 2000s lends insight into Russia's current political situation and the country's response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Putin's Socioeconomic Strategy in the 2000s

Putin became popular in large part for ushering in an era of greater stability and growth in the early 2000s. When he first came to power, Putin was hailed as someone who might be able to address the problems of a weak state and rampant corruption from the 1990s. As part of this challenge, he reorganized the Russian bureaucracy and introduced reforms to some areas of social policy. Social policies in the areas of pensions, healthcare, education, family benefits, and unemployment support have been central to Putin's strategy for staying in power.

Vladimir Putin taking the Presidential Oath, May 7, 2000

By 2018, when Putin was elected to his fourth term as president, he was still making the same promises to improve social services as he did when he first ran in 2000. After this election, however, things changed. Shortly after his election in 2018, the Russian government announced and quickly pushed through an unpopular increase in the retirement age. Putin and the Russian government were taking advantage of his recent re-election—and the distraction of the World Cup in summer 2018—to implement a change that had long been hailed as necessary, but which Putin and United Russia had long promised would not happen.

In early 2020, at his annual address to the nation, Putin announced proposed major constitutional changes.6 Amidst these changes, the Russian press extensively reported on the social policy promises that were included. Putin proposed, for instance, including in the constitution provisions addressing the minimum pension and a minimum wage for workers. The inclusion of these particular measures was very intentional. The constitutional referendum was scheduled for April 22, but has been postponed—most likely until June at the earliest—due to concerns about the pandemic.7 Over the course of the 2000s, we can see the different ways that an authoritarian regime makes and uses social policies that critically affect the daily quality of life for their citizens. We can also envision how this system might be difficult to sustain amidst a pandemic crisis.

Building Popular Support: 2000-2009

Putin used social policy to build his base of popular support, but the bar for functioning social policy was quite low. He (somehow) managed to get regional governments to start fulfilling their obligations to pay pension benefits, which are already and the books and which they have not been paying out. This is no small accomplishment. The bigger issue is that the general economy does much better so that the burden to have better functioning social support immediately is (arguably) a little less critical.

There were some remarkably liberal and market-oriented policy reforms, including ones like pension privatization. Putin also managed to reform the tax system and improve tax collection. This was an enormous and very necessary achievement in the early 2000s. Healthcare was another policy area where major changes were adopted although their implementation is spotty. Russia adopted a mandatory universal health insurance model somewhat akin to the German system. Yet, the reformed system was not set up as intended in many regions of Russia. And even at present, the Russian healthcare system struggles to provide adequate care; elites often prefer to be treated abroad, domestic observers note.8 While some improvements were undertaken in areas like education too, many problems remained.

Most significantly, when general economic conditions improve, there is political stability. Employment and wages improved, Russians had access to credit and more consumer goods, and Russia, in general, seemed to be on the rise. Given the socioeconomic and political developments of the early 2000s, it is not hard to see why Putin was so popular. Many observers still emphasize the comparison of Russia in the 2000s with “the damned 90s” to explain why Putin is so popular.9 While this explanation is true, it is not the whole story given that by many metrics conditions have been stagnating since the financial crisis of 2009.

Stagnation: 2009-2020

The last decade has seen a financial crisis and recovery period. During this time, we have begun to see dissatisfaction and the possibility that the Russian public will not accept continued stagnation in areas like healthcare and education services—especially when general economic conditions are weak. There are some protests. Opposition candidates and parties look poised to do better. Ultimately, though, Putin and his government maintain power with skillful strategies from the authoritarian toolkit. The quality of social policies did not fare well.

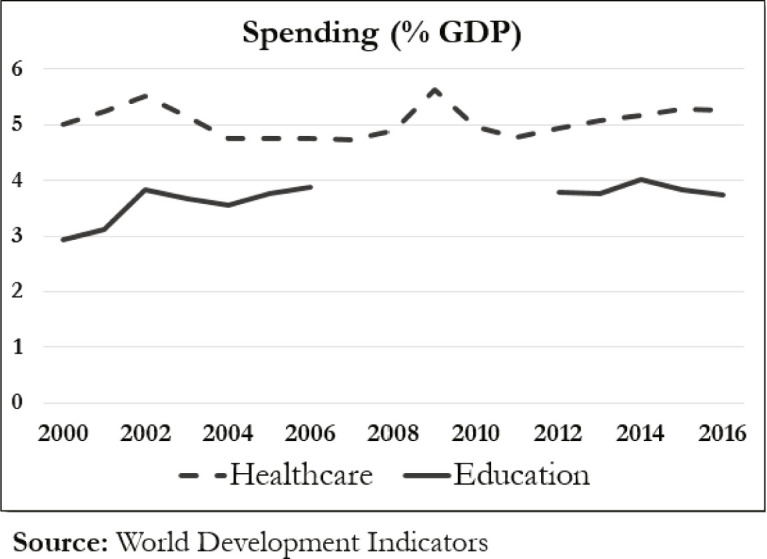

The improved conditions in the early 2000s levelled off, and we see significant stagnation in social spending and a lack of real improvement in the quality of education and healthcare. It was during this period that the Russian government reversed pension privatization. Russia's spending on healthcare and education as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) was already well below the European average and has not increased in the 2000s. Figure 1 (above) shows all education and healthcare spending data available from the World Bank at the time of writing. Throughout the 2000s, spending on healthcare as a percentage of GDP has hovered around five percent and spending on education has remained between three and four percent.

Figure 1.

Healthcare & Education Spending in Russia, 2000-2016.

Healthcare conditions have not improved in recent years.10 Although the official statistics are not good, even those probably gloss over major deficiencies. A recent report found that a third of medical facilities in Russia lack running water, 52 percent do not have hot water, and a shocking 40 percent are without central heating. Nearly half lack access for citizens who are disabled.11

In the run-up to Putin's 2018 presidential election, Vedomosti published a critical account of what Putin and United Russia had promised and their failure to deliver on many of those promises. They had promised a specific number of schools and more slots in kindergartens, but chronic shortages persisted.12 Since Putin's reelection in March 2018, the government implemented a widely unpopular measure to raise the retirement age, which current Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin has promised to keep in place. Through all of this, Putin's approval rating remains above 60 percent (with a high of nearly a 90 percent.)13

Crisis & Change in 2020

Russia in the modern period is an excellent example of how and why authoritarian regimes do care about public opinion and also why the nature of their political institutions do not produce better outcomes.

In the first three months of 2020, the entire Russian government, including the long-standing Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, resigned. This turmoil was followed by the proposal of major constitutional amendments, including proposals to allow Putin to run for a fifth term as president in 2024. Remarkably, these constitutional amendments include several specific promises regarding social policy benefits.

Much of the speculation about Putin's proposed constitutional amendments has focused on the institutional changes, which alter the role of the presidency, parliament, and Security Council. Most observers, including policy analysts and academics, have focused on what this means for Putin's future after 2024, when his current presidential term would officially end. Konstantin Sonin, University of Chicago professor, however, noted that speculating about what the constitutional amendment means for Putin and his strategy to stay in power is premature. While the current maneuvering could be the sign of Putin's strategy, Sonin and others have observed rightly that the current proposals for constitutional amendments leave a variety of options for what Putin could do.

Moreover, the importance of the other big issue mentioned in the proposed constitutional amendments—social policy spending, with a specific focus on pension policy—has received much less attention. Nonetheless, a few savvy observers have written that the social policy and welfare aspects of the proposed amendments may prove to be the most important. In a recent edition of the Russian Analytical Digest, several contributors noted the importance of social policy promises and rising dissatisfaction among Russian citizens.14 Regina Smyth, a professor at Indiana University, sums up the situation well:

In the longer term, these changes in the definition of state-society relations are potentially more significant than the formal amendments or the reinforcement of existing informal practices to maintain oligarchy. They are also risky. The regime's advertisement for improved quality of life will raise social expectations about state performance and the quality of services in the context of a geriatric system that has been in power for 20 years. If the government fails to meet expectations, the short-term project to insulate the ruler and his cronies is vulnerable to political unrest, and medium-term state development will be complicated.15

Other commentators agree, indicating that the Mishustin government will be expected to fulfill the social policy promises that Putin made in January 2020.16 Still, others write, however, that the replacement of other positions—like the minister of health—appear to be merely window dressing, lacking in any real substantive change.17 In any case, short-term goals related to improving the economy and the quality of life will determine whether other big institutional changes can happen.18 In a late 2019 poll, conducted by the Levada survey organization, 51 percent of respondents indicated that they want to live a better life (up for a response rate of 42 percent in 2007).19

Social policy and its relation to basic living standards are at the heart of current Russian politics, and the Kremlin is taking notice: the constitutional amendments proposed in early 2020 included several specific mentions of social policy, among them a remarkable promise to increase pensions and other social benefits annually.20

If Mishustin and his new government fail to improve conditions in keeping with these new constitutional promises, then many of our current questions about what happens in 2024 may be moot. And, at this point, who knows how long Mishustin will stay as prime minister. When Yeltsin was in the last year of his second term, he quickly cycled through prime ministers in rapid succession when financial crises and problems in Chechnya arose. Putin still has four years to try out different prime ministers who could play a variety of roles in a post-2024 system with a new constitution.

The Russian media has further emphasized these social policy promises, some with a more positive tone and others with a surprising amount of cynicism. One headline ridiculed the current promises saying, “Pensioners are waiting for gifts from Mishustin—2 pirozhkis [donuts] with jam” alongside a photo of dejected looking pensioners. Mishustin has denied emphatically that the government will go back on its 2018 decision to raise the retirement age. Nonetheless, there appears to be a strong expectation that the government should and will provide pension benefits and make some efforts to improve healthcare. It is worth noting that the Russian public is largely (though not entirely) aware of the proposed constitutional amendments, but it has expressed skepticism about what the new government can actually accomplish. Herein lies the current Russian government's challenge: the government must address current concerns, set realistic expectations, and (at least somewhat) follow through. But Russian governments in the 1990s and the later 2000s (especially from 2009 and beyond) have something important in common: 10 years of stagnating economic conditions make these promises both vital for political support and, potentially, less credible.

Citizens in authoritarian regimes lack regular, competitive elections in which to voice their discontent. This infrequency makes it difficult to predict where their breaking point is. In Russia today, expectations are low for government performance, especially in the area of social policy. There are no good alternatives to Putin and United Russia at present. The new government appointed in early 2020 may fail to get much done, and that may be acceptable to the Russian public. If anything improves in the arena of social policy and welfare, then it may be enough to keep a majority Russians happy. In other words, the promise of better things and just minimal follow through could be enough. Table 1

Table 1.

Constitutional Amendments Referencing Social Policy.

| Existing Text | Proposed Amendment | |

|---|---|---|

| Article 71 (revision of part “e”) | Establishing the basics of federal politics and federal programs in the area of the state, economics, ecology, social, cultural, and national development of the Russian Federation | Establishing the basics of federal politics and federal programs in the area of the state, economics, ecology, scientific-technical, social, cultural, and national development of the Russian Federation; establishing a singlelegal basis for systems of healthcare, and systems of upbringing and education, including continuing education. |

| Article 72 (revision of part “zh”) | Coordination on questions of healthcare; protection of the family, maternity, paternity and children, social protections including social provision | Coordination on questions of healthcare especially regarding the provision of sufficient and quality medical care, preserving and protecting public health, building the goal for the introduction of healthy quality of life, forming cultures of responsibility in relation to citizens and their health. |

| Article 75 (addition of parts 5, 6, and 7) | Not applicable; these portions are entirely new | 5. The Russian Federation respects the labor of citizens and provides for the protection of their rights. The state guarantees a minimum wage not less than a living wage for all of the population in the Russian Federation capable of working. 6. In the Russian Federation there is formed a system of pension provision for citizens with the basic principles of equity, justice, and solidarity in supporting its effective functioning, and also implementing the indexation of pensions no less than once a year as dictated by federal law. 7. In the Russian Federation in keeping with federal law, there is a guarantee of social insurance, social support of citizens and the indexation of social benefits and other social payments. |

Note: Translation from Russian into English by the author. For revised sections of Articles 71 and 72, the new text has been italicized. The new portions of Article 75 are entirely new sections.

There is significant speculation about what Putin's role in the government will be after 2024. In one scenario, he may find a way to stay in power, but in a different role. If this scenario happens, we might be less optimistic about seeing an improvement in Russia's social policy. The best hope for improving social policy would be to have competing groups of elites pitted against each other in a race to provide better, more credible promises and policies. At the moment, this scenario seems unlikely.

Pension policy is a prime example of how social policy in Russia is the domain of elites with limited public input. When the financial crisis hit in 2009, the Russian government quickly spent down the Stabilization Fund created from revenue from state-owned oil companies. The government needed funds quickly. This demand became even more intense after the Russian government invaded Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2013. As such, one means of gaining short-term funds was to suspend (or freeze) contributions to individual pension accounts and instead return this money into general government coffers. This is precisely the move that the Russian government made. After first freezing contributions (in principle temporarily) in 2012, the Russian government has yet to reopen contributions to the privatized accumulative portion of pensions. The 2001 reform has been killed effectively. Furthermore, the government made this move with virtually no public input.

Putin reversed his pension policy again when he chose to support the very unpopular measure of increasing the retirement age. In spring 2018, shortly after what is likely Putin's final election as president, then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev announced an increase in the Russian retirement age.21 By the summer, Putin announced that he did not like raising the retirement age, but it was necessary.22 Increasing the retirement age has long been considered by economists and policy analysts to be an economic and fiscal necessity in Russia, where the retirement age was relatively low (55 for women and 60 for men). In addition, the state struggled to support an aging and shrinking population. With the next Duma elections not until 2021 and presidential elections not until 2024, Putin and United Russia have plenty of time to recover from a public backlash. Furthermore, the announcement was made shortly before the World Cup, which was being hosted in Russia that summer to allow for maximum distraction.23 Despite some protests and objections, the legislation to increase the retirement age went through quickly in fall 2018.24 As in other areas of social policy, the Russian government cared about a public backlash, but not about true public input.

Pension politics provides an important lesson about Russia's authoritarian politics: the government cares about buying off enough of the population at the right times with short-term promises of benefits (like one-time payments right before elections). Yet, it is less concerned about long-term planning. Additionally, Russian political institutions currently do not create good incentives for long-term accountability for elected officials or political parties to produce better outcomes. As Robert Orttung, a professor at George Washington University, notes, institutions matter in Putin's Russia in that they regularly change, but Russian institutions “put few effective constraints on a top leader willing to shape the institutions to serve his personal interest rather than those of the country.”25

Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Russia

Russia, like most other countries around the world, is facing the unprecedented challenge of addressing the COVID-19 global pandemic. Russia's response to the pandemic can be understood in terms of its larger social policy and public policy strategies. The Russian response to the COVID-19 pandemic is also consistent with Putin's authoritarian strategies for staying in power. Marlene Laruelle, George Washington University professor, and Madeline McCann, program coordinator for PONARS Eurasia and George Washington University, argue that Russia's response is emblematic of a post-Soviet response to the pandemic in which political leaders understate the extent of the crisis and the potentially catastrophic consequences for public health.26

Schools and universities in Russian cities were closed down in March with a transition to online and remote learning seen in many countries around the world. Russia closed its borders to most foreign nationals until (at the earliest) May 1, 2020. In late March 2020, Putin announced a week-long “holiday” and a subsequent three weeks of quarantine measures. Muscovites, in particular, faced strict restrictions including a mandatory propusk (pass) system in which residents have been required to register for passes in order to leave their home. On May 22, Mayor Sobianin announced that many of these measures would continue including the propusk system. 27

Putin initially maintained that Russia has the situation under control, but other events suggested that the government was woefully underprepared in March of 2020. A spike in severe pneumonia cases in Moscow prompted concerns that the official COVID-19 infection numbers were vastly understated.28 The understating of numbers is an issue in many countries, and it is almost certainly the case in Russia, where only limited testing is taking place. Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin has indicated that the coronavirus is a major crisis and that the “stay at home” order will remain in place indefinitely. The Russian government has already started building a new hospital in the Moscow region.

But many regions of Russia are doing little to reduce the spread of coronavirus and are already incapable of providing healthcare for existing needs. Consistent with this, anecdotal evidence suggests that mid-size Russian cities like Ulyanovsk may end up being hot spots for the virus.29 This does not bode well for containing the virus’ spread. Furthermore, many Russians are skeptical about what the government can do. In a poll conducted in late March 2020, 48 percent of Russians responded “definitely not” or “for the most part no” in response to a question asking whether the healthcare system in Russia would be ready if a coronavirus epidemic started. Nearly a quarter of Russians answered that they did not trust the official information on the coronavirus situation in Russia being reported by the media.30 On April 10, 2020, Moscow Mayor Sobyanin announced that there was no choice but to institute a “propusk,” or pass system. Moscow residents will need to print or download to their phones passes for all excursions outside of their homes with the exception of visiting the closest grocery store to their home.31

In short, Russia faces a very serious crisis with the spread of coronavirus. Putin has acknowledged that the situation is getting worse, and Mayor Sobyanin has announced that Russia is nowhere near its peak of infections and deaths.32 The Russian government has grossly underfunded the country's healthcare infrastructure, resulting in a healthcare system that is underprepared to deal with this kind of pandemic crisis. Even countries with advanced, well-functioning healthcare systems are struggling to deal with the rapid spread of the virus.

What Does Russia's Social Policy Tell Us About Russian Politics?

Social policy is important on its own as one of the central functions of modern governments and among most governments’ largest areas of spending, a bellwether of other political changes, and an important part of the authoritarian toolkit. Social policy is also the most directly relevant aspect of Russian politics for many average citizens. We would do well to pay attention to the domestic promises made and received by the Russian government; it tells us a lot about how the country is working and where it is going. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, social policy is moved to the very forefront of politics.

This article has highlighted three periods of social policy under Putin: first, the early 2000s when rising oil prices helped promote rapid economic growth and Putin introduced a stability that was unknown in the 1990s; second, the financial crisis of 2009 and the subsequent stagnation that Russia has still not managed to overcome, and third what looks like—at least at present—the consolidation of authoritarianism and the possible creation of a new social contract (or at least promises to actually provide for the existing social contract).

The recently proposed constitutional amendments highlight the central importance of social policy support and pension policy to the Russian public. A great deal depends on what the Russian public is really expecting the government to do and whether the government does it. The former—what the public really wants and expects—is the crucial question that no one can currently answer. What is critical moving forward is to conduct more extensive survey work, making more clear the distinction between what Russian citizens want in principle and what Russian citizens actually expect the state to provide.

One of the most persistent Communist-era beliefs—among all generations—is that the state should provide a range of welfare benefits, including state-provided and state-guaranteed pensions.33 The beliefs are pervasive, strong, and related to the Communist-era systems, which were not overly generous, but were universal and allowed for a guaranteed basic level of services. But what do citizens of post-Communist states think the state will actually provide? This is the key outstanding question.

Russians display a remarkable amount of cynicism about their own social services and for very good reasons. If the government can exceed very low expectations, then this may be enough to allow for regime stability. But Russians have faced more than a decade of stagnation raising the very real question of how much longer the leadership can get away with failing to improve living conditions for millions of Russians. Ultimately, whether President Putin, Prime Minister Mishustin, and United Russia can convince Russians that they are improving (or can improve) their lives will determine the future of Russia.

Footnotes

“Kremlin announce a new date for voting on the Constitution,” [“Kreml’ zaiavil ob otsutsvii novi dati golosovaniia po Konstitutsii,”], RBK, April 6, 2020.

Chris Miller, Putinomics: Power and Money in Resurgent Russia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

Andrea Chandler, Shocking Mother Russia: Democratization, Social Rights, and Pension Reform in Russia, 1990-2001 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004); Linda Cook, Postcommunist Welfare States: Reform Politics in Russia and Eastern Europe (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2007); Thomas Remington, “Institutional Change in Authoritarian Regimes: Pension Reform in Russia and China,” Problems of Post-Communism, vol. 66, no. 5, 2019; and Sarah Wilson Sokhey, The Political Economy of Pension Policy Reversal in Post-Communist Countries (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Sarah Wilson Sokhey, “Buying Support? Putin's Popularity and the Russian Welfare State,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, Feb. 2018.

Ksenia Kirillova, “Prospectis of the Russian protest movement,” Atlantic Council, Oct. 28, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/prospects-of-the-russian-protest-movement.

Andrew Higgins, “Russian Premier Abruptly Quits Amid Swirl of Speculation on Putin,” New York Times, Jan. 15, 2020.

Elena Mukhametshina, “Voting on the amendments to the Constitutions may be rescheduled in June,” [“Golosovanie po popravkam v Konstitutsiiu mozhet byt’ pereneseno na iiun’], Vedomosti, March 22, 2020.

V. V. Moissev, “Healthcare Problems in Modern Russia,” Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, vol. 128, 2020.

Anders Åslund, Russia's Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

Jake Cordell and Evan Gershkovich, “‘We Don’t Have Enough Intensive Care Beds’: Coronavirus Will Test Russia's Creaking Healthcare System,” Moscow Times, March 19, 2020.

“1 in 3 Russian Hospitals Lack Water Supply—Audit Chamber,” Moscow Times, Feb. 7, 2020.

Andrei Illarionov, “10 unfulfilled promises of Putin and Medvedev,” [“10 nepolnennykh obeschanii Putina i Medvedeva”], Vedomosti, May 5, 2017.

Work by Frye et al. suggests that these approval ratings are likely only inflated by about 10 percentage points.

See, “Putin's Power Games,” Russian Analytical Digest, no. 246, Feb. 7, 2020.

Regina Smyth, “The Reality of Russia's Constitutional Reform: Limited Institutional Change Masks a Profound Shift in Economic Policy,” Russian Analytical Digest, no. 246, Feb. 7, 2020.

Maria Domańska, “Putin's January Games: ‘Succession of Power’ on the Horizon,” Russian Analytical Digest, no. 246, Feb. 7, 2020.

Vladimir Gel’man, “The New Russian Government and Old Russian Problems,” Russian Analytical Digest, no. 246, Feb. 7, 2020.

Michael Rochlitz, “Putin's Plan 2.0? What Might Stand Behind Russia's Constitutional Reform,” Russian Analytical Digest, no. 246, Feb. 7, 2020.

“More Russians want to live better,” [“Rossiiane bol'she zahoteli zhit’ luchshe”], Kommersant, Jan. 17, 2020.

“Full text of the amendments to the Constitution: What are we voting for?” [“Polnyi tekst popravok v Konstitutsiiu: za shto my golosuem?], http://duma.gov.ru/news/48045/.

Georgii Yashunskii, “Medvedev announces the development of legislation on changing the retirement age,” [“Medvedev anonsiroval razrabotku zakonoproekta ob izmenenii pensionnogo vozrasta”], Vedomosti, April 28, 2018.

“Putin doesn’t like raising the retirement age,” [“Putinu ne nravitsia povyshenie pensionnogo vozrasta,] TASS, July 20, 2018.

Pavel Felgenhauer, “Will Soccer Carnival Cover up Russia's Highly Unpopular Pension Reform?” Eurasia Daily Monitor, vol. 15, no. 96, 2018.

“Surprise from Putin: Protests against pension reform in the regions,” [“Supriz ot Putina. Protesty protiv pensinnoi reform v regionakh], Radio Freedom, [Radio Sboboda], June 4, 2018; and “Ratings of United Russia fell to a ten-year low,” [“Reiting ‘Edinoi Rossii’ upal do desyatiletnego minimuma], Aug. 3, 2018.

Robert Orttung, “Do Institutions Matter in Putin's Russia?” Russian Analytical Digest, Feb. 7, 2020.

Marlene LaRuelle and Madeline McCann, “Post-Soviet State Responses to COVID-19,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo no. 671, March 2020, http://www.ponarseurasia.org/memo/post-soviet-state-responses-covid-19-making-or-breaking-authoritarianism.

Daria Korzhova and Svetlana Bocharova, “Sobianin zaiavil o neobhodimosti prodlit’ rezhim samoizoliatsii v Moskve,” [“Sobianin announced the necessity of continuing the regime of self-isolation in Moscow”], Vedomosti, May 22, 2020.

“Russia to Diagnose Coronavirus Without Tests as Suspicions Mount,” Moscow Times, April 10, 2020.

Mikhail Bely, “‘A City that Could Be the Russian Bergamo’: How Ulyanovsk is Preparing for the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Moscow Times, April 3, 2020.

“The Coronavirus Situation in Russia,” Levada survey organization, April 13, 2020, https://www.levada.ru/en/2020/04/13/the-coronavirus-situation-in-russia.

“Coronavirus. Additional measures for the work of the city's organization and other decisions. 10.04.2020,” [“Koronavirus. Dopolnitel’nye organicheniia na rabotu gorodskikh organizatsii i drugie resheniia 10.04.2020], see Sergey Sobyanin website, https://www.sobyanin.ru/koronavirus-dopolnitelnye-ogranicheniya-i-drugie-resheniya-100420 .

“Russia's Coronavirus Outbreak is ‘Changing for the Worse,’ Putin Warns,” Moscow Times, April 13, 2020.

Grigore Pop-Eleches and Joshua Tucker, Communism's Shadow: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Political Attitudes (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017)